Abstract

Molecular understanding of placental functions and pregnancy disorders is limited by the absence of methods for placenta-specific gene manipulation. Although persistent placenta-specific gene expression has been achieved by lentivirus-based gene delivery methods, developmentally and physiologically important placental genes have highly stage-specific functions, requiring controllable, transient expression systems for functional analysis. Here, we describe an inducible, placenta-specific gene expression system that enables high-level, transient transgene expression and monitoring of gene expression by live bioluminescence imaging in mouse placenta at different stages of pregnancy. We used the third generation tetracycline-responsive tranactivator protein Tet-On 3G, with 10- to 100-fold increased sensitivity to doxycycline (Dox) compared with previous versions, enabling unusually sensitive on-off control of gene expression in vivo. Transgenic mice expressing Tet-On 3G were created using a new integrase-based, site-specific approach, yielding high-level transgene expression driven by a ubiquitous promoter. Blastocysts from these mice were transduced with the Tet-On 3G-response element promoter-driving firefly luciferase using lentivirus-mediated placenta-specific gene delivery and transferred into wild-type pseudopregnant recipients for placenta-specific, Dox-inducible gene expression. Systemic Dox administration at various time points during pregnancy led to transient, placenta-specific firefly luciferase expression as early as d 5 of pregnancy in a Dox dose-dependent manner. This system enables, for the first time, reliable pregnancy stage-specific induction of gene expression in the placenta and live monitoring of gene expression during pregnancy. It will be widely applicable to studies of both placental development and pregnancy, and the site-specific Tet-On G3 mouse will be valuable for studies in a broad range of tissues.

Placental dysfunction underlies numerous human pregnancy disorders that can threaten the health of both mothers and fetuses (1, 2). However, studies on the molecular basis of placental development and human pregnancy disorders have been constrained by a lack of appropriate methods for gene manipulation in the placenta (2, 3). The recent development of trophoblast lineage-specific gene expression methods based on lentiviral gene transduction in blastocysts by our laboratory and others has enabled persistent placenta-specific gene expression beginning at the blastocyst stage and is highly promising for placenta-specific gene manipulation (4–7). However, placental development and function are highly dynamic throughout pregnancy, and many key regulators are pregnancy stage specific, and currently no method is available to manipulate gene functions in the placenta at discrete stages of pregnancy (2, 3, 8).

Among the various approaches for conditional tissue-specific gene targeting (9–12), the Cre/lox P recombination system is among the most widely used for understanding of the roles of candidate genes in the pathophysiology of various organs. Moreover, a recent study has demonstrated the feasibility of placenta-specific gene knockins and knockouts through adaptation of lentivirus-mediated, trophoblast-specific transduction methods to transiently express Cre recombinase (13). However, these methods remain limited in their ability to analyze gene functions at discrete stages of pregnancy and placental development, because neither one allows selective on-off control of expression. The tetracycline-inducible Tet-On/Tet-Off system has been used with success for reversible and dose-dependent induction and repression of genes in specific time windows in both cultured cells and whole organisms, and numerous transgenic mice have been generated for ubiquitous or tissue-specific expression of the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) (Tet-Off protein) and reverse tTA (Tet-On protein) (12, 14–16). Also, several approaches have been developed to effectively circumvent the basal transgene leakiness in the absence of doxycycline (Dox), a disadvantage of the system (16–18). However, this system has never been tested in the placenta.

In this study, we describe an inducible placenta-specific gene expression system based on the third (latest) generation tetracycline-responsive transcriptional activator protein Tet-On 3G (also known as reverse tTA-V10) and an improved cognate promoter, Teg-On 3G-response element promoter (TRE3G) (19) (CLONTECH, Mountain View, CA). The advantages of the Tet-On 3G system over previous versions are dramatically increased sensitivity (10- to 100-fold) to Dox, improving the ability to precisely control gene expression in vivo and reducing potential Dox toxicity known to occur in pregnancy (20, 21) and a lack of detectable background leakiness (18). We created transgenic mice constitutively expressing Tet-On 3G using a novel integrase-based site-specific approach, recently developed by our group, which yields high-level marker expression from transgenes driven by a ubiquitous promoter (22). Blastocysts from these mice were transduced by lentiviral delivery of transgenes under the control of the tetracycline-responsive TRE3G promoter and transferred into wild-type pseudopregnant recipients for placenta-specific Dox-inducible gene expression.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care protocol and the institutional guidelines of the Veterinary Service Center at Stanford University. Zygotes of FVB H11P3 homozygous transgenic mice (Stanford Transgenic Research Facility) (22) were used for microinjection to produce Tet-On 3G transgenic mice. CD1 (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) females were mated with same strain vasectomized males to induce pseudopregnancy and used as embryo recipients for placenta-specific transgene expression studies (5). The day of detection of vaginal plugs was considered d 1 of pseudopregnancy (5, 23).

Recombinant DNA and lentiviral vector production

We used standard methods of recombinant DNA construction to generate all plasmids used in this study (5, 22). To produce attB-Tet-On 3G cassettes, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequence in pBT378, in which GFP is downstream of the pCA promoter (24, 25) and the pCA-GFP fusion gene is flanked by attB sites (attB-pCA-GFP-pA-attB), was replaced with the Tet-On 3G coding sequence from the pCMV-Tet-On 3G plasmid (CLONTECH). Briefly, the Tet-On 3G coding sequence was amplified with the following primers: forward 5′-TTTTGATATCCGCCACCATGTCTAGACTGGACAA-3′, with an EcoRV restriction site; and reverse 5′-TTTTGAATTCTTACCCGGGGAGCATGTCAAGGTC-3′, with an EcoRI restriction site, and digested with EcoRV and EcoRI. The pBT378 backbone was released by ClaI and EcoRI to remove the pCA-GFP cassette, and the pCA promoter was release by ClaI and SmaI. The pattB-Tet-On 3G plasmid was constructed by simultaneously ligating the pBT378 backbone, pCA promoter, and Tet-On 3G coding sequence together (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Then the plasmid was amplified and purified for micronuclear injection following our previously described method (22).

The lenti-TRE-firefly luciferase (Fluc) vector (pLV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP) (Supplemental Fig. 1) was constructed by replacing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1α-copGFP (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) with the TRE3G-Luciferase cassette from pTRE3G-Luc plasmid (CLONTECH). Then, the HIV-1-based, self-inactivating lentivirus was generated from pLV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP using the standard calcium phosphate method as described previously (5). Virus titers (particles per milliliter) were determined using the QuickTiter Lentivirus Quantitation kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA) (5).

Generation of transgenic animals

All procedures associated with the generation of pCA-Tet-On 3G site-specific transformants are identical to those used previously, including methods for micronuclear injection, generation of capped φC31 mRNA (22). Briefly, capped mRNA encoding a codon-optimized φC31 integrase (26) was generated with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Foster City, CA), and the plasmid DNA (pattB-Tet-On 3G) was prepared using a modified QIAGEN miniprep procedure according to the manufacturer's instructions and our previously described method (22). Microinjection was performed with an established setup at the Stanford Transgenic Research Facility (22). Superovulated homozygous attP-containing FVB H11P3 transgenic females were bred to FVB H11P3 males to generate homozygous attP-containing zygotes. The DNA/mRNA mix (3 ng/μl of pattB-Tet-On 3G plasmid and 48 ng/μl of in vitro-transcribed φC31 integrase mRNA) was microinjected into a single pronucleus and cytoplasm of each of the approximately 200 zygotes using a continuous flow injection mode (22). Out of the total injected embryos, 70 (35%) cleaved to produce two-cell embryos after overnight culture and were implanted into the oviducts of six pseudopregnant CD1 recipients. Forty-two pups were born, and tail biopsies were screened for site-specific integration of the transgene by PCR as described below.

Polymerase chain reaction

Three different primer pairs were used for detection of site-specific integration of the transgene (Fig. 1A) in tail biopsies of F0 animals using the Phire Animal Tissue Direct PCR kit (Finnzymes, Vantaa, Finland): PCR1 (5′-end junction), forward 5′-ggtgataggtggcaagtggtattc-3′ and reverse 5′-atcaactaccgccacctcgac-3′; PCR2 (3′-end junction), forward 5′-cgatgtaggtcacggtctcg-3′ and reverse 5′-gtgggactgctttttccaga-3′; and PCR3 (internal to Tet-On 3G), forward 5′-actctgctctggaattactc-3′ and reverse 5′-gtttcgtactgtttctctgttg-3′. Three F0 pups exhibited the correct PCR products and were used as founders for breeding.

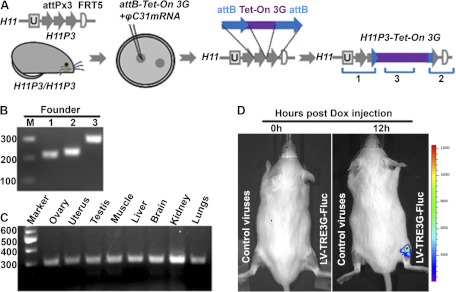

Fig. 1.

Generation of transgenic mice ubiquitously expressing Tet-On 3G protein. A, Strategy for Tet-On 3G transgenic mouse production. Zygotes from H11P3 FVB mice were used for microinjection of the pattB-Tet-On 3G plasmid and φC31 integrase mRNA. Recombination can occur between the two attB sites in the transgene cassette and two of the three attP target sequences, leading to site-specific insertion of the transgene (22). B, PCR genotyping of tail biopsies. Site-specific integration was detected by amplification of the unique 5′ and 3′ junctions predicted by integration at H11P3 (1 and 2 in A), as well as amplification of a sequence internal to the Tet-On 3G cassette (3 in A). C, RT-PCR results showing Tet-On 3G expression in a broad array of tissues from the Tet-On 3G transgenic mice. D, Functional test of Tet-On 3G inducibility in hindleg muscle in Tet-On 3G transgenic mice. Dox was administered to animals (ip) 72 h after LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP injection into the hindleg muscles and imaged at different times after Dox administration by live BLI. Specific luciferase signal was detected only in the hindlegs injected with lentivirus containing the TRE3G-Fluc cassette.

Mouse breeding and transgene expression

The male F0 Tet-On 3G site-specific transgenic FVB mice and their progenies were outcrossed to CD1 females up to four generations following a standard protocol (22), and the fourth generation outcrossed mice (CD1F4) were crossed to each other to make homozygous mice. The mice at each generation were genotyped by the three primer pairs described above, and RT-PCR was used to detect Tet-On 3G expression in different tissues with the following primers: forward 5′-actctgctctggaattactc-3′ and reverse 5′-gtttcgtactgtttctctgttg-3′ (27).

Dox induction of transgene expression and live bioluminescence imaging (BLI)

The experimental details, including viral transduction and imaging of blastocysts, embryo transfer, and live BLI, have been published previously (5) and are presented in the Supplemental data. Briefly, individual blastocysts from Tet-On 3G transgenic females were transduced with LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP virus after removal of zona pellucidae and incubated with an optimal dose of Dox (50 ng/ml). BLI of blastocysts was performed using the Xenogen In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS 200; Caliper Life Sciences, Mountain View, CA).

For Dox-induced placenta-specific gene expression studies, blastocysts with maximum photon fluxes in the range of 2.0E+4–6.0E+4 photons per second per centimeter squared per steradian (p/sec/cm2/sr) were transferred to CD1 pseudopregnant recipients. The animals were injected (ip) with an optimal dose of Dox (1 mg/kg) at different days of pregnancy, and Fluc expression in the placenta was examined by BLI using the IVIS 200.

Results and discussion

In our initial efforts to establish inducible placenta-specific gene expression with the Tet-On 3G system, we used lentiviral gene transduction to express the Tet-On 3G transactivator protein and introduce genes of interest under the control of the TRE3G promoter through simultaneous transfection of blastocysts with two different lentivirus vectors using our previously developed trophoblast-specific gene delivery method (data not shown). Unfortunately, this system produced only low-level and uneven Dox-induced gene expression in the placenta and did not work to our satisfaction. We then created a new transgenic mouse ubiquitously expressing Tet-On 3G through site-specific integration. Blastocysts from these mice were transfected with the LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP virus and transferred into pseudopregnant females. Administration of Dox to these pregnant animals led to transient Fluc expression in the placenta in discrete time windows and the ability to monitor placental Fluc expression by live BLI.

Generation of Tet-On 3G transgenic mice by site-specific recombination

To develop a Dox-inducible gene expression system for the mouse placenta in vivo, mice constitutively expressing the Tet-On 3G transactivator protein were generated by a newly developed integrase-mediated method for site-specific transgenesis via pronuclear microinjection (22), as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). The previously generated transgenic mouse line H11P3 (22), in which three shortened tandem φC31 integrase attP sites (attPx3) were inserted into the intergenic Hipp11 (H11) locus on mouse chromosome 11, was used to obtain donor zygotes. Double recombination between the two attB sequences and two of the three attP sequences in H11 allows insertion of only the transgene, without flanking vector sequences; the absence of the bacterial plasmid backbone has been shown to result in more consistent high-level transgene expression from a ubiquitous promoter (22). After pronuclear injection of the Tet-On 3G construct (Fig. 1A) and transfer of embryos, 42 pups were born, and screening for site-specific integration of the transgene by the PCR scheme outlined in Materials and Methods and Fig. 1 identified three transgenic pups. Pups from subsequent breeding expressed Tet-On 3G mRNA expression in all tissues examined (Fig. 1C), suggesting ubiquitous expression.

As a proof of principle and to test the functionality of the expressed Tet-On 3G protein, we injected lentivirus containing the TRE3G promoter-Fluc fusion gene and GFP under the control of a constitutive promoter (LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP) into the hindleg muscle of Tet-On 3G mice (Fig. 1D). Injection of Dox (ip) induced strong Fluc signal at the sites of injection of the virus in a dose-dependent manner but not in any other tissues or in the hindleg muscle without Dox injection. These results suggest that the signal is highly specific to Dox induction. Furthermore, there was no detectable background signal, as observed in earlier generations of Tet-On system (28).

Transient Dox-induced transgene expression in blastocysts

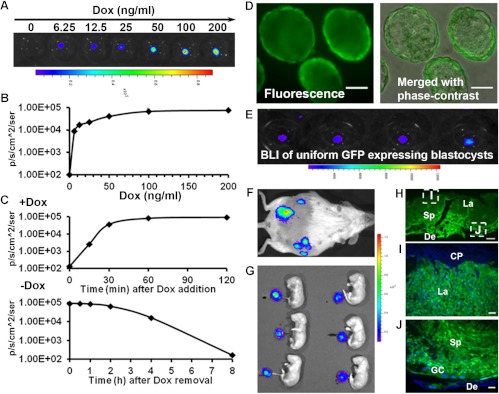

In our previous work, we showed that preselection of blastocysts based on the transfection efficiency of the lentivirus is essential for uniform, high-level expression of transgenes in the resulting placentas (5). Here, we demonstrate the feasibility of preselecting lentivirally transfected blastocysts on the basis of Dox-induced reporter gene expression before transfer into pseudopregnant mice, as discussed further below. Fluc expression in lentivirus-transfected blastocysts (using LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP) from Tet-On 3G mice was measured after incubation with various doses of Dox. The signal intensity was strongly dose dependent, reaching a response maximum at approximately 100 ng/ml (Fig. 2B). The signal could be detected as early as 15 min after Dox exposure, even at the lowest dose (6.25 ng/ml), and maximal signal intensity was achieved by approximately 30 min (Fig. 2, A–C). Fluc signal also decayed rapidly, becoming undetectable by 8 h after Dox removal (Fig. 2C). Transfer of these blastocysts to pseudopregnant recipients did not affect the rate of implantation and pregnancy (Supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting no adverse effect of Dox induction or the selection process. Alternatively, our viral construct permits selection of blastocysts based on GFP expression in the trophectoderm, which we found to correlate with the level of Fluc induction (Fig. 2, D and E). The quick induction and decay of Dox-induced signal in the blastocysts suggest the potential, for the first time, to study the role of gene functions in preimplantation stage blastocysts (trophectoderm) in embryo development and placentation.

Fig. 2.

Dox-induced transgene expression in blastocysts and preselection of blastocysts for uniform Dox-induced placenta-specific gene expression among placentas of the same litter. A and B, Dose dependence of Fluc expression measured by BLI in blastocysts, imaged 1 h after Dox exposure at various doses. An optimal concentration of Dox (50 ng/ml) was determined from the dose-response curve (B). C, Time course of bioluminescence signal after addition (+Dox, 50 ng/ml) and removal (−Dox) of Dox. d and E, Preselection of blastocysts for embryo transfer based on uniform and high-level GFP expression (D) and confirmation of Dox-induced high-level Fluc expression in preselected blastocysts (E). F and G, Live BLI of Dox-induced placenta-specific Fluc expression on d 18 of pregnancy (F) after transfer with preselected blastocysts. Imaging of the placentas and fetuses reveals nearly uniform Fluc expression among all placentas, and signal was specific to placentas and not detectable in fetuses (G). H–J, GFP expression in different trophoblast lineages in placental sections from d 18 of pregnancy. H, Full-thickness section. I, Labyrinth layer (La). J, Spongiotrophoblast (Sp) and giant cell (GC) layers. CP, Chorionic plate; De, decidua. Scale bars, 50 μm (D, I, and J) and 500 μm (H).

Placenta-specific Dox-induced transgene expression

To determine the specificity of Dox-induced transgene expression in the placenta, we transferred transfected (LV-TRE3G-Fluc-EF1α-copGFP) blastocysts from Tet-On 3G mice into pseudopregnant CD1 dams. Consistent with our previous study (5), preselection of virally transduced blastocysts resulted in uniform, high-level Dox-induced gene expression in all placentas of the same litter, and GFP expression in placental sections revealed transgene expression in all trophoblast lineages (Fig. 2, G–J). Few focal areas showed GFP-positive cells in the decidua, but colocalization studies revealed that all GFP-positive cells in the decidua were also immunopositive for CK8 (Supplemental Fig. 3C), suggesting that the signal in the decidua is from the invading trophoblasts, not from maternal decidual cells.

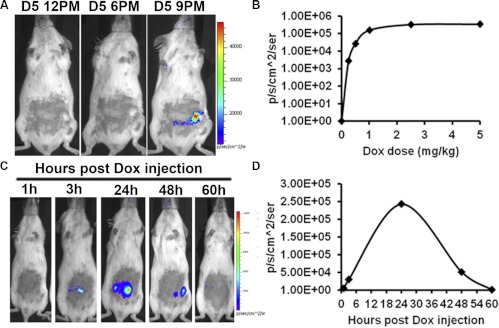

We first compared administration of Dox through drinking water and through ip injection by monitoring Fluc expression in live animals. Similar to earlier reports in other tissues (29, 30), both methods produced strong Fluc signals in placentas without any detectable signal in other tissues or in the placentas before Dox administration. However, ip injection produced a faster and stronger response (earliest detection at 3 h after administration, vs. 6 h for drinking water) (data not shown) and was used for all subsequent experiments. We next compared the responses to different doses of ip-injected Dox at early, mid, and late pregnancy by BLI (Fig. 3B). At all three stages of pregnancy, the dose-response relationship was similar, with the luminescence signal in the placenta reaching a plateau at approximately 1 mg Dox/kg body weight. Using this dose (1 mg/kg) with maximal response, we then determined the time course of induction and decay after a single ip injection (Fig. 3D). We first detected Fluc signal over the uterine area at 3 h after injection. The signal reached a peak at 24 h and decayed to an undetectable level by 60 h (Fig. 3C), suggesting that transgene expression can be precisely regulated in the placenta within a 60-h time window of pregnancy in a Dox dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 3.

Optimization of Dox-induced placenta-specific transgene expression. A, BLI of Fluc expression on d 4–6 of pregnancy after Dox injection on d 4 and 5. The signal could be detected as early as d 5 (2100 h) of pregnancy. B, Inducible Fluc expression after different doses of Dox injection on d 8 of pregnancy and imaged on d 9. Nearly maximum Fluc expression was induced at approximately 1 mg/kg of Dox. C and D, The kinetic changes in the induced Fluc expression after a single injection of Dox (1 mg/kg) on d 6 of pregnancy. Note that peak Fluc expression was reached 24 h after Dox injection, and the signal was not detectable at 60 h.

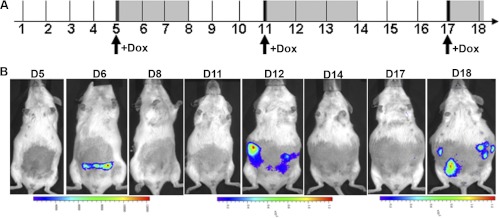

To fully characterize the capabilities of this system for turning gene expression on and off throughout pregnancy, we performed serial inductions with Dox within single pregnancies and monitored the expression responses by BLI. Beginning with the earliest practical induction at the blastocyst stage (d 5) (Fig. 3A), we induced Fluc expression serially in three discrete time windows by Dox injections at d 5, 11, and 17 of pregnancy, corresponding to early, mid, and late pregnancy (Fig. 4A). After each induction, the Fluc signal reached a peak at approximately 1 d and was not detectable after 2 d. Although we did not observe any adverse effect on pregnancy with any of the doses of Dox used in this study, earlier reports indicated adverse effects of very high doses of tetracycline use during pregnancy (21). It may be noted that, if required, the dose of Dox can be further reduced in our system (Fig. 3B), emphasizing a particular advantage of the use of the highly Dox-sensitive Tet-On 3G system in pregnancy.

Fig. 4.

Dox-induced transgene expression in multiple time windows within a single pregnancy. Fluc expression was induced in three discrete time windows by Dox injections (single dose) at d 5, 11, and 17 of pregnancy (A). Live BLI was performed every 24 h after Dox administration (B).

In sum, we have presented a system that enables transient, inducible, and high-level expression of transgenes in the placenta at all stages of pregnancy in mice, providing effective control of both the timing and duration of expression in the trophectoderm lineage. It will likely enable a wide range of studies on molecular functions in placental development, function, and disease, including studies of preimplantation functions and placental effects on fetal development. Moreover, it uses the greatly improved Tet-On transactivator-promoter system, virtually eliminating Dox-independent gene activation and permitting greater control of gene activation through increased sensitivity, a critical requirement for studies of highly dynamic tissues, like the placenta.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant1R21HD068981 (to N.R.N.), Lucile Packard Foundation for Children's Health (X.F.), the NIH Grant R01EB009689 (to J.C.W.), the Children's Health Initiative at Stanford (N.R.N.), the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (N.R.N.), and the Preeclampsia Foundation (N.R.N.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BLI

- Bioluminescence imaging

- CMV<

- cytomegalovirus

- Dox

- doxycycline

- Fluc

- firefly luciferase

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- tTA

- tetracycline transactivator.

References

- 1. Acharya G, Albrecht C, Benton SJ, Cotechini T, Dechend R, Dilworth MR, Duttaroy AK, Grotmol T, Heazell AE, Jansson T, Johnstone ED, Jones HN, Jones RL, Lager S, Laine K, Nagirnaja L, Nystad M, Powell T, Redman C, Sadovsky Y, Sibley C, Troisi R, Wadsack C, Westwood M, Lash GE. 2012 IFPA Meeting 2011. Workshop report I: placenta: predicting future health; roles of lipids in the growth and development of feto-placental unit; placental nutrient sensing; placental research to solve clinical problems—a translational approach. Placenta 33(Suppl):S4–S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossant J, Cross JC. 2001. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat Rev Genet 2:538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Renaud SJ, Karim Rumi MA, Soares MJ. 2011. Review: genetic manipulation of the rodent placenta. Placenta 32(Suppl 2):S130–S135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okada Y, Ueshin Y, Isotani A, Saito-Fujita T, Nakashima H, Kimura K, Mizoguchi A, Oh-Hora M, Mori Y, Ogata M, Oshima RG, Okabe M, Ikawa M. 2007. Complementation of placental defects and embryonic lethality by trophoblast-specific lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Biotechnol 25:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fan X, Ren P, Dhal S, Bejerano G, Goodman SB, Druzin ML, Gambhir SS, Nayak NR. 2011. Noninvasive monitoring of placenta-specific transgene expression by bioluminescence imaging. PLoS One 6:e16348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Georgiades P, Cox B, Gertsenstein M, Chawengsaksophak K, Rossant J. 2007. Trophoblast-specific gene manipulation using lentivirus-based vectors. Biotechniques 42:317–318, 320: 322–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee DS, Rumi MA, Konno T, Soares MJ. 2009. In vivo genetic manipulation of the rat trophoblast cell lineage using lentiviral vector delivery. Genesis 47:433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gheorghe C, Mohan S, Longo LD. 2006. Gene expression patterns in the developing murine placenta. J Soc Gynecol Investig 13:256–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewandoski M. 2001. Conditional control of gene expression in the mouse. Nat Rev Genet 2:743–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryding AD, Sharp MG, Mullins JJ. 2001. Conditional transgenic technologies. J Endocrinol 171:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gossen M, Bujard H. 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:5547–5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Müller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. 1995. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science 268:1766–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morioka Y, Isotani A, Oshima RG, Okabe M, Ikawa M. 2009. Placenta-specific gene activation and inactivation using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors with the Cre/LoxP system. Genesis 47:793–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu K, Deng XY, Yue Y, Guo ZM, Huang B, Hong X, Xiao D, Chen XG. 2005. Generation of the regulatory protein rtTA transgenic mice. World J Gastroenterol 11:2885–2891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furth PA, St Onge L, Böger H, Gruss P, Gossen M, Kistner A, Bujard H, Hennighausen L. 1994. Temporal control of gene expression in transgenic mice by a tetracycline-responsive promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:9302–9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu Z, Zheng T, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Elias JA. 2002. Tetracycline-controlled transcriptional regulation systems: advances and application in transgenic animal modeling. Semin Cell Dev Biol 13:121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu Z, Ma B, Homer RJ, Zheng T, Elias JA. 2001. Use of the tetracycline-controlled transcriptional silencer (tTS) to eliminate transgene leak in inducible overexpression transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 276:25222–25229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loew R, Heinz N, Hampf M, Bujard H, Gossen M. 2010. Improved Tet-responsive promoters with minimized background expression. BMC Biotechnol 10:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou X, Vink M, Klaver B, Berkhout B, Das AT. 2006. Optimization of the Tet-On system for regulated gene expression through viral evolution. Gene Ther 13:1382–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwarz RH. 1981. Considerations of antibiotic therapy during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 58:95S–99S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moutier R, Tchang F, Caucheteux SM, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C. 2003. Placental anomalies and fetal loss in mice, after administration of doxycycline in food for tet-system activation. Transgenic Res 12:369–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tasic B, Hippenmeyer S, Wang C, Gamboa M, Zong H, Chen-Tsai Y, Luo L. 2011. Site-specific integrase-mediated transgenesis in mice via pronuclear injection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:7902–7907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fan X, Krieg S, Kuo CJ, Wiegand SJ, Rabinovitch M, Druzin ML, Brenner RM, Giudice LC, Nayak NR. 2008. VEGF blockade inhibits angiogenesis and reepithelialization of endometrium. FASEB J 22:3571–3580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. 2005. Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell 121:479–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raymond CS, Soriano P. 2007. High-efficiency FLP and PhiC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS One 2:e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheng Y, Lin CC, Yue J, Sukhwani M, Shuttleworth JJ, Chu T, Orwig KE. 2010. Generation and characterization of a Tet-On (rtTA-M2) transgenic rat. BMC Dev Biol 10:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perl AK, Tichelaar JW, Whitsett JA. 2002. Conditional gene expression in the respiratory epithelium of the mouse. Transgenic Res 11:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu P, Aller MI, Baron U, Cambridge S, Bausen M, Herb J, Sawinski J, Cetin A, Osten P, Nelson ML, Kügler S, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R, Hasan MT. 2007. Silencing and un-silencing of tetracycline-controlled genes in neurons. PLoS One 2:e533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vanrell L, Di Scala M, Blanco L, Otano I, Gil-Farina I, Baldim V, Paneda A, Berraondo P, Beattie SG, Chtarto A, Tenenbaum L, Prieto J, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G. 2011. Development of a liver-specific Tet-On inducible system for AAV vectors and its application in the treatment of liver cancer. Mol Ther 19:1245–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.