Abstract

Objectives

To determine the frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow using colour Doppler sonography (CDS) on hepatic haemangiomas with arterioportal shunt (APS), and to investigate possible factors that may affect the capability of CDS to depict such findings.

Methods

The study included 45 patients (35 men, 10 women; mean age, 56 years) with hepatic haemangiomas with APS on CT or MRI. Locating the tumour on greyscale sonography, the depth, size and echogenicity of the tumour were evaluated. CT or MR images were evaluated for fatty liver. CDS was performed to determine the presence of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow. Differences in frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow according to the depth, size, echogenicity and fatty liver were evaluated by Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact test.

Results

On CDS, intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were found in 66.7% and 60%, respectively. The tumour depth was the significant variable that affected the capability of CDS to depict such findings. The frequencies of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were as high as 88% and 80% for shallow (≤30 mm) lesions, and they were 40% and 35% for deep (>30 mm) lesions (p=0.0012; p=0.0051).

Conclusion

CDS can commonly depict intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow in patients with hepatic haemangiomas with APS. Therefore, CDS should be routinely performed when an incidental mass is encountered during the screening sonography, especially when the lesion is shallow.

Hepatic haemangiomas are frequently found incidentally on screening sonography; therefore, it is important to characterise their sonographic appearances.

The value of colour Doppler sonography (CDS) for the evaluation of hepatic haemangioma has been generally underestimated, presumably because most typical haemangiomas have slow intratumoural flow below the sensitivity limits of CDS [1,2]. However, the blood flow pattern of haemangioma differs from tumour to tumour depending on the internal architecture or collective size of the vascular spaces [3], and high-flow haemangiomas, usually (83–89%) accompanying arterioportal shunt (APS), constitute approximately 29–35% of hepatic haemangiomas [4,5]. In contrast to the dissatisfying results in typical slow-flow haemangiomas, it has been reported that, in six cases of angiographically proven haemangiomas with APS, CDS could demonstrate large penetrating arteries, multiple intratumoural flow signals, reversed portal flow within the tumours and hepatofugal portal flow around the tumours [6]. However, the small sample size may have limited the value of this study, and we assume that the capability of CDS to depict the intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow in haemangiomas with APS may have depended on various factors.

Thus, the purposes of our study were to determine the frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow on CDS of hepatic haemangiomas with APS and to investigate possible factors that may affect the capability of CDS to depict such findings.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was approved by our institutional review board, and informed consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Among 49 consecutive patients in whom CDS was performed after the diagnosis of hepatic haemangioma with APS via CT or MRI between September 2004 and December 2007 at our institution, 4 were excluded because their images had been used for other studies; the remaining 45 were enrolled in this study. There were 35 men and 10 women, aged 32–79 years (mean±standard deviation [SD], 56±13 years). The 45 patients had 76 haemangiomas, of which 63 were accompanied by APS. Because inclusion of multiple lesions per patient may have led to a data clustering bias, we selected one lesion per patient for this study. For this purpose, one of the authors, as a study organiser, reviewed all CT, MR and CDS images and selected one tumour per patient with the largest area of wedge-shaped temporal peritumoural enhancement during the hepatic arterial phase (HAP).

CT and MRI

Diagnosis of hepatic haemangiomas were made based on characteristic findings on CT scans (n=41) or MRI (n=4) and no interval change on follow-up imaging (>1 year). Characteristic CT or MR findings were as follows: (a) the lesions showed strong peripheral, nodular or homogeneous enhancement that was isoattenuating with the aorta during the HAP; and (b) the lesions showed centripetal fill-in or persistent homogeneous enhancement that was iso-attenuating with enhanced intrahepatic vessels during the portal venous phase (PVP). Characteristic MR findings also included the lesions showing high signal intensity similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid on T2 weighted images. An associated APS was diagnosed when there was wedge-shaped temporal peritumoural enhancement during the HAP and iso-attenuation or slight hyperattenuation in that area during the PVP.

CT scans were obtained on multidetector row CT scanners (LightSpeed QX/i; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI [n=20] or Somatom Sensation 16; Siemens, Forchheim, Germany [n=21]). After obtaining unenhanced CT scans, 120–150 ml of iopromide (Ultravist 300 or 370; Schering, Berlin, Germany) was injected through an 18- or a 20-gauge intravenous catheter inserted into a forearm vein, at a flow rate of 2.5–3 ml s–1, using a mechanical injector. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scans were obtained with a two-phase protocol (n=13) during the HAP and PVP or a triple-phase protocol (n=28) during the HAP, PVP and delayed phase. HAP imaging was initiated within 25 s after enhancement of the descending aorta reached 100 HU, with a bolus-tracking technique (Smart Prep; GE Medical Systems or CARE-Bolus; Siemens). PVP and delayed-phase imaging were initiated 72 s and 3 min after contrast injection. MR examinations were performed on a 1.5 T system (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany [n=4]). After acquisition of conventional T1 and T2 weighted images as well as chemical shift gradient-echo images with in-phase and opposed-phase acquisitions, dynamic contrast-enhanced T1 weighted MRI was performed 10, 50, and 180 s after administration of 30 ml (0.2 mmol kg–1) of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Schering [n=2]) or 30 ml (0.2 mmol kg–1) of gadobenate dimeglumine (Gd-BOPTA; MultiHance, Schering) (n=2), using a fast low-angle shot sequence.

CT or MR images were evaluated for fatty infiltration in background liver parenchyma. Fatty liver was diagnosed on unenhanced CT when the attenuation of the liver was less than 40 HU or at least 10 HU less than that of the spleen [7-9]. On MR chemical shift gradient-echo imaging, it was diagnosed when there was a significant signal drop on opposed-phase images compared with in-phase images.

Colour Doppler sonography

CDS examinations were performed by two board-certified abdominal radiologists (>5 years’ experience each) on commercially available US equipment such as HDI 5000 or iU22 units (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA [n=27]) and Sequoia 512 (Acuson, Mountain View, CA [n=18]), with a 2–4 MHz or 1–4 MHz curved array transducer.

On greyscale sonography, the depth, size and echogenicity of the tumour were evaluated. The lesion depth was defined as the ultrasound beam path distance before encountering the lesion, and was measured between the surface of the probe and lesion on a vertical line parallel to the ultrasound beam. Because lesion depth may vary depending on scanning (e.g. subcostal vs intercostal), it was defined as the shortest beam path that was suitable for further CDS. Each haemangioma was arbitrarily categorised as a shallow (≤30 mm) or deep (>30 mm) lesion. The size of the haemangioma was measured with internal callipers of the unit in real time or manually measured on sonograms where the lesion appeared largest using a picture archiving and communicating system (PACS; Petavision Hyundai Information Technology, Seoul, Korea). The echogenicity of the haemangioma was compared with hepatic parenchyma, and each tumour was categorised as a hypoechoic, isoechoic or hyperechoic lesion.

Then, real-time CDS was performed to identify the colour flow signals from the feeder and the draining vein of the tumour to determine the presence of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow. The colour Doppler parameters were individually adjusted for each patient.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with commercially available standard statistical software (SPSS for Windows version 12.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Differences in the frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow according to the background fatty liver were evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. Student’s t-test was used to analyse whether there were differences in the frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow on CDS according to the depth and size of the tumours. The differences between shallow and deep lesions and that according to tumoural echogenicity were evaluated by the Fisher’s exact test. Significance was indicated if a two-tailed p value was <0.05.

Results

On CDS, intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were found in 30 (66.7%) and 27 (60%) of 45 haemangiomas with APS. All 27 tumours with peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow also showed intratumoural flow. Representative cases are illustrated in Figures 1–2.

Figure 1.

Hepatic haemangioma with arterioportal shunt in a 63-year-old man. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scans during the hepatic arterial phase show wedge-shaped peritumoural enhancement (arrowheads), suggestive of arterioportal shunt, around high-flow haemangioma in the subcapsular area of the right hepatic lobe. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT scans during the portal venous phase show wedge-shaped peritumoural enhancement (arrowheads), suggestive of arterioportal shunt, around high-flow haemangioma in the subcapsular area of the right hepatic lobe. (c) Colour Doppler sonogram demonstrates prominent intratumoural flow (arrowheads). Also noted are the large feeding artery (small arrows), and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow (large arrows), probably due to arterioportal shunt. (d) Doppler spectrogram shows positive signals from the adjacent feeder.

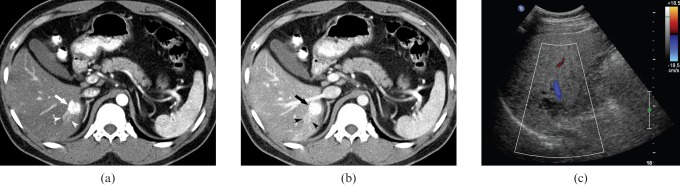

Figure 2.

Hepatic haemangioma with arterioportal shunt in a 32-year-old man. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scans of liver during the hepatic arterial phase show high-flow haemangioma (arrow) with small wedge-shaped peritumoural enhancement (arrowheads), suggestive of arterioportal shunt, deep in the right hepatic lobe. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT scans of liver during the portal venous phase show high-flow haemangioma (arrow) with small wedge-shaped peritumoural enhancement (arrowheads), suggestive of arterioportal shunt, deep in the right hepatic lobe. (c) No intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow is appreciated on colour Doppler sonogram.

Fatty liver was diagnosed in 20 patients (44.4%). Both intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were seen in 13 haemangiomas with background fatty liver (65%). Intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were seen in 17 and 14 tumours without background fatty liver (68% and 56%). The frequency of intratumoural flow or peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow was related to the presence of fatty infiltration in the background liver parenchyma (p=1.00, p=0.76).

The haemangiomas ranged from 9 to 129 mm in depth (mean±SD, 37.1±22.9 mm). The depth of haemangiomas with intratumoural flow ranged from 9 to 68 mm (29.1±12.4 mm), and that of the tumours without intratumoural flow was from 21 to 129 mm (53.3±30.3 mm). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p<0.0001). The depth of haemangiomas with peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow ranged from 9 to 68 mm (29.3±13 mm), and that of the tumours without peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow from 21 to 129 mm (49.0±29.3 mm). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p=0.0036). 25 tumours were categorised as shallow lesions and the other 20 as deep lesions. Whereas intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were found in 22 (88%) and 20 (80%) shallow lesions, such findings were found in 8 (40%) and 7 (35%) deep lesions. Both intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were more commonly demonstrated in shallow lesions than in deep lesions (p=0.0012, p=0.0051).

The haemangiomas ranged from 8 to 121 mm in size (29.4±24 mm). The size of haemangiomas with intratumoural flow on CDS ranged from 8 to 121 mm (33.7±27 mm), and that of tumours without intratumoural flow from 8 to 63 mm (20.7±13.7 mm). The size of haemangiomas with peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow on CDS ranged from 8 to 121 mm (33.8±27.5 mm), and that of the tumours without peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow from 8 to 63 mm (22.7±16.1 mm). The frequency of intratumoural flow or peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow was not related to the tumour size (p=0.09, p=0.13).

The haemangiomas were hypoechoic in 32 lesions, isoechoic in 5 and hyperechoic in 8 when compared with hepatic parenchyma. However, the frequency of intratumoural flow or peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow was not related to the tumoural echogenecity (p=0.33, p=0.91).

Discussion

Besides haemangiomas with APS, CDS can demonstrate intratumoural blood flow in many hypervascular hepatic tumours, such as hepatocellular carcinomas, focal nodular hyperplasias and hepatic adenomas [10-13]. Therefore, a demonstration of intratumoural blood flow on CDS may not allow the specific diagnosis of various hypervascular hepatic tumours except when there is a specific pattern, e.g. a centrifugal, spokewheel pattern of pulsatile flow in focal nodular hyperplasias [12]. However, with the exception of haemangiomas with APS and hepatocellular carcinomas, the peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow on CDS is an uncommon finding among various hypervascular tumours, to the best of our knowledge. Hepatofugal portal flow associated with hepatocellular carcinoma is usually seen in cases with tumoural thrombus in the portal vein lumen [14,15]. Therefore, the presence of peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow on CDS in the absence of portal vein thrombus may be an important sign that enhances the suspicion of hepatic haemangioma with APS. Nevertheless, it should also be kept in mind that peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow without vigorous intratumoural flow may be associated with hepatic venous outflow obstruction caused by any tumefactive lesion.

In our series, CDS commonly enabled us to demonstrate intratumoural flow (66.7%) and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow (60%) in patients with hepatic haemangiomas with APS, and the tumour depth was the significant variable that affected the capability of CDS to depict such findings. Although the frequencies of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow were as high as 88% and 80% for shallow (≤30 mm) lesions, they were 40% and 35% for deep (>30 mm) lesions (p=0.0012, p=0.0051). Presumably, these results are attributed to the fact that Doppler signals from the blood flow in deep hepatic lesions are often too weak to be displayed because the intensity of ultrasound beam is attenuated with tissue penetration [16,17]. Fatty infiltrations of background liver may attenuate the ultrasound beam with tissue penetration. Therefore, it may be expected that the presence of fatty liver may limit the sensitivity of CDS, but our study showed that the frequency of intratumoural flow or peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow was not related to fatty liver. Indeed, CDS may not be compromised in patients with fatty liver when the lesion is shallow because the ultrasound beam will not have been subject to much attenuation before entering the lesion. By contrast, when a lesion is deeply situated, the ultrasound beam may be significantly attenuated before entering the lesion, but the sensitivity of CDS is also limited by the tumour depth itself. Therefore, it is difficult to separate the influence of fatty liver. In our series, there was no statistically significant relationship between the echogenicity of the tumour and the sensitivity of CDS for intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow but approximately 70% (32/45) of the tumours were hypoechoic, despite the fact that haemangiomas are normally expected to have a hyperechoic appearance. This was consistent with previous reports, which showed that high-flow haemangiomas with arterioportal shunt tend to have sonographically hypoechoic appearances [18]. Therefore, we recommend that sonographers pay attention to CDS appearances of the lesions to suggest a possibility of high-flow haemangiomas with arterioportal shunt, especially when encountered with hypoechoic tumour. In our series, the size of the tumour was not significantly related to the capability of CDS to depict intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow.

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, because we only included subjects who were referred for sonography after being diagnosed with hepatic haemangiomas with APS on CT and/or MRI and the sonographers were aware of the CT and/or MR findings of the tumours, the frequency of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow was almost certainly overestimated. Therefore, the frequency of such findings in routine clinical practice should be further verified by means of a blinded prospective study. Secondly, the performance of CDS may be operator dependent. In our study, all CDS examinations were performed by two board-certified abdominal radiologists with >5 years’ experience; two different radiologists with similar experience and perspectives on haemangioma and Doppler may have enabled a similar CDS performance. However, the general performance of CDS should be further evaluated. Thirdly, there is no histopathological verification of haemangiomas and no angiographic correlation of transtumoural APS. However, non-invasive imaging studies currently suffice for the diagnosis of hepatic haemangiomas and APS without referring to pathological or angiographic examination in most cases; angiographic or histopathological confirmation for the study is ethically unreasonable. Fourthly, we didn’t perform contrast-enhanced sonography, which may have enhanced the CDS results. However, use of contrast agents incurs additional cost, and this study shows that CDS, even without use of contrast agents, is commonly effective for demonstrating intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow in haemangiomas with APS.

In summary, CDS can commonly depict intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow in patients with hepatic haemangiomas with APS. Therefore, CDS should be routinely performed when an incidental mass is encountered during screening sonography, especially when the lesion is shallow, because identification of intratumoural flow and peritumoural hepatofugal portal flow may enhance the suspicion of hepatic haemangioma.

References

- 1.Perkins AB, Imam K, Smith WJ, Cronan JJ. Color and power Doppler sonography of liver hemangiomas: a dream unfulfilled? J Clin Ultrasound 2000;28:159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nino-Murcia M, Ralls PW, Jeffrey RB, Jr, Johnson M. Color Doppler flow imaging of focal hepatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:1195–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita Y, Ogata I, Urata J, Takahashi M. Cavernous hemangioma of the liver: pathologic correlation with dynamic CT findings. Radiology 1997;203:121–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanafusa K, Ohashi I, Himeno Y, Suzuki S, Shibuya H. Hepatic hemangioma: findings with two-phase CT. Radiology 1995;196:465–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim KW, Kim TK, Han JK, Kim AY, Lee HJ, Choi BI. Hepatic hemangiomas with arterioportal shunt: findings at two-phase CT. Radiology 2001;219:707–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naganuma H, Ishida H, Konno K, Hamashima Y, Komatsuda T, Ishida J, et al. Hepatic hemangioma with arterioportal shunts. Abdom Imaging 1999;24:42–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piekarski J, Goldberg HI, Royal SA, Axel L, Moss AA. Difference between liver and spleen CT numbers in the normal adult: its usefulness in predicting the presence of diffuse liver disease. Radiology 1980;137:727–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limanond P, Raman SS, Lassman C, Sayre J, Ghobrial RM, Busuttil RW, et al. Macrovesicular hepatic steatosis in living related liver donors: correlation between CT and histologic findings. Radiology 2004;230:276–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamer OW, Aguirre DA, Casola G, Lavine JE, Woenckhaus M, Sirlin CB. Fatty liver: imaging patterns and pitfalls. Radiographics 2006;26:1637–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka S, Kitamura T, Fujita M. Color Doppler flow imaging of liver tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;154:509–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golli M, Mathieu D, Anglade MC, Cherqui D, Vasile N, Rahmouni A. Focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: value of color Doppler US in association with MR imaging. Radiology 1993;187:113–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson NJ, Gibson RN. Hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia: colour Doppler ultrasound can be diagnostic. Australas Radiol 1995;39:296–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartolozzi C, Lencioni R, Paolicchi A, Moretti M, Armillotta N, Pinto F. Differentiation of hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: comparison of power Doppler imaging and conventional color Doppler sonography. Eur Radiol 1997;7:1410–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudo M. Imaging blood flow characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2002;Suppl 1:48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K, Numata K, Okazaki H, Nakamura S, Inoue S, Takamura Y. Diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: efficacy of color Doppler sonography compared with angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;160:1279–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruskal JB, Newman PA, Sammons LG, Kane RA. Optimizing Doppler and color flow US: application to hepatic sonography. Radiographics 2004;24:657–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strobel D, Krodel U, Martus P, Hahn EG, Becker D. Clinical evaluation of contrast-enhanced color Doppler sonography in the differential diagnosis of liver tumors. J Clin Ultrasound 2000;28:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KW, Kim AY, Kim TK, Kim SY, Kim MJ, Park MS, et al. Hepatic hemangiomas with arterioportal shunt: sonographic appearances with CT and MRI correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:W406–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]