Abstract

Spinal paragonimiasis is a rare form of ectopic infestation caused by Paragonimus westermani. We report a case of pathologically proven intradural paragonimiasis associated with concurrent intracranial involvement. MRI revealed multiple well-defined intradural masses that were markedly hypointense on T2 weighted images and hypointense with a peripheral hyperintense rim on T1 weighted images. Contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images showed slight peripheral rim enhancement.

Paragonimiasis caused by Paragonimus westermani and related species occurs in Asia, Africa and South America, but most commonly in Korea, Japan and China [1,2]. Human infestation by P.westermani occurs from ingestion of raw or incompletely cooked freshwater crabs or crayfish infected with the encysted larvae of the fluke. The ingested juvenile worms (metacercariae) of P.westermani penetrate the intestinal wall, the peritoneum and the diaphragm, finally invading the pleural cavity and the lung where they become mature adult worms [3,4].

The complicated biology of P.westermani is the reason why paragonimiasis can occur throughout the human body [1]. Extrapulmonary paragonimiasis has been reported in several sites, including the brain, spinal cord, abdomen, appendix, inguinal region, subcutaneous tissue, eye, thigh and genitals [5].

The central nervous system (CNS) is known to be the most common site of extrapulmonary paragonimiasis. The rate of cerebral paragonimiasis is approximately 0.8% of all active paragonimiasis [1]. However, spinal paragonimiasis is very rare compared with the incidence of cerebral paragonimiasis (less than 10% of cerebral paragonimiasis) [6].

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous report describing the imaging features of spinal paragonimiasis in the English language literature. In this case report, we described imaging features of a case of pathologically proven spinal paragonimiasis with emphasis on the MRI findings.

Case report

A 44-year-old female presented with severe neurogenic claudication owing to spondylolisthesis at the level of L4–L5. Neurological examination revealed right side homonymous hemianopsia and monoparesis in the right arm. Laboratory data including peripheral blood examination and blood chemistry revealed normal ranges and stool examination for parasitic eggs was negative. The level of Paragonimus specific antibody (IgG) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was borderline negative (0.224; normal range, 0–0.28) on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

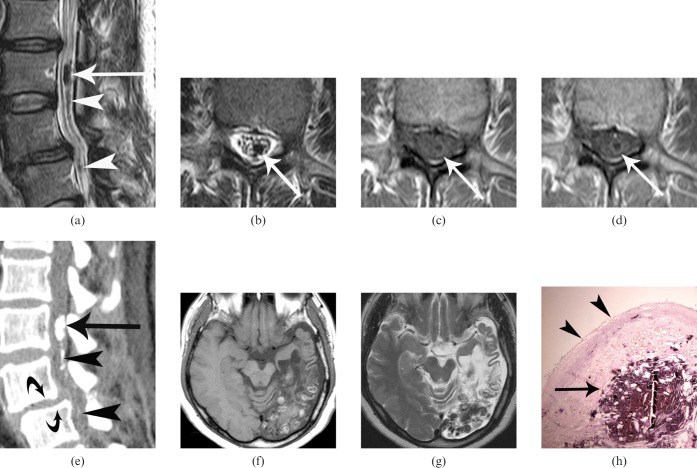

MRI of the lumber spine revealed multiple well-defined intradural masses. They appeared marked hypointense on T2 weighted images (Figures 1a,b). T1 weighted images showed masses to be hypointense relative to CSF with a peripheral hyperintense rim (Figure 1c). Post-contrast T1 weighted images showed slight peripheral rim enhancement (Figure 1d). CT scan showed multiple calcified nodules in the lumbar intradural space (Figure 1e). MRI of the brain revealed multiple well-defined nodular or cystic masses in the left occipital and parietal lobes that had mixed signal intensity on both T1 and T2 weighted images, with no contrast enhancement (Figures 1f,g).

Figure 1.

A 44-year-old female with spinal paragonimiasis associated with cerebral involvement. (a) Sagittal and (b) axial T2 weighted MRI show an oval-shaped, markedly hypointense mass (arrows) in the intradural space at the level of L3 vertebral body. Note other multiple small markedly hypointense nodules (arrowheads in (a)). (c) Axial T1 weighted MRI shows the same mass (arrow) as (b) that appears as an isointense area with a peripheral hyperintense rim. (d) Contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images show slight peripheral enhancement (arrow). (e) Sagittal reconstruction of CT scan demonstrates a calcified mass (arrow) at the level of L3 vertebra and another multiple small calcifications (arrowheads) in the intradural space. Note spondylolisthesis at the L4–L5 levels (curved arrows). (f) Axial T1 weighted MRI shows a cluster of multiple small nodules with heterogeneous high-signal intensity in the left occipital lobe associated with localised cortical atrophy, subcortical cerebromalacia and secondary ventricular dilatation. No contrast enhancement was seen after contrast administration (not shown). (g) Axial T2 weighted MRI obtained at the same level as (f), shows that nodules appear as heterogeneously hypointense areas. (h) Photomicrograph of the surgical specimens shows the cystic granulation tissue containing degenerative and calcified materials (arrow) and the outer fibrous wall (arrowheads) (haematoxylin-eosin, ×40). Many Paragonimus westermani eggs were scattered in the cyst and the inner surface of the fibrotic wall (not shown).

A presumptive diagnosis of spinal and cerebral paragonimiasis was made based on the image obtained from CT and MRI examinations. The patient underwent lumbar fusion for coincident spondylolisthesis, hemilaminectomy of the L3 and complete excision of encapsulated intradural cystic masses containing creamy fluid. There were severe adhesions between masses and nerve roots, granulation tissue and diffuse thickening of arachnoid membrane, indicating chronic arachnoiditis. However, the dura was shiny white without any evidence of inflammation. Histopathology of the resected specimen confirmed the diagnosis of paragonimiasis (Figure 1h).

Discussion

CNS is known to be the most common site of extrapulmonary paragonimiasis [1]. Although cerebral paragonimiasis is not an uncommon disease in East Asian countries, spinal involvement is rare [6]. In the spine, epidural involvement is more common than intradural. In a previous study, Oh [6] reported that only 3 cases involved the intradural space among 24 cases of spinal paragonimiasis. In his report, all three intradural type spinal paragonimiasis had concurrent cerebral paragonimiasis and previous history of craniotomy. Although the route of infection to the spinal canal is not yet known, the theory of direct migration of larvae from the lung has received the widest support. Another hypothesis is the possibility of direct dissemination of larvae intradurally from the brain to spinal canal via CSF with the help of gravity or craniotomy [6]. The fact that no granulation tissue in the epidural space or inflammation in the dura was found in our case supports the hypothesis of the dissemination of larvae from the brain. Furthermore, the patient had no history of craniotomy owing to the brain lesion, suggesting that the craniotomy is not essential factor of migration.

As described in previous literature [7-13], there are a variety of imaging findings for paragonimiasis depending on the stage of the infection. The initial intracranial lesions of cerebral paragonimiasis include exudative aseptic inflammation, haemorrhage and infarction [7]. In time, granulomatous lesions are formed around the adult P.westermani. In this stage, the most common and characteristic imaging finding is conglomerated, multiple ring-shaped enhancement resembling a “grape cluster” with surrounding oedema [8-10]. Each ring is usually smooth and round or oval, ranging from a few millimeters to 3 cm in diameter. The central portion of the granulomas shows a density/intensity similar to or slightly higher than that of CSF on both CT and MRI of all pulse sequences. The wall is usually isointense relative to brain parenchyma on T1 weighted images and isointense or hypointense on T2 weighted images.

In the chronic stage, liquefaction necrosis and fibrinous gliosis occur around the granulomas. The granulomas shrink and invariably become calcified. The calcifications may appear to be punctate or amorphous, round or oval, nodular or cystic, solitary or congregated on plain skull radiograph [11] and CT [12]. On MRI, the calcifications appear as signal void or hypointense nodules and not infrequently as “egg-shell appearance” with central content of low- or high-intensity [13].

We present a case of spinal paragonimiasis associated with concurrent cerebral involvement. Our case had multiple calcified nodules in the intradural space of the lumber spine, which appeared as a hypointense area on T1 weighted image and marked hypointense area on T2 weighted image. The wall is seen as a high-signal intensity rim on T1 weighted image, which shows slight enhancement following intravenous contrast administration. The findings are similar to the features of cerebral paragonimiasis in the chronic stage described in previous studies [13].

In contrast to most previously reported cases, the diagnosis of paragonimiasis was established on the basis of the histopathological examination of the resected specimen and radiological-pathological correlation was possible in our case. The CT and MRI features of multiple calcified nodules are reflections of cystic granulomas containing necrotic and calcified debris with scattered P.westermani ova histologically. The peripheral high–signal intensity on T1 weighted image with ring enhancement was the wall of cystic granuloma composed of an inner granulation tissue and outer fibrous layer (Figure 1h).

Differential diagnoses of the intradural paragonimiasis include granulomas of other aetiology, most commonly of tuberculosis, cysticercosis or hydatid cysts. The clinical signs and symptoms of CNS paragonimiasis are non-specific. Spinal symptoms may include hemiparesis, hypoaesthesia, paraplegia and cauda equina syndrome [6]. The antibody test by ELISA for Pragonimus specific antibody (IgG) in CSF, commonly used to confirm a presumptive diagnosis of paragonimiasis, is not always conclusive in the diagnosis of a chronic CNS paragonimiasis [9]. Thus, knowledge of imaging findings is helpful in differentiating various intradural lesions found in the spine.

As shown in the present case, intradural paragonimiasis has its own characteristic imaging findings, which are similar to the findings of cerebral paragonimiasis.

References

- 1.Oh SJ. Cerebral and spinal paragonimiasis. A histopathological study. J Neurol Sci 1969;9:205–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi 1990;28:79–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DC. Paragonimus westermani: life cycle, intermediate hosts, transmission to man and geographical distribution in Korea. Arzneimittelforschung 1984;34:1180–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokogawa M. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis. Adv Parasitol 1965;3:99–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung S. Extrapulmonary paragonlmiasis, review of literature with a case report of cerebral paragonimiasis. J Formosa med Ass 1958;51:500–7 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh SJ. Spinal paragonimiasis. J Neurol Sci 1968;6:125–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh SJ. Cerebral paragonimiasis. J Neurol Sci 1969;8:27–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang KH, Han MH. MRI of CNS parasitic diseases. J Magn Reson Imaging 1998;8:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang KH, Cha SH, Han MH, Kim HD, Cho SY, Kong Y, et al. An imaging diagnosis of cerebral paragonimiasis: CT and MR findings and correlation with ELISA antibody test. J Korean Rad SOC 1993;29:345–54 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha SH, Chang KH, Cho SY, Han MH, Kong Y, Suh DC, et al. Cerebral paragonimiasis in early active stage: CT and MR features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;162:141–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh SJ. Roentgen findings in cerebral paragonimiasis. Radiology 1968;90:291–9 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Udaka F, Okuda B, Okada M, Tsuii T, Kameyama M. CT findings of cerebral paragonimiasis in the chronic state. Neuroradiology 1988;30:31–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomura M, Nitta H, Nakada M, Yamashima T, Yamashita J. MRI findings of cerebral paragonimiasis in chronic stage. Clin Radiol 1999;54:622–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]