Abstract

Human atrial transient outward K+ current (ITO) is decreased in a variety of cardiac pathologies, but how ITO reduction alters action potentials (APs) and arrhythmia mechanisms is poorly understood, owing to non-selectivity of ITO blockers. The aim of this study was to investigate effects of selective ITO changes on AP shape and duration (APD), and on afterdepolarisations or abnormal automaticity with β-adrenergic-stimulation, using the dynamic-clamp technique in atrial cells. Human and rabbit atrial cells were isolated by enzymatic dissociation, and electrical activity recorded by whole-cell-patch clamp (35–37°C). Dynamic-clamp-simulated ITO reduction or block slowed AP phase 1 and elevated the plateau, significantly prolonging APD, in both species. In human atrial cells, ITO block (100%ITO subtraction) increased APD50 by 31%, APD90 by 17%, and APD−61 mV (reflecting cellular effective refractory period) by 22% (P < 0.05 for each). Interrupting ITO block at various time points during repolarisation revealed that the APD90 increase resulted mainly from plateau-elevation, rather than from phase 1-slowing or any residual ITO. In rabbit atrial cells, partial ITO block (∼40%ITO subtraction) reversibly increased the incidence of cellular arrhythmic depolarisations (CADs; afterdepolarisations and/or abnormal automaticity) in the presence of the β-agonist isoproterenol (0.1 μm; ISO), from 0% to 64% (P < 0.05). ISO-induced CADs were significantly suppressed by dynamic-clamp increase in ITO (∼40%ITO addition). ISO+ITO decrease-induced CADs were abolished by β1-antagonism with atenolol at therapeutic concentration (1 μm). Atrial cell action potential changes from selective ITO modulation, shown for the first time using dynamic-clamp, have the potential to influence reentrant and non-reentrant arrhythmia mechanisms, with implications for both the development and treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Key points

The shape of the cardiac atrial action potential is influenced by the flow of a transient outward K+ current (ITO) across atrial muscle cell membranes.

Whether changes in ITO could alter atrial cell action potentials in ways that could affect mechanisms of abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) is unclear, because currently available ITO blocking drugs are non-selective.

We used the ‘dynamic-clamp’ technique, for the first time in atrial cells isolated from patients, and from rabbits, to electrically simulate selective changes in ITO during action potential recording.

We found that ITO decrease prolonged atrial cell action potential duration and, under β-adrenergic-stimulation, provoked abnormal membrane potential oscillations (afterdepolarisations) that were preventable by ITO increase or a β-blocker.

These results help us better understand the contribution of ITO to atrial cell action potential shape and mechanisms of arrhythmia, with potential implications for both the development and treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Introduction

The cardiac transient outward K+ current (ITO) activates rapidly upon action potential (AP) initiation. Its large magnitude in atrial cells of many species, including human, and in ventricular cells of some rodents contributes to the characteristic spiky AP shape in these cells, with fast early repolarisation (phase 1) and small plateau (Xu et al. 1999; Workman et al. 2000; Workman et al. 2001; Sah et al. 2002; Madhvani et al. 2011). In such cells, ITO reduction can markedly alter AP shape. For example, in atrial (Xu et al. 1999) and ventricular (Sah et al. 2002) cells from mice genetically engineered for reduced ITO, the plateau was elevated and AP duration at late (90%) repolarisation (APD90) markedly prolonged. ITO reduction has the potential, therefore, to influence various electrophysiological mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Plateau elevation may cause afterdepolarisations or abnormal automaticity, particularly during adrenergic elevation (Workman, 2010), and APD90 increase may inhibit reentry (Workman et al. 2011).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, and atrial ITO is markedly reduced in chronic AF and in several predisposing pathologies, by electrophysiological remodelling (Le Grand et al. 1994; Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Nattel et al. 2007; Christ et al. 2008; Workman et al. 2008; Workman et al. 2009; Schotten et al. 2011; Dobrev et al. 2012). Furthermore, some drugs used in the treatment of AF also inhibit ITO (Wang et al. 1995; Varro et al. 1996; Gross & Castle, 1998; Marshall et al. 2012). The rapid activation of this current means that its reduction, by affecting membrane voltage (Vm) early during repolarisation, has knock-on (secondary) effects on other voltage-gated currents, e.g. L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) and resultant Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) and Na+/Ca2+-exchanger current (INa/Ca) (Sah et al. 2003) with inevitable complex, species- and pathology-dependent influences on the plateau and APD90.

However, it is unclear what effect ITO reduction has on atrial APs in humans and most other mammals, because of the non-specificity of the best available ITO blocker, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP). This drug additionally blocks ultra-rapid delayed rectifier K+ current (IKur) (Wang et al. 1993), and although atrial IKur may be small in some species, e.g. rabbit (Giles & Imaizumi, 1988; Lindblad et al. 1996), its large magnitude in human atrium (Wang et al. 1993; Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Christ et al. 2008) necessitates the use of other tools for studying effects of ITO reduction. Mathematical modelling is a powerful alternative, but yielded variable results depending on the algorithm used and intrinsic AP shape, and on constraining electrophysiological parameters (Courtemanche et al. 1998; Nygren et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 2005; Grandi et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2012). Moreover, such models can only incorporate known experimental data. The dynamic-clamp technique (Wilders, 2006), however, provides the opportunity to reduce ITO selectively in live atrial cells. A voltage- and time-dependent current based on a mathematical model of ITO is calculated in real-time as a function of the cell's Vm, and injected into the cell with opposite polarity during AP recording, thus cancelling out defined fractions of ITO. Dynamic-clamping has previously been used to alter ventricular ITO or ICaL (Sun & Wang, 2005; Dong et al. 2006; Dong et al. 2010; Madhvani et al. 2011) and a stretch-activated current in rat atrial cells (Wagner et al. 2004), but not so far to alter ITO in atrial cells. No ion current has been studied previously using dynamic-clamping in human atrial cells.

The aim, therefore, was to investigate effects of selective, graded changes in ITO on AP shape and APD, and on afterdepolarisations or abnormal automaticity in the presence of β-adrenergic-stimulation, using the dynamic-clamp technique in human and rabbit atrial cells.

Methods

Ethical approval

Procedures and experiments involving human atrial cells were approved by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Service (REC: 99MC002). Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki. Procedures and experiments involving rabbit atrial cells (UK Project Licence No. PPL60/40206) were approved by Glasgow University Ethics Review Committee. All procedures and experiments conformed to the principles of UK regulations, as described in Drummond (2009).

Atrial cell isolation

Cells were isolated from rabbit and human atrial tissues, as described previously (Workman et al. 2000; Workman et al. 2001). Rabbits (New Zealand White, male, age 17.2 ± 1.0 weeks, weight 3.1 ± 0.1 kg; n = 24) were humanely killed by intravenous injection of anaesthetic (100 mg kg−1 pentobarbital sodium) and removal of the heart, which was retrogradely perfused via the aorta for enzymatic dissociation of left atrial cells (Workman et al. 2000). Right atrial appendage tissues were obtained from 14 adult patients (59.4 ± 2.6 years; 13 male/1 female) undergoing cardiac surgery (79%: coronary artery bypass graft; 21%: aortic valve replacement). All patients were in sinus rhythm with no history of AF; 79% had angina, 57% had hypertension, 43% had myocardial infarction, 21% had mild/moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD), 79% had no LVSD. Patients were undergoing treatment with the following cardiac drugs: β-blocker (36%), ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor-blocker (36%), Ca2+ channel blocker (29%), statin (79%), nitrate (36%), nicorandil (29%). Cells were isolated by the chunk technique (Workman et al. 2001), and stored for ≤9 h at ∼20°C in a low [Ca2+] solution containing (mm): NaCl (140), KCl (4), CaCl2 (0.18), MgCl2 (1), glucose (11) and Hepes (10); pH 7.4.

Conventional whole-cell-patch clamp technique

Cells were superfused at 35–37°C with the above solution except that [Ca2+] was 1.8 mm. Microelectrodes (1.5–5 MΩ) contained (mm): potassium aspartate (130), KCl (15), NaCl (10), MgCl2 (1), Hepes (10), EGTA (0.1); pH 7.25. Membrane currents and APs were stimulated and recorded by whole-cell-patch clamp, with an AxoClamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) and WinWCP or WinEDR software (J. Dempster). ITO was stimulated by voltage-clamping with the activation and inactivation protocols in Fig. 1A and C. Pulse frequency was 0.1 Hz for rabbit, 0.33 Hz for human. ITO amplitude was calculated as peak outward minus end-pulse current, thus avoiding the slowly inactivating IKur and other slowly or non-inactivating current components that contribute to total outward current in human atrial cells (Christ et al. 2008). Extracellular Cd2+ (0.2 mm) blocked ICaL. Trains of APs were stimulated at 50–600 beats min−1 by current-clamping in bridge mode with 3–5 ms pulses, 1.2–1.5× threshold. Most human atrial cells required a small (0.87 ± 0.19 pA pF−1, n = 18) constant hyperpolarising current to gain ∼−80 mV resting Vm, as previously (Le Grand et al. 1994; Bénardeau et al. 1996; Workman et al. 2001).

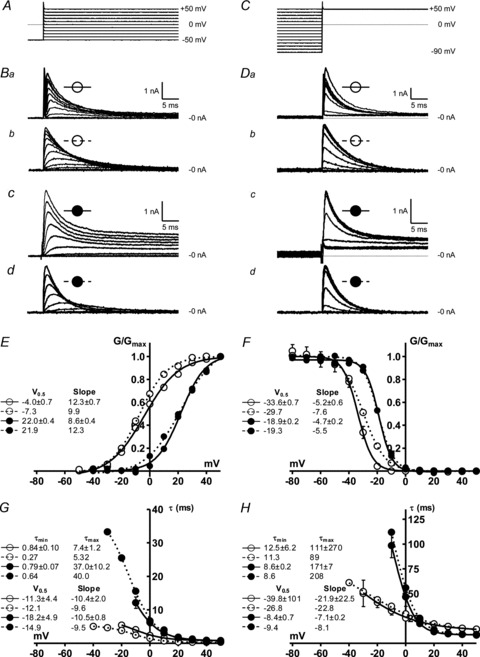

Figure 1. Comparison between live and simulated atrial ITO in rabbit and human.

Open symbols: rabbit data; filled symbols: human. Continuous lines: live atrial cell data; dashed lines: current generated by dynamic-clamp ITO models. A–D, steady-state voltage dependence: ITO activation, using voltage-clamp protocol shown in A, resulting in currents in Ba–d; ITO inactivation with protocol shown in C, resulting in currents shown in Da–d. E–H, voltage dependence of ITO activation and inactivation in live atrial cells (n = 8–15, 5–6 rabbits; 10–12 cells, 6–7 patients) or from single simulation runs. ITO steady-state activation (E) and inactivation (F) curves constructed by dividing peak ITO at each voltage by driving force to give conductance, G, and dividing G by Gmax. ITO activation (G) and inactivation (H): time constants estimated from exponential functions fitted to activation and inactivation time courses; half-activation and inactivation potentials, V0.5, and slopes, minimum and maximum time constants, τmin and τmax, estimated by fitting Boltzmann functions; values shown with corresponding curve labels.

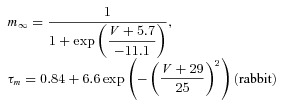

Dynamic-clamp technique

The dynamic-clamp technique was used in model-clamp configuration (Wilders, 2006) to simulate systematic changes in peak ITO conductance, in rabbit and human live atrial cells. ITO was modelled as a simple Hodgkin–Huxley voltage-activated current based upon an activating parameter, m, and an inactivating parameter, h, using the following equations, based on (Nygren et al. 1998).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

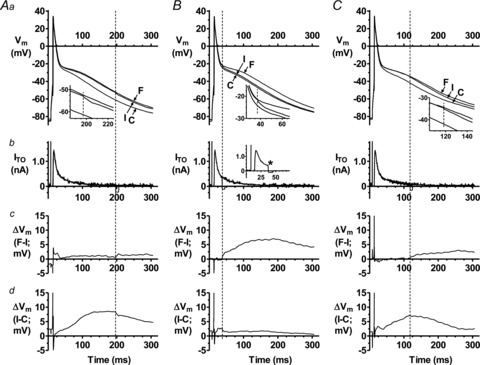

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

The voltage dependence of the steady-state activation and inactivation parameters (m∞, h∞), activation and inactivation time constant (τm, τh) and peak ITO conductance (Gmax) were derived from the average peak current and steady-state activation and inactivation curves, measured in groups of rabbit and human atrial cells (Fig. 1).

The dynamic-clamp was custom-built using an Analog Devices ADuC 7024 analog microcontroller (Analog Devices Inc., Norwood, MA, USA), incorporating a 40 MHz ARM7 microprocessor and 12 bit A/D and D/A converters. The ITO model, executing on the microcontroller, was written in C and the device controlled from a host computer via an RS232 interface. Vm was monitored and dynamic-clamp current output injected into the AxoClamp 2B stimulus current pathway at precisely timed 100 μs intervals.

Statistics

Electrophysiological data are expressed as means ± SEM. Continuous data were compared using two-sided, two-sample paired Student's t test; categorical data using a χ2-test with Yates's correction. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical and curve fitting analyses were done using Graphpad Prism 5.00 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Comparison of live and simulated atrial ITO characteristics

ITO showed characteristic rapid activation and decay (Fig. 1Ba for rabbit; Fig. 1Bc for human). A large non-inactivating current was present in human atrial cells, reflecting mainly IKur (Wang et al. 1993). Mean voltage dependence of ITO steady-state activation (Fig. 1E) and inactivation (F) differed between rabbit and human. ITO Gmax was 24.4 nS (0.34 nS pF−1) in rabbit, and 9.9 nS (0.12 nS pF−1) in human atrial cells. The time courses of ITO activation and inactivation were mono-exponential, and mean τ-voltage relationships also differed between species (Fig. 1G and H). Traces in Fig. 1B and D (dashed symbols) are dynamic-clamp (i.e. simulated) currents injected into a simple resistor (500 MΩ)–capacitor (33 pF) circuit (Patch-1 model cell, Axon Instruments) during voltage-clamp with the protocols in Fig. 1A and C. ITO was modelled as a fully inactivating current (Dong et al. 2006), so Fig. 1Bd and Dd do not contain the non-inactivating, IKur component. There was generally good agreement between live and simulated ITO in both species for ITO waveform, voltage and time dependence curves, and curve fit values (Fig. 1E–H). The largest difference was in the steady-state voltage dependence of ITO inactivation in rabbit (Fig. 1F), reflected by a 3.9 mV difference in V0.5.

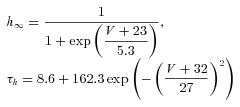

Effects of changing ITO by dynamic-clamp on rabbit atrial cell action potentials

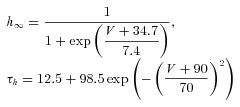

Action potentials from rabbit atrial cells had prominent phase 1 repolarisation and low amplitude plateau (Fig. 2Aa; control). Partial ITO inhibition, by dynamic-clamp subtraction of a small (5 or 10 nS) peak ITO conductance (Fig. 2Ab) slowed phase 1, elevated the plateau, and moderately increased APD (Fig. 2Aa). Twenty nanosiemens ITO subtraction, reflecting ∼80%ITO block, markedly slowed phase 1 and elevated the plateau, and prolonged APD, particularly at early-to-mid repolarisation (APD30-50). Late repolarisation (e.g. at ≥100 ms; labelled) was also prolonged by ITO subtraction, despite negligible or zero current at ≥100 ms. At approximately full ITO block (25 nS), APs had a prolonged, ‘spike & dome’ shape (Fig. 2Aa). Further (supra-physiological) ITO subtraction (30 nS) produced no extra APD increase. Addition of ITO in this cell (downward deflections in Fig. 2Ab) enhanced phase 1 and depressed the plateau (e.g. 20 nS addition in Fig. 2Aa), and moderately shortened APD at all levels of repolarisation. Mean data (Fig. 2B) revealed a non-linear relationship between ITO and APD, particularly APD20-50 due to prominent plateau elevation by ITO subtraction. Action potential maximum upstroke velocity (Vmax) was unaffected by ITO change (Fig. 2B). Full ITO block (24.4 nS ITO subtraction) significantly increased mean APD20-90, and APD−64 mV (reflecting cellular effective refractory period, ERP; Workman et al. 2000), and had no effect on Vmax (Fig. 2C). Absolute APD increase was greatest at APD50 (Fig. 2D), consistent with the plateau elevation. Nevertheless, APD90 and APD−64 mV were also increased, by ∼20 ms. Relative (%) APD increase by ITO block was markedly greater at mid than late repolarisation (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Effects of decreasing and increasing ITO conductance by dynamic-clamp on rabbit atrial cell APs.

A, superimposed action potentials (APs; a) and corresponding dynamic-clamp (D-C) currents (b) recorded from a single representative atrial cell, without D-C (Control), or with D-C subtraction or addition of ITO over a range of peak conductances (labelled). D-C subtracted ITO is +ve, because +ve charge is injected into the cell to compensate for the loss of +ve charge via native ITO. Stimulation rate = 75 beats min−1 to permit sufficient time for ITO reactivation (Giles & Imaizumi, 1988; Workman et al. 2000). P: current pulse (3 ms, ∼1.2× threshold) to stimulate APs. B, relationship between ITO conductance (–ve Δ peak ITO = D-C subtraction of ITO) and APD20-90, APD−64 mV and Vmax; n = 16 cells, 6 rabbits. Vertical arrow indicates 24.4 nS ITO subtraction, reflecting full ITO block. Effect of full ITO block on APDs and Vmax shown by comparing control (open bars) with 24.4 nS ITO subtraction (filled; *P < 0.05 vs. control, NS: not significant) (C), or as absolute (D) or relative (E) APD change.

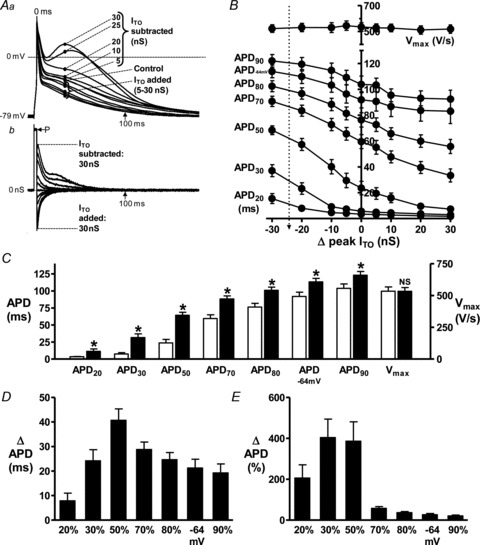

Effects of changing ITO by dynamic-clamp on human atrial cell action potentials

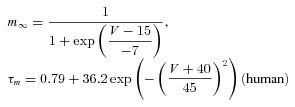

Human atrial cell APs were typically type 3 (low- or no-dome), with prominent phase 1 in control (Fig. 3Aa). A 50% inhibition of ITO, by 5 nS dynamic-clamp subtraction (Fig. 3Ab), slowed phase 1 and moderately elevated the plateau and prolonged late repolarisation; APD70-90 (Fig. 3Aa). Full ITO block (10 nS) elevated the plateau further (Fig. 3Aa), but less so than in rabbit (Fig. 2Aa) and further increased APD. The APD increase at ≥150 ms (labelled) occurred despite negligible or zero current at that time. Extra ITO subtraction (15–20 nS; supra-physiological) caused additional increase in late repolarisation and, by contrast with rabbit (Fig. 2A), little further plateau elevation. Dynamic-clamp addition of ITO accelerated phase 1, lowered the plateau and decreased late APD (Fig. 3A). Mean APD changes indicated that within the physiological range of peak ITO conductance (vertical dashed line in Fig. 3B), ITO subtraction lengthened APD, particularly APD70-90 and APD−61 mV (reflecting cellular ERP; Workman et al. 2001), and ITO increase had the opposite effects (Fig. 3B). Vmax was unaltered by ITO change (Fig. 3B). Figure 3C shows that full ITO block (9.9 nS subtraction) significantly increased APD at each repolarisation level. This was most prominent in absolute terms (Fig. 3D) for APD70-90 and APD−61 mV; relative (Fig. 3E) APD increase was similar at each level.

Figure 3. Effects of decreasing and increasing ITO by dynamic-clamp on human atrial cell APs.

A, superimposed APs (a) and corresponding D-C currents (b) recorded from a single representative human atrial cell, without D-C (Control), or with D-C subtraction (sub) or addition of ITO over a range of peak conductances. Rate = 75 beats min−1. P: current pulse (5 ms, ∼1.5× threshold) to stimulate APs. B, relationship between ITO conductance and APDs and Vmax; n = 18 cells, 6 patients. Vertical dashed arrow indicates 9.9 nS ITO subtraction, reflecting full ITO block. Effects of full ITO block shown by comparing control (empty bars) with 9.9 nS ITO subtraction (filled; *P < 0.05 vs. control) (C), or as absolute (D) or relative (E) APD change.

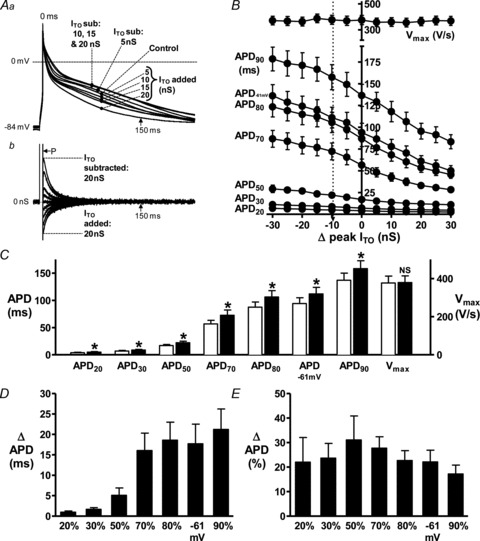

ITO reduction prolongs late repolarisation mainly by elevating action potential plateau

Figure 4Aa and b shows that interrupting the subtraction of ITO late during phase 3 (∼APD70), i.e. when current was small or zero but APD increase by ITO reduction was large, caused negligible deviation in the course of subsequent repolarisation: compare trace F with I, and see Fig. 4Aa inset. This was confirmed by subtracting I from F (Fig. 4Ac) and indicated that any residual (non-inactivated) ITO present after APD70 contributed little to the APD increase over control (I-C; Fig. 4Ad) during that time. When ITO subtraction was interrupted at the end of phase 1 (Fig. 4B), i.e. early during repolarisation but when the highest amplitude and a large portion of ITO had already occurred (current leftwards of vertical line in Fig. 4Bb), repolarisation rapidly deviated from its course of a slowed phase 1, to follow control: Fig. 4Ba and inset. This was confirmed by the small magnitude I-C (Fig. 4Bd) and indicated that the marked plateau elevation and APD70 increase caused by ITO reduction (F vs. C in Fig. 4Ba) was not a consequence of the ITO reduction during phase 1. Interrupting ITO subtraction midway through the plateau (∼APD60), i.e. at a point (vertical line in Fig. 4Ca) before which ITO reduction had markedly elevated the plateau, caused a moderate deflection in the course of subsequent repolarisation. The magnitude of F-I rightwards of the vertical line in Fig. 4Cc was larger than in 4Ac, indicating that a residual ITO block at ∼APD60 contributed, albeit to a small degree, to the APD increase during subsequent repolarisation. However, the substantially elevated plateau and prolonged APD observed well beyond the point of interrupting ITO subtraction, i.e. between APD60-90 (I-C rightwards of vertical line in Fig. 4Cd), showed that the major influence of ITO to prolong APD during that time had occurred earlier, during the plateau and after the end of phase 1, i.e. at around APD50-60.

Figure 4. ITO reduction prolongs late repolarisation mainly by elevating AP plateau.

Effect on human atrial AP late repolarisation of interrupting D-C subtraction of ITO (by temporarily switching off D-C current injection) during late repolarisation (AP phase 3; A), early repolarisation (phase 1; B), and mid repolarisation (phase 2; C), in a single cell. Rate = 75 beats min−1. Top panels (a) show superimposed, representative APs recorded without D-C subtraction of ITO (control: C), or with 9.9 nS ITO subtraction for the full (F) duration of the AP, or with D-C subtraction of ITO interrupted (I) at the point indicated by vertical dashed lines. Insets show magnified portion of APs close to point of interruption. Panels b show corresponding superimposed D-C subtraction currents. Inset in B, example of non-superimposed D-C-interrupted trace (* Point of interruption). Panels c and d, subtraction of AP trace I from F, and C from I (as in corresponding top panels).

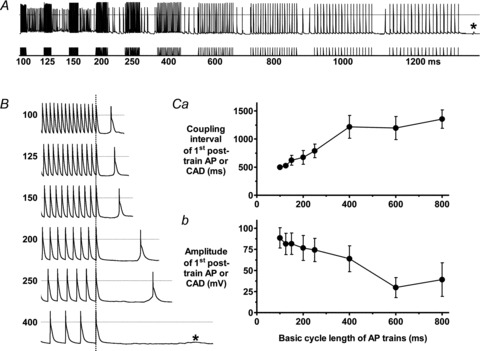

Production of spontaneous depolarisations in rabbit atrial cells: evidence for DAD component

Spontaneous APs or subthreshold transient depolar isations >3 mV (‘cellular arrhythmic depolarisations’; CADs; Redpath et al. 2006), which represent afterdepolarisations and/or abnormal automaticity (Redpath et al. 2006), occurred during 6 s pauses between AP trains, in rabbit atrial cells (Fig. 5). At BCL 800 ms (used to investigate ITO change on APD), such post-train CAD(s) occurred in 5/12 control cells and in 12/12 cells exposed to the β-receptor agonist isoproterenol (ISO) or ISO+elevated [Ca2+]o (P < 0.05). In a representative cell in which post-train CADs occurred with ISO (Fig. 5A), rapid stimulation (BCL 100 ms) resulted in a high number and frequency of these CADs. Progressive reduction in stimulation rate resulted in fewer post-train CADs, of lower frequency at each rate, and an increase in the time between the last stimulated AP and the first CAD (coupling interval). The lowest rate resulted in a subthreshold post-train CAD. Figure 5B shows a similar coupling interval increase in a different cell. Mean data (Fig. 5C) show a linear relationship between BCL and both coupling interval (panel a) and amplitude (b) between BCL 100–400 ms, indicating a delayed afterdepolarisation (DAD) component to these CADs.

Figure 5. Production of spontaneous depolarisations in rabbit atrial cells: evidence for DAD component.

A, APs (upper trace) recorded from a rabbit atrial cell during stimulation with trains of current pulses (lower trace) delivered at BCL shown, in the presence of isoproterenol (ISO) 0.1 μm. *Subthreshold CAD. B, APs in a different cell at magnified time scale at short BCLs using same protocol as A. C, BCL vs. mean (± SEM) coupling interval (a) and amplitude (b) of post-train AP or CAD with 0.1 μm ISO or 0.1 μm ISO+3.6 mm[Ca2+]. n = 10–12 cells, 5 rabbits.

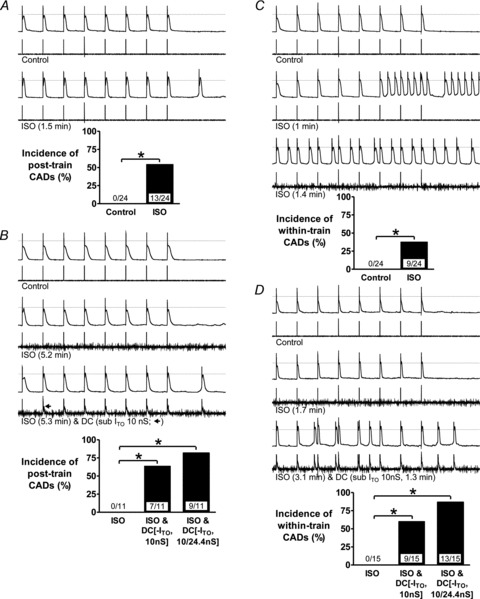

ITO reduction potentiates β-stimulation-induced CADs in rabbit atrial cells

Effects of dynamic-clamp subtraction of ITO on CADs, in the presence of ISO, were investigated in rabbit atrial cells (Fig. 6). In 24 cells in which no CAD occurred in control (e.g. Fig. 6A, top trace), ISO produced CAD(s) within the pauses between AP trains in 13 cells (e.g. Fig. 6A, lower trace), thus significantly increasing the incidence of post-train CADs (Fig. 6A, bar graph). ISO also elevated the AP plateau, including that of the CAD (Fig. 6A). ISO had no effect on peak ITO: 36.3 ± 4.8 pA pF−1 at +50 mV in control vs. 34.7 ± 4.3 pA pF−1 in ISO (P > 0.05; n = 8 cells, 4 rabbits). In the cells in which ISO did not produce post-train CADs, ITO subtraction (10 nS; ∼40%ITO block) during continued ISO elevated the plateau further than ISO alone, and significantly increased the incidence of post-train CADs (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, full ITO block produced post-train CADs in half of the cells in which partial ITO block did not. ISO also produced CADs within AP trains, typically stabilising as rapid, continuously and irregularly firing threshold depolarisations (Fig. 6C). In the 15/24 cells in which these did not occur with ISO, subsequent ITO reduction or block significantly increased the incidence of within-train CADs, again associated with marked plateau-elevation (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. ITO reduction potentiates β-stimulation-induced CADs in rabbit atrial cells.

Effects of ISO 0.1 μm with or without D-C subtraction of ITO on the incidence of CADs. Upper traces of trace pairs: AP trains (75 beats min−1) followed by 2 s pauses. Lower traces: corresponding currents: AP stimulus pulses with or without D-C reduction of ITO (of labelled conductance and duration). Bar graphs: incidences of CADs following (post-train) or during (within-train) AP trains; values within bars: cell n (≤7 rabbits), *P < 0.05. A, effect of ISO 1.5 min (max. time needed for stable effect on APs and CADs) on post-train CADs, without D-C subtraction of ITO. B, in the cells in which ISO did not produce CADs in A, effects of 10 nS ITO subtraction (3rd trace pair) and/or 24.4 nS ITO subtraction (bar graph) on post-train CADs. C and D, corresponding changes to within-train CADs.

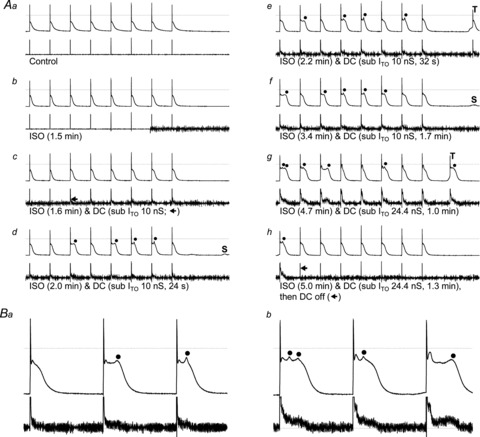

Production of EADs by ITO reduction plus β-stimulation

Transient, small amplitude depolarisations occurred during the plateau of several APs under ITO subtraction plus ISO, in 1/7 cells (Fig. 7) in which ISO alone did not produce post-train CADs but subsequent 10 nS ITO subtraction did. These plateau phase depolarisations occurred in 0/24 cells treated with ISO alone, appeared ∼20 s after ITO subtraction (Fig. 7Ad), persisted during each AP train (e.g. Fig. 7Ae–h), and disappeared upon ceasing ITO subtraction (Fig. 7Ah). One occurred on the plateau of a post-train CAD (Fig. 7Ag). Over the 2 min period of 10 nS ITO subtraction plus ISO, 117 APs were stimulated in this cell. Of those, 47 (40%) had a plateau phase depolarisation, and no CAD (threshold or subthreshold) occurred between stimulated APs (that could suggest DADs or abnormal automaticity), identifying these depolarisations as early afterdepolarisations (EADs). Figure 7B shows the EADs as distinct from the AP dome. Full (24.4 nS) ITO subtraction caused a double EAD and a ‘late phase’ EAD (Fig. 7Bb).

Figure 7. Production of EADs by ITO reduction plus β-stimulation.

A, upper traces of trace pairs: AP trains (75 beats min−1) followed by 2 s pauses; lower traces: corresponding currents, recorded in a rabbit atrial cell before (a) and after (b) ISO 0.1 μm and during subsequent D-C subtraction of ITO (c–h). •: EAD. S, subthreshold CAD; T, threshold CAD. B, expanded portions of panel A traces: a, 4th, 5th and 6th APs from Ad; b, 1st, 2nd and 3rd APs from Ag.

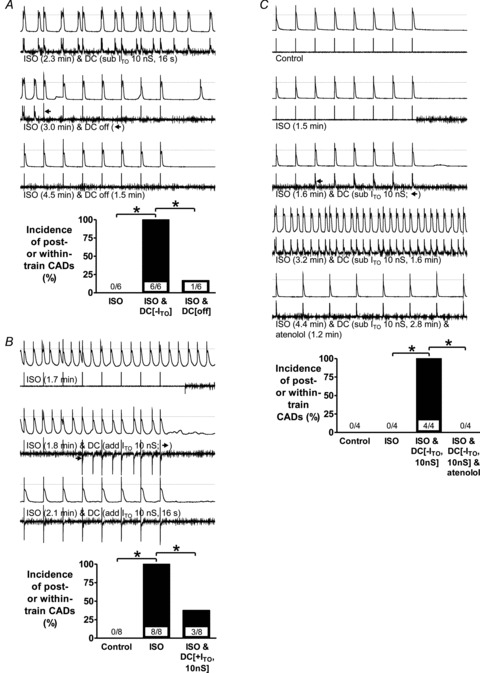

Suppression of CADs: by interrupting ITO reduction, by adding ITO, or by β1-antagonism

Suppression or abolition of CADs that were caused by ISO or concurrent ITO reduction was demonstrated using three interventions (Fig. 8). First, interrupting dynamic-clamp subtraction of ITO in the presence of ISO caused a rapid reduction in the number and frequency of CADs in most cells (e.g. Fig. 8A, 2nd trace pair), no further CADs with continued ISO, and accompanying plateau-depression (e.g. Fig. 8A, bottom trace pair). Second, increasing ITO (by ∼40%), in cells in which ISO alone produced CADs, typically rapidly and continuously suppressed these CADs, accompanied by plateau depression (e.g. Fig. 8B, bottom trace pair), significantly reducing their incidence (Fig. 8B, bar graph). Reversibility was assessed in four cells: interrupting ITO addition caused CADs to return in each. Third, β1-receptor antagonism with atenolol abolished CADs caused by decreased ITO in the presence of ISO (Fig. 8C). In each of four cells in which ISO did not produce CADs but subsequent ITO subtraction did (e.g. Fig. 8C, top 4 trace pairs) atenolol, in the continued presence of ISO and ITO reduction, abolished these CADs (e.g. Fig. 8C, bottom trace pair), significantly decreasing their incidence (Fig. 8C, bar graph).

Figure 8. Suppression of CADs by interrupting ITO reduction, by adding ITO, or by β1-antagonism.

Upper traces of trace pairs: AP trains (75 beats min−1) followed by 2 s pauses; lower traces: corresponding currents, recorded in rabbit atrial cells. Bar graphs show incidences of CADs (combined post- and within-train); values within bars: cell n, *P < 0.05. A, effect of interrupting D-C subtraction of ITO on CADs in cells (3 rabbits) in which ISO did not produce CADs but concurrent D-C subtraction of ITO (10 or 24.4 nS) did. B, effect of D-C addition of ITO on CADs in cells (4 rabbits) in which ISO produced CADs. C, effect of atenolol (1 μm) on CADs in cells (3 rabbits) in which ISO did not produce CADs but concurrent D-C subtraction of ITO did.

Discussion

The key findings are that selective ITO reduction, simulated in live atrial cells for the first time to our knowledge using dynamic-clamping, elevated the action potential plateau and prolonged late repolarisation (APD70-90) in human and rabbit, and promoted afterdepolarisations or abnormal automaticity under β-adrenergic-stimulation.

Plateau elevation by ITO subtraction was most prominent in rabbit, and terminal repolarisation (APD90) was increased by ∼20% in both species. It was previously unclear what effect ITO reduction would have on human atrial APD90, because the best available ITO blocker, 4-AP, inhibits IKur at ≥40-fold lower concentration than ITO (Wang et al. 1993), human atrial IKur is large (Wang et al. 1993; Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Christ et al. 2008), and selective IKur reduction affects human atrial APD90 (Wang et al. 1993; Wettwer et al. 2004). However, IKur is notoriously difficult to separate completely from ITO, and we cannot exclude the possibility that our ITO model included a component of rapidly inactivating IKur, as reported by Christ et al. (2008). Nevertheless, we were able to exclude the large, slowly inactivating IKur and other non-inactivating current components (Christ et al. 2008) and, therefore, use the dynamic-clamp as a novel intervention to improve our understanding of the contribution of ITO to human atrial cell APD and arrhythmia mechanisms.

Studies of effects of selective IKur block have shown some similarities to, and important differences from, the present effects of ITO block. Thus, in atrial trabeculae from patients in sinus rhythm, micromolar 4-AP elevated the plateau, but, by contrast with ITO block, here, shortened APD90, probably from secondary increase in delayed rectifier K+ currents (Wettwer et al. 2004). Increase in both plateau and APD90, however, have also been reported in human atrial cells (Wang et al. 1993). In canine atrial cells, C9356, an IKur(d) blocker, increased the plateau, APD20 and APD50, but with negligible effect on APD90 (Fedida et al. 2003). Combined ITO/IKur block in human atrial cells, with millimolar 4-AP, increased both plateau and APD90, by ∼30% (Workman et al. 2001). The novel IKur/ITO/IKACh blocker, AVE0118, had negligible effect on APD90 (Wettwer et al. 2004; Schotten et al. 2007; Christ et al. 2008), but elevated the plateau (Wettwer et al. 2004; Schotten et al. 2007; Christ et al. 2008) and increased systolic [Ca2+]i and contractility (Schotten et al. 2007). Furthermore, Schotten et al. (2007) showed, using various AP-clamping techniques, that such change in the AP shape was responsible for this drug's positive inotropic action. Thus, in the absence of AVE0118, atrial cell fractional shortening was markedly increased either by elevating the plateau amplitude or by prolonging its duration (without changing APD90), or indeed by imposing the AP waveform recorded under AVE0118.

Previous dynamic-clamp studies of ITO used ventricular cells, from dog or guinea-pig. In epicardial cells, which have a moderate phase 1 ‘notch’ due to ITO, an ITO subtraction sufficient to eliminate this notch did not affect subsequent repolarisation (Sun & Wang, 2005). In endocardial cells, which had small or no ITO or notch, ITO addition sufficient to produce a notch also lacked effect on repolarisation (Dong et al. 2006; Dong et al. 2010). However, ventricular AP shape, some ion currents, and [Ca2+]i handling differ markedly from atrial, including in human (Grandi et al. 2011), and the relatively large atrial ITO and phase 1 in human (Grandi et al. 2011) and rabbit (Giles & Imaizumi, 1988) are likely to account for the observed relatively strong atrial APD response to ITO decrease.

The magnitude of the human atrial APD90 increase with ITO subtraction (i.e. 9% with 50%ITO subtraction) and block (17% with 100%ITO subtraction) is consistent with several mathematical models. Thus, in the Grandi model (Grandi et al. 2011), 50 and 100%ITO decrease lengthened APD90 by 9 and 19%, respectively. In the Nygren model (Nygren et al. 1998), 90%ITO decrease also lengthened APD90, by 18%. By contrast, in the Courtemanche–Ramirez–Nattel (CRN) model (Courtemanche et al. 1998), 50 or 90%ITO decrease shortened APD90. Another study, based on the CRN model, also reported APD90 shortening (Zhang et al. 2005). However, the CRN model generates a type 1 (spike and dome) AP, whereas the present APs and those generated by the other models (Nygren et al. 1998; Grandi et al. 2011) are type 3. Moreover, modification of the CRN model to generate type 3 s (Marshall et al. 2012) reversed the effect of ITO decrease: a 41% decrease lengthened APD90 by 9% (Marshall et al. 2012), again consistent with present data.

The increased APD90 and APD−61 mV by ITO reduction has implications for atrial reentry. APD−61 mV estimates cellular ERP, because −61 mV is the mean Vm from which partially refractory APs took off in human atrial cells (Workman et al. 2001). Since leading circle reentry wavelength (λ) = ERP × conduction velocity (θ), then increased APD−61 mV, with the unchanged Vmax (a determinant of θ), has the potential to increase λ and thus inhibit reentry (Workman et al. 2011). Furthermore, ITO reduction may terminate spiral wave reentry, by plateau elevation alone, according to a CRN-based mathematical model of human atrial two-dimensional reentry (Pandit et al. 2005). Atrial electrophysiological remodelling in chronic AF and predisposing pathologies such as atrial dilatation and LVSD invariably involves ITO reduction (Le Grand et al. 1994; Van Wagoner et al. 1997; Nattel et al. 2007; Christ et al. 2008; Workman et al. 2008; Workman et al. 2009; Schotten et al. 2011; Dobrev et al. 2012). However, several other currents remodel also, which are likely to have more bearing on atrial ERP than ITO, despite secondary ionic effects of ITO reduction, making the consequences of ITO reduction difficult to predict. For example, increased inward rectifier K+ current (IK1 and IKACh) and altered [Ca2+]i handling are likely to be the principle mechanisms of ERP-shortening in chronic AF (Dobrev et al. 2005; Cha et al. 2006; Workman et al. 2008; Dobrev et al. 2012; Voigt et al. 2012). Human atrial ERP increase, by chronic β-blockade (Workman et al. 2003), was associated with decreased ITO and IK1 (Marshall et al. 2012), and mathematical modelling suggested a small contribution from ITO (Marshall et al. 2012). It is conceivable that ERP increase by some other drugs used to treat AF, e.g. flecainide, propafenone and amiodarone, could also involve their observed inhibition of ITO (Wang et al. 1995; Varro et al. 1996; Gross & Castle, 1998), in addition to their recognised effects on other ion currents and [Ca2+]i handling (Dobrev et al. 2012). Since only ITO decrease was detected in patients with LVSD, associated with atrial ERP shortening (Workman et al. 2009), the present data indicate that other, as yet unidentified, ionic mechanisms were responsible for the ERP shortening in that study (Workman et al. 2009).

Critically timed interruption of ITO subtraction during human atrial repolarisation revealed that the present APD90 prolongation was not caused by ITO reduction during phase 1, nor by reduction of any substantial residual ITO flowing during late repolarisation (APD70 or beyond), but rather by the effect of ITO reduction between these points, i.e. mid plateau (APD50-60), to elevate the plateau. The mid plateau-to-APD90 region is substantially maintained by forward mode (depolarising) INa/Ca from Ca2+ extrusion after CICR: INa/Ca block with Li+ approximately halved APD−60 mV (Bénardeau et al. 1996). In mouse ventricular cells, which also have type 3 APs, genetic ITO reduction slowed ICaL inactivation and increased net Ca2+ influx via ICaL, and markedly increased systolic [Ca2+]i (Sah et al. 2002). The increased net ICaL in that study is likely to have contributed substantially to the increased [Ca2+]i, but increased reverse-mode INa/Ca (Ca2+ influx) may also contribute, since plateau elevation may shift Vm towards ENa/Ca (Sah et al. 2003). Indeed, support for such a contribution from reverse-mode INa/Ca was provided by the AP-clamp studies in canine atrial cells from Schotten et al (2007). They showed that, in control cells, imposing the AP waveform recorded under AVE0118 (a drug which markedly elevated the plateau by inhibiting IKur and ITO, and increased systolic [Ca2+]i and contractility) had negligible effect on net Ca2+ influx via ICaL despite also increasing contractility, yet inhibition of reverse-mode INa/Ca (using KBR7943 or elimination of pipette Na+) abolished this AP-clamp-induced positive inotropic effect (Schotten et al. 2007). Irrespective of the mechanism of systolic [Ca2+]i increase resulting from selective reduction in ITO, a consequent increase in depolarising INa/Ca is a likely contributory mechanism for the effect of ITO decrease to prolong APD90 in the present study. Furthermore, INa/Ca is the major current responsible for DADs and abnormal automaticity, especially during adrenergic stimulation, which increases ICaL amplitude, sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ content, and thus systolic [Ca2+]i (Workman, 2010).

Afterdepolarisations (DADs and EADs) and abnormal automaticity have complex, partially shared mechanisms of generation and are difficult to distinguish, hence their grouping here as CADs (Redpath et al. 2006). We found a DAD component in rabbit atrial cells under β-stimulation, since post-train CADs showed a rate dependence of coupling interval and amplitude characteristic of DADs (Johnson et al. 1986). Nevertheless, ISO produced a variety of spontaneous activities, during and after trains, so we did not restrict investigation of ITO change to DADs. ISO was used at Emax concentration for ICaL (Redpath et al. 2006), and had no effect on ITO. When ISO alone did not produce CADs, it nevertheless elevated the plateau. Subsequent ITO subtraction produced immediate (within 1 beat) further plateau elevation, and CADs followed either within a few beats or after several AP trains, their incidence increasing with strength of ITO subtraction. It is reasonable to suppose that these CADs resulted from the marked plateau elevation from concurrent ITO subtraction and β-stimulation, each of which increases [Ca2+]i (Sah et al. 2002; Dong et al. 2010; Workman, 2010), with consequent [Ca2+]i loading sufficient to produce DADs and/or abnormal automaticity via spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ release and subsequent inward INa/Ca. Furthermore, in one cell, ISO plus ITO subtraction produced EADs, distinguished by their consistent, regular appearance during phase 2, with no DADs or abnormal automaticity. The Vm from which they arose (−25 to −15 mV) centred on ‘window ICaL’ (where ICaL activation and inactivation curves overlap; −30 to −10 mV in rabbit atrium; Lindblad et al. 1996), consistent with a recognised mechanism of EAD generation: APD increase at window ICaL voltages. The contribution of window ICaL to EADs was studied by dynamic-clamping ICaL in rabbit ventricular cells (Madhvani et al. 2011). EAD formation was modified by only small changes in ICaL voltage dependence that did not change [Ca2+]i (Madhvani et al. 2011). However, effects of ITO change on window ICaL remain to be studied. Atrial DADs and/or EADs occur in several animal models of congestive heart failure (CHF)-induced AF (Nattel et al. 2007; Schotten et al. 2011; Dobrev et al. 2012). Since these models also feature decreased atrial ITO and increased APD and/or INa/Ca (Nattel et al. 2007; Schotten et al. 2011; Dobrev et al. 2012), it is conceivable that ITO decrease may contribute to atrial afterdepolarisation formation in CHF. CADs were suppressed, in the present study, by removal of ITO subtraction, or by dynamic-clamp addition of ITO. The associated AP (or CAD) plateau depression in each case is consistent with suppression of CADs by opposition of [Ca2+]i loading. CADs were also suppressed by atenolol, used here at therapeutic concentration, 1 μm (de Abreu et al. 2003), probably involving antagonism of [Ca2+]i loading produced by β-stimulation of ICaL and CICR (Workman, 2010).

Study limitations

(1) We did not study cells from patients with AF, and since chronic AF remodels atrial ion currents and [Ca2+]i handling (Schotten et al. 2011; Dobrev et al. 2012), it may be expected to alter APD responses to ITO change, as shown for some other currents. For example, block of IKur (Wettwer et al. 2004) or IKur/ITO/IKACh (Wettwer et al. 2004; Christ et al. 2008) increased APD90 in atrial trabeculae from patients with chronic AF, but not sinus rhythm. Chronic AF also increased the propensity for atrial DADs, by increasing diastolic sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ leak and INa/Ca (Voigt et al. 2012), and so could also alter effects of ITO change on DADs. Whether chronic AF could affect the propensity to EADs, and hence their response to ITO change, is unclear. (2) Whilst the modelled ITO generally conformed well to the live data, with a maximum V0.5 discrepancy of <4 mV, an influence of such a difference on the dynamic-clamped AP cannot be excluded. (3) Rabbit and human atrial ITO is carried by different pore-forming α-subunits: Kv1.4 and Kv4.3, respectively (Wang et al. 1999), which confer markedly different reactivation kinetics and rate-dependence of ITO between these species. At the stimulation rate (75 beats min−1) and temperature (35–37°C) used for all the dynamic-clamp experiments, human atrial ITO would reactivate fully between beats, whereas rabbit atrial ITO would be ∼50% reactivated (Fermini et al. 1992) due to its relatively slow reactivation kinetics. We did not model this slow reactivation, and our rabbit atrial ITO model therefore incorporated more ‘human-like’ reactivation kinetics than occur in vivo. Nevertheless, a subtraction of ∼40% of the fully reactivated ITO significantly increased the incidence of afterdepolarisations in the rabbit atrial cells. (4) The holding current required in human (not rabbit) atrial cells to gain ∼−80 mV resting Vm, although kept constant in each cell and independent of dynamic-clamp current, is nevertheless recognised to shorten APD and depress the plateau. Such effects could lead to an underestimation of the potential for ITO reduction to produce arrhythmogenic activity in human atrial cells in vivo, but an overestimation of the potential for ITO addition to prevent such activity. (5) Whole-cell-patch clamp uses fixed intracellular and extracellular solutions, and the isolated cells also lack electrotonic influence from other cells. (6) The dynamic-clamp was used here to mimic the electrical effects of ITO reduction. However, it is recognised that this technique cannot mimic local [K+] changes (Wilders, 2006).

In conclusion, changes in atrial cell action potential shape and durations from selective ITO modulation, shown here for the first time using dynamic-clamp, have the potential to influence reentrant and non-reentrant arrhythmia mechanisms, with implications for both the development and treatment of AF.

Acknowledgments

We thank the cardiothoracic surgical team, Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Glasgow for providing human atrial tissue, and Catherine Hawksby, Aileen Rankin and Michael Dunne, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, for technical assistance, and Francis Burton, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, for helpful discussion. This work was supported by BHF Basic Science Lectureship Renewal BS/06/003 (A.J.W.) and BHF Clinical PhD Studentship FS/04/087 (G.E.M.).

Glossary

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- APD

action potential duration

- APDx

action potential duration at x% repolarisation

- BCL

basic cycle length

- CAD

cellular arrhythmic depolarisation

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- CRN

Courtemanche–Ramirez–Nattel

- DAD

delayed afterdepolarisation

- EAD

early afterdepolarisation

- ERP

effective refractory period

- h∞

steady-state inactivation parameter

- ICaL

L-type Ca2+ current

- IK1

inward rectifier K+ current

- IKACh

acetylcholine-activated K+ current

- IKur

ultra-rapid delayed rectifier K+ current

- INa/Ca

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current

- ISO

isoproterenol

- ITO

transient outward K+ current

- ITOGmax

peak ITO conductance

- LVSD

left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- m∞

steady-state activation parameter

- V0.5

voltage of half activation or inactivation

- Vm

membrane voltage

- Vmax

action potential maximum upstroke velocity

- τh

inactivation time constant

- τm

activation time constant

Author contributions

Conception and design of the experiments: A.J.W., J.D., G.L.S., A.C.R. Collection, analysis and interpretation of data: A.J.W., J.D., G.E.M., A.C.R., G.L.S. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: A.J.W., J.D., A.C.R., G.L.S., G.E.M. Final approval of the published version: A.J.W., G.E.M., A.C.R., G.L.S., J.D. All experiments were performed in the laboratory of the British Heart Foundation (BHF) Glasgow Cardiovascular Research Centre, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow. The authors have no disclosures.

References

- Bénardeau A, Hatem SN, Rücker-Martin C, Le Grand B, Macé L, Dervanian P, Mercadier J-J, Coraboeuf E. Contribution of Na+/Ca2+ exchange to action potential of human atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;271:H1151–H1161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha TJ, Ehrlich JR, Chartier D, Qi XY, Xiao L, Nattel S. Kir3-based inward rectifier potassium current: potential role in atrial tachycardia remodeling effects on atrial repolarization and arrhythmias. Circulation. 2006;113:1730–1737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Wettwer E, Voigt N, Hala O, Radicke S, Matschke K, Varro A, Dobrev D, Ravens U. Pathology-specific effects of the IKur/Ito/IK,ACh blocker AVE0118 on ion channels in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche M, Ramirez RJ, Nattel S. Ionic mechanisms underlying human atrial action potential properties: insights from a mathematical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H301–H321. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Abreu LRP, de Castro SAC, Pedrazzoli J., Jr Atenolol quantification in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography: application to bioequivalence study. AAPS PharmSci. 2003;5:1–7. doi: 10.1208/ps050221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev D, Carlsson L, Nattel S. Novel molecular targets for atrial fibrillation therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:275–291. doi: 10.1038/nrd3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrev D, Friedrich A, Voigt N, Jost N, Wettwer E, Christ T, Knaut M, Ravens U. The G protein-gated potassium current IK,ACh is constitutively active in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;112:3697–3706. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Sun X, Prinz AA, Wang H-S. Effect of simulated Ito on guinea pig and canine ventricular action potential morphology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H631–H637. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00084.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Yan S, Chen Y, Niklewski PJ, Sun X, Chenault K, Wang HS. Role of the transient outward current in regulating mechanical properties of canine ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Eldstrom J, Hesketh JC, Lamorgese M, Castel L, Steele DF, Van Wagoner DR. Kv1.5 is an important component of repolarizing K+ current in canine atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;93:744–751. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000096362.60730.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermini B, Wang Z, Duan D, Nattel S. Differences in rate dependence of transient outward current in rabbit and human atrium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H1747–H1754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Comparison of potassium currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular cells. J Physiol. 1988;405:123–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi E, Pandit SV, Voigt N, Workman AJ, Dobrev D, Jalife J, Bers DM. Human atrial action potential and Ca2+ model: sinus rhythm and chronic atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2011;109:1055–1066. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GJ, Castle NA. Propafenone inhibition of human atrial myocyte repolarizing currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:783–793. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N, Danilo P, Jr, Wit AL, Rosen MR. Characteristics of initiation and termination of catecholamine-induced triggered activity in atrial fibers of the coronary sinus. Circulation. 1986;74:1168–1179. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand B, Hatem S, Deroubaix E, Couetil JP, Coraboeuf E. Depressed transient outward and calcium currents in dilated human atria. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:548–556. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad DS, Murphey CR, Clark JW, Giles WR. A model of the action potential and underlying membrane currents in a rabbit atrial cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;271:H1666–H1696. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhvani RV, Xie Y, Pantazis A, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN, Olcese R. Shaping a new Ca2+ conductance to suppress early afterdepolarizations in cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2011;589:6081–6092. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GE, Russell JA, Tellez JO, Jhund PS, Currie S, Dempster J, Boyett MR, Kane KA, Rankin AC, Workman AJ. Remodelling of human atrial K+ currents but not ion channel expression by chronic β-blockade. Pflugers Arch. 2012;463:537–548. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S, Maguy A, Le Bouter S, Yeh YH. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:425–456. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren A, Fiset C, Firek L, Clark JW, Lindblad DS, Clark RB, Giles WR. Mathematical model of an adult human atrial cell: the role of K+ currents in repolarization. Circ Res. 1998;82:63–81. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit SV, Berenfeld O, Anumonwo JMB, Zaritski RM, Kneller J, Nattel S, Jalife J. Ionic determinants of functional reentry in a 2-D model of human atrial cells during simulated chronic atrial fibrillation. Biophys J. 2005;88:3806–3821. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.060459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redpath CJ, Rankin AC, Kane KA, Workman AJ. Anti-adrenergic effects of endothelin on human atrial action potentials are potentially anti-arrhythmic. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah R, Oudit GY, Nguyen TTT, Lim HW, Wickenden AD, Wilson GJ, Molkentin JD, Backx PH. Inhibition of calcineurin and sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx protects cardiac morphology and ventricular function in Kv4.2N transgenic mice. Circulation. 2002;105:1850–1856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014211.47830.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Trivieri MG, Zobel C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation–contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current (Ito. J Physiol. 2003;546:5–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten U, de Haan S, Verheule S, Harks EGA, Frechen D, Bodewig E, Greiser M, Ram R, Maessen J, Kelm M, Allessie M, Van Wagoner DR. Blockade of atrial-specific K+-currents increases atrial but not ventricular contractility by enhancing reverse mode Na+/Ca2+-exchange. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, Goette A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:265–325. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wang HS. Role of the transient outward current (Ito) in shaping canine ventricular action potential – a dynamic clamp study. J Physiol. 2005;564:411–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, McCarthy PM, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM. Outward K+ current densities and Kv1.5 expression are reduced in chronic human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 1997;80:772–781. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varro A, Virag L, Papp JG. Comparison of the chronic and acute effects of amiodarone on the calcium and potassium currents in rabbit isolated cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:1181–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt N, Li N, Wang Q, Wang W, Trafford AW, Abu-Taha I, Sun Q, Wieland T, Ravens U, Nattel S, Wehrens XHT, Dobrev D. Enhanced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and increased Na+-Ca2+ exchanger function underlie delayed afterdepolarizations in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;125:2059–2070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner MB, Kumar R, Joyner RW, Wang Y. Induced automaticity in isolated rat atrial cells by incorporation of a stretch-activated conductance. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:819–829. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Feng J, Shi H, Pond A, Nerbonne JM, Nattel S. Potential molecular basis of different physiological properties of the transient outward K+ current in rabbit and human atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 1999;84:551–561. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Sustained depolarisation-induced outward current in human atrial myocytes. Evidence for a novel delayed rectifier K+ current similar to Kv1.5 cloned channel currents. Circ Res. 1993;73:1061–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fermini B, Nattel S. Effects of flecainide, quinidine, and 4-aminopyridine on transient outward and ultrarapid delayed rectifier currents in human atrial myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Thera. 1995;272:184–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Hala O, Christ T, Heubach JF, Dobrev D, Knaut M, Varro A, Ravens U. Role of IKur in controlling action potential shape and contractility in the human atrium: influence of chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:2299–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145155.60288.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilders R. Dynamic clamp: a powerful tool in cardiac electrophysiology. J Physiol. 2006;576:349–359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ. Cardiac adrenergic control and atrial fibrillation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381:235–249. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0474-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. The contribution of ionic currents to changes in refractoriness of human atrial myocytes associated with chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:226–235. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. Cellular bases for human atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:S1–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Kane KA, Russell JA, Norrie J, Rankin AC. Chronic beta-adrenoceptor blockade and human atrial cell electrophysiology: evidence of pharmacological remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:518–525. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. Rate-dependency of action potential duration and refractoriness in isolated myocytes from the rabbit AV node and atrium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1525–1537. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Pau D, Redpath CJ, Marshall GE, Russell JA, Norrie J, Kane KA, Rankin AC. Atrial cellular electrophysiological changes in patients with ventricular dysfunction may predispose to AF. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman AJ, Smith GL, Rankin AC. Mechanisms of termination and prevention of atrial fibrillation by drug therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131:221–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Li H, Nerbonne JM. Elimination of the transient outward current and action potential prolongation in mouse atrial myocytes expressing a dominant negative Kv4 α subunit. J Physiol. 1999;519:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0011o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Garratt CJ, Zhu J, Holden AV. Role of up-regulation of IK1 in action potential shortening associated with atrial fibrillation in humans. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]