Abstract

Objective

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scans can improve target definition in radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). As staging PET/CT scans are increasingly available, we evaluated different methods for co-registration of staging PET/CT data to radiotherapy simulation (RTP) scans.

Methods

10 patients underwent staging PET/CT followed by RTP PET/CT. On both scans, gross tumour volumes (GTVs) were delineated using CT (GTVCT) and PET display settings. Four PET-based contours (manual delineation, two threshold methods and a source-to-background ratio method) were delineated. The CT component of the staging scan was co-registered using both rigid and deformable techniques to the CT component of RTP PET/CT. Subsequently rigid registration and deformation warps were used to transfer PET and CT contours from the staging scan to the RTP scan. Dice's similarity coefficient (DSC) was used to assess the registration accuracy of staging-based GTVs following both registration methods with the GTVs delineated on the RTP PET/CT scan.

Results

When the GTVCT delineated on the staging scan after both rigid registration and deformation was compared with the GTVCTon the RTP scan, a significant improvement in overlap (registration) using deformation was observed (mean DSC 0.66 for rigid registration and 0.82 for deformable registration, p = 0.008). A similar comparison for PET contours revealed no significant improvement in overlap with the use of deformable registration.

Conclusions

No consistent improvements in similarity measures were observed when deformable registration was used for transferring PET-based contours from a staging PET/CT. This suggests that currently the use of rigid registration remains the most appropriate method for RTP in NSCLC.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scanning is now a standard procedure for staging patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1]. PET/CT imaging is also beneficial in radiotherapy treatment planning (RTP), for example by identifying metastases to mediastinal lymph nodes. PET/CT for RTP simulation has also been shown to reduce interobserver variation in gross tumour volume (GTV) delineation [2,3].

Metabolic information can be incorporated into the RTP process by performing a dedicated RTP PET/CT simulation with the patient positioned in the treatment position and on a flat couch top [4,5]. This approach is superior to using CT alone for simulation, followed by visual correlation with PET [3]. However, acquiring a second PET/CT scan involves extra costs as well as increasing the radiation dose to the patient and the staff involved in the scanning procedure owing to the administration of a second dose of radiopharmaceutical [6]. As staging PET/CT scans are increasingly available in patients who are referred for radiotherapy, other investigators have described methods of co-registering staging PET/CT and RTP CT simulation scans [7]. However, diagnostic scanning protocols are usually acquired on a curved couch top, and differences in anatomical positioning may hinder accurate co-registration. Positioning a patient in the radiotherapy treatment position during the staging PET scan acquisition, by use of a flat table insert, improves the accuracy of rigid registration of staging and RTP CT scan [8].

Deformable registration seeks to reduce potential differences between imaging data sets, such as differences in anatomical positioning, by estimating the spatial relationship between volume elements of the scan sets, while maintaining the modality-specific information [9]. The correct estimation of these differences may permit the accurate transfer of radiotherapy target volume structures between image data sets. The use of deformable registration has been shown to allow for more accurate registration of a staging PET/CT scan to a RTP CT scan in patients with head and neck tumours [10,11]. However, caution has been advised as the benefits of using deformable registration for this purpose for thoracic tumours is unproven [12]. In the present study, we assess the accuracy of both rigid and deformable registration for transferring target volumes delineated on a staging PET/CT scan to a RTP scan in NSCLC.

Methods

Patient selection

Between November 2004 and June 2007, a study, approved by the ethics committee, at the Northern Ireland Cancer Centre, Belfast, enrolled patients with pathologically proven, inoperable NSCLC, Stages I–IIIB (American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging) [13]. Eligible patients had a prior staging 18F-FDG PET/CT scan [3]. Included in this investigation were patients treated with radiation alone and having a maximum time of 9 weeks between staging and RTP PET/CT scans.

Staging PET/CT scan acquisition

Both staging and RTP PET/CT scans were acquired using the same General Electric Discovery Lightspeed Combined PET/CT scanner (GE Medical System, Milwaukee, WI). For the staging scans, patients were positioned on the standard diagnostic curved couch top, with arms raised above the patient's head. An intravenous injection of 18F-FDG (375 MBq) was followed by a minimum 45 min uptake period. Transmission CT scanning followed by emission PET scanning was undertaken from above the vertex of the skull to the mid-thigh level. A standard diagnostic imaging protocol was used and no special breathing instructions were given during the CT acquisition. In keeping with the institutional protocol, no intravenous contrast was used during CT acquisition.

RTP PET/CT scan acquisition

The RTP PET/CT scan was performed with the patients immobilised using a locally modified Med-TEC thorax immobilisation board (Med-TEC, Orange City, IA) and a knee rest [14]. The immobilisation board was positioned on a flat-top couch insert. After an intravenous injection of 18F-FDG (375 MBq), followed by a 45 min uptake period, patients were scanned in the treatment position with both arms raised above their head. A standard diagnostic imaging protocol identical to that used in the staging scan acquisition was used and no special breathing instructions were given during the CT acquisition. No intravenous contrast was used during CT acquisition and image acquisition was confined to the thorax. To confirm that there was no significant misregistration or patient movement between the CT and PET components of the scan, visual inspection of the image data set after scanning was performed by the technologists acquiring the images.

Target volume delineation

On both the staging and RTP PET/CT scans, target volumes were delineated using Velocity AI (Velocity Medical Solutions, Version 2.1.1, Atlanta, GA). Delineation was undertaken by a single radiation oncologist with a special interest in lung cancer. Using the CT images alone the GTV of the primary tumour alone (GTVCT) was delineated using standardised lung (Width (W) = 100, Centre (C) = −700) and mediastinal window (W = 350, C = 40) settings. Given that no single optimal method of PET-based target volume delineation in lung cancer exists, four different methods of PET-based target volume PET delineation were used [15]. The four PET-based contour delineation methods included:

A manual PET contour (GTVPETMAN) was generated following delineation using a standardised window setting, with the window width equal to the maximum of the pixel intensity within the target image and the window level equal to half this maximum [3].

Two absolute threshold PET contours were delineated using an absolute standardised uptake value (SUV) threshold of 2.5 (GTVSUV2.5) and a threshold of 35% (GTV35%SUVMAX) of the maximal SUV within the target image (SUVMAX) [16,17].

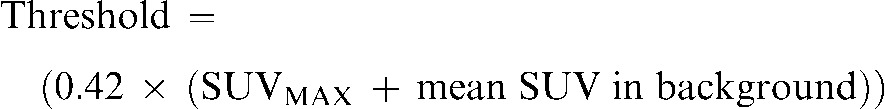

- A fourth PET contour (GTVPETSBR) used a modification of the source-to-background algorithm as described by Boellaard et al [18]. In the first instance, a region of interest (ROI) around the tumour volume was defined and the SUVMAX within this ROI was measured. Then the mean SUV of the background activity in tissue surrounding the tumour was measured. Finally, the threshold defining the GTVPETSBR is given by the following equation:

(1)

Rigid and deformable registration of staging PET/CT scan to RTP PET/CT scan

As both scans were obtained using an inline PET/CT scanner, the PET and CT scan components automatically share Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) coordinates. Thus, additional co-registration is not needed as patients are not repositioned during these scan acquisitions and no major misalignment was detected. Given the low resolution of the PET images and the lack of clear discernable normal landmarks, all registration was undertaken using the CT components of the staging and planning PET/CT scans. Registration of the PET scans was therefore performed using the same registration parameters of the CT to CT-based registration. For CT–CT registration, initially, a rigid registration focusing on the dorsal spine was undertaken using the Velocity AI application.

Following rigid registration, image deformation, using Velocity AI, was then performed. In this process the CT components of the PET/CT scans were deformed to the CT of the planning scan using a modified basis spline (B-spline) registration algorithm combined with the Mattes [19] formulation of the mutual information metric. Deformable registration is an optimisation process that aims to recover the unknown parameters of any transformation that is required to correlate matching anatomic features observed in two different scan images of the same patient. An interactive iterative process is used to modify the transformation parameters until an optimal match is found between the scan images. In the current study deformable registration was performed using default software settings using a coarse grid with a maximum deformation distance of 50 mm. A three-step deformation was employed with the initial deformable registration that involved the entire lung volume, followed by two additional deformable registrations restricted to the tumour-bearing region, including a sufficient amount of surrounding lung tissue and sometimes including adjacent chest wall or vertebra, depending on the location of the tumour. In a recent comparison of deformation techniques, the B-spline local deformation technique used in this investigation had the smallest error of the various deformation methods investigated [20].

Transfer of target volumes using rigid and deformable registration

The GTVCT, GTVPETMAN,GTVSUV2.5, GTV35%SUVMAX and the GTVPETSBR contours delineated on the staging PET/CT scan set were transferred to the RTP PET/CT scan set using:

a linear transformation with the same displacements and rotations used in the rigid registration process between the CT data sets;

the ”warp„ arrived at in the deformation process and using the same three-dimensional (3D) displacement vectors between the CT data sets.

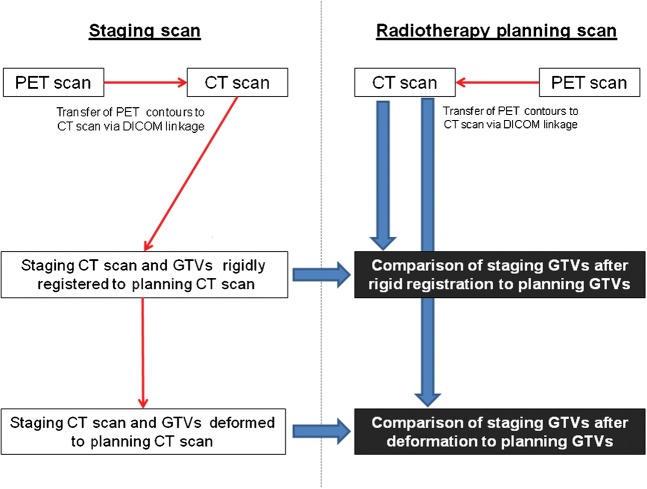

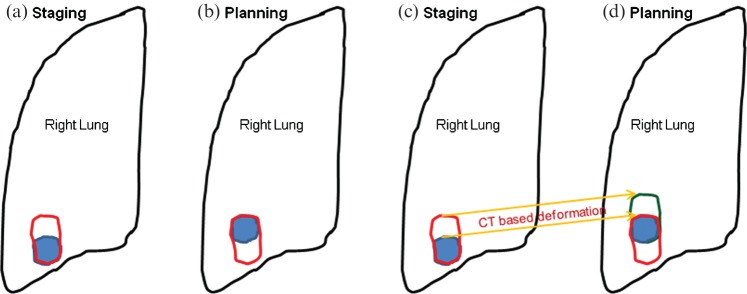

A schema of the registration steps and transfer of contours is illustrated in Figure 1 and the nomenclature of the GTVCT and the four PET-based GTV contours is detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schema of registration of the CT component of the staging positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan to radiotherapy planning PET/CT scan, transfer of gross tumour volume (GTV) contours and comparison of delineated volumes.

Table 1. Gross tumour volume (GTV) contour nomenclature at each step of registration.

| Staging PET/CT scan outlines | Staging PET/CT scan outlines after rigid registration to RTP PET/CT scan | Staging PET/CT scan outlines after deformable registration to RTP PET/CT scan | RTP PET/CT scan outlines |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GTV, gross tumour volume; PET, positron emission tomography; RTP, radiotherapy treatment planning; SUV, standardised update value.

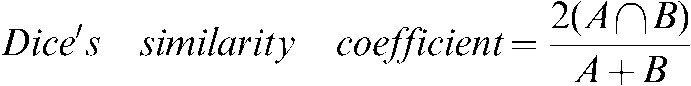

Comparison of volumes and statistical analysis

The target volumes from the staging PET/CT scan transferred using rigid registration and using deformable registration were compared with the same contours on the RTP PET/CT scan. The percentage volume change (PVC) in the GTV from the staging scan at the different steps of registration with the same GTV type on the RTP scan was calculated. To assess positional change the 3D vector distance between the centre of mass (COM) of the GTV before and after each registration step and the GTV on the RTP scan was derived. Dice's similarity coefficient (DSC), assessing volumetric shape and positional change in a single measure, was calculated between the staging GTVs during and after the registration steps and the same GTV on the RTP scan. DSC, for the ratio of overlap between volumes A and B, is given by [21,22]:

|

(2) |

Descriptive statistics and paired t-tests (two-tailed) were used to examine any differences between data pairs and significance was reached for p-values being <0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the 10 patients included in this analysis are listed in Table 2. In all PET/CT scans reviewed, visual inspection revealed no major misalignment between the CT and PET components. The GTVs on staging and RTP PET/CT scans and at both steps of image registration are listed in Table 3. Patients 3, 8 and 10 had an increase of 25% or more in the GTVCT between staging and RTP scans. Of note, Patients 3 and 8 had distal atelectasis. Results obtained for the COM and DSC analysis for all patients are listed in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 2. Baseline tumour characteristics.

| Patient no. | Stage | Side | Lobe | Position | Pathology | Staging PET/CT SUVMAX | RTP PET/CT SUVMAX |

| 1 | IB | Right | Middle | Peripheral | NSCLC | 11.4 | 11.6 |

| 2 | IB | Left | Lower | Central | Squamous | 12.9 | 10.3 |

| 3 | IIIB | Right | Upper | Central | Squamous | 11.6 | 11.8 |

| 4 | IIIA | Right | Lower | Peripheral | Squamous | 15.6 | 15.1 |

| 5 | IA | Left | Upper | Peripheral | Squamous | 10.8 | 10.3 |

| 6 | IIIB | Right | Upper | Central | Squamous | 11.1 | 10.0 |

| 7 | IA | Left | Lower | Peripheral | NSCLC | 6.7 | 8.1 |

| 8 | IIIB | Right | Upper | Peripheral | Squamous | 16.6 | 15.6 |

| 9 | IIB | Right | Upper | Peripheral | NSCLC | 12.2 | 12.2 |

| 10 | IB | Right | Upper | Peripheral | NSCLC | 6.4 | 7.2 |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PET, positron emission tomography; RTP, radiotherapy treatment planning; SUV, standardised uptake value.

Table 3. Measurements (ml) of the gross tumour volume (GTV) on the staging positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan, after rigid registration, after deformable registration and the GTV as delineated on the radiotherapy treatment planning (RTP) PET/CT scan.

| Patient | Delineation method | GTV on staging scan (ml) | GTV from staging scan after rigid registration (ml) | GTV from staging scan after deformable registration (ml) | GTV on RTP scan (ml) |

| 1 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 16.0 | 16.0 | 20.2 | 21.2 |

| GTVPETSBR | 12.4 | 12.4 | 15.7 | 16.3 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 22.0 | 22.0 | 28.8 | 31.5 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 23.3 | 23.3 | 30.5 | 31.1 | |

| GTVCT | 20.8 | 20.8 | 26.0 | 25.0 | |

| 2 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 16.1 | 16.2 | 12.7 | 19.4 |

| GTVPETSBR | 8.8 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 11.8 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 30.0 | 30.0 | 24.1 | 22.7 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 36.7 | 36.7 | 29.6 | 32.2 | |

| GTVCT | 46.4 | 46.4 | 36.0 | 20.8 | |

| 3 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 35.8 | 35.8 | 34.5 | 57.8 |

| GTVPETSBR | 26.3 | 26.3 | 25.9 | 37.9 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 48.8 | 48.8 | 50.4 | 59.9 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 53.6 | 53.6 | 54.4 | 103.8 | |

| GTVCT | 39.3 | 39.3 | 40.7 | 50.9 | |

| 4 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 107.1 | 107.1 | 101.3 | 106.5 |

| GTVPETSBR | 80.2 | 80.2 | 75.6 | 71.6 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 146.9 | 146.9 | 139.3 | 141.8 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 181.1 | 181.1 | 173.6 | 163.3 | |

| GTVCT | 101.3 | 101.3 | 95.0 | 98.9 | |

| 5 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 7.7 |

| GTVPETSBR | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.3 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 13.2 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 10.4 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 11.2 | |

| GTVCT | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 5.6 | |

| 6 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 10.9 | 10.9 | 9.2 | 11.9 |

| GTVPETSBR | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 6.7 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 13.2 | 13.2 | 11.1 | 9.2 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 22.1 | 22.1 | 19.9 | 21.8 | |

| GTVCT | 20.4 | 20.4 | 18.5 | 17.8 | |

| 7 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 14.0 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 10.0 |

| GTVPETSBR | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 5.8 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 11.6 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 11.2 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 12.0 | |

| GTVCT | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 4.5 | |

| 8 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 57.8 | 57.8 | 86.9 | 130 |

| GTVPETSBR | 46.2 | 46.2 | 66.0 | 46.1 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 73.9 | 73.9 | 107.9 | 64.3 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 99.1 | 99.1 | 138.4 | 120.4 | |

| GTVCT | 81.7 | 81.7 | 128.8 | 134.8 | |

| 9 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 22.9 | 22.9 | 24.0 | 27.0 |

| GTVPETSBR | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.6 | 14.9 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 33.2 | 33.2 | 34.9 | 37.3 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 40.4 | 45.4 | |

| GTVCT | 33.4 | 33.4 | 35.7 | 37.2 | |

| 10 | GTV35%SUVMAX | 8.3 | 8.3 | 16.0 | 18.8 |

| GTVPETSBR | 5.3 | 5.3 | 11.7 | 13.5 | |

| GTVPETMAN | 7.9 | 7.9 | 15.6 | 18.8 | |

| GTVSUV2.5 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 14.3 | 18.1 | |

| GTVCT | 6.3 | 6.3 | 13.2 | 15.4 |

Table 4. Displacement of centre of mass (mm) between the gross tumour volume (GTV) contours on the staging positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan when registered using both rigid and deformable approaches with the CT component of the simulation PET/CT scan when compared with contours obtained using the simulation PET/CT scan alone.

| Patient | Comparison | Vector size (mm) between centre of mass of GTV from staging scan after rigid registration or deformation to RTP scan and the centre of mass on the RTP scan |

||||

| GTV35%SUVMAX | GTVPETSBR | GTVPETMAN | GTVSUV2.5 | GTVCT | ||

| 1 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 9.3 | 13.7 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 3.6 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 10.0 | 8.4 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 2.2 | |

| 2 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 2.4 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 13.2 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 17.7 | 17.7 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 3.7 | |

| 3 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 13.8 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 15.2 | 4.6 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 12.1 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 13.0 | 3.6 | |

| 4 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 4.3 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 2.2 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 5.2 | 4.8 | 7.6 | 9.7 | 4.8 | |

| 5 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 1.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 2.3 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 2.5 | |

| 6 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 5.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 15.4 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 3.7 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 9.9 | |

| 7 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 6.1 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.4 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 3.9 | 7.7 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 1.5 | |

| 8 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 15.7 | 20.8 | 18.8 | 16.1 | 17.1 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 11.7 | 11.0 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 4.1 | |

| 9 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 4.9 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.7 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 5.2 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.2 | |

| 10 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 10.0 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 2.2 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 1.1 | |

Table 5. Dice's similarity coefficient measurements between contours on the staging positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan using both rigid and deformable co-registration to the CT component of the simulation PET/CT scan when compared with contours derived using only the simulation PET/CT scan alone.

| Patient | Comparison | Dice's similarity coefficient measurements between GTV from staging scan after rigid registration or deformation to the RTP scan and the GTV on the RTP scan |

||||

| GTV35%SUVMAX | GTVPETSBR | GTVPETMAN | GTVSUV2.5 | GTVCT | ||

| 1 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.86 | |

| 2 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.50 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.72 | |

| 3 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.82 | |

| 4 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.91 | |

| 5 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.76 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.82 | |

| 6 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.45 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.63 | |

| 7 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.55 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.79 | |

| 8 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.80 | |

| 9 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.90 | |

| 10 | Staging GTV after RIGID registration with RTP GTV | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Staging GTV after DEFORMATION with RTP GTV | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.86 | |

Comparing the differences between the staging GTVCT following rigid registration and deformable registration and the GTVCT on the RTP scan ( with the

with the  and the

and the  with the

with the  ) the

) the  had greater overall positional and volumetric similarity with the

had greater overall positional and volumetric similarity with the  In the comparison of GTVCT contours the use of deformable registration resulted in a greater reduction in the COM displacement in 8 of the 10 patients, and an improvement in DSC for 9 of the 10 patients compared with rigid registration alone. For all patients the mean DSC assessing GTVCT improved from 0.66 (

In the comparison of GTVCT contours the use of deformable registration resulted in a greater reduction in the COM displacement in 8 of the 10 patients, and an improvement in DSC for 9 of the 10 patients compared with rigid registration alone. For all patients the mean DSC assessing GTVCT improved from 0.66 ( with the

with the  ) to 0.82 (

) to 0.82 ( with the

with the  ) (p = 0.008). However the reduction observed in the mean COM displacement, from 6.9 mm (

) (p = 0.008). However the reduction observed in the mean COM displacement, from 6.9 mm ( with the

with the  ) to 3.6 mm (

) to 3.6 mm ( with the

with the  ) failed to reach significance (p = 0.056). The mean percentage volume change between the

) failed to reach significance (p = 0.056). The mean percentage volume change between the  and the

and the  was 33.5% and this was reduced to a percentage volume change of 18.2% between the

was 33.5% and this was reduced to a percentage volume change of 18.2% between the  and the

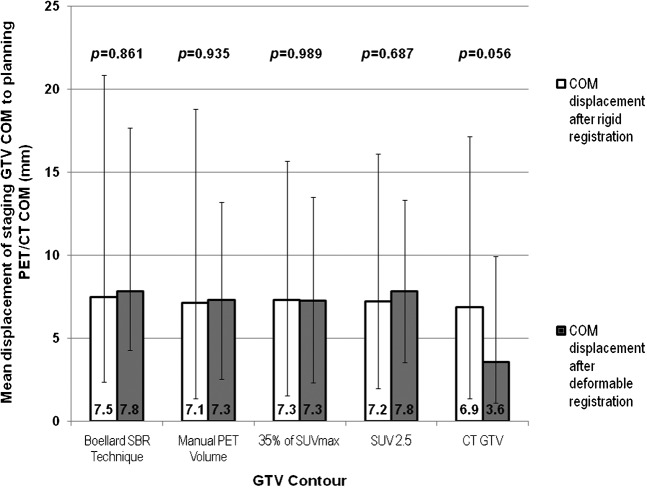

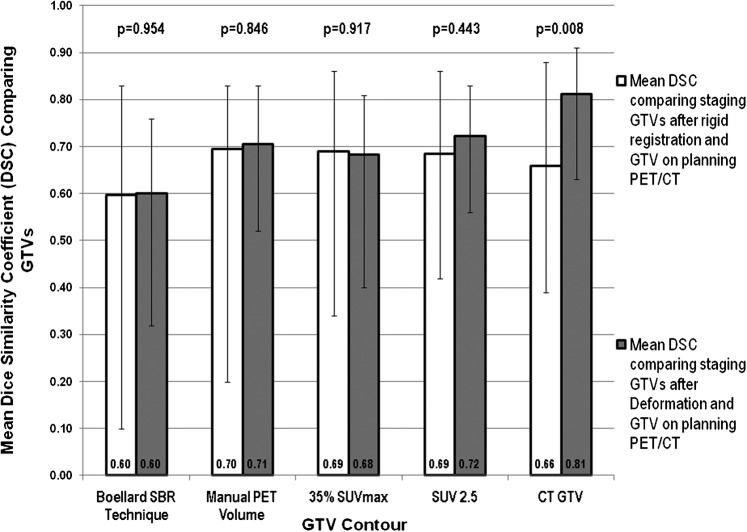

and the  following deformation (p = 0.042), again showing an improved approximation to the planning CT scan using deformation over rigid registration for CT-based contours. In marked contrast, all four PET-based target volumes revealed no similar improvements in registration with deformation over rigid registration. The mean DSC and COM displacements did not demonstrate any significant improvement, with the mean values listed in Figures 2 and 3.

following deformation (p = 0.042), again showing an improved approximation to the planning CT scan using deformation over rigid registration for CT-based contours. In marked contrast, all four PET-based target volumes revealed no similar improvements in registration with deformation over rigid registration. The mean DSC and COM displacements did not demonstrate any significant improvement, with the mean values listed in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Mean centre of mass (COM) displacements from the staging gross tumour volumes (GTVs) after rigid and deformable registration to the planning positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan GTVs. The range is denoted by the error bars, the mean values are shown and the two-tailed significance is listed above each comparison. The mean COM displacement is either increased or not improved after rigid registration for the four PET-based GTVs, suggesting a worsening or no improvement of registration with deformation. However, a reduction in COM for the GTVCT suggests an improvement of registration for this target volume. SUV, standardized uptake value; SBR, source-to-background ratio.

Figure 3.

Mean Dice's similarity coefficients (DSCs) comparing the various gross tumour volumes (GTVs) after rigid and deformable registration with the same GTVs obtained on the planning positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. The range is denoted by the error bars, the mean values are shown and the two-tailed significance is listed above each comparison. There was no significant improvement in DSC with deformation over rigid registration for the four PET-based contours, suggesting no sizeable improvement in position or volume approximation with deformation. There is a significant increase in the mean DSC for the CT-based contour (GTVCT), indicating a mean improvement in alignment and volume with deformation. SUV, standardised uptake value; SBR, source-to-background ratio.

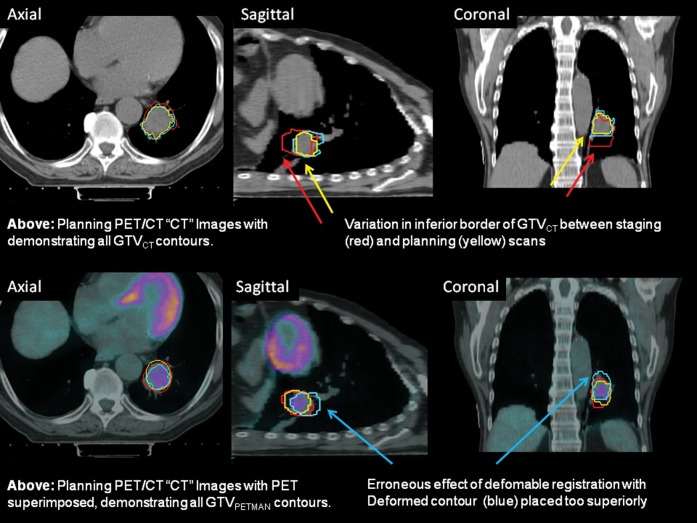

Visual assessments of registration steps for the GTV contours revealed that, for those patients in whom there was a clear improvement in volume correlation for GTVCT but a reduction in DSC for the PET-based contours (GTVPETSBR, GTVSUV2.5, SUV35%SUVMAX, GTVPETMAN), the caudiocranial position of the GTVCT in relation to the PET-based contours was in a different position on the staging scan from that on the RTP scan. An example from Patient 2 is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Axial, sagittal and coronal images from the planning positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan acquired for Patient 2. The upper three images show the CT images alone with the three CT-based (GTVCT) contours. The  is yellow, the

is yellow, the  is red and the

is red and the  is blue. Note the contrasting positions and inferior borders of the

is blue. Note the contrasting positions and inferior borders of the  and the

and the  This may be due to the scan acquisitions being in different phases of the respiratory cycle. CT-based deformation correctly adjusts for that, aligning the

This may be due to the scan acquisitions being in different phases of the respiratory cycle. CT-based deformation correctly adjusts for that, aligning the  in close approximation to the

in close approximation to the  . However, if the scans were acquired in different respiratory phases, then the GTVCT positions relative to PET contours will be different. In the lower three images the

. However, if the scans were acquired in different respiratory phases, then the GTVCT positions relative to PET contours will be different. In the lower three images the  is yellow, the

is yellow, the  is red and the

is red and the  is blue. The rigid registration gives reasonable visual correlation with the

is blue. The rigid registration gives reasonable visual correlation with the  although there is poor correlation between the

although there is poor correlation between the  and the

and the  contours.

contours.

To exclude the possibility that data from 3 patients with sizeable changes in tumour volume between staging and RTP scans (Patients 3, 8 and 10) resulted in poor results for the use of deformable registration, repeat DSC analysis using data from only the remaining 7 patients was performed, and it revealed no differences. For the seven patients without sizeable volume changes, the mean DSC assessing GTVCT improved significantly from 0.69 ( with the

with the  ) to 0.80 (

) to 0.80 ( with the

with the  ) (p = 0.001). However, DSC measurements comparing the PET-based contours for these patients did not improve (GTVPETSBRp = 0.491, GTVSUV2.5

p = 0.946, SUV35%SUVMAX

p = 0.804, GTVPETMANp = 0.370).

) (p = 0.001). However, DSC measurements comparing the PET-based contours for these patients did not improve (GTVPETSBRp = 0.491, GTVSUV2.5

p = 0.946, SUV35%SUVMAX

p = 0.804, GTVPETMANp = 0.370).

Discussion

In this investigation, we have demonstrated that deformable registration improves the overlap of GTV contours transferred from a staging to a planning CT scan. A significant improvement was seen in DSC (p = 0.008) between the comparison of  with

with  and the comparison of

and the comparison of  with

with  . The observed improvement (i.e. reduction) in COM displacements following deformation also suggests that the deformation algorithm used has a benefit over rigid registration alone for CT-based registration. In contrast, similar improvements were not observed using deformable registration for transferring PET-based contours from the staging PET/CT scan, using the CT-based registration to the RTP PET/CT scan as an intermediate step. In a number of patients, the use of deformation led to an increase in COM displacement and a reduction in DSC (Tables 4 and 5).

. The observed improvement (i.e. reduction) in COM displacements following deformation also suggests that the deformation algorithm used has a benefit over rigid registration alone for CT-based registration. In contrast, similar improvements were not observed using deformable registration for transferring PET-based contours from the staging PET/CT scan, using the CT-based registration to the RTP PET/CT scan as an intermediate step. In a number of patients, the use of deformation led to an increase in COM displacement and a reduction in DSC (Tables 4 and 5).

Limited patient numbers

This study has a number of limitations which must be acknowledged. As our analysis was limited to only 10 patients, we may have missed a significant beneficial effect of deformable registration for the PET-based contours. Nevertheless, it was possible to demonstrate a significant improvement in DSC and volumetric approximation in this patient cohort for the CT-based contours and this has been demonstrated in other investigations [20].

Time delay between staging and planning scan acquisitions

A second notable limitation is the variable time scan between the staging and RTP PET/CT scan acquisitions for the patients studied. This variable time frame was often due to a complex referral and assessment pathway. Many of the patients included were initially considered for surgical resection, but were deemed not suitable or fit enough for surgical resection and the assessment for operability introduced delay between staging and RTP scan acquisitions. This variable time frame may permit sizeable tumour growth and hence apparent misregistration, given that this investigation only compared the primary target volume. Ideally, to exclude this source of error, comparison of two PET/CT scans no more than a day apart would be desirable. However, despite sizable GTV changes between the staging and RTP PET/CT scans for three patients, for the other seven patients the GTV size on both scans was similar, suggesting that no sizeable tumour progression (as assessed on CT) occurred. Although changes in tumour size may have an impact on simple volume comparisons, any such impact on COM and DSC comparisons should be minimal as was demonstrated by the similar DSC results when the three patients with sizeable volume differences (Patients 3, 8 and 10) were excluded.

Target volume delineation

The use of target volumes as the comparator to assess the accuracy of the registration technique has two potential limitations. Given that some target volumes were manually delineated (GTVCT and GTVPETMAN), possible intraclinician contouring variation between the scan sets may have led to variable comparisons between the CT and PET components. In this investigation it was hoped that the use of a single clinician for target volume delineation and the use of standardised windowing displays would minimise the potential variability that manual contouring may incur. In addition, the two PET threshold delineation methods (GTVSUV2.5 and GTV35%SUVMAX) and the automated source-to-background ratio (SBR) delineation technique (GTVSBR) used in our study showed very similar results to the GTVPETMAN following rigid and deformable registration. Another limitation of using target volumes as the comparator of the registration similarity is that the results may have been influenced more by changes in the target volume alone, rather than the effect of the registration technique. However, compared with CT-based registration comparisons, thoracic PET scans have a paucity of clearly defined discrete anatomical landmarks on which to assess the accuracy of the registration technique. Hence, in this investigation, we chose to use the most clearly defined thoracic PET structure of relevance, namely the GTV as defined by four different PET-based delineation techniques.

Some possible reasons for a lack of benefit of deformable registration for PET contours can be considered. This may have been due to initial misalignment between the PET and CT components of each PET/CT scan, owing to patient movement between the CT and PET scan acquisitions. However, visual assessment did not reveal the former in this data set. In the studies investigating the use of deformable registration in head and neck cancer, the images obtained were of a static region of the body and for the planning CT scans the patient was immobilised in a custom-made shell [10,11]. Owing to the effects of cardiac and respiratory motion, this is not the case in the thorax. In most PET/CT acquisition protocols, the CT scan is acquired as a fast “snap-shot” image, imaging the entire thorax in seconds. No special breathing instructions were used and no respiratory monitoring was used. Hence, as suggested by the clinical example in Figure 4, the CT component of the staging and RTP PET/CT scans may be acquired at different phases of the respiratory cycle. By contrast, the PET component of the PET/CT scan, depending on the type of scanner and the protocol used, is usually acquired over 2–5 min for each table position. Hence the PET component of the scan contains an element of the respiratory motion of a lung tumour. It has been suggested that this four-dimensional (4D) element of a PET scan might be able to define an internal target volume, compensating for all respiratory motion [16,23]. Thus, with current scanning protocols, a 3D scanning modality (CT) is in effect being combined with a 4D scanning modality (PET). Hence, if the respiratory phase relationship of the CT scan acquired at the staging scan is not identical to that obtained from the planning scan, then deformation of the PET-based contours, using the CT deformation map, may lead to a reduced spatial correlation as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Visual explanation for poor performance of deformation of positron emission tomography (PET)-based contours due to differences in respiratory motion between the scans. The relationship between (a) and (b) is analogous to rigid registration and the relationship between (c) and (d) is analogous to deformation. (a) This represents a staging PET/CT scan, the blue shaded area represents the gross tumour volume (GTV) as delineated on CT and the red outline the internal target volume as delineated on PET. The GTV on CT has been imaged at an extreme of respiration. In (b) for the same patient representing the situation in a planning PET/CT scan, the GTV on the CT has been imaged at the other extreme of respiration. (c) The staging PET/CT is undergoing deformable registration (orange lines represent direction of warp) to the planning PET/CT scan (d). As the deformation is CT based the algorithm attempts to correct for the differences in the CT components for the two scans, the subsequent deformation of the PET internal target volume (green contour) is incorrect and positioned superiorly to the PET internal target volume on the planning scan.

To avoid both the pitfalls of registration between scan sets and the need to acquire both staging and RTP PET/CT scans, some authors have shown that acquiring a single PET/CT scan in the radiotherapy treatment position both for the purposes of baseline staging and for the purposes of simulation may be appropriate [24]. One potential limitation of this approach is that further staging investigations, such as a mediastinal lymph node biopsy, may be required as a result of findings from the combined purpose PET/CT scan and this may introduce delay between the acquisition of the RTP PET/CT scan and commencement of treatment. Furthermore, many patients referred for radiation therapy will already have had baseline PET/CT scanning prior to referral for radiotherapy.

If registration of a staging PET scan is to be used as a means of incorporating PET in RTP simulation, one potential solution to overcome this issue is acquisition of the CT imaging with 4D information and subsequent registration of the staging PET scan to the 4D CT scan. Grgic et al [8] demonstrated that rigid registration between staging PET and RTP CT was most optimal when the RTP CT was acquired in the mid-ventilation phase of the respiratory cycle. This is intuitive, as the mid-ventilation position will have the least average position displacement when comparing the RTP CT with the staging imaging. However, for registration of a staging PET scan to a 3D RTP simulation CT scan, given the findings of this investigation, the use of rigid registration is recommended.

Conclusion

Although deformable registration improves the accuracy of CT-based registration between scan sets acquired on the same patient, transfer of contours from a staging PET scan to a standard 3D radiotherapy planning CT scan using the same deformation warp does not provide consistent improved registration. We recommend that, if conventional 3D PET/CT scan is to be used for CT simulation purposes in NSCLC, it is best performed as a dedicated radiotherapy planning scan with the patient positioned in the treatment position. If this is not possible and a staging PET/CT scan is to be registered to a non-respiration correlated 3D radiotherapy planning CT scan, then rigid registration should be used to transfer contours as best possible.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical advice and many useful suggestions provided for the software tool from Dr Timothy Fox and Anthony Waller of Velocity Medical Solutions, Atlanta, GA.

Funding for Dr Hanna was kindly provided by the Research and Development Office, Northern Ireland Health and Social Services. Dr Hanna also received funding from the Keith Durrant Travelling Fellowship, Royal College of Radiologists, London, towards this work. The VU University Medical Centre has a research collaboration with Velocity Medical Solutions, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer V2.2010. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2010 [cited 2010 March 6]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacManus MP, Wong K, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, Wirth A, Ball DL. Early mortality after radical radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: comparison of PET-staged and conventionally staged cohorts treated at a large tertiary referral centre. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002;52:351–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanna GG, McAleese J, Carson KJ, Stewart DP, Cosgrove VP, Eakin RL, et al. 18F-FDG PET-CT simulation for non-small cell lung cancer: What is the impact in patients already staged by PET-CT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;77:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grills IS, Yan D, Black QC, Wong CY, Martinez AA, Kestin LL. Clinical implications of defining the gross tumor volume with combination of CT and 18FDG-positron emission tomography in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;67:709–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Ruysscher D, Wanders S, Minken A, Lumens A, Schiffelers J, Stultiens C, et al. Effects of radiotherapy planning with a dedicated combined PET-CT-simulator of patients with non-small cell lung cancer on dose limiting normal tissues and radiation dose-escalation: a planning study. Radiother Oncol 2005;77:5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson KJ, Young VA, Cosgrove VP, Jarritt PH, Hounsell AR. Personnel radiation dose considerations in the use of an integrated PET-CT scanner for radiotherapy treatment planning. Br J Radiol 2009;82:946–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestle U, Walter K, Schmidt S, Licht N, Nieder C, Motaref B, et al. 18F-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for the planning of radiotherapy in lung cancer: high impact in patients with atelectasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999;44:593–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grgic A, Nestle U, Schaefer-Schuler A, Kremp S, Kirsch CM, Hellwig D. FDG-PET-based radiotherapy planning in lung cancer: Optimum breathing protocol and patient positioning – an intraindividual comparison. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;73:103–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaus MR, Brock KK, Pekar V, Dawson LA, Nichol AM, Jaffray DA. Assessment of a model-based deformable image registration approach for radiation therapy planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:572–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ireland RH, Dyker KE, Barber DC, Wood SM, Hanney MB, Tindale WB, et al. Nonrigid image registration for head and neck cancer radiotherapy treatment planning with PET/CT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:952–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang AB, Bacharach SL, Yom SS, Weinberg VK, Quivey JM, Franc BL, et al. Can positron emission tomography (PETP or PET/computed tomography (CT) acquired in a nontreatment position be accurately registered to a head-and-neck radiotherapy planning CT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;73:578–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacManus M, Nestle U, Rosenzweig KE, Carrio I, Messa C, Belohlavek O, et al. Use of PET and PET/CT for radiation therapy planning: IAEA expert report 2006–2007. Radiother Oncol 2009;91:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mountain CF. Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 1997;111:1710–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarritt PH, Hounsell AR, Carson KJ, Visvikis D, Cosgrove VP, Clarke JC, et al. Use of combined PET/CT images for radiotherapy planning: initial experiences in lung cancer. Br J Radiol 2005;Suppl 28:33–40 [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacManus MP, Hicks RJ. Where do we draw the line? Contouring tumors on positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;71:2–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okubo M, Nishimura Y, Nakamatsu K, Okumura M, Shibata T, Kanamori S, et al. Static and moving phantom studies for radiation treatment planning in a positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET/CT) system. Ann Nucl Med 2008;22:579–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nestle U, Kremp S, Schaefer-Schuler A, Sebastian-Welsch C, Hellwig D, Rübe C, et al. Comparison of different methods for delineation of 18F-FDG PET-positive tissue for target volume definition in radiotherapy of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med 2005;46:1342–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boellaard R, Krak NC, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA. Effects of noise, image resolution, and ROI definition on the accuracy of standard uptake values: a simulation study. J Nucl Med 2004;45:1519–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattes D, Haynor DR, Vesselle H. Non-rigid multi modality image registration. Med Imaging 2001;4322:1609 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brock KK, Deformable Registration Accuracy Consortium Results of a Multi-Institution Deformable Registration Accuracy Study (MIDRAS). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76:583–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dice LR. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 1945;26:297–302 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou KH, Warfield SK, Bharatha A, Tempany CM, Kaus MR, Haker SJ, et al. Statistical validation of image segmentation quality based on a spatial overlap index. Acad Radiol 2004;11:178–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caldwell CB, Mah K, Skinner M, Danjoux CE. Can PET provide the 3D extent of tumor motion for individualized internal target volumes? A phantom study of the limitations of CT and the promise of PET. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;55:1381–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Boersma L, Buijsen J, Wanders S, Hochstenbag M, et al. PET-CT-based auto-contouring in non-small-cell lung cancer correlates with pathology and reduces interobserver variability in the delineation of the primary tumour and involved nodal volumes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;68:771–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]