Abstract

The “spot sign”, first described in 2007, has shown that a focal area of contrast extravasation within an intracerebral haematoma (ICH) can be correlated with haematoma expansion. We describe a case where time-resolved dynamic CT angiography (dCTA) shows the appearance of the “spot sign” only in later images. This finding highlights the importance of timing of the static CT angiogram which, if performed too early, might result in a false-negative diagnosis.

Contrast extravasation into an intracerebral haemorrhage has been associated with haematoma growth and poor clinical outcomes including death [1, 2]. More recently, the “spot sign” has been validated as a marker of intracerebral haematoma (ICH) expansion [3]. However, these imaging studies are static, acquired at a particular point in time. Dynamic CT angiography (dCTA) demonstrates temporal wash-in and wash-out of intravenous contrast material over a chosen temporal resolution. This allows temporal visualisation of contrast flowing through vessels. We present a case capturing distinct areas of “spot sign” within an acute ICH using time-resolved dCTA.

The success of future therapies, including haemostatic agents, for the treatment of ICH may depend on accurate determination of haematomas at risk of expansion [4].

Case

An 86-year-old woman presented to the emergency room 2 h after developing acute left-sided hemiparesis. The admission unenhanced CT scan showed a 25 cm3 intraparenchymal haematoma centred in the left lentiform nucleus with mild midline shift (Figure 1a). Her medical history was remarkable for atrial fibrillation and Alzheimer's dementia. Relevant medications included warfarin and donepezil. Her international normalised ratio (INR) on presentation was 2.1; this was quickly reversed to 1.3 using prothrombin complex concentrate.

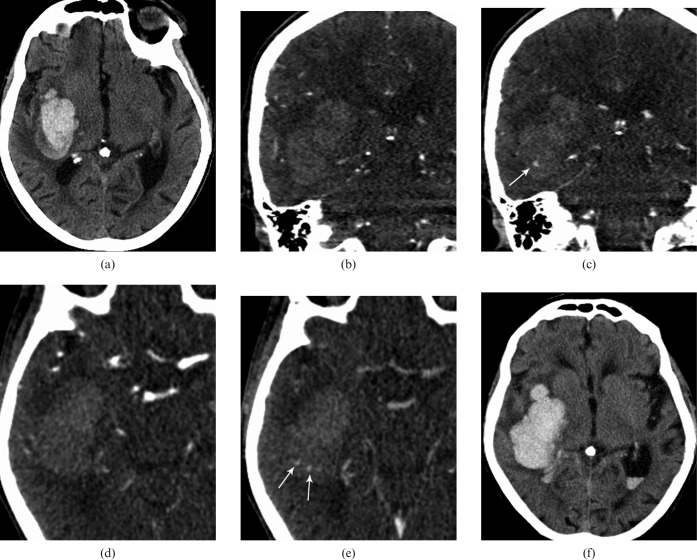

Figure 1.

Axial non-contrast CT on admission (a) showed a large parenchymal haematoma in the right frontotemporal lobe. (b–d) Coronal reformats of dynamic CT angiography (dCTA) in arterial and late venous phase (44 s) showed development of an area of “spot sign” (arrow in c). (e) Axial dCTA images in arterial (d) and late venous phase (49 s) shows development of another two areas of contrast extravasation (arrows). An axial CT image on day 2 (f) shows expansion of the haematoma with intraventricular haemorrhage.

12 h after admission, her clinical status deteriorated necessitating intubation for airway protection. Repeat CT scan confirmed haematoma expansion to 41 cm3 with significant bilateral intraventricular extension (Figure 1f). The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, but her condition failed to improve. After 48 h, withdrawal of care was discussed with her family and she died shortly afterwards.

Image acquisition

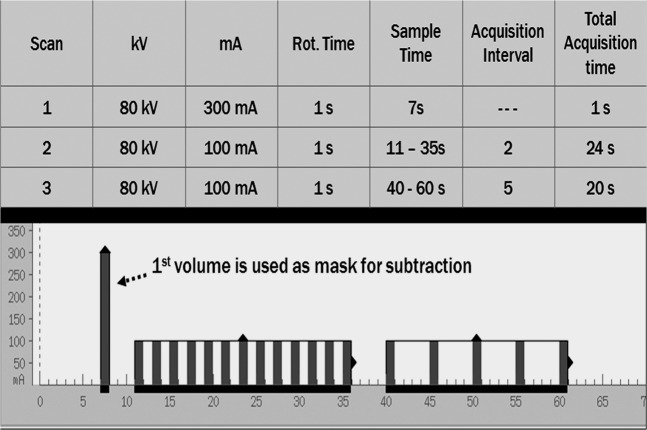

Admission non-contrast CT was performed in a 64-slice GE scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Owing to the history of dementia and acute cognitive limitations resulting from the ICH, consent was obtained from two relatives as per the approved ethics protocol (PREDICT study) at our institution. The patient was brought for a dynamic CT angiogram in a 320-row volume CT scanner (Aquilion ONETM Toshiba, Japan). This system utilises 320 ultra-high-resolution detector rows (0.5 mm in width) to image the entire brain in a single gantry rotation. dCTA is a non-invasive technique to acquire a time series of bone subtracted or unsubtracted CT angiogram images of the whole brain, thus removing timing uncertainties found in typical static CT angiogram images. This approach also provides temporal flow information. Presently, there is a limitation of computational power with 23 volumes of data that can be processed at one time. The single volume acquisition takes 1 s, resulting in a temporal resolution of 1 s−1. By manipulating the raw data improved temporal resolution up to 5 s−1 is possible. The data acquisition protocol is described in Figure 2. The dose–length product (DLP) reading for this study was 1925 mGy-cm compared with a helical CT head scan, which has a value of 1349 mGy-cm.

Figure 2.

Detailed scan parameters for the dynamic CT angiography acquisition are shown. In the lower panel, the timing of the acquisition volumes are shown with the x-axis representing time in seconds.

Imaging analysis

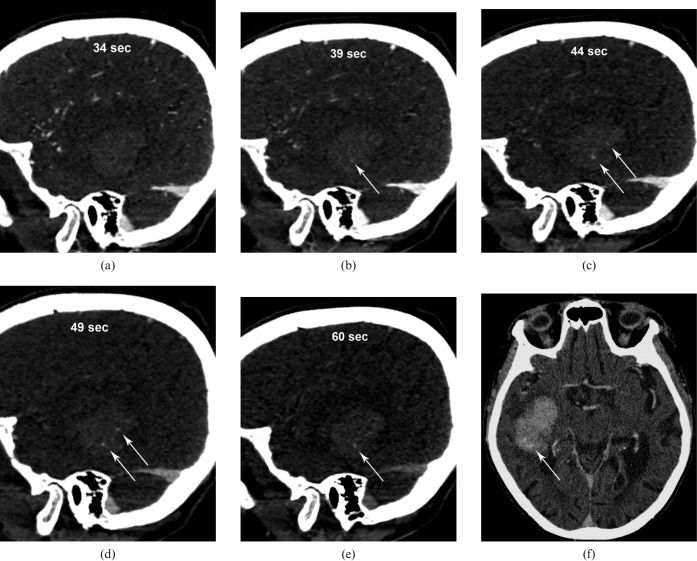

On the dCTA images (Figure 1b–e, Figure 3a–e), initial arterial filling is seen 21 s after the beginning of the contrast injection followed by filling of the sagittal sinus at 28 s. Initial images through the area of haemorrhage did not reveal any evidence of contrast extravasation (Figure 3a). At 39 s, a single area of extravasation appeared in the lower aspect of the haematoma (Figure 3b,c). After 44 s, two other areas of contrast extravasation were seen in the superior portion of the haematoma (Figures 1e and 3c). At 60 s, the superior areas of contrast faded, although the more inferior extravasation persisted. The dynamic sequence is shown in Figure 3a–e in oblique sagittal sections at 34 s, 39 s, 44 s, 49 s and 60 s. Post-contrast brain immediately following the dCTA (Figure 3f) at the level of superior “spot sign” was shown. This is likely to be related to the dispersion of the contrast agent in the adjacent haematoma.

Figure 3.

Oblique sagittal sections of the dynamic CT angiography (dCTA) sequence show the evolution of “spot signs” at (a) 34 s, (b) 39 s, (c) 44 s, (d) 49 s and (e) 60 s. (f) Post-contrast brain immediately following dCTA at the level of superior “spot sign” shows fading of the superior “spots”.

Discussion

ICH growth occurs early after onset and has been shown to be an independent marker for poor clinical outcome [1, 2, 5]. The “spot sign” is thought to represent contrast pooling within or around a haematoma and can predict future haematoma growth [6]. The primary source of haemorrhage resulting in the “spot sign” is unknown; however, possibilities include microaneurysms and fibrin globes, such as proposed by Fisher [7]. The radiological findings of early “spot signs” and later contrast extravasation also bring into question whether there may exist a primary source of haemorrhage followed by secondary sources. Determining the dynamic nature of these findings might assist in understanding the underlying pathophysiology.

The optimal CT operating parameters for detection of contrast extravasation and visualisation of the “spot sign” are not known. Our findings may explain why early descriptions of the “spot sign” did not demonstrate a robust predictive value. A more recent article suggests that inclusion of both the “spot sign” and a second static delayed scan for contrast extravasation will improve the sensitivity for detection of ICH expansion to 0.94 and the negative predictive value to 0.97 [8]. An understanding of the dynamic nature of these findings through dCTA may further assist in refining these parameters.

The multiple data sets obtained at progressive time intervals in our case were beneficial in demonstrating active contrast extravasation, which was not initially seen on the earlier images. In one portion of the haematoma the contrast extravasation was evident later on in the dynamic sequence, then faded. In another portion, the extravasation arrived later, then persisted. This observation illustrates the dynamic nature of some ICHs and the potential limitation of static CTA imaging in capturing some “spot signs”.

Our case involves warfarin-associated ICH. We are uncertain if the findings would be seen in other causes of ICH such as hypertension or amyloid angiopathy.

Conclusion

We report a case involving time-resolved dCTA imaging that demonstrated active contrast extravasation and evolution of the “spot sign” in an ICH. This case illustrates that the “spot sign” may be an intermittent finding and might temporally evolve. Evaluating ICH with dCTA could lead to a better understanding of haematoma evolution.

References

- 1.Kim J, Smith A, Hemphill JC, 3rd, Smith WS, Lu Y, Dillon WP, et al. Contrast extravasation on CT predicts mortality in primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:520–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Abouelsaad T, Cohen WA. Extravasation of radiographic contrast is an independent predictor of death in primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1999;30:2025–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demchuck AM, Subramaniam S, Kosior J, Tymchuk S, O'Reilly C, Molina C, et al. Multicentre prospective study demonstrates feasibility of CT-angiography in intracerebral hemorrhage and validity of “spot sign” for hematoma expansion prediction. Abstract Stroke 2008;39:527 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer S, Brun NC, Begtrup K, Broderick J, Davis S, Diringer MN, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2127–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, et al. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1997;28:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wada R, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Sahlas DJ, Gladstone DJ, Tomlinson G, et al. CT angiography “spot sign” predicts hematoma expansion in acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2007;38:1257–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher CM. Pathological observations in hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1971;30:536–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ederies A, Demchuck A, Chia T, Gladstone DJ, Dowlatshahi D, BenDavit G, et al. Postcontrast CT extravasation is associated with hematoma expansion in CTA spot negative patients. Stroke 2009;40:1672–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]