Abstract

It has been suggested that shallow slopes of mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPPA)–cardiac output ( ) relationships and pulmonary transit of agitated contrast during exercise may be associated with a higher maximal aerobic capacity (

) relationships and pulmonary transit of agitated contrast during exercise may be associated with a higher maximal aerobic capacity ( ). If so, individuals with a higher

). If so, individuals with a higher  could also exhibit a higher pulmonary vascular distensibility and increased pulmonary capillary blood volume during exercise. Exercise stress echocardiography was performed with repetitive injections of agitated contrast and measurements of MPPA,

could also exhibit a higher pulmonary vascular distensibility and increased pulmonary capillary blood volume during exercise. Exercise stress echocardiography was performed with repetitive injections of agitated contrast and measurements of MPPA,  and lung diffusing capacities for carbon monoxide (DL,CO) and nitric oxide (DL,NO) in 24 healthy individuals. A pulmonary vascular distensibility coefficient α was mathematically determined from the slight natural curvilinearity of multipoint MPPA–

and lung diffusing capacities for carbon monoxide (DL,CO) and nitric oxide (DL,NO) in 24 healthy individuals. A pulmonary vascular distensibility coefficient α was mathematically determined from the slight natural curvilinearity of multipoint MPPA– plots. Membrane (Dm) and capillary blood volume (Vc) components of lung diffusing capacity were calculated. Maximal exercise increased MPPA, cardiac index (CI), DL,CO and DL,NO. The slope of the linear best fit of MPPA–CI was 3.2 ± 0.5 mmHg min l−1 m2 and α was 1.1 ± 0.3% mmHg−1. A multivariable analysis showed that higher α and greater Vc independently predicted

plots. Membrane (Dm) and capillary blood volume (Vc) components of lung diffusing capacity were calculated. Maximal exercise increased MPPA, cardiac index (CI), DL,CO and DL,NO. The slope of the linear best fit of MPPA–CI was 3.2 ± 0.5 mmHg min l−1 m2 and α was 1.1 ± 0.3% mmHg−1. A multivariable analysis showed that higher α and greater Vc independently predicted  . All individuals had markedly positive pulmonary transit of agitated contrast at maximal exercise, with increases proportional to increases in pulmonary capillary pressure and Vc. Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast was not related to pulse oximetry arterial oxygen saturation. Therefore, a more distensible pulmonary circulation and a greater pulmonary capillary blood volume are associated with a higher

. All individuals had markedly positive pulmonary transit of agitated contrast at maximal exercise, with increases proportional to increases in pulmonary capillary pressure and Vc. Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast was not related to pulse oximetry arterial oxygen saturation. Therefore, a more distensible pulmonary circulation and a greater pulmonary capillary blood volume are associated with a higher  in healthy individuals. Agitated contrast commonly transits through the pulmonary circulation at exercise, in proportion to increased pulmonary capillary pressures.

in healthy individuals. Agitated contrast commonly transits through the pulmonary circulation at exercise, in proportion to increased pulmonary capillary pressures.

Key points

Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast (PTAC) occurs during exercise in healthy individuals.

It has been suggested that positive PTAC reflects a greater pulmonary vascular reserve, allowing for the right ventricle to operate at a decreased afterload at high levels of exercise.

In this study, we determined whether individuals with highest maximal aerobic capacity have the greatest pulmonary vascular distensibility, highest PTAC and greatest increase in the capillary blood component of lung diffusing capacity during exercise.

We observed that individuals with highest maximal aerobic capacity have a more distensible pulmonary circulation as observed through greater pulmonary vascular distensibility, greater pulmonary capillary blood volume, and lowest pulmonary vascular resistance at maximal exercise.

Pulmonary vascular distensibility predicts aerobic capacity in healthy individuals.

Introduction

Intravenously injected agitated contrast does not normally transit through the pulmonary circulation at rest and is therefore useful for the diagnosis of cardiac right-to-left shunts, when contrast appears simultaneously in right and left heart chambers, (Cabanes et al. 2002) or pulmonary arterio-venous dilatation, when contrast appears in left heart chambers after four to five beats (Shovlin & Letarte, 1999; Rodriguez-Roisin & Krowka, 2008). However, it has recently been shown that pulmonary transit of agitated contrast (PTAC) occurs during exercise in healthy individuals (Eldridge et al. 2004; Stickland et al. 2004). Whether positive PTAC at exercise in healthy individuals is explained by pulmonary vascular distension or by the opening of parallel arterio-venous shunts remains uncertain (Hopkins et al. 2009b; Lovering et al. 2009). Positive PTAC is not associated with exercise-induced hypoxaemia (La Gerche et al. 2010), making true pulmonary shunting less likely than a diffusion/perfusion imbalance on pulmonary vascular distension (Naeije & Faoro, 2009). It has been suggested that positive PTAC reflects a greater pulmonary vascular reserve, allowing for the right ventricle to operate at a decreased afterload at high levels of exercise (La Gerche et al. 2010).

Pulmonary vascular response to exercise varies considerably from one individual to another, with slopes of mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPPA)–cardiac output ( ) relationships ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 in invasive (Reeves et al. 1989) and in echocardiographic studies (Argiento et al. 2010). Multipoint MPPA–

) relationships ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 in invasive (Reeves et al. 1989) and in echocardiographic studies (Argiento et al. 2010). Multipoint MPPA– relationships are actually slightly curvilinear, which is explained by the natural distensibility of the pulmonary circulation, and accounts for the variability in slopes of best linear fits (Reeves et al. 2005). The distensibility of the pulmonary vessels can be defined by a coefficient α calculated as percentage change in diameter per mmHg of pressure using a mathematical model of the pulmonary circulation (Linehan et al. 1992; Reeves et al. 2005; Argiento et al. 2010).

relationships are actually slightly curvilinear, which is explained by the natural distensibility of the pulmonary circulation, and accounts for the variability in slopes of best linear fits (Reeves et al. 2005). The distensibility of the pulmonary vessels can be defined by a coefficient α calculated as percentage change in diameter per mmHg of pressure using a mathematical model of the pulmonary circulation (Linehan et al. 1992; Reeves et al. 2005; Argiento et al. 2010).

The longitudinal distribution of resistances in the pulmonary circulation has been shown to be 60% pre-capillary and 40% capillaro-venous (Cope et al. 1992). Therefore, capillary resistance significantly contributes to changes in pulmonary vascular resistance during exercise. Capillary blood volume can be estimated from lung diffusing capacity measurements using both carbon monoxide (CO) and nitric oxide (NO) as tracer gases. The Roughton and Forster equation states that 1/DL,CO = 1/Dm+ 1/θVc where DL,CO is the diffusing capacity of the lung for CO, Dm its membrane component and Vc the capillary blood volume (Roughton & Forster, 1957). Since the reaction of NO with haemoglobin is quasi-instantaneous, it has been assumed that θNO is infinite so that the transfer factor for NO with correction for the NO/CO ratio of diffusivity allows for the calculation of Dm, and hence Vc (Guenard et al. 1987). A simple DL,NO/DL,CO ratio may identify relative changes in the component of lung diffusion, so that a thinning of the capillary sheet increases the ratio while a thickening of the blood sheet decreases the ratio (Glenet et al. 2007). In the present study, we hypothesized that individuals with the highest maximal aerobic capacity ( ) have the shallowest slopes of MPPA–

) have the shallowest slopes of MPPA– relationships, the greatest pulmonary vascular distensibility, the highest PTAC and the greatest increase in the capillary blood component of lung diffusing capacity during exercise.

relationships, the greatest pulmonary vascular distensibility, the highest PTAC and the greatest increase in the capillary blood component of lung diffusing capacity during exercise.

Methods

The study included 24 healthy individuals with no history of cardiovascular or respiratory abnormalities. Participants were recreationally active and performed on average 258 ± 172 min of exercise per week. The study conformed to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Erasme University Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants reported to the laboratory on two occasions. The first visit consisted of an incremental exercise test on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer (Ergoselect II 1200, Ergoline, Bitz, Germany) to determine  . Initial workload was set at 35 W and workload increased by 25 W for men and 20 W for women with each 1 min stage until volitional fatigue. Breath by breath data were collected and analysed every 5 s using a metabolic system (CPX, Medgraphics, St Paul, MN, USA) that was calibrated with room air and standardized gas. The slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production (

. Initial workload was set at 35 W and workload increased by 25 W for men and 20 W for women with each 1 min stage until volitional fatigue. Breath by breath data were collected and analysed every 5 s using a metabolic system (CPX, Medgraphics, St Paul, MN, USA) that was calibrated with room air and standardized gas. The slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production ( /

/ ) was calculated with values from rest to maximal exercise.

) was calculated with values from rest to maximal exercise.  was considered to be achieved when two of the following criteria were met: an increase in oxygen consumption of less than 100 ml min−1 with a further increase in workload, respiratory exchange ratio (RER) greater than 1.1 or achievement of age-predicted maximal heart rate (Table 1). To determine whether posture affects

was considered to be achieved when two of the following criteria were met: an increase in oxygen consumption of less than 100 ml min−1 with a further increase in workload, respiratory exchange ratio (RER) greater than 1.1 or achievement of age-predicted maximal heart rate (Table 1). To determine whether posture affects  , a subgroup of 12 participants performed the incremental exercise test in both upright and semi-recumbent positions, and no difference in

, a subgroup of 12 participants performed the incremental exercise test in both upright and semi-recumbent positions, and no difference in  was observed (43.8 ± 6.9 vs. 42.9 ± 7.0 ml kg−1 min−1, P = 0.27). The second visit consisted of a standard resting echocardiographic examination, resting spirometry measurements as well as an incremental exercise test in combination with echocardiographic, PTAC and lung diffusing capacity measurements. For this second incremental exercise test, initial workload was set at 0 W and workload increased by 20 W for both men and women with each 3 min stage until volitional fatigue. Pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (

was observed (43.8 ± 6.9 vs. 42.9 ± 7.0 ml kg−1 min−1, P = 0.27). The second visit consisted of a standard resting echocardiographic examination, resting spirometry measurements as well as an incremental exercise test in combination with echocardiographic, PTAC and lung diffusing capacity measurements. For this second incremental exercise test, initial workload was set at 0 W and workload increased by 20 W for both men and women with each 3 min stage until volitional fatigue. Pulse oximetry oxygen saturation ( ) was continuously monitored with a finger pulse oximeter (Nellcor Puritan Bennett Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA).

) was continuously monitored with a finger pulse oximeter (Nellcor Puritan Bennett Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA).

Table 1.

Participants' baseline characteristics and response to maximal exercise testing

| Female/male | 6/18 |

| Age (years) | 25 ± 6 |

| Height (cm) | 177 ± 7 |

| Weight (kg) | 71 ± 11 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 22.5 ± 2.3 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.87 ± 0.17 |

| Slow vital capacity (% predicted) | 100.4 ± 11.5 |

| Forced vital capacity (% predicted) | 110.4 ± 17.4 |

(ml kg−1 min−1) (ml kg−1 min−1) |

41.8 ± 7.1 |

| Maximal heart rate (bpm) | 179 ± 12 |

| Maximal RER | 1.28 ± 0.08 |

/ /

|

26.8 ± 3.6 |

: maximal aerobic capacity; RER: respiratory exchange ratio,

: maximal aerobic capacity; RER: respiratory exchange ratio,  /

/ : slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production.

: slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production.

Echocardiography

Doppler echocardiography measurements were continuously obtained with a portable ultrasound system (CX50 CompactXtreme Ultrasound System, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) during the incremental exercise test on a semi-recumbent cycle ergometer laterally tilted by 20 to 30 deg to the left. During each exercise stage, a repeating loop of measurements was obtained. Stroke volume was estimated from left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) cross sectional area measured at rest and pulsed Doppler time–velocity integral (TVI) measurements (Christie et al. 1987). Stroke volume was calculated with the following equation: Stroke volume = 3.14 × (LVOT diameter/2) × (LVOT diameter/2) × TVI, and  was calculated as the product of stroke volume and heart rate. Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure was estimated from a trans-tricuspid pressure gradient calculated from the maximum velocity of continuous Doppler tricuspid regurgitation (TRV) and corrected for right atrial pressure as Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure = 4 × TRV2+ 5 mmHg (Yock & Popp, 1984). Left atrial pressure was estimated from the ratio of Doppler mitral early (E) flow-velocity wave and tissue Doppler mitral annulus early (E′) velocity with the following equation: Left atrial pressure = 1.9 + 1.24E/E′ (Nagueh et al. 1997). MPPA was calculated as 0.6 × pulmonary arterial systolic pressure + 2 (Chemla et al. 2004). Pulmonary capillary pressure (Pcap) was calculated as 0.4 × (MPPA – left atrial pressure) + left atrial pressure (Cope et al. 1992).

was calculated as the product of stroke volume and heart rate. Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure was estimated from a trans-tricuspid pressure gradient calculated from the maximum velocity of continuous Doppler tricuspid regurgitation (TRV) and corrected for right atrial pressure as Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure = 4 × TRV2+ 5 mmHg (Yock & Popp, 1984). Left atrial pressure was estimated from the ratio of Doppler mitral early (E) flow-velocity wave and tissue Doppler mitral annulus early (E′) velocity with the following equation: Left atrial pressure = 1.9 + 1.24E/E′ (Nagueh et al. 1997). MPPA was calculated as 0.6 × pulmonary arterial systolic pressure + 2 (Chemla et al. 2004). Pulmonary capillary pressure (Pcap) was calculated as 0.4 × (MPPA – left atrial pressure) + left atrial pressure (Cope et al. 1992).  was indexed to body surface area (cardiac index, CI) (Du Bois & Du Bois, 1989).

was indexed to body surface area (cardiac index, CI) (Du Bois & Du Bois, 1989).

Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast

PTAC was determined by Doppler echocardiography following injection of an agitated contrast solution. A venous catheter with a saline solution lock was placed in an antecubital vein of the right arm. A contrast solution of succinylated gelatin (Geloplasma, Fresenius Kabi, Schelle, Belgium), with a reported microparticle diameter of 21 ± 6 μm (La Gerche et al. 2010), was mixed with room air (9:1 ratio) and vigorously agitated between two syringes using a three-way stopcock. A 5 ml bolus was rapidly administered while simultaneously obtaining images of the right and left heart in the apical four-chamber view. Manually agitated gelatin bubbles create an opacification of the right ventricle but do not usually traverse the pulmonary circulation at rest (Kaul, 1997; Cabanes et al. 2002). The agitated gelatin bubbles have a similar but more consistent size and superior enhancement of Doppler signals when compared to agitated saline bubbles (Tan et al. 2002). A positive PTAC was defined as the appearance of contrast bubbles in the left atrium more than four cardiac cycles following opacification of the right ventricle (Stickland et al. 2004). Opacification of the left ventricle was graded on a scale from 0 to 4 according to the number of observed bubbles (La Gerche et al. 2010). PTAC grade was obtained at maximal exercise in all individuals and at each exercise level in a subgroup of 11 individuals.

Pulmonary function and lung diffusing capacity

Measurements of slow and forced vital capacity were performed in a sitting position on a commercially available pulmonary function system (Hyp’Air compact, Medisoft, Dinant, Belgium) before measuring resting diffusing capacity. Measurements of DL,CO and DL,NO were performed as previously described (Glenet et al. 2007) with automated calibrations, extemporaneous mixing of gases and online calculations, and corrections for hemoglobin and inspired partial pressure of oxygen (Hyp’Air compact, Medisoft, Dinant, Belgium). DL,CO and its components pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) and alveolo-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) were calculated using the Roughton–Forster relationship (Roughton & Forster, 1957). Vc was corrected for a reference value of haemoglobin concentration of 14.6 g dl−1 for men and 13.4 g dl−1 for women. Duplicate measurements of DL,CO and DL,NO were performed at rest in the sitting position and in the semi-recumbent tilted position and an average of both measures is reported. During exercise, measurements were performed at 0 W and at every other stage, allowing a minimum of 4 min between DL,NO/DL,CO measurements.

Data analysis and statistics

Multipoint MPPA– plots were tested for linearity and linear regressions were calculated for pooled measurements after Poon's adjustment for individual variability (Poon, 1988). Poon's adjustment is a procedure consisting of averaging the individual response curves, thereby minimising intersubject variability while preserving any intrinsic linearity. In order to calculate the pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, each multipoint MPPA–

plots were tested for linearity and linear regressions were calculated for pooled measurements after Poon's adjustment for individual variability (Poon, 1988). Poon's adjustment is a procedure consisting of averaging the individual response curves, thereby minimising intersubject variability while preserving any intrinsic linearity. In order to calculate the pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, each multipoint MPPA– plot was also fitted to the equation:

plot was also fitted to the equation:

|

where R0 is the total pulmonary vascular resistance (MPPA/ ) at rest where the transmural pressure of the pulmonary arterial bed is minimal, Pla is left atrial pressure and α represents a percentage change in diameter for each mmHg increase in transmural pressure (Linehan et al. 1992). We solved the equation for α using the method of successive iterations. Using given values for R0 and the measured values for Pla and

) at rest where the transmural pressure of the pulmonary arterial bed is minimal, Pla is left atrial pressure and α represents a percentage change in diameter for each mmHg increase in transmural pressure (Linehan et al. 1992). We solved the equation for α using the method of successive iterations. Using given values for R0 and the measured values for Pla and  at rest and for each incrementing workload, we varied α until we found the value that gave the minimal average difference and standard deviation between measured and calculated MPPA over the whole range of measured

at rest and for each incrementing workload, we varied α until we found the value that gave the minimal average difference and standard deviation between measured and calculated MPPA over the whole range of measured  . To investigate the effect of exercise on α, a specific α index was calculated using MPPA–

. To investigate the effect of exercise on α, a specific α index was calculated using MPPA– values at rest only, MPPA–

values at rest only, MPPA– values over the entire exercise test, and MPPA–

values over the entire exercise test, and MPPA– values at peak exercise only. Student's t test for paired data was used to test for the effect of maximal exercise on echocardiographic and lung diffusing capacity measurements. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used for the analysis of associations between variables. Multivariate linear regressions were performed to investigate the ability of (1) resting values of Dm, Vc, total pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) and α to predict

values at peak exercise only. Student's t test for paired data was used to test for the effect of maximal exercise on echocardiographic and lung diffusing capacity measurements. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used for the analysis of associations between variables. Multivariate linear regressions were performed to investigate the ability of (1) resting values of Dm, Vc, total pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) and α to predict  , (2) maximal exercise values of Dm, Vc, total PVRI and α to predict

, (2) maximal exercise values of Dm, Vc, total PVRI and α to predict  . Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Participants’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants had a  of 41.8 ± 7.1 ml kg−1 min−1 with values ranging from 27.3 to 61.0 ml kg−1 min−1. The maximal workload achieved during the incremental exercise test was 163 ± 42 W, varying from 80 to 260 W. Maximal exercise was associated with a reduction in

of 41.8 ± 7.1 ml kg−1 min−1 with values ranging from 27.3 to 61.0 ml kg−1 min−1. The maximal workload achieved during the incremental exercise test was 163 ± 42 W, varying from 80 to 260 W. Maximal exercise was associated with a reduction in  (98.4 ± 1.0 vs. 95.4 ± 2.2%, P < 0.01). As reported in Table 2, maximal exercise was associated with increases in DL,CO, DL,NO, Dm and Vc as well as in left atrial pressure, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, MPPA, Pcap,

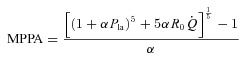

(98.4 ± 1.0 vs. 95.4 ± 2.2%, P < 0.01). As reported in Table 2, maximal exercise was associated with increases in DL,CO, DL,NO, Dm and Vc as well as in left atrial pressure, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, MPPA, Pcap,  , CI, heart rate and stroke volume, while PVRI decreased and DL,NO/DL,CO ratio did not change. Individual MPPA–CI plots obtained during the incremental exercise test are presented before and after Poon's adjustment in Fig. 1. The average MPPA–CI slope and intercept before Poon's adjustment were 3.36 ± 0.95 mmHg min l−1 m2 and 6.75 mmHg, and after Poon's adjustment were 3.22 ± 0.53 mmHg min l−1 m2 and 6.93 mmHg. The average pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α for all individuals was 1.5 ± 0.7% mmHg−1 at rest, 1.1 ± 0.3% mmHg−1 over the entire exercise test, and 0.9 ± 0.3% mmHg−1 at maximal exercise.

, CI, heart rate and stroke volume, while PVRI decreased and DL,NO/DL,CO ratio did not change. Individual MPPA–CI plots obtained during the incremental exercise test are presented before and after Poon's adjustment in Fig. 1. The average MPPA–CI slope and intercept before Poon's adjustment were 3.36 ± 0.95 mmHg min l−1 m2 and 6.75 mmHg, and after Poon's adjustment were 3.22 ± 0.53 mmHg min l−1 m2 and 6.93 mmHg. The average pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α for all individuals was 1.5 ± 0.7% mmHg−1 at rest, 1.1 ± 0.3% mmHg−1 over the entire exercise test, and 0.9 ± 0.3% mmHg−1 at maximal exercise.

Table 2.

Haemodynamic and lung diffusing capacity measurements at rest and during maximal exercise

| Rest | Maximal exercise | |

|---|---|---|

| DL,CO (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | 35.3 ± 6.4 | 44.7 ± 8.2* |

| DL,NO (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | 176.3 ± 34.1 | 219.6 ± 44.7* |

| DL,NO/DL,CO | 5.00 ± 0.29 | 4.90 ± 0.28 |

| Dm (ml min−1 mmHg−1) | 90 ± 17 | 111 ± 23* |

| Vc (ml) | 100 ± 18 | 128 ± 23* |

| LVOT diameter (cm) | 2.17 ± 0.18 | — |

| Left atrial pressure (mmHg) | 7.3 ± 2.0 | 8.9 ± 1.6* |

| Pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (mmHg) | 23 ± 3 | 61 ± 5* |

| MPPA (mmHg) | 16 ± 4 | 39 ± 7* |

| Total PVRI (Wood unit/m2) | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 0.3* |

| Pcap (mmHg) | 10 ± 2 | 21 ± 3* |

(l min−1) (l min−1) |

4.8 ± 1.2 | 19.1 ± 4.5* |

| CI (l min m−2) | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 10.1 ± 2.2* |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 60 ± 10 | 169 ± 14* |

| Stroke volume (ml) | 81 ± 21 | 111 ± 23* |

P < 0.05 between rest and maximal exercise. DL,CO: lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; DL,NO: lung diffusing capacity for nitric oxide; Dm: alveolar-capillary membrane conductance; Vc: pulmonary capillary blood volume; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; MPPA: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PVRI: pulmonary vascular resistance index; Pcap: pulmonary capillary pressure;  : cardiac output, CI: cardiac index.

: cardiac output, CI: cardiac index.

Figure 1. Individual mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPPA)–cardiac index (CI) plots obtained during the incremental exercise test before (A) and after Poon's adjustment (B) for individual variability.

Following Poon's adjustment, the average MPPA–CI slope and intercept were 3.23 mmHg min l−1 and 6.93 mmHg with an R2 value of 0.94.

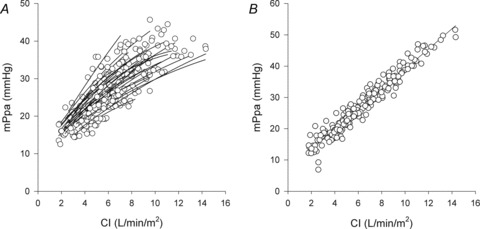

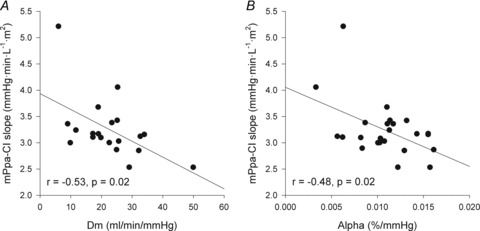

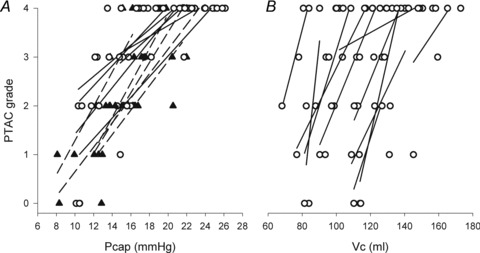

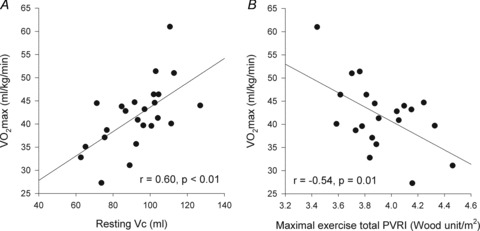

Higher α and greater changes in Dm from rest to exercise were negatively correlated to the slope of the MPPA–CI relationship (Fig. 2). Exercise-induced PTAC was observed in all individuals. At maximal exercise, only one individual was classified as low PTAC (grade 2) and 23 as high PTAC (two grade 3 and 21 grade 4). A grading of PTAC was obtained at each exercise level in a subgroup of 11 individuals. The increase in PTAC grade was proportional to increases in Pcap (r = 0.76, P < 0.01) and Vc (r = 0.41, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3). Maximal values of Vc were correlated to maximal values of Pcap (r = 0.43, P = 0.05). Individuals with the highest PTAC–Pcap slopes (n = 5) during exercise had smaller changes in MPPA from rest to maximal exercise (21 ± 4 vs. 27 ± 4 mmHg, P = 0.01), a lower maximal MPPA (36 ± 5 vs. 44 ± 6 mmHg, P = 0.02), smaller changes in CI from rest to maximal exercise (6.8 ± 1.6 vs. 9.2 ± 1.4 l min−1 m−2, P = 0.03), and a lower maximal CI (9.4 ± 1.6 vs. 11.7 ± 2.1 l min−1 m−2, P = 0.04) than individuals with lower PTAC–Pcap slopes (Fig. 3A). Using multivariate linear regressions, independent predictors of  were resting and maximal exercise pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, resting values of Vc and maximal exercise values of total PVRI (Fig. 4).

were resting and maximal exercise pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, resting values of Vc and maximal exercise values of total PVRI (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Relationships between the slope of the MPPA–CI relationship and changes in alveolar-capillary membrane conductance (Dm) from rest to exercise (A) and pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α (B)

Figure 3. Relationships between pulmonary transit agitated contrast (PTAC) grade and pulmonary capillary pressure (Pcap) (A) and pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) during exercise (B).

Individuals with highest PTAC–Pcap slopes (filled triangles, dashed lines) and individuals with lowest PTAC–Pcap slopes (open circles, continuous lines).

Figure 4.

Relationships between maximal aerobic capacity ( O2max) and its independent predictors resting values of pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) (A) and maximal exercise values of total pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) (B)

O2max) and its independent predictors resting values of pulmonary capillary blood volume (Vc) (A) and maximal exercise values of total pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) (B)

Discussion

The present results show that, in healthy individuals,  is predicted by a more distensible pulmonary circulation and a greater pulmonary capillary blood volume, which is in keeping with the notion that a greater ‘pulmonary vascular reserve’ allows for a higher aerobic exercise capacity. A pulmonary transit of agitated contrast turned out to be a common finding, essentially related to each individual's pulmonary capillary pressure or blood volume.

is predicted by a more distensible pulmonary circulation and a greater pulmonary capillary blood volume, which is in keeping with the notion that a greater ‘pulmonary vascular reserve’ allows for a higher aerobic exercise capacity. A pulmonary transit of agitated contrast turned out to be a common finding, essentially related to each individual's pulmonary capillary pressure or blood volume. decreased at maximal exercise. However, the change in

decreased at maximal exercise. However, the change in  was minimal, in accordance with previous reports (Lovering et al. 2008; La Gerche et al. 2010). The observed decrease corresponded to an only mild degree of exercise-induced arterial hypoxaemia, which would be essentially explained by exercise-associated changes in temperature and pH (Dempsey & Wagner, 1999). The majority of our participants had high PTAC, which is consistent with the observation by La Gerche et al. (2010) that individuals with low PTAC were older (39 ± 8 years), and consistent with descriptions of reduced microvascular distensibility with ageing (Reeves et al. 2005). This massive PTAC in almost all participants at maximal exercise suggests pulmonary shunting. However, true pulmonary shunting would have caused a much more important fall in

was minimal, in accordance with previous reports (Lovering et al. 2008; La Gerche et al. 2010). The observed decrease corresponded to an only mild degree of exercise-induced arterial hypoxaemia, which would be essentially explained by exercise-associated changes in temperature and pH (Dempsey & Wagner, 1999). The majority of our participants had high PTAC, which is consistent with the observation by La Gerche et al. (2010) that individuals with low PTAC were older (39 ± 8 years), and consistent with descriptions of reduced microvascular distensibility with ageing (Reeves et al. 2005). This massive PTAC in almost all participants at maximal exercise suggests pulmonary shunting. However, true pulmonary shunting would have caused a much more important fall in  (Hopkins et al. 2009a). It has been argued that PTAC would occur through parallel pulmonary pathways that do not participate to gas exchange (Eldridge et al. 2004; Stickland et al. 2004; Lovering et al. 2009). Even though such pathways may be anatomically identified (Stickland et al. 2007), blood flow through them would immediately cause true shunt and hypoxaemia. Studies using the multiple inert gas elimination technique have shown that during heavy exercise with 100% oxygen breathing, less than 0.5% of cardiac output eventually bypasses alveolar gas exchange (Vogiatzis et al. 2008). Therefore, it does not seem that a PTAC reflects significant true pulmonary shunting (Hopkins et al. 2009a).

(Hopkins et al. 2009a). It has been argued that PTAC would occur through parallel pulmonary pathways that do not participate to gas exchange (Eldridge et al. 2004; Stickland et al. 2004; Lovering et al. 2009). Even though such pathways may be anatomically identified (Stickland et al. 2007), blood flow through them would immediately cause true shunt and hypoxaemia. Studies using the multiple inert gas elimination technique have shown that during heavy exercise with 100% oxygen breathing, less than 0.5% of cardiac output eventually bypasses alveolar gas exchange (Vogiatzis et al. 2008). Therefore, it does not seem that a PTAC reflects significant true pulmonary shunting (Hopkins et al. 2009a).

The injected contrast medium consisted in gelatin microspheres particles of an average of 20 μm diameter, but ranging from 9 to 33 μm (La Gerche et al. 2010). There was a twofold increase in calculated Pcap, to a maximum average of 20 mmHg, along with a 20–30% increase in pulmonary capillary blood volume. Previous studies on isolated lungs showed that increased distending pressures may dilate capillaries up to 13 μm, with alveolar corner vessels dilating up to 20 μm diameter (Rosenzweig et al. 1970; Hughes, 2009). Corner vessels are exposed to interstitial lung pressures and thus present with a greater transmural pressure than alveolar capillaries. Exercise is associated with large inspiratory pleural and interstitial pressure swings, which may markedly increase the transmural pressure of corner vessels. Altogether, these data suggest that PTAC occurred through dilated pulmonary capillaries, probably mainly corner vessels.

Exercise was associated with an increase in lung diffusing capacity, with no change or minimal decrease in DL,NO/DL,CO ratio, indicating a predominant increase in Vc (Glenet et al. 2007), and in accordance with previous reports of increases in Dm and Vc as calculated at variable oxygen tension during exercise (Johnson et al. 1960). Predominant increase in Vc compared to Dm during exercise has been confirmed by measurements using CO and NO as tracer gases (Hsia et al. 1995). A greater increase in Vc relative to the increase in Dm suggests a predominance of capillary distension rather than recruitment (Johnson et al. 1960), which is in keeping with the notion that exercise is associated with an increased diameter of pulmonary capillaries. Thus, it appears that it was the amount of blood in the pulmonary capillaries which determined the predictive capability of lung diffusing capacity of aerobic exercise capacity.

In the present study, the functional state of the pulmonary circulation was evaluated by multipoint pulmonary vascular pressure–flow plots. This approach allows for an improved definition of pulmonary vascular resistance as compared to an isolated determination at rest (Reeves et al. 1989; Reeves et al. 2005). The average slope of MPPA– reported in invasive haemodynamic studies varies from 1 mmHg l−1 min−1 in young adults to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 in advanced age (Reeves et al. 1989). Similar slopes ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 have been recently reported using non-invasive stress echocardiography (Argiento et al. 2010; La Gerche et al. 2010). In the present study on young adults, the slope of MPPA–

reported in invasive haemodynamic studies varies from 1 mmHg l−1 min−1 in young adults to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 in advanced age (Reeves et al. 1989). Similar slopes ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 mmHg l−1 min−1 have been recently reported using non-invasive stress echocardiography (Argiento et al. 2010; La Gerche et al. 2010). In the present study on young adults, the slope of MPPA– plots averaged 1.8 mmHg l−1 m−2, which is in good agreement with these previous reports.

plots averaged 1.8 mmHg l−1 m−2, which is in good agreement with these previous reports.

When a sufficient number of MPPA– coordinates are generated at exercise, usually at least four to five points, it is possible to show that the slope of MPPA–

coordinates are generated at exercise, usually at least four to five points, it is possible to show that the slope of MPPA– decreases slightly and in a curvilinear fashion (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992; Krenz & Dawson, 2003). This curvilinearity is explained by the natural distensibility of pulmonary resistive vessels, which has been shown to be in the order of 2% change in diameter per mmHg distending pressure, either directly measured in vitro or calculated from multipoint MPPA–

decreases slightly and in a curvilinear fashion (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992; Krenz & Dawson, 2003). This curvilinearity is explained by the natural distensibility of pulmonary resistive vessels, which has been shown to be in the order of 2% change in diameter per mmHg distending pressure, either directly measured in vitro or calculated from multipoint MPPA– plots using a distensibility model of the pulmonary circulation (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992). In the present study, the distensibility α calculated from multipoint MPPA–

plots using a distensibility model of the pulmonary circulation (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992). In the present study, the distensibility α calculated from multipoint MPPA– was 1.5% mmHg−1, decreasing to 0.9% mmHg−1 at maximal exercise. It has been estimated that this distensibility would predict a sufficient increase in capillary diameter allowing for the passage of 20 μm microspheres (Eldridge et al. 2004). However, although α may not vary according to vessel segment (Reeves et al. 2005), the value calculated on MPPA–

was 1.5% mmHg−1, decreasing to 0.9% mmHg−1 at maximal exercise. It has been estimated that this distensibility would predict a sufficient increase in capillary diameter allowing for the passage of 20 μm microspheres (Eldridge et al. 2004). However, although α may not vary according to vessel segment (Reeves et al. 2005), the value calculated on MPPA– plots probably mainly reflects the distensibility of resistive arterioles. The capillary network contributes to pulmonary vascular resistance (Cope et al. 1992), and therefore also to the slope of MPPA–

plots probably mainly reflects the distensibility of resistive arterioles. The capillary network contributes to pulmonary vascular resistance (Cope et al. 1992), and therefore also to the slope of MPPA– , but the exact proportion remains unknown. α was somewhat lower than in previous reports, which may be explained by a male predominance of the participants (18/6) as it has been recently reported that α is lower in men than women (Argiento et al. 2012). The decrease in α at high levels of exercise is also in keeping with previous findings (Argiento et al. 2012) and can be explained by the notion that pulmonary vascular compliance decreases along with increases in distending pressures. Vascular distension is an obvious cause of decreased pulmonary vascular resistance at exercise, as also reported in the present study.

, but the exact proportion remains unknown. α was somewhat lower than in previous reports, which may be explained by a male predominance of the participants (18/6) as it has been recently reported that α is lower in men than women (Argiento et al. 2012). The decrease in α at high levels of exercise is also in keeping with previous findings (Argiento et al. 2012) and can be explained by the notion that pulmonary vascular compliance decreases along with increases in distending pressures. Vascular distension is an obvious cause of decreased pulmonary vascular resistance at exercise, as also reported in the present study.

While increased MPPA limits exercise capacity in pulmonary hypertension through a decreased maximum flow output by an overloaded right ventricle (Champion et al. 2009), it has only been recently suggested that the same mechanism may play a role in healthy individuals exercising at high workloads (La Gerche et al. 2010). The normal right ventricle is a thin-walled flow generator that is not designed to cope with increased afterload corresponding to brisk rises in MPPA (Champion et al. 2009). MPPA values approximating 40 mmHg are reached by individuals exercising at workloads corresponding to cardiac outputs between 15 and 20 l min−1 (Reeves et al. 1989; Bossone et al. 1999; Argiento et al. 2010), which is similar to values reported in the present study. The corresponding increase in power is relatively much more important for the right ventricle as compared to the left ventricle (Lovering & Stickland, 2010). La Gerche et al. (2010) showed that individuals with the steepest MPPA– relationships had no or minimal PTAC while individuals with high PTAC had a greater

relationships had no or minimal PTAC while individuals with high PTAC had a greater  and a lower total pulmonary vascular resistance, possibly due to an enhanced capillary distensibility. In support of these previous findings, we observed that individuals with the greatest pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α and Vc, along with the lowest PVRI at maximum exercise, had the highest

and a lower total pulmonary vascular resistance, possibly due to an enhanced capillary distensibility. In support of these previous findings, we observed that individuals with the greatest pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α and Vc, along with the lowest PVRI at maximum exercise, had the highest  . The increase in PTAC grade was proportional to increases in Pcap suggesting that a greater Pcap leads to a greater passage of bubbles. Moreover, we showed that individuals with the highest PTAC–Pcap slopes during exercise had smaller changes in MPPA, further suggesting that the Pcap-induced passage of bubbles acts act as ‘pop-off valves’ in response to increases in flow and pulmonary vascular resistance (Berk et al. 1977). It is therefore believed that increases in Pcap lead to capillary distension and bubble passage, a contention supported by the observed proportional increases between PTAC grade and Vc. It is possible that increased driving pressure allowed deformation of contrast particles, thereby squeezing them through the pulmonary capillary network.

. The increase in PTAC grade was proportional to increases in Pcap suggesting that a greater Pcap leads to a greater passage of bubbles. Moreover, we showed that individuals with the highest PTAC–Pcap slopes during exercise had smaller changes in MPPA, further suggesting that the Pcap-induced passage of bubbles acts act as ‘pop-off valves’ in response to increases in flow and pulmonary vascular resistance (Berk et al. 1977). It is therefore believed that increases in Pcap lead to capillary distension and bubble passage, a contention supported by the observed proportional increases between PTAC grade and Vc. It is possible that increased driving pressure allowed deformation of contrast particles, thereby squeezing them through the pulmonary capillary network.

Estimation of MPPA from measurements of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure and measures of  during exercise are challenging. We calculated MPPA from measurements of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure using a previously validated equation derived from tight correlations with invasive pulmonary haemodynamic measurements at rest and during exercise (Chemla et al. 2004; Syyed et al. 2008). Moreover, the multiple measures (average of 8 workloads) of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure and

during exercise are challenging. We calculated MPPA from measurements of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure using a previously validated equation derived from tight correlations with invasive pulmonary haemodynamic measurements at rest and during exercise (Chemla et al. 2004; Syyed et al. 2008). Moreover, the multiple measures (average of 8 workloads) of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure and  performed in our study allowed us to derive a trend throughout exercise. Our maximal MPPA values were in agreement with previously reported values approximating 40 mmHg in individuals exercising at workloads corresponding to cardiac outputs between 15 and 20 l min−1 (Reeves et al. 1989; Bossone et al. 1999; Argiento et al. 2010). There are also conflicting reports about the effect of exercise on left atrial pressure, with studies reporting marked increases in left atrial pressure (Reeves et al. 1989) while others report no changes in left atrial pressure during maximal exercise (Argiento et al. 2010). Some of these conflicting results may be due to the high variability in resting left atrial pressure measurements estimated from E/E′ or to the absence of linear relationship between E/E′ and wedged pulmonary arterial pressure at exercise (Talreja et al. 2007). We observed a slight increase of approximately 2 mmHg in left atrial pressure at an average maximal workload of 160 W and an average maximal cardiac output of 19 l min−1 in our participants. This slight increase in left atrial pressure is consistent with previous findings suggesting that a greater work intensity and cardiac output are necessary to induce a ‘take-off’ of left atrial pressure in healthy individuals (Stickland et al. 2006). However, limitation in this measure did not affect the calculation of pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, as our α measurements were in agreement with α values directly measured in vitro or calculated from multipoint MPPA–

performed in our study allowed us to derive a trend throughout exercise. Our maximal MPPA values were in agreement with previously reported values approximating 40 mmHg in individuals exercising at workloads corresponding to cardiac outputs between 15 and 20 l min−1 (Reeves et al. 1989; Bossone et al. 1999; Argiento et al. 2010). There are also conflicting reports about the effect of exercise on left atrial pressure, with studies reporting marked increases in left atrial pressure (Reeves et al. 1989) while others report no changes in left atrial pressure during maximal exercise (Argiento et al. 2010). Some of these conflicting results may be due to the high variability in resting left atrial pressure measurements estimated from E/E′ or to the absence of linear relationship between E/E′ and wedged pulmonary arterial pressure at exercise (Talreja et al. 2007). We observed a slight increase of approximately 2 mmHg in left atrial pressure at an average maximal workload of 160 W and an average maximal cardiac output of 19 l min−1 in our participants. This slight increase in left atrial pressure is consistent with previous findings suggesting that a greater work intensity and cardiac output are necessary to induce a ‘take-off’ of left atrial pressure in healthy individuals (Stickland et al. 2006). However, limitation in this measure did not affect the calculation of pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α, as our α measurements were in agreement with α values directly measured in vitro or calculated from multipoint MPPA– plots using a distensibility model of the pulmonary circulation (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992).

plots using a distensibility model of the pulmonary circulation (Reeves et al. 1989; Linehan et al. 1992).

In conclusion, we observed that individuals with the greatest pulmonary arteriolar distensibility α and pulmonary capillary blood volume, along with the lowest PVRI at maximum exercise, had the highest  . Agitated contrast commonly transits through the pulmonary circulation at exercise, in proportion to the increases in pulmonary capillary pressures and pulmonary capillary blood volume.

. Agitated contrast commonly transits through the pulmonary circulation at exercise, in proportion to the increases in pulmonary capillary pressures and pulmonary capillary blood volume.

Acknowledgments

P.Y. was the recipient of grants from the Fondation Vaudoise de Cardiologie and from the Fondation SICPA. S.L. was the recipient of a European Respiratory Society/Marie Curie postdoctoral fellowship. The study was funded by FRSM grant no. 3.4637.09.

Glossary

- CI

cardiac index

- CO

carbon monoxide

- DL,CO

lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide

- DL,NO

lung diffusing capacity for nitric oxide

- Dm

alveolar-capillary membrane conductance

- E

early flow velocity

- E′

mitral annulus early velocity

- LVOT

left ventricular outflow tract

- MPPA

mean pulmonary arterial pressure

- NO

nitric oxide

- Pcap

pulmonary capillary pressure

- PTAC

pulmonary transit of agitated contrast

- PVRI

pulmonary vascular resistance index

cardiac output

- RER

respiratory exchange ratio

pulse oximetry oxygen saturation

- TRV

tricuspid regurgitation

- TVI

time–velocity integral

maximal aerobic capacity

- Vc

pulmonary capillary blood volume

-

/

/

slope of ventilation relative to carbon dioxide production

Author contributions

This experiment was performed in the Laboratory of Cardiorespiratory Physiology of the Faculté des Sciences de la Motricité at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. Each author contributed to the following aspects of the study: conception and design of the experiments: S.L., P.Y., R.N.; collection, analysis and interpretation of data: S.L., P.Y., V.F., R.N.; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: S.L., P.Y., V.F., R.N. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Argiento P, Chesler N, Mule M, D’Alto M, Bossone E, Unger P, Naeije R. Exercise stress echocardiography for the study of the pulmonary circulation. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1273–1278. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiento P, Vanderpool RR, Mule M, Russo MG, D’Alto M, Bossone E, Chesler NC, Naeije R. Exercise stress echocardiography of the pulmonary circulation: limits of normal and gender differences. Chest. 2012 doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0071. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk JL, Hagen JF, Tong RK, Maly G. The use of dopamine to correct the reduced cardiac output resulting from positive end-expiratory pressure. A two-edged sword. Crit Care Med. 1977;5:269. doi: 10.1097/00003246-197711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossone E, Rubenfire M, Bach DS, Ricciardi M, Armstrong WF. Range of tricuspid regurgitation velocity at rest and during exercise in normal adult men: implications for the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1662–1666. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes L, Coste J, Derumeaux G, Jeanrenaud X, Lamy C, Zuber M, Mas JL. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in detection of patent foramen ovale and atrial septal aneurysm with transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:441–446. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.116718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion HC, Michelakis ED, Hassoun PM. Comprehensive invasive and noninvasive approach to the right ventricle-pulmonary circulation unit: state of the art and clinical and research implications. Circulation. 2009;120:992–1007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemla D, Castelain V, Humbert M, Hebert JL, Simonneau G, Lecarpentier Y, Herve P. New formula for predicting mean pulmonary artery pressure using systolic pulmonary artery pressure. Chest. 2004;126:1313–1317. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie J, Sheldahl LM, Tristani FE, Sagar KB, Ptacin MJ, Wann S. Determination of stroke volume and cardiac output during exercise: comparison of two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography, Fick oximetry, and thermodilution. Circulation. 1987;76:539–547. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DK, Grimbert F, Downey JM, Taylor AE. Pulmonary capillary pressure: a review. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:1043–1056. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Wagner PD. Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1997–2006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition. 1989;5:303–311. discussion 312–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge MW, Dempsey JA, Haverkamp HC, Lovering AT, Hokanson JS. Exercise-induced intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunting in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:797–805. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00137.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenet SN, De Bisschop C, Vargas F, Guenard HJ. Deciphering the nitric oxide to carbon monoxide lung transfer ratio: physiological implications. J Physiol. 2007;582:767–775. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenard H, Varene N, Vaida P. Determination of lung capillary blood volume and membrane diffusing capacity in man by the measurements of NO and CO transfer. Resp Physiol. 1987;70:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(87)80036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SR, Olfert IM, Wagner PD. Last Word on Point:Counterpoint: Exercise-induced intrapulmonary shunting is imaginary vs. real. J Appl Physiol. 2009a;107:1002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00652.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SR, Olfert IM, Wagner PD. Point: Exercise-induced intrapulmonary shunting is imaginary. J Appl Physiol. 2009b;107:993–994. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91489.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, McBrayer DG, Ramanathan M. Reference values of pulmonary diffusing capacity during exercise by a rebreathing technique. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:658–665. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JM. Let's find out the size of these “shunts”. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1000. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2009. discussion 1997–1008, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Jr, Spicer WS, Bishop JM, Forster RE. Pulmonary capillary blood volume, flow and diffusing capacity during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1960;15:893–902. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1960.15.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S. Myocardial contrast echocardiography: 15 years of research and development. Circulation. 1997;96:3745–3760. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz GS, Dawson CA. Flow and pressure distributions in vascular networks consisting of distensible vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2192–2203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00762.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Gerche A, MacIsaac AI, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, Inder WJ, Voigt JU, Heidbuchel H, Prior DL. Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast is associated with enhanced pulmonary vascular reserve and right ventricular function during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1307–1317. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00457.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan JH, Haworth ST, Nelin LD, Krenz GS, Dawson CA. A simple distensible vessel model for interpreting pulmonary vascular pressure-flow curves. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:987–994. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.3.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering AT, Eldridge MW, Stickland MK. Counterpoint: Exercise-induced intrapulmonary shunting is real. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:994–997. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91489.2008a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering AT, Romer LM, Haverkamp HC, Pegelow DF, Hokanson JS, Eldridge MW. Intrapulmonary shunting and pulmonary gas exchange during normoxic and hypoxic exercise in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1418–1425. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00208.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering AT, Stickland MK. Not hearing is believing: novel insight into cardiopulmonary function using agitated contrast and ultrasound. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1290–1291. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01083.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeije R, Faoro V. Pathophysiological insight into shunted bubbles. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:999–1000. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2009. discussion 1997–1008, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Quinones MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CS. Analysis of linear and mildly nonlinear relationships using pooled subject data. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:854–859. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves J, Dempsey J, Grover R. Pulmonary Vascular Physiology and Physiopathology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1989. Pulmonary circulation during exercise. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JT, Linehan JH, Stenmark KR. Distensibility of the normal human lung circulation during exercise. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L419–425. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00162.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Roisin R, Krowka MJ. Hepatopulmonary syndrome – a liver-induced lung vascular disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2378–2387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig DY, Hughes JM, Glazier JB. Effects of transpulmonary and vascular pressures on pulmonary blood volume in isolated lung. J Appl Physiol. 1970;28:553–560. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughton FJ, Forster RE. Relative importance of diffusion and chemical reaction rates in determining rate of exchange of gases in the human lung, with special reference to true diffusing capacity of pulmonary membrane and volume of blood in the lung capillaries. J Appl Physiol. 1957;11:290–302. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1957.11.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin CL, Letarte M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia and pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: issues in clinical management and review of pathogenic mechanisms. Thorax. 1999;54:714–729. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickland MK, Lovering AT, Eldridge MW. Exercise-induced arteriovenous intrapulmonary shunting in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:300–305. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-206OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickland MK, Welsh RC, Haykowsky MJ, Petersen SR, Anderson WD, Taylor DA, Bouffard M, Jones RL. Intra-pulmonary shunt and pulmonary gas exchange during exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561:321–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickland MK, Welsh RC, Petersen SR, Tyberg JV, Anderson WD, Jones RL, Taylor DA, Bouffard M, Haykowsky MJ. Does fitness level modulate the cardiovascular hemodynamic response to exercise? J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1895–1901. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01485.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syyed R, Reeves JT, Welsh D, Raeside D, Johnson MK, Peacock AJ. The relationship between the components of pulmonary artery pressure remains constant under all conditions in both health and disease. Chest. 2008;133:633–639. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talreja DR, Nishimura RA, Oh JK. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressure with exercise by Doppler echocardiography in patients with normal systolic function: a simultaneous echocardiographic-cardiac catheterization study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:477–479. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan HC, Fung KC, Kritharides L. Agitated colloid is superior to saline and equivalent to levovist in enhancing tricuspid regurgitation Doppler envelope and in the opacification of right heart chambers: a quantitative, qualitative, and cost-effectiveness study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:309–315. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.116717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogiatzis I, Zakynthinos S, Boushel R, Athanasopoulos D, Guenette JA, Wagner H, Roussos C, Wagner PD. The contribution of intrapulmonary shunts to the alveolar-to-arterial oxygen difference during exercise is very small. J Physiol. 2008;586:2381–2391. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yock PG, Popp RL. Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 1984;70:657–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]