Abstract

The fat-forming variant of solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) was previously called lipomatous haemangiopericytoma and is a rare variant of solitary fibrous tumour. It predominantly occurs in the deep soft tissues of the retroperitoneum and thigh. Only a handful of cases involving the perineum, spine, thoracic wall and pelvic cavity have been reported in the radiological literature and the fat-forming variant of SFT involving the pleura has not been previously reported. Herein, we report the CT findings of a case of the fat-forming variant of SFT involving the pleura that was treated by excision. Chest CT showed a large lobulated heterogeneous fatty mass with a multifocal enhancing soft-tissue component in the left lower hemithorax. Although rare, the fat-forming variant of SFT of the pleura should be added to the differential diagnosis of fat-containing pleural soft-tissue tumours.

The fat-forming variant of solitary fibrous tumour (SFT) is a recently recognised rare soft-tissue tumour. The fat-forming variant of SFT has a wide intra- and extrathoracic anatomical distribution but the deep soft tissues of the retroperitoneum and thigh are the most commonly affected sites [1]. The fat-forming variant of SFT involving the thoracic cavity is very rare with only five reported cases involving the mediastinum [2-4], epicardium [2] and lung [5]. These reports focused on characterising the clinicopathological features. To the best of our knowledge, the radiological features of this tumour have not been well described. Therefore, we report the CT findings of a 74-year-old man with a fat-forming variant of SFT involving the pleura that was treated by excision.

Case report

A 74-year-old man was admitted with aggravated dyspnoea that had developed over the previous year. No abnormalities were noted on the physical examination or routine laboratory studies.

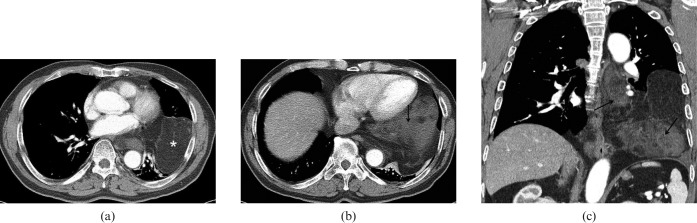

The posteroanterior chest radiograph showed a large left lower hemithoracic mass that was abutted against the diaphragm. Contrast-enhanced chest CT (Sensation 16; Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) showed a large heterogeneous predominant fatty mass (Figure 1a) that was attached posteroinferiorly to the mediastinum, pleura and diaphragm. Adjacent structures such as the oesophagus, pulmonary vessels and bronchi were compressed and displaced but not clearly infiltrated. The mass was well circumscribed and lobulated (12×13×13 cm) and was largely composed of fat and a significantly sized, well-enhancing soft-tissue component (Figure 1b, c). It was difficult to determine the origin of the mass, but we thought that it was of pleural rather than mediastinal origin because the mass was extensively attached to the diaphragm and pleura. The initial clinicoradiological diagnosis was liposarcoma that originated from the pleura.

Figure 1.

(a) Contrast-enhanced chest CT axial image shows a well-defined, lobulated heterogeneous mass with predominant fat attenuation (asterisk). (b) Contrast-enhanced chest CT axial image caudal to (a) shows multiple soft-tissue components with enhancement (arrow) in the lower part of the tumour. (c) Coronal reconstruction image shows a large fatty mass occupying most of the left lower hemithorax. The lower and medial part of the tumour appears solid with enhancement (arrow).

We performed a CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy to make an initial diagnosis because we had no experience with large predominant fatty liposarcomas of the pleura and could not completely rule out the presence of another rare benign fatty pleural tumour. Microscopically, the tumour was a mesenchymal neoplasm with spindle cells, a mature fat component and collagenous stroma. Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for CD34 and CD99, as is typical for SFT, whereas the S-100 and smooth muscle actin were negative.

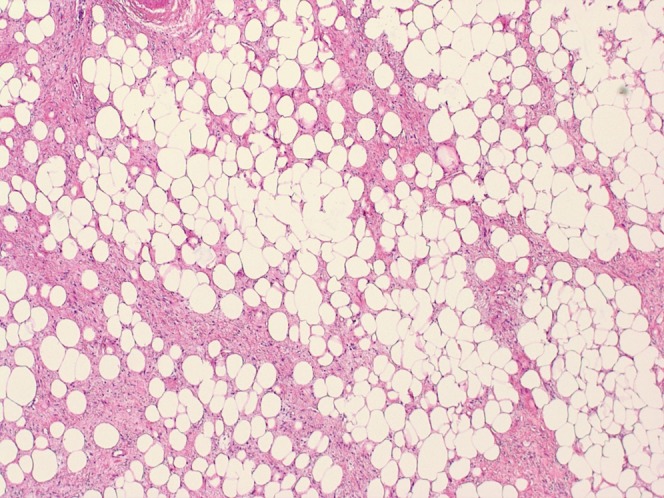

Surgical excision of the mass was subsequently performed. At surgery, the tumour was found to originate from the pleura. The gross specimen consisted of fragments of solid soft masses and membranous soft tissue. Microscopically, the mass consisted of mature adipose tissue and fibrovascular tissue without mitosis or necrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemically, the tumour cells were positive for CD34, Bcl-2 and vimentin, but negative for S-100 and smooth muscle actin. These features are characteristic of the fat-forming variant of SFT.

Figure 2.

Histopathological examination (haematoxylin and eosin stain, ×40) of the mass reveals that the tumour is composed of haemangiopericytoma-like areas admixed with areas of mature adipocytes.

Post-operatively, the patient's dyspnoea improved and he did not undergo additional therapies such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The post-operative 5 month follow-up CT (Figure 3) revealed a residual tumour at the pre-aortic recess. After the follow-up chest CT, the patient had regular follow-up with chest radiographs. There was no evidence of further growth of the residual tumour or metastasis 14 months after surgery.

Figure 3.

Follow-up contrast-enhanced chest CT axial image shows a residual tumour at the pre-aortic recess.

Discussion

SFTs have been subclassified into the newly proposed SFT designation [1] as the fibrous form, the cellular form, the fat-forming variant and giant cell-rich variant of SFT. The fibrous form of SFT, the more common form, is characterised by the alternating presence of cellular and fibrous areas. The cellular form of SFT characteristically contains moderate to high cellularity and not much intervening fibrosis. In addition to the fibrotic and cellular forms of SFT, several other unusual variants may contain mature adipocytes and/or giant multinucleated stromal cells: these are the so-called fat-forming variant and the giant cell-rich variant of SFT.

The fat-forming variant of SFT is a recently recognised rare variant of SFT and it is composed of haemangiopericytoma-like areas interspersed with mature adipose tissue [1,2]. This tumour was originally designated as “ipomatous haemangiopericytoma” by Nielsen et al [6]. Subsequently, several reports in the literature [1,2,7] noted that lipomatous haemangiopericytoma and SFT share similar clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, except for the presence of mature adipocytes. The authors of these reports suggested that lipomatous haemangiopericytoma is likely to represent a fat-containing variant of SFT.

To the best of our knowledge, only 50 such cases have been reported in the English medical literature [2-15]. The fat-forming variant of SFT has shown a wide anatomical distribution, but the commonly affected sites are the lower extremities and retroperitoneum. The thoracic cavity was an unusual location and this included the mediastinum [2-4] in three cases, the epicardium [2] in one case and the lung [5] in one case. There are no previous reports of a fat-forming variant of SFT arising from the pleura. To date, there have been only eight case reports describing the CT or MRI findings of the fat-forming variant of SFT and these cases involved the perineum [8], spine [9], kidney [10], orbit [11], skull base [12], neck [13], thoracic wall [14] and pelvic cavity [14]. In these reports, except for one case involving the spine in which the post-contrast images were not obtained, all the tumours showed similar radiological findings of a well defined and enhanced hypervascular mass. In only five (perineum, spine, skull base, thoracic wall and pelvic cavity) of these cases was a small amount of intratumoural fat found on the CT or MRI. However, in our case in which the tumour arose from the pleura, we detected a large area of fatty component within the tumour, which may have led to a broader differential diagnosis that included soft-tissue tumours containing a lipomatous component, such as liposarcoma and atypical lipomatous tumour. In fact, the initial clinicoradiological diagnosis in our case was well-differentiated liposarcoma that originated from the pleura.

Grossly, the fat-forming variant of SFT generally presents as a well-demarcated, variably encapsulated, medium-sized, mesenchymal tumour [2]. Histologically, most tumours in the reported cases resemble the cellular form of SFT except for the added presence of a variable number of mature, non-atypical adiopocytes [1].

The fat-forming variant of SFT usually occurs in middle-aged adults and most lesions are clinically detected as a longstanding indolent tumour that does not metastasise or recur after resection [1]. In our case, post-operative 5 month follow-up contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed a residual tumour at the pre-aortic recess. The patient did not undergo additional surgery of the residual tumour and had regular follow-ups with chest radiographs. There was no evidence of further growth or metastasis 14 months after surgery.

In conclusion, we report for the first time the CT findings of a fat-forming variant of SFT involving the pleura. The tumour was large, more than 12 cm in diameter and had a predominant fatty component, leading to an initial diagnosis of liposarcoma. Although rare, the fat-forming variant of SFT of the pleura should be considered in the differential diagnosis of fat-containing pleural soft-tissue tumours.

References

- 1.Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology 2006;48:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillou L, Gebhard S, Coindre JM. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor? Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analysis of a series in favor of a unifying concept. Hum Pathol 2000;31:1108–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amonkar GP, Deshpande JR, Kandalkar BM. An unusual lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. J Postgrad Med 2006;52:71–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Zhang HY, Bu H, Meng GZ, Zhang Z, Ke Q. Fat-forming variant of solitary fibrous tumor of the mediastinum. Chin Med J 2007;120:1029–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki K, Eyden BP. Pulmonary lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: report of a rare tumor and comparison with solitary fibrous tumour. Ultrastruct Pathol 2007;31:51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen GP, Dickersin GR, Provenzal JM, Rosenberg AE. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. A histologic, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a unique variant of hemangiopericytoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:748–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folpe AL, Devaney K, Weiss SW. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a rare variant of hemangiopericytoma that may be confused with liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MY, Rha SE, Oh SN, Lee YJ, Byun JY, Jung CK, et al. Case report. Lipomatous haemangiopericytoma (fat-forming solitary fibrous tumour) involving the perineum: CT and MRI findings and pathological correlation. Br J Radiol 2009;82:e23–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aftab S, Casey A, Tirabosco R, Kabir SR, Saifuddin A. Fat-forming solitary fibrous tumour (lipomatous haemangiopericytoma) of the spine: case report and literature review. Skeletal Radiol 2010;39:1039–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi T, Takimoto T, Yamashita T, Kitahara S, Omura M, Ueda Y. Fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor (lipomatous hemangiopericytoma) arising on surface of kidney. Urology 2005;65:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies PE, Davis GJ, Dodd T, Selva D. Orbital lipomatous haemangiopericytoma: an unusual variant. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2002;30:281–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaia WT, Bojrab DI, Babu S, Pieper DR. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the skull base and parapharyngeal space. Otol Neurotol 2006;27:560–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alrawi SJ, Deeb G, Cheney R, Wallace P, Loree T, Rigual N, et al. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma of the head and neck: immunohistochemical and DNA ploidy analyses. Head Neck 2004;26:544–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wignall OJ, Moskovic EC, Thway K, Thomas JM. Solitary fibrous tumors of the soft tissues: review of the imaging and clinical features with histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:W55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dozois EJ, Malireddy KK, Bower TC, Stanson AW, Sim FH. Management of a retrorectal lipomatous hemangiopericytoma by preoperative vascular embolization and a multidisciplinary surgical team: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1017–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]