Abstract

Imaging morphology and function of the right heart is of paramount importance in patients with adult congenital heart disease, since right ventricular dysfunction is associated with adverse cardiac events. Cardiac MRI has been shown to be a powerful tool for the non-invasive precise assessment of right ventricular and valvular dysfunction. Differential diagnoses of congenital heart disease characterised by, or combined with, right heart dilatation are diverse and necessitate a systematic approach.

Right heart dilatation in congenital heart disease (CHD) is a condition mostly observed in the presence of a significant left to right shunt owing to an atrial septal defect (ASD), a partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) or in the post-surgical course of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).

Infrequent causes of right heart dilatation in CHD include tricuspid valve (TV) and pulmonary valve (PV) regurgitation in cases of dysplastic valves and Ebstein's anomaly, vascular lesions, such as coronary cameral fistulas, and myocardial disorders, such as Uhl's anomaly, and ventricular diverticula or aneurysms (Table 1).

Table 1. Causes of right heart dilatation in adult congenital heart disease.

| Origin | |

| Shunt | Secundum atrial septal defect |

| Primum atrial septal defect | |

| Sinus venosus defect | |

| Partial anomalous pulmonary return | |

| Extracardial shunts (pulmonary/systemic arteriovenous connections) | |

| Coronary artery fistula to the coronary sinus/right atrium/right ventricle | |

| Valvular | Tricuspid valve |

| Ebstein's anomaly | |

| Dysplasia | |

| Prolapse | |

| Pulmonary valve | |

| Dysplastic valve | |

| Post-operative valvular insufficiency after tetralogy of Fallot repair or following homograft replacement | |

| Myocardial | Morbus Uhl |

| Ventricular aneurysm/diverticulum |

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in CHD provides an excellent morphological overview by using spin-echo (black blood) sequences and allows accurate and reliable assessment of both valve and right ventricular function using steady-state free-precession (SSFP) sequences. The ventricular volumes are calculated according to the rule of Simpson from SSFP (cine sequences during end-systole and end-diastole) [1]. In the clinical scenario of right ventricular dilatation it is useful to additionally acquire a stack of two chamber short-axis images to evaluate ventricular function and to qualitatively estimate the right systolic pressure based on the configuration of the ventricular septum. Phase contrast imaging in CMR uses motion-induced phase shifts for the measurement of local flow velocities within cardiac or vascular structures. If using phase contrast imaging for the evaluation of flow velocities, or for the calculation of flow volumes, the imaging plane must be located perpendicular to the axis of the vessel lumen of interest.

The aim of this pictorial review is to illustrate the differential diagnoses of right heart dilatation in adults with CHD imaged by CMR.

Causes of right heart dilatation in adult CHD at CMR

Atrial septal defect

ASD is the most common defect in CHD with left to right shunting. Clinical symptoms and the age at which these symptoms appear are highly variable. Exertional dyspnoea and exercise-related fatigue are the most common presenting symptoms. Atrial fibrillation or flutter as a result of right atrial dilatation is normally observed in patients over 40 years of age. Less common first presenting symptoms are decompensated right heart failure (elderly patients) and paradoxical embolism.

There are three major types of ASD: ostium primum, ostium secundum and sinus venosus defects. The most common type is secundum ASD, which is located in the middle of the atrial septum within the fossa ovalis (Figure 1). Ostium primum defects are located in the lower part of the septum and are often accompanied by a cleft in the left-sided atrioventricular valve. Sinus venosus defects are better described as an overriding of the mouth of the superior or inferior caval vein with bilateral connections to the right and left atrium, which can result in an extra-septal interatrial connection (Figure 2). In the majority of these cases, a PAPVR is associated with sinus venosus defects. CMR helps to define cardiac anatomy, to calculate ventricular volumes and to estimate the shunt volume [2]. Shunt quantification can be performed by using left and right ventricular volumetry during systole and diastole as well as flow measurements within the main pulmonary artery and the ascending aorta. The shunt volume is defined as the difference between the right and the left ventricular stroke volume and is usually expressed as a ratio between the pulmonary flow (Qp) and the systemic flow (Qs). If this ratio exceeds 1.5:1 an interventional or surgical correction of the shunt is usually indicated. CMR also offers the possibility to directly quantify the shunt volume by means of direct en face velocity-encoded imaging at the site of the interatrial septum [3].

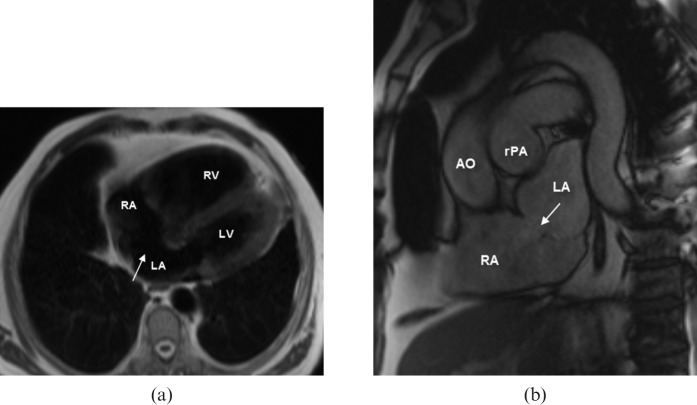

Figure 1.

A 79-year-old patient with symptoms of exercise-related dyspnoea and right ventricular dilatation on echocardiography. (a) Black blood and (b) steady-state free-precession (SSFP) MR images show a “classic” secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) with a diameter of 18 mm (arrows). Calculated left to right shunt ratio was 2:1 and shunt volume was 61 ml. AO, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; rPA, right pulmonary artery.

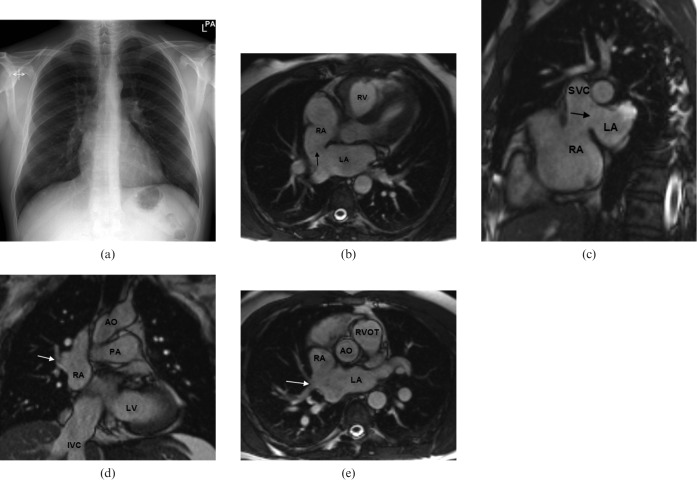

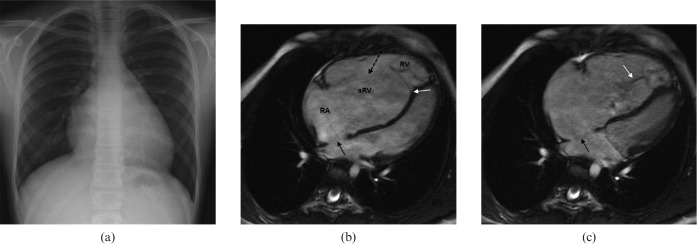

Figure 2.

A 44-year-old male patient with symptoms of exercise-related shortness of breath. (a) Conventional radiograph of the chest revealed borderline prominent hilar vessels. (b,c) Steady-state free-precession (SSFP) MR images show a large superior sinus venosus atrial septal defect (ASD) (black arrows). (d,e) Associated partial anomalous pulmonary return of the right upper lobe pulmonary vein (white arrows). Qp:Qs ratio was 2:1. AO, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

CMR including gadolinium contrast-enhanced MR angiography has further proved to be superior to transthoracal and transoesophageal echocardiography in establishing the diagnosis of PAPVR associated with an ASD.

Pulmonary valve dysfunction

With major advances in paediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery, increasing numbers of patients, who underwent balloon dilatation or cardiac surgery for pulmonary stenosis, now reach adulthood with the need for follow-up examinations.

Pulmonary regurgitation (PR) is common in the post-operative course of TOF and after intervention for pulmonary stenosis, which results in right ventricular dilatation owing to increased volume load (Figure 3). PR is usually well tolerated for a long time. Clinical manifestations include exercise intolerance, symptoms of congestive heart failure, atrial/ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Thus, follow-up in TOF is also focused on PR. If a transannular or anterior outflow tract patch is used in the repair of TOF, PV function nearly always becomes affected because there is akinesia within the right ventricular outflow tract at the site of the patch. Additionally, in TOF there may be an accompanying pulmonary branch stenosis. This should be evaluated by flow velocity measurements within the main branches of the pulmonary artery.

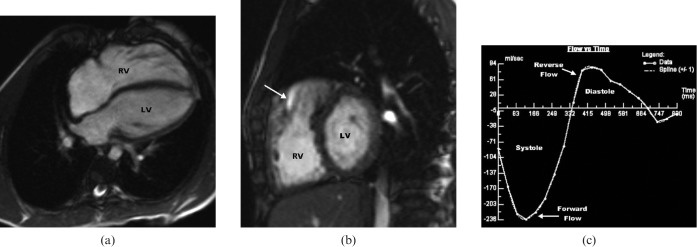

Figure 3.

Steady-state free-precession (SSFP) cardiac MRI of a 23-year-old male patient who underwent repair of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) at 3 years old. (a) Long-axis four-chamber view shows distinct right ventricular dilatation. Right ventricular ejection fraction is reduced to 39%. (b) Right ventricular dilation on short-axis view. Note the typical anterior-located jet indicating reverse flow during early diastole in the right ventricular outflow tract on parasagittal image (white arrow). (c) Flow vs time curve of a pulmonary insufficiency in TOF indicating a pulmonary regurgitation fraction of 32% during diastole (area above the x-axis). LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Subsequent to a Ross procedure, where the patient's diseased aortic valve is replaced with his or her own pulmonary valve and the pulmonary valve is then replaced by a homograft, 10% of all patients develop significant homograft stenosis that necessitates reintervention (Figure 4). The same applies for homografts implanted for other conditions (e.g. pulmonary stenosis in TOF). CMR of RV function and flow velocity mapping is advantageous in the follow-up of these patients for planning further treatment [4, 5].

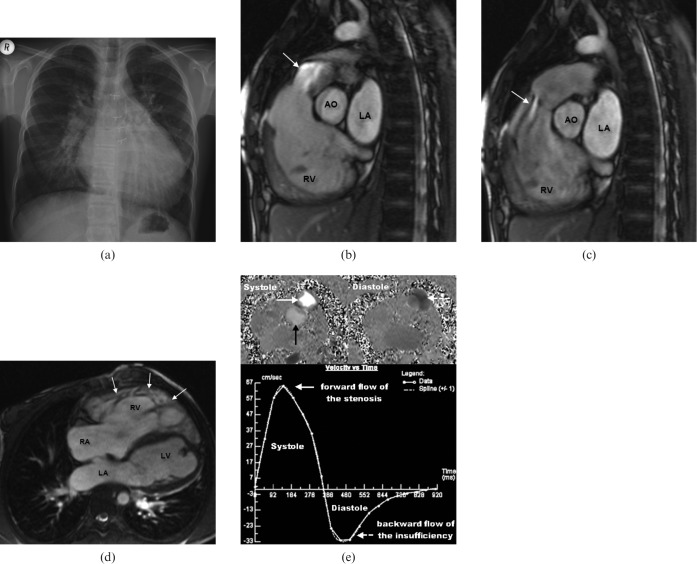

Figure 4.

Right heart dilatation in a 19-year-old female patient who underwent a Ross procedure at 4 years old. (a) Conventional radiograph of the chest reveals cardiomegaly. (b,c) Steady-state free-precession (SSFP) images show a distinct flow void in the right ventricular outflow tract, both during systole (arrow) and diastole (arrow), accounting for a pulmonary stenosis (b) combined with a valvular insufficiency of the homograft (c). Pulmonary regurgitation fraction was 52% (severe). (d) Long-axis four-chamber view shows distinct right ventricular hypertrabeculation (white arrows) owing to elevated pressure load. (e) Flow velocity mapping of the pulmonary stenosis (white arrow) shows high systolic peak flow velocity (Vmax = 218 cm s-1; increased if Vmax exceeds 150 cm s-1) compared with the ascending aorta (Vmax = 120 cm s-1) (black arrow) during systole and reverse flow during diastole (white dotted arrow). Mean velocity vs time diagram summarises these findings and demonstrates a valvular stenosis combined with valvular insufficiency of the pulmonary valve. Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Tricuspid valve dysfunction

In Ebstein's anomaly, which accounts for 1% of all congenital cardiac defects, the septal leaflet of the TV is displaced apically, which leads to a downward displacement of the functional annulus of the TV. This results in a partial atrialisation of the RV and the enlarged right atrium (RA) is further dilated by additional TV incompetence (Figure 5). An associated ASD is common.

Figure 5.

Ebstein's anomaly in a 22-year-old female patient. (a) Conventional radiograph of the chest reveals right atrial enlargement. (b,c) Long-axis four-chamber view: the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve originates at the lower part of the interventricular septum, leading toward a partial atrialisation of the right ventricle (white arrow) and tricuspid valve insufficiency (black dotted arrow). The right atrium appears consecutively enlarged and the functional right ventricle is small. Black arrows (b,c) demonstrate an associated atrial septal defect. (c) Additional jet during systole originating from the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve probably caused by a fenestrated leaflet. AO, aorta; RA, right atrium; aRV, atrialised right ventricle; RV, “true” right ventricle.

The haemodynamics include a small functional RV with increased impedance to filling and a TV insufficiency that results in an elevated filling pressure of the RA. If there is an additional ASD there may be right to left shunting. Depending on the anatomical severity of the malformation, clinical manifestations include right-sided heart failure, cyanosis, arrhythmia and sometimes paradoxical embolism [6].

In case of absence of the typical imaging findings of Ebstein's anomaly, but right heart dilatation owing to a single TV insufficiency, differential diagnoses include TV prolapse, dysplastic right heart starting as a singular RV enlargement and single valvular deformity of the TV [7].

Myocardial causes

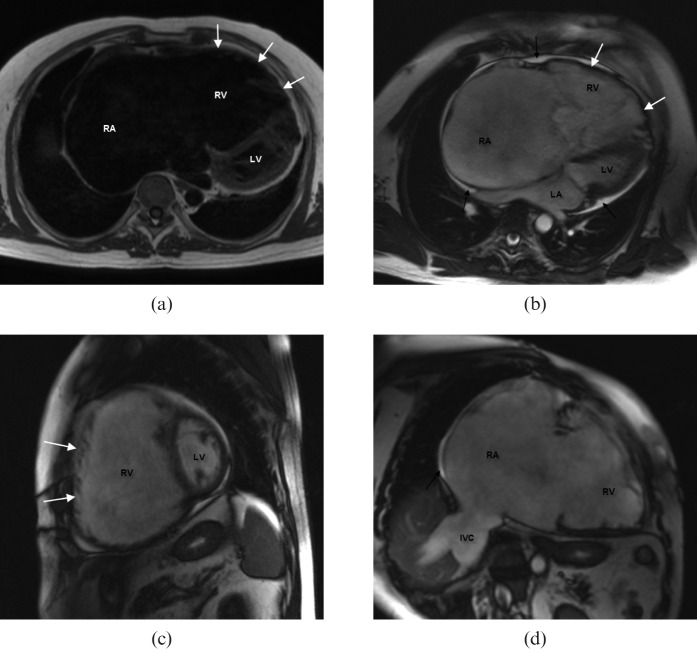

Morbus Uhl was initially described in 1952 and is defined as complete or partial absence of the myocardial layer of the RV that results in massive enlargement of the RV. Patients present with signs of severe right heart failure associated with peripheral oedema, pleural and pericardial effusions, or arrhythmias. The aetiology remains unclear, but there are two theories, one based on the primary non-development of the myocytes, and the other on the apoptosis of the myocytes [8]. CMR imaging findings in Morbus Uhl include a singular right ventricular dilatation with absence of the right ventricular myocardium, hypokinetic wall movement and associated TV insufficiency (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A 59-year-old male patient who presented with a history of atrial flutter and signs of cardiac failure. (a) Black blood and (b–d) steady-state free-precession (SSFP) cardiac magnetic resonance images illustrate a distinct dilatation of the right atrium and the right ventricle, with complete absence of the right ventricular myocardial layer (white arrows). (a,b) The left ventricle is impressed and displaced laterally on long-axis four-chamber views. Assessment of right ventricular function delivers an ejection fraction of 32% with an end-diastolic volume of 287 ml and an end-systolic volume of 196 ml, accompanied by severe tricuspid valve insufficiency. (b–d) Pericardial effusion (black arrows) and dilation of the inferior vena cava and the liver veins are evidence of chronic cardiac failure. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Diverticula and aneurysm

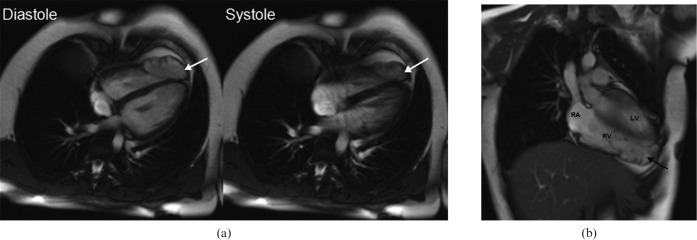

Diverticula and aneurysms of the RV are rare and clinically silent in most cases, normally discovered at the time of evaluation of a cardiac murmur or echocardiogram abnormalities. Palpitations and chest discomfort have been described. Ventricular outpouching on cine images should be used to distinguish these two entities on CMR. Contractility of the involved wall segment accounts for the diagnosis of a diverticulum, whereas dys- to akinesia accounts for a ventricular aneurysm (Figure 7) [9]. Cardiac diverticla are often associated with thoracic midline defects like the Pentalogy of Chantrell. If not, the aetiology is assumed to be associated with ischaemic or infectious focal weakening of the ventricular wall during embryogenesis.

Figure 7.

A 25-year-old female patient who presented with symptoms of palpitations. (a,b) Steady-state free-precession bright blood images during diastole and systole demonstrated a diverticulum at the apex of the right ventricle (white arrows). Reduced contractility of the diverticulum was observed during systole, but there is no outpouching of the right ventricular wall. Right ventricular volumes and right ventricular function appear to be normal. (b) Coronal view of the diverticulum at the right ventricular apex (black arrow). LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Conclusion

Assessment of RV morphology and function is of paramount importance in adults with CHD. CMR has proved to be a powerful tool in the evaluation of right ventricular functional parameters. To obtain the maximum amount of information from imaging, precise knowledge of the diverse differential diagnoses and their underlying haemodynamics is recommended.

References

- 1.Alfakih K, Reid S, Jones T. Assessment of ventricular function and mass by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol 2004;14:1813–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debl K, Djavidani B, Buchner S, Heinicke N, Poschenrieder F, Feuerbach S, et al. Quantification of left-to-right shunting in adult congenital heart disease: phase-contrast cine MRI compared with invasive oximetry. Br J Radiol 2009;82:386–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson LE, Crowley AL, Heitner JF, Cawley PJ, Weinsaft JW, Kim HW, et al. Direct en face imaging of secundum atrial septal defects by velocity-encoded cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients evaluated for possible transcatheter closure. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;1:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grotenhuis HB, de Roos A, Ottenkamp J, Schoof PH, Vliegen HW, Kroft LJ. MR imaging of right ventricular function after the Ross procedure for aortic valve replacement: initial experience. Radiology 2008;246:394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grothoff M, Spors B, Abdul-Khaliq H, Gutberlet M. Evaluation of postoperative pulmonary regurgitation after surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot: comparison between Doppler echocardiography and MR velocity mapping. Pediatr Radiol 2008;38:186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attenhofer Jost CH, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Edwards WD, Danielson GK. Ebstein's anomaly. Circulation 2007;115:277–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammash NM, Warnes CA, Connolly HM, Danielson GK, Seward JB. Mimics of Ebstein's anomaly. Am Heart J 1997;134:508–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhl HS. Uhl's anomaly revisited. Circulation 1996;93:1483–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marijon E, Ou P, Fermont L, Le Bidois J, Sidi D, et al. Diagnosis and outcome in congenital ventricular diverticulum and aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006l;131:433–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]