Abstract

The traditional role of bile acids is to simply facilitate absorption and digestion of lipid nutrients, but bile acids also act as endocrine signaling molecules that activate nuclear and membrane receptors to control integrative metabolism and energy balance. The mechanisms by which bile acid signals are integrated to regulate target genes are, however, largely unknown. Recently emerging evidence has shown that transcriptional cofactors sense metabolic changes and modulate gene transcription by mediating reversible epigenomic post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones and chromatin remodeling. Importantly, targeting these epigenomic changes has been a successful approach for treating human diseases, especially cancer. Here, we review emerging roles of transcriptional cofactors in the epigenomic regulation of liver metabolism, especially focusing on bile acid metabolism. Targeting PTMs of histones and chromatin remodelers, together with the bile acid-activated receptors, may provide new therapeutic options for bile acid-related disease, such as cholestasis, obesity, diabetes, and entero-hepatic cancers.

Keywords: FXR, TGR5, FGF15, Cyp7a1, post-translational modification, epigenetic, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, coregulators, liver metabolism

1. Introduction

Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and function as physiological detergents that facilitate the absorption and digestion of lipid-soluble nutrients (Russell 2003,Chiang 2009). Previously, bile acids were considered to play a simple dietary role after a meal, but it is increasingly appreciated that bile acids are endocrine signaling molecules that activate multiple nuclear and membrane receptor-mediated signaling pathways to regulate integrative metabolism and energy balance (Hylemon et al 2009,Thomas et al 2008,Houten et al 2006). Not surprisingly, therefore, these bile acid-activated signaling pathways have been attractive molecular targets for treating metabolic diseases (Thomas et al 2008,Modica and Moschetta 2006,Staels and Kuipers 2007,Cariou and Staels 2007,Zhang and Edwards 2008,Fiorucci et al 2009,Wagner et al 2011,Lefebvre et al 2009). Despite remarkable progress made in this field, our understanding of how bile acid signals are integrated to modulate transcription of genes is still limited.

Regulation of eukaryotic gene transcription is often mediated by epigenomic (also called epigenetic) changes mediated by environmental factors like nutrients. Epigenomics describes mechanisms by which gene activity can be altered without changes in the gene (DNA) sequences (Kouzarides 2007,Szyf 2009,Rosenfeld et al 2006,Jenuwein and Allis 2001,Rice and Allis 2001). Post-translational modifications (PTMs) of histones and chromatin remodeling are well-characterized epigenomic modifications (Kouzarides 2007,Narlikar et al 2002,Peterson and Workman 2000) that are catalyzed by transcriptional cofactors (also called coregulators) (Kouzarides 2007,Rosenfeld et al 2006,Kemper 2011). Importantly, these cofactors can function as cellular sensors that link metabolic status to gene transcription (Teperino et al 2010,Sassone-Corsi 2012,Iyer et al 2011,Cai and Tu 2011). Dozens of transcriptional cofactors have been reported to play important roles in epigenomic regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism (Table 1). It is, therefore, timely to survey the emerging role of transcriptional cofactors in epigenomic control of metabolism, with particular emphasis on the role of transcriptional cofactors as chromatin regulators in bile acid metabolism.

Table 1.

Epigenomic transcriptional cofactors controlling bile acid metabolism

| Transcriptional Cofactor |

Cellular Function | Epigenomic Regulation of Bile Acid Metabolism |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHP | Orphan nuclear receptor functioning as a transcriptional corepressor |

Functions as a key epigenomic coordinator in the regulation of bile acid metabolic pathways. Interacts with transcription factors and inhibits their transactivation by coordinately recruiting chromatin modifying cofactors, such as, HDACs, G9a, and Brm-Swi/Snf to target genes in response to bile acid signaling. |

(Miao et al 2009,Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004) |

| Brm | An ATPase of Swi/Snf Complexes |

Interacts with Shp and decreases the accessibility of chromatin in response to bile acids. Inhibits the expression of Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, Srebp-1c and Shp itself. |

(Miao et al 2009,Kanamaluru D. et al 2011) |

| Brg-1 | An ATPase of Swi/Snf Complexes |

Interacts with FXR and increases the expression of SHP by increasing accessibility of chromatin in response to bile acids. |

(Miao et al 2009) |

| G9a | Histone Lysine Methyltransferase |

SHP is exclusively localized in nuclease- sensitive euchromatin regions and directly interacts with G9a and HDAC1. Recruited to the Cyp7a1 promoter through interaction with the N-terminal region of SHP where it methylates H3K9 and inhibits expression. Also, required for SHP-mediated repression of HNF4α transactivation of Cyp7a1. |

(Fang et al 2007,Boulias and Talianidis 2004,Li et al 2010) |

| MLL3/4 | Histone Lysine Methyltransferases |

Recruited to the promoter of the Shp, Bsep, Mrp2, and Ntcp genes by FXR, in a ligand dependent manner, as part of the ASCOM complex. Increases transcription through tri- methylation of H3K4. Also act as coactivators of p53 which results in up-regulation of Shp. |

(Kim et al 2009,Kim et al 2011,Ananthanarayanan et al 2011,Lee et al 2009a) |

| PRMT1 | Arginine Methyltransferase |

Recruited to the Bsep and Shp promoters by FXR where it methylates H4 increasing gene expression. Also recruited to the Cyp3a4 gene, resulting in methylation of Arg-4 of histone H4. |

(Rizzo et al 2005,Xie et al 2009) |

| CARM1 | Arginine Methyltransferase |

Recruited to the Bsep promoter by FXR where it methylates H3R17 increasing gene expression. |

(Ananthanarayanan et al 2004) |

| HDAC1,2,3,7 | Histone Deacetylases |

Recruited to the Cyp7a1 promoter where it inhibits gene transcrption by deacetylation at H3K9/K14. Nuclear abundance of HDAC7 is increased after bile acid treatment. |

(Kemper et al 2004,Mitro et al 2007) |

| GPS2 | Bridging protein | Recruits NCoR and HDAC3 to Shp at the Cyp7a1 promoter and inhibits expression. Links HNF4α at Cyp8b1 promoter and FXR at a distant enhancer site and thereby, increases gene expression. |

(Sanyal et al 2007) |

| AMPK | AMP-activated Ser/Thr Kinase |

Phosphorylates a coactivator SRC-2 which increases Bsep gene transcription. |

(Chopra et al 2011) |

| SRC2 | P160 coactivator | Recruited to the Bsep promoter by FXR and increases gene transcription. |

(Chopra et al 2011) |

| P300 | Histone Acetyltransferase |

Recruited to the Shp promoter by FXR where it acetylates H3K9/14 increasing gene transcription. Also, acetylates FXR which decreases FXR transactivation. |

(Kemper et al 2009,Fang et al 2008) |

| SIRT1 | NAD+-dependent Histone Deacetylase |

Recruited to the Shp promoter by FXR deacetylating histones and decreasing gene transcription. Also, deacetylates FXR increasing its transactivation. Recruited by Shp to the Cyp7a1 promoter deacetylating H3 and H4 to repress LRH1- mediated transactivation. |

(Chanda et al 2010,Kemper et al 2009) |

1.1. Transcriptional cofactors as epigenomic chromatin regulators

Eukaryotic transcriptional regulation is achieved through actions of a number of transcriptional regulatory proteins that include DNA binding transcription factors, the basal transcriptional machinery, and multiple mediators and transcriptional cofactors (Rosenfeld et al 2006). Epigenomic regulation of genes is known to be affected by many environmental factors, including nutritional status, hormones, circadian rhythm, cellular stress, and viral/bacterial infection (Kouzarides 2007,Szyf 2009,Rosenfeld et al 2006,Jenuwein and Allis 2001,Rice and Allis 2001,Sassone-Corsi 2012). PTMs of histones and chromatin remodeling are well-characterized epigenomic mechanisms that fine tune gene activity by affecting the accessibility of genes to the transcriptional machinery (Kouzarides 2007,Narlikar et al 2002,Peterson and Workman 2000).

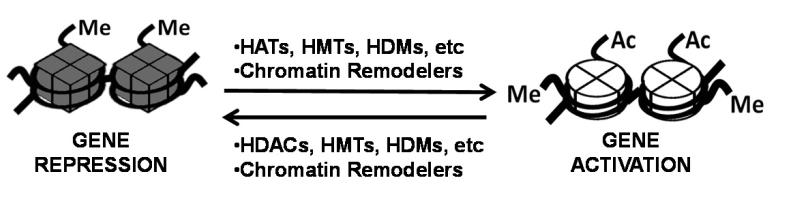

Eukaryotic genomic DNA is packaged into a highly organized structure, called chromatin. The primary structural units of chromatin are nucleosomes, which consist of an octamer of histone proteins and 146 bp DNA wrapped around the histone core. Nucleosomes hinder the access of transcriptional machinery and DNA binding transcriptional factors to genes. There are two classes of chromatin modifying cofactors that alter chromatin structure and gene activity (Fig. 2) (Kouzarides 2007,Szyf 2009,Rosenfeld et al 2006,Jenuwein and Allis 2001,Rice and Allis 2001).

Fig.2. Epigenetic regulation by chromatin modifying cofactors.

The chromatin modifying cofactors, HATs, HDACs, HMTs, HDMs, and chromatin remodelers, such as, ATP-dependent Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complexes, add or remove gene activation (ex: acetylation of H3K9/K14 and methylation of H3K4) or repression (ex: methylation of H3K9 and H3K27) histone PTMs and mediate chromatin remodeling. These events modulate accessibility of transcriptional machinery to DNA via altered chromatin structure, resulting in gene activation or repression.

The first class includes histone modifying transcriptional cofactors. These cofactors catalyze enzymatic PTMs of core histones, such as acetylation and methylation, in a reversible manner. These modifications result in increased or decreased transcription by modulating the accessibility of transcriptional factors and transcriptional machinery to DNA via altered chromatin structure. Histone acetylation is the most well-studied reversible epigenomic process, controlled by the opposing actions of two large families of enzymes, the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and the histone deacetylases (HDACs). HATs and HDACs covalently modify histones by adding or removing, respectively, acetyl groups on lysine residues of core histones. Histone acetylation and deacetylation generally correlate with gene activation and gene repression, respectively (Kouzarides 2007,Jenuwein and Allis 2001,Rice and Allis 2001). Histone methyltransferases (HMTs) or demethylases (HDMs) also reversibly add or remove methyl groups to lysine or arginine residues in core histones. In contrast to the general activation function of histone acetylation, histone methylation may result in either gene activation or repression depending on the amino acid residues that are methylated and the type of methylation, such as mono-di- and tri-methylation. For instance, methylation of histone H3 at Lys 4 (H3K4) is associated with gene activation, whereas gene repression is associated with methylation at H3K9 and H3K27 (Kouzarides 2007,Swigut and Wysocka 2007).

The second type of transcriptional cofactors that modulate chromatin structure and gene activity are ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers, such as Swi/Snf remodeling complexes (Workman and Kingston 1998,Aalfs and Kingston 2000,Hassan et al 2001,Saha et al 2006). The Swi/Snf complexes contain either Brm or Brg-1 as a central ATPase. These complexes use energy from ATP hydrolysis to remodel nucleosome structure by disrupting DNA and histone interactions, resulting in either transcriptionally activated accessible or transcriptionally repressive closed chromatin configurations.

Epigenomic regulation is particularly relevant for metabolism because the enzymatic activity of histone modifying cofactors, HATs, HDACs, HMTs, and HDMs, requires specific coenzymes, such as, acetyl CoA, nicotinamide dinucleotide (NAD+), S-adenosyl methionine, flavin adenine dinucleotide, or - ketoglutarate whose cellular levels fluctuate in response to the metabolic state. Importantly, the biosynthesis of these coenzymes is dependent on nutrient availability and cellular metabolism providing a functional link between metabolism and epigenomics . Accumulating evidence in the bile acid field has suggested that transcriptional cofactors catalyzing PTMs of histones and mediating chromatin remodeling have important roles in the epigenomic regulation of bile acid metabolism. In this review, we summarize the emerging role of transcriptional cofactors in epigenomic regulation, specifically highlighting their roles in hepatic bile acid metabolism in response to bile acid signals.

1.2. Bile acids as endocrine signaling molecules

Bile acids are detergent-like amphipathic steroid molecules that are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver (Russell 2003,Chiang 2009,Russell 1999). Bile acids have been traditionally considered as physiological detergents that simply facilitate the absorption and digestion of dietary lipids, but it is now increasingly appreciated that bile acids also function as important signaling molecules that control integrative metabolism and energy balance in the body (Hylemon et al 2009,Lefebvre et al 2009,Inagaki et al 2005,Watanabe et al 2006,Thomas et al 2009). Bile acids, together with cholesterol, phospholipids, and bilirubin, constitute bile that is stored in the gall bladder (Russell 1999,Moschetta et al 2004). When food enters the small intestine, bile is released to help solubilize and digest fat-soluble nutrients. Then, the majority of the bile acids are returned to the liver through enterohepatic recycling and signal the liver to regulate bile acid levels and to prepare for post-prandial metabolic responses (Russell 2003,Chiang 2009,Russell 1999).

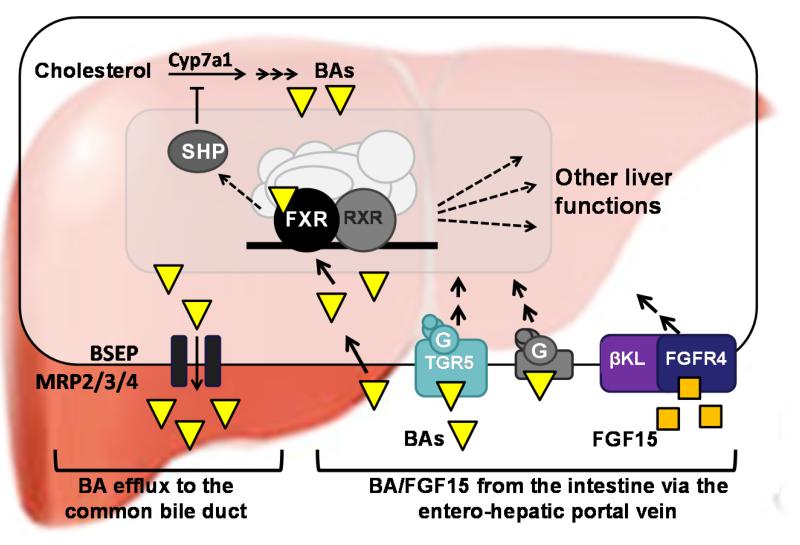

Bile acid signaling pathways are complex (Fig. 1). Bile acids activate multiple signaling pathways in the liver to control integrative metabolic regulation. Bile acids activate nuclear receptors, primarily the primary nuclear bile acid receptor FXR, G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) TGR5, and possibly other unidentified GPCRs (Hylemon et al 2009,Thomas et al 2008,Lefebvre et al 2009,Lee et al 2006). An in vivo gut-liver regulatory axis involving bile acid-activated mouse FGF15 (FGF19 in humans) signaling was also demonstrated (Inagaki et al 2005). After a meal, intestinal FXR is activated by bile acids and induces synthesis of the intestinal peptide hormone FGF15. The secreted FGF15 binds to a liver transmembrane receptor, FGF15 receptor 4 (FGFR4) and its coreceptor Klotho ( KL), and triggers cellular signaling kinase cascades to control fed-state metabolism (Inagaki et al 2005,Kir et al 2011). In addition, after a meal, activation of intestinal TGR5 by bile acids results in the secretion of GLP1, which stimulates secretion of insulin by pancreatic -cells (Thomas et al 2008,Thomas et al 2009). Activation of these multiple bile acid signaling pathways leads to altered expression of hepatic genes involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolic pathways. These findings, collectively, demonstrate that bile acids function as endocrine metabolic integrators that signal the liver to prepare for post-prandial responses.

Fig.1. Bile acid signaling pathways are complex in the liver.

Bile acids are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol by a series of enzymatic reactions, including the first and rate-limiting step catalyzed by Cyp7a1. Bile acids are secreted from the liver into the common bile duct by bile acid transporters, such as, BSEP, and MRP2/3/4, and together with cholesterol, phospholipids, and bilirubin, constitute bile that is stored in the gall bladder. In response to a meal, bile acids are released into the ileum and facilitate digestion of lipid-soluble nutrients. Almost all (95%) of the bile acids are returned to the liver through enterohepatic recycling. Returned bile acids activate FXR, which results in regulation of FXR target genes including the induction of SHP. Bile acids also bind to a membrane receptor, a GPCR protein, TGR5, and probably other unidentified GPCR(s). In the ileum, bile acid-activated FXR induces expression of the intestinal peptide hormone, FGF15, (FGF19 in humans). Then, FGF15 is transported to the liver via the hepatic portal vein and binds its membrane receptor complex, FGFR4 and the coreceptor βKlotho. Binding of bile acids and FGF15 to their membrane receptors triggers cellular kinase signaling cascades to regulate expression bile acid-responsive target genes in hepatocytes.

1.3. Epigenetic regulation of bile acid metabolism

Multiple epigenetic mechanisms operate in the regulation of bile acid metabolism. Of the cofactors involved in bile acid regulation (Table 1), Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) was shown to be an important epigenomic regulator of bile acid biosynthesis (Miao et al 2009,Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004,Boulias and Talianidis 2004,Chanda et al 2010). SHP does not directly catalyze enzymatic modifications of histones, but instead it coordinately recruits chromatin modifying transcriptional cofactors, such as, HDACs, G9a lysine methyltransferase, and the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex. The two central ATPases of Swi/Snf complexes, Brm and Brg-1, have distinct functional roles in the SHP-mediated feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis (Miao et al 2009). Histone methyltransferases, including MLL3/4 lysine methyltransferases of the ASCOM complex (Kim et al 2009,Kim et al 2011,Goo et al 2003,Ananthanarayanan et al 2011), CARM1 and PRMT1 arginine methyltransferases (Ananthanarayanan et al 2004,Rizzo et al 2005), and G9a lysine methyltransferase (Fang et al 2007,Boulias and Talianidis 2004,Li et al 2010), have been shown to have roles in the regulation of bile acid biosynthesis and transport. The importance of protein acetylation is evident the in the roles of HDAC7 (Mitro et al 2007) and GPS2 (Sanyal et al 2007) and the balance between p300 acetylase and SIRT1 deacetylase in regulation of bile acid synthesis (Kemper 2011,Kemper et al 2009). The intersection of epigenomic regulation and cellular signaling is demonstrated by the involvement of the AMPK/SRC2 axis in the regulation of bile acid transporter genes (Chopra et al 2011) and bile acid detoxification (Klaassen et al 2011,Cui et al 2010b). We will review these epigenetic mechanisms related to bile acid metabolism, as well as, important remaining questions for future research and the exciting possibility of targeting epigenomics in the treatment of bile acid-related diseases.

2. SHP functions as an epigenomic regulator in bile acid metabolism

SHP was originally discovered as an orphan nuclear receptor because of the presence of a putative ligand binding domain (Seol et al 1996). Unusually however, SHP does not contain a DNA binding domain and functions as a transcriptional cofactor, usually a corepressor, by interacting with a number of transcriptional factors including many nuclear receptors ( Lee et al 2000,Lee and Moore 2002,Johansson et al 2000,Johansson et al 1999). Excellent articles reviewing functional roles and mechanisms of SHP in physiology and disease have been recently published (Bavner et al 2005,Chanda et al 2008,Zhang et al 2011). Therefore, in this review, we will highlight function of SHP as an epigenetic regulator in bile acid metabolism. The functional role of SHP is best understood in the regulation of cholesterol 7 hydroxylase (Cyp7a1), the first and rate limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of bile acids from cholesterol (Russell 2003,Chiang 2009). SHP does not directly catalyze enzymatic modifications of histones, but instead, it coordinates the sequential recruitment of chromatin modifying transcriptional cofactors at the promoter of Cyp7a1 (Miao et al 2009,Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004). It has been shown that negative feedback regulation of bile acid biosynthesis is regulated through a cascade of actions by the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR and SHP (Lu et al 2000,Goodwin et al 2000). FXR, as the primary biosensor of bile acids, plays a central role in maintaining bile acid homeostasis by regulating bile acid target genes. FXR does not directly repress transcription of Cyp7a1, but instead, acts indirectly through the induction of SHP. In addition, elevated bile acid levels activate FXR-independent cellular signaling pathways to repress Cyp7a1 in the negative feedback regulation of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis (Chiang 2009,Hylemon et al 2009,Thomas et al 2008) .

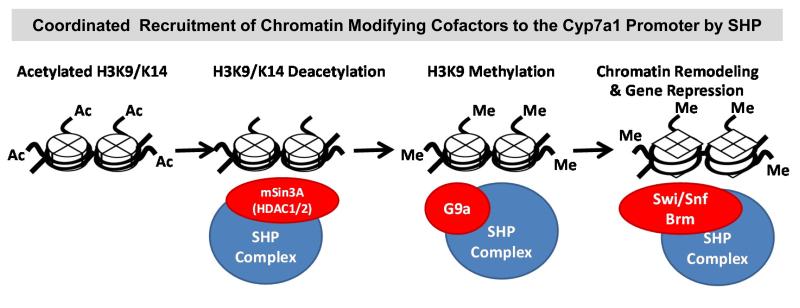

2.1. Coordinated recruitment of chromatin modifying cofactors by SHP

Using the Cyp7a1 gene as a model system, our group has elucidated the molecular mechanisms through which SHP mediates repression in the context of native chromatin (Miao et al 2009,Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004). In vivo nucleosome positioning and chromatin remodeling studies have revealed that nucleosomes at the Cyp7a1 promoter are regularly positioned and bile acid treatment does not result in gross structural changes, such as, nucleosome sliding or disruption (Kemper et al 2004). Instead, bile acid treatment resulted in decreased accessibility of DNA in nucleosome cores to nucleases at the promoter region, indicating that histone modification and chromatin remodeling occur at the Cyp7a1 promoter, which make the gene less accessible to transcription factors (Kemper et al 2004). Consistent with these initial findings, we further found that bile acid treatment results in increased interaction of SHP with chromatin modifying transcriptional cofactors, such as, mSin3A/HDAC1 corepressors, G9a lysine methyltransferase, and the Brm-containing Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex, and increased their recruitment to the Cyp7a1 promoter, resulting in chromatin modification and gene repression. Using siRNA approaches, along with chromatin and biochemical studies, Fang et al. found that SHP coordinately recruits these chromatin modifying cofactors to the promoter (Fig. 3) (Fang et al 2007). Histone deacetylation at H3K9/14 to remove a gene activation histone mark was mediated by the mSin3A-HDAC1/2 corepressor complex and was required prior to G9a-mediated methylation at histone H3K9, a gene repression histone mark (Fang et al 2007). Remarkably, these sequential histone modifications were necessary for recruitment of the Brm-containing Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex at the Cyp7a1 promoter to maintain the repressive chromatin domain (Miao et al 2009,Fang et al 2007). Relevant to these findings, recent studies from our group and others showed that a retinoid-related compound, 4-[3-(1-adamantyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl]-3-chlorocinnamic acid (3Cl-AHPC), is a synthetic ligand for SHP and enhances the repression activity of SHP by increasing interaction with these cofactors, mSin3A, HDAC1, and Brm (Miao et al 2011,Farhana et al 2007), suggesting that the orphan receptor SHP could act as a ligand-regulated nuclear receptor in the regulation of metabolic pathways.

Fig.3. SHP functions as a coordinator of epigenetic regulation of Cyp7a1.

In response to bile acid signaling, SHP mediates recruitment of chromatin modifying epigenomic cofactors, the HDAC1/2-containing mSin3A corepressor complex, G9a histone lysine methyltransferase, and the Brm-containing Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex to the Cyp7a1 promoter, resulting in sequential chromatin modification and gene repression. The recruited HDAC1/2 removes the gene activation histone mark, acetylation at H3K9/K14, G9a adds a gene repression histone mark, methylation at H3K9/K14, and the recruited Brm-containing Swi/Snf mediates chromatin remodeling at the promoter resulting in suppression of Cyp7a1 expression.

2.2 . Functional specificity of the Brm- and Brg-1-Swi/Snf complexes in SHP-mediated negative feedback regulation of bile acid biosynthesis

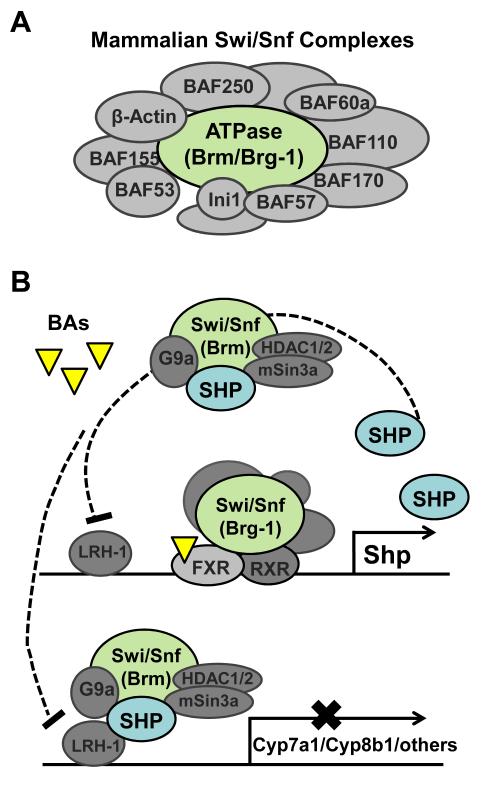

ATP-dependent Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complexes contain a central ATPase, either Brm or Brg-1, and varying additional Brm- or Brg-1-associated factors (BAFs) (Fig. 4A). Using the energy from ATP hydrolysis, these complexes alter nucleosome structure by disrupting DNA and histone interactions, resulting in either gene activation or repression. In some cases Brm and Brg-1 have been shown to be functionally redundant, but distinct actions have also been demonstrated for each in vivo (Kadam and Emerson 2003,Strobeck et al 2002,Flowers et al 2009,Reyes et al 1998). It was also shown that Brg-1 binds to proteins containing zinc finger DNA binding motifs, like nuclear receptors (NRs), while Brm interacts with ankyrin repeat proteins that are critical components of the Notch signaling pathway (Kadam and Emerson 2003). Moreover, mice lacking Brm or Brg-1 also exhibit different phenotypes. Brm-null mice developed normally but, interestingly, were 10-15% heavier than their littermates and showed altered cellular proliferation compared to wild type mice (Reyes et al 1998). In contrast, Brg-1-null mice were embryonic lethal and heterozygous Brg-1 null mice were predisposed to tumor formation (Reyes et al 1998,Bultman et al 2000,Roberts and Orkin 2004). These findings indicate that Brm and Brg-1 may have distinct gene-, tissue-, and developmental stage-specific biological functions.

Fig.4. Functional specificity of Brm- and Brg-1-containing Swi/Snf complexes in the FXR/SHP-mediated feedback inhibition of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis.

A) Mammalian Swi/Snf complexes are ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers comprised of a central ATPase, either Brm or Brg-1, and Brm- or Brg-1-associated factor (BAF) subunits. B) In response to bile acid signaling, the interaction between Brg-1 and FXR is increased, and occupancy of the Brg-1-containing Swi/Snf complex and FXR at the SHP promoter is increased, which results in chromatin remodeling and subsequent gene activation. FXR-induced SHP then interacts with LRH-1 at the Cyp7a1 promoter and inhibits transcription of Cyp7a1 by recruiting chromatin modifying cofactors, including the Brm-containing Swi/Snf complex and other chromatin modifying cofactors like HDACs and G9a, resulting in chromatin remodeling and subsequent gene repression of Cyp7a1. Interestingly, FXR-induced SHP also inhibits transcription of its own gene in a delayed negative auto-regulatory manner. Accessibility of the Shp promoter chromatin to endonuclease is initially increased after bile acid treatment, but, later is decreased, which correlates with the delayed recruitment of SHP and Brm-containing Swi/Snf and other chromatin cofactors to the Shp promoter.

In recent epigenomic studies, we have shown that Brm and Brg-1 of the Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complexes have distinct functions in the regulation of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis (Miao et al 2009). Bile acid treatment increased the interaction of Brg-1 with FXR and enhanced FXR-mediated transactivation of SHP, whereas increased Brm interaction with SHP resulted in enhanced SHP-mediated repression of Cyp7a1 and interestingly, auto-repression of Shp itself (Fig. 4B). Chromatin and biochemical studies further revealed that Brg-1 was recruited to the Shp promoter, resulting in transcriptionally active accessible chromatin, whereas Brm was recruited to both Cyp7a1 and Shp promoters, resulting in inactive inaccessible chromatin. These studies demonstrate that Brm and Brg-1 have distinct functions in the regulation of two key genes, Cyp7a1 and Shp, within a single physiological pathway, the feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis, by differentially targeting the key regulatory proteins, SHP and FXR. Since the inhibitory SHP complex also inhibits expression of its own gene, as well as the CYP7A1 gene, it is likely that chromatin modification and remodeling by the Brm-Swi/Snf complex may be a common mechanism by which SHP suppresses gene expression in other metabolic pathways. Consistent with this idea, we recently showed that bile acid treatment increased recruitment of SHP and Brm at other SHP target genes in mouse liver, such as, the bile acid biosynthetic gene, Cyp8b1, and the lipogenic gene, Srebp-1c (Kanamaluru D. et al 2011).

2.3. Role of G9a histone lysine methyltransferase in SHP-mediated repression of bile acid biosynthesis

G9a is a histone lysine methyltransferase which catalyzes mono- and di-methylation of histone H3K9 (Kouzarides 2007). Deletion of G9a is embryonic lethal and the embryos have severe growth retardation and H3K9 methylation is dramatically decreased (Tachibana et al 2002). G9a has been shown to play roles in many biological pathways and in particular, relevant to this review, Boulias and Talianidis for the first time demonstrated a functional role for G9a-induced histone methylation in transcriptional repression mediated by SHP (Boulias and Talianidis 2004). It was shown that SHP can associate with unmodified and methylated H3K9, but not with the acetylated H3K9 and that functionally interacts with G9a and HDAC1. Interestingly, a naturally occurring SHP mutant (R213C) that is associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans interacted less effectively with methylated histone H3K9 and showed decreased SHP repression activity (Boulias and Talianidis 2004).

Since SHP is a key regulator of hepatic bile acid synthesis, our group further examined whether SHP recruits G9a to the Cyp7a1 promoter, whether histone H3K9 methylation mediated by G9a occurs after bile acid treatment, whether a functional interplay between chromatin-modifying enzymes occurs in the native chromatin context, and importantly, whether G9a can regulate bile acid levels in vivo. Through chromatin, biochemical, and functional studies, we have found that G9a was recruited to the promoter, and subsequently, H3K9 was methylated in a SHP-dependent manner (Fang et al 2007). Overexpression of a catalytically inactive G9a dominant negative (DN) mutant inhibited H3K9 methylation and impaired the recruitment of the Brm complex. Inhibition of HDAC activity with trichostatin A (TSA) blocked deacetylation and also methylation of H3K9 at the promoter. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of a catalytically inactive G9a-DN mutant in mice, which blocks enzymatic activity of endogenous G9a in the liver, substantially decreased H3K9 methylation levels. Remarkably, these mice also showed elevated Cyp7a1 expression, enlarged gall bladders, and elevated bile acid pools, indicating a disruption of bile acid homeostasis. These studies demonstrate an in vivo role for G9a as an epigenomic regulator of bile acid homeostasis.

In regard to epigenomic histone H3K9 methylation at the Cyp7a1 promoter, a recent study performed by Chiang and colleagues have revealed an interesting link between glucose metabolism and bile acid biosynthesis (Li et al 2010). This group showed that chronically elevated glucose levels signal the liver to induce Cyp7a1 transcription through epigenomic modifications at the promoter, such as, increased H3K9 acetylation and decreased H3K9 methylation. Interestingly, Li et al. further showed that chronic exposure to high levels of glucose increased the nuclear abundance of ATP citrate lyase, resulting in increased acetyl CoA levels, which resulted in increased H3K9 acetylation by HATs and subsequently decreased H3K9 methylation mediated by G9a. This study suggests that abnormally regulated epigenomic control of bile acid biosynthesis may be important in pathophysiological hyperglycemic conditions.

3. Novel function of MLL3 histone lysine methyltransferase in bile acid homeostasis

Lee and colleagues identified the first mammalian activating signal cointegrator-2 (ASC-2)-containing coactivator complex (called ASCOM) (Goo et al 2003). This ASCOM complex includes histone methyltransferases MLL3 or MLL4, that methylate histone H3-lysine 4 (H3K4), a gene activation histone mark (Lee et al 2009a, Lee et al 2009b). Remarkably, the ASCOM complexes also contain UTX, an enzyme that removes the gene repression histone mark, H3K27 methylation. Therefore, ASCOM complexes have two distinct enzymes, MLL3/4 and UTX, which mediate dual transcriptional activation mechanisms by adding the activation mark, H3K4, and removing the repression mark, H3K27, respectively. This group further showed that MLL3 and MLL4 methyltransferases function as transcriptional coactivators of the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR and that these cofactors are recruited to the Shp promoter, resulting in H3K4 tri-methylation and gene activation (Kim et al 2009,Lee et al 2009b) (Fig. 5A). Expression of FXR target genes, including Shp, was partially impaired in MLL3 mutant mice that express a catalytically inactivated mutant form of MLL3, and, importantly, these mice showed disrupted bile acid homeostasis.

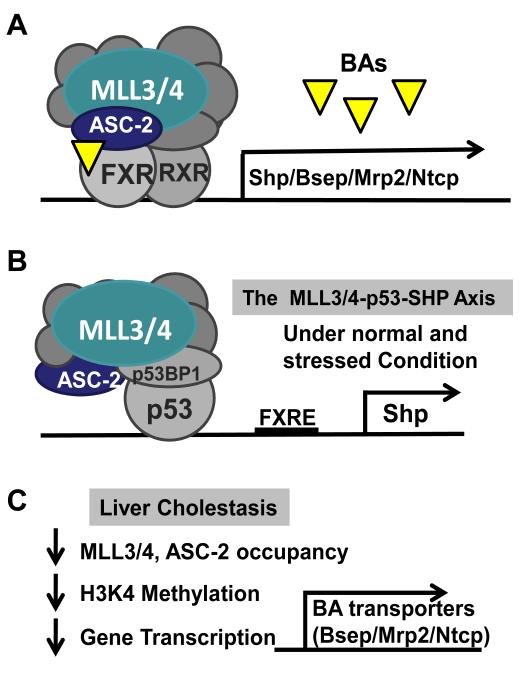

Fig.5. Role of MLL3/4 histone lysine methyltransferases of the ASCOM complexes in the regulation of bile acid homeostasis.

A) MLL3 and MLL4 methyltransferases within the ASCOM complexes function as transcriptional coactivators of bile acid-activated FXR. MLL3/4 and ASC-2, a key component of ASCOM complex as the nuclear receptor-interacting cofactor, are recruited to FXR target genes, including Shp, Bsep, Mrp2, and Ntcp, in response to elevated bile acid levels in hepatocytes and mediate methylation at H3K4 and gene activation. B) The MLL3/4-p53-Shp regulatory axis lowers bile acid levels under both normal and stress conditions. The well-known tumor suppressor p53 up-regulates Shp, a key inhibitor of hepatic bile acid biosynthesis, by direct binding to a p53 binding site upstream of the FXR binding site (FXRE) at the Shp promoter. The MLL3/4 methyltransferase of the ASCOM complex is recruited to p53 by a molecular adaptor, p53 binding protein 1 (p53BP1), and coactivates p53 transactivation through methylation at H3K4 at the Shp promoter. C) Under cholestatic conditions, occupancy of MLL3/4 and ASC-2 at the promoters of bile acid transporter genes, including Bsep, Mrp2, and Ntcp, is decreased. Consequently, methylated H3K4 levels are reduced and transcription of hepatic bile acid transporter genes is decreased.

Bile acids are cytotoxic molecules that could lead to liver damage and hepatocellular carcinoma. In recent studies, Lee and colleagues have identified novel functions of the MLL3/4 complexes as coactivators of the well-known tumor suppressor, p53 (Kim et al 2011,Lee et al 2009a). Consistent with this tumor-suppressive function of MLL3, kidney tumors developed in the MLL3 mutant mice (Lee et al 2009a) and different subunits of MLL3/4 complexes were shown to be mutated in human cancers (Balakrishnan et al 2007). Moreover, this group recently reported an intriguing metabolic regulatory axis that couples p53 to bile acid homeostasis (Kim et al 2011). They showed that p53 lowers hepatic bile acid levels primarily by up-regulation of SHP through direct binding to the promoter of the Shp gene in response to the treatment with the DNA damaging agent, doxorubicin, and further showed that the MLL3 in the ASCOM complex functions as a crucial hepatic coactivator of p53 in inducing expression of Shp in the negative regulation of bile acid synthesis (Kim et al 2011,Lee et al 2009a) (Fig. 5B). They further showed that MLL3 is recruited to FXR or p53 through different adaptor proteins, such as, ASC-2 or p53BP1, respectively (Fig. 5A, B), and coactivates FXR or p53-mediated transactivation of Shp, leading to reduced hepatic bile acid levels and bile acid pools. Collectively, these studies done by the Lee and colleagues have demonstrated a crucial role of MLL3/4 in maintaining bile acid homeostasis under physiological and pathological conditions.

Bile acid transporters, such as, bile salt export pump (Bsep) and multi-drug resistance protein 2 (Mrp2) play crucial roles in preventing liver cholestasis by mediating excretion of hepatic bile acids (Wagner et al 2011,Trauner and Boyer 2003,Cai and Boyer 2006,Suchy and Ananthanarayanan 2006). Consistent with a critical role of MLL3 methyltransferase in bile acid metabolism, in recent epigenomic studies, Ananthanarayanan and colleagues demonstrated that histone H3K4 methylation by MLL3 is critical for FXR activation of bile acid transporter genes (Ananthanarayanan et al 2011) (Fig. 5C). Using a microarray approach, this group discovered that expression of MLL3 methyltransferase was decreased in bile duct-ligated mice, a well-known mouse model of liver cholestasis (Ananthanarayanan et al 2011). Remarkably, from chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, this group further showed that H3K4 methylation and occupancy of MLL3 and ASC-2 of the ASCOM complex at these bile acid transporter genes were substantially decreased in the bile duct ligated cholestatic mice.

4. Role of CARM1 and PRMT1 arginine methyltransferases in bile acid metabolism

As a transcriptional regulator, the primary nuclear bile acid receptor FXR plays a central role in maintaining bile acid homeostasis by regulating every aspect of bile acid metabolism, including synthesis, detoxification, and transport of bile acids (Modica and Moschetta 2006,Zhang and Edwards 2008,Kemper 2011,Lee et al 2006,Fiorucci et al 2007,Choi et al 2006). FXR inhibits hepatic bile acid biosynthesis through the induction of SHP and also differentially regulates the expression of bile acid transporters (Modica and Moschetta 2006,Zhang and Edwards 2008,Kemper 2011,Lee et al 2006,Fiorucci et al 2007). Also, FXR promotes the efflux of bile acids from the liver by inducing expression of the bile acid transporters, Bsep and Mrp2, and the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein 3 (Mdr3). Ananthanarayanan and colleagues examined the epigenomic regulation of the Bsep gene and identified CARM1 as a transcriptional coactivator of FXR (Ananthanarayanan et al 2004). In response to treatment with an FXR agonist, FXR interaction with CARM1 was increased and occupancy of CARM1 and FXR was also increased at the promoter of the Bsep gene. Increased occupancy of CARM1 at the Bsep promoter resulted in increased methylation at Arg-17 of histone H3 and gene activation.

Another Arg methyltransferase, PRMT1, was also shown to function as a FXR coactivator. Fiorucci and colleagues reported that treatment with 6-ECDCA, a semi-synthetic FXR agonist, increased the interaction of FXR with PRMT1 and increased mRNA levels of the Bsep and Shp genes (Rizzo et al 2005). Treatment with 6-ECDCA also induced the recruitment of PRMT1 and accordingly, increased histone H4 Arg methylation at the promoter of Bsep and Shp genes. Tian and colleagues recently reported that PRMT1 also acts as an epigenomic cofactor in the regulation of the Cyp3a4 gene, one of the most important hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism of endobiotics and xenobiotics, by showing that PRMT1 is recruited to the Cyp3a4 gene, resulting in methylation of Arg-4 of histone H4 (Xie et al 2009). We recently showed that bile acid signaling increased SHP interaction with another Arg methyltransferase, PRMT5, and their recruitment to the SHP target genes, resulting in methylation of Shp at R57 (Kanamaluru D. et al 2011). Therefore, it will be interesting to test whether the recruited methyltransferases, such as PRMT1, PRMT5, and CARM1, also modifies non-histone metabolic regulators, such as, PGC-1 , SHP, FXR, LXR, SREBP-1c, as well as histones at target genes, which may further contribute to coordinated regulation of bile acid metabolism.

5. Role of HDACs in epigenomic regulation of bile acid biosynthesis

Mammalian HDACs have been categorized into three classes, class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3 & 8), class II (HDACs 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 & 10), and class III (SIRT1-7) (Haberland et al 2009). Recent studies have suggested that these HDACs play an important role in epigenomic regulation of bile acid and cholesterol metabolism. From biochemical and functional studies using in vitro and cell culture studies, Bae et al. and Gobinet et al. showed that SHP exerts repression activity by directly interacting with HDAC1 (Bae et al 2004,Gobinet et al 2005). Since SHP plays an important role in maintaining bile acid homeostasis, these studies suggest a potential role of HDACs in the epigenomic regulation of bile acid metabolism. Fang et al. further showed that bile acid treatment results in sequential recruitment of chromatin modifying cofactors, HDACs, G9a, and the Swi/Snf complex to the Cyp7a1 promoter and that SHP is important for the recruitment of these cofactors (Fang et al 2007). Moreover, increased occupancy of HDACs, such as, HDAC 1, 2, 3, and mSin3A and NCoR at the promoter was observed by our group and others (Fang et al 2007,Sanyal et al 2007). However, the order of recruitment and relative importance of these HDACs in Cyp7a1 repression were not examined in these studies.

Crestani and colleagues have examined the importance and functional specificity of HDACs in epigenomic regulation of CYP7A1 (Mitro et al 2007). ChIP assays, at two different time points (1 h and 16 h) after bile acid treatment, have revealed different occupancies of these HDACs, suggesting sequential recruitment of HDAC7, HDAC3, and HDAC1. Interestingly, the nuclear abundance of HDAC7 was increased in response to bile acid treatment. From gene expression studies along with siRNA approaches, this group concluded that HDAC7 is a key factor required for Cyp7a1 repression. Treatment with HDAC inhibitors, valproic acid and TSA, increased Cyp7a1 expression and reduced LDL cholesterol levels in LDLR knockout mice, an in vivo model of hypercholesterolemia. It will be interesting to see whether inhibition of nuclear localization of HDAC7 or downregulation of HDAC7 by siRNA would definitely impair the recruitment of other HDACs and impact levels of histone H3K9/K14 acetylation at the Cyp7a1 promoter. In addition, it will be important to test whether phosphorylation by bile acid-activated cellular kinase(s) is involved in the nuclear localization of HDAC7 .

In addition to the class I and II HDACs, Choi and colleagues recently reported the epigenomic control of Cyp7a1 by the class III HDAC, SIRT1 (Chanda et al 2010). SIRT1 is an NAD+ -dependent deacetylase that regulates hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism by deacetylating non-histone metabolic regulators as well as histones in response to nutritional deprivation (Kemper et al 2009,Rodgers et al 2008,Rodgers et al 2005,Li et al 2007,Ponugoti et al 2010). Chanda et al. showed that SIRT1 colocalizes specifically with SHP in vivo and directly interacts with SHP but it does not deacetylate SHP. Instead, SHP recruits SIRT1 to the Cyp7a1 promoter and consequently deacetylated histones H3 and H4 repress LRH-1-mediated transactivation. Moreover, using gain- and loss-of-function experiments, they showed that LRH-1-mediated transactivation of Cyp7a1 and Shp was significantly repressed by both SHP and SIRT1.

Although this review focuses on the role of epigenomic transcriptional cofactors in bile acid metabolism, an intriguing study has been recently reported by Lazar and his colleagues identifying a molecular mechanism that links circadian disruption and metabolic dysregulation (Feng et al 2011). They showed that during fasting (day time) conditions, HDAC3 is recruited to hepatic lipogenic genes through the direct interaction with a circadian regulator, Rev-erbα, and also with a corepressor, NCoR, which results in histone deacetylation and gene silencing. In contrast, under feeding (night time) conditions, the NCoR/HDAC3 complex and Rev-erbα are not recruited to lipogenic genes, resulting in histone acetylation and gene activation. Consistent with these results, liver-specific deletion of HDAC3 or Rev-erbα resulted in fatty liver, a major driver of metabolic dysregulation.

6. Functional role of GPS2 in bile acid biosynthesis

Involvement of a transcriptional cofactor, G protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2), in the regulation of bile acid biosynthesis has been recently demonstrated (Sanyal et al 2007). GPS2 was initially identified as an integral component of the NCoR/HDAC3 corepressor complex that inhibits the JNK pathway (Zhang et al 2002). GPS2 does not directly modify histones but it functions as a bridging protein that recruits histone modifying cofactors, such as, HDAC1, and HDAC3 to SHP bound to the bile acid target genes. Treuter and colleagues recently reported that GPS2 directly interacts with SHP, HDAC1, HDAC3, and NRs, such as, FXR, HNF-4, LRH-1, and LXR (Sanyal et al 2007,Venteclef et al ). Interestingly, GPS2 functions as a SHP cofactor and differentially regulates Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1, two important bile acid biosynthetic genes, by means of different interactions with NRs, LRH-1, HNF4α, and FXR (Sanyal et al 2007). GPS2 represses Cyp7a1 through inhibiting LRH-1 by serving as an adaptor protein for the recruitment of NCoR, HDAC1, and HDAC3 to SHP bound at the Cyp7a1 promoter. Interestingly, in contrast to GPS2 inhibition of Cyp7a1, at the Cyp8b1 promoter, GPS2 activates gene transcription by linking FXR at a distant enhancer to HNF-4 at the proximal promoter, thus mediating a long range enhancer-promoter interaction.

In addition to the role of GPS2 in the regulation of bile acid biosynthesis, this group recently discovered a novel function of GPS2 in linking inflammation and metabolism and elucidated the molecular mechanisms by which GPS2 inhibits inflammatory responses by facilitating accessibility of lipid-sensing NRs, such as, LRH-1 and LXR, to inflammatory target genes during the acute phase response in liver (Venteclef et al ). Moreover, this group has recently shown that GPS2 is required for transcription of the ABCG1 cholesterol transporter gene and cholesterol efflux from macrophage by triggering demethylation of histone H3K9, recruitment of the oxysterol receptor LXR, and assembly of transcriptional cofactors at the ABCG1 gene (Jakobsson et al 2009).

7. Epigenomic regulation of bile acid detoxification

In addition to activating the nuclear bile acid receptor FXR, bile acids are also known to activate other lipid-sensing NRs, such as, PXR and CAR (Ihunnah et al 2011,Xie et al 2001). Using a FXR and PXR double knockout mouse model, Guo et al. has demonstrated that FXR, PXR, and CAR function as transcriptional regulators of hepatic genes, including bile acid metabolizing genes, and, therefore, protect the liver against bile acid toxicity in a complementary manner (Guo et al 2003). These studies suggested that these NRs serve as redundant but distinct defense mechanisms against hepatic damage due to elevated toxic bile acids during cholestasis.

Excellent review articles summarizing epigenomic regulation of drug metabolizing genes, with emphasis on histone modifications, DNA methylation, and microRNAs, have been published (Klaassen et al 2011,Choudhuri et al 2010). Staying with the theme of this review, we will survey recent advances in understanding the role of histone modifications of bile acid metabolizing genes. It is well known that PXR plays a key role in the regulation of enzymes and transporters involved in metabolism of endobiotic molecules including bile acids as well as xenobiotic compounds (Ihunnah et al 2011,Xie et al 2001). From genome-wide ChIP-seq and ChIP-on-chip analyses, Klaassen and his colleagues discovered novel functions and epigenomic mechanisms by which PXR regulates direct genomic targets in mouse liver (Cui et al 2010b). Interestingly, this group showed that genome-wide PXR binding overlapped with the epigenomic mark for histone gene activation, H3K4 di-methylation, but not with histone gene repression mark, H3K27 tri-methylation. Furthermore, changes in mRNAs of most PXR direct target genes correlated with increased PXR occupancy at those genes after treatment with a PXR agonist. Ontogenic expression signatures of the 19 Glutathione S-Transferase (Gst) isoforms were also characterized and epigenomic mechanisms which regulate expression of these Gst genes during liver development were examined (Cui et al 2010a). These genome-scale studies suggest the functional importance of epigenomic histone and DNA modifications in the developmental stage-specific regulation of hepatic genes encoding drug metabolizing enzymes.

8. The AMPK-SRC-2 regulatory axis controlling the Bsep gene expression

AMPK is an AMP-activated protein serine/threonine kinase that functions as a master sensor for cellular energy levels and, therefore, plays a key role in the regulation of cellular and organismal metabolism (Kahn et al 2005). O’Malley and colleagues recently reported a role of the AMPK/SRC-2 axis in the regulation of whole body energy balance by modulating expression of hepatic bile acid transporter genes in in vivo studies (Chopra et al 2011). The energy-sensing kinase AMPK binds to, phosphorylates, and activates the transcriptional coactivator SRC-2, which results in increased expression of Bsep and promotes absorption of dietary fat from the gut (Chopra et al 2011). Importantly, hepatocyte-specific deletion of SRC-2 resulted in impaired fat absorption in the intestine, which the authors attributed to downregulation of AMPK- and SRC-2-mediated transcriptional regulation of the Bsep gene and subsequent impaired hepatic bile acid secretion into the gut. These effects were completely restored by replenishing intestinal bile acids or by genetically restoring the levels of Bsep. These in vivo studies reveal that the hepatic AMPK-SRC-2 axis functions as an energy sensing transcriptional switch, which can reset whole-body energy by promoting absorption of dietary fuel when cellular energy levels are low through transcriptional regulation of bile acid transporter genes. As AMPK was shown to activate transcription through direct association with chromatin and phosphorylation of histone H2B under metabolic stressed conditions (Bungard et al 2010), it will be interesting to test whether AMPK also phosphorylates histones at the Bsep gene.

9. Functional role of p300 and SIRT1 in dynamic transcriptional regulation

Recently, our group showed that p300 acetylase is an important transcriptional coactivator for FXR in Shp gene induction and that that p300 catalyzes acetylation of histones H3 K9 and K14, an active histone mark (Kemper et al 2009,Fang et al 2008). Interestingly, down-regulation of p300 altered expression of Shp and other metabolic FXR target genes involved in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, such that beneficial changes in lipid metabolism would be expected (Fang et al 2008). Consistent with these findings, a recent study showed that adenoviral-mediated overexpression of p300 in mice impairs lipid homeostasis and leads to severe hepatic steatosis (Bricambert et al 2010). We further showed that acetylation of FXR is dynamically regulated by p300 acetylase and SIRT1 deacetylase in response to bile acid signaling or by fasting and feeding (Kemper et al 2009). In response to bile acids or feeding, FXR interaction with p300 is increased and occupancy of FXR and p300 is increased at the Shp promoter, whereas that of SIRT1 is decreased, resulting in acetylation at H3K9/K14. Acetylation of histones by p300 is associated with gene activation and is probably the major factor in the transcriptional activation of the Shp gene. However, p300 also acetylates FXR, which results in the inhibition of heterodimerization with RXR and DNA binding. Interestingly, SIRT1 profoundly modulates FXR transcriptional signaling by deacetylation of both histones and FXR. On one hand, SIRT1 deacetylates histones, which is expected to result in transcriptional repression. On the other hand, SIRT1 increases FXR transactivation potential by deacetylating FXR. This apparently paradoxical effect may be an important mechanism to terminate transcriptional responses of FXR to a transient stimulus, which is essential in a dynamically regulated system to maintain homeostasis. Remarkably, acetylation of FXR is constantly elevated in fatty livers in dietary and genetic obese mice, further suggesting the importance of dynamic transcriptional responses to transient nutritional and hormonal signals to maintain homeostasis.

10. Important Questions

There are a number of important remaining questions about the epigenomic regulation of bile acid metabolism.

10.1. What are physiological roles of epigenomic cofactors in bile acid metabolism?

The in vivo functional role of chromatin modifying cofactors in bile acid metabolic pathways should be better established. Of these cofactors, studies of Brm-null mice would be especially intriguing because these mice exhibit heavier body weight, implying metabolic disorders (Reyes et al 1998). Since Brm is a central component of the SHP repression complex (Miao et al 2009), which is important for liver metabolism, it will be important to test whether bile acid homeostasis and abnormal metabolic outcomes are present in these mice. Moreover, it will be interesting to see whether Brm-null mice are more prone to metabolic syndrome in response to high fat diets. Although G9a homozygous null mice are embryonic lethal (Tachibana et al 2002), heterozygous mice have decreased expression of G9a and are viable. It would be important to determine whether these mice show impaired bile acid homeostasis as suggested from in vivo studies by adenoviral-mediated overexpression of a catalytically inactivate dominant negative G9a mutant (Fang et al 2007). Further, it will be interesting to ask whether metabolic defects other than those related to bile acid metabolism occur in these mice.

10.2. Does bile acid signaling alter levels and activity of epigenomic cofactors?

Recent evidence has suggested that transcriptional cofactors function as cellular sensors that can link metabolic status and transcription (Teperino et al 2010,Sassone-Corsi 2012,Iyer et al 2011,Cai and Tu 2011). Importantly, enzymatic activity of histone modifying cofactors, such as, HATs, HDACs, HMTs, and HDMs, requires specific coenzymes, such as acetyl CoA, NAD+, S-adenosyl methionine, and -ketoglutarate, whose levels fluctuate to reflect metabolic status. In this regard, it will be important to determine whether concentrations of these cofactors and their coenzymes fluctuate in response to bile acid signaling after a meal and whether there are abnormal levels of the cofactors and their coenzymes in bile acid-related diseases.

10.3. Are epigenomic PTMs of histones and chromatin remodeling at bile acid target genes altered in disease?

Bile acids activate multiple NRs- and membrane receptors-mediated signaling pathways in the liver. These events result in activation of cellular kinases, which phosphorylate histone and non-histone regulatory proteins (Hylemon et al 2009,Thomas et al 2008,Kemper 2011,Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004,Kanamaluru D. et al 2011). Therefore, it will be important to determine whether phosphorylation of histones by bile acid-activated kinase(s) would influence other epigenomic PTMs, such as acetylation/deacetylation and methylation/demethylation. Moreover, which of these multiple bile acid-activated signaling pathways plays the major role in hepatic fed-state metabolism needs to be established. It will be also important to determine whether abnormal cellular kinase signaling pathways result in abnormal PTMs of histones under bile acid-related disease conditions.

10.4. Do HDACs show functional redundancy or specificity in epigenomic regulation of bile acid metabolism?

Recent studies have shown that all three classes of HDACs play roles in the regulation of bile acid metabolism (Fang et al 2007,Kemper et al 2004,Chanda et al 2010,Li et al 2010,Mitro et al 2007,Sanyal et al 2007). Why are so many HDACs, such as HDAC1, 2, 3, 7 and SIRT1, involved in the negative regulation of bile acid metabolic pathways, are their functions redundant or unique, are some HDACs involved in gene activation, and do those HDACs control global or gene- and metabolic pathway-specific regulation? Recent HDAC studies using HDAC-knockout mice have revealed highly specific functions of individual HDACs in the regulation of heart development, cardiovascular growth, control of endothelial function, and cardiac muscle development (Haberland et al 2009). Conditional liver-specific HDAC-knockout mouse approaches will be useful in determining the in vivo function of individual HDACs in bile acid metabolism.

10.5. Are abnormal levels and activity of SHP associated with metabolic disorders?

Abnormal SHP function has been implicated in metabolic disorders, such as, fatty liver, obesity, and type II diabetes (Chanda et al 2008,Huang et al 2007,Boulias et al 2005,Park et al 2011,Park et al 2011,Park et al 2008,Wang et al 2005). In line with these results, we recently reported that bile acid-activated ERK transiently increases SHP stability by inhibiting proteosomal degradation but that abnormally elevated SHP levels were detected in obese mice, implying that dysregulated SHP levels are associated with pathogenesis (Miao et al 2009). If elevated SHP activity contributes to the pathology in fatty liver, development of small molecules that affect the interaction of SHP with chromatin modifying cofactors and, therefore, modulate SHP activity may be good pharmacological agents for treating metabolic disorders. Indeed, small molecules including 3Cl-AHPC that modulated SHP activity were shown to bind to the ligand binding domain of SHP and increase SHP activity by facilitating its interaction with mSin3A, HDAC1, and Brm (Miao et al 2011,Farhana et al 2007). Identification of SHP endogenous ligands and synthetic compounds that can activate or inhibit SHP activity will be important in the development of novel therapeutic targets for SHP-related human diseases, such as metabolic disorders and cancers (Bavner et al 2005,Chanda et al 2008,Zhang et al 2011,Zhang et al ) .

11. Future Perspectives

Epigenomics has emerged as one of the most promising and exciting areas for development of potential therapies for treating human diseases (Szyf 2009,Haberland et al 2009,Bolden et al 2006,Bolden et al 2006,Minucci and Pelicci 2006). Inhibitors of histone modifying transcriptional cofactors, such as, histone deacetylases and methyltransferases, have been developed as effective potential therapeutic options to treat human disease. For example, some inhibitors of HDACs have received FDA approval in the USA for the treatment of certain cancers, although these compounds showed some side effects in clinical trials. Therefore, it is likely to be a challenge, yet still important, to develop more specific compounds which can bind to and regulate crucial chromatin modifying epigenomic cofactors.

Bile acids are now appreciated as important metabolic integrators and endocrine signaling molecules that activate nuclear and membrane bile acid receptor pathways in the regulation of metabolism and energy balance (Hylemon et al 2009,Lefebvre et al 2009,Inagaki et al 2005,Watanabe et al 2006,Thomas et al 2009). Not surprisingly, there have been intensive efforts to identify natural and synthetic compounds modulating activity of the nuclear and membrane bile acid receptors, bile acid-activated signaling components, and other natural and synthetic compounds that can change amounts and composition of bile acids (Thomas et al 2008,Modica and Moschetta 2006,Staels and Kuipers 2007,Cariou and Staels 2007,Zhang and Edwards 2008,Fiorucci et al 2009). Therefore, combinatorial use of compounds modulating these multiple bile acid signaling pathways, together with epigenomic drugs that specifically target PTMs of histones or chromatin remodeling at bile acid target genes may present more effective and specific drugs for the prevention and treatment of bile acid-related human diseases, such as hepatobiliary diseases like cholestasis and cirrhosis, obesity, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and liver/intestinal cancers.

Highlights.

Bile acids function as endocrine signaling molecules that activate nuclear and membrane receptor signaling pathways to control integrative metabolism.

Transcriptional cofactors sense bile acid signals and modulate gene expression by mediating reversible epigenomic chromatin modifications.

Targeting epigenomic modifications, along with bile acid-activated receptors, may provide new therapeutic options for bile acid-related human disease.

Highlights.

Bile acids control integrative metabolism and energy balance in the body.

Bile acids are endocrine regulators that activate multiple signaling pathways.

Transcription cofactors sense the signals and mediate epigenomic control of genes.

Epigenomics may provide novel therapeutic options for bile acid-related disease.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those authors whose original works were not discussed in this review due to space limitations. We thank Byron Kemper for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant DK062777 and an ADA basic research award to J.K.K.

Abbreviations

- FXR

Farnesoid X Receptor

- PTM

post-translational modification

- NR

nuclear receptor

- DBD

DNA binding domain

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide 1

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Cyp7a1

cholesterol 7 hydroxylase

- Shp

Small Heterodimer Partner

- Bsep

bile salt export pump

- Mrp2

multi-drug resistance protein 2

- Mdr3

multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein 3

- Gst

Glutathione S-transferase

- FGF15

fibroblast growth factor 15

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- NAD+

nicotinamide dinucleotide

- TSA

Trichostatin A

- AMPK

AMP-activated kinase

- PRMT1

protein arginine methyltransferase 1

- MLL3/4

myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia 3/4

- CARM1

coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1

- ASC-2

activating signal cointegrator-2

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- GPS2

G protein pathway suppressor 2

- DN mutant

dominant negative mutant

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinases

- BA

bile acid

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aalfs J, Kingston R. What does chromatin remodeling mean? TIBS. 2000;251742:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthanarayanan M, Li S, Balasubramaniyan N, Suchy FJ, Walsh MJ. Ligand-dependent activation of the farnesoid X-receptor directs arginine methylation of histone H3 by CARM1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:54348–54357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthanarayanan M, Li Y, Surapureddi S, Balasubramaniyan N, Ahn J, Goldstein JA, Suchy FJ. Histone H3K4 trimethylation by MLL3 as part of ASCOM complex is critical for NR activation of bile acid transporter genes and is downregulated in cholestasis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G771–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y, Kemper JK, Kemper B. Repression of CAR-mediated transactivation of CYP2B genes by the orphan nuclear receptor, short heterodimer partner (SHP) DNA Cell Biol. 2004;231:81–91. doi: 10.1089/104454904322759894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan A, Bleeker FE, Lamba S, Rodolfo M, Daniotti M, Scarpa A, van Tilborg AA, Leenstra S, Zanon C, Bardelli A. Novel somatic and germline mutations in cancer candidate genes in glioblastoma, melanoma, and pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3545–3550. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavner A, Sanyal S, Gustafsson JA, Treuter E. Transcriptional corepression by SHP: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulias K, Katrakili N, Bamberg K, Underhill P, Greenfield A, Talianidis I. Regulation of hepatic metabolic pathways by the orphan nuclear receptor SHP. EMBO J. 2005;24:2624–2633. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulias K, Talianidis I. Functional role of G9a-induced histone methylation in small heterodimer partner-mediated transcriptional repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6096–6103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricambert J, Miranda J, Benhamed F, Girard J, Postic C, Dentin R. Salt-inducible kinase 2 links transcriptional coactivator p300 phosphorylation to the prevention of ChREBP-dependent hepatic steatosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4316–4331. doi: 10.1172/JCI41624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman S, Gebuhr T, Yee D, La Mantia C, Nicholson J, Gilliam A, Randazzo F, Metzger D, Chambon P, Crabtree G, Magnuson T. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungard D, Fuerth BJ, Zeng PY, Faubert B, Maas NL, Viollet B, Carling D, Thompson CB, Jones RG, Berger SL. Signaling kinase AMPK activates stress-promoted transcription via histone H2B phosphorylation. Science. 2010;329:1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1191241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Tu BP. On Acetyl-CoA as a Gauge of Cellular Metabolic State. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.010769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai SY, Boyer JL. FXR: a target for cholestatic syndromes? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10:409–421. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariou B, Staels B. FXR: a promising target for the metabolic syndrome? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda D, Park JH, Choi HS. Molecular basis of endocrine regulation by orphan nuclear receptor Small Heterodimer Partner. Endocr. J. 2008;55:253–268. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07e-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda D, Xie YB, Choi HS. Transcriptional corepressor SHP recruits SIRT1 histone deacetylase to inhibit LRH-1 transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4607–4619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:1955–1966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900010-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Moschetta A, Bookout AL, Peng L, Umetani M, Holmstrom SR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Identification of a hormonal basis for gallbladder filling. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1253–1255. doi: 10.1038/nm1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra AR, Kommagani R, Saha P, Louet JF, Salazar C, Song J, Jeong J, Finegold M, Viollet B, DeMayo F, Chan L, Moore DD, O’Malley BW. Cellular energy depletion resets whole-body energy by promoting coactivator-mediated dietary fuel absorption. Cell. Metab. 2011;13:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri S, Cui Y, Klaassen CD. Molecular targets of epigenetic regulation and effectors of environmental influences. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010;245:378–393. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JY, Choudhuri S, Knight TR, Klaassen CD. Genetic and epigenetic regulation and expression signatures of glutathione S-transferases in developing mouse liver. Toxicol. Sci. 2010a;116:32–43. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui JY, Gunewardena SS, Rockwell CE, Klaassen CD. ChIPing the cistrome of PXR in mouse liver. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010b;38:7943–7963. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Miao J, Xiang L, Ponugoti B, Treuter E, Kemper JK. Coordinated recruitment of histone methyltransferase G9a and other chromatin-modifying enzymes in SHP-mediated regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:1407–1424. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00944-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Tsang S, Jones R, Ponugoti B, Yoon H, Wu SY, Chiang CM, Willson TM, Kemper JK. The p300 acetylase is critical for ligand-activated farnesoid X receptor (FXR) induction of SHP. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:35086–35095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803531200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhana L, Dawson MI, Leid M, Wang L, Moore DD, Liu G, Xia Z, Fontana JA. Adamantyl-substituted retinoid-related molecules bind small heterodimer partner and modulate the Sin3A repressor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:318–325. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Liu T, Sun Z, Bugge A, Mullican SE, Alenghat T, Liu XS, Lazar MA. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Mencarelli A, Palladino G, Cipriani S. Bile-acid-activated receptors: targeting TGR5 and farnesoid-X-receptor in lipid and glucose disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Rizzo G, Donini A, Distrutti E, Santucci L. Targeting farnesoid X receptor for liver and metabolic disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2007;13:298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers S, Nagl NG, Jr., Beck GR, Jr., Moran E. Antagonistic roles for BRM and BRG1 SWI/SNF complexes in differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:10067–10075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808782200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobinet J, Carascossa S, Cavailles V, Vignon F, Nicolas JC, Jalaguier S. SHP represses transcriptional activity via recruitment of histone deacetylases. Biochemistry (N. Y. ) 2005;44:6312–6320. doi: 10.1021/bi047308d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo YH, Sohn YC, Kim DH, Kim SW, Kang MJ, Jung DJ, Kwak E, Barlev NA, Berger SL, Chow VT, Roeder RG, Azorsa DO, Meltzer PS, Suh PG, Song EJ, Lee KJ, Lee YC, Lee JW. Activating signal cointegrator 2 belongs to a novel steady-state complex that contains a subset of trithorax group proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:140–149. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.140-149.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin B, Jones SA, Price RR, Watson MA, McKee DD, Moore LB, Galardi C, Wilson JG, Lewis MC, Roth ME, Maloney PR, Wilson TM, Kliewer SA. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. 2000;61660:517–526. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo GL, Lambert G, Negishi M, Ward JM, Brewer HB, Jr., Kliewer SA, Gonzalez FJ, Sinal CJ. Complementary roles of farnesoid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor in protection against bile acid toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:45062–45071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AH, Neely KE, Vignali M, Reese JC, Workman JL. Promoter targeting of chromatin-modifying complexes. Front. Biosci. 2001;6:D1054–64. doi: 10.2741/hassan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houten SM, Watanabe M, Auwerx J. Endocrine functions of bile acids. EMBO J. 2006;25:1419–1425. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Iqbal J, Saha PK, Liu J, Chan L, Hussain MM, Moore DD, Wang L. Molecular characterization of the role of orphan receptor small heterodimer partner in development of fatty liver. Hepatology. 2007;46:147–157. doi: 10.1002/hep.21632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylemon PB, Zhou H, Pandak WM, Ren S, Gil G, Dent P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:1509–1520. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900007-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihunnah CA, Jiang M, Xie W. Nuclear receptor PXR, transcriptional circuits and metabolic relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:956–963. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, Luo G, Jones SA, Goodwin B, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer A, Fairlie DP, Brown L. Lysine acetylation in obesity, diabetes and metabolic disease. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011;90:39–46. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson T, Venteclef N, Toresson G, Damdimopoulos AE, Ehrlund A, Lou X, Sanyal S, Steffensen KR, Gustafsson JA, Treuter E. GPS2 is required for cholesterol efflux by triggering histone demethylation, LXR recruitment, and coregulator assembly at the ABCG1 locus. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Bavner A, Thomsen JS, Farnegardh M, Gustafsson JA, Treuter E. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP utilizes conserved LXXLL-related motifs for interactions with ligand-activated estrogen receptors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:1124–1133. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1124-1133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Thomsen JS, Damdimopoulos AE, Spyrou G, Gustafsson J, Treuter E. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP inhibits agonist-dependent transcriptional activity of estrogen receptors ERa and ERb. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:345–353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam S, Emerson BM. Transcriptional specificity of human SWI/SNF BRG1 and BRM chromatin remodeling complexes. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:377–389. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamaluru D, Xiao Z, Fang S, Choi S, Kim D, Veenstra TD, Kemper JK. Arginine methylation by PRMT5 at a naturally-occurring mutation site is critical for liver metabolic regulation by Small Heterodimer Partner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:1540–1550. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01212-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper JK, Xiao Z, Ponugoti B, Miao J, Fang S, Kanamaluru D, Tsang S, Wu S, Chiang CM, Veenstra TD. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metabolism. 2009;10:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper J, Kim H, Miao J, Bhalla S, Bae Y. Role of a mSin3A-Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex in the feedback repression of bile acid biosynthesis by SHP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:7707–7719. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7707-7719.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper JK. Regulation of FXR transcriptional activity in health and disease: Emerging roles of FXR cofactors and post-translational modifications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kim J, Lee JW. Requirement for MLL3 in p53 Regulation of Hepatic Expression of Small Heterodimer Partner and Bile Acid Homeostasis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011;25:2076–2083. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Lee J, Lee B, Lee JW. ASCOM controls farnesoid X receptor transactivation through its associated histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferase activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:1556–1562. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kir S, Beddow SA, Samuel VT, Miller P, Previs SF, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Shulman GI, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science. 2011;331:1621–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.1198363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Lu H, Cui JY. Epigenetic regulation of drug processing genes. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2011;21:312–324. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2011.562758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FY, Lee H, Hubbert ML, Edwards PA, Zhang Y. FXR, a multipurpose nuclear receptor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim DH, Lee S, Yang QH, Lee DK, Lee SK, Roeder RG, Lee JW. A tumor suppressive coactivator complex of p53 containing ASC-2 and histone H3-lysine-4 methyltransferase MLL3 or its paralogue MLL4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009a;106:8513–8518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Roeder RG, Lee JW. Roles of histone H3-lysine 4 methyltransferase complexes in NR-mediated gene transcription. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2009b;87:343–382. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)87010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Dell H, Dowhan DH, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Moore DD. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP inhibits hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 and retinoid X receptor transactivation: two mechanisms for repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:187–195. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.187-195.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Moore DD. Dual mechanism for repression of the monomeric orphan receptor liver receptor homologous protein-1 (LRH-1) by the orphan small heterodimer partner (SHP) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2463–2467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]