Abstract

The peripheral chemoreflex is known to be enhanced in individuals with hypertension. In pre-hypertensive (PH) and adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) carotid body type I (glomus) cells exhibit hypersensitivity to chemosensory stimuli and elevated sympathoexcitatory responses to peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation. Herein, we eliminated carotid body inputs in both PH-SHRs and SHRs to test the hypothesis that heightened peripheral chemoreceptor activity contributes to both the development and maintenance of hypertension. The carotid sinus nerves were surgically denervated under general anaesthesia in 4- and 12-week-old SHRs. Control groups comprised sham-operated SHRs and aged-matched sham-operated and carotid sinus nerve denervated Wistar rats. Arterial blood pressure was recorded chronically in conscious, freely moving animals. Successful carotid sinus nerve denervation (CSD) was confirmed by testing respiratory responses to hypoxia (10% O2) or cardiovascular responses to i.v. injection of sodium cyanide. In the SHR, CSD reduced both the development of hypertension and its maintenance (P < 0.05) and was associated with a reduction in sympathetic vasomotor tone (as revealed by frequency domain analysis and reduced arterial pressure responses to administration of hexamethonium; P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated SHR) and an improvement in baroreflex sensitivity. No effect on blood pressure was observed in sham-operated SHRs or Wistar rats. In conclusion, carotid sinus nerve inputs from the carotid body are, in part, responsible for elevated sympathetic tone and critical for the genesis of hypertension in the developing SHR and its maintenance in later life.

Key points

Peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity is enhanced in hypertension yet the role of these receptors in the development and maintenance of high blood pressure remains unknown.

Carotid chemoreceptors were denervated in both young and adult spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) by sectioning the carotid sinus nerves bilaterally while recording arterial blood pressure chronically using radio telemetry.

Carotid sinus denervation (CSD) in the young animals prevented arterial pressure from reaching the hypertensive levels observed in sham-operated animals whereas in adult SHRs arterial pressure fell by ∼20 mmHg.

After CSD there was a decrease in sympathetic activity, measured indirectly using power spectral analysis and hexamethonium, and an improvement in baroreceptor reflex gain.

Carotid bodies are active in the SHR and contribute to both the development and maintenance of hypertension; whether carotid body ablation is a useful anti-hypertensive intervention in drug-resistant hypertensive patients remains to be resolved.

Introduction

Essential hypertension is an important risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease, stroke and renal failure. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms underlying the aetiology of essential hypertension is imperative in order to reduce its potential clinical, social and economic consequences. Studies conducted in both animal models of hypertension and hypertensive patients revealed increased vasoconstrictor sympathetic tone, which may contribute to both the development and maintenance of hypertension (Anderson et al. 1989; Esler et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2004a,b). However, the mechanisms leading to increased sympathetic vasomotor tone in neurogenic hypertension remain unclear.

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) plays a crucial role in the regulation of circulation and blood pressure (Fisher & Paton, 2011; Zubcevic et al. 2011). Sympathetic vasomotor and cardiac neural activities are produced by the sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the spinal cord that receive tonic excitatory drive from pre-sympathetic networks within the brainstem and the hypothalamus (Dampney, 1994; Guyenet et al. 1996; Dampney et al. 2003; Madden & Sved, 2003; Marina et al. 2011). Many factors are known to affect sympathetic tone, including circulating hormones, blood osmolality, Na+ levels and cardiorespiratory afferent inputs, one being from the peripheral chemoreceptors. In the rat the carotid body (CB) is the main peripheral chemoreceptor site located at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. Hypoxia and hypercapnia are detected by the CB type I cells, resulting in hyperventilation, sympathoexcitation and increases in arterial pressure (Prabhkar & Semenza 2012). The role of the CB in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease has gained considerable interest. There is evidence that sympathoexcitation in sleep apnoea and heart failure may result from enhanced activity of the CB chemoreceptors (Chua et al. 1996; Sun et al. 1999a,b). Chemoreflex-evoked sympathetic activity responses are enhanced in human patients and animal models of systemic hypertension (Przybylski et al. 1982; Trzebski et al. 1982; Somers et al. 1988; Trzebski, 1992). However, the hypothesis that CB chemoreceptor drive plays an important role in the pathogenesis and/or maintenance of high arterial pressure remains undetermined. Here, we sectioned carotid sinus nerves bilaterally in both pre-hypertensive-SHRs (PH-SHRs) and adult SHRs to determine the effect of carotid sinus denervation (CSD) and hence elimination of CB inputs on both the development and maintenance of hypertension. Some of the results of this study have been reported in abstract form (Abdala et al. 2011a,b).

Methods

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and associated guidelines. Juvenile (4 weeks; n = 12) and adult (12 weeks; n = 15) SHRs and Wistar rats (n = 12) bred in the University of Bristol Animal Services Unit were used.

Carotid sinus denervation (CSD)

Rats were anaesthetised with ketamine (60 mg kg−1; i.m.) and medetomidine (250 μg kg−1, i.m.). Using strict aseptic techniques, an anterior midline neck incision was performed and the sternohyoid and sternocleidomastoid muscles were carefully retracted. The carotid bifurcation was exposed, the occipital artery was retracted, the CB visualised and the carotid sinus nerve and its branches sectioned. Sham-operated rats underwent the same surgical procedures to expose the CB but the carotid sinus nerves were left intact. On sectioning the second sinus nerve each rat showed a transient apnoea, with some requiring resuscitation. No mortalities occurred, suggesting that there were no lethal apnoeic episodes post CSD (see Supplemental Fig. S1); animals gained weight normally. To assess the completeness of CSD respiratory responses to systemic hypoxia (10% O2 in the inspired gas mixture for ∼1 min) were measured by either whole-body plethysmography (custom-made device) or arterial pressure and heart rate responses recorded after i.v. injection of sodium cyanide (NaCN, 100 μl of 0.04%) 3–4 weeks post CSD.

Arterial pressure measurements and manipulation

(i) PH-SHRs. Six weeks after CSD (i.e. at 10 weeks of age) rats were anaesthetised with halothane (3% in O2) and a polyethylene tube (0.6 mm OD, 0.3 mm ID; PE-10, Beckton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) was inserted in the left femoral artery so that its tip was in the abdominal aorta caudal to the renal arteries (Abdala et al. 2006) and tunnelled subcutaneously and exteriorized between the scapulae. The catheter was filled with sterile saline containing heparin (50 U ml−1) and penicillin G (2000 U ml−1), and sealed with a plastic cap. All animals received an intramuscular injection of penicillin G (24,000 IU) and streptomycin (10 mg). Catheters were flushed twice weekly with the same solution containing heparin and penicillin. Arterial pressure recordings were performed 1 and 3 weeks after arterial catheterization, i.e. at 11 and 13 weeks of age, respectively. On the day of the experiments, the catheter was connected to a pressure transducer (Gould). Arterial pressure measurements were taken continuously for 1 h once the animal was resting or sleeping. The signal was recorded using a 1401 data acquisition system and Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) and digitized at 5 kHz.

(2) In adult rats, radio-telemeters were implanted in the abdomen and their catheters inserted into the aorta as described before (Waki et al. 2006). One week of recovery was permitted; arterial pressure was recorded for 5 days prior to, and 3 weeks after, CSD. Arterial pressure was recorded for 5 min every hour, 24 h per day using Hey Presto software (Waki et al. 2006), and heart rate and respiratory rate derived from the arterial pressure waveform (see below for details). Unless otherwise stated, the data shown for arterial pressures and ventilatory frequency represent daily averages of these 5 min periods. During CSD surgery, a polyurethane catheter (0.033 in (∼0.84 mm) OD; 0.014 in (∼0.36 mm) ID; Micro-Renathane, Braintree Scientific) was advanced into the jugular vein so the tip was placed into the right atrium. The catheter tip was coated with a heparin complex (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, USA). The catheter was tunnelled subcutaneously and connected to a custom-built stainless-steel connector (23G) exteriorised between the scapulas, as described previously (Abdala et al. 2006). The catheter was filled with saline containing heparin (100 U ml−1) and penicillin G (2000 U ml−1) solution. Indwelling catheters were flushed with the latter solution once a week. All animals received an intramuscular injection of penicillin G (24,000 IU) and streptomycin (10 mg). Solutions of phenylephrine (0.1 mg ml−1) and sodium nitroprusside (0.1 mg ml−1) were infused i.v. to obtain 1–2 mmHg s−1 changes in arterial pressure between ∼60–180 mmHg. These data were then used to generate (5-parameter sigmoidal regression) baroreflex function curves.

Power spectral analysis

For catheter-measured arterial pressure, spectral analysis of the systolic pressure variability was performed off-line to estimate the relative level of sympathetic activity in rats at 13 weeks of age. For each 5 min recording period, the beat-to-beat pulse frequencies and systolic pressures were converted into data points every 100 ms using a spline interpolation. The resulting time series were divided into half-overlapping sequential sets of 512 data points. For each data set, after the linear trend was removed and Hanning window applied, power spectral density was computed using the FFT algorithm (Spike 7.08, Cambridge Electronic Design). The following frequencies were calculated in normalized units: <0.27 Hz (very low frequency; VLF), 0.27–0.75 Hz (low frequency; LF) and 0.75–3.3 Hz (high frequency; HF). The ratio of the LF component to the HF component was used as an indicator of sympatho-parasympathetic balance. Respiratory rate was inferred from the peaks of respiratory modulation of systolic pressure frequency spectrum. For radio-telemetered arterial pressure, Hey Presto software (Waki et al. 2006) was employed to perform spectral analysis of systolic pressure and heart rate using the same parameters as described above. Because of controversies surrounding LF as a marker of vasomotor sympathetic tone, we also administered hexamethonium (10 mg kg−1 i.v.) to block ganglionic transmission to directly assess the relative level of sympathetic tone as revealed by the magnitude of the fall in arterial pressure.

Data analysis

Data sets (10 min) were used for analysis of systolic, diastolic, mean pulse pressures, heart rate and respiratory rate. Heart rate was derived from inter-pulse intervals. Values are presented as mean ± SEM except where stated. Data were compared by two-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test. Differences between groups with P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

CSD and the genesis of hypertension in developing SHR

Arterial pressure response

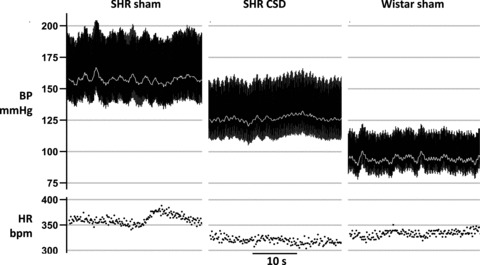

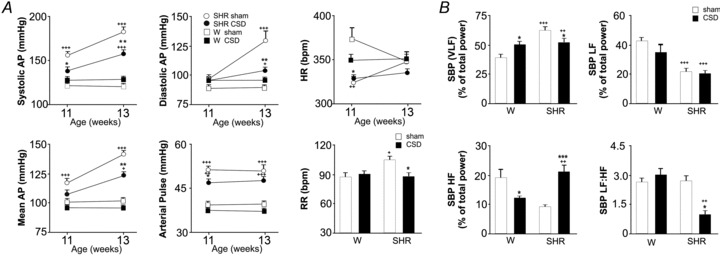

Figure 1 shows a representative arterial pressure recording from a 13-week-old CSD SHR, sham-operated SHR and sham-operated Wistar rat. CSD conducted at a pre-hypertensive age delayed the development and reduced the degree of hypertension later in life (Figs 1 and 2A). At 11 weeks of age pulse, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure were all elevated significantly in sham-operated SHR (n = 6) compared with CSD SHRs (n = 6) and sham-operated Wistar rats (n = 6, P < 0.001). CSD SHRs remained normotensive at 11 weeks of age (P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated SHR; Fig. 2A). By 13 weeks of age, CSD SHRs developed hypertension (n = 6, P < 0.05 vs. CSD Wistar rats, n = 6); however, their pulse systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure were all significantly lower compared with sham-operated SHRs (P < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Arterial blood pressure was not affected by CSD in Wistar rats. There were no significant differences in pulse, systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure, heart rate and respiratory rate between CSD and sham-operated Wistar rats (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1. CSD is anti-hypertensive in the developing spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR).

Representative recordings of the arterial blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) in 13-week-old CSD SHR, sham-operated SHR and sham-operated Wistar rat. Carotid sinus nerves were denervated at 4 weeks of age before SHRs become hypertensive.

Figure 2. Anti-hypertensive effect of CSD in the pre-hypertensive (PH)-SHRs is associated with lowered sympathetic vasomotor tone.

A, CSD in PH-SHRs delays the development and reduces the magnitude of hypertension. Following CSD at 4 weeks of age, SHRs remained normotensive at 11 weeks old while sham-operated SHRs developed hypertension. By 13 weeks of age, CSD SHRs were hypertensive (P < 0.05 vs. Wistar rats) but systolic, diastolic, mean and pulse pressures were all lower compared with those in sham-operated SHRs. There was no effect of CSD on heart rate (HR) but respiratory rate (RR) was reduced in the PH-SHR to a level comparable to normotensive rats. B, in PH-SHRs, sympathetic vasomotor tone was reduced as revealed by a reduction in very low frequency (VLF) and LF:HF ratio of systolic pressure (P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated SHR). The low frequency (LF) component in SHR was not affected by the CSD. In contrast, CSD Wistar rats showed higher power of the VLF component (vs. sham-operated Wistar rats) and lower power in the HF component (vs. sham-operated Wistar rats), whilst the LF component and LF:HF ratio were unaffected. Data represent mean ± SEM. Effect of CSD within each strain (n = 6 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01) and between strains (+P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001) were analysed with two-way ANOVA.

Heart rate changes

Both sham-operated and CSD SHRs showed significantly lower heart rates compared with sham-operated and CSD Wistar rats at 11 weeks of age (P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). At 13 weeks of age no differences in heart rate were observed between groups.

Spectral analysis

(i) Systolic pressure: CSD Wistar rats showed higher power of the systolic pressure VLF component (P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated Wistar) and lower power in the HF component (P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated Wistar), whilst the LF component and LF:HF ratio were unaffected (Fig. 2B). In contrast, CSD SHRs displayed an increase in the HF component (P < 0.001 vs. sham-operated SHR) and a reduction in both the VLF component and the LF:HF ratio of systolic BP (P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated SHR; Fig. 2B). The LF component in the SHR was not affected by CSD. (ii) Heart rate variability: There were no significant differences in the VLF, LF, HF and LF:HF between sham-operated and CSD SHRs. (iii) Respiratory frequency was higher in sham-operated SHR vs. sham-operated Wistar rats and CSD reduced breathing rate in SHRs (P < 0.05) to that of the Wistar rats (Fig. 2A).

CSD and maintenance of hypertension in the adult SHR

We next evaluated the effect of CSD on arterial pressure and sympathetic tone in adult SHR.

Arterial pressure and heart rate responses

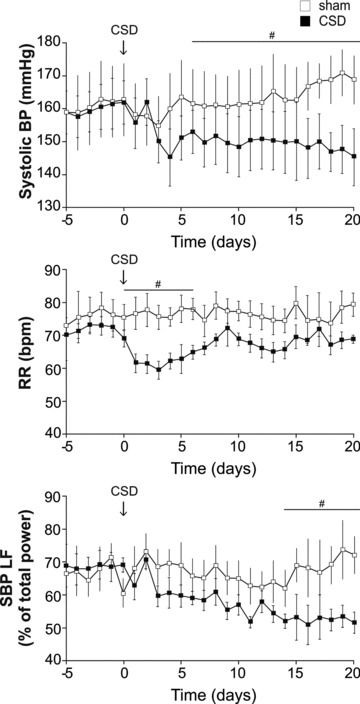

Figure 3 shows the time course of systolic pressure response following CSD. Systolic pressure decreased over 5–10 days to reach a plateau of −17 ± 3 mmHg (n = 10, P < 0.05). Mean arterial and diastolic pressures fell by –15 ± 2 (P < 0.05) and –17 ± 2 (P < 0.05) mmHg, respectively. Lowered arterial pressure was maintained with no sign of recovery for at least 3 weeks (and 6 weeks in 3 additional CSD SHRs). There was a trend of an increase in systolic pressure in sham-operated SHRs (from 161 ± 7 to 173 ± 6 mmHg; Fig. 3; NS), reflecting a continuation of the age-dependent arterial pressure elevation in this strain, which was not observed in the CSD SHR. No changes in heart rate in either CSD or sham-operated SHRs was observed. Circadian analysis revealed that the CSD-evoked fall in arterial pressure was consistent across the day–night cycle (–16 ± 7 and –18 ± 7 mmHg, respectively). Moreover, after a disruption in the days immediately following surgery, a normal circadian day–night variation was re-established 5–7 days after CSD in SBP (3 ± 1 mmHg, 2 ± 1 mmHg, baseline vs. CSD) and heart rate (33 ± 5 beats min−1, 38 ± 7 beats min−1, baseline vs. CSD).

Figure 3. In established hypertension, CSD in SHRs reduces arterial pressure, respiratory rate and the power of low frequency systolic pressure variability.

Time profile of changes in systolic pressure (BP), respiratory rate (RR, breaths min−1) and low-frequency SBP variability (an indirect index of vasomotor tone) 5 days before and 21 days after CSD (arrows; n = 8) or sham surgery (n = 7) in the adult (12 week old) SHR. #P < 0.05.

Spectral analysis

(i) Systolic pressure: Low power frequency of systolic pressure showed a time-dependent decrease that followed the time course of the depressor response after CSD (Fig. 3; P < 0.05); other spectra were not altered by CSD. No spectral changes were observed in the sham-operated animals. (ii) Heart rate: No changes in spectral frequencies associated with heart rate were observed in either SHR groups. (iii) Respiratory rate showed a transient decrease lasting 6 days after CSD (from 71 ± 2 to 57 ± 3 breaths min−1; Fig. 3, P < 0.01), which then recovered to control levels.

Sympathetic vasomotor tone

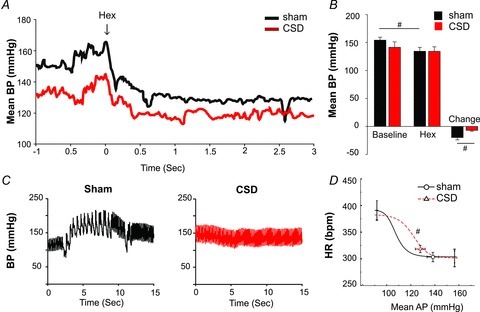

Hexamethonium (10 mg kg−1) produced a smaller fall in arterial pressure in CSD SHRs compared with sham-operated SHRs (–7 ± 2 mmHg vs.–20 ± 4 mmHg; Fig. 4A and B; n = 4 per group, P < 0.05) suggesting that the basal level of sympathetic vasomotor tone had been lowered by CSD.

Figure 4. CSD in the adult SHR reduces sympathetic vasomotor tone and improves baroreceptor reflex sensitivity.

A and B, blockade of autonomic ganglionic transmission produced a larger fall in arterial pressure in sham-operated SHR compared with that in the CSD SHR suggesting less vasomotor sympathetic tone in the latter group. C, arterial blood pressure (BP) responses during sodium cyanide injection (i.v.) to activate the peripheral chemoreceptors. Note that after CSD, there was no peripheral chemoreflex-mediated pressor and bradycardic responses (compared with sham-operated) indicative of an efficacious denervation. D, baroreflex function curve of heart rate (HR) vs. mean blood pressure (MBP) obtained using i.v. phenylephrine and sodium nitroprusside injections. Note the shift in the operating point to re-engage reflex function after CSD (red) compared with sham-operated (black). #P < 0.05.

Baroreflex testing

In the adult SHR, CSD rats exhibited a right shift in the cardiac baroreflex curve compared with sham, predominantly due to an increase in the BP50 curve parameter reflecting the midpoint of the curve (Fig. 4C and D; 107 ± 7 mmHg in Sham, 122 ± 4 mmHg in CSD P < 0.05). In combination with the observed reduction in the arterial pressure, this places the operating point of the cardiac baroreflex into the linear part of the baroreflex function curve, compared with Sham rats in which the operating point lies on the lower plateau.

Assessing the efficacy of CSD

Using whole-body plethysmography, effective peripheral chemodenervation was confirmed 24 h after the surgery in PH-SHRs using ∼1 min exposure to 10% hypoxia. Respiratory activity was unperturbed by exposing CSD SHRs and Wistar rats to hypoxia whereas sham-operated animals displayed robust increases in both respiratory frequency and amplitude (n = 4; Supplemental Fig. S2). In the adult SHR, i.v. bolus injections of sodium cyanide evoked a rapid and transient bradycardia (–86 ± 31 beats min−1) and a pressor response (45 ± 10 mmHg) in sham-operated animals; these responses were significantly attenuated in the CSD animals (–13 ± 5 beats min−1, 4 ± 1 mmHg; n = 4 per group, P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our results obtained in the present study demonstrate that CSD either in PH-SHRs or adult SHRs with established hypertension reduces arterial pressure by almost 20 mmHg. CSD had an anti-hypertensive effect that was associated with a reduction of sympathetic vasomotor tone, as deduced from both spectral analysis of systolic pressure and changes in arterial pressure following ganglionic blockade.

The peripheral chemoreceptor reflex response has been shown to be significantly enhanced in patients with primary hypertension (Trzebski et al. 1982; Tafil-Klawe et al. 1985; Izdebska et al. 1998; Sinski et al. 2011) and SHRs (Tan et al. 2010). Enhanced CB activity was suggested to result in alterations in the respiratory–sympathetic coupling and increased muscle vasoconstrictor activity which may contribute to the development of hypertension (Przybylski et al. 1982; Trzebski et al. 1982; Somers et al. 1988; Trzebski, 1992; Zoccal et al. 2008; Simms et al. 2009; Sinski et al. 2011). In addition, morphological studies have revealed that CBs are enlarged in hypertensive patients (Heath et al. 1985). These latter results, and the data reported herein, demonstrate a fundamental role of the CB input in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension.

CSD SHRs remained normotensive for up to 11 weeks of age, a time when sham-operated SHRs had already developed significant hypertension. Subsequently, SHRs with CSD developed markedly attenuated hypertension at 13 weeks of age. This delay in the onset of hypertension in the absence of the carotid sinus nerve input suggests that enhanced peripheral chemoreceptor activity contributes to the ontogeny of hypertension. Sham-operated SHRs (performed in either juvenile or adult SHRs) also showed a higher respiratory rate compared with CSD SHRs. Thus, the enhanced peripheral chemoreceptor activity in the SHR augments both respiration and sympathetic activity. However, in contrast to the blood pressure lowering effect, the reduced ventilatory rate we observed after CSD was not sustained, which is consistent with that reported recently (Mouradian et al. 2012). Clinically, acute silencing of the CB activity by hyperoxia decreases muscle vasoconstrictor activity in hypertensive subjects (Przybylski et al. 1982; Izdebska et al. 1998; Sinski et al. 2011), which demonstrates a role for CB inputs in the control of baseline sympathetic tone in essential hypertension.

We noted a significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure that was greater than systolic blood pressure between 11 and 13 weeks in the SHR. There are numerous possibilities to explain this: (i) Between 11 and 13 weeks the CB become more active in SHRs and that this activity is destined towards driving sympathetic vasomotor tone preferentially, hence diastolic pressure decreases in absence of CB. This is feasible since sympathetic activity to heart and arterioles can be controlled differentially; (ii) CB sensitisation between 11 and 13 weeks may reflect the damaging effects of high sympathetic drive supplying the arterioles in the CB at this time (i.e. stiffening, media wall thickening, decrease lumen wall diameter) thereby reducing blood flow to the CB; (iii) By 11–13 weeks of age the persistent high sympathetic activity in the intact SHR initiates end organ damage to systemic blood vessels causing proportionately greater increases in diastolic pressure; (iv) There may also be maturational differences in neuro-muscular transmission optimizing the efficacy of sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction around 13 weeks of age.

Reduced hypertension in the CSD PH-SHR was associated with a significant decrease in the LF:HF ratio and the VLF of systolic pressure. In adult SHRs CSD reduced LF systolic pressure variability. These data indicate reduced sympathetic vasomotor tone, albeit indirectly. Ganglionic blockade was used to further assess the relative level of autonomic tone in the adult SHR, and these results support a reduction in vasomotor sympathetic activity following CSD. The changes in HF systolic pressure variability in the developing SHR may reflect altered respiratory–sympathetic coupling secondary to an altered pattern of breathing, consistent with the changes in respiratory frequency we report herein. Surprisingly, there were no detectable changes in heart rate spectra in either maturing or adult SHRs suggesting that the fall in arterial pressure observed is not dependent on an alteration in autonomic drive to the heart and that CSD does not appear to affect parasympathetic tone. This might seem surprising given that the peripheral chemoreflex response includes a powerful vagal bradycardia dependent on the degree of lung inflation. We suggest that the absence of changes in cardiac autonomic spectra reflect compensation from other cardiorespiratory reflex inputs including aortic chemoreceptors (Brophy et al. 1999; Piskuric et al. 2011).

We acknowledge that CSD will eliminate carotid sinus baroreceptors as well as carotid body sensory input to the brainstem. However, the aortic baroreceptors remained intact. The loss of carotid baroreflex inputs might be expected to drive pressure up not down, as we have seen. The baroreceptor reflex in the SHR is known to be impaired, in particular through a reduced vagal capacity to control HR (Head & Adams, 1988). To our surprise, CSD also provided an improvement in baroreflex function, presumably that of aortic origin. We found that the operating point moved up the reflex function curve back onto its linear component. This is mechanistically important, as the baroreflex can now function to buffer the variability in arterial pressure thereby reducing end organ damage. This result reflects the known reciprocating antagonism on sympathetic activity between the peripheral chemo- and baro-reflexes (Paton et al. 2005). A further possibility is that the sensitised baroreceptor reflex post CSD contributes to the anti-hypertensive effect and/or maintains the lower level of arterial blood pressure.

The mechanism underlying heightened CB chemoreceptor activation during the development and maintenance of hypertension remains elusive. In juvenile SHRs, type I cells display enhanced sensitivity to low pH due to increased expression of two acid-sensing non-voltage-gated channels ASIC3 and TASK1 (Tan et al. 2010), although the balance between carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulphide within the CB as well as the relative activity of HIF1αvs. HIF2α all play a role (Prabhkar & Semenza, 2012). Animal models of chronic heart failure have revealed that CB chemoreceptor activity is augmented by angiotensin II receptors (Schultz, 2011), impaired nitric oxide synthase activity (Sun et al. 1999b), reduced CB blood flow (Ding et al. 2011), enhanced adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (Wyatt et al. 2008) and inflammation (Lam et al. 2011). Heightened sympathetic drive to the arterioles of the CB itself may also contribute to its hyperactivity due to hypoperfusion (via vasoconstriction and vascular remodelling) and inflammation.

In conclusion, our study shows that in the SHR, the CB input plays a fundamental role in both the genesis and maintenance of hypertension, and the associated increases in sympathetic vasomotor tone. By extension, and assuming there are no deleterious side effects, CB denervation may prove to be effective in lowering arterial pressure in conditions of drug-resistant hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the British Heart Foundation (J.F.R.P., N.M.), The Wellcome Trust (A.V.G.) and a gift from Coridea NC1 to J.F.R.P. A.V.G. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. N.M. is a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Science Research Fellow. We thank Ana M. A. Alviar Baquero and Shahed B. Sheikh for their technical assistance during data acquisition.

Glossary

- ABP

arterial blood pressure

- CB

carotid body

- HF

high frequency

- HR

heart rate

- LF

low frequency

- PH

pre-hypertensive

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- VLF

very low frequency

Author contributions

A.P.A., A.V.G. and J.F.R.P. conceived the experiments. A.P.A., F.D.M., A.V.G. and J.F.R.P. designed the experiments. A.P.A., F.D.M. and E.B.H. collected, analysed and interpreted the data. A.P.A., F.D.M., N.M., J.F.R.P. and A.V.G. drafted the article. A.P.A., F.D.M., Z.J.E., E.B.H., M.F., N.M., A.V.G., P.A.S. and J.F.R.P. revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved it before final submission as well as guiding its revision.

Supplementary material

Supplemental Figure 1

Supplemental Figure 2

References

- Abdala APL, Marina N, Gourine AV, Paton JFR. Peripheral chemoreceptor inputs contribute to the development of high blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Proc Physiol Soc. 2011a;23:PC22. [Google Scholar]

- Abdala APL, Paton JFR, Gourine AV. Peripheral chemoreceptor (PC) inputs contribute to the development of high blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) FASEB J. 2011b;25:640.10. [Google Scholar]

- Abdala AP, Schoorlemmer GH, Colombari E. Ablation of NK1 receptor bearing neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract blunts cardiovascular reflexes in awake rats. Brain Res. 2006;1119:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EA, Sinkey CA, Lawton WJ, Mark AL. Elevated sympathetic nerve activity in borderline hypertensive humans. Evidence from direct intraneural recordings. Hypertension. 1989;14:177–183. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy S, Ford TW, Carey M, Jones JF. Activity of aortic chemoreceptors in the anaesthetized rat. J Physiol. 1999;514:821–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.821ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua TP, Clark AL, Amadi AA, Coats AJ. Relation between chemosensitivity and the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:650–657. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Tagawa T, Fontes MA, Potts PD, Polson JW. Medullary and supramedullary mechanisms regulating sympathetic vasomotor tone. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:209–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Li YL, Schultz HD. Role of blood flow in carotid body chemoreflex function in heart failure. J Physiol. 2011;589:245–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler M, Rumantir M, Kaye D, Jennings G, Hastings J, Socratous F, Lambert G. Sympathetic nerve biology in essential hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:986–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JP, Paton JF. The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2011 doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.66. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.66. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Koshiya N, Huangfu D, Baraban SC, Stornetta RL, Li YW. Role of medulla oblongata in generation of sympathetic and vagal outflows. Prog Brain Res. 1996;107:127–144. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head GA, Adams MA. Time course of changes in baroreceptor reflex control of heart rate in conscious SHR and WKY: contribution of the cardiac vagus and sympathetic nerves. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1988;15(4):289–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1988.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath D, Smith P, Fitch R, Harris P. Comparative pathology of the enlarged carotid body. J Comp Pathol. 1985;95:259–271. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(85)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izdebska E, Cybulska I, Sawicki M, Izdebski J, Trzebski A. Postexercise decrease in arterial blood pressure, total peripheral resistance and in circulatory responses to brief hyperoxia in subjects with mild essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:855–860. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam SY, Liu Y, Ng KM, Lau CF, Liong EC, Tipoe GL, Fung ML. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces local inflammation of the rat carotid body via functional upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine pathways. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;137:303–317. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0900-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CJ, Sved AF. Cardiovascular regulation after destruction of the C1 cell group of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2734–H2748. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00155.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marina N, Abdala AP, Korsak A, Simms AE, Allen AM, Paton JF, Gourine AV. Control of sympathetic vasomotor tone by catecholaminergic C1 neurones of the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:703–710. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouradian GC, Forster HV, Hodges MR. Acute and chronic effects of carotid body denervation (CBD) on ventilation and chemoreflexes in three rat strains. J Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.234658. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JFR, Boscan P, Pickering AE, Nalivaiko E. The yin and yang of cardiac autonomic control: vago-sympathetic interactions revisited. Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskuric NA, Vollmer C, Nurse CA. Confocal immunofluorescence study of rat aortic body chemoreceptors and associated neurons in situ and in vitro. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:856–873. doi: 10.1002/cne.22553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Gaseous messengers in oxygen sensing. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski J, Trzebski A, Czyzewski T, Jodkowski J. Responses to hyperoxia, hypoxia, hypercapnia and almitrine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Bulletin Europeen de Physiopathologie Respiratoire - Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 1982;18:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz HD. Angiotensin and carotid body chemoreception in heart failure. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms AE, Paton JF, Pickering AE, Allen AM. Amplified respiratory-sympathetic coupling in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: does it contribute to hypertension? J Physiol. 2009;587:597–610. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinski M, Lewandowski J, Przybylski J, Bidiuk J, Abramczyk P, Ciarka A, Gaciong Z. Tonic activity of carotid body chemoreceptors contributes to the increased sympathetic drive in essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011 doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.209. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Graham LN, Mackintosh AF, Stoker JB, Mary DASG. Relationship between central sympathetic activity and stages of human hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004a;17:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Meaney JFM, Graham LN, Stoker JB, Mackintosh AF, Mary DASG, Ball SG. Relationship of neurovascular compression to central sympathetic discharge and essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004b;43:1453–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers VK, Mark AL, Abboud FM. Potentiation of sympathetic nerve responses to hypoxia in borderline hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1988;11:608–612. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Wang W, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Enhanced peripheral chemoreflex function in conscious rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 1999a;86:1264–1272. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Wang W, Zucker IH, Schultz HD. Enhanced activity of carotid body chemoreceptors in rabbits with heart failure: role of nitric oxide. J Appl Physiol. 1999b;86:1273–1282. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafil-Klawe M, Trzebski A, Klawe J, Palko T. Augmented chemoreceptor reflex tonic drive in early human hypertension and in normotensive subjects with family background of hypertension. Acta Physiol Pol. 1985;36:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan ZY, Lu Y, Whiteis CA, Simms AE, Paton JF, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM. Chemoreceptor hypersensitivity, sympathetic excitation, and overexpression of ASIC and TASK channels before the onset of hypertension in SHR. Circ Res. 2010;106:536–545. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzebski A. Arterial chemoreceptor reflex and hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;19:562–566. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzebski A, Tafil M, Zoltowski M, Przybylski J. Increased sensitivity of the arterial chemoreceptor drive in young men with mild hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 1982;16:163–172. doi: 10.1093/cvr/16.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waki H, Katahira K, Polson JW, Kasparov S, Murphy D, Paton JFR. Automation of analysis of cardiovascular autonomic function from chronic measurements of arterial pressure in conscious rats. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:201–213. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt CN, Pearson SA, Kumar P, Peers C, Hardie DG, Evans AM. Key roles for AMP-activated protein kinase in the function of the carotid body? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;605:63–68. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccal DB, Simms AE, Bonagamba LG, Braga VA, Pickering AE, Paton JF, Machado BH. Increased sympathetic outflow in juvenile rats submitted to chronic intermittent hypoxia correlates with enhanced expiratory activity. J Physiol. 2008;586:3253–3265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubcevic J, Waki H, Raizada MK, Paton JF. Autonomic-immune-vascular interaction: an emerging concept for neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:1026–1033. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.169748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.