Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine the potential moderating effect of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on the emotion-behavior relationship in individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN).

Method

A total of 119 women with BN were involved in the study. Participants were divided into two groups: those with BN and PTSD (n = 20), and those with BN only (n = 99). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) procedures were utilized for the examination of affect, frequency of bulimic behaviors, and the relationship of affect and bulimic behavior over time. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders was conducted for the diagnosis of BN, PTSD, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders functioned as covariates in all analyses.

Results

Statistical models showed that those in the PTSD group reported a greater daily mean level of negative affect and a greater daily frequency of bulimic behaviors than those in the BN only group. Moderation was found for the association between negative affect and time in that the PTSD group showed a faster acceleration in negative affect prior to purging and faster deceleration in negative affect following purging. The association between positive affect and time was also moderated by group, indicating that the PTSD group had a faster acceleration in positive affect after purging than the BN only group.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance of recognizing PTSD when interpreting the emotion-behavior relationship in individuals with BN.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, Bulimia nervosa, Palm top computers

1. Background

1.1 Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and bulimia nervosa (BN)

Individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) are five times more likely to report posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than those without BN [1]. Despite the increased prevalence of PTSD among individuals with BN, little is known about the relationship of PTSD and BN. Some studies have shown that women with PTSD do not exhibit differing severity levels of disordered eating behaviors than those without PTSD [2,3]. Other studies suggest that PTSD appears to mediate the association between trauma and disordered eating behaviors [1,4]. That is, although individuals with PTSD may not report a greater frequency of eating disorder symptoms compared to those without PTSD, experiencing PTSD may be a crucial piece of the puzzle for examining and treating individuals with BN who have experienced trauma. Indeed, some researchers theorize that emotion dysregulation is a key component bridging PTSD and BN [1,4,5].

1.2 Emotional responding in PTSD and BN

Problems with emotional responding and emotion regulation associated with PTSD may result after a traumatic event, and in turn, increase the risk for the development of BN [4,5,6,7]. To cope with the heightened emotional sequelae of victimization, an individual may engage in disordered eating behaviors, in order to avoid cognitively re-experiencing the traumatic event and to alleviate the hyperarousal and associated emotional distress [1,8]. Additionally, emotion dysregulation is a significant clinical phenomenon that characterizes both eating disorders and PTSD [5].

Currently little is known about differences in emotional responding between individuals with simple BN versus individuals with BN and comorbid PTSD. Examination of the relationship of bulimic behavior to emotions in individuals with and without PTSD may help clarify the function of the eating disorder behavior in these two groups of patients. The present study adds to current literature through the use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to measure BN behaviors and emotion variables in real time within the natural environment. Previous EMA studies have examined the occurrence of BN behaviors in relation to types of abuse [9], stress [10], anger [11], and nonsuicidal self-injury [12], but to date, none have explicitly examined the relationships among PTSD, emotional states, and BN behaviors.

The primary aim of the present study was to examine the potential moderating effect of PTSD on the affect-behavior relationship in individuals with BN. Three specific research questions were investigated:

Do BN participants with and without a diagnosis of PTSD differ in regard to level of affect and variability of affect? We hypothesized that participants with BN and PTSD would report more negative affect, less positive affect, and more variability in affect than those with BN only.

Do participants with and without a diagnosis of PTSD differ in regard to the daily aggregated frequency of bulimic behavior? Participants with BN and PTSD were expected to report a greater frequency of bulimic behaviors than those with BN only.

Do participants with and without a diagnosis of PTSD differ in regard to the relationship of affect and bulimic behavior over time? We also predicted that participants with PTSD and BN would show a stronger association between negative affect and bulimic behaviors both prior to and following binge eating and purging episodes than those with BN only. Additionally, participants with PTSD and BN were hypothesized to report a weaker association between positive affect and bulimic behaviors both before and after binge eating and purging episodes than those with BN only.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

The sample of participants included 119 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BN. Most participants were single, or never married (86%), Caucasian (97%), and had at least some college experience (60%). All women were at least 18 years of age (M = 24.98, SD = 7.42, range 18–55). The mean BMI for the sample was 24.01 (SD = 5.40). Participant recruitment involved advertisements in eating disorder clinics, college campuses, and the general community. Participants met the following inclusion criteria: a DSM-IV diagnosis of BN and medical and psychiatric stability for a minimum of 6 weeks. Pregnant women, men, and individuals below 18 years of age were excluded from the study. Based on PTSD screening, which will be described below, 20 participants were identified as having current diagnoses of both BN and PTSD (i.e., BN+PTSD); 99 participants were noted as having a diagnosis of BN only.

2.2 Assessment

Two assessment procedures were utilized for the present study: diagnostic interviews and ecological momentary assessments. Participants completed a series of semi-structured diagnostic interviews and provided responses to questionnaire assessments in a two-week EMA protocol.

2.2.1 Clinical interview

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition [SCID-I/P; 13] is strongly endorsed as a psychometrically valuable instrument. Structured clinical interviews were conducted for the assessment of BN, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and other comorbid psychopathological conditions. Doctoral level psychologists administered the SCID-I/P to all participants, and all participants met full DSM-IV criteria for BN. Participants were categorized into two groups: those who met current DSM-IV criteria for PTSD in addition to BN (i.e., BN+PTSD; n = 20) and those with BN only (n = 99). Cohen’s kappa (K) reliability coefficients based on a randomly selected subsample of participants (n = 25) were 1.00 for BN diagnoses and 1.00 for current PTSD diagnoses.

2.2.2 Ecological momentary assessment

Specific items were selected from a shortened version of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale [PANAS; 14]; items were chosen based on their factor loadings. Thirteen items were selected for positive affect [PA]: alert, attentive, calm, cheerful, concentrating, confident, determined, energetic, enthusiastic, happy, proud, strong, and relaxed. Eleven items were chosen for negative affect [NA]: afraid, angry with self, ashamed, disgusted, dissatisfied with self, distressed, irritable, jittery, lonely, nervous, and sad. Scores for PA ranged from 13 to 65, and scores for NA ranged from 11 to 55; higher scores indicated a greater level of affect. The PANAS has shown good internal consistency for both affective states [NA: r = .85; PA: r = .87; 14]. Cronbach’s alpha values for the current study were 0.91 for PA and 0.92 for NA.

Key items from the Eating Disorder and Self-Destructive Behavior Checklist were selected for the creation of a 19-item checklist [15,16]. This checklist was used for the assessment of momentary bulimic behaviors (e.g., “I binge ate”, “I vomited”, “I used laxatives”).

2.3 Procedure

Institutional Review Boards approved the protocol. Phone screenings were conducted to determine if participants met preliminary DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BN. A total of 154 individuals were invited to attend an informational meeting to learn about the study. During this meeting, potential participants completed the informed consent documents and provided blood samples for the determination of medical stability. Two additional meetings, which lasted four hours, were scheduled for participants to complete structured clinical interviews with doctoral level research staff. Based on the exclusion criteria, 11 individuals were screened out of the study, leaving a sample of 143 participants.

Following the first assessment meeting, participants were trained to use the palmtop computers for the EMA assessments. Research staff explained the goals of the study and the EMA data collection process. Participants were instructed to complete assessments of affect and to report occurrences of binge eating and purging behaviors on the palmtop computers. All participants were trained on how to define binge eating and purging events. Binge eating was defined as eating “an amount of food that you consider excessive or an amount of food that other people would consider excessive, with an associated loss of control or the feeling of being driven or compelled to keep eating.” Purging behaviors were defined as behaviors emitted in an effort to counteract eating episodes. These definitions were further discussed relative to participants’ eating habits reported during the initial interview process. After the first meeting participants completed two days of practice assessments, which provided data to be reviewed during the second assessment meeting (these data were not used within analyses). EMA data collection then took place over the following two weeks. To reduce potential losses of data and to assess participant compliance, 3–4 meetings with project staff were scheduled during the data collection period. Over the course of data collection, 7 participants withdrew from the study and 3 participants were removed due to incomplete data. Also, participants who had a lifetime history of PTSD, but not a current PTSD diagnosis (N = 14), were not included in order to provide a clearer examination of the effect of PTSD on momentary variables. Thus, the final participant sample included 119 women. Participants were compensated with $100 for each week of data collection and a $50 bonus for a minimum rate of 85% compliance with signaled prompts on the handheld computer within 45 minutes.

Three types of participant responses were incorporated in the EMA data collection period: signal contingent, event contingent, and interval contingent [17]. Signal contingent recordings were based on a personal digital assistant (PDA) - generated signal which occurred at six semi-random times each day, during the two-week interval. When signaled, participants were prompted to use the PDA computers to record their affect and BN symptoms. The semi-random signals occurred across six time blocks starting at 8:00am and ending by 10:00pm. Event contingent recordings required participants to report predetermined behaviors (i.e., binge eating, vomiting, laxative use) immediately after the event occurred. With this method of recording participants provided information about the occurrence of discrete events in real time. Interval contingent recordings were also included in the protocol as end-of-day records, thus allowing an anticipated recording session for participants to review their daily experiences. These ratings allowed an assessment of both behavior and affect since the last signal of the day.

3. Statistical Analyses

3.1 Research Question #1

Multi-level models were conducted to assess group differences (i.e., BN+PTSD, BN only) in the daily level and variability of affect (i.e., NA, PA). These models were based on a general linear model to examine the first research question. Data were aggregated across repeated assessments within days so that mean negative and positive affect scores could be calculated for each participant for each day of data collection. Variability in NA and PA was calculated with mean squared successive difference (MSSD) statistics to determine the average degree of variability in affect over time. MSSD values symbolized the variation in NA and PA each day in relation to the squared difference across successive time points and the distance between the measured time points [18]. Mixed model analyses were used to analyze levels of daily affect and variability in affect (Level 1) nested within subjects (Level 2). The mixed models included a random effect for subjects and fixed effects for group (BN+PTSD, BN only), mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD). Pseudo-R-squared values were calculated by comparing the residual values for the full versus null models.

3.2 Research Question #2

Generalized linear models were conducted to evaluate group differences (BN+PTSD, BN only) in the aggregated frequency of eating disordered behaviors across days (i.e., binge eating, purging). Because behavioral observations provided non-independent data, generalized estimating equations were used to compare the number of daily eating disordered behaviors (Level 1) nested within individuals (Level 2) based upon a Poisson model appropriate for count data. The models included a random effect for subjects and fixed effects for group (BN+PTSD vs. BN only). Mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD) were included as covariates. Pseudo-R-squared values were calculated by comparing the log-likelihood values for the full versus null models.

3.3 Research Question #3

Group classification (BN+PTSD, BN only) was investigated as a moderator for the assessment of the affect-behavior relationship preceding and following binge eating and purging events (i.e., BN-events). Trajectories of affect preceding and following the BN-event were modeled using piecewise linear, quadratic, and cubic functions centered on the BN-event time. The dependent variables for these mixed effects models were NA and PA. A variable was created representing time in hours prior to or following a binge eating or purging event with zero marking when the event took place. Mixed models included a random effect for subject, and fixed effects for group (BN+PTSD, BN only), mood disorders, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD), time in relation to the event (i.e., linear component), time-squared (i.e., quadratic component), time-cubed (i.e., cubic component), group-by-time, group-by-time-squared, and group-by-time cubed. Post-behavior trajectories were modeled by including interactions between pre/post (0 = pre-behavior; 1 = post-behavior) and all those effects listed above: group-by-pre/post; time-by-pre/post; time-squared by pre/post; time-cubed-by-pre/post; group-by-time-pre/post; group-by-time-squared-by-pre/post; group-by-time-cubed-by-pre/post. Models were analyzed to determine whether the regression lines for the PTSD group differed from the regression lines for the BN only group in terms of intercept, as well as the pre- or post-behavior linear time component (slope), quadratic time component (curve), and cubic time component (change in curvature). On days in which multiple BN-events were reported, only the first event was used due to the possibility of confounding effects for affect in association with the occurrence of additional BN-events. Pseudo-R-squared values were calculated by comparing the residual values for the full versus null models.

4. Results

4.1 Preliminary Analyses

The sample for this study included 119 participants who provided 11,687 separate EMA recordings representing 1,750 separate participant days. Recordings included 9,227 responses to signals, 1,006 reports of behaviors, and 1,454 end-of-day recordings. Participants reported an average of 8.01 binge eating episodes (SD = 6.76) and 11.45 purging episodes (SD = 9.95). Participants reported an average of at least one binge eating episode on 38% of the days and at least one purging episode on 49% of the days; both binge eating and purging episodes occurred as multiple events on 33% of the days.

Initial analyses were conducted to examine differences between the BN only and BN+PTSD groups on demographic and clinical characteristics. The BN+PTSD group was older than the BN only group (BN+PTSD: M = 28.85 years, SD = 8.14; BN only: M = 24.18 years, SD = 7.05; t117 = 2.63, p = .010). The groups did not differ in education level (X21 = 0.03, p = .862); however, the BN+PTSD group was more likely to be married than the BN only group (BN+PTSD; married: n = 7, 35.0%, BN only; married: n = 9, 9.3%, X21 = 9.29, p = .007). Group differences were not found for body mass index (BN+PTSD; M = 25.40, SD = 5.33, BN only; M = 23.73, SD = 5.40, t117 = 1.27, p = .208). Current comorbid psychopathologies were also prevalent across the BN+PTSD and BN only groups: mood disorders (BN+PTSD: 70.0%, BN only: 51.5%, X21 = 2.28, p = .131), substance use disorders (BN+PTSD: 15.0%, BN only: 16.5%, X21 = 0.03, p = .869), and other anxiety disorders (BN+PTSD: 70.0%, BN only: 40.2%, X24 = 13.37, p = .01). To directly assess the relationships between variables, these three comorbid conditions were used as covariates within all further analyses [19].

4.2 Research Question #1

4.2.1 Negative affect

Covariates for these analyses included mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders. After controlling for covariates, the BN+PTSD group reported a greater mean daily level of NA (M = 29.26, SE = 1.68) than the BN only group (M = 25.82, SE = 1.31; see Table 1). Significant group differences were not found for MSSD (F1, 370.48 = 0.03, p = .861). Covariance analyses also revealed no significant differences for anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD; F4,219.42 = 5.39, p = .793), mood disorders (F1,218.92 = 3.15, p = .078), and substance use disorders (F1,220.57 = 0.26, p = .610). The overall model accounted for 15.2% of the variance in NA (pseudo- R2 for the overall model = 0.152; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Between-Day Multilevel Models for Mean Level of Affect - Aggregated by Day

| DV | Effect | Estimate | (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affect | Group | 3.437 | 1.360 | .012* |

| Mood Disorders | −1.769 | 0.998 | .078 | |

| Substance Use Disorders | −0.696 | 1.364 | .610 | |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | −1.406 | 5.349 | .793 | |

| Positive Affect | Group | −0.244 | 1.459 | .867 |

| Mood Disorders | 5.699 | 1.069 | <.001*** | |

| Substance Use Disorders | −2.005 | 1.462 | .171 | |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | 1.653 | 6.265 | .619 |

Note. These analyses are based on 119 individuals. Group = BN+PTSD, BN only.

p < .05, two-tailed.

p < .01, two-tailed.

p < .001, two-tailed.

4.2.2 Positive affect

After controlling for covariates, group differences (i.e., BN+PTSD, BN only) were not found for mean daily levels of PA (F1, 218.76 = 0.03, p = .867) or MSSD across groups (F1, 369.80 = 0.20, p = .657). Covariance analyses revealed that mood disorders were associated with level of PA (F1,222.61 = 28.41, p < .001); however, substance use disorders (F1,224.00 = 1.88, p = .171) and anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD; F4,222.99 = 0.66, p = .619) were not significantly related to level of PA.

4.3 Research Question #2

4.3.1 Binge eating

Beyond the influence of the covariates, individuals with BN+PTSD reported a greater frequency of binge eating events per day (M = .74, SE = .07) than those with BN only (M = .59, SE = .04). Covariance analyses revealed that mood disorders (Wald X21 = 6.82, p = .009) and anxiety disorders (excluding PTSD; Wald X24 = 49.78, p < .001) were also positively associated with binge eating; however, substance use disorders were not significantly related to the frequency of binge eating (Wald X21 = 0.67, p = .413). The overall model accounted for 13.7% of the variance in binge eating (pseudo- R2 for the overall model = 0.137, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Between-Day Multilevel Models for the Frequency of Behavior - Aggregated by Day

| DV | Effect | Estimate | (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge Eating Events | Group | 0.226 | 0.086 | .009** |

| Mood Disorders | −0.184 | 0.071 | .009** | |

| Substance Use Disorders | 0.077 | 0.094 | .413 | |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | −0.974 | 0.281 | .001*** | |

| Purging Events | Group | 0.435 | 0.068 | <.001*** |

| Mood Disorders | −0.119 | 0.059 | .043* | |

| Substance Use Disorders | 0.068 | 0.077 | .376 | |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | 0.909 | 0.370 | <.001*** |

Note. These analyses are based on 119 individuals. Group = BN+PTSD, BN only.

p < .05, two-tailed.

p < .01, two-tailed.

p < .001, two-tailed.

4.3.2 Purging

Analyses of differences in purging behaviors showed that individuals with BN+PTSD reported a greater frequency of purging events per day (M = 1.07, SE = .10) than those with BN only (M = 0.70, SE = .06). Additional covariance analyses revealed that mood disorders (Wald X21 = 4.11, p = .043), and anxiety disorders were also associated with purging events (Wald X24 = 62.41, p < .001), whereas substance use disorders were not related to the frequency of purging behaviors (Wald X21 = 0.78, p = .376). The overall model accounted for 15.3% of the variance in purging (pseudo- R2 for the overall model = 0.153, see Table 2).

4.4 Research Question #3

4.4.1 Binge eating

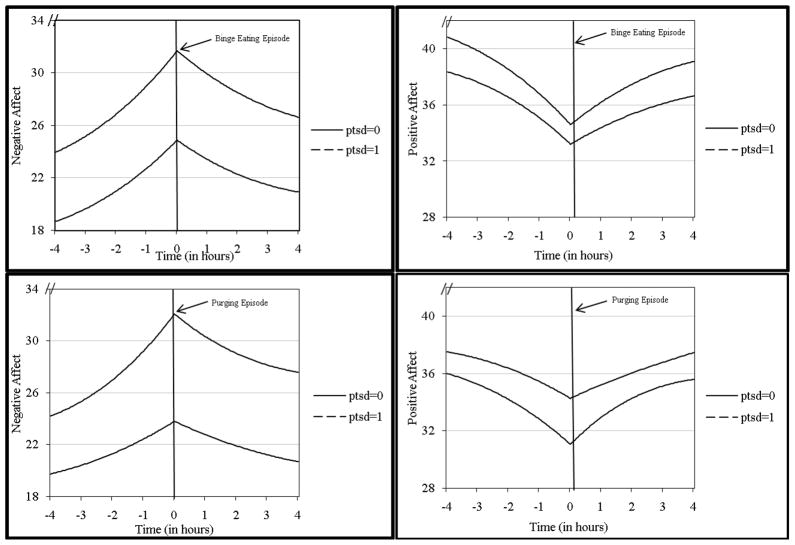

For both groups, NA significantly increased prior to binge eating and significantly decreased following binge eating (see linear, quadratic, and cubic estimates in Table 3). The intercept reported in Table 3 reflects the estimated value of the dependent variable at the time of binge eating for the BN only group; the estimate for the group effect reflects the difference between the BN+PTSD and BN only groups at the time of binge eating. This effect was significant, indicating a higher level of NA at the time of binge eating for the BN+PTSD group. However, the absence of any group-by-time interactions suggests that the pattern of NA around binge eating did not differ by group. These findings for the overall model were maintained after controlling for the effects of the covariates including mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders (pseudo- R2 for the overall model = 0.031; see Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 3.

Within-Day Multilevel Models for Binge Eating Events

| Negative Affect | Positive Affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | (SE) | df | t | Estimate | (SE) | df | t |

| Intercept | 24.88 | 1.297 | 89.984 | 19.189 | 33.207 | 1.126 | 116.938 | 29.498*** |

| Hours | 2.380 | 0.149 | 4137.670 | 15.938*** | −2.085 | 0.153 | 4194.415 | −13.634*** |

| (Hours)2 | 0.232 | 0.022 | 4137.546 | 10.553*** | −0.223 | 0.022 | 4194.343 | −9.904*** |

| (Hours)3 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 4137.313 | 7.125*** | −0.006 | 0.001 | 4193.873 | −6.970*** |

| Group | 6.796 | 2.307 | 101.081 | 2.946** | 1.391 | 2.028 | 119.949 | 0.686 |

| Hours* Group | 0.556 | 0.353 | 4137.967 | 1.601 | −0.337 | 0.362 | 4194.070 | −0.931 |

| (Hours)2* Group | 0.053 | 0.053 | 4138.071 | 1.016 | −0.021 | 0.054 | 4195.222 | −0.388 |

| (Hours)3* Group | 0.002 | 0.002 | 4138.408 | 0.885 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 4195.900 | −0.514 |

| Hours by pre-post | −4.024 | 0.272 | 4139.714 | −14.810*** | 3.406 | 0.278 | 4198.722 | 12.240*** |

| (Hours by pre-post)2 | −0.052 | 0.034 | 4138.190 | −1.537 | 0.092 | 0.035 | 4196.017 | 2.676** |

| (Hours by pre-post)3 | −0.011 | 0.002 | 4140.395 | −7.271*** | 0.010 | 0.002 | 4199.170 | 6.227*** |

| Hours* Group* Hours by pre-post | −0.866 | 0.634 | 4142.202 | −1.366 | 0.810 | 0.649 | 4195.957 | 1.248 |

| (Hours)2* Group* Hours by pre-post | −0.050 | 0.077 | 4138.204 | −0.651 | −0.031 | 0.079 | 4194.711 | −0.393 |

| (Hours)3* Group* Hours by pre-post | −0.001 | 0.003 | 4141.170 | −0.274 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 4194.391 | 0.351 |

| Mood Disorders | 2.001 | 1.674 | 86.416 | 1.195 | −7.072 | 1.443 | 109.428 | −4.903*** |

| Substance Use Disorders | 0.656 | 2.270 | 81.600 | 0.289 | 3.680 | 1.924 | 109.051 | 1.913 |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | 1.171 | 0.928 | 90.818 | 1.262 | 0.147 | 0.806 | 108.331 | 0.182 |

| Variance Terms | ||||||||

| Intercept Variance | 69.600 | 12.536 | 51.399 | 7.221 | ||||

| Autocorrelation Estimate | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.908 | 0.001 | ||||

| Autocorrelation Variance | 1.832 | 0.001 | 9.050 | 0.001 | ||||

| Residual Variance | 43.920 | 0.966 | 46.092 | 1.007 | ||||

Note. These analyses are based on 119 individuals. Group = BN+PTSD, BN only.

p < .05, two-tailed.

p < .01, two-tailed.

p < .001, two-tailed.

Figure 1.

Affect relative to bulimic behavior. Points represent predicted affect relative to time in hours.

Similarly, PA significantly decreased prior to binge eating, and significantly increased following binge eating for all participants (see linear, quadratic, and cubic estimates in Table 3). None of the main effects or interactions involving group were significant. Group did not moderate the relationship between PA and time of binge eating (see Table 3, Figure 1).

4.4.2 Purging

For both groups, NA significantly increased prior to the purging event, and significantly decreased following the purging event (see linear, quadratic, and cubic estimates in Table 4). The intercept reported in Table 4 reflects the estimated value of the dependent variable at the time of purging for the BN only group; the estimate for the group effect reflects the difference between the BN+PTSD and BN only groups at the time of purging. Like binge eating, the group effect was significant, indicating a higher level of NA at the time of purging for the BN+PTSD group. Group also significantly moderated the association between NA and time, indicating that in comparison to the BN only group, participants in the BN+PTSD group reported a faster acceleration in NA prior to the purging event and a faster deceleration in NA after the purging event. In other words, the temporal relationship between NA and purging differed between groups. After controlling for the effects of the covariates, these findings for the overall model were maintained (pseudo- R2 for the overall model = 0.050; see Table 4, Figure 1).

Table 4.

Within-Day Multilevel Models for Purging Events

| Negative Affect | Positive Affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | (SE) | df | t | Estimate | (SE) | df | t |

| Intercept | 23.814 | 0.956 | 214.790 | 24.917*** | 34.265 | 1.177 | 93.139 | 29.122*** |

| Hours | 1.509 | 0.136 | 4824.051 | 11.122*** | −1.319 | 0.145 | 4908.858 | −9.118*** |

| (Hours)2 | 0.135 | 0.020 | 4824.358 | 6.616*** | −0.142 | 0.022 | 4909.110 | −6.529*** |

| (Hours)3 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 4824.919 | 3.841*** | −0.004 | 0.001 | 4909.521 | −4.426*** |

| Group | 8.267 | 1.749 | 252.025 | 4.727*** | −3.206 | 2.165 | 103.067 | −1.481 |

| Hours* Group | 1.680 | 0.345 | 4826.029 | 4.863*** | −0.623 | 0.368 | 4910.336 | −1.692 |

| (Hours)2* Group | 0.207 | 0.054 | 4826.317 | 3.827*** | −0.054 | 0.058 | 4910.604 | −0.938 |

| (Hours)3* Group | 0.006 | 0.002 | 4826.176 | 3.060** | −0.001 | 0.002 | 4910.522 | −0.639 |

| Hours by pre-post | −2.643 | 0.239 | 4826.957 | −11.067*** | 2.352 | 0.255 | 4911.089 | 9.237*** |

| (Hours by pre-post)2 | −0.039 | 0.029 | 4826.707 | −1.342 | 0.058 | 0.031 | 4910.905 | 1.899 |

| (Hours by pre-post)3 | −0.005 | 0.001 | 4827.032 | −4.164*** | 0.006 | 0.001 | 4911.022 | 4.285*** |

| Hours* Group* Hours by pre-post | −2.520 | 0.591 | 4827.788 | −4.260*** | 1.763 | 0.631 | 4911.478 | 2.796** |

| (Hours)2* Group* Hours by pre-post | −0.058 | 0.075 | 4825.028 | −0.770 | −0.168 | 0.080 | 4909.522 | −2.087** |

| (Hours)3* Group* Hours by pre-post | −0.012 | 0.003 | 4827.260 | −3.623*** | 0.010 | 0.004 | 4911.271 | 2.711** |

| Mood Disorders | 1.862 | 1.226 | 212.187 | 1.519 | −7.179 | 1.512 | 91.534 | −4.723*** |

| Substance Use Disorders | −0.590 | 1.714 | 205.390 | −0.344 | 4.403 | 2.119 | 89.420 | 2.078** |

| Other Anxiety Disorders | 1.182 | 0.693 | 212.521 | 1.704 | −0.166 | 0.858 | 91.466 | −0.193 |

| Variance Terms | ||||||||

| Intercept Variance | 36.945 | 4.608 | 56.620 | 9.784 | ||||

| Autocorrelation Estimate | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | ||||

| Autocorrelation Variance | 2.105 | 9.072 | 1.358 | 0.001 | ||||

| Residual Variance | 43.022 | 0.876 | 48.897 | 0.987 | ||||

Note. These analyses are based on 119 individuals. Group = BN+PTSD, BN only.

p < .05, two-tailed.

p < .01, two-tailed.

p < .001, two-tailed.

PA significantly decreased prior to the purging event, and significantly increased following the purging event (see linear, quadratic, and cubic estimates in Table 4). Although the overall group effect was not significant, group moderated the association between PA and time following the purging event. Compared to participants in the BN only group, those in the BN+PTSD group reported a faster acceleration in PA after the purging event (see Table 4, RFigure 1). That is, the temporal relationship between PA and purging differed between groups. These findings for the overall model were maintained after controlling for the effects of the covariates including mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders (pseudo- 2 for the overall model = 0.057; see Table 4, Figure 1).

5. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the potential moderating effect of PTSD on emotions and behaviors in individuals with BN. Like previous research involving trauma and BN, comorbid conditions including mood disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders were prevalent across participants [20,21]. Yet, after controlling for these comorbid psychopathologies, findings from the study reflected fundamental differences in emotional responding and emotion regulation for individuals with BN and PTSD (i.e., BN+PTSD) versus those with BN only.

5.1 Research Question #1

In line with the first research question, individuals with BN+PTSD reported a greater mean daily level of NA than those with BN only. This is similar to previous studies in women with trauma histories who report a heightened propensity for NA and greater scores on measures of depression than women without trauma histories [2,22,23]. The present findings expand this information to women with BN+PTSD, perhaps, as other studies suggest, because of sensitivity to stimuli involving perceptions of threat, rejection, or criticism [23,24], all likely to be heightened in individuals with PTSD.

5.2 Research Question #2

Additionally, support was found for the second research question and hypothesis: individuals in the BN+PTSD group reported a greater daily frequency of binge eating and purging behaviors than those in the BN only group. Similar results were shown in an EMA study by [9], noting that childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was associated with a higher frequency of purging behaviors. In the present study 55% of participants in the BN+PTSD group reported CSA, and 85% of participants reported CSA, rape, or both, thus, indicating that most cases of PTSD were associated with interpersonal violence, often during childhood. Other studies have shown mixed findings for links between a history of abuse or trauma and the severity of eating disorder symptoms [2,3,4]. Perhaps the presence of diagnoseable PTSD, examined in the present study, is a more potent predictor of bulimic severity than a history of child trauma and reflects the affective dysregulation that accompanies PTSD, but does not always accompany the experience of trauma or abuse [25,26]. Nonetheless, with the use of EMA technology in the present study, with its accompanying sensitivity to capturing behavioral events in real time, individuals with BN+PTSD engaged in a greater frequency of bulimic behaviors than those with BN only.

5.3 Research Question #3

Partial support was found for the third research question and hypothesis in that NA significantly increased prior to binge eating and significantly decreased following binge eating for both groups (i.e., BN+PTSD, BN only), and did not differ between groups. Given this finding, it appears that binge eating may serve as a means to regulate NA in BN regardless of PTSD status [9,10]. Thus, both groups reported a similar NA trajectory in relation to the binge eating event. Both groups also reported decreased PA prior to binge eating and increased PA after binge eating, and like NA, the results did not differ for PA by group. These findings are similar to results found by [10], which showed that binge eating is associated with increases in NA and decreases in PA before a binge eating episode, and decreases in NA and increases in PA after a binge eating episode. Binge eating may then serve the function of regulating affect for participants in this study, but the relation between affect and behavior was not moderated by the presence or absence of PTSD.

Like binge eating, NA significantly increased prior to purging events and significantly decreased following purging events for both groups. Both groups also experienced a decrease in PA prior to purging events and an increase in PA following purging events. Group moderated the association between NA and time, indicating that the pattern of NA prior to and following purging differed for the BN+PTSD versus the BN only group. That is, unlike the BN only group, NA increased at a faster rate prior to purging and decreased at a faster rate following purging for those in the BN+PTSD group. Group also moderated the association between PA and time as the pattern of PA following purging differed by group, indicating that the BN+PTSD group showed a faster increase in PA after purging than the BN only group. For individuals in the BN+PTSD group, purging occurs after more rapid escalation of NA and is followed by a more rapid reduction of NA. In a complementary fashion, BN+PTSD participants also experience a more rapid increase in PA after purging than the BN only group, thus suggesting that PTSD modifies the functional relation between affect (i.e., NA, PA) and purging.

5.4 Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, the BN+PTSD group was rather small, including only 20 participants. Second, despite the ability to situate affect and behavior in time using EMA, the data are still self-report in nature and rely upon accurate reporting by participants. Furthermore, it is possible that participants may have omitted reports of binge eating and purging. Third, self-monitoring of momentary affect and behavior may have influenced the occurrence of such behaviors; however, previous EMA studies have shown minimal reactivity associated with the recordings [27].

6. Conclusion

The present findings support the importance of recognizing PTSD when interpreting the emotion-behavior relationship in individuals with BN. Individuals with BN+PTSD experienced a higher daily level of negative affect and a greater daily frequency of bulimic behaviors than those with BN only. Additionally, NA served as a trigger for binge eating for both individuals with BN+PTSD and those with BN only. For individuals with BN+PTSD, purging behaviors functioned differently as mechanisms for emotional regulation than in participants with BN only.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) award (MH59674).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dansky BS, Brewerton TD, Kilpatrick DG, O’Neil PM. The national women’s study: Relationship of victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder to bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;21:213–228. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199704)21:3<213::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleaves DH, Eberenz KP, May MC. Scope and significance of posttraumatic symptomatology among women hospitalized for an eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:147–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<147::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inniss D, Steiger H, Bruce K. Threshold and subthrehold post-traumatic stress disorder in bulimic patients: Prevalences and clinical correlates. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2011;16:e30–36. doi: 10.1007/BF03327518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzer SR, Uppala S, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Simonich H. Mediational significance of PTSD in the relationship of sexual trauma and eating disorders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewerton TD. The links between PTSD and eating disorders. Psychiatric Times. 2008;25:43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, victimization, and comorbidity: Principles of treatment. In: Brewerton TD, editor. Clinical handbook of eating disorders: An integrated approach. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 509–545. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tagay S, Schlegl S, Senf W. Traumatic events, posttraumatic stress symptomatology and somatoform symptoms in eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review. 2010;18:124–132. doi: 10.1002/erv.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders. 2007;15:285–304. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wonderlich SA, Rosenfeldt S, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG, Smyth J, et al. The effects of childhood trauma on daily mood lability and comorbid psychopathology in bulimia nervosa. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:77–87. doi: 10.1002/jts.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, et al. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel SG, Boseck JJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JA, Smyth J, et al. The relationship of momentary anger and impulsivity to bulimic behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muehlenkamp JJ, Engel SG, Wadeson A, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Simonich H. Emotional states preceding and following acts of non-suicidal self-injury in bulimia nervosa patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. Patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossotto E, Yager J, Rorty M. The impulsive behavior scale. Unpublished Manuscript. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanderlinden J, Vandereycken W. Trauma, dissociation, and impulse dyscontrol in eating disorders. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witte TK, Fitzpatrick KK, Joiner TE, Schmidt NB. Variability in suicidal ideation: A better predictor of suicide attempts than intensity or duration of ideation? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;88:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SPSS, Inc. Statistical software. Version 19. Chicago, IL: SPSS, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson KM, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Redlin J, Demuth G, et al. Psychopathology and sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:35–38. doi: 10.1023/A:1022007327077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chirichella-Besemer D, Motta RW. Psychological maltreatment and its relationship with negative affect in men and women. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2008;8:423–445. doi: 10.1080/10926790802480380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Neufeld RWJ, Densmore M, Stevens TK, Lanius RA. Social emotions and emotional valence during imagery in women with PTSD: Affective and neural correlates. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frewen PA, Lanius RA. Toward a psychobiology of posttraumatic self dysregulation: Re-experiencing, hyperarousal, dissociation, and emotional numbing. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1071:110–124. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wonderlich SA, Brewerton TD, Jocic Z, Dansky BS, Abbott DW. Relationship of childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1107–1115. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villarroel AM, Penelo E, Portell M, Raich RM. Childhood sexual and physical abuse in spanish female undergraduates: Does it affect eating disturbances? European Eating Disorders Review. 2011;20:e32–41. doi: 10.1002/erv.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein KF, Corte CM. Ecological momentary assessment of eating disordered behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;34:349–360. doi: 10.1002/eat.10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]