Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has a more variable clinical course than has been traditionally recognised. Many patients will remain stable over time while others experience relatively rapid deterioration. The prognosis and clinical course of patients with other fibrosing lung diseases is also variable. A number of conditions may complicate the clinical course of the idiopathic fibrosing lung diseases, which results in morbidity and mortality, but also represents potentially treatable causes of worsening symptoms. Infection and malignancy have a long-recognised association with IPF while other conditions, particularly pulmonary hypertension and acute exacerbation of IPF, are being increasingly recognised in this patient population. Many of these patients have serial high-resolution CT (HRCT) examinations that may demonstrate one or more of these supervening conditions. In this article we review the more common conditions that may complicate the course of idiopathic fibrosing lung disease with an emphasis on the HRCT appearance, which the reporting radiologist should be aware of.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) are the two main idiopathic fibrosing lung diseases defined by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society consensus statement [1]. IPF, the clinical syndrome associated with the histological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), is the commonest of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and has a poor prognosis, with median survival times of between 3 and 5 years [2-4]. Survival in IPF/UIP is worse than in NSIP [2,5], but the clinical course of IPF is variable and many patients remain stable over time while others experience relatively rapid deterioration [6]. Similarly, the clinical course and prognosis of NSIP is not uniform with worse survival in the fibrosing subtype compared with the less common cellular subtype [2,7]. In addition to this unpredictability, a wide range of conditions can complicate the course of pulmonary fibrosis, and many of these are readily treatable. Infection and malignancy have long been recognised as complications of pulmonary fibrosis, but there is increasing awareness of other important supervening conditions, particularly acute exacerbation and pulmonary hypertension (PH), which have implications both for prognosis and treatment [8-10].

HRCT has a central role in the diagnosis of diffuse parenchymal lung disease and has improved the ability to make a definitive diagnosis without the need for lung biopsy in some disorders, particularly IPF [8]. HRCT has a high positive predictive value for the pathological diagnosis of UIP when the HRCT changes are classical (honeycombing in a basal and subpleural distribution) [11]. These classical findings as well as a greater extent of fibrosis predict a worse mortality, and thus HRCT has a prognostic as well as diagnostic role in IPF [12,13]. Approximately half of the cases of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia do not have the typical HRCT appearances of UIP [14], and in these circumstances lung biopsy is recommended because the distinction of histological UIP from NSIP has important prognostic implications [2,5]. In addition to its diagnostic and prognostic role, HRCT may demonstrate one of the several conditions associated with fibrosing lung disease. In this review the most common conditions that can complicate idiopathic fibrotic lung disease will be discussed, with an emphasis on HRCT appearances.

Pulmonary infection in IPF

Patients with diffuse fibrotic lung disease are susceptible to a range of pulmonary infections, particularly those caused by Mycobacterium species, Aspergillus species and a number of opportunistic infections, importantly Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) [15-19]. Even modest immunosuppressive regimens used in the treatment of IPF may increase susceptibility to PCP infection. HRCT may be valuable in evaluating infection in patients with fibrotic lung disease, particularly as the pre-existing pulmonary abnormality may mask the typical radiographical appearances of these infections.

Opportunistic infection

A high prevalence of P. jirovecii colonisation has been reported in patients with interstitial lung disease [19], but the risk of developing clinical infection is probably not particularly increased compared with the general population. The exception may be patients receiving corticosteroid therapy as even moderate corticosteroid doses of relatively short duration (8 weeks or less) have been reported to increase susceptibility to P. jirovecii infection [20]. The characteristic HRCT appearances of PCP in patients with otherwise normal lungs are those of bilateral, symmetric and extensive ground-glass opacity, consolidation and septal thickening [21]. The distribution is typically perihilar and upper zone with sparing of subpleural lung. However, in the context of IPF, the appearance of PCP may be indistinguishable from acute exacerbation of IPF (Figure 1). It is also noteworthy that the HRCT appearance may be unchanged from the patient's baseline in the presence of clinically significant PCP infection.

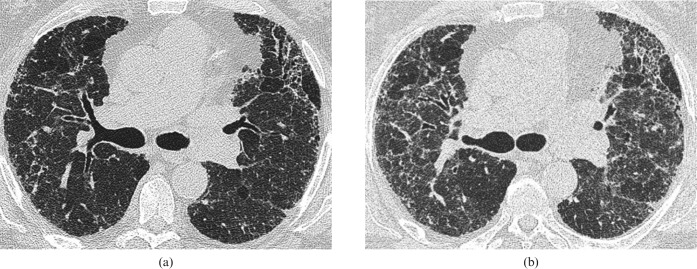

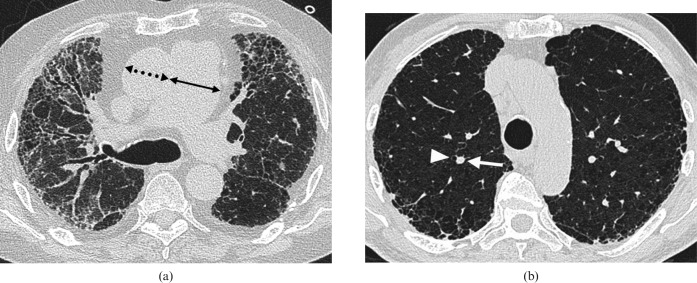

Figure 1.

Images from a 60-year-old man with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia complicated by Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP). The patient was on immunosuppressive treatment (prednisolone and azathioprine). (a) Baseline high-resolution CT (HRCT) through the mid-zones. (b) 2 months later following a week-long history of breathlessness, HRCT shows subtle, patchy ground-glass opacification superimposed on the fibrotic lung disease. A sputum sample stained positive for PCP.

Anecdotally, patients with IPF do not seem more prone to community acquired bacterial pneumonias than the general population.

Mycobacterial infection

An increased prevalence of conventional reactivation pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) has been reported in patients with IPF [15,16]. Importantly, the radiological manifestations of pulmonary TB in patients with IPF may be atypical. In one study of patients with IPF and confirmed pulmonary TB infection, HRCT examination demonstrated peripheral mass-like lesions in 67% of patients [15]. Segmental or lobar consolidation, with and without necrotising cavitation, occurred in 33% with typical patterns of reactivation TB, including patchy multifocal consolidation and centrilobular nodules, infrequently observed. An awareness of these atypical HRCT appearances is important, both because the peripheral, solid mass-like lesions may resemble IPF-associated lung cancer (Figure 2) and because TB is a readily treatable cause of clinical deterioration in these patients.

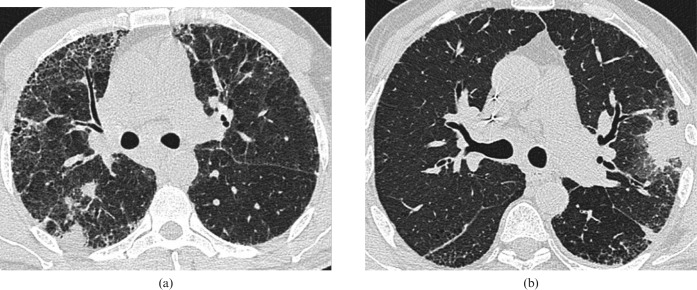

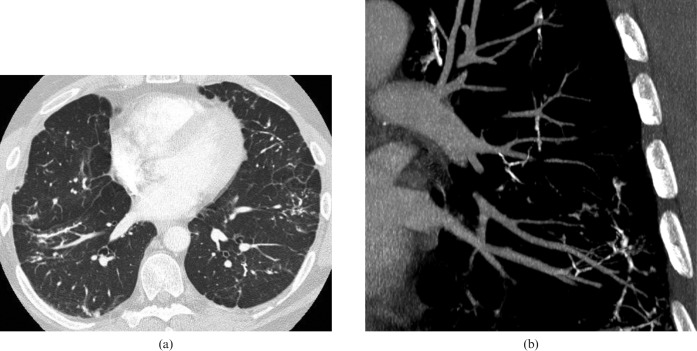

Figure 2.

(a,b) Two cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in fibrotic lung disease. In both instances a biopsy of the peripheral focal areas of consolidation were taken as part of an investigation for suspected lung cancer. No malignant cells were identified in either biopsy sample; however, tissue examination showed typical caseating granulomatous changes associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. Anti-tuberculosis therapy led to radiological resolution in both cases.

In contrast to patients with other chronic lung diseases, patients with IPF do not seem more susceptible to infection with non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) species than the general population. In a series of 21 patients with Mycobacterium fortuitum infection, 15% had underlying IPF [22]. However, the specific appearances of NTM infection in patients with IPF are not described in this study or, to our knowledge, elsewhere in the literature.

Aspergillus infection

The form that pulmonary disease takes when caused by the ubiquitous Aspergillus species depends on the host's immune response, the local lung architecture and the concentration of the inoculum [23]. Patients with IPF are at risk of developing aspergillomas (resulting from saprophytic colonisation of a pre-existing lung cavity) and chronic airway invasive aspergillosis (an indolent form of cavitatory Aspergillus infection, also termed chronic necrotising or semi-invasive aspergillosis). It is now recognised that there is overlap between these clinicopathological entities [24] and therefore the simpler term “aspergillosis” may be more appropriate when the distinction of simple mycetoma from chronic airway invasive aspergillosis is not obvious.

Although aspergilloma most frequently develops in a cavity resulting from advanced fibrotic sarcoidosis or from previous TB, the condition has been described in a range of other fibrocavitary disease, including IPF [17,24,25]. Surrounding fibrotic scarring and pre-existing lung disease impair detection of aspergillomas on chest radiograph and CT is more sensitive than chest radiography, detecting both early changes and smaller lesions [17,25]. In the early stages, CT may depict the initial fungal fronds arising from the cavity wall, which subsequently detach and coalesce to form the classic intracavitary mass with an adjacent air crescent [25] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mycetoma in the left lower lobe within the fibrotic lung (histopathological type unknown) in a 45-year-old woman.

Saraceno et al [18] reviewed the literature on chronic airway invasive aspergillosis and found that 15 out of 59 patients had underlying interstitial lung disease. Focal consolidation, typically at the lung apices, with adjacent pleural thickening, progresses to cavitation because the fungus locally invades and destroys the lung parenchyma (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Chronic necrotising aspergillosis in a 60-year-old man with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Within the fibrobullous lung there is consolidation and an intracavitary body (air crescent sign). Following an extended course of antibacterial therapy without improvement, a positive culture for Aspergillus fumigatus was obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage of the right upper lobe.

Malignancy

Epidemiology

A number of epidemiological studies have reported an increased risk of lung cancer in patients with IPF [26-29]. A recent large study in the UK, using a longitudinal primary care database, found an approximate five-fold increase in incidence of lung cancer in patients with IPF compared with the general population control cohort [27].

Age, gender and smoking status are positively associated with the risk of developing lung cancer in IPF [26,30,31]. Smoking is a risk factor for both IPF (controversially) and lung cancer (definitely), and therefore may be a confounding factor in studies examining the association between the two conditions. However, the increased risk of lung cancer in patients appears to change little following adjustment for the effect of smoking status, suggesting that the increase in the prevalence of lung cancer in IPF is independent of smoking [27]. Although there are a small number of cases in the literature of primary lung cancer occurring in cases of NSIP [32], much less is known about lung cancer in the setting of fibrosing lung diseases other than IPF.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of lung cancer in pulmonary fibrosis remains unknown. Inflammatory mediators may cause repeated episodes of cellular damage and genetic injury to the respiratory epithelium with stepwise development of cellular atypia, metaplasia, dysplasia and eventually invasive carcinoma [33]. Most studies of cancer in IPF have found the majority of tumours occur in a peripheral basal location, i.e. reflecting the distribution of fibrosis, suggesting that the fibrotic process may have a role in the development of cancer.

There are conflicting reports about the distribution of histological types of lung cancer in patients with IPF and whether it differs from that observed in lung cancer patients without IPF [34]. A number of studies have found squamous cell carcinoma to be the commonest type [30,31,35-37] while others have reported adenocarcinoma as occurring most frequently [38,39]. Synchronous tumours have also been reported to occur more frequently in patients with IPF than in those without IPF [35,40].

Radiology of lung cancer in IPF

An early study of the CT appearances of lung cancer in IPF found that the majority of tumours were ill-defined lesions with some mimicking air-space consolidation [36]. Two subsequent studies found that most cancers were well-defined nodular lesions [37,41] (Figure 5). Sakai et al [37] compared CT (both conventional and HRCT) appearances with pathological findings of 57 lung cancers in 47 patients with diffuse pulmonary fibrosis. 82% of tumours were found within or abutted areas of peripheral honeycombing. Of the 29 tumours resected at either surgery or autopsy, those with a sharp margin on CT were discrete masses with intact but compressed adjacent honeycomb lung. In seven tumours (six squamous cell carcinomas and one small cell carcinoma) there was an indistinct interface between the mass and adjacent honeycombing on CT.

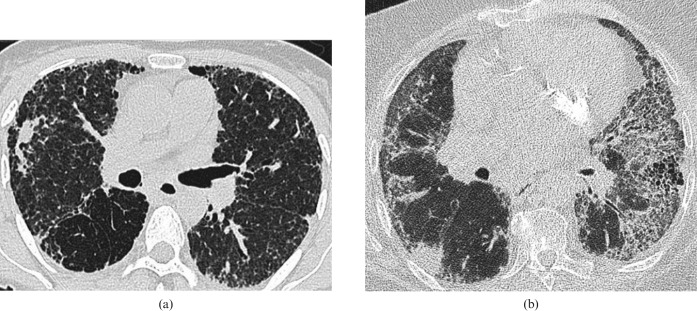

Figure 5.

Two examples of peripheral primary adenocarcinoma in fibrotic lung disease. (a) Biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma in the right upper lobe of a patient with fibrotic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (and some admixed paraseptal emphysema). (b) Peripheral adenocarcinoma in the right lower lobe of a 62-year-old man with usual interstitial pneumonia.

Kishi et al [41] also found that the large majority of tumours were well-defined nodular lesions located in the periphery of the lung, but 2 of 30 tumours were classified as having an indeterminate pattern on CT. Extensive pleural thickening resembling mesothelioma was found in a case of adenocarcinoma. In another case, diffuse ground-glass opacity within honeycomb lung was proven histologically to be mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, highlighting the difficulty in distinguishing this form of cancer from areas of confluent fibrosis. In contrast to the high rate of occurrence of tumours in areas of honeycombing found in these two studies [37,41], Park et al [31] reported a low concordance rate of lung cancer with fibrotic lesions in IPF with the majority of tumours (64%) found in non-fibrotic areas at chest CT.

Prognosis and treatment

Given the already poor prognosis of IPF, with median survival times as low as 2.9 years in the published literature [4], it is unclear what impact the diagnosis of lung cancer has on survival in the IPF population. In a recent study the median survival time after diagnosis of lung cancer in patients with IPF was 13.1 months [29]. With this poor prognosis in mind, a number of studies have examined the role of treatment, in particular surgical resection, for patients with lung cancer and IPF.

Unsurprisingly, patients with IPF who undergo resection for lung cancer have significantly higher rates of post-operative mortality and morbidity, as well as worse long-term outcomes, than patients without IPF who undergo pulmonary resection. Hospital mortality rates for IPF patients range from 7.1% to 18.2% with post-operative acute exacerbations of IPF the major cause of death [42-45]. Rates of post-operative exacerbations of IPF are related to the extent of resection, with significantly higher rates in patients undergoing pneumonectomy than lobectomy and no significant difference in post-operative mortality and morbidity in patients with pulmonary fibrosis undergoing limited resections (segmentectomy or wedge resection) compared with the general lung cancer population [42,43]. Some studies have suggested that pre-operative pulmonary function tests may predict increased risk of post-operative exacerbations [42,45], but other studies have not found a link between pre-operative pulmonary status and post-operative acute exacerbations [43].

The outcome following lung cancer resection is worse for patients with IPF than the general lung cancer population for a variety of reasons. Watanabe et al [43] reported a 5 year actuarial survival rate of 61% in patients with Stage I lung cancer and IPF compared with 83% in the general lung cancer population. A proportion of late deaths are due to IPF complications but some studies have also reported higher rates of second lung cancers in the IPF patient group than in the general lung cancer population.

Non-surgical treatment of lung cancer in IPF patients is complex, with a full discussion beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth noting that exacerbations of IPF have been reported following both radiotherapy and chemotherapy for lung cancer. In a case of subclinical IPF, detected on CT prior to treatment, acute exacerbation of IPF occurred following hypofractionated steroeotactic body radiotherapy for primary lung cancer [46]. This highlights the importance of the radiologist in reporting fibrotic lung disease in cases with concomitant lung cancer, as clinicians may not be aware of the presence of pulmonary fibrosis. Patients with pre-exisiting interstitial lung disease, mainly IPF, are also at increased risk of developing acute episodes of interstitial lung disease following treatment for lung cancer with both conventional chemotherapy and the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, gefitinib [47].

The important imaging characteristics of lung cancer in IPF are summarised in Table 1. While a peripheral mass lesion is the most common presentation of lung cancer in IPF, it is important to recognise the less typical pattern of diffuse amorphous opacification superimposed on a background of fibrosis.

Table 1. Lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

| Key imaging points |

| Most lung cancers in patients with IPF manifest as peripheral mass-like lesions occurring in or near areas of fibrosis |

| Synchronous tumours are more common compared with patients without IPF |

| Distinction of tumours from areas of confluent fibrosis may be very difficult and comparison with previous imaging is important |

Acute deterioration in IPF patients

The natural history of IPF can be characterised as a steady and predictable deterioration in symptoms and lung function over time, with median survival from diagnosis of between 3 and 5 years [2-4]. However, many patients will experience more acute deterioration in symptoms and pulmonary function owing to one of several causes. Much information about the clinical course of IPF has been gained from a study of 168 patients with mild-to-moderate IPF in the placebo arm of a clinical trial, followed for an average of 76 weeks [6]. Almost one-quarter of patients had one or more episodes of hospitalisation for respiratory disorders. Of 36 patients who died, 32 deaths were IPF-related and, of these, almost half were deemed acute, occurring within 4 weeks of decompensation.

Imaging has a role in establishing the cause of acute deterioration, although HRCT appearances are often non-specific with diffuse ground-glass opacity on a background of pre-existing fibrosis being common to many of the diseases discussed below. Table 2 lists the important causes of diffuse increase in parenchymal density on HRCT in IPF patients.

Table 2. Causes of a diffuse increase in attenuation of the lung parenchyma on high resolution CT in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

| Cause |

| Acute exacerbation of IPF |

| Pulmonary oedema |

| Drug-induced pneumonitis |

| Infection (especially Pneumocystis jirovecii and viruses) |

| Technical factors (spurious increased opacification) |

| Scan acquired at end expiration |

| Intravenous contrast administration e.g. for CT pulmonary angiogram |

Acute exacerbation of IPF

Acute exacerbation of IPF (also termed accelerated phase) is an acute, clinically significant deterioration of an unidentifiable cause in a patient with underlying IPF. Proposed diagnostic criteria comprise previous or concurrent diagnosis of IPF; unexplained worsening or development of dyspnoea within 30 days; HRCT demonstrating new parenchymal opacity on a background of reticular or honeycomb pattern consistent with UIP; exclusion of alternative causes, including infection, left heart failure or identifiable cause of acute lung injury [48].

Acute exacerbation is increasingly recognised as an important and relatively common complication of IPF. In a recent population-based study, 17 out of 47 patients with IPF experienced 1 or more episodes of acute exacerbation in the 9 year study period, with a rate of IPF-related exacerbation of 13% per person-year [49]. Kim et al [50] reported a 1 year frequency of acute exacerbation of 8.5% and a 2 year frequency of 9.6% in their retrospective study of 147 patients with biopsy-proven IPF. Acute exacerbations of other fibrotic lung diseases, including idiopathic NSIP and fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, have also been described, with some suggestion that outcome of acute exacerbation in NSIP may be better than in UIP [51-53].

Although the trigger for acute exacerbation is unknown, an association with surgical lung biopsy or resection has been suggested [42-45,50]. Prognosis of acute exacerbation is very poor with death occurring in the majority of patients within weeks or a few months [50,51]. However, survival has been reported in some cases and there is evidence that both histological and radiological patterns may provide a guide to the likely outcome [52,54,55]. Recurrence of acute exacerbation has been reported in some of the few survivors [50,55].

Histological examination in acute exacerbation shows patterns of acute lung injury on a background of typical UIP pattern. The cardinal acute lesion described is diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), but elements of organising pneumonia (OP) and numerous fibroblastic foci are also present [54]. Patients with OP or extensive fibroblastic foci seem to fare better than those with predominant DAD [51,54].

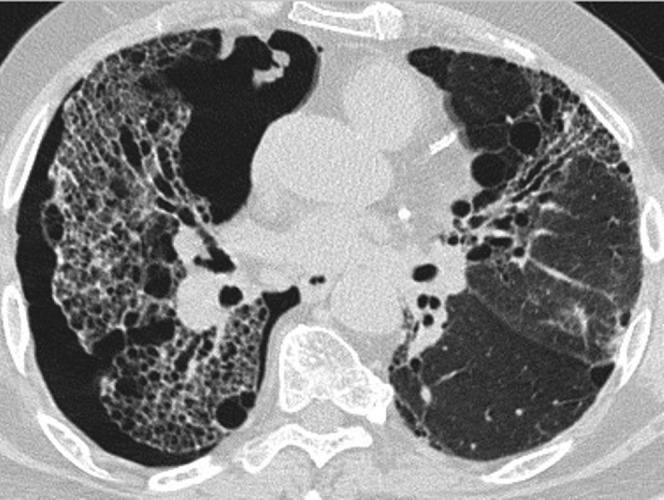

Three CT patterns of acute exacerbation of IPF have been described: peripheral, multifocal and diffuse parenchymal opacification (predominantly ground-glass opacity but sometimes consolidation), all occurring on a background of pre-existing fibrotic change typical of UIP/IPF [55] (Figure 6). Multifocal opacification with patchy involvement of both central and peripheral regions of lung parenchyma has been shown to progress to diffuse opacification in some cases, suggesting that the multifocal pattern may represent an earlier stage of acute exacerbation than the diffuse form [55]. The peripheral pattern does not appear to progress to diffuse opacification.

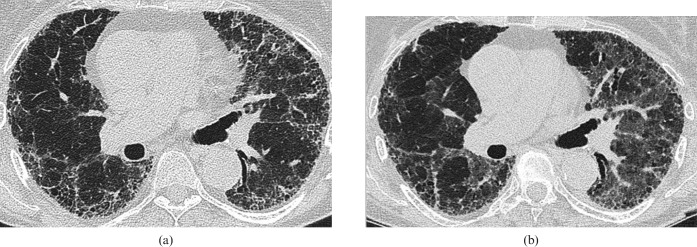

Figure 6.

Accelerated idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a 65-year-old man. (a) Base line high-resolution CT (HRCT) shows coarse subpleural reticulation with peripheral traction bronchiectasis and microcystic honeycombing. (b) HRCT 3 months later after a 2 week history of progressive breathlessness shows patchy ground-glass change superimposed on the reticular abnormality, and within the previously relatively normal lung parenchyma. Despite aggressive immunosuppressive therapy, the disease progressed inexorably and the patient died 3 weeks later.

Interestingly, the pattern and extent of parenchymal opacification may be related to outcome. Akira et al [55,56] found that patients with diffuse pattern on CT had a higher risk of death than those with a multifocal or peripheral pattern. The CT pattern and overall extent of disease on CT had a higher predictive value regarding patient survival than clinical and laboratory data, including baseline respiratory function tests, serum levels of C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase and white cell count [56]. In a study of acute exacerbation occurring in a range of chronic interstitial pneumonias (including IPF, idiopathic NSIP and fibrotic lung disease associated with collagen vascular disease), apparent better survival rates in peripheral (50% survival) and multifocal (40% survival) patterns compared with diffuse pattern (23% survival) did not reach statistical significance [51].

Treatment of acute exacerbation generally consists of high-dose steroids. Akira et al [55] found that all patients with peripheral pattern on HRCT at acute exacerbation showed resolution of opacities with corticosteroid treatment, whereas opacity persisted in all patients with a diffuse pattern despite corticosteroid treatment, with clinical deterioration and death occurring in all of these patients. The use of additional immunosuppression, including cyclosporin A [57], has been reported and there may be a role for the antifibrotic agent pirfenidone [58]. However, there are no data from randomised controlled trials to support the use of any specific treatment.

Acute exacerbation should be suspected in patients with IPF with extensive or rapidly progressive new ground-glass opacity on HRCT. The radiologist interpreting the HRCT of a patient with IPF and acute deterioration in symptoms should be familiar with the entity of acute exacerbation (Table 3) and the differential diagnosis of other conditions that may simulate acute exacerbation (Table 2).

Table 3. Acute exacerbation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

| Key points |

| Increasingly recognised as a common and often fatal complication of IPF |

| Histopathologically characterised by diffuse alveolar damage |

| CT patterns comprise widespread ground-glass opacification on a background of IPF/usual interstitial pneumonia |

| Peripheral pattern of opacification may have a better outcome than multifocal and diffuse patterns |

Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

Individuals with IPF have an increased prevalence of ischaemic heart disease. Kizer et al [59] found a significantly increased frequency of coronary artery disease detected at angiography in patients with end-stage fibrotic lung disease, including a subset with IPF, compared with patients with other end-stage lung diseases. Mortality and autopsy studies have reported cardiovascular causes of death in between a fifth and a quarter of patients with IPF [60,61]. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that cardiogenic pulmonary oedema is a common cause of acute deterioration in patients with IPF. The presence of profuse septal thickening on HRCT (an uncommon finding in uncomplicated IPF) with patchy ground-glass opacity and pleural effusions suggest cardiac failure as the cause of deterioration.

Infection

Bacterial, opportunistic (e.g. PCP) and viral respiratory infections may cause acute deterioration in patients with IPF and result in HRCT appearances that can be difficult to distinguish from those of acute exacerbation. Ideally, infection should be excluded as a cause of acute deterioration in IPF patients by endotracheal aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage [48].

Drug-induced pneumonitis

DAD is a common histopathological pattern of drug-induced lung injury, which manifests on HRCT as scattered or diffuse areas of ground-glass opacity [62]. This appearance may be indistinguishable from those of infection or acute exacerbation on a background of IPF. A large number of drugs are commonly associated with DAD [62,63], but of particular importance are those that may be used to treat IPF (e.g. cyclophosphamide), those drugs used to treat conditions associated with fibrosing lung disease (e.g. methotrexate and gold salts used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis). DAD has also been reported in patients receiving interferon gamma-1b as treatment for IPF, resulting in irreversible respiratory failure and death in four patients with severe IPF in one report [64]. However, a recent large multicentre placebo-controlled trial of interferon gamma-1b in IPF, while failing to show a survival benefit in the treatment arm, found that there was no significant difference in rate of pulmonary complications between the treatment and placebo arms [65]. As more immunomodulatory drugs are trialled in IPF in the future, drug-induced pneumonitis is likely to be increasingly recognised as a complication.

Pulmonary embolus

There is no definite link between IPF and pulmonary embolus (PE), but patients with IPF have an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis compared with age- and sex-matched controls [66], and PE appears more common after lung transplantation for IPF than for other lung diseases [67]. If there is a strong clinical suspicion of PE as a cause of acute deterioration in a patient with IPF, CT pulmonary angiography rather than HRCT should be performed. Not only does CT pulmonary angiography have excellent specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of PE [68], it often provides important ancillary diagnostic information in those patients who do not have PE [69]. An important caveat to this is that the presence of extensive fibrosis almost certainly reduces sensitivity of CTPA for the detection of subsegmental PEs. Additionally, CTPA performed in a patient with IPF and symptomatic deterioration makes evaluation of AE difficult owing to the unpredictable level of enhancement of the lung parenchyma (i.e. contrast enhancement of the parenchyma may mimic AE). In our experience, the positive yield of PE in patients with IPF and deterioration in symptoms is extremely low.

Pulmonary hypertension

PH is defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) >25 mmHg at rest in the presence of a normal left atrial pressure, and is a frequent and important complication of fibrotic lung disease. Studies have reported a prevalence of PH in 20–46% of patients with IPF undergoing work-up for lung transplantation [10,70,71], although the prevalence in the wider IPF population is less well documented. PH impacts adversely on morbidity and mortality in IPF, with a two to three-fold increase in mortality reported [10]. In patients with IPF, PH does not correlate with either restrictive lung physiology [10,72] or the extent of fibrosis at CT [72,73], suggesting it is not simply the destruction of the pulmonary vascular bed by progressive pulmonary fibrosis that leads to the development of PH and that other mechanisms, including vascular remodelling, are involved.

Right heart catheterisation (RHC) remains the gold standard diagnostic test for PH, but in view of its invasive nature and limited availability, reliable non-invasive methods of diagnosing PH are required. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TTE) is widely used to screen for PH by analysing tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity to provide an estimate of right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). However, in patients with chronic lung disease a poor acoustic window reduces the accuracy of TTE [74]. MRI using angiographic and cine techniques can provide information about pulmonary artery (PA) blood flow and right ventricular function, but its role is evolving and currently limited to specialist centres. In contrast, CT is routinely performed in patients suspected of having PH or in those with pulmonary diseases associated with PH. CT enables assessment of the pulmonary vasculature (specifically, measurement of vessel diameter) alongside the parenchyma, and a number of CT signs of PH have been reported.

Both the absolute size of the main PA [75,76] and the ratio of the PA diameter (dPA) to the diameter of the ascending aorta (dAA) [77] have been shown to correlate with mPAP. A dPA/dAA ratio of greater than one is highly specific for PH and may be more reliable than absolute PA size alone as it is less dependent on factors such as patient size and stage of the cardiac cycle [77]. Assessment of the dPA/dAA ratio has become a widely accepted quick and easy sign for the assessment of PH on CT.

However, two studies have shown that increased PA size may not be reliable for detecting PH in patients with fibrotic lung disease. Zisman et al [73] showed that there was no difference in PA diameter between patients with IPF and PH diagnosed at RHC and those with IPF but without PH. Devaraj et al [72] also found that PA diameter did not correlate with mPAP in a group of patients with fibrotic lung disease, while there was a correlation in a group with a range of non-fibrotic respiratory diseases. Nevertheless, a correlation between dPA/dAA ratio and mPAP was demonstrated in the pulmonary fibrosis group, suggesting this may still be a useful CT sign [72]. Segmental artery size has also been shown to correlate with mPAP, although not more closely than the main dPA/dAA ratio [78] (Figure 7). Recently, a composite index of CT and echocardiographic measurements (the dPA/dAA ratio and the RVSP, respectively) has been shown to correlate with mPAP better than either test in isolation [78]. The key CT signs of PH in IPF are summarised in Table 4.

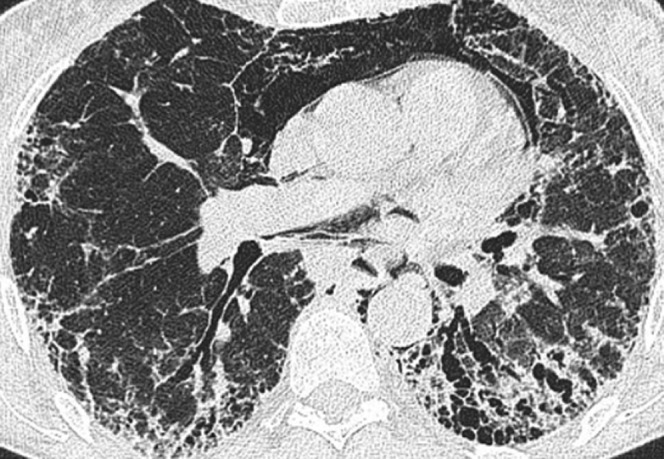

Figure 7.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in fibrotic lung disease. (a) In the setting of pulmonary fibrosis the absolute dimensions of the main pulmonary artery are not necessarily a reliable indicator of PAH. However, a main pulmonary artery (solid arrow) to ascending aorta (broken arrow) ratio of greater than one is a reliable CT sign of PAH, as in this case. (b) A segmental pulmonary artery (white arrow) diameter to segmental bronchus (arrowhead) diameter ratio greater than one also indicates raised pulmonary arterial pressure.

Table 4. Signs on CT for pulmonary hypertension (PH) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

| CT signs |

| Absolute pulmonary artery diameter is not a reliable sign of PH in patients with IPF |

| An increased ratio of pulmonary artery diameter to ascending aorta diameter of >1 remains a reliable indicator of PH in IPF |

| Increased segmental artery diameter may also signal PH |

| A composite assessment using CT and echocardiographic parameters is better than either test in isolation in estimating PH |

Miscellaneous complications of IPF

Pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum

Patients with chronic lung conditions, including fibrotic lung disease, are predisposed to developing spontaneous pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum [79]. Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in IPF maybe poorly tolerated and is therefore of diagnostic importance, whereas pneumomediastinum is often asymptomatic and an incidental imaging finding. Chest radiography may be negative for the detection of small amounts of extra-alveolar air on a background of complex parenchymal abnormalities in patients with IPF [79]. CT is more sensitive for the detection of pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax and better defines its extent and distribution (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8.

CT of spontaneous pneumothorax in a 55-year-old man with biopsy-proven usual interstitial pneumonia who presented with severe acute breathlessness.

Figure 9.

Pneumomediastinum in a man with advanced usual interstitial pneumonia.

Disseminated dendriform pulmonary ossification

Disseminated dendriform pulmonary ossification, a form of metaplastic mature bone formation in the lung parenchyma, is an unimportant and rare curiosity. It occurs in both normal and fibrotic lungs and is characterised by the presence of diffuse, branching bone spicules and distinguished histopathologically from the more common nodular type of disseminated pulmonary ossification that is associated with mitral stenosis [80,81].

Disseminated dendriform pulmonary ossification can be detected on HRCT (viewed on window settings appropriate for detection of calcification) as multiple tiny branching calcifications that do not conform to a recognisable anatomical or lobular configuration (Figure 10). One study found this appearance on HRCT in 5 out of 75 patients with UIP; this corresponded histopathologically to multiple dendriform nodules of mature bone embedded in fibrous stroma in basal, subpleural areas of fibrosis and honeycombing [82]. None of 44 patients with NSIP had HRCT or histopathological evidence of pulmonary ossification, and the authors suggest that, in the context of fibrotic lung disease, HRCT appearances compatible with disseminated dendriform pulmonary ossification may help distinguish UIP from NSIP [82].

Figure 10.

(a) Dendriform ossification in a 62-year-old man with fibrotic lung disease of unknown cause. There are numerous small punctate and branching dense opacities, mainly in fibrotic lung. (b) Oblique 5 mm maximum-intensity projection demonstrates the branching nature of the heterotopic bone formation within areas of fibrosis.

Conclusion

The diagnostic and prognostic role of HRCT in fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias is well documented. Many important and potentially treatable complications of fibrotic lung disease may be recognisable on HRCT. We have described the imaging appearances of these conditions, in particular infection, malignancy, acute exacerbation and PH. An awareness of these conditions and their appearances is important for the reporting radiologist.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International multidisciplinary consensus classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjoraker JA, Ryu JH, Edwin MK, Myers JL, Tazelaar HD, Schroeder DR, et al. Prognostic significance of histopathologic subsets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mapel DW, Hunt WC, Utton R, Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Coultas DB. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: survival in population based and hospital based cohorts. Thorax 1998;53:469–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbard R, Johnston I, Britton J. Survival in patients with cryptogenic fibrosis alveolitis: a population-based cohort study. Chest 1998;113:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson AG, Colby TV, du Bois RM, Hansell DM, Wells AU. The prognostic significance of the histologic pattern of interstitial pneumonia in patients presenting with the clinical entity of cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:2213–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, Starko KM, Bradford WZ, King TE, Jr, et al. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:963–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travis WD, Matsui K, Moss J, Ferrans VJ. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns. Survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noth I, Martinez FJ. Recent advances in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:637–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyzy R, Huang S, Myers J, Flaherty K, Martinez F. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:1652–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD, Barnett SD, Ahmad S, Shorr AF. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2006;129:746–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunninghake GW, Lynch DA, Galvin JR, Gross BH, Müller N, Schwartz DA, et al. Radiologic findings are strongly associated with a pathologic diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1215–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaherty KR, Thwaite EL, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Toews GB, Colby TV, et al. Radiological versus histological diagnosis in UIP and NSIP: survival implications. Thorax 2003;58:143–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch DA, Godwin JD, Safrin S, Starko KM, Hormel P, Brown KK, et al. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:488–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, King TE, Jr, Lynch J, Hegele R, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:193–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung MJ, Goo JM, Im JG. Pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur J Radiol 2004;52:175–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shachor Y, Schindler D, Siegal A, Lieberman D, Mikulski Y, Bruderman I. Increased incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in chronic interstitial lung disease. Thorax 1989;44:151–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sansom HE, Baque-Juston M, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Lateral cavity wall thickening as an early radiographic sign of mycetoma formation. Eur Radiol 2000;10:387–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraceno JL, Phelps DT, Ferro TJ, Futerfas R, Schwartz DB. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis: approach to management. Chest 1997;112:541–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidal S, de laHorra C, Martín J, Montes-Cano MA, Rodríguez E, Respaldiza N, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii colonisation in patients with interstitial lung disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:231–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yale SH, Limper AH. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: associated illness and prior corticosteroid therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reittner P, Ward S, Heyneman L, Johkoh T, Müller NL. Pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings in 114 patients. Eur Radiol 2003;13:515–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Lee KS, et al. Clinical significance of Mycobacterium fortuitum isolated from respiratory specimens. Respir Med 2008;102:437–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gefter WB. The spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. J Thorac Imaging 1992;7:56–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckingham SJ, Hansell DM. Aspergillus in the lung: diverse and coincident forms. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1786–1800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts CM, Citron KM, Strickland B. Intrathoracic aspergilloma: role of CT in diagnosis and treatment. Radiology 1987;165:123–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner-Warwick M, Lebowitz M, Burrows B, Johnson A. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and lung cancer. Thorax 1980;35:496–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubbard R, Venn A, Lewis S, Britton J. Lung cancer and cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. A population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Jeune I, Gribbin J, West J, Smith C, Cullinan P, Hubbard R. The incidence of cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Respir Med 2007;101:2534–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozawa Y, Suda T, Naito T, Enomoto N, Hashimoto D, Fujisawa T, et al. Cumulative incidence of and predictive factors for lung cancer in IPF. Respirology 2009;14:723–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aubry MC, Myers JL, Douglas WW, Tazelaar HD, Washington Stephens TL, Hartman TE, et al. Primary pulmonary carcinoma in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:763–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park J, Kim DS, Shim TS, Lim CM, Koh Y, Lee SD, et al. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2001;17:1216–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato T, Yamadori I, Fujita J, Hamada N, Yonei T, Bandoh S, et al. Three cases of non-specific interstitial pneumonia associated with primary lung cancer. Intern Med 2004;43:721–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniels CE, Jett JR. Does interstitial lung disease predispose to lung cancer? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2005;11:431–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raghu G, Nyberg F, Morgan G. The epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its association with lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2004;91S2:S3–S10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hironaka M, Fukayama M. Pulmonary fibrosis and lung carcinoma: a comparative study of metaplastic epithelia in honeycombed areas of usual interstitial pneumonia with or without lung carcinoma. Pathol Int 1999;49:1060–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee HJ, Im JG, Ahn JM, Yeon KM. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1996;20:979–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakai S, Ono M, Nishio T, Kawarada Y, Nagashima A, Toyoshima S. Lung cancer associated with diffuse pulmonary fibrosis: CT-pathologic correlation. J Thorac Imaging 2003;18:67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawai T, Yakumaru K, Suzuki M, Kageyama K. Diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. Acta Pathol Jpn 1987;37:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsushita H, Tanaka S, Saiki Y, Hara M, Nakata K, Tanimura S, et al. Lung cancer associated with usual interstitial pneumonia. Pathol Int 1995;45:925–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizushima Y, Kobayashi M. Clinical characteristics of synchronous multiple lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 1995;108:1272–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kishi K, Homma S, Kurosaki A, Motoi N, Yoshimura K. High-resolution computed tomography findings of lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2006;30:95–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar P, Goldstraw P, Yamada K, Nicholson AG, Wells AU, Hansell DM, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: Risk and benefit analysis of pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:1321–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe A, Higami T, Ohori S, Koyanagi T, Nakashima S, Mawatari T. Is lung cancer resection indicated in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;136:1357–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawasaki H, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Nishiwaki Y. Postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival in lung cancer associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Surg Oncol 2002;81:33–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kushibe K, Kawaguchi T, Takahama M, Kimura M, Tojo T, Taniguchi S. Operative indications for lung cancer with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;55:505–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda A, Enomoto T, Sanuki N, Nakajima T, Takeda T, Sayama K, et al. Acute exacerbation of subclinical idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis triggered by hypofractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy in a patient with primary lung cancer and slightly focal honeycombing. Radiat Med 2008;26:504–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kudoh S, Kato H, Nishiwaki Y, Fukuoka M, Nakata K, Ichinose U, et al. Interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with lung cancer: A cohort and nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:1348–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Kaner RJ, King TE, Jr, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:636–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernández Pérez ER, Daniels CE, Schroeder DR, St. Sauver J, Hartman TE, Bartholmai BJ, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A population-based study. Chest 2010;137:129–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim DS, Park JH, Park BK, Lee JS, Nicholson AG, Colby T. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: frequency and clinical features. Eur Respir J 2006;27:143–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silva CI, Müller NL, Fujimoto K, Kato S, Ichikado K, Taniguchi H, et al. Acute exacerbation of chronic interstitial pneumonia: High-resolution computed tomography and pathologic findings. J Thorac Imaging 2007;22:221–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park IN, Kim DS, Shim TS, Lim CM, Lee SD, Koh Y, et al. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:214–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olson AL, Huie TJ, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, Janssen WJ, Schwarz MI, et al. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: A case series. Chest 2008;134:844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Churg A, Müller NL, Silva CI, Wright JL. Acute exacerbation (acute lung injury of unknown cause) in UIP and other forms of fibrotic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:277–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akira M, Hamada H, Sakatani M, Kobayashi C, Nishioka M, Yamamoto S. CT findings during phase of accelerated deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akira M, Kozuka T, Yamamoto S, Sakatani M. Computed tomography findings in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:372–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Homma S, Sakamoto S, Kawabata M, Kishi K, Tsuboi E, Motoi N, et al. Cyclosporin treatment in steroid-resistant and acutely exacerbated interstitial pneumonia. Intern Med 2005;44:1144–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Azuma A, Nukiwa T, Tsuboi E, Suga M, Abe S, Nakata K, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1040–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kizer JR, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, Kotloff RM, Kimmel SE, Strieter RM, et al. Association between pulmonary fibrosis and coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:551–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daniels CE, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Autopsy findings in 42 consecutive patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2008;32:170–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Panos RJ, Mortenson RL, Niccoli SA, King TE., Jr Clinical deterioration in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Causes and assessment. Am J Med 1990;88:396–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rossi SE, Erasmus JJ, McAdams HP, Sporn TA, Goodman PC. Pulmonary drug toxicity: Radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Radiographics 2000;20:1245–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hansell DM, Lynch DA, McAdams HA, Bankier AA. Imaging of diseases of the chest. 5th ed. Elsevier, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Honoré I, Nunes H, Groussard O, Kambouchner M, Chambellan A, Aubier M, et al. Acute respiratory failure after interferon-γ therapy of end stage pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:953–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.King TE, Jr, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Hormel P, Lancaster L, et al. Effect of interferon gamma-1b on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (INSPIRE): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374:222–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hubbard RB, Smith C, Le Jeune I, Gribbin J, Fogarty AW. The association between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and vascular disease: A population-based study. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2008;178:1257–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nathan SD, Barnett SD, Urban BA, Nowalk C, Moran BR, Burton N. Pulmonary embolism in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis transplant recipients. Chest 2003;123:1758–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayo JR, Remy-Jardin M, Müller NL, Remy J, Worsley DF, Hossein-Foucher C, et al. Pulmonary embolism: prospective comparison of spiral CT with ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy. Radiology 1997;205:447–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim KI, Müller NL, Mayo JR. Clinically suspected pulmonary embolism: Utility of spiral CT. Radiology 1999;210:693–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.King TE, Jr, Tooze JA, Schwarz MI, Brown KR, Cherniack RM. Predicting survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: scoring system and survival model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:1171–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shorr AF, Wainright JL, Cors CS, Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with pulmonary fibrosis awaiting lung transplant. Eur Respir J 2007;30:715–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Corte TJ, Hansell DM. The effect of diffuse pulmonary fibrosis on the reliability of CT signs of pulmonary hypertension. Radiology 2008;249:1042–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zisman DA, Karlamangla AS, Ross DJ, Keane MP, Belperio JA, Saggar R, et al. High-resolution chest CT findings do not predict the presence of pulmonary hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:773–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, Sutton MS, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:735–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuriyama K, Gamsu G, Stern RG, Cann CE, Herfkens RJ, Brundage BH. CT-determined pulmonary artery diameters in predicting pulmonary hypertension. Invest Radiol 1984;19:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Edwards PD, Bull RK, Coulden R. CT measurement of main pulmonary artery diameter. Br J Radiol 1998;71:1018–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ng CS, Wells AU, Padley SP. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging 1999;14:270–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Corte TJ, Wort SJ, Hansell DM. Detection of pulmonary hypertension with multidetector CT and echocardiography alone and in combination. Radiology 2010;254:609–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Franquet T, Giménez A, Torrubia S, Sabaté JM, Rodriguez-Arias JM. Spontaneous pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum in IPF. Eur Radiol 2000;10:108–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mendeloff J. Disseminated nodular pulmonary ossification in the Hamman-Rich lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1971;103:269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fried ED, Godwin TA. Extensive diffuse pulmonary ossification. Chest 1992;102:1614–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim TS, Han J, Chung MP, Chung MJ, Choi YS. Disseminated dendriform pulmonary ossification associated with usual interstitial pneumonia: incidence and thin-section CT-pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol 2005;15:1581–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]