Abstract

The objective of this review is to summarise the available evidence on the frequency and management of incidental findings in imaging diagnostic tests. Original articles were identified by a systematic search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library Plus databases using appropriate medical headings. Extracted variables were study design; sample size; type of imaging test; initial diagnosis; frequency and location of incidental findings; whether clinical follow-up was performed; and whether a definitive diagnosis was made. Study characteristics were assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreement was solved by consensus. The relationship between the frequency of incidental findings and the study characteristics was assessed using a one-way ANOVA test, as was the frequency of follow-up of incidental findings and the frequency of confirmation. 251 potentially relevant abstracts were identified and 44 articles were finally included in the review. Overall, the mean frequency of incidental findings was 23.6% (95% confidence interval (CI) 15.8–31.3%). The frequency of incidental findings was higher in studies involving CT technology (mean 31.1%, 95% CI 20.1–41.9%), in patients with an unspecific initial diagnosis (mean 30.5, 95% CI 0–81.6) and when the location of the incidental findings was unspecified (mean 33.9%, 95% CI 18.1–49.7). The mean frequency of clinical follow-up was 64.5% (95% CI 52.9–76.1%) and mean frequency of clinical confirmation was 45.6% (95% CI 32.1–59.2%). Although the optimal strategy for the management of these abnormalities is still unclear, it is essential to be aware of the low clinical confirmation in findings of moderate and major importance.

Imaging techniques play a major role in the management of many patients. The quality of imaging examinations has improved considerably and access to these new devices has increased, assuming that “newer is better” [1]. However, these techniques often give rise to findings that are incidental to the reason the study was ordered. The growing number of imaging techniques performed per patient causes an increase in the number of incidental findings. How these findings should be managed is far from settled.

A classical example of an incidental finding is an adrenal mass discovered unexpectedly through imaging examinations, dubbed “incidentalomas” [2]. Other incidental findings include the unexpected pulmonary nodules observed during chest imaging tests, which have been subject to particular research attention owing to their potential clinical relevance [3].

The description of an unexpected finding can trigger additional medical care including unnecessary tests, other diagnostic procedures and treatments which in some cases may pose an additional risk to the patient. This process has been called the “cascade effect” [4]. Clinicians need to know how to deal with unexpected findings in order to avoid any undesirable consequences. The absence of convincing evidence from controlled studies leads to unawareness of the prognostic significance and treatment implications for unexpected findings. However, there are some studies describing the frequency of these findings in different clinical settings, using several imaging techniques, and providing some recommendations to deal with them.

The aim of this review was to appraise the prevalence of incidental findings in clinical practice according to several relevant variables.

Methods and materials

The systematic review was conducted to assess the frequency of incidental findings reported in imaging diagnostic techniques, the follow-up and the degree of confirmation of these findings, and the related variables. We defined an incidental finding as any abnormality not related to the illness or causes that prompted the diagnostic imaging test.

Search strategy

We searched all articles published until 31 December 2007. The MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library Plus databases were searched by using exploded headings under the terms: incidental finding, unexpected finding, clinical cascade, serendipity (by using the Boolean operator OR), AND diagnostic imaging OR specific modalities such as computed tomography, MR, ultrasound, etc.

Two authors independently cross-checked reference lists for additional relevant articles.

To avoid publication biases, as the articles spanned about two decades and the availability of the imaging modalities varied over the years, we plotted the selected studies onto a funnel plot. This graph was roughly symmetrical and thus publication bias was not present.

Eligibility criteria

Initial criteria for inclusion of studies in the systematic review were original articles aiming to describe the frequency of incidental findings in clinical practice in the imaging diagnostic field published until 31 December 2007. Language was restricted to English.

To appraise the quality of primary studies, we used the quality assessment tool named QUADAS [5]. We selected those articles fulfilling more than seven items.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted the following data: study design (observational retrospective or prospective and medical record review); study sample size; type of imaging test carried out: (a) CT; (b) radiographs; (c) other techniques, including MRI, ultrasonography and positron emission tomography (PET) and (d) a combination of more than one technique, for instance CT/PET; initial diagnosis grouped in different categories, mainly based on the 10th Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD-10): (a) neoplasm, (b) diseases of the genitourinary and digestive system, (c) mental and behavioural disorders, diseases of the nervous system and diseases of the senses, diseases of the circulatory system and endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, (d) diseases of the respiratory system, (e) diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue and (f) no specification (categories b–f do not include neoplasms); location of the incidental finding: (a) unspecified location (findings out with the organ under study without a specific localisation; for example, extra-urinary findings), (b) abdomen, (c) musculoskeletal system, skin and head-neck, and (d) chest and breast; characteristics of the incidental finding, according to the classification shown in Table 1 (studies describing, for example, “extracolonic findings” were classified of “major importance” because they included several types of abnormalities with both important and unimportant consequences); number of incidental findings; percentage of patients with complete clinical follow-up; percentage of patients with clinical confirmation of the incidental finding; and main authors' conclusions.

Table 1. Classification of the incidental findings detected according to their clinical importance: major, moderate and minor.

| Major | Moderate | Minor |

| Malignant or premalignant tumours | ||

| Head–chest | Head–chest | Head–chest |

| Parietal meningioma | Chiari malformation | Hürthle cell adenoma |

| Orbital mass | Circle of Willis calcifications | Arachnoid cyst |

| Parotid mass | Mastoiditis | Large cisterna magna |

| Severe foraminal stenosis | Thyroid incidentalomas | Follicular adenoma |

| Parathyroid adenoma | ||

| Vascular | Vascular | Vascular |

| Aortic aneurysm | Pulmonary artery dilatation | Left-sided vena cava |

| Thoracic aneurysm | Signs of portal venous hypertension | Retroaortic left renal vein |

| Iliac artery aneurysm | Atherosclerosis | Vascular graft |

| Thrombus | Hepatic or vertebral haemangioma | |

| Common femoral artery pseudoaneurysm | Abdominal aortic ectasia | |

| Dissecting aorta | Coronary artery calcification | |

| Iliac artery ectasia | ||

| Rectus muscle haemangioma | ||

| Reticuloendothelial | Reticuloendothelial | Reticuloendothelial |

| Lymphadenopathy | Splenomegaly | Splenic cyst |

| Abdominal lymph node >1 cm | Abdominal lymph node <1 cm | |

| Hepatobiliary | Hepatobiliary | Hepatobiliary |

| Solid hepatic mass | Common bile duct dilatation | Calcified hepatic or splenic granulomas |

| Solid pancreatic mass | Gallstone | Cholelithiasis |

| Indeterminate liver lesion ≥1 cm | Hepatomegaly | Hepatic cysts |

| Indeterminate pancreatic lesion ≥1 cm | Indeterminate hepatic lesion | Hepatic steatosis |

| Liver cirrhosis | Pancreatic head cyst | |

| Pancreatic calcifications | Small perihepatic fluid collection | |

| Pancreatic mass | Indeterminate liver lesion <1 cm | |

| Pancreatitis | Hepatic haemangioma | |

| Mild pancreatic duct dilatation | ||

| Gynaecological | Gynaecological | Gynaecological |

| Ovarian teratoma | Breast nodule | Simple ovarian cyst |

| Complex ovarian or adnexal cyst | Uterine enlargement | Uterine fibroids |

| Post-menopausal endometrial thickening | Uterine calcifications | |

| Bartholin's cysts | ||

| Musculoskeletal | Musculoskeletal | Musculoskeletal |

| Vertebral body deformation suspected destruction | Pigmented villonodular synovitis | |

| Lytic bone lesion | Spondylolisthesis | |

| Indeterminate sclerotic bone lesion | Degenerative spine changes | |

| Diffuse osteopenia | ||

| Sclerotic bone lesion, likely bone island | ||

| Spina bifida occulta | ||

| Osteoarthritis | ||

| Peritoneal cavity | Peritoneal cavity | Peritoneal cavity |

| Appendicitis | Abdominal wall hernia | Appendiceal stone |

| Indeterminate retroperitoneal masses | Pelvic fluid collection | Umbilical hernia |

| Pelvic mass | Hiatal, ventral, umbilical, or Bochdalek's hernia | |

| Ascites | ||

| Indeterminate soft-tissue mass in abdominal wall | ||

| Ileal wall thickening | ||

| Renoadrenal | Renoadrenal | Renoadrenal |

| Adrenal mass with indeterminate appearance | Adrenal adenoma | Adrenal myelolipoma |

| Hydronephrosis with marked parenchymal reduction | Adrenal mass with benign appearance | Bladder diverticulum |

| Renal mass | Hydronephrosis | Bladder stone |

| Severe bilateral renal parenchymal reduction | Indeterminate adrenal nodule | Gallbladder absent or not seen |

| Suspected undescended testis | Prostate enlargement | Mild renal parenchymal reduction |

| Gallbladder wall thickening | Renal angiomyolipoma | Renal atrophy |

| Soft-tissue density within the gallbladder | Renal parenchymal reduction | Renal calculi |

| Solitary kidney | Renal cyst | |

| Pyelonephritis | Renal malrotation | |

| Urethra–pelvic junction obstruction | Small renal calcifications | |

| Bladder outlet obstruction | Suspected renal stones | |

| Complex renal cyst | Suspected ureteric stone | |

| Scrotal hydrocoele | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract | Gastrointestinal tract | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Bowel obstruction | Hyperplastic colonic polyp | Hiatal hernia |

| Gastric mass | Bowel inflammation | Diaphragmatic hernia |

| Terminal ileum mass or thickening | Diverticulosis | Focal gastritis |

| Bowel wall thickening | Inguinal hernia or bowel-containing abdominal hernia | Gastric fundus diverticulum |

| Rectal inflammation and/or haemorrhoids | ||

| Thoracic cavity | Thoracic cavity | Thoracic cavity |

| Cardiomegaly | Bronchiectasis | Calcified pulmonary nodules |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Pericardial effusion | Pleural plaques |

| Pneumothorax | Pneumobilia | Subcutaneous emphysema |

| Pulmonary embolism | Pulmonary nodules | Lung base subsegmental atelectasis, scarring, and dependent changes |

| Pulmonary parenchymal opacity | Diaphragmatic calcification | |

| Consolidation and infiltrates | Cystic lung lesion | |

| Interstitial lung disease | Pericardial granuloma | |

| Pleural fluid | ||

| Pulmonary emphysematous bullae | ||

| Mitral annulus calcifications | ||

| Tracheomalacia | ||

| Others | ||

| Splenic, pulmonary, hepatic or adrenal granuloma | ||

| Lipoma | ||

| Findings in orthodontic panoramic radiographs: radio-opacities, thickening of mucosal lining in sinus, periapical inflammatory lesion, dentigerous cyst, cyst within alveolar bone, odontoma, altered tooth morphology, marginal bone loss |

The authors independently checked all of the extracted data against the publications twice, to ensure correct and complete data extraction. Any discrepancies in extracted data were discussed, and disagreements were resolved by consensus with the third author.

Statistical analysis

Some variables were grouped owing to limited data for analysis. These include MRI, ultrasound and PET in the variable “technique”; genitourinary and gastrointestinal system and central nervous, circulatory and endocrine system in the variable “initial diagnosis”; and musculoskeletal system, skin and head–neck in the variable “location”.

Study characteristics were summarised as means and their 95% confidence interval (CI) or frequencies and proportions. The relationship between the main variables of interest (frequency of incidental findings, frequency of follow-up and frequency of confirmation) and the study characteristics was assessed by one-way ANOVA test. We considered variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 to be significant. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 15.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Literature search

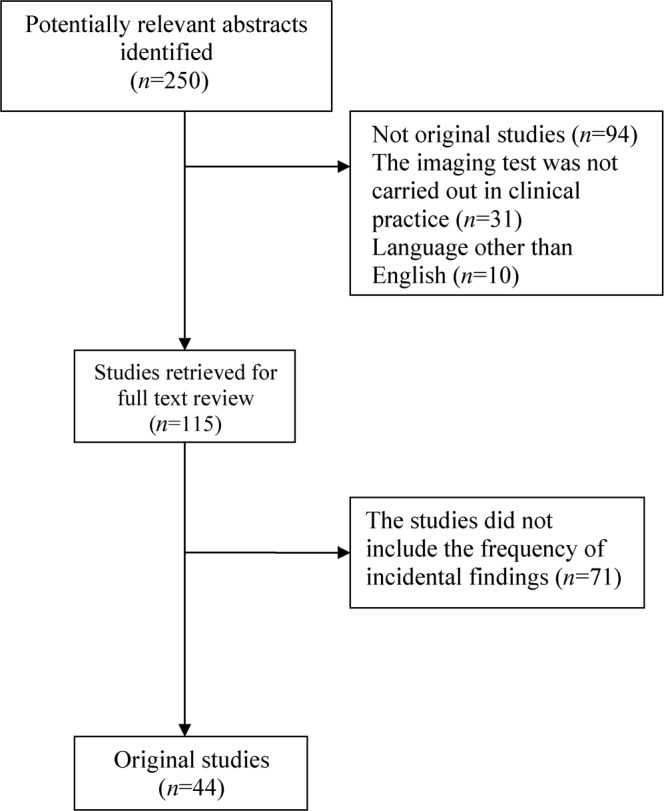

We identified 251 potentially relevant abstracts; (Figure 1) of these, 89 articles were retrieved for full text review and finally 44 articles were included in the systematic review [6–49]. (The characteristics of these 44 reviewed articles are listed in Annex 1.)

Figure 1.

Description of the literature search.

Annex 1. Description of the 44 studies, including data of unexpected finding frequency.

| Study, year, reference | Type of study | Techniques evaluated | Initial diagnosis | Sample | Incidental finding | Finding classification | Finding frequency | Follow-up | Clinical confirmation | Conclusions |

| Bogsrud et al 2007 [6] | Medical record review | 18F-FDG-PET/CT | Study of oncology imaging | 7347 patients | Abnormal FDG uptake | Moderate importance | 79/7347 (1.1%) | 48/79 (60.1%) patients were followed up | Confirmation in 46 (95.8%) patients: 31 as benign and 15 patients as malignant. | Incidental finding of a nodule with high FDG uptake in thyroid gland should always be reported as primary or secondary malignancy and further evaluation should be recommended |

| Are et al 2007 [7] | Experimental prospective | 18F-FDG-PET | Patients with primary malignancies | 8800 patients | Thyroid abnormality | Moderate importance | 263/8800 (2.9%) | 57 (21.7%) patients were followed up | 21 pathologies were confirmed (7.9%) | Prevalence of incidentalomas is low, but focal uptakes remain high among this group and requires an operative intervention and fine needle aspiration cytology |

| Ritchie et al 2007 [8] | Experimental prospective | Multidetector CT | Inpatients undergoing scanning of the chest for an indication other than suspected pulmonary embolism | 487 patients | Pulmonary embolism | Major importance | 28/487 (5.7%) | No | No | There is a high prevalence of unsuspected pulmonary embolism. The incidence increases with age and there is no statistical correlation with length of admission or associated malignancy |

| Khan et al 2007 [9] | Experimental prospective | CT colonography | Suspected or known colorectal cancer | 225 patients | Extracolonic findings | Major importance | 116/225 (51.5%) | 104 (89%) were selected for follow up: outpatient appointments, radiological tests and surgical procedures | 24 (21%) cases were confirmed | Frequency of extracolonic findings increased with age and most of them are insignificant. Guidelines can avoid unnecessary tests |

| Wang et al 2007 [10] | Experimental prospective | PET/CT | Known or suspected cancer | 1727 patients | Any focal extrathyroidal accumulation of FDG | Major importance | 199/1727 (12%) | 181/199 (91%) follow-up by PET and CT | 59 (33%) were confirmed as malignancies. | Most findings were benign. Experienced readers of whole-body FDG-PET/CT can avoid unnecessary investigations, reducing cost and patient anxiety |

| Paluska et al 2007 [11] | Medical record review | CT | Patients who received at least one spiral CT in trauma department | 848 patients | Cyst, masses, calcifications, nodes, embolism, thrombosis | Moderate importance | 289/848 (34%) | Follow-up in 2 weeks: 108 (12.7%) | Clinical confirmation: 15 (1.7%) | Incidental findings are more common in women and older patients. An organised approach is essential to deal with them |

| Vierikko et al 2007 [12] | Experimental prospective | Chest radiography, spiral CT and high-resolution CT | Asbestos-exposed workers | 633 patients | Non-calcified lung nodules | Moderate importance | 277/633 (44%) | 46 (16.6%) patients were submitted for further investigations | 4 (1.4%) were judged as clinically important | Spiral CT and even high-resolution CT is more useful to screening for lung cancer than chest radiography in asbestos-exposed workers |

| Koos et al 2006 [13] | Experimental retrospective | CT echocardiography | Patient underwent multidetector CT of the chest | 402 patients | Aortic valve calcification | Moderate importance | 72/402 (18%) | Follow-up in 100% patients | Confirmation of aortic stenosis in 21/72 (29%) patients. | Aortic valve calcification, a common finding, predicts the grade of calcification, which is correlated with moderate or severe aortic valve disease |

| Belfi et al 2006 [14] | Experimental retrospective | CT | Abdominal pain and fever | 510 patients | Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis | Minor importance | 29/510 (5.7%) cases of spondylolysis at L5 | Follow-up 100% by a neuroradiologist | Confirmation in 100% of patients. | The high prevalence of spondylolysis as an unrelated finding reminds clinicians to be aware when they perform CT |

| Choksi et al 2006 [15] | Experimental retrospective | Radiograph, sonography, CT, MRI, urography, myelography, angiography | NA | 37736 radiology examinations | Suspected malignancy | Major importance | 395/37736 (1%) | In 351/395 (88.8%) patients further investigation was carried out | 188 (47.6%) cases were malignant | The authors developed a system to ensure that incidental findings received adequate care |

| Xiong et al 2006 [16] | Medical record review | CT colonography | Diagnosis of colorectal cancer | 225 patients | Extracolonic findings | Major importance | 116/225 (53%) | All patients were followed (100%) | Confirmation in 24 patients (20.7%). | Resources consumed by an extracolonic finding approximately doubled the cost of diagnostic CTC |

| Morris et al 2006 [17] | Medical record review | Radiograph thorax | NA | 10291 patients | Vertebral fractures | Major importance | Patients with incidental vertebral fracture: 142 (1.4%) | No | No | Fracture documentation was associated with an increased likelihood of starting an osteoporosis medication. It is important to value these findings to improve osteoporosis management |

| Even-Sapir et al 2006 [18] | Experimental prospective | PET/CT | Known or suspected cancer | 2360 patients | Malignancy | Major importance | 151/2360 (6.4%) | 115 (76.2%) patients were followed up | 41(27.2%) malignancies were confirmed | Combination of PET and CT increases probability to define correctly incidental tumours |

| Shetty et al 2006 [19] | Medical record review | Thoracic and cervical CT | NA | NA | Abnormality in the thyroid gland | Moderate importance | 230 patients | Follow-up: 100% (with thyroid sonography) | Confirmation of malignancy in 11.3%. | Sonography is a useful adjunctive test after the incidental detection of a thyroid abnormality on CT |

| Sebastian et al 2006 [20] | Experimental prospective | Chest CT | Patients with malignancy | 385 patients | Pulmonary embolism | Major importance | 10/385 (2.6%) | Follow-up in 2 (20%) patients | Confirmation in 2 (20%) patients | Formal review of pulmonary arteries during chest CT review in oncology patients is recommended |

| Bondemark et al 2006 [21] | Experimental prospective | Orthodontic panoramic radiographs | Patients randomly selected from an orthodontic clinic | 496 patients | Orthodontic abnormalities | Minor importance | 43/496 (8.7%) | No | No | The clinician should be aware of the potential to detect pathology and abnormality in pre-treatment orthodontic panoramic radiographs |

| Bruzzi et al 2006 [22] | Medical record review | PET/CT | Patients with non-small cell lung cancer | 321 patients | Abnormalities without abnormally increased 18F-FDG uptake | Minor importance | 1231 abnormalities in 263 patients (82%) | No | No | Among patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing PET/CT, there is a high prevalence of CT abnormalities that may be clinically important |

| Bovio et al 2006 [23] | Experimental prospective | CT | Screening programme of lung cancer | 520patients | Adrenal masses | Moderate importance | 23/520 (4.4%) | Follow-up in all the patients | Clinical confirmation in all the patients | Adrenal masses incidentally detected during CT scans are increasing. Definition of prevalence is a necessary requisite to achieve management strategies |

| Onuma et al 2006 [24] | Experimental prospective | Multidetector CT | Suspected coronary artery disease | 503 patients | Non-cardiac findings | Major importance | 292 (58.1%) patients. | 114 (22.7%) patients with clinical or radiological follow-up | A total of 114 patients (22.7%) had clinically significant findings | Owing to the high number of non-cardiac findings by multidetector CT, cardiologists and radiologists should work together to define them accurately |

| Weber et al 2006 [25] | Experimental prospective | MRI | Routine medical screening | 2536patients | Intracranial abnormalities: tumours, arachnoid cysts, vascular abnormalities | Major importance | 166/2536 (6.5%) | 1 (0.6%) patient had further work-up | Confirmation in 1 (0.6%) of the patients | Only a small percentage of the small abnormalities detected require urgent medical attention |

| Osman et al 2005 [26] | Experimental prospective | Unenhanced CT, PET, CT | Known or suspected cancer | 250 patients | Renal mass, liver cirrhosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, kidney lesion, sclerotic bone metastasis | Major importance | 7/250 (3%) | 4 (57.0%) patients underwent a PET/CT follow | Confirmation in 4 (57.0%) cases | Findings need to be analysed to prevent alterations in clinical management of these patients |

| Eskandary et al 2005 [27] | Experimental prospective | Brain CT | Multiple traumas | 3000 patients | Bone lesion, calcification, arachnoid cyst | Minor importance | 30/3000 (1%) | Follow-up in 100% patients | Confirmation in 100% patients | Prevalence of some incidental findings in head-injured patients detected by brain CT scans could be considered as representative of the general population |

| Liu et al 2005 [28] | Experimental prospective | CT urography | Haematuria | 344 patients | Extraurinary findings | Major importance | 259/344 (75.3 %) | 39 (15.1%) patients had follow-up | Confirmation of high importance of 20 (7.7%) findings | Detecting extraurinary findings may be important because significant morbidity and mortality may be prevented |

| Israel et al 2005 [29] | Medical record review | PET/CT | Known or suspected malignancy | 4390 patients | Focally increased 18F-FDG uptake | Major importance | 58/4390 (1.3%) | Follow-up in 34 (59%) patients | 11 (32%) patients were confirmed as having malignant tumours | Incidental focal 18F-FDG uptake is significant in most patients. Adequate follow-up with invasive procedures and imaging results is necessary to determine malignancy of those diseases |

| Ishimori et al 2005 [30] | Medical record review | 18F-FDG-PET/CT | Known or suspected primary malignant lesions | 1912 patients | New primary malignant lesions | Major importance | 79/1912 (4.1%) | Follow-up in 40 (51%) patients | 22 (27.8%) patients were pathologically confirmed | Besides the presence of false-positive results, the newly detected lesions have an excellent probability of cure because of their early stage |

| Majumdar et al 2005 [31] | Medical record review | Chest radiography | Chest radiography evaluation in emergency department | 459 patients | Moderate to severe vertebral fractures | Major importance | 72/459 (16%) | Follow-up in all patients | Findings were confirmed in 24% patients | As the population ages, the prevalence of osteoporosis is going to increase; it is essential to implement case-finding strategies for elderly people |

| Ares Valdés et al 2005 [32] | Experimental retrospective | Ultrasound, CT | Gastrointestinal symptoms | 30 patients | Renal cell carcinoma | Major importance | 6/30 (20%) cases | All patients were submitted to surgery, treatment and follow-up 60–120 months | Confirmation in 100% of the cases | Incidental renal cell carcinoma has a low incidence; conservative surgery is applied for incidental small renal masses and radical surgery is used for masses with large dimensions |

| Yee et al 2005 [33] | Experimental prospective | CT colonography | Colorectal cancer screening | 500 patients | Extracolonic findings | Major importance | 315/500 (63%) | Follow-up in 35 (31%) patients | 13 (4.1%) findings were confirmed as clinically important | A substantial number of both average- and high-risk patients had extracolonic findings. Cost for work-up is low and does not increase patients' morbidity and mortality |

| Campbell et al 2005 [34] | Experimental prospective | Chest CT | Routine departmental protocol in patients with benign, indeterminate or malignant disease | 148 patients | Extrapulmonary findings | Major importance | 31/148 (20.9%) | No | No | Reports of incidental findings in patients with non-malignant disease do not add any relevant information |

| Ng et al 2004 [35] | Experimental prospective | Abdominopelvic CT | Suspicious colorectal carcinoma | 1031 patients (1077 cases) | Extracolonic findings | Major importance | 261/1077 (24%) | 344 findings: 156 (45%) underwent follow-up | 133 (85%) cases were confirmed | Extracolonic findings detected on CT scans may help in staging colorectal cancer |

| Agress et al 2004 [36] | Experimental prospective | 18F-FDG PET | Known or suspected cancer | 1750 patients | Unusual hypermetabolism localisation | Major importance | 53/1750 (3%) | 45 (85%) patients were followed up with CT, MRI | 30 (71%) were either malignant or premalignant tumours; 9 proved benign and 3 represented false-positive findings | Results of this study emphasise the need for follow-up of these abnormalities because the majority represent either malignant or premalignant neoplasms |

| Kang et al 2004 [37] | Medical record review | Ultrasound | Patients referred for evaluation of thyroid gland | 1475 patients | Thyroid nodules | Moderate importance | 198/1475 (13.4%) | Follow-up: 100% | Confirmation of malignancy in 57 (28.8%) patients. | Occult thyroid cancers are a fairly common finding with ultrasonography. They can be used in the decision about optimal management strategies |

| Schragin et al 2004 [38] | Experimental retrospective | Electron beam CT | Patients with a routine cardiac EBT scanning | 1356 patients | Non-cardiac abnormalities | Major importance | 278/1356 (20.5%) | Follow-up with CT in 57 (20.5%) of the patients | Confirmation by passive follow-up in all patients | With the relatively high detection of significant non-cardiac pathology in EBT, consideration should be given for radiologists to interpret the scans |

| Hellstrom et al 2004 [39] | Experimental prospective | CT colonography | Patients with known or suspected colorectal disease | 111 patients | Extracolonic findings | Major importance | Moderate or major findings in 65 (58.6%) patients | Follow-up in 61 (97%) of the patients | Confirmation in 14 (13%) patients | The presence of unexpected findings must be taken into account when CT colonography is considered for routine diagnostic work-up or screening |

| Ginnerup Pedersen et al 2003 [40] | Experimental prospective | Multidetector CT colonography | Surveillance for former colorectal cancer or large bowel adenoma | 75 patients | Extracolonic abnormalities | Major importance | 49/75 (65%) | 8 (12%) patients with additional work-up | Confirmation of the pathologies in the 8 (12%) patients | High prevalence of incidental findings makes multidetector CT a problematic screening tool. The authors emphasise the need for patients to be informed of the possibility of incidental findings and consequent additional work-up |

| Cai et al 2003 [41] | Experimental prospective | CT | Gastrointestinal disease | 12021 patients | Thickened distal oesophagus, caecum, sigmoid colon or rectum | Major importance | 117/12021 (1%). | 67 (57.3%) had documented further endoscopic examination | 81% of patients with thickening of the distal oesophagus, and 13% of patients with thickening of the caecum confirmed the abnormalities | Incidental findings of thickened luminal gastrointestinal organs on CT are not uncommon and warrant further endoscopic examination to determine significant abnormalities |

| Fitzgerald et al 2003 [42] | Experimental prospective | Ultrasound, MRI and CT | Pelvic pain, breast cancer staging, renal colic, vaginal bleeding | 53 patients | Pancreatic masses | Major importance | 7/53 (13.2%) | Follow-up in 100% patients | The diagnosis was confirmed in 7 (100%) patients | The identification of pancreatic incidentalomas appears to be increasing secondary to the broad application of high-resolution imaging |

| Hasegawa et al 2003 [43] | Experimental retrospective | CT pulmonary angiography | Suspected pulmonary embolism | 163 patients | Tracheomalacia | Moderate importance | 16/163 (10%) | No | No | Tracheomalacia is a relatively common incidental finding. Physicians must be careful reviewing central airways and pulmonary vasculature in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism |

| Ahmad et al 2003 [44] | Medical record review | Unenhanced helical CT | Flank pain suggestive of renal/ureteric colic | 233 patients | Extrarenal/uteric findings | Major importance | 28/233 (12%) | 20/28 (71%) were followed up by surgical procedures, biochemical or biopsy evaluation | 20/28 (71%) findings were confirmed | A wide variety of significant alternative or additional diagnoses can be reliably identified on unenhanced helical CT for suspected renal/ureteric colic |

| Brown et al 2001 [45] | Medical record review | MRI | Patients referred for equivocal mammographic findings | 103 patients | Focal enhancing lesions on breast | Moderate importance | 30/103 (29%) | Follow-up in 29 (96.6%) patients | Cancer confirmation in 1 (3.3%) patient | Focal enhancing lesions are unlikely to be malignant |

| Völk et al 2001 [46] | Experimental prospective | Contrast-enhanced hepatic spiral CT | NA | 100 patients | Benign hepatic lesions | Minor importance | 33/100 (33%) | 21 (63.6%) patients were followed up with CT studies, MRI and percutaneous ultrasound | 21 (63.6%) cases were confirmed | Benign hepatic lesions are relatively common on portal venous phase spiral CT |

| Messersmith et al 2001 [47] | Medical record review | Abdominal CT | Suspected nephrolithiasis | 307 patients | Hiatal hernia, renal cysts, fatty liver, small pericardial effusion, ovarian mass, hepatic mass | Moderate importance | 145/307 (47%) | 11 (7.6%) cases were followed up with abdominal CT | Confirmation of all findings that none yield any serious disease | An incidental finding in CT scans done in the Emergency Department due to renal colic has a high rate, but the follow-up rate is low. Lack of resources does not allow further investigations |

| Weder et al 1998 [48] | Experimental prospective | Whole body FDG-PET | Evaluation of non-small cell lung cancer patients | 100 patients | Extrathoracic metastases | Major importance | 19/100 (19%) | All findings were followed up | Confirmation 100% histologically or radiologically | Whole body FDG-PET is an excellent method to detect extrathoracic metastasis |

| Iko 1986 [49] | Experimental prospective | Colangiography, ultrasound, CT | NA | 107 patients | 6 bilomas, 3 aberrant bile ducts, 3 hepatic and 3 subphrenic abscesses and 2 gastrobiliary fistulae | Moderate importance | 17/107 (16%) | Follow-up in 100% patients | Confirmation in 100% patients | Cross-sectional imaging will clarify situations where confusing accumulations occur in cholangiography |

CI, confidence interval; CTC, computed tomography colonography; EBT, electron beam tomography; 18F-FDG-PET, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; PET, positron emission tomography.

Description of the studies

The 44 original reports were published between 1986 and 2007 (Table 2). The main imaging techniques carried out were CT in 26 studies (59%), combination of more than one technique in 8 studies (18%), other techniques such as MRI, ultrasound and PET in 7 papers (16%), and radiographs in 3 articles (7%). The most frequently described diagnosis was neoplasm (18; 41%) followed by diseases of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal system (7; 16%). The median sample size was 496 (interquartile range (IQR) 225–1750) and mean frequency of incidental findings was 23.6 (95% CI 15.8–31.3). Most papers described incidental findings with an unspecified localisation (15; 34%) or abnormalities located in abdomen (13; 30%).

Table 2. Description of the 44 original studies analysed in the systematic review and their main characteristics according to the mean of incidental findings.

| Variablesa,b | Original studies (n, %) | Finding frequency (mean; 95% CI) |

| Technique | ||

| CT | 26 (59) | 31.1 (20.1–41.9) |

| More than one technique | 8 (18) | 13.9 (0–37.1) |

| Other (MRI, ultrasound, PET) | 7 (16) | 13.4 (4.3–22.5) |

| Radiograph | 3 (7) | 8.7 (0–26.8) |

| Year | ||

| 1986–2004 | 15 (34) | 24.3 (13.7–34.9) |

| 2005–2007 | 29 (66) | 23.2 (12.4–34.1) |

| Type of study | ||

| Observational prospective | 23 (52) | 21.3 (11.0–31.6) |

| Medical record review | 14 (32) | 29.7 (11.8–47.5) |

| Observational retrospective | 7 (16) | 19.1 (1.6–36.6) |

| Initial diagnosis | ||

| Neoplasm | 18 (41) | 27.1 (13.3–40.8) |

| Genitourinary + gastrointestinal system | 7 (16) | 24.9 (0.1–40.6) |

| Nervous central + circulatory + endocrine system | 7 (16) | 21.6 (4.6–38.6) |

| Unspecific localisation | 5 (11) | 30.5 (0–81.6) |

| Respiratory system | 4 (9) | 11.9 (3.5–20.3) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 3 (7) | 8.6 (0–27.2) |

| Location | ||

| Unspecific localisation | 15 (34) | 33.9 (18.1–49.7) |

| Abdomen | 13 (30) | 22.6 (10.2–34.9) |

| Musculoskeletal system and skin, head–neck | 10 (23) | 15.7 (0–37.2) |

| Chest and breast | 6 (14) | 13.2 (3.2–23.2) |

| Study size | ||

| <496 | 22 (50) | 29.9 (19.2–40.8) |

| ≥496 | 22 (50) | 17.2 (5.9–28.5) |

| Total | 44 (100) | 23.6 (15.8–31.3) |

aOne-way ANOVA. t-test.

CI, confidence interval; PET, positron emission tomography.

Description of original papers in relation to frequency of incidental findings

Smaller studies (those with a sample size under the median 496) reported a higher frequency of incidental findings (mean 29.9, 95% CI 19.2–40.8) than larger studies (mean 17.2, 95% CI 5.9–28.5) (Table 2). The rest of the analysed variables did not show any significant differences related to finding frequency. The frequency of incidental findings was higher in studies involving CT technology (mean 31.1, 95% CI 20.1–41.9) or patients with a non-specific initial diagnosis (mean 30.5, 95% CI 0–81.6) or when the location of the incidental findings was unspecified (mean 33.9, 95% CI 18.1–49.7).

Most studies included findings considered of major importance (27; 61.4%), whereas 12 (27.3%) evaluated findings of moderate significance, and five (11.4%) showed abnormalities of minor importance. Studies were more likely to include findings of major importance when the initial diagnosis was neoplasm (14; 51.9%), and findings of minor consequences were more likely to be presented when the initial diagnosis was related to the musculoskeletal system (2; 40.0%) (p = 0.019). Localisation of the findings was also related to the characteristics of the findings: findings in musculoskeletal system, skin, and head and neck were more likely to be of minor importance (3 studies; 60%) than the other localisations (p = 0.023) (data not shown).

Description of original papers according to the frequency of clinical follow-up and clinical confirmation

Out of 44 studies, 11 (25%) carried out clinical follow-up of all the unexpected findings reported and 27 (61%) studies performed work-up of only some of them (Table 3). The mean frequency of clinical follow-up was 64.5% (95% CI 52.9–76.1%). No differences between the studied variables and the mean clinical follow-up were shown. Nevertheless, studies involving patients with unspecific initial diagnosis (mean 75.4, 95% CI 8.4–100.0) and unexpected abnormalities located in the musculoskeletal system, the skin, head or neck constitute the higher frequency of clinical work-up.

Table 3. Description of the clinical follow-up and clinical confirmation of the diagnosis in the 44 original studies analysed in the systematic review according to their main characteristics evaluated.

| Variablea,b | % Clinical follow-up (mean, 95% CI) | % Clinical confirmation (mean, 95% CI) |

| Technique | ||

| CT | 60.0 (43.5–76.5) | 48.7 (27.2–70.2) |

| More than one technique | 69.8 (54.0–84.0) | 45.8 (22.9–68.6) |

| Other (MRI, ultrasound, PET) | 69.0 (31.0–100) | 41.1 (0.9–81.2) |

| Radiograph | 100 (–) | 24.0 (–) |

| Year | ||

| 1986–2004 | 67.2 (47.2–87.1) | 61.2 (34.9–87.4) |

| 2005–2007 | 63.0 (47.6–78.4) | 38.6 (22.4–54.8) |

| Type of study | ||

| Observational prospective | 56.6 (40.4–72.7) | 50.3 (29.5–71.1) |

| Medical record review | 68.9 (45.6–92.2) | 31.6 (10.3–52.9) |

| Observational retrospective | 84.4 (51.2–100) | 57.9 (7.9–100) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Neoplasm | 65.9 (51.4–80.5) | 48.4 (30.0–66.8) |

| Genitourinary + gastrointestinal system | 64.4 (27.5–100) | 75.7 (26.0–100) |

| Nervous central + circulatory + endocrine system | 43.9 (0–88.9) | 10.2 (0–30.5) |

| Unspecific localisation | 75.4 (8.3–100) | 40.2 (0–100) |

| Respiratory system | 58.3 (0–100) | 15.2 (0–100) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 100 (–) | 62.0 (0–100) |

| Locationb | ||

| Abdomen | 69.5 (48.8–90.1) | 77.4 (64.5–100) |

| Unspecific localisation | 57.4 (37.9–76.8) | 34.9 (15.2–50.1) |

| Musculoskeletal system and skin, head–neck | 72.8 (38.6–100) | 46.1 (8.9–83.2) |

| Chest and breast | 58.3 (0–100) | 13.4 (0–34.6) |

| Study size | ||

| <496 | 72.3 (53.6–90.9) | 50.7 (28.6–72.7) |

| ≥496 | 58.3 (42.7–73.8) | 41.7 (22.9–60.5) |

| Total | 64.5 (52.9–76.1) | 45.6 (32. –59.2) |

aOne-way ANOVA. t-test.

bp-value: 0.014 for the variable “% clinical confirmation”.

CI, confidence interval; PET, positron emission tomography.

Findings of minor importance (mean 87.9, 95% CI 64.0–111.6) were more likely to be followed up than those of major (mean 61.4, 95% CI 47.9–74.9) or moderate (mean 65.0, 95% CI 40.4–89.7) consequences, but the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.485) (data not shown).

With regard to clinical confirmation, 11 (25.0%) studies did not verify any of the unexpected findings: 8 (18.2%) articles confirmed the clinical significance of all the abnormalities and 25 (56.8%) confirmed some of them. The mean frequency of clinical confirmation was 45.6% (95% CI 32.1–59.2). Unexpected findings located in the abdomen showed the highest frequency of clinical confirmation (mean 77.4, 95% CI 54.5–100.0) in comparison with other locations such as the musculoskeletal system, the skin, head or neck (mean 46.1, 95% CI 8.9–83.2), chest or breast (mean 13.4, 95% CI 0.0–34.6) or unspecified location (mean 34.9, 95% CI 15.2–54.7) (p = 0.014).

Findings of minor importance (mean 87.9, 95% CI 64.0–111.6) were more likely to be confirmed than those of major (mean 43.0, 95% CI 11.2–64.6) or moderate (mean 37.9, 95% CI 40.4–89.7) importance, but the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.114) (data not shown).

Discussion

In an effort to determine the frequency and variables related to incidental findings in imaging tests, we systematically reviewed the literature. As we expected, the higher frequency of incidental findings was observed in studies involving CT, but there were no differences with respect to other imaging techniques. The wider field of view of CT has led to better visualisation of organs and tissues and, therefore, a higher probability of encountering additional findings. We were unable to establish the difference between various types of CT (CT colonography, multidetector CT, etc.) owing to the relatively small number of studies focusing on unexpected findings.

An important percentage of the patients in whom unexpected findings were observed underwent further evaluation with more imaging tests or other diagnostic tests and procedures. Although the mean frequency of clinical confirmation was high for findings of minor importance, it was lower for abnormalities of major or moderate importance. The difficulty is in distinguishing between those findings that can be characterised without additional imaging and those that can be ignored or those that may need additional follow-up [50].

In this paper, we have tried to classify the possible unexpected findings in three different groups according to their clinical relevance: major, moderate and minor. This classification of severity could be open to question and we cannot consider this classification as a strict rule to manage these abnormalities; it can be used only as a support aid to make the diagnostic work-up easier. We tried to classify the findings according to the most common situations in practice. However, depending on each particular patient, an incidental finding could be considered as major, minor or of non-pathological importance. For example, the definition of osteoarthritis as an incidental abnormality is age related. We could assume that some results are biased because of this classification, but the categorisation of a particular unexpected abnormality would not have a great influence on the global result.

In this study, we have also shown that incidental findings of major importance were more likely in patients with the initial diagnosis of neoplasm than, for instance, in patients with an initial diagnosis related to the musculoskeletal system.

The role of the radiologist is crucial in deciding whether an image feature is normal or a potentially important diagnostic discovery. Nevertheless, with a different perspective, the incidental finding is also a problem for clinicians, and the collaboration between radiologists and clinicians is essential to deal with these abnormalities [51].

The critical question concerning incidental findings is not only whether they should be reported, but also how often they occur and what is their effect economically and clinically. However, there are few studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of incidental findings. In the analysis of incidental extra-urinary findings with multidetector CT (MDCT) urography [28], the authors evaluated the impact on subsequent imaging costs. In this case, only a small percentage of patients were imaged further and, hence, detecting extra-urinary disease did not mean a substantial increase in per-patient imaging costs. Another study [16] was performed to assess the clinical resources and costs associated with the investigation and treatment of extracolonic lesions when using CT colonography. In this research, however, resources consumed as a result of extracolonic findings approximately doubled the costs of diagnostic computer tomography colonography (CTC).

Unfortunately, many radiologists are rarely consulted and they perform and interpret the imaging reports without patients' clinical information [52]. In fact, most of the studies in this review separately involved either radiologists or clinicians. Nevertheless, in one study [24] the high number of non-cardiac findings detected by MDCT caused the authors to recommend close co-operation between cardiologists and radiologists in defining these more accurately. Each radiologist and clinician should try to balance the potential to diagnose a disease that may cause morbidity and mortality against unnecessary testing and treatment, which carry their own risks together with patient anxiety and the cost to society. The discussion is made especially complex by the absence of professional guidelines. Some recommendations, however, have been described in an attempt to clarify the situation [53]. The recommendations include, among others things, factors such as the assessment of the potential risk of the incidental finding for the patient or the availability of a beneficial treatment that justifies follow-up of the abnormality. However, the optimal strategy for evaluation of a patient with an unexpected finding discovered is unclear and remains controversial. The ideal study to resolve these controversies would be a prospective multicentre randomised (or even non-randomised) trial. However, we lack such a study. This review of the literature includes a broad spectrum of unexpected findings detected by different techniques and with several consequences. Even though future studies are needed to evaluate the outcomes of the clinical management decisions, these data could help characterise the problem in order to establish professional guidelines.

There are some general limitations to this review, which should be kept in mind. The wide variation in detection rates for incidental lesions could be due to heterogeneity of the selected studies. Accordingly, previous studies have shown this variation in relation to the lack of standardised guidelines in the definition and management of incidental abnormalities [54]. As we mentioned previously, we did not have a sufficient sample size to establish differences in more detail, such as the specific type of imaging techniques. Moreover, this was a challenging topic for a systematic review; incidental findings are difficult to define and identify in literature searches. We tried, however, to be consistent and specific with regard to our inclusion and exclusion criteria and our data extraction methods so as to avoid omitting or including studies inappropriately. For the selection of the articles we applied QUADAS [5], designed specifically to assess the quality of primary studies included in diagnostic systematic reviews; although the outcomes of this review are not test accuracy, the methodological criteria are still applicable. During the diagnostic process, many radiologists can detect incidental findings and perform additional examinations before completing the report. For example, in the pre-operative assessment, they might carry out a CT examination after detecting an abnormality on a radiograph. These cases would be hidden to any investigation of unexpected findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have found a high percentage of incidental findings in imaging tests, especially with CT examinations and patients with non-specific initial diagnoses. Most patients with abnormalities were clinically followed up, especially those with findings of minor importance. However, only some of them were clinically confirmed. It is important to be aware of the high percentage of patients who undergo further evaluation owing to the presence of unexpected findings, but without obtaining clinical confirmation of these abnormalities.

The classification of the incidental findings we have shown in this study and the characteristics of the abnormalities with a greater probability of clinical confirmation could aid radiologists and clinicians in the management of incidental findings.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the drafting, review and revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Exp PI05/0757, Instituto de Salud Carlos III. We acknowledge partial funding and support of this research from the CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP) in Spain. We thank Jonathan Whitehead and Lucy Anne Parker for assistance in preparing the English version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Deyo R. Cascade effects of medical technology. Annu Rev Public Health 2002;23:23–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young WF. Clinical practice. The incidentally discovered adrenal mass. N Engl J Med 2007;356:601–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beigelman-Aubry C, Hill C, Grenier PA. Management of an incidentally discovered pulmonary nodule. Eur Radiol 2007;17:449–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mold JW, Stein HFC. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med 1986;314:512–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogsrud TV, Karantanis D, Nathan MA, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Collins DA, et al. The value of quantifying 18F-FDG uptake in thyroid nodules found incidentally on whole-body PET-CT. Nucl Med Commun 2007;28:373–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Are C, Hsu JF, Schoder H, Shah JP, Larson SM, Shaha AR. FDG-PET detected thyroid incidentalomas: need for further investigation? Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:239–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie G, McGurk S, McCreath C, Graham C, Murchison JT. Prospective evaluation of unsuspected PE on contrast enhanced multidetector CT scanning. Thorax 2007;62:536–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan KY, Xiong T, McCafferty I, Riley P, Ismail T, Lilford RJ, et al. Frequency and impact of extracolonic findings detected at computed tomographic colonography in symptomatic population. Br J Surg 2007;94:355–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G, Lau EW, Shakher R, Rischin D, Ware RE, Hong E, et al. How do oncologists deal with incidental abnormalities on whole-body fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT? Cancer 2007;109:117–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paluska TR, Sise MJ, Sack DI, Sise CB, Egan MC, Biondi M, et al. Incidental CT findings in trauma patients: incidence and implications for care of the injured. J Trauma 2007;62:157–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vierikko T, Järvenpää R, Autti T, Oksa P, Huuskonen M, Kaleva S, et al. Chest CT screening of asbestos-exposed workers: lung lesions and incidental findings. Eur Respir J 2007;29:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koos R, Kühl HP, Mühlenbruch G, Wildberger JE, Günther RW, Mahnken AH. Prevalence and clinical importance of aortic valve calcification detected incidentally on CT scans: comparison with echocardiography. Radiology 2006;241:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belfi L, Ortiz A, Katz D. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine 2006;31:907–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choksi VR, Marn CS, Bell Y, Carlos R. Efficiency of a semiautomated coding and review process for notification of critical findings in diagnostic imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:933–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong T, McEvoy K, Morton DG, Halligan S, Lilford RJ. Resources and costs associated with incidental extracolonic findings from CT colonography: a study in a symptomatic population. Br J Radiol 2006;79:948–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris CA, Carrino JA, Lang P, Solomon DH. Incidental vertebral fractures on chest radiographs. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:352–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Gutman M, Lievshitz G, Zuriel L, Polliack A, et al. The presentation of malignant tumors and pre-malignant lesions incidentally found on PET-CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006;33:541–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shetty SK, Maher MM, Hahn PF, Halpern EF, Aquino SL. Significance of incidental thyroid lesions detected on CT: correlation among CT, sonography, and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:1349–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sebastian AJ, Paddon AJ. Clinically unsuspected pulmonary emboli: an important secondary finding in oncology CT. Clin Radiol 2006;61:81–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bondemark L, Jeppsson M, Lindh-Ingildsen L, Rangne K. Incidental findings of pathology and abnormality in pretreatment orthodontic panoramic radiographs. Angle Orthod 2006;76:98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruzzi JF, Truong MT, Masom EM, Mawlawi O, Podoloff DA, Macapinlac HA, et al. Incidental findings on integrated PET/CT that do not accumulate 18F-FDG. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:1116–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bovio S, Cataldi A, Reimondo G, Sperone P, Novello S, Berruti A, et al. Prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in a contemporary computerized tomography series. J Endocrinol Invest 2006;29:298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onuma Y, Tanabe K, Nakazawa G, Aoki J, Nakajima H, Ibukuro K, et al. Noncardiac findings in cardiac imaging with multidetector computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:402–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber F, Knopf H. Incidental findings in magnetic resonance imaging of the brains of healthy young men. J Neurol Sci 2006;240:81–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osman MM, Cohade C, Fishman EK, Wahl RL. Clinically significant incidental findings on unenhanced CT portion of PET/CT studies: frequency in 250 patients. J Nucl Med 2006;46:1352–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskandary H, Sabba M, Khajehpour F, Eskandari M. Incidental findings in brain computed tomography scans of 3000 head trauma patients. Surg Neurol 2006;63:550–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Mortele KJ, Silverman SG. Incidental extraurinary findings at MDCT urography in patients with hematuria: prevalence and impact on imaging costs. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185:1051–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel O, Yefremov N, Bar-Shalom R, Kagana O, Frenkel A, Keidar Z, et al. PET/CT detection of unexpected gastrointestinal foci of 18F-FDG uptake: incidence, localization patterns, and clinical significance. J Nucl Med 2005;46:758–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishimori T, Patel PV, Wahl RL. Detection of unexpected additional primary lesions with PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2005;46:752–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majumdar SR, Kim N, Colman I, Chahal AM, Raymond G, Jen H, et al. Incidental vertebral fractures discovered with chest radiography in emergency department. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:905–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ares Valdés Y, Fragás Valdés R. Incidental renal cell carcinoma. Arch Esp Urol 2005;58:417–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yee J, Kumar NN, Godara S, Casamina JA, Hom R, Galdino G, et al. Extracolonic abnormalities discovered incidentally at CT colonography in a male population. Radiology 2005;236:519–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell J, Kalra MK, Rizzo S, Maher MM, Shepard JA. Scanning beyond anatomic limits of the thorax in chest CT: findings, radiation dose, and automatic tube current modulation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;185:1525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng CS, Doyle TC, Courtney HM, Campbell GA, Freeman AH, Dixon AK. Extracolonic findings in patients undergoing abdomino-pelvic CT for suspected colorectal carcinoma in the frail and disabled patient. Clin Radiol 2004;59:421–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agress H, Cooper BZ. Detection of clinically unexpected malignant and premalignant tumors with whole-body FDG PET: histopathologic comparison. Radiology 2004;230:417–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang HW, No JH, Chung JH, Min YK, Lee MS, Lee MK, et al. Prevalence, clinical and ultrasonographic characteristics of thyroid incidentalomas. Thyroid 2004;14:29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schragin JG, Weissfeld JL, Edmundowicz D, Strollo DC, Fuhrman CR. Non-cardiac findings on coronary electron beam computed tomography scanning. J Thorac Imaging 2004;19:82–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellström M, Svensson MH, Lasson A. Extracolonic and incidental findings on CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy). AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;182:631–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginnerup Pedersen B, Rosenkilde M, Christiansen TE, Laurberg S. Extracolonic findings at computed tomography colonography. Gut 2003;52:1744–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai Q, Baumgarten DA, Affronti JP, Waring JP. Incidental findings of thickening luminal gastrointestinal organs on computed tomography: an absolute indication for endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1734–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzgerald TL, Smith AJ, Ryan M, Atri M, Wright FC, Law CH, et al. Surgical treatment of incidentally identified pancreatic masses. Can J Surg 2003;46:413–18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasegawa I, Boiselle PM, Raptopoulos V, Hatabu H. Tracheomalacia incidentally detected on CT pulmonary angiography of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1505–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmad NA, Ather MH, Rees J. Incidental diagnosis of diseases on un-enhanced helical computed tomography performed for ureteric colic. BMC Urol 2003;3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown J, Smith RC, Lee CH. Incidental enhancing lesions found on MR imaging of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1249–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Völk M, Strotzer M, Lenhart M, Techert J, Seitz J, Feuerbach S. Frequency of benign hepatic lesions incidentally detected with contrast-enhanced thin-section portal venous phase spiral CT. Acta Radiol 2001;42:172–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Messersmith WA, Brown D, Barry MJ. Incidental findings on ED abdominal CT scans. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:479–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weder W, Schmid RA, Bruchhaus H. Detection of extrathoracic metastases by positron emission tomography in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:886–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iko BO. Serendipity in cholangiography. Scand J Gastroenterol 1986;124:213–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferrucci JT. Clinical problem-solving: trapped by an incidental finding. N Engl J Med 2002;326:1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gutknecht DR. Meador revisited: nondisease in the nineties. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:873–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Royal HD, Siegel BA, Murphy WA., Jr An incidental finding: a radiologist's perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;160:237–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aron DC. The adrenal incidentaloma: disease of modern technology and public health problem. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2001;2:335–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacobs PC, Mali WP, Grobbee DE, van derGraaf Y. Prevalence of incidental findings in computed tomographic screening of the chest: a systematic review. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008;32:214–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]