Abstract

Midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo exhibit a wide range of firing patterns. They normally fire constantly at a low rate, and speed up, firing a phasic burst when reward exceeds prediction, or pause when an expected reward does not occur. Therefore, the detection of bursts and pauses from spike train data is a critical problem when studying the role of phasic dopamine (DA) in reward related learning, and other DA dependent behaviors. However, few statistical methods have been developed that can identify bursts and pauses simultaneously. We propose a new statistical method, the Robust Gaussian Surprise (RGS) method, which performs an exhaustive search of bursts and pauses in spike trains simultaneously. We found that the RGS method is adaptable to various patterns of spike trains recorded in vivo, and is not influenced by baseline firing rate, making it applicable to all in vivo spike trains where baseline firing rates vary over time. We compare the performance of the RGS method to other methods of detecting bursts, such as the Poisson Surprise (PS), Rank Surprise (RS), and Template methods. Analysis of data using the RGS method reveals potential mechanisms underlying how bursts and pauses are controlled in DA neurons.

Keywords: Dopamine, Poisson Surprise, Gaussian Surprise, Template, Rank Surprise

1. Introduction

Spike trains of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo often exhibit three different firing patterns (Tepper et al., 1995). The cells normally fire tonically at a low rate, and speed up, firing a phasic burst when reward exceeds prediction (e.g. unexpected reward), or pause when an expected reward does not occur (Schultz et al., 1997; Tobler et al., 2003). Analysis of bursts and pauses requires accurate identification of the times when the bursts and pauses start, the number of spikes in them, and their durations. However, particularly for extracellular spike trains obtained from in vivo data, it is often unclear what should constitute a burst or a pause. This is partly due to the observation that many spike trains have varying background firing rates (i.e. nonstationarity), potentially reflecting periodic oscillatory activity (Kaneoke and Vitek, 1996; Gourevitch and Eggermont, 2007a).

For bursts, several types of detection methods have been proposed and their merits are evaluated in the spike train literature (Pauluis and Baker, 2000; Gourevitch and Eggermont, 2007b; Tokdar et al., 2010). Burst detection methods that are based on interspike interval (ISI) duration, with a criterion for a minimal number of spikes with short ISIs, are most frequently proposed and used (Grace and Bunney, 1984). Many of these methods provide descriptive measures, but do not offer any test of statistical significance. One of the most widely used methods of burst detection that does provide a test of statistical significance is the Poisson-Surprise (PS) method (Legendy and Salcman, 1985). This method calculates the probability that the number of spikes in a specified time interval would be observed in a Poisson process with the average firing rate of the entire spike train. A surprise value, S (negative logarithmic transform of the probability), measures how unlikely a cluster of spikes within a time interval, T, would occur by chance. However, this calculation assumes that the spike train follows a time-homogeneous Poisson process: that the ISIs are independent realizations from an exponential distribution. Spike trains often exhibit distinctly non-Poisson behavior (Koch, 1999; Gourevitch and Eggermont, 2007b) often because of a history dependence endowed by voltage-sensitive ion channels (Cateau and Reyes, 2006). This is especially problematic for neurons such as dopaminergic neurons, which are autonomously active and whose firing shows a strong autocorrelation. To accommodate non-Poisson behavior, Gourevitch and Eggermont (2007 a,b) proposed the Rank Surprise (RS) index, which uses the distribution of the sum of ISI ranks in a given interval to perform the chance calculation. This method improves upon the PS by removing the assumption that the spike train follows a Poisson process. However, a limitation of the RS index is that it is not powerful enough in detecting relatively short bursts, nor is it applicable to the detection of pauses.

In contrast to burst detection methods, fewer methods have been proposed for quantitative identification of pauses (Elias et al., 2007; Yartsev et al., 2009). The Pause Poisson Surprise method uses principles similar to the PS burst-detection algorithm. It evaluates the probability that a certain number of spikes or fewer appear within a time window sampled from a spike train of known average firing rate. A segment containing fewer spikes than would be observed in a Poisson process is called a pause period, and its probability (negative logarithmic transformed probability) is called the Pause Surprise. However, the Pause Surprise probability is calculated with the same average firing rate used in the PS burst-detection algorithm, and suffers from the same assumption that firing is a Poisson process.

In this paper we propose a new method, the Robust Gaussian Surprise Method, which overcomes the limitations of the Poisson Surprise and Rank Surprise methods. This method normalizes and combines interspike intervals from a group of spike trains, and distinguishes the baseline firing pattern from the burst or pause pattern using robust statistics. The identified baseline firing pattern exhibits a Gaussian distribution and the Robust Gaussian Surprise Method is applied to identify bursts and pauses simultaneously in individual spike trains of extracellularly recorded midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo. The Robust Gaussian Surprise Method successfully identifies bursts and pauses, even in cells exhibiting both bursts and pauses, and having widely varying background firing rates.

2. Methods

2.1 Notations and Definition

Following the notations in Gourevitch and Eggermont (2007 a,b), let tn be the occurrence time of the nth spike in a set of N + 1 spikes. The interspike interval ISIn is the time between two consecutive spike times, tn+1 and tn, that is, ISIn = tn+1 - tn. The spike time point process, {tn | n = 0, …, N}, is equivalently identified as a time series of interspike intervals, {ISIn | n = 1, …, N}, with the knowledge of the starting time, t0. In this paper, without loss of generality, we assume that t0 = 0 and treat the time series of interspike intervals, {ISIn | n = 1, …, N}, as the spike train. The spike train is called a renewal process when ISIs are independently and identically distributed. When the distribution is an exponential distribution, the corresponding spike time point process, {tn | n = 0, …, N}, is a called a Poisson process.

Gourevitch and Eggermont (2007 a,b) defined a burst as a set of spikes in which a certain number of consecutive small ISI values should not be observed if they were randomly and independently sampled from the “usual” distribution of ISIs for the recorded neuron. The “usual” distribution is defined as the distribution of ISIs without bursts and pauses. In this paper, we rename the „usual distribution' to refer to the central distribution. A pause is similarly defined as a set of spikes in which one or more consecutive large ISI values should not be observed if they were randomly and independently sampled from the central distribution of ISIs for the neuron. In statistical terminology, the bursts and pauses can be regarded as outliers from the central distribution, and could be isolated once the central distribution is identified.

2.2 How to find the Central Distribution and its Variance

Measuring of the variance of the central ISI distribution would be easy for spike trains with a small number of bursts or pauses, but some spike trains consist of a large number of bursts and pauses with a small number of ISIs within the central distribution. In such cases, the central ISI distribution is hard to reliably estimate, and therefore so are the bursts and pauses. We overcome the lack of the central ISIs in individual spike trains by combining all the spike trains for each experimental group in the study as follows:

Transform the ISIs to log (ISI). Often, the log-transformed ISIs exhibit distributional symmetry around a central location.

Center the log transformed ISIs around 0 by subtracting the central location, μ. In other words, log (ISI) - μ has the distribution centered around 0. From a spike train {log (ISIi), i = 1, …, N}, let be an estimated μ parameter. The spike train {log (ISIi) -, i = 1, …, N} is now centered around 0.

Because we need to describe the central distribution before detecting bursts or pauses, the central location parameter, μ, must be estimated from the full spike train using a method that is insensitive to outliers. The location parameter is usually estimated by the mean of the observed log (ISI)'s, but when there are bursts or pauses it is not reliable as a measure of the center of the central distribution. The presence of bursts and pauses in a spike train impedes estimation of the center because most estimators are heavily influenced by bursts and pauses, i.e., the outliers to the central distribution. A pause usually consists of one long ISI whereas a burst consists of many short ISIs, so the distribution of log (ISI) has asymmetric outliers. In the presence of such asymmetric outliers, we found that a midpoint between the extreme quantiles (upper and lower 5 percentile) of ISIs, which we call E-center, isolates bursts and pauses well. Though the E-center has more variability than the median or mean, it isolates bursts and pauses better, and is suited for our purpose in identifying them. However, when data consists solely of bursts, or pauses within baseline firing ISIs, the E-center is not a good estimator of the location of the central distribution. We propose a method that can accommodate all possible cases. In this paper, we propose a three-step procedure in estimating the central location of the central distribution as follows.

As the starting estimated center we use the E-center: the midpoint of top and bottom 100*p percentile of the log (ISI)s with p = 0.05. That is, E-center = F−1 (p) + F−1 (1-p), where F is the empirical distribution function of log (ISI)s.

The central set of log(ISI)s is defined as the set of log (ISI)s that falls within 1.64*MAD from the E-center where MAD is the estimate of standard deviation based on median absolute deviation of log(ISI). The Central Location 1 (C1-center) is the median of the central set {log(ISI)s | |log(ISIi) – E-center | ≤ 1.64*MAD}.

The Central Location, , is the median of the log(ISI)s that are within 1.64*MAD away from the C1-center. That is, = median {log(ISI)s | |log(ISIi) – C1-center | ≤ 1.64*MAD}.

Step 1 identifies the center of the central part in the presence of two forms of outliers: bursts, and pauses. Steps 2 and 3 locate the central portion of log (ISI)s, and its center using most robust location estimation “median” and most robust standard deviation estimate “MAD.”

For a spike train, the mean firing rate might change with time and so does the mean ISI. Hence, we propose the use of a moving central location of the central distribution of log (ISI) for a spike train instead of using a fixed central location such as μ. For each i, we choose the neighborhood of ISI's of size 2*Q+1, NQ (i) = {log (ISIi-q) | q = 0, ±1, …, ±Q} – where Q is the half-size of the moving window – and estimate the center, , of log (ISI)'s in NQ (i), as stated in the steps 1–3 above. The normalized spike train {log (ISIi) - , i, = 1, …, n} is now centered around 0 throughout the time. Of course, it is essential that the window used for this purpose be substantially longer than the duration of the longest burst or pause to be detected.

The window size should be large enough to capture the central location stably, but small enough to capture the local variation of the center. Since the Extreme center is highly dependent upon outlying values, the moving window should include several ISIs in the top and bottom 5 percentiles so that the estimate is more robust. We set Q, the half window size as the maximum of 20 and 0.2*N/2, where N is the number of spikes in the spike train, so the window size is twice of that + 1 (the point itself). This gives at least 20*2+1, i.e., from the central point left and right window sizes are 20. Therefore, at least 41 ISIs are used in estimating the Moving Central location, , at any time i. The minimum window size of 41 is chosen so that we would have at least two ISIs in the top 5 percentile and two in the bottom 5 percentile. When N is large the moving window size is about 20% of data, and we found it stabilizes the estimate of the central location while capturing the local variation well. We found that the 20% may be replaced by any percentage between 10 and 30% without much changing the results. In our simulated data analysis (Results section), we found that the change of the window sizes made very little (less than 0.3%) change to the mean number of bursts/pauses detected. When i is less than Q, or greater than n-Q – that is, around the beginning and the end of the spike train – a fixed window of size 2 * Q + 1 is used for stability.

2.3 Normalization Algorithm for Spike Trains

The normalization algorithm is summarized by the following steps:

Transform the interspike intervals to log interspike intervals. The spike train becomes {log (ISIi) | i= 1, …, N }.

Estimate the moving central location of log (ISI) for each spike train. For each i, we choose the neighborhood of ISIi of size 2*Q+1, NQ (i) = {log (ISIi-q) | q = 0, ±1, …, ± Q} and estimate the central location using 3 steps.

Normalize each spike train by subtracting from log (ISIi). The normalize spike train is the spike train {log (ISIi) - | i = 1, …, N} which is centered around 0.

The normalized log (ISI), NLISIi, is defined as log (ISIi) - .

Figure 1 illustrates the process of estimating the moving central location in 4 different spike trains. When there is only baseline firing (no bursts or pauses; figure 1a), the differences between the first update step (step 2) and the second update step (step 3) were negligible. The Central location still captures the center even when there are bursts only with baseline firings, or pauses only with baseline firing (figure 1c and 1d), or when there are bursts and pauses with baseline firing (figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Examples of the log (ISIi) along with E-center (black line), step 2 Update (green), and step 3 Central location (red) curves with the corresponding log (ISI). A. The pacemaker spike train, which did not have bursts or pauses. B. Spike train with bursts, pauses, and baseline firing. C. Baseline firing with bursts, and no pauses. D. Baseline firing with pauses, and no bursts.

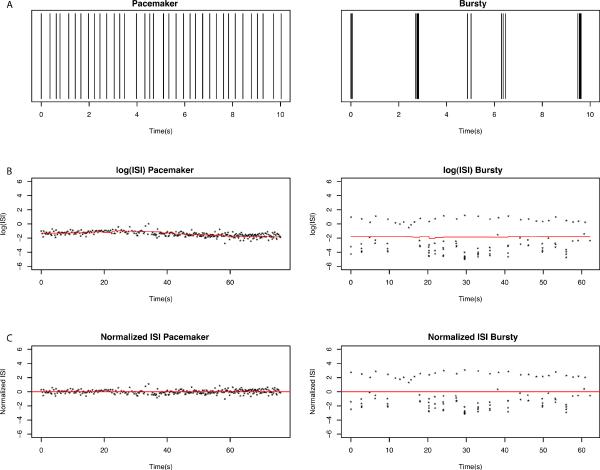

Figure 2 shows examples of the log (ISIi) along with E-center (red line) with the corresponding normalized log (ISI). The pacemaker spike train did not have bursts or pauses while the bursty spike train consisted almost entirely of bursts and pauses.

Figure 2.

A. Spike trains of the first 10 seconds from two in vivo extracellular recordings from anesthetized mice: one recording displaying a pacemaker pattern (left) and another displaying a burst pattern with pauses (right). Each vertical line represents one spike of activity from the recorded neuron. B. The ISI's are transformed into log (ISI), and the moving central location (red line) is determined. C. The log (ISI) is normalized so that E-center is centered at 0.

The Normalized log (ISI), NLISIi = log (ISIi) - measures the length of ISI relative to the corresponding mean ISI length of the central distribution in log units, and therefore does not have varying firing rates. As a result, we expect that the normalized log (ISI)s are centered around 0 with little rate changes along the time. This makes the different spike trains comparable to each other.

Since EC = exp () is an estimate of the expected ISI length of the central distribution, the expected length of ISI/EC becomes 1 if the spike train does not have any bursts or pauses. If there were bursts and pauses, the EC would be used as the value that separates the bursts and pauses from the central distribution, and NLISI would be used to measure the `pausiness' (extremely large NLISI value) or `burstiness' (extremely small NLISI value).

In addition to the central location, we need to estimate the variability of the central distribution to define the outliers (bursts and pauses) to the central distribution. There is no reliable way to estimate the variance of the central distribution from individual spike trains in which most ISIs belong to bursts and pauses. A more complete description of the central distribution of ISIs can be obtained by pooling information from the normalized ISI distributions from a group of spike trains. The pooled NLISIs from all the spike trains show more clearly three distinct patterns: the central part, burst part, and pause part. Once the central part of the pooled NLISIs is isolated, and the central distribution is estimated, bursts and pauses in each individual spike train can be easily identified as outliers to the pooled central distribution. Figure 2 shows examples of normalized spike trains with few bursts and pauses (pacemaker) and with many bursts and pauses (bursty). Figure 3 shows the three components of NLISIs pooled within each of the two groups: a Control group and a Knockout (KO) group (a group where NMDA receptors are genetically knocked out specifically in dopaminergic neurons: Slc6a3+/Cre;Grin1Δ/lox; see Zweifel et al., 2009 for details). The burst and pause NLISIs were identified using the Gaussian Surprise Method described later.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Pooled NLISIs. The pooled center part ISI's for each group (Control on left; KO on right) display the central distribution from which bursts and pauses in individual spike trains can be determined.

2.4 Central Distribution from the pooled NLISIs

The data we study include 18 spike trains from the KO mouse group, and 37 spike trains from the Control mouse group (the Slc6a3+/Cre; Grin1+/lox mice in Zweifel et al., 2009). The number of spikes ranges from 32 spikes (17.2 seconds) to 1272 spikes (289.74 seconds) for the KO mouse group, and 27 spikes (31.94 seconds) to 2267 spikes (749.41 seconds) for the Control mouse group.

We use pooled NLISIs within the two groups of spike trains to identify the central distribution of each group, and check the independence of the ISIs. We first combined all the NLISIs from the Control spike trains, and then did the same from the KO group. The central portion of NLISI data for each group was obtained by excluding possible outlier NLISIs. The thresholds for outliers were estimated by ±2.58*MAD, where MAD is an estimate of the standard deviation based on the Median Absolute Deviation of the pooled NLISIs. They correspond to the top 0.5 percentile and bottom 0.5 percentile when NLISIs have a normal distribution and no outliers are present. The MAD is an efficient and the most robust estimate of the standard deviation of the central part in the presence of outliers. The resulting distribution with outliers eliminated is referred to as the truncated distribution of NLISIs.

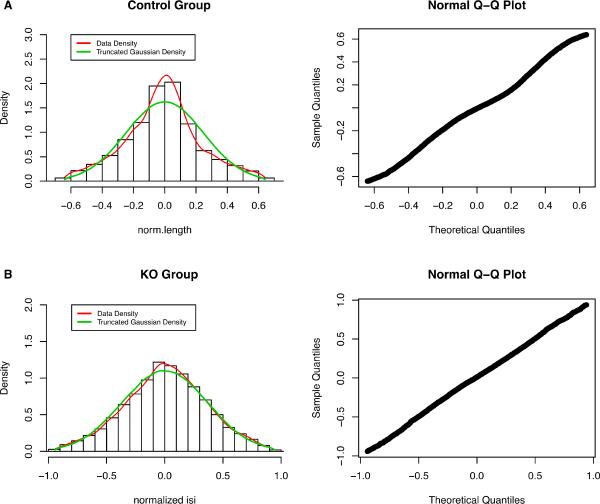

We compared the density of the truncated NLISIs with a truncated Gaussian distribution in Figure 4. The theoretical central parts were based on the truncated Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation σ, truncated at ±2.58* σ. The standard deviation, σ, is matched to the MAD of the pooled NLISIs. Figure 4 shows that the central part of the normalized log (ISI) data follows the Gaussian distribution in both groups.

Figure 4.

A. Histogram of Central NLISIs (left) and Normal Q-Q plot (right) for the Control Group. The data density (red line) is the nonparametric density estimate of truncated NLISIs, and the Truncated Gaussian Density (green line) is the corresponding theoretical density of the truncated Gaussian distribution. B. The histogram of Central NLISIs (left) and Normal Q-Q plot (right) for the KO group indicate that the NLISIs in the KO group are very close to the theoretical truncated Gaussian distribution.

We expect that 1% of data outside of truncation thresholds, ±2.58* σ, if the data were truly Gaussian without any outliers. In our examples, in the Control group, there were 12.2% of NLISIs outside the ±2.58* σ, and in the KO group, 4.1% were outside the range, suggesting the existence of bursts and pauses in both groups.

2.5 The Auto-Correlation between ISIs

From the pooled NLISIs, we sample bivariate data points, (NLISIi, NLISIi+1), for i = 1, 3, 5, …. The central part of the data is obtained by eliminating points that are 2.58 standard deviations, or farther, away from the center (0,0). If the underlying distribution is Gaussian, 1% of the data should be eliminated. Figure 5 shows a contour plot of the kernel density (Duong, 2007) estimates for the bivariate NLISI data. Independent Gaussian bivariate data would produce concentric circular contours. Figure 4 indicates that the KO group has circular contours while the Control group has a small positive correlation. The correlation of the Control group was 0.12 whereas the KO mouse group had a correlation of −0.08. The higher lag correlations (correlation between nlisii vs nlisii+k, k > 1) are much smaller than the lag 1 correlation, and so could be ignored. Since the observed correlations were small in both groups, we assume that the central part of the normalized ISI's are independent and have Gaussian distributions with mean 0. The proposed Gaussian Surprise method that detects bursts and pauses assumes that the `central' spike trains follow the renewal process with individual normalized log (ISI)'s having a Gaussian distribution. We observed that the auto-correlations between ISIs within bursts, and within pauses, are greater than 0.5, unlike the central distribution.

Figure 5.

Kernel Density Estimates of bivariate NLISIs among Control Group (left) and KO Group (right). Observed correlations are small in both groups (0.12 Control; −0.08 KO), indicating that the central parts of the normalized ISI's for both groups have independent Gaussian distributions centered about zero.

2.6 Robust Gaussian Surprise Method

We propose an algorithm for the Robust Gaussian Surprise Method as follows:

Set a pause-threshold and a burst-threshold for a burst and pause seed sets.

The pause-seed set is the set of all the NLISIs longer than the pause-threshold, and the burst-seed set is the set of all the NLISIs shorter than the burst-threshold.

From each NLISI in the seed set, extend it to a set of the consecutive string of NLISIs containing the seed NLISI until the string reaches the smallest P-value (or the largest Surprise value). This is done by adding an additional interval before or after the core interval in the initial step. If the added interval increases the P-value of the burst string or pause string, the interval is dropped and if the P-value decreases, the interval is added to the core strings.

At the end of add-drop process the resulting strings become the bursts, or pauses and the P-values for the burst or the pause are calculated. The identified strings are usually multiple and they may overlap each other. When the identified burst strings are overlapping, we select the string with the smaller P-value so that identified bursts are mutually exclusive. We apply the same rule to the pauses to have mutually exclusive pause intervals.

The pause-threshold is set as 99.5 percentile of the central distribution, and for bursts the threshold is set as 0.5 percentile of the central distribution. Since the normalized log (ISI) distribution is centered around zero, and the central distribution of NLISI is Gaussian, the pause-threshold (99.5 percentile of the central distribution) is estimated by 2.58*MAD; and the burst-threshold (0.5 percentile of the central distribution) is estimated by −2.58*MAD. Note that ±2.58 is the 99.5 and 0.5 percentiles of the standard normal distribution.

The P-value of the identified burst of q normalized ISIs, say {NLISIn, NLISIn+1, …, NLISIn+q−1}, is the probability of Tq being less than or equal to NLISIn + NLISIn+1 + … + NLISIn+q−1 where Tq is the sum of q independent identically distributed Gaussian random variables with mean μ, and standard deviation σ of the central distribution. The Tq has a Gaussian distribution with mean q*μ and standard deviation √q*σ. The P-value is calculated as:

The P value for the pause can be similarly calculated as:

The Robust Gaussian Surprise values GSB (Burst Surprise) and GSP (Pause Surprise) are defined as –log (P). Here the parameters μ and σ are estimated from the set of NLISIs that lie within 2.58*MAD distance from 0. To minimize the influences of possible remaining outliers, we use the most robust estimators such as median and MAD. In summary, we use two steps to generate the P-values. The first step is to take the central part of NLISIs, which lie between ±2.58*MAD. The second step is to use the robust estimators of the parameter μ and σ, based on the central portion of the NLISIs in calculating P.

2.7 Adjustment for Multiple Testing

In the detection of bursts and pauses, we perform tests for many candidate strings of consecutive intervals. In this case, a lack of adjustment for multiple testing could lead to hundreds of false positives. In this paper, we use the simplest multiple testing correction: the Bonferroni correction. The Bonferroni-adjusted P-value of the test is given as the minimum of P*K, and 1, where K is the number of the tests performed, and P is the unadjusted P-value. We accept the hypothesis that a string of consecutive ISIs is a burst or pause when the adjusted P-value is less than α, say 0.05. The number of KB tests performed for bursts, and the number of KP tests performed for pauses, are approximated by the number of identified bursts and pauses with unadjusted P-value < 0.05.

2.8 Simulation of spike trains

To compare our method with others we used simulated spike trains with known bursts and pauses. We simulated 20 sets of spike trains, where each set contained 10 simulated spike trains. We first applied the RGS method to the group of 37 spike trains from the Control mouse recordings, and identified bursts, pauses, and central baseline ISIs. We combined all the baseline ISIs, bursts, and pauses in the form of normalized ISIs, and used them in characterizing and simulating distributions of the baseline ISIs, bursts, and pauses.

Baseline normalized ISIs

The baseline ISIs (in normalized ISI units) are simulated from a Gaussian distribution. The mean parameter is set to be zero, and the standard deviation parameter is set to be the standard deviation of the observed baseline normalized ISIs from the Control mouse spike trains. We then trimmed them to the central 98 percentiles to eliminate potential pause and burst intervals.

Selection of burst and pause sizes

Using the average burst sizes (around 3.5), and pause sizes (around 1.5) from the spike trains from Control mouse recordings, we simulated the random Gaussian number with mean and standard deviation of the log of burst and pause sizes. The random bursts or pause sizes are determined by rounding up the exponential transformation of the generated random Gaussian number.

Simulation of burst and pause of a given size

A burst of a selected size, k, is a set of consecutive (k+1) spikes, which is also represented as a k-dimensional vector of normalized ISIs. This vector was simulated from the multivariate distribution (estimated from the set of all k-dimensional burst vectors of the normalized ISIs, the bursts of size k) from the Control mouse spike trains. We found that the k-dimensional lognormal distribution approximates the distribution of the negative of the k-dimensional burst vector. The sample mean vector and covariance matrix of the log(burst vectors of k-dimension) from the bursts of size k were used in generating k-dimensional random Gaussian vectors. The simulated random Gaussian vectors were then transformed back to normalized ISI units by the inverse transform function, f(v) = - exp(v).

A pause of length k is also represented as a k-dimensional vector of normalized ISIs. We found that log(pause vector) could be simulated by a k-dimensional Gaussian vector. We used the sample mean vector, and covariance matrix of the log(k-dimensional pause vectors of normalized ISIs) from the pauses of size k from the Control mouse spike trains in generating a random Gaussian vector. The simulated random Gaussian vectors were then transformed back to normalized ISI units by the inverse transform function, f(v) = exp(v).

Each simulated burst or pause was tested using the RGS method. When the adjusted P-value was greater than 0.05, it was eliminated from the list.

Note that we found that the observed correlations between normalized ISIs were around 0.5 for bursts and 0.65 for pauses. The generated baseline ISIs, bursts ISIs, and Pause ISIs were randomly mixed to make a spike train of normalized ISIs.

Random baseline firing rate

To allow different baseline firing rates among the spike trains, we added a random number representing the baseline firing rate (the mean of the log (ISI)) to the simulated normalized ISIs. We used random Gaussian numbers with mean and standard deviation obtained from the median (~ −1.26) and mad (~0.49) of the means of estimated central curves from the Control mouse spike trains.

Homogeneous Spike Train

After mixing baseline ISIs, bursts ISIs, and Pause ISIs; and adding a random baseline firing rate, we transformed them back to the original units by the inverse transform function, f(x) = exp(x).

The characteristics of the 10 simulated spike trains are summarized in Table 1. Spike trains 1–5 have bursts and pauses, and control spike trains 6–10 are devoid of bursts and pauses. We use spike trains 1–5 in evaluating false negative rates (or true positive rates), and spike trains 6–10 in evaluating false positive rates.

Table 1.

Simulated Spike Trains

| id | Spike Train | Baseline | Bursts | Pauses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bursts and Pauses with a small number of baseline ISIs ~300 ISIs |

50 baseline ISIs 25 % ISIs |

50 bursts with average length 3.5. 50% ISIs (~175 ISIs) |

50 pauses with average length 1.5. 25% pause ISIs (~75 ISIs) |

| 2 | Bursts and Pauses with a large number of baseline ISIs ~550 ISI |

300 baseline ISIs 54% ISIs |

50 bursts 32% (~175 ISIs) |

50 pauses. 14% (~75 ISIs) |

| 3 | Medium number of Bursts and Pauses with a large number of baseline ISIs ~530ISI |

400 baseline ISIs 75% ISIs |

25 bursts 17% (~90 ISIs) |

25 pauses. 8% (~40 ISIs) |

| 4 | Medium number of Bursts with a large number of baseline ISIs ~490 ISIs |

400 baseline firing ISIs 82% ISIs |

25 bursts 18% (~90 ISIs) |

0 pauses |

| 5 | Medium number of Pauses with a large number of baseline ISIs ~440 ISIs |

400 baseline firing ISIs 91% |

0 bursts | 25 pauses 9% (40 ISIs) |

| 6–10 | No bursts or pauses. 400 baseline firing ISIs |

400 baseline firing ISIs 100% |

0 bursts | 0 pauses |

3. Results

3.1 Simulated Data

All simulated spike trains are homogeneous spike trains. Figure 6 shows the summary results of the RGS method along with Poisson Surprise, Rank Surprise, and Template methods. In this, we used the criteria of adjusted P-value less than 0.05 in detecting the bursts and pauses for all the methods. We averaged the number of identified bursts and pauses from 20 simulated sets, and calculated the standard deviation, which was used in estimating the error bars. Error bars are 95 % confidence intervals for the True Positive Rates (TPR), and False Positive Rates (FPR). The TPR (also called Sensitivity) for bursts and pauses was calculated from each of the simulated data sets (Table 1) as the mean number of RGS-detected bursts or pauses divided by the known number of bursts or pauses, respectively, in each spike train. This rate was applied when the number of simulated bursts and pauses was non-zero. The False Negative Rate (FNR) can be obtained by the formula, FNR = 1 − TPR.

Figure 6.

Summary of True Positive, and False Positive rates for bursts and pauses for the RGS method along with Poisson Surprise, Rank Surprise, and Template methods. A. Burst Detection for Simulated Spike Trains. B. Pause Detection for Simulated Spike Trains

The rate of false positives is not so simple to calculate because the number of “non-bursts” or “non-pauses” is not well defined when the spike trains are devoid of bursts or pauses. We used the number of non-bursts as the number of ISIs divided by the average length, 3.5, of bursts that was used in the simulations, and the number of non-pauses as the number of ISIs divided by the average length, 1.5, of pauses that was used in the simulation. The False Positive Rate was calculated for the spike trains with no bursts (spike trains 5–10) or pauses (spike trains 4 and 5–10).

Figure 6a shows that the Robust Gaussian Surprise method clearly outperforms the other methods. The Rank Surprise method outperformed the Poisson Surprise method, but was far inferior to the RGS. Note that RGS has a slightly higher False Positive Rate (less than 3%) for bursts (simulations 5–10) than other methods, but the advantage of the other methods disappears when the true positive rate was compared (simulations 1–4). The Template method was comparable to the Rank Surprise method in True Positive Rate comparison of bursts, but the variance, reflected in the confidence intervals, was much higher than all the other methods.

In simulation number 1, 55% of simulated bursts were detected by the RGS while less than 35% were detected by the other methods. Since this spike train consisted primarily of bursts and pauses with only a small number of baseline firing ISIs, the separation of bursts and pauses from baseline firing may have been difficult without the use of a central distribution obtained from the combined central distributions of the combined spike train ISIs.

Figure 6b shows that the Robust Gaussian Surprise method clearly outperforms the Pause Surprise method in pause detection. Note that RGS has a slightly higher (less than 2%) False Positive Rate for pauses (simulations 4, and 6–10) than the Pause Surprise method (virtually 0%), but the true positive rates are 10 times higher (simulations 1–3, and 5).

We also used a non-parametric bootstrap method in generating baseline ISIs, bursts, and pauses based on the current experimental dataset. The results were very similar to our parametrically simulated data analysis, and were not reported here.

3.2 In Vivo Data

To test our method we used spike trains recorded from several mouse midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo. The central distributions for the control group and KO group were calculated from the normalized spike trains from the entire control group and KO group, respectively, and were used in identifying bursts and pauses in each individual spike train. To differentiate the significance of the bursts and pauses we use the following symbols in the spike train plot. The number of horizontal lines above the spike trains represents pause significance, and the number of horizontal lines below the spike trains represents burst significance. The number of lines corresponds to the Surprise values S > 3 (one line), S > 4.6 (2 lines), S > 6.9 (3 lines), S > 9.2 (4 lines) and S > 11.5 (5 lines), which correspond the P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001, respectively.

We used the spike train from a mouse in the control group as an illustration for Figure 7. This spike train contains 145 spikes within 51 seconds. We start with the template method (Grace and Bunney, 1984), which only defines bursts, and defines them as the consecutive ISI's starting with an ISI of less than 80 ms duration, and the following ISI's are added as long as their durations are less than 160 ms, though it does not provide any statistical significance, the Template method is easily applied to any spike train. Figure 7 shows the identified bursts by this Template method, and compares it to the Poisson Surprise and Robust Gaussian Surprise methods.

Figure 7.

Sample spike train analyzed using the Template (a), Poisson Surprise (b), and Robust Gaussian Surprise (c) methods. The top spike train displays the first 50 seconds while the bottom spike train shows the same spike train at higher temporal resolution (first 10 seconds). The horizontal lines above the spike trains represent pause significance, and the horizontal lines below the spike trains represent burst significance. A. The Template method detects bursts although no measure of significance is provided. This method also does not detect pauses. B. The Poisson Surprise method detects bursts and pauses although some pauses are not detected (see missed pauses between 8 and 10 seconds in bottom train). This method also relies on the background firing rate remaining stable. C. The Robust Gaussian Surprise method provides level of significance, and reliably detects all bursts and pauses even with a varying background firing rate.

3.3 Two Group Comparisons of bursts and pauses

3.3.1 Bursts

We used the RGS Method to estimate the number of bursts and pauses in each spike train, as described in the examples above. The burst or pause is defined as the cluster of consecutive ISIs whose adjusted P-values are less than 0.05. Data include duration of the spike train for each cell (tmax), mean E-center, and number of spikes and pauses. The mean number of bursts per second is modeled using a Poisson Regression. The estimated mean rate of individual spike train was dependent on the rate of the mean E-center, so we adjusted the effect by introducing the mean E-center as a covariate in the regression. The expected mean numbers (standard errors) of bursts per minute for the Control and KO groups were 11.85 (0.39) and 5.95 (0.40), respectively. Figure 9 shows the mean, and 95% confidence interval for the mean. The mean rate of the number of bursts for the KO group is significantly lower than that of the Control group (P< 2e-16) (50% of the Control group).

Figure 9.

Mean number of burst (left) and pauses (right) in the Control and KO groups. Both bursts and pauses are significantly reduced in the KO group.

3.3.2 Pauses

A similar Poisson regression model was built on the pause data. The expected mean numbers (standard errors) of pauses per minute for Control and KO groups were 13.14 (0.41) and 4.97 (0.36), respectively. Figure 9 shows the mean, and 95% confidence interval for the mean. Similar to the bursts, the expected mean rate of pauses for the KO group is significantly lower than that of Control group (P< 2e-16) (only 38% of the Control group).

3.3.3 Burst and Pause Comparison

The above analysis shows that the KO mouse group has a significantly lower number of both bursts and pauses. We compared the number of bursts and pauses for each spike train in Figure 10. The Control group had a correlation of 0.71. For the KO group the correlation was 0.20, and the difference of the correlations between the two groups was statistically significant (P-value < 0.03).

Figure 10.

Bursts and pauses were identified using the RGS method in spike trains from both the Control and KO groups. The number of pauses is correlated with the number of bursts in both the KO and Control groups.

4. Discussion

4.1 The Robust Gaussian Surprise Method

Bursting activity in neurons is thought to increase the reliability of transmission of information between neurons. Additionally, if the intraburst firing activity occurs at a specific resonant frequency, the postsynaptic neuron may be more likely to respond by firing (Izhikevich et al., 2003). Pauses in firing encode the timing of rebound bursts in cerebellar purkinje neurons (De Schutter and Steuber, 2009). Finally, spike trains of midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo exhibit both pauses and bursts (Tepper et al., 1995), and these are thought to have opposite psychological meaning (Schultz 2002). Analysis of bursts and pauses requires accurate identification of the times when the bursts and pauses start, the number of spikes in them, their durations, and sufficient statistical power to analyze how bursts and pauses change without the confounding changes in background firing rate (Gourevitch and Eggermont, 2007a).

Prior work has documented several methods for detecting bursts and pauses. For example, Grace and Bunney (1984) developed a simple yet very useful template method for burst detection in dopaminergic neurons. In the template method, bursts in dopaminergic neurons are defined as beginning with an ISI of less than 80 ms, and terminating with an ISI greater than 160 ms. This method has been very successful in identifying and evaluating bursts in dopaminergic neurons in a large number of studies. However, template methods have some limitations in that they produce neither statistical significance in burst detection nor any way to detect pauses. Other methods for burst and pause detection, such as the Poisson Surprise and Rank Surprise methods, overcome some of the limitations of the template methods, but lack robustness and statistical power, especially when a spike train contains both bursts and pauses.

In this study, we applied our Robust Gaussian Surprise (RGS) method to a group of spike trains obtained from extracellularly recorded midbrain dopaminergic neurons in vivo, and compared it to the methods mentioned above. We find that the RGS method performs favorably over the template, and Poisson and Rank surprise methods in detecting both bursts and pauses. We used the RGS method to compare two groups of mouse dopaminergic neuron recording spike trains, and found it to detect significant differences in both burst and pause patterns. To obtain the central distribution from each group, we used the pooled normalized, log transformed ISI's from all the spike trains within each group, and found the distribution of background firing rate (the Central Distribution). This central distribution is Gaussian, and we propose a Robust Gaussian Burst and Pause Detection algorithm that efficiently and effectively identifies bursts and pauses simultaneously in various spike trains, and overcomes the limitations of the Poisson Surprise and Rank Surprise methods, as well as the template method.

In our simulations, we generated 20 sets of 10 spike trains with known bursts and pauses. We showed that the Robust Gaussian Surprise method outperforms Poisson Surprise and Rank Surprise methods. Nevertheless, the RGS method proposed here has some limitations as well. If the individual spike train comprises a majority of bursts and pauses, establishing the central distribution becomes problematic since the baseline firing rate is not observed. We circumvent this problem when necessary by pooling the spike trains obtained from animals within the same group, with more reliable results (e.g. 70% detection power for simulation number 1, compared to less than 10% power for the other methods). The variance of the central distribution is then measured for the group, and bursts and pauses are identified in each individual spike train using that variance. Our RGS method also assumes that the central part of the distribution is Gaussian (in log units). Therefore, the central distribution must be checked, and the independence between ISI's in the central portion must be determined. Finally, the algorithm used here is not as simple to implement as a template method. Although the template method does not adjust for variations in background firing rate, in the spike trains analyzed here we find that a slight modification in the template definition for bursts in dopaminergic neurons (a template version 2.0) provides a robust burst detection comparable to our RGS method. As a usable definition it may be useful to define a burst as beginning with two (2) ISI's less than 80 ms instead of one. The end of a burst can still be defined as terminating with an ISI more than 160 ms.

4.2 Relationship between Bursts and Pauses

The RGS method allows the simultaneous analysis of bursts and pauses from a single spike train. A number of in vivo electrophysiological studies in anesthetized animals report that dopaminergic neuron bursts occurring spontaneously, or those triggered by electrical stimulation, are suppressed by local application of NMDA receptor antagonists (Overton and Clark, 1992; Chergui et al., 1993; Chergui et al., 1994; Christoffersen and Meltzer, 1995; Tong et al., 1996), suggesting that the majority of the tonic excitation driving bursts is NMDA receptor-mediated. In line with this, genetic inactivation of NMDA receptors selectively in dopaminergic neurons impairs spontaneous bursts, as well as those evoked by PPTg stimulation, as measured by the 80/160 template method (Zweifel et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011).

Using the same data from Zweifel et al., (2009) our analysis using the RGS method for bursts and pauses shows that the knockout group (NMDA receptor inactivation in dopaminergic neurons) indeed has half the number of bursts in comparison to control recordings, but also the number of pauses is reduced (around 38% of control). When comparing the number of bursts and pauses for each spike train in the control group (figure 9), we find that bursts and pauses are highly correlated (0.71 correlation in control mice), indicating that they generally appear together in the same spike train. In KO mice the correlation is significantly reduced to 0.20. In behaving animals bursts and pauses are evoked in different situations and have opposite psychological meanings (Overton and Clark, 1992; Hyland et al.; Schultz, 2002). If bursts are caused by phasic excitatory inputs, and pauses in firing are caused by separate phasic inhibitory inputs, then it is difficult to account for the reduction in number of pauses after inactivation of the excitatory NMDA receptors. However, the signal for burst timing can also originate from a GABAergic afferent via disinhibition (Hong and Hikosaka, 2008). In vivo, GABAergic inhibition is known to suppress bursting (Paladini and Tepper, 1999). A tonic inhibition that prevents bursting can be phasically removed, or reduced to allow tonically active glutamatergic afferents to drive a burst (Liu et al., 2005; Lobb et al., 2010). Under this scheme where bursts are induced by disinhibition, and pauses are induced by removal of excitation, genetic inactivation of NMDA receptors in dopaminergic neurons would then be expected to reduce both bursts (due to the loss of underlying tonic excitation), and pauses (due to the lack of excitation removal). A detection method capable of statistically comparing both bursts and pauses simultaneously, such as the RGS method proposed here, is necessary to be able to make this type of analysis possible.

Supplementary Material

This paper proposes a new method for analyzing spike trains that can detect bursts and pauses simultaneously

Bursts and pauses are detected independent of background firing rate

Normalized spike trains can be pooled within groups to obtain a central distribution even when there are only bursts and pauses

Simultaneous detection of bursts and pauses provides insight into the underlying mechanism driving bursts in dopaminergic neurons

Figure 8.

Sample spike train analyzed using the Template (a), and Robust Gaussian Surprise (b) methods. The top spike train displays the first 50 seconds while the bottom spike train shows the same spike train at higher temporal resolution (last 10 seconds). The horizontal lines above the spike trains represent pause significance, and the horizontal lines below the spike trains represent burst significance. A. The Template method detects more bursts although no measure of significance is provided. B. The Robust Gaussian Surprise method provides level of significance, and reliably detects all bursts and pauses even though the background firing rate is high.

Table 2.

Numbers of Bursts and Pauses with and without the Bonferroni correction (adjusted). The same spike train was analyzed with Poisson Surprise (PS), and Robust Gaussian Surprise (RGS) for bursts and pauses; and Template method, and Rank Surprise (RS) for bursts. The PS, RS, and RGS methods were also analyzed with adjustments for the Bonferroni correction. All bursts and pauses had a P value < 0.05. The minimum number of spikes in a burst is 2. The RGS method with adjusted P detected both bursts and pauses with much higher Surprise values than the other methods.

| Method | bursts | pauses |

|---|---|---|

| PS | 20 | 1 |

| RS | 10 | |

| RGS | 27 | 36 |

| PS adjusted | 7 | 1 |

| RS adjusted | 3 | |

| RGS adjusted | 25 | 36 |

| Template | 26 |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MH079276 to CAP, SNRP NS060658 to DK and CAP, MH084494 to CJL, and NS047085 to CJW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cateau H, Reyes AD. Relation between single neuron and population spiking statistics and effects on network activity. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:058101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.058101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chergui K, Suaud-Chagny MF, Gonon F. Nonlinear relationship between impulse flow, dopamine release and dopamine elimination in the rat brain in vivo. Neuroscience. 1994;62:641–645. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chergui K, Charlety PJ, Akaoka H, Saunier CF, Brunet JL, Buda M, Svensson TH, Chouvet G. Tonic activation of NMDA receptors causes spontaneous burst discharge of rat midbrain dopamine neurons in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen CL, Meltzer LT. Evidence for N-methyl-D-aspartate and AMPA subtypes of the glutamate receptor on substantia nigra dopamine neurons: possible preferential role for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neuroscience. 1995;67:373–381. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00047-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter E, Steuber V. Patterns and pauses in Purkinje cell simple spike trains: experiments, modeling and theory. Neuroscience. 2009;162:816–826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong T. ks: Kernel Density Estimation and Kernel Discriminant Analysis for Multivariate Data in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2007;21 [Google Scholar]

- Elias S, Joshua M, Goldberg JA, Heimer G, Arkadir D, Morris G, Bergman H. Statistical properties of pauses of the high-frequency discharge neurons in the external segment of the globus pallidus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:2525–2538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4156-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourevitch B, Eggermont JJ. A simple indicator of nonstationarity of firing rate in spike trains. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2007a;163:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourevitch B, Eggermont JJ. A nonparametric approach for detection of bursts in spike trains. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2007b;160:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA, Bunney BS. The control of firing pattern in nigral dopamine neurons: burst firing. J Neurosci. 1984;4:2877–2890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02877.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Hikosaka O. The globus pallidus sends reward-related signals to the lateral habenula. Neuron. 2008;60:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland BI, Reynolds JN, Hay J, Perk CG, Miller R. Firing modes of midbrain dopamine cells in the freely moving rat. Neuroscience. 2002;114:475–492. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izhikevich EM, Desai NS, Walcott EC, Hoppensteadt FC. Bursts as a unit of neural information: selective communication via resonance. Trends in neurosciences. 2003;26:161–167. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneoke Y, Vitek JL. Burst and oscillation as disparate neuronal properties. Journal of neuroscience methods. 1996;68:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(96)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C. Biophysics of computation : information processing in single neurons. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Legendy CR, Salcman M. Bursts and recurrences of bursts in the spike trains of spontaneously active striate cortex neurons. Journal of neurophysiology. 1985;53:926–939. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QS, Pu L, Poo MM. Repeated cocaine exposure in vivo facilitates LTP induction in midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2005;437:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature04050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb CJ, Wilson CJ, Paladini CA. A dynamic role for GABA receptors on the firing pattern of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:403–413. doi: 10.1152/jn.00204.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton P, Clark D. Iontophoretically administered drugs acting at the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor modulate burst firing in A9 dopamine neurons in the rat. Synapse. 1992;10:131–140. doi: 10.1002/syn.890100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladini CA, Tepper JM. GABA(A) and GABA(B) antagonists differentially affect the firing pattern of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons in vivo. Synapse. 1999;32:165–176. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990601)32:3<165::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauluis Q, Baker SN. An accurate measure of the instantaneous discharge probability, with application to unitary joint-even analysis. Neural computation. 2000;12:647–669. doi: 10.1162/089976600300015736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Getting formal with dopamine and reward. Neuron. 2002;36:241–263. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Martin LP, Anderson DR. GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition of rat substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons by pars reticulata projection neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3092–3103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03092.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler PN, Dickinson A, Schultz W. Coding of predicted reward omission by dopamine neurons in a conditioned inhibition paradigm. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10402–10410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10402.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokdar S, Xi P, Kelly RC, Kass RE. Detection of bursts in extracellular spike trains using hidden semi-Markov point process models. Journal of computational neuroscience. 2010;29:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong ZY, Overton PG, Clark D. Antagonism of NMDA receptors but not AMPA/kainate receptors blocks bursting in dopaminergic neurons induced by electrical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex. J Neural Transm. 1996;103:889–904. doi: 10.1007/BF01291780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Lei P, Li F, Wang D, Xie K, Wang D, Shen X, Tsien Joe Z. NMDA Receptors in Dopaminergic Neurons Are Crucial for Habit Learning. Neuron. 2011;72:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yartsev MM, Givon-Mayo R, Maller M, Donchin O. Pausing purkinje cells in the cerebellum of the awake cat. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2009;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.06.002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel LS, Parker JG, Lobb CJ, Rainwater A, Wall VZ, Fadok JP, Darvas M, Kim MJ, Mizumori SJ, Paladini CA, Phillips PE, Palmiter RD. Disruption of NMDAR-dependent burst firing by dopamine neurons provides selective assessment of phasic dopamine-dependent behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7281–7288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.