Abstract

Objectives

This is a retrospective institutional review of clinical data and radiological findings of cerebral malaria patients presenting to a tertiary centre in India, which is an known to be endemic for malarial disease.

Methods

The present series describes MRI in four cases all of which revealed bithalamic infarctions with or without haemorrhages in patients with cerebral malaria, and this review examines a subset of patients with this condition. In addition, acute haemorrhagic infarctions were also seen the in brain stem, cerebellum, cerebral white matter and insular cortex in two of the four patients.

Results

In this series, the patient with cerebellum and brain stem involvement died. The remaining three survived with antimalarial and supportive treatment. No neurological symptoms were noted on clinical follow-up. MRI follow-up was obtained in only one of the three patients (3 months post-treatment) and showed resolution of thalamic infarctions.

Conclusion

These imaging features may help in the early diagnosis of cerebral malaria so that early treatment can begin and improve the clinical outcome.

Cerebral malaria is a life-threatening complication seen in 2% of malaria cases, particularly in Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum) infection. There is an estimated mortality rate of between 15% and 25% even with appropriate treatment and intensive care. However, patients who survive often recover fully with no long-term consquences. Early diagnosis and treatment is therefore crucial to obtain the best outcome [1-4]. With the availability of MR scanners in developing countries, where malaria is still an endemic health issue, a few case reports and series have already been published on the role of MR imaging in cerebral malaria. There have been occasional reports on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and gradient-echo imaging (GRE) with variable results.

Case series

The four cases included in this pictorial review comprised 3 males and 1 female aged between 25 and 55 years (mean, 40 years). A summary of the demographic data, clinical presentation, treatment and outcome of all the participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of demographic data, clinical presentation, staging, treatment and outcome of the participants.

| Participant | Age (years) | Gender | Presenting symptoms | Site of involvement | Treatment and clinical outcome |

| 1 | 48 | Male | Comatose on admission with GCS 4/15. History of fever, chills and rigors for 1 week accompanied by on/off generalised tonic-clonic seizures for 5 days. He also had frequent episodes of loss of consciousness. His peripheral smear for malarial parasite was positive. | Bilateral thalami, brain stem and cerebellar hemispheres (Figure 1) | Intravenous quinine dihydrochloride, intravenous fluids, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory drugs, however succumbed to death owing to advanced disease at the time of presentation |

| 2 | 32 | Female | Fever with chills and rigors for the past 10 days. Her liver function and renal function tests were deranged and the peripheral smear was positive for malarial parasites. She had a brief episode of loss of consciousness and two episodes of focal seizures, and responded to anticonvulsants. She had mild weakness in the bilateral extremity with power 4/5, her sensory examination was unremarkable. | Right corona radiata, posterior limb of bilateral internal capsule/thalami and left temporal lobe/hippocampus extending into the left insular cortex (Figure 2) | Gradually improvement with antimalarial and supportive treatment and was normal clinically at the time of discharge |

| 3 | 25 | Male | Fever, sudden blurring of vision followed by dizziness for 5–6 days. Neurological examination was unremarkable. Apart from positive peripheral smear for malaria, the remainder of biochemical and blood examinations were normal. | Bilateral thalami (Figure 3) | The patient gradually improved with antimalarial treatment and was normal clinically and radiologically at his last follow-up |

| 4 | 55 | Male | Sudden onset slurring of speech, diplopia and droop of left eyelid. He also had ataxia with tendency to fall. There was an episode of fever with chills 4 days back. He complained of loss of power in the right upper limb for 4 days. CNS examination revealed that he was conscious and orientated. Power in the right upper limb was 4/5. His sensory and motor systems were normal. The other systemic examinations were normal. Peripheral smear for malarial parasite was positive and the other biochemical and haematological investigations were normal. | Bilateral thalami and periaqueductal grey matter (Figure 4) | Antimalarial, antipyretics, and anti-inflammatory drugs. He improved clinically and was discharged. The patient did not have subsequent clinical or imaging follow-up |

CNS, central nervous system; GCS, Glasgow coma scale.

Discussion

Cerebral damage in malaria is due to vascular sequestration of parasitised erythrocytes and the potential cerebral toxicity by cytokines [3,5]. Red blood cells parasitised by P. falciparum adhere to capillary endothelium at a certain phase of the intraerythrocytic phase of the life-cycle of the parasite. It is thought that the parasites derive some nutrition from the endothelium. This phenomenon occurs mostly in the brain vessels, particularly in cortical and perforating arteries, resulting in perivascular ring-like haemorrhages and white matter necrosis [6,7]. Released cytokines could lead to vascular engorgement and vasodilatation leading to cerebral oedema and ischaemia [4,8]. If effective treatment for cerebral malaria is not introduced at this stage, these changes may become severe enough to lead to irreversible necrotic and haemorrhagic lesions of the perivascular myelin similar to lesions caused by fat emboli [4,6].

The neurological manifestations are non-specific because of the diffuse involvement of the brain. Transient extrapyramidal and neuropsychiatric manifestations, as well as isolated cerebellar ataxia, may occur. Patients can become drowsy and disorientated, altered consciousness is the most common neurological manifestation followed by seizures. As the disease process advances, the level of consciousness deteriorates and the patient becomes comatose.

Various reports of MRI in cerebral malaria have revealed focal or diffuse signal changes in centrum semiovale [3,9,10], corpus-callosum [3,11], thalamus and insular cortex [11,12]. Central pontine myelinolysis [13], myelinolysis in the upper medulla [14], cerebellar syndrome with demyelination, and microinfarcts of the cerebellar hemispheres [13] have also been reported. In these, hyperintensities on T2 weighted or fluid-attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) images were considered to be due to oedema, ischaemia, toxic injury or gliosis [3,9,12,14,15]. Looareesuwan et al [15] reported increased brain volume and brain swelling in patients with cerebral malaria. This difference was attributed to an increase in the volume of intracerebral blood caused by sequestration of parasitised erythrocytes and compensatory vasodilatation, rather than by oedema. A case report by Millan et al [9] and a case series by Cordoliani et al [3] both demonstrate haemorrhages and infarction in single cases. The interpretation was based on T1 and T2 weighted and FLAIR images. Haemorrhages based on gradient-echo imaging in single cases were described by Gupta et al [12] and Nickerson et al [16]. The lesions were mainly in the frontoparietal lobe, corpus callosum and internal capsule. However, no restricted diffusion was demonstrated. A case report by Sakai et al [17] described periventricular and subcortical white matter restricted diffusion on the DWI, but did not reveal haemorrhagic components. Yadav et al [11] described MRI including DWI and GRE in three patients with altered sensorium where all patients had focal white matter, corpus-callosam lesions and symmetrical thalamic abnormality. None showed restricted diffusion or haemorrhage. Infarcts in the basal ganglia, thalamus, pons and cerebellum on CT have previously been described by Patankar et al [4], who attributed the changes to cytotoxic oedema. Areas of petechial haemorrhage seen on autopsy are considered the hallmark of cerebral malaria at pathological examination and were not seen on their CT scans.

DWI and GRE imaging are known to be extremely sensitive for the detection of cytotoxic oedema and blood degradation products, respectively and have demonstrated acute infarctions in bilateral thalami in all our cases and thalamic haemorrhages in three of our cases. In addition, acute haemorrhagic infarctions are also seen in the brain stem, cerebellum, cerebrum and hippocampus. To conclude, although reported MRI features of cerebral malaria are variable, the diagnosis of cerebral malaria should be strongly considered when acute haemorrhagic infarctions, particularly in the thalami, are encountered in patients with constitutional symptoms with or without history of travel to an endemic area.

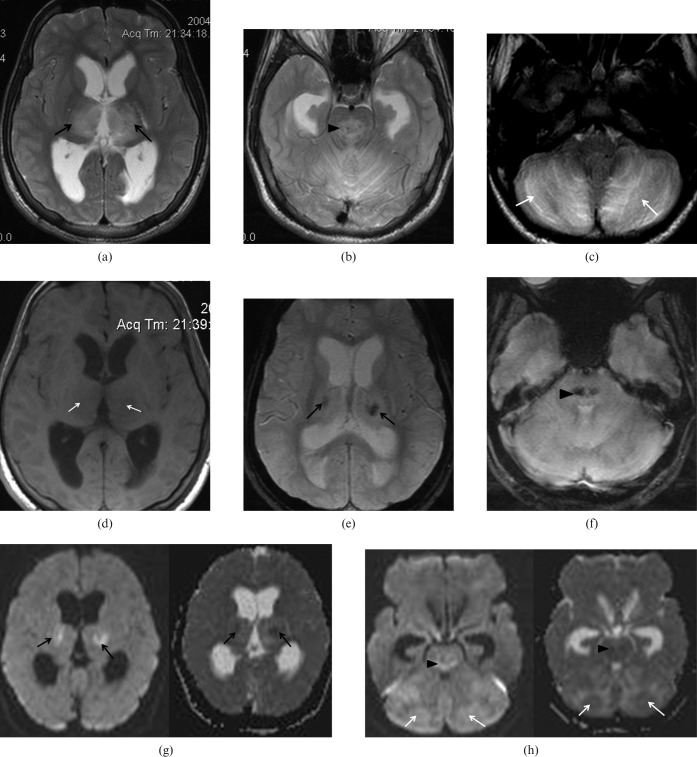

Figure 1.

48-year-old male found comatose on admission with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 4/15. Axial T2 weighted images showing multiple foci of hyperintensities in (a) bilateral thalami (black arrows); (b) brain stem (arrowhead); and (c) cerebellar hemispheres (white arrows). (d) Axial T1 weighted image showing corresponding hypointensities in the bilateral thalami (white arrows). Axial gradient-echo images show blooming artefacts in (e) bilateral thalami (black arrows) and (f) brain stem (arrowhead) compatible with petechial haemorrhages. Axial diffusion weighted images showing restricted diffusion in (g) bilateral thalami (black arrows), (h) brain stem (arrowheads) and cerebellar hemispheres (white arrows).

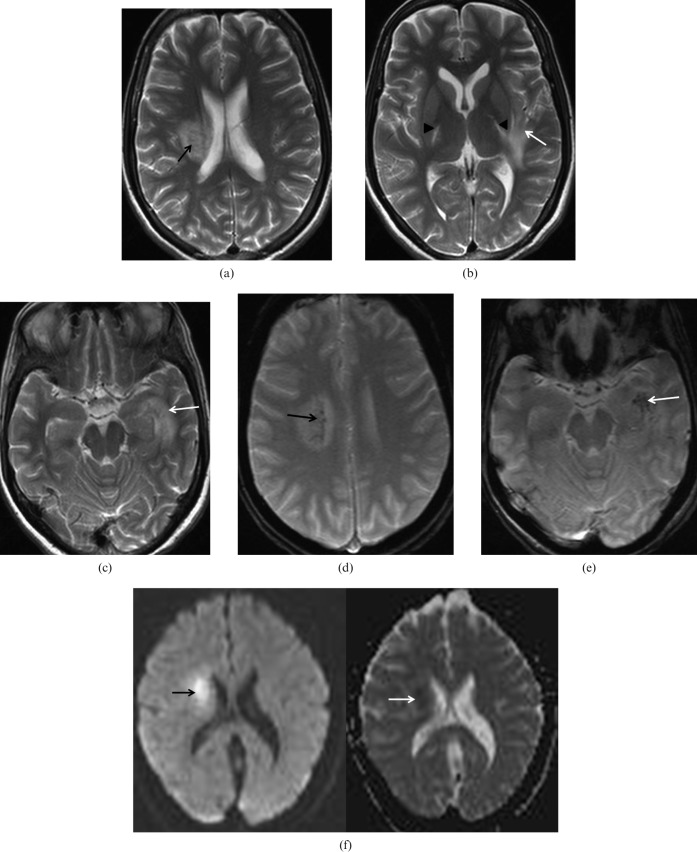

Figure 2.

A 32-year-old female presented with a history of fever, chills and rigors for the past 10 days. Axial T2 weighted images show multiple foci of hyperintensities in the (a) right corona radiata (black arrow), (b) posterior limb of bilateral internal capsule/thalami (arrowheads) and (c) left temporal lobe/hippocampus extending into the left insular cortex (white arrows). Axial gradient-echo images showing old haemorrhages in (d) right corona radiata (black arrow) and (e) left temporal lobe/hippocampus (white arrow). Axial diffusion-weighted images showing restricted diffusion in right corona radiata (arrows).

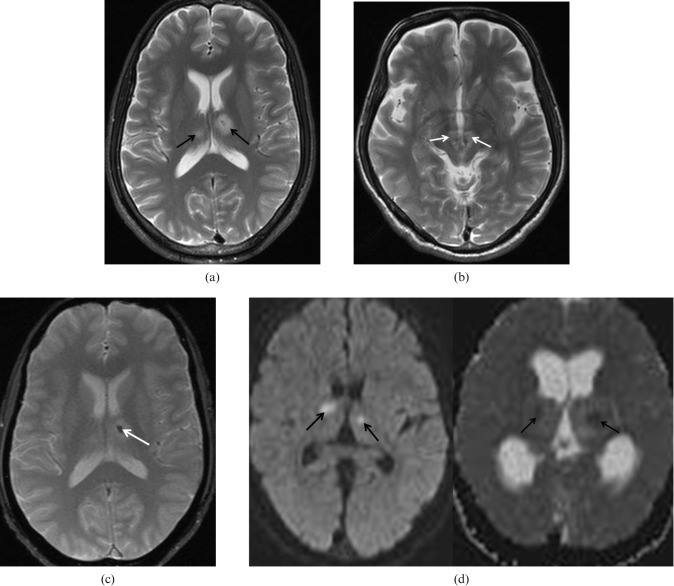

Figure 3.

A 25-year-old male presented with history of fever and sudden blurring of vision followed by dizziness for 5–6 days. Axial diffusion-weighted images showing restricted diffusion in bilateral thalami (arrows).

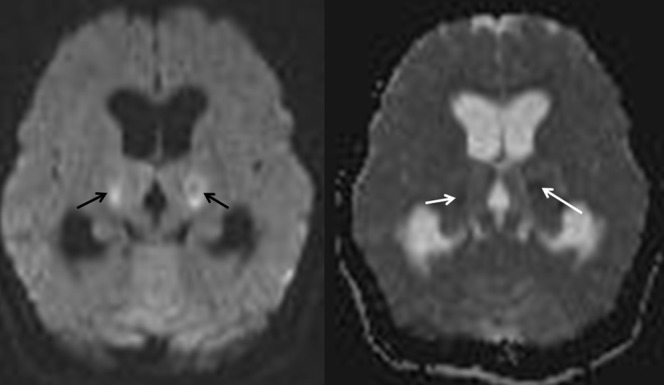

Figure 4.

A 55-year-old male presented with sudden onset slurring of speech, diplopia and droop of left eyelid. (a) Axial T2 weighted images showing multiple foci of hyperintensities in bilateral thalami (black arrows) and (b) periaqueductal grey matter (white arrows). (c) Axial gradient-echo image showing petechial haemorrhages in the left thalamus (white arrow). (d) Axial diffusion weighted images showing restricted diffusion in the thalami (black arrows) and periaqueductal grey matter extending into the brain stem (white arrow).

References

- 1.Stoppacher R, Adams SP. Malaria deaths in the United States: case report and review of deaths, 1979–1998. J Forensic Sci 2003;48:404–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller O, Traore C, Becher H, Kouyate B. Malaria morbidity, treatment-seeking behaviour, and mortality in a cohort of young children in rural Burkina Faso. Trop Med Int Health 2003;8:290–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordoliani YS, Sarrazin JL, Felten D, Caumes E, Leveque C, Fisch A. MR of cerebral malaria. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:871–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patankar TF, Karnad DR, Shetty PG, Desai AP, Prasad SR. Adult cerebral malaria: prognostic importance of imaging findings and correlation with postmortem findings. Radiology 2002;224:811–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner GD, Morrison H, Jones M, Davis TM, Looareesuwan S, Buley ID, et al. An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria. Evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am J Pathol 1994;145:1057–69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janota I, Doshi B. Cerebral malaria in the United Kingdom. J Clin Pathol 1979;32:769–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toro G, Roman G. Cerebral malaria. A disseminated vasculomyelinopathy. Arch Neuro 1978;35:271–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Looareesuwan S, Warrell DA, White NJ, Sutharasamai P, Chanthavanich P, Sundaravej K, et al. Do patients with cerebral malaria have cerebral oedema? A computed tomography study. Lancet 1983;1:434–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millan JM, San Millan JM, Munoz M, Navas E, Lopez-Velez R. CNS complications in acute malaria: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993;14:493–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamanagatti S, Kandpal H. MR imaging of cerebral malaria in a child. Eur J Radiol 2006;60:46–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yadav P, Sharma R, Kumar S, Kumar U. Magnetic resonance features of cerebral malaria. Acta Radiol 2008;49:566–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Patel K. Case series: MRI features in cerebral malaria. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2008;18:224–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kampfl AW, Birbamer GG, Pfausler BE, Haring HP, Schmutzhard E. Isolated pontine lesion in algid cerebral malaria: clinical features, management, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993;48:818–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saissy JM, Pats B, Renard JL, Dubayle P, Herve R. Isolated bulb lesion following mild Plasmodium falciparum malaria diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Intensive Care Med 1996;22:610–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Looareesuwan S, Wilairatana P, Krishna S, Kendall B, Vannaphan S, Viravan C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in patients with cerebral malaria. Clin Infect Dis 1995;21:300–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickerson JP, Tong KA, Raghavan R. Imaging cerebral malaria with a susceptibility-weighted MR sequence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:e85–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai O, Barest GD. Diffusion-weighted imaging of cerebral malaria. J Neuroimaging 2005;15:278–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]