Abstract

We describe the case of a 32-year-old woman with pulmonary tuberculosis in whom a high-resolution CT scan demonstrated the reversed halo sign. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was made by lung biopsy and the detection of acid-fast bacilli in the sputum smear and culture. Follow-up assessment revealed a significant improvement in the lesions.

The reversed halo sign is observed on high-resolution CT (HRCT) as a focal round area of ground-glass attenuation surrounded by a crescent or ring of consolidation [1, 2]. It was first described as being relatively specific for cryptogenic organising pneumonia [1], but was later observed in several other infectious [3–5] and non-infectious [6, 7] diseases.

We report a case of a 32-year-old patient with tuberculosis who exhibited the reversed halo sign on chest CT. To our knowledge, this sign has not been previously described in an adult with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Case report

A 32-year-old black woman presented to the pneumology department with a three week history of dry cough. She denied dysponea, fever, night sweats or haemoptysis, but reported a 3 kg weight loss in the previous month. The patient also had a 38 pack-year history, although there was no history of alcohol or drug abuse. She took no medications and had no known occupational exposure to organic or inorganic substances, or to tuberculosis. As the patient presented with abnormalities on her chest radiograph, she was admitted for investigation.

Physical examination at the time of admission revealed a chronically ill-appearing woman who was afebrile; her vital signs were normal, with no palpable lymph nodes. Pulmonary auscultation showed diffuse bilateral crackles. Cardiovascular and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. Laboratory investigations included a normal complete blood cell count, fasting blood glucose (84 mg dl−1) and lactate dehydrogenase (207 U l−1). Liver function tests were also within the normal range. Tests for rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies were negative, as were the fungal and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies.

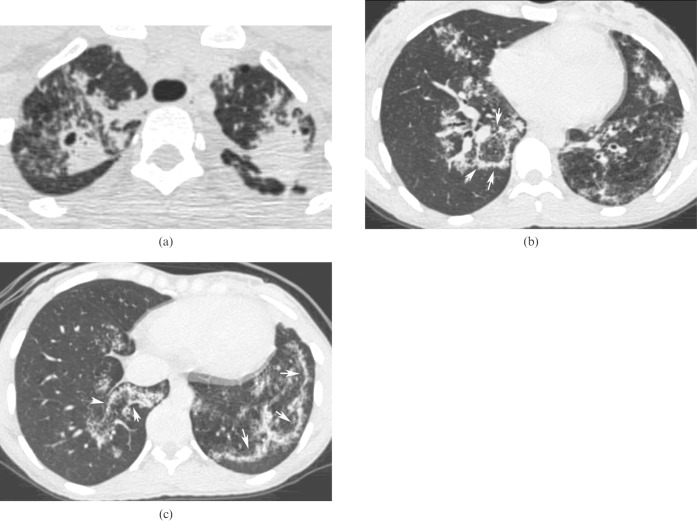

The initial chest radiograph demonstrated small ill-defined nodules and airspace opacities distributed throughout the lung parenchyma. There was no lymph node enlargement. HRCT revealed cavitated areas of consolidation in both the upper lobes, bronchial wall thickening, and small nodules throughout the lungs. Areas of ground-glass opacities surrounded by parenchymal consolidation (reversed halo sign) were also present (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A high-resolution CT scan showing patchy consolidations and ground-glass opacities in both lungs, with a cavitation in the right upper lobe (a). Opacities with central areas of ground-glass attenuation surrounded by denser crescentic consolidations of at least 2 mm thickness (reversed halo sign; arrows) are seen in the lower lobes (b,c). These areas are admixed with poorly defined nodules. No lymphadenopathy is evident.

As the patient had no expectoration, three bronchoalveolar lavages were performed: all samples were smear negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), bacteria and fungi, as were the bacterial cultures. Bronchofibroscopy did not show any endobronchial lesions, and the transbronchial biopsy specimen was negative. The patient underwent an open biopsy of the lingular segment of the lung, and pathology revealed the presence of tuberculoid granulomas within areas of suppuration and fibrosis. Stains for AFB and fungi were negative.

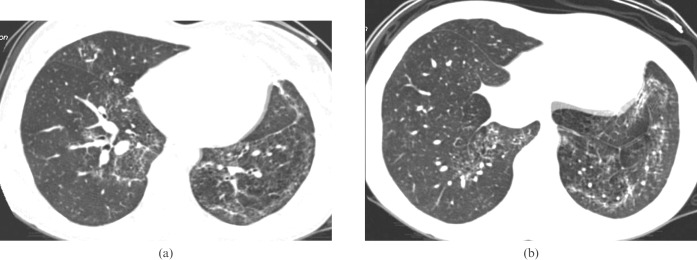

Following surgery, the patient began to expectorate copious amounts of secretion. A sputum sample was collected and the AFB smear was positive. Culture was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A three-drug regimen of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide was initiated. Follow-up HRCT, three months after treatment, showed significant improvement of the lesions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A follow-up high-resolution CT scan, obtained three months after the first examination with scans of the same level of Figure 1b (a) and Figure 1c (b), shows significant improvement in the opacities.

Discussion

Voloudaki et al [2] described the CT findings of two patients with cryptogenic organising pneumonia that manifested as central ground-glass opacities (corresponding to alveolar septal inflammation and cellular debris in the alveolar spaces) surrounded by a more solid ring- or crescent-shaped airspace consolidation (corresponding to granulomatous tissue in the peripheral air spaces). In a study of 31 patients with cryptogenic organising pneumonia, Kim et al [1] observed similar findings in 19% of patients and named this feature the “reversed halo sign”. The authors examined the incidence of this sign in diseases with similar radiological characteristics, and found that the reversed halo sign could not be seen in any of these other diseases. They concluded that the sign was sufficiently specific to establish a diagnosis of cryptogenic organising pneumonia [1, 3, 7].

Although initially thought to be specific for cryptogenic organising pneumonia [1, 2], the reversed halo sign has since been described in other disorders. These include organising pneumonia secondary to various diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, breast cancer and lipoid pneumonia) [8, 9], pulmonary zygomycosis [10], pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis [3], pulmonary tuberculosis [5], lymphomatoid granulomatosis [7], and small vessel vasculitis (Wegener's granulomatosis) [6]. The reversed halo sign thus appears to be non-specific and is encountered in various pulmonary disorders [6].

The reversed halo should not be confused with the “computed tomography (CT) halo sign” or the “fairy ring sign” seen on HRCT. The “CT halo sign” in a pulmonary nodule refers to an area of ground-glass attenuation surrounding a pulmonary nodule [11]. The “fairy ring sign”, in turn, has been described in sarcoidosis, in which central areas of the lesion comprise normal lung tissue. It is speculated that fairy ring lesions are formed by central granulomatous inflammation which has spontaneously resolved while new granulomatous lesions appear at the periphery [12].

The HRCT findings from post-primary tuberculosis patients include centrilobular or airspace nodules and branching linear structures (tree-in-bud pattern), consolidations, cavitations, bronchial wall thickening, miliary nodules, tuberculomas, calcifications, parenchymal bands, interlobular septal thickening, ground-glass opacities, pericicatricial emphysema, and fibrotic changes [13, 14]. To our knowledge, only one case of a reversed halo sign in tuberculosis has been previously described [5]. Unlike our patient, this earlier study reported a case of a 15-year-old boy who showed subcarinal and left hilar lymphadenopathy, in addition to the parenchymal findings. In our case, the patient was an adult female who exhibited cavitated areas of consolidation, along with nodules and opacities with the reversed halo sign. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Although the HRCT findings in the lingula (where the biopsy was performed) were similar to other areas in the lung, it is possible that the reverse halo sign was a result of organising pneumonia reaction pattern to tuberculosis rather than a direct manifestation of tuberculosis.

In conclusion, we show that pulmonary tuberculosis may present as the reversed halo sign on HRCT in adult patients.

References

- 1.Kim SJ, Lee KS, Ryu YH, Yoon YC, Choe KO, Kim TS, et al. Reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: diagnostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180:1251–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voloudaki AE, Bouros DE, Froudarakis ME, Datseris GE, Apostolaki EG, Gourtsoyiannis NC. Crescentic and ring-shaped opacities. CT features in two cases of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Acta Radiol 1996;37:889–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasparetto EL, Escuissato DL, Davaus T, de Cerqueira EM, Souza AS, Jr, Marchiori E, et al. Reversed halo sign in pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:1932–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahba H, Truong MT, Lei X, Kontoyiannis DP, Marom EM. Reversed halo sign in invasive pulmonary fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1733–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja A, Gothi D, Joshi JM. A 15 year-old boy with reversed halo. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2007;49:99–101 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal R, Agarwal AN, Gupta D. Another cause of reverse halo sign: Wegener's granulomatosis. Br J Radiol 2007;80:849–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benamore RE, Weisbrod GL, Hwang DM, Bailey DJ, Pierre AF, Lazar NM, et al. Reversed halo sign in lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Br J Radiol 2007;80:e162–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanaji N, Bandoh S, Nagamura N, Chang SS, Ishikawa S, Yokomise H, et al. Lipoid pneumonia showing multiple pulmonary nodules and reversed halo sign. Respir Med Extra 2007;3:98–101 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bravo Soberón A, Torres Sánchez MI, García Río F, Sánchez Almaraz C, Parrón Pajares M, Pardo Rodríguez M. High-resolution computed tomography patterns of organizing pneumonia. Arch Bronconeumol 2006;42:413–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raoof S, Raoof S, Naidich DP. Imaging of unusual diffuse lung diseases. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:383–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008;246:697–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marlow TJ, Krapiva PI, Schabel SI, Judson MA. The “fairy ring”: a new radiographic finding in sarcoidosis. Chest 1999;115:275–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatipoğlu ON, Osma E, Manisali M, Uçan ES, Balci P, Akkoçlu A, et al. High resolution computed tomographic findings in pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax 1996;51:397–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Lee KS, Jung KJ, Han J, Kwon OJ, Kim J, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis: CT and pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2000;24:691–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]