Abstract

We report a case of congenital abnormality of bicornuate bicollis uterus in a patient who developed FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage IIB invasive carcinoma of the cervix in 2006. She was managed with radical concurrent chemoradiotherapy using an external photon beam of 50 Gy in 25 fractions and a weekly infusion of cisplatin, followed by low dose rate intracavity brachytherapy of 18 Gy to Manchester point A over two fractions. Intra-uterine afterloading brachytherapy catheters were inserted into both uterine cavities. Treatment was well tolerated with manageable acute toxicities. Complete response was achieved with therapy. The patient remains well on follow up with no clinical evidence of disease recurrence two years after initial treatment.

Case history

A 45-year-old woman was referred to the Northern Gynaecological Centre in 1993 with cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3 on cervical screening. She had experienced persistent mild dyskaryosis since 2001. In 2006, a repeat cervical smear showed moderate dyskaryosis. Colposcopic examination revealed a high-grade lesion suspicious of malignancy, probably a vaginal intra-epithelial neoplasia on the posterior and lateral vaginal walls. She underwent large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ). Histology confirmed CIN3 and moderately differentiated keratinising squamous cell carcinoma 20 mm wide and up to 10 mm deep. No lymphovascular space invasion was identified. However, biopsies taken from the vaginal wall showed no evidence of malignancy.

Examination under anaesthesia with cystoscopy was performed on 6 September 2006. This examination revealed a barrel-shaped cervix with a large, 5 cm cervical tumour and scarring of the right vaginal angle, but no tumour on the vaginal wall. There was also slight thickening of the right parametrium. Cystoscopy was normal. Clinical FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage was 2A.

After a pelvic MRI scan performed on the 29 August 2006, it was noted that the woman has a bicornuate bicollis uterus (Figure 1). There was a tumour present involving both cervices, though predominantly the right of the cervix. The cervical tumour measured 50 mm × 40 mm × 23 mm. The cervical stroma was breeched from 6 o'clock to 9 o'clock and although no macroscopic parametrial extension was evident, there was probably microscopic spread on the right. The tumour extended into the upper vagina, probably just the upper third. There was no extension into the corpus. There was no disruption of the vaginal wall and the bladder and rectum were not involved. No enlarged lymph nodes were noted and there was no hydronephrosis or hydroureter. Incidentally, the scan also showed multiple fibroids, with the largest being a 2.4-cm subserosal lesion arising from the ventral surface.

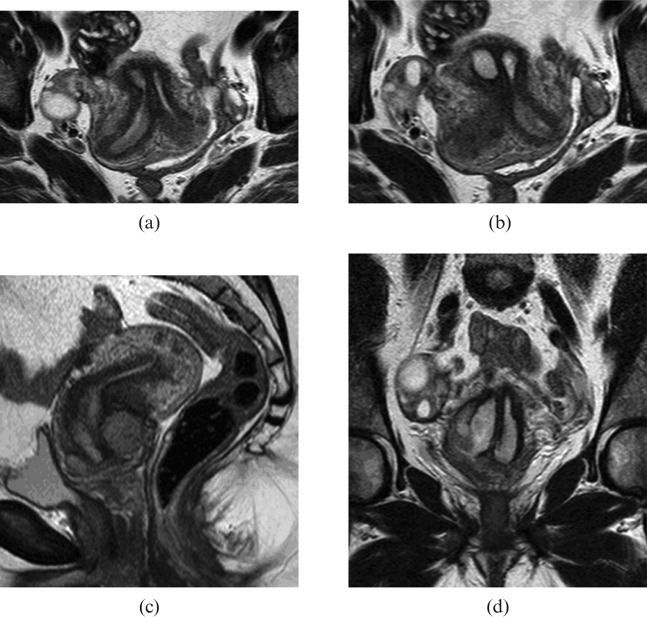

Figure 1.

T2 weighted MRI images of the pelvis. (a) and (b) Cross-section slices through cervices and uterine cavities. (c) Sagittal slice through cervix and uterus with bulky tumour at the cervix extending into the upper vagina. (d) Coronal slice through tumour with view of both uterine cavities and septum.

The woman is very fit and well with no significant past medical problems or regular medication. She is in a stable heterosexual relationship and is nulliparous. She is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack-year history and drinks little alcohol.

Radiotherapy

The woman was treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Using a 4-field technique, the pelvis was treated with 15 MV photons, 50 Gy in 25 daily 2-Gy fractions prescribed to the 100% isodose (Figure 2). External beam photon therapy was given over 32 days. She also received 5 weekly cisplatin infusions at a dose of 40 mg m−2 (max. 70 mg). Treatment was given without interruption. The glomerular filtration rate prior to the first cycle of chemotherapy was measured at 118 ml min−1. The haemoglobin level was maintained well above 12 g dl−1 throughout treatment without support. She tolerated treatment well, apart from developing grade 1 diarrhoea, requiring loperamide, with external beam therapy.

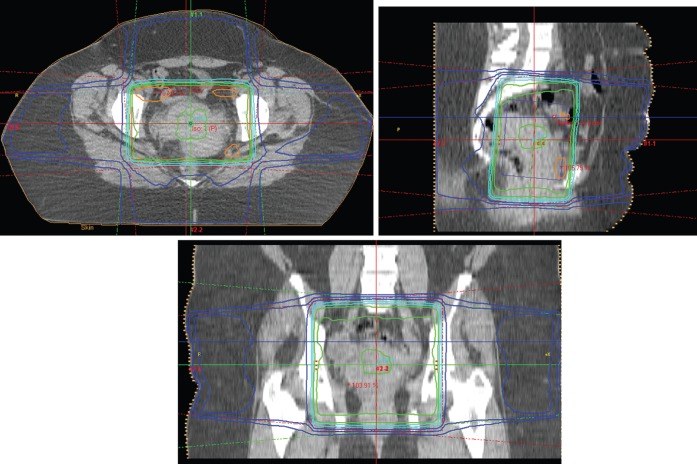

Figure 2.

Four-field radiotherapy technique for external photon beam treatment. Field localisation was done with CT simulation.

An examination under anaesthesia was repeated midway through external radiation treatment to assess tumour response. Both cervices were easily identified. The parametrium was not fixed and minimal thickening was palpable on the right. There was good tumour response.

Intracavitary brachytherapy was given with low dose rate caesium-137 delivered via a Nucletron Selectron (Chester, UK) remote afterloading machine. The prescription was 18 Gy over two fractions to the Manchester A points. The applicator was a 3 cm diameter Perspex vaginal cylinder with a tungsten rectal shield. The source train extended from within the centre of the Perspex applicator into a flexible interuterine catheter [1].

For fraction 1, the interuterine catheter was inserted into the right uterine canal and a radio-opaque marker inserted into the left uterine canal. Co-ordinates were reconstructed from CT images. The right Manchester A point was calculated as tilted with the angulated interuterine source train [1]. The left Manchester A point was calculated as tilted with the angulated radio-opaque marker in the contralateral uterine canal. This process was repeated for the opposite canals on the second fraction (Figure 3). From the position of the active sources and the marker wire on fraction 1, a prediction was made of the total dose from both fractions. Fraction 1 was delivered so that if the geometry was maintained for fraction 2 the total dose would be an average of 18 Gy to both A points. The geometry was revised on fraction 2 and the remaining treatment delivered to optimise the dose points.

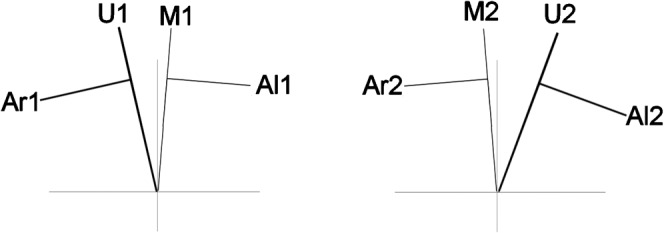

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic representation of positions of right and left A points as determined from CT data. Fraction 1 (a), fraction 2 (b). U represents an active interuterine tube. M represents a marker wire. A points are drawn with a perpendicular at 2 cm to define the points of their respective positions for each fraction.

Physical doses to the left and right A points, the pelvic lymph nodes and vaginal wall were summated. These are reported in the discussion. Radiobiological summation was also performed as a safety check before fraction 2, since the asymmetry of the treatment led to different dose rates at each calculation point between fractions 1 and 2.

Follow-up

The patient was reviewed every three months following completion of treatment. She was commenced on hormone replacement treatment to control post-menopausal symptoms and to prevent complications related to premature ovarian failure. It is recommended that she is on HRT until the age of 50 years. Eight months following radiotherapy, the patient experienced intermittent cystitis, haematuria and slight per rectal fresh bleeding. These symptoms were managed conservatively. She was last reviewed on 7 November 2008, and there was no evidence of disease recurrence.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is one of the most common female cancers worldwide. It accounts for 1 in 10 female cancers diagnosed. Approximately 2800 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in the United Kingdom in 2005, making it the twelfth most common cancer in women [2]. The Incidence rate of cervical cancer peaks in the third and fourth decades.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histological subtype. There is strong evidence suggesting human papilloma virus (HPV) plays a central role, with types 16, 18, 31 and 33 linked to the development of cervical cancer [3, 4]. Viral DNA is integrated into the host genome resulting in the production of oncoproteins E6 and E7. E6 oncoprotein interferes with P53 and E7 disrupts the function of Rb.

Recent phase 3 trials of HPV vaccines have shown promising results in the prevention of HPV subtype 16, 18, 31 and 33 infections and development of precancerous lesions. In the UK, the HPV vaccine programme commenced in September 2008 and offers Cervarix vaccine (GlaxoSmithKline, Bradford, UK) to all girls aged 12–13 years [5].

Müllerian duct anomalies are rare. The true prevalence is unknown but they are estimated to occur in 0.1–0.5% of women. Individuals with Müllerian duct anomalies commonly present with infertility [5]. Other related morbidities include primary amenorrhoea, retrograde menses, endometriosis, haematocolpos, and haematosalpinx. However, the presence of Müllerian duct anomalies are not associated with increased mortality or development of gynaecological cancers. Congenital renal anomalies are noted in some cases of Müllerian duct anomalies.

Development of the female urogenital tract in utero begins around the sixth week of embryological life. Three main structures are involved: genital ridge, mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts and paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts. Paramesonephric ducts are formed by invagination of coelomic epithelium lateral to the mesonephric ducts. They grow caudally, initially solid but later canalise. Distally the two mesospheric ducts fuse and the septum between the two ducts disappears to create the uterine cavity. Proximally mesonephric ducts canalise and form the fallopian tubes.

Congenital anatomical anomalies of Müllerian ducts are most commonly categorised according to the American Fertility Society (AFS) Scheme (1988) [6] as follows:

Class I : Hypoplasia/agenesis includes uterine and/or cervical agenesis or hypoplasia.

Class II : Unicornuate uterus is caused by arrest of development of one Müllerian duct. There may be a rudimentary horn with or without uterine cavity.

Class III : Didelphy uterus results from complete non-union of both Müllerian ducts. There are two uterine cavities and cervices. This anomaly is commonly associated with transverse vaginal septa.

Class IV : Bicornuate uterus is caused by partial non-union of Müllerian ducts at the level of fundus with resultant myometrium septum extending to the internal os (bicornuate unicollis) or external os (bicornuate bicollis).

Class V : Septate uterus results from failure of resorption of the septum between two Müllerian ducts.

Class VI : Arcuate uterus is a uterus with a single uterine cavity and convex or flat fundus.

Class VII : Disethylstilbestrol-related anomaly.

In our literature search, we only found one previous reported case of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix in didelphy uterus treated with radical radiation [7]. As such a condition is rarely seen, there is no standard radical radiation treatment plan that can readily applied. Owing to the anatomical anomaly, brachytherapy treatment can be challenging.

There have been reports published on cases of the coexistence of uterocervical abnormalities and carcinoma [8–16]. Nicholson et al [16] in 1961 reviewed this association in 87 patients. Three of the patients in the review had uterine didelphys and cervical carcinoma. At least three other cases of uterine didelphys and associated cervical carcinoma had been reported elsewhere [7, 8]. There is so far no evidence to suggest a link between congenital malformation of the female genital tract and the development of neoplasia.

There is only one publication describing brachytherapy as treatment of FIGO stage 2A squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with uterine didelphys [7]. Lee et al [7] described radical radiotherapy treatment using external photon beam therapy with a dose of 45 Gy in 25 fractions, followed by intracavity brachytherapy using a Microselectron high dose rate afterloading unit. Instead of using the traditional point A, which is localised 2 cm superior to the external cervical os and 2 cm lateral to the midline pelvis, the prescription point was 2 cm superior to the mean position of the small metallic flange located at each os cervix, at midline between the two intra-uterine tubes. The article by Lee et al [7] explained that changing the prescription point had the potential advantage of minimising the total dose at the midline tissue while maintaining adequate dose coverage to target tissue.

As we did not have a symmetrical dual-channel applicator as described by Lee et al, our approach has been to track the positions of the traditional A points so that within the possibilities of the asymmetric patient geometry our standard distribution was closely followed. After completion of brachytherapy, the brachytherapy doses to the A points were 18.0 Gy and 17.1 Gy. The pelvic lymph nodes received 4.6 Gy and 4.3 Gy and the vaginal wall received 26.8 Gy. The total reference air kerma rate was 0.0140 Gy at 1 m compared with 0.0155 Gy at 1 m for our standard treatment with this size applicator.

References

- 1.Dean EM, Lambert GD, Dawes PJDK. Gynaecological treatments using the Selectron remote afterloading system. Br J Radiol 1988;61:1053–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office forNationalStatistics. Cancer statistics registrations: registrations of cancer diagnosed in 2005, England. Series MB1 no.36. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004;324:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiley DJ, Douglas J, Beutner K, Cox T, Fife K, Moscicki AB, et al. External genital warts: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:5210–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department ofHealth HPV vaccine recommended for NHS immunisation programme. London: DH, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.The AmericanFertilitySociety The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligations, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies, and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril 1988;49:944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CD, Churn M, Haddad N, Davies-Humphries J, Kingston K, Jones B. Case report: Bilateral radical radiotherapy in a patient with uterus didelphys. Br J Radiol 2000;73:553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbett PJ, Crompton AC. Invasive carcinoma of one cervix in a uterus didelphys. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1982;89:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox S, Mones JM, Kronstadt R, et al. Bilateral and synchronous squamous cell carcinoma of cervix in a patient with uterine didelphys. Obstet Gynecol 1986;67:76s–79s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anneberg AD. Double vagina with double uterus (didelphys) containing endometrial adenocarcinoma. J Iowa Med Soc 1971;61:674–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun RD. Uterus didelphys and endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1970;35:93–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David SD, Nisbet JD. Uterine didelphys with adenoacanthoma involving one cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1972;112:1134–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David NP, Persitz E. Adenocarcinoma in a uterine duplex. Int Surg 1974;59:430–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fly OA, Pratt JH, Decker DG. Recurrence carcinoma of the cervix in patient having double cervix, uterus, and vagina. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1955;30:391–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant KB, Sedlacek RL. Uterus didelphys with adenocarcinoma in one fundus; a case report. J Iowa Med Soc 1970;60:324–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson R, Inza R, DiPaola G. Asociacion de malformacion y carcinoma uterino. La Prensa Med 1961;48:223 [Google Scholar]