Abstract

Objective

To identify empirically-derived cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe pain

Setting

Community-based survey.

Participants

Convenience sample of 236 individuals with MS and pain.

Intervention

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

0-10 Numeric Rating Scale for pain severity (both average and worst pain) and Brief Pain Inventory for pain interference.

Results

The optimal classification scheme for average pain was 0-2 = mild, 3-5 = moderate, and 6-10 = severe. Alternatively, the optimal classification scheme for worst pain was 0-4 = mild, 5-7 = moderate, 8-10 = severe.

Conclusions

The present study furthers our ability to use empirically-based cutoffs to inform the use of clinical guidelines for pain treatment as well as our understanding of the factors that might impact the cutoffs that are most appropriate for specific pain populations. The results of the present study also add to the existing literature by drawing similarities to studies of other populations but also by highlighting that clear, between-condition differences may exist that warrant using different cutoffs for patients with different medical conditions. Specifically, the present study highlights that cutoffs may be lower for persons with MS than other populations of persons with pain.

Keywords: Pain, pain severity, pain interference, multiple sclerosis

Chronic pain is a common problem in persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) (1, 2). Among persons with MS, pain is often experienced in multiple sites (2). In some locations pain is only experienced during a short period of time, while pain in other sites may be persistent pain of either neuropathic or musculoskeletal origins, or some combination of the two.

In clinical research and in many clinical settings, pain intensity is commonly measured with numerical rating scales (NRS), where patients rate their pain intensity from 0 to 10 or 0 to 100 (3). However, treatment guidelines (e.g., cancer guidelines by the World Health Organization (4, 5) and Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (6)) are often developed based upon categorical ratings of pain (e.g., mild, moderate, severe). Despite the development of category-based treatment guidelines, there is no clearly defined mechanism for classifying pain intensity into these categories, which can make it difficult to determine when patients are experiencing the level of pain specified in treatment guidelines. This important gap has inspired a number of studies to gain an understanding of how NRS pain ratings relate to categorical pain ratings, and cutoffs for classifying pain intensity into discrete categories for a number of populations have been identified (7-16). However, the extent to which existing cutoffs are valid for classifying pain intensity in persons with MS is not known.

In a seminal study, Serlin and colleagues (13) evaluated NRS pain intensity ratings with respect to the interference of pain with daily activities among persons with cancer. They found that classifying mild pain as 0-4, moderate pain as 5-6, and severe pain as 7-10 was most consistent with the pattern of nonlinear associations between (worst) pain intensity ratings and pain interference in their sample.

This study has been subsequently replicated in samples of individuals with a variety of pain conditions and diagnoses. Patient groups that have yielded the same cutoffs as those found by Serlin and colleagues include those with post-operative pain (8) and low back pain (10). However, a number of studies have found variations in cutoffs, primarily surrounding whether 4 should be classified as mild or moderate and 7 should be classified as moderate or severe. For example, relative to the study by Serlin and colleagues, a study of patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy found a lower cutoff between mild and moderate pain (i.e., 0-3, 4-6, 7-10, for mild, moderate and severe) (11), while two replications in cancer populations (9, 15) reported a higher cutoff between moderate and severe pain (0-4, 5-7, 8-10). Beyond these between-group differences, additional studies have shown differences based on the type of pain measured. Cutoffs have been found to vary between general (0-3, 4-6, 7-10), phantom limb (0-4, 5-7, 8-10), and back pain (0-4, 5-6, 7-10) (7). Thus, despite some consistencies across populations for some intensity ratings, research shows that the best classification scheme varies to some extent as a function of patient population and type of pain measured. It is unclear, however, which scheme is most useful for persons with MS and chronic pain.

As research on pain cutoffs has evolved, Anderson (17) recommended that researchers consider cutoffs for both average pain and worst pain, given (1) the variability of pain for many patients and (2) that cutoffs may vary as a function of the pain intensity domain being considered. Using average pain is likely to adequately measure pain severity among persons who experience stable pain, but asking patients to rate worst pain in addition to average pain could provide additional critical information in individuals whose pain is highly variable. However, thus far, results are mixed: Cutoffs have not varied for average vs. worst pain for patients with cancer (9) or diabetic peripheral neuropathy (11), but the cutoff between moderate and severe pain has been found to be one point lower for “average” vs. “worst” pain in patients with primarily musculoskeletal pain (0-3, 4-5, 6-10 for average and 0-3, 4-6, 7-10 for worst pain in neck pain patients (14) and 0-3, 4-6, 7-10 for average and 0-3, 4-7, 8-10 for worst pain in veterans (16)).

The principle aim of the study was to identify the optimal classification scheme for average and worst pain for individuals with MS, using the method described by Serlin and colleagues (13). Secondary aims included determining if the schemes would be the same for measures of average and worst pain intensity, and assessing how the optimal classification scheme for individuals with MS relates to those identified in other patient populations (7-16).

METHODS

Procedures

Participants included in the present study participated in a multi-phase postal survey study of pain in persons with MS. All study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

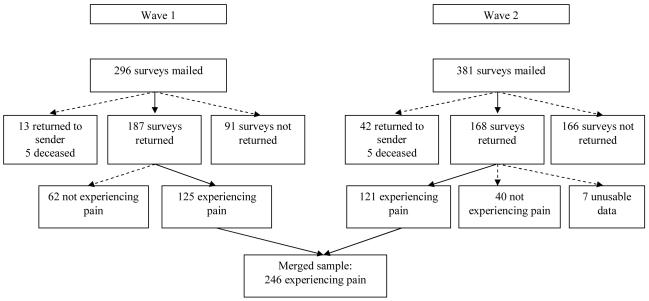

The subset of participants considered for the present study came from two waves of recruitment and survey completion, as both groups completed the relevant measures, were recruited through a similar method, and were independent samples with no repeat participants. Previous publications have reported on data from this same study (1, 18, 19), but neither of the previous papers addressed the questions that were the focus of the current paper.

Participant recruitment is depicted in Figure 1. In both samples, the majority of participants were randomly selected from a list of previous participants in research conducted by the University of Washington’s Multiple Sclerosis Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (MSRRTC) who indicated an interest in participant in future research and the remainder self-referred to study staff via fliers or other ongoing studies. In the first wave, surveys were mailed to 296 participants from September 2002 to October 2004. We excluded 18 participants who could not be reached (survey was returned to sender or participant was deceased), leaving 278 participants who we presume received surveys. A total of 187 individuals (67.3%) returned surveys, 125 of whom were experiencing pain. In the second wave, surveys were mailed to 381 individuals from April 2005 to June 2007. In this sample, 47 participants could not be contacted, resulting in a presumed sample of 334 participants. A total of 168 surveys were returned (50.3%), although 7 contained unusable data. Of this sample, 121 participants were experiencing pain. In sum, there were 348 usable surveys, with 246 (70.7%) participants reporting that they were experiencing pain. Participants completing the survey were paid $25 for their time.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of participants

Measures

Demographic

Participants were asked to provide information about participant sex, age, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, and marital status.

Pain presence and pain intensity

Participants in the present study were participants who affirmed that they were currently experiencing pain. Participants were then asked to consider their pain over the past week and provide 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as it could be) NRS ratings for the average pain and worst pain. The NRS has been validated extensively, with a large body of research supports the reliability and validity of this measurement approach (20).

Pain interference

Pain interference was assessed using the 12-item Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (19). This version of the BPI has evolved from the original 7-item measure (21, 22) and is a valid and reliable measure of pain interference in persons with MS (19). Participants were asked to provide 0 (does not interfere) to 10 (completely interferes) ratings of the extent to which their pain interferes with general activity, mood, mobility, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, enjoyment of life, self-care, recreational activities, social activities, communication with others, and learning new information or skills.

Data analysis

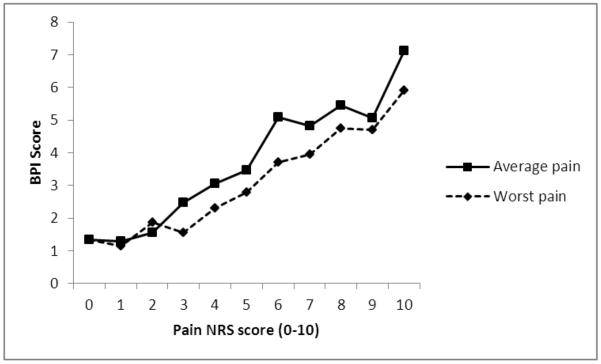

We employed the statistical method detailed below, which was the same method that was used by Serlin and colleagues (13) and replicated in subsequent research (7-16). In addition, we examined cutoffs for both average and worst pain, as recommended by Anderson (17). To determine the boundaries for mild, moderate, and severe pain among persons with MS, we tested five classification schemes each for average and worst intensity. Four of the classification schemes were used with both average and worst pain, and were selected based upon the existing literature (7-16); one additional classification scheme was chosen each for average and worst pain based upon apparent nonlinear increases in BPI score during visual inspection of the data that is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Average pain interference level at each level of pain intensity for both average and worst pain

We named the classification schemes based on the upper values of the mild and moderate categories. The four schemes identified in the literature (7-16) were: cutpoints (CP) 3,6 classified mild = 0-3, moderate = 4-6, and severe = 7-10; CP 3,7 classified mild = 0-3, moderate = 4-7, and severe = 8-10; CP 4,6 classified mild = 0-4, moderate = 5-6, and severe = 7-10; and CP 4,7 classified mild = 0-4, moderate = 5-7, and severe = 8-10. The additional classification scheme based on visual inspection of the data for average pain was CP 2,5 (mild = 0-2, moderate = 3-5, severe = 6-10) and for worst pain was CP 3,5 (mild = 0-3, moderate = 4-5, severe = 6-10).

We conducted ten (five for the five average pain classification schemes and five for the five worst pain classification schemes) analyses of variance (ANOVA) to identify the best classification scheme for mild, moderate, and severe pain, with pain classification group as the independent variable and pain interference (BPI) as the dependent variable. A significant F value was indicative of significant differences between the three pain severity groups on pain interference. Consistent with the method suggested by Serlin et al. (13), we determined that the highest F value was indicative of the classification scheme that best identified the mild, moderate, and severe pain groups.

RESULTS

Participants included in this study’s analyses were 246 participants with MS who indicated that they were experiencing pain from both study waves. The mean age was 52.4 (SD = 11.5; range = 19-86) years. Participants were primarily females (78.6%) and Caucasian (98%). The majority of participants in both samples had completed at least some college education (54.3%), and 98.3% had either completed high school or earned their GED. The largest group of participants was on disability (48%), with 18% working full-time and 10% working part-time.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the 348 participants who returned surveys, demonstrating that the participants with pain were of similar characteristics to participants without pain, and that the two groups of participants with pain were also similar to each other, with the following statistically significant exceptions: (1) the second sample of participants with pain had a mean age of 3.28 years older than the first sample; (2) a higher percentage of participants with pain were on disability relative to participants without pain; and (3) a higher percentage of participants without pain graduated from college relative to participants with pain.

Table 1.

Demographic data for each sample of pain patients, all pain patients combined, and all non-pain patients combined

| Participants with pain | Participants without pain |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Samples 1 and 2 Combined |

||

| Agea | 50.78 (10.81) | 54.06 (11.78) | 52.40 (11.37) | 51.56 (12.46) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 25.0% | 17.4% | 21.1% | 24.5% |

| Female | 75.0% | 82.6% | 78.9% | 75.5% |

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 2.0% |

| Asian | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.6% | 1.0% |

| Caucasian | 96.0% | 96.7% | 96.3% | 96.1% |

| Hispanic | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 2.0% |

| Native American | 1.6% | 2.5% | 2.0% | 0.0% |

| Pacific Islander | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| Receiving disability b | 52.4% | 52.9% | 52.8% | 40.2% |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 60.5% | 57.9% | 58.9% | 62.7% |

| Separated | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.7% | 1.0% |

| Divorced | 16.9% | 19.8% | 18.7% | 16.7% |

| Living with partner | 8.1% | 4.1% | 6.1% | 4.9% |

| Never married | 8.1% | 7.4% | 7.7% | 8.8% |

| Widow | 2.4% | 7.4% | 4.9% | 5.9% |

| Education | ||||

| Less than 12 years | 1.6% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| High school diploma or GED |

10.5% | 9.1% | 9.8% | 11.8% |

| Vocational or technical college |

5.6% | 8.3% | 6.9% | 4.9% |

| Some college | 29.0% | 23.1% | 26.0% | 19.6% |

| College graduate b | 29.8% | 38.8% | 34.1% | 47.1% |

| Graduate school | 23.4% | 19.8% | 22.0% | 16.7% |

Statistically significant difference between two groups with pain, p < .05

Statistically significant difference between combined group with pain and group without pain, p < .05

The means and standard deviation for pain interference at each pain intensity rating for both average and worst pain are reported in Table 2 and displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Mean pain interference for each level of average and worst pain intensity

| Pain interference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average pain | Worst pain | |||

| Pain intensity | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N |

| 0 | 1.33 (2.67) | 4 | 1.33 (2.67) | 4 |

| 1 | 1.30 (1.41) | 18 | 1.15 (1.09) | 13 |

| 2 | 1.56 (1.55) | 31 | 1.88 (1.85) | 21 |

| 3 | 2.48 (2.08) | 40 | 1.56 (1.45) | 23 |

| 4 | 3.05 (1.73) | 30 | 2.30 (1.83) | 17 |

| 5 | 3.46 (1.80) | 33 | 2.78 (1.86) | 26 |

| 6 | 5.10 (1.85) | 26 | 3.72 (1.91) | 22 |

| 7 | 4.82 (1.99) | 20 | 3.96 (1.98) | 37 |

| 8 | 5.46 (2.40) | 23 | 4.76 (2.33) | 33 |

| 9 | 5.06 (2.49) | 8 | 4.69 (2.28) | 25 |

| 10 | 7.11 (3.22) | 3 | 5.91 (2.60) | 15 |

Assessment of the classification schemes revealed that the optimal scheme for average pain intensity differs from the optimal scheme for worst pain intensity in our sample. As shown in Table 3, the optimal classification scheme (highest F value) for “average pain” was CP 2,5 (0-2, 3-5, 6-10). In this scheme 22.5% (N = 53), 43.6% (N = 103), and 33.9% (N = 80) of the participants were categorized as having mild, moderate, and severe average pain. Alternatively, the optimal classification scheme for “worst pain” was CP 4,7 (0-4, 5-7, 8-10), with 52% (N = 123), 33.5% (N = 79) and 14.4% (N = 34) participants classified as having mild, moderate, and severe.

Table 3.

Comparison of classification systems for mild, moderate and severe pain intensity based on interference with activity

| Pain type | CP 3,6 | CP 3,7 | CP 4,6 | CP 4,7 | CP 2,5 | CP 3,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 50.69 | 48.75 | 49.80 | 49.77 | 64.16 | |

| Worst | 46.11 | 46.52 | 46.66 | 49.00 | 46.68 |

Note. Values in table are F scores. All scores were p < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of the present study were to identify the optimal cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe pain among persons with MS, with secondary aims of assessing whether the optimal cutoffs varied based on whether the pain rating was for “average” or “worst pain”, and comparing the optimal cutoffs for persons with MS to those identified for persons with other medical conditions.

Results of the present study revealed two different classification schemes for “average” and “worst” pain. When asked to rate average pain over the past week, the optimal classification scheme was mild pain = 0-2, moderate pain = 3-5, and severe pain = 6-10, whereas when asked to rate worst pain over the past week, the optimal classification scheme was mild pain = 0-4, moderate pain = 5-7, and severe pain = 8-10. While these cutpoints represent the best classification schemes from our analyses, it is notable that the “best” scheme for average pain was more definitive, with a more distinct nonlinear association of pain intensity and pain interference, whereas the difference was less clear for worst pain; thus, we recommend interpreting our worst pain findings with more caution.

These findings for persons with MS indicate interesting similarities and differences relative to the findings of previous studies of pain cutoffs in non-MS populations. Importantly, the present results were consistent with all of the previous studies in the identification of a non-linear association between average pain intensity and pain interference (7-16). Among the eight previous studies that used “average pain” as the basis for analyses, five studies identified CP 3,6 as the optimal scheme (7, 11, 12, 14, 16), one study identified CP 4,6 as the optimal scheme (10), and two study identified CP 4,7 as the optimal scheme (9, 15); thus, our finding of CP 2,5 was one point lower on the 0-10 scale than the most commonly identified scheme. In constrast, our identification of CP 4,7 as the optimal scheme for “worst pain” was the same as one other study (14) and similar to the CP 4,6 scheme identified in three other studies (8, 9, 13) and the CP 3,7 scheme from one study (16). It has previously been suggested that average pain should be used for patients with consistent pain over time, whereas worst pain should be used for pain with greater variability (7, 11, 17); MS pain does not typically include extreme variability, as evidenced by modest differences between average and worst pain ratings (23).

Before considering reasons why persons with MS might differ from other populations in pain classification scheme, it is important to recognize that the differences in classification could be due to characteristics of the sample, and not the disease. Similar to many of the previous studies with the lowest classification schemes (CP 3,6) (7, 12, 14), our sample was a community sample and not necessarily patients who were actively seeking treatment for pain. This contrasts to other studies of clinical outpatients (9, 13, 15), patients on disability claims (10), and post-surgical inpatients (8) that had higher cutpoints. Thus, it is possible that pain begins to impact functioning at lower levels of intensity in individuals in the community who experience lower average levels of severity or chronicity relative to individuals with more experience with pain (i.e., pain chronicity) with higher pain levels.

Beyond recruitment sample, there is also the potential for differences between studies in demographics that could influence results, although one study assessing a community sample’s subjective categorization of pain ratings found no significant differences across many demographic variables (24). Thus, it is not known at this point if sample demographics contribute to differences in cutpoints. It remains possible that at least some of the differences we identified could be related to MS-specific causes.

Persons with MS and pain commonly experience pain in more than one location, with the average person reporting pain in 6.6 distinct sites (2, 23). Previous studies of non-MS populations have suggested that the number of pain sites, referred to as pain extent, is associated with pain interference and psychological suffering (25). Therefore, one might hypothesize that one of the reasons pain cutoffs are lower among persons with MS is that at least some of the pain interference could be attributed to pain extent, and not solely to pain intensity; future research should examine this possibility.

Another unique aspect of MS that makes the current sample distinct from other pain populations examining cutoffs is that it is a progressive demyelinating condition which typically results in multiple neurologic symptoms. There is some support for an association of pain and pain interference with disease progression and/or severity (2, 19, 26, 27), which suggests it may be the case that the greater interference attributed to pain may be related instead to disease progression. This could be due to a more limited ability for coping with pain in the context of an existing disease in which the individual must often manage a number of symptoms such as fatigue, sensory changes, physical impairment, bowel/bladder disruptions, mood disturbances, and cognitive changes. It could also reflect a difficulty differentiating pain-related interference from interference due to non-pain aspects of MS.

Ultimately, the use of cutoffs is intended to guide clinical decision-making. In previous studies, authors have questioned the value of identifying one point differences in cutpoints between conditions, as there is a certain value to having uniform cutpoints across conditions that would allow clinicians to easily identify when a patient’s level of pain warrants intervention (12). This has been particularly true when the optimal classification scheme differs only slightly from the most common classification scheme (12). Had we only analyzed the four commonly assessed schemes (CP 3,6; CP 3,7; CP 4,6; CP 4,7), we likely would have offered this same rationale, as those four classification schemes did not differ significantly in our sample. However, we identified a substantially different classification scheme, which lends more support to utilizing condition-specific cutpoints in the clinical setting. At minimum, clinicians are encouraged to use a lower threshold for determining that a patient with MS is experiencing clinically significant pain relative to patients with other medical conditions. Future research is needed on this topic, particularly to replicate findings of between-condition differences.

Additionally, the use of “average” and “worst” pain as the reference for cutoffs deserves careful consideration from a treatment perspective. As noted by Paul and colleagues (9), it is important to use the cutpoints that most closely match the goal of pain treatment. If clinicians are attempting to impact overall daily pain (and not just reduce how severe the pain gets at its worst), it appears most appropriate to use the average pain cutpoints to guide intervention. Alternatively, if the goal is to reduce the severity of worst pain (also known as breakthrough pain), then the worst pain cutpoints would be most appropriate. Given our identification of a two-point difference in cutpoints for average and worst pain, treatment decisions could differ significantly depending on which classification scheme is used.

There are important limitations in the present study that should be considered. Most notably, participants were recruited from a community sample, which may or may not differ from a clinical sample, as indicated above. Additionally, given that the present sample is a convenience sample of willing research participants, we believe that replication studies are needed to ensure that these findings are generalizable. Given that pain classification schemes are ultimately most useful for guiding clinical treatment decision-making, it would be interesting to determine whether these same findings hold among a sample of patients with MS specifically presenting for pain treatment. Additionally, as noted by Paul and colleagues (9), there might be differences in cutoffs as a function of culture, particularly in comparison to the international sample utilized by Serlin and colleagues (13). We also recognize that persons with MS and pain suffer from pain that varies in type and location. In future studies, we would recommend controlling for pain type, extent, and location, to determine whether these important factors contribute to pain interference beyond that which is already accounted for by pain intensity.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the study’s limitations, the findings make an important contribution to the literature by furthering our ability to use empirically-based cutoffs to inform the use of clinical guidelines for pain treatment as well as our understanding of the factors that might impact the cutoffs that are most appropriate for specific pain populations. The results of the present study also add to the existing literature by drawing similarities to studies of other populations but also by highlighting that clear, between-condition differences may exist that warrant using lower cutoffs for patients with MS relative to other medical conditions.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This research was supported by grant number P01 HD33988 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research). It was also supported in part by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant number MB 0008.

Footnotes

Financial relationships: Mark P. Jensen has received research support and/or consulting fees from RTI Health Solutions, Covidien, Endo Phamaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Schwartz Biosciences, Analgesic Research, Depomed, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Medtronic, and Smith & Nephew within the past 36 months. Kevin N. Alschuler and Dawn M. Ehde declare no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Chwastiak L, Bombardier CH, Sullivan MD, Kraft GH. Chronic pain in a large community sample of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9(6):605–11. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms939oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehde DM, Osborne TL, Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Kraft GH. The scope and nature of pain in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12(5):629–38. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD. Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain. 1999;83(2):157–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH . Cancer pain relief. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization WH . Cancer pain relief and palliative care; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacox A, Carr D, Payne R. Management of cancer pain. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1994. Clinical Practice guideline No. 9. AHCPR Pub. No. 90-0592. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen MP, Smith DG, Ehde DM, Robinsin LR. Pain site and the effects of amputation pain: further clarification of the meaning of mild, moderate, and severe pain. Pain. 2001;91(3):317–22. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, Hubbard R, Snabes M, Palmer SN, et al. Lessons learned from a multiple-dose post-operative analgesic trial. Pain. 2004;109(1-2):103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul SM, Zelman DC, Smith M, Miaskowski C. Categorizing the severity of cancer pain: further exploration of the establishment of cutpoints. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner JA, Franklin G, Heagerty PJ, Wu R, Egan K, Fulton-Kehoe D, et al. The association between pain and disability. Pain. 2004;112(3):307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelman DC, Dukes E, Brandenburg N, Bostrom A, Gore M. Identification of cut-points for mild, moderate and severe pain due to diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2005;115(1-2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanley MA, Masedo A, Jensen MP, Cardenas D, Turner JA. Pain interference in persons with spinal cord injury: classification of mild, moderate, and severe pain. J Pain. 2006;7(2):129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61(2):277–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00178-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fejer R, Jordan A, Hartvigsen J. Categorising the severity of neck pain: establishment of cut-points for use in clinical and epidemiological research. Pain. 2005;119(1-3):176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li KK, Harris K, Hadi S, Chow E. What should be the optimal cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain? J Palliat Med. 2007;10(6):1338–46. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Rintala DH, Anderson KO. Categorizing pain in patients seen in a Veterans Health Administration hospital: pain as the fifth vital sign. Psychological Services. 2008;5(3):239–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KO. Role of cutpoints: why grade pain intensity? Pain. 2005;113(1-2):5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kratz AL, Molton IR, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Nielson WR. Further evaluation of the motivational model of pain self-management: coping with chronic pain in multiple sclerosis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;41(3):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborne TL, Raichle KA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Kraft G. The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(3):217–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen MP, Karoly P. Self-report scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. 3rd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17(2):197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archibald CJ, McGrath PJ, Ritvo PG, Fisk JD, Bhan V, Maxner CE, et al. Pain prevalence, severity and impact in a clinic sample of multiple sclerosis patients. Pain. 1994;58(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Mobley GM, Cantor SB, Cleeland CS. Asking the community about cutpoints used to describe mild, moderate, and severe pain. J Pain. 2006;7(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Margolis RB. Pain extent: relations with psychological state, pain severity, pain history, and disability. Pain. 1990;41(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90006-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenager E, Knudsen L, Jensen K. Acute and chronic pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis. A 5-year follow-up study. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1995;16(9):629–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02230913. Epub 1995/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osborne TL, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Hanley MA, Kraft G. Psychosocial factors associated with pain intensity, pain-related interference, and psychological functioning in persons with multiple sclerosis and pain. Pain. 2007;127(1-2):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]