Abstract

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare manifestation in patients with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis (AS). We report a 57-year-old male patient with a 30-year history of AS who developed CES in the past 4 years. The CT and MRI examinations showed unique appearances of dural ectasia, multiple dorsal dural diverticula, erosion of the vertebral posterior elements, tethering of the conus medullaris to the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal and adhesion of the nerve roots of the cauda equina to the wall of the dural sac. A large dural defect was found at surgery. De-adhesion of the tethered conus medullaris was performed but without significant clinical improvement. The possible aetiologies of CES and dural ectasia in patients with chronic AS are discussed and the literature is reviewed.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a seronegative spondyloarthropathy primarily affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints. Neurological sequela is usually accompanied by atlantoaxial subluxation with spinal cord compression or pathological fracture of the rigid spine at cervicothoracic or thoracolumbar junctions even after a minor traumatic event [1]. Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare neurological manifestation in patients with long-standing AS (also called CES-AS syndrome) and was first reported by Bowie and Glasgow [2], and Hauge [3] in 1961. Dural ectasia is a condition in which the spinal dural sac is enlarged usually involving the lumbosacral regions where the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure is greatest [4]. It is occasionally seen in patients with Marfan syndrome, neurofibromatosis Type I, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and long-standing AS. However, the bony erosion in AS predominantly involves the posterior elements rather than the posterior aspect of vertebral bodies seen in the other conditions [5]. The mechanism of CES and dural ectasia in patients with AS is still not clear. We present a case of CES-AS syndrome. The clinical findings, imaging features, surgical and pathological results support the theory of a chronic inflammatory process.

Case report

A 57-year-old male patient with a 30-year history of AS had started to experience gradual onset of tingling, numbness, weakness and muscle atrophy in the bilateral lower limbs and saddle region for the past 4 years, and finally had to use a walker. He also complained of frequent constipation and urinary retention requiring periodic urinary self-catheterisation. His muscle strength grading was two in the right lower limb and three in the left lower limb (based on the Medical Research Council scale) with decreased deep tendon reflex. Laboratory results revealed anaemia (haemoglobin 10.6 mg dl–1) and urinary tract infection. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) and electromyography (EMG) examinations showed bilateral lumbosacral radiculopathy, predominant motor polyneuropathy and disuse myopathy in the lower limbs. He was admitted with suspected CES.

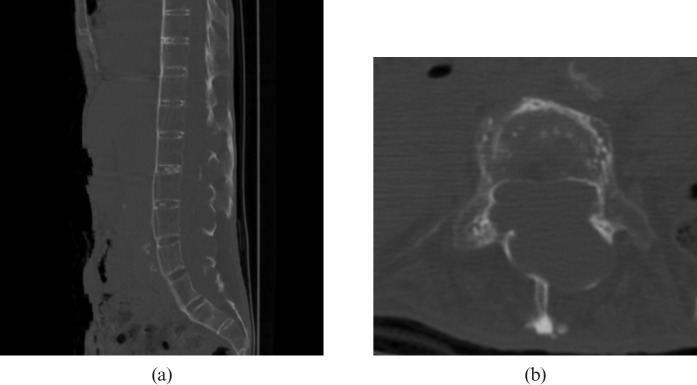

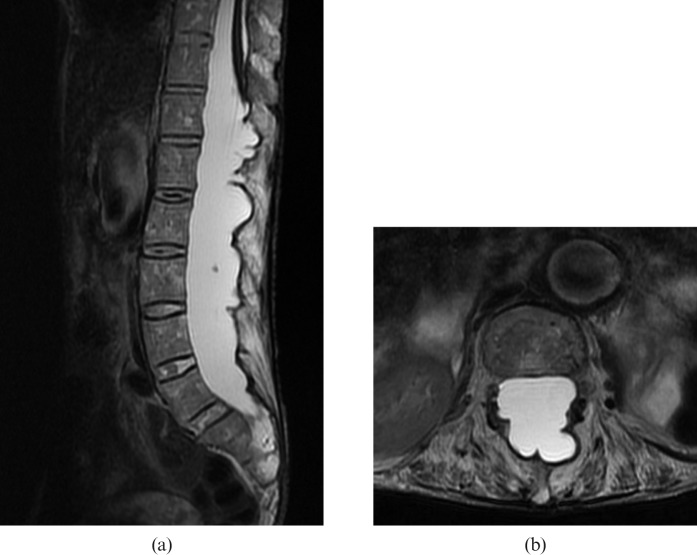

A CT scan showed flowing ossification of the paraspinous ligaments, fusion of the facet joints and squaring of the vertebral bodies producing a “bamboo spine” appearance typical of AS (Figure 1). Also noted was the expansion of the spinal canal with remodelling and erosion of the posterior elements of the vertebrae including the pedicles, laminae and spinous processes from level T12 to S1. The MRI examination of the lumbar spine revealed dural ectasia with multiple dorsal dural diverticula at the same level (Figure 2). The conus medullaris was tethered to the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal at T12 level and the nerve roots of the cauda equina were adherent to the wall of the dural sac, which produced an “empty dural sac” sign.

Figure 1.

(a) Sagittal reconstructed CT scan of the abdomen on bone window setting shows flowing ossification of the paraspinous ligaments and squaring of the vertebral bodies producing a “bamboo spine” appearance typical for ankylosing spondylitis. (b) Axial CT scan focused on the L4 vertebra shows expansion of the spinal canal with remodelling and erosion of the posterior elements of the vertebrae including the pedicles, laminae and spinous process.

Figure 2.

(a) Sagittal fast-spin echo T2 weighted MRI (repetition time (TR)/ echo time (TE) = 2800/110) shows dural ectasia with multiple dorsal dural diverticula from level T12 to S1. The conus medullaris was tethered to the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal at T12 level. (b) Axial fast-spin echo T2 weighted MRI (TR/TE = 9600/111) at L3 level shows adhesion of the nerve roots of the cauda equina to the wall of the dural sac, producing an “empty dural sac” sign.

An operation of laminectomy at T12 vertebra and de-adhesion of the conus medullaris was carried out to release the tension from nerve root stretch. On operating, a large dural defect was found at the dorsal aspect of the dural sac at T12 level. The conus medullaris was separated from the adhesion site. The dural defect was repaired with autofascia and duraform. The pathology of a section of the meningeal membrane showed dense fibrous tissues with ossification and scanty lymphoplasma cell infiltration that was consistent with a chronic inflammatory process. The patient's cauda equina syndrome did not improve after the operation.

Discussion

The mechanism of dural ectasia and dural diverticula formation in patients with long-standing AS is still not clear. A possible theory is that the meninges and the dural sac expand promptly in response to the CSF pulse pressure under normal conditions, allowing absorption of CSF and dampening of the transmitted pressure variations. In patients with long-standing AS, the inflammatory process may extend from the paraspinous ligaments to the dural matter, resulting in adhesion of the dural matter to the surrounding structures that reduce the compliance and elasticity of the lower dural sac and its ability to dampen the fluctuations in CSF pressure [3,6,7]. The inflamed dura matter may be weakened, further encouraging the development of dural ectasia and bony erosion. In our case, a large dural defect was found in surgery and the pathological findings showed chronic inflammation of the meninges, which is compatible with this theory.

There are several possible mechanisms of CES–AS syndrome, including small vessel angiitis involving the vasa vasorum of the nerve roots, previous spinal irradiation for treatment of AS, nerve root damage owing to dural ectasia with decreased elasticity of the dural sac and increased arterial pulsatile forces transmitted through the CSF, and chronic inflammatory process [6,7,8]. However, most reported cases including our patient did not have a history of spinal irradiation. The inflammatory process may spread from the peridural soft tissues to the nerve roots of the cauda equina, which in turn causes arachnoiditis and CES [3,7]. Our patient's clinical course showed slowly progressive sensory and motor disorders in the bilateral lower limbs and saddle region as well as bowel and urinary bladder dysfunction. The NCV and EMG revealed lumbosacral radiculopathy, polyneuropathy and disuse myopathy in the bilateral lower limbs. The MRI also showed tethering of the conus medullaris to the dorsal aspect of the spinal canal and adhesion of the nerve roots of the cauda equina to the wall of the dural sac, suggesting an adhesive arachnoiditis. All of the above findings are consistent with the chronic inflammatory theory of CES–AS syndrome, which usually develops between 17 and 53 years (average, 35 years) after the onset of AS [9,10].

There is no effective medical or surgical treatment for dural ectasia, presumably an end result of the chronic inflammatory process. Ahn et al [11] performed a meta-analysis study on the treatment effect of CES–AS syndrome. They found steroids are not effective in the chronic stage, while non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) decrease back pain but do not improve neurological deficit, probably owing to no active inflammation in the chronic stage of CES–AS syndrome. Lan et al [12] reported a case with partial clinical improvement after intrathecal injection of methotrexate and decadron, and lumboperitoneal (LP) shunting. The CSF study (lymphocytosis and elevated protein level) and MRI features (acute transverse myelitis and enhancement of the leptomeninges) in their case suggested an acute episode of inflammation. Cornec et al [13] also reported a case with dramatic clinical improvement in anal sphincter function and sensation at anus and buttocks after treated with infliximab, a monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor α (a major pro-inflammatory cytokine) that is used for the treatment of active AS. Surgical intervention, such as LP shunting or laminectomy may improve or arrest the progress of pain, sensory, motor, bowel and bladder dysfunction in a few patients based on the theory of attributing nerve root damage to excessive pulse pressure in CSF and to nerve root compression from the dural diverticula [6,12,14-16]. However, some reported cases, including our patient, revealed limited or no clinical improvement after surgical treatment, and this theory is still controversial [11]. Arslanoglu et al [17] proposed a combined theory that an initial inflammatory process results in adhesion of the nerve roots of the cauda equina to the dural sac, and the nerve roots are progressively stretched by the enlarging diverticula. We assume that the effect of medical and surgical treatments may be determined on the timing of the intervention, whether there is active inflammation or irreversible nerve root damage has developed, such as in our case. MRI and CSF studies may provide valuable information in the diagnosis and treatment planning in patients with CES–AS syndrome.

References

- 1.Westerveld LA, Verlaan JJ, Oner FC. Spinal fractures in patients with ankylosing spinal disorders: a systemic review of the literature on treatment, neurological status and complications. Eur Spine J 2009;18:145–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowie EA, Glascow GL. Cauda equine lesions associated with ankylosing spondylitis: report of three cases. Br Med J 1961;2:24–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauge T. Chronic rheumatoid polyarthritis and spondyl-arthritis associated with neurological symptoms and signs occasionally simulating an intraspinal expansive process. Acta Chir Scand 1961;120:395–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tallroth K, Malmivaara A, Laitinen ML, Salvolainen A, Harilainen A. Lumbar spine in Marfan syndrome. Skeletal Radiol 1995;24:337–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nallamshetty L, Ahn NU, Ahn UM, Nallamshetty HS, Rose PS, Buchowski JM, et al. Dural ectasia and back pain: review of the literature and case report. J Spinal Disord Tech 2002;15:326–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Confavreux C, Larbre JP, Lejeune E, Sindou M, Aimard G. Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in the tardive cauda equine syndrome of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Neurol 1991;29:221–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthews WB. The neurological complications of ankylosing spondylitis. J Neurol Sci 1991;29:221–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soeur M, Monseu G, Baleriaux-Waha D, Duchateau M, Williame E, Pasteels JL. Cauda equine syndrome in ankylosing spondylitis: anatomical, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1981;55:303–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein DJ, Alvarez O, Ghelman B, Marchisello P. Cauda equine syndrome complicating ankylosing spondylitis: MR features. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;13:511–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartleson JD, Cohen MD, Harrington TM, Goldstein NP, Ginshurg WW. Cauda equine syndrome secondary to long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Neurol 1983;14:662–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn NU, Ahn UM, Nallamshetty L, Springer BD, Buchowski JM, Funches L, et al. Cauda equine syndrome in ankylosing spondylitis (the CES-AS syndrome): meta-analysis of outcomes after medical and surgical treatments. J Spinal Disord 2001;14:427–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan HH, Chen DY, Chen CC, Lan JL, Hsieh CW. Combination of transverse myelitis and arachnoiditis in cauda equina syndrome of long-standing ankylosing spondylitis: MRI features and its role in clinical imaging. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:1963–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornec D, Pensec VD, Joulin SJ, Saraux A. Dramatic efficacy of Infliximab in cauda equine syndrome complicating ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1657–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larner AJ, Pall HS, Hockley AD. Arrested progression of the cauda equina syndrome of ankylosing spondylitis after lumboperitoneal shunting. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:115–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw PJ, Allcutt DA, Bates D, Crawford PJ. Cauda equina syndrome with multiple lumbar arachnoid cysts in ankylosing spondylitis: improvement following surgical therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990;53:1076–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinichert A, Cornelius JF, Lot G. Lumboperitoneal shunt for treatment of dural ectasia in ankylosing spondylitis. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:1179–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arslanoglu A, Aygun N. Magnetic resonance imaging of cauda equina syndrome in long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Australas Radiol 2007;51:375–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]