Abstract

We describe the use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound as an additional imaging technique during an ultrasound examination of a traumatised testis, allowing for confident testicular preserving surgery to be performed.

Testicular trauma often arises as a consequence of a road traffic accident, a sporting mishap or a straddle injury. It tends to affect the younger male, in whom preservation of the testis is an important consideration. Clinical examination is difficult in the acute setting where establishment of the need for early surgical exploration is important and is notoriously inaccurate. Often greyscale ultrasound with the addition of colour Doppler techniques is the most useful investigation tool, readily identifying the appearance of testicular injury and so establishing the need for surgical exploration [1]. The appearances of testicular fracture, rupture, haematoma and haematocoele are readily identified on sonography, giving the surgeon a clear understanding of the status of the injury to the scrotal content and the need for exploration [2]. The establishment of continued blood flow to the injured testis has traditionally been based on the presence of colour Doppler signal; enabling the surgeon to tailor the surgery to either perform an orchidectomy or plan organ-sparing surgery. However, colour Doppler techniques have limitations; operator experience, movement artefact, patient discomfort and tissue reflectivity all play a part in diminishing the accuracy of the technique [3]. The use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is firmly established in many organs in the body, but less widely used in the testis [4]. CEUS is an ideal technique to ascertain the vascular supply to an organ, as the contrast agent is purely an intravascular agent and increases the sensitivity of detection of blood flow.

We describe the use of CEUS as a tool for precise assessment of viable testicular tissue post-scrotal trauma, allowing a rapid and precise delineation of viable testicular tissue enabling organ-sparing treatment in testicular trauma.

Case history

A 39-year-old male presented to the accident and emergency department following trauma to the right testis. The injury was sustained during a cricket match, when the patient collided with the wicket whilst fielding, not wearing any gonadal protection. There was no relevant medical or drug history and the patient was otherwise fit and well. On examination the right testis was swollen and tender, with difficulty in ascertaining the status of the contents of the scrotal sac. Observations were stable; blood biochemistry and haematology were unremarkable. An ultrasound examination was requested. An ultrasound examination was performed using a Siemens S2000 (Siemens, Mountain View, CA), with a linear array high frequency 9L4 transducer, with settings suitable for a scrotal examination. The left testis was unremarkable. The contour of superior pole of the right testis was ill-defined and suggestive of a tunica albuginea rupture, with several focal areas of hyporeflectivity and an associated small hydrocoele (Figure 1). Conventional colour Doppler examination demonstrated minimal vascular flow to the entire right testis, with the possibility of movement artefact contributing to the detection of colour signal (Figure 2). A CEUS was performed to further delineate the extent of vascular compromise to the right testis. Using the same transducer, employing a low mechanical index (MI) technique (Cadence Contrast Pulse sequencing, CPS™, Siemens, Mountain View, CA) and 4.8 ml of SonoVue™ (Bracco SpA, Milan, Italy), the right testis was examined in accordance with normal departmental protocol for a CEUS examination of the testis (Bolus of 4.8 ml of SonoVue™, followed by 10 ml of normal saline via an antecubital vein cannula, MI set at or below 0.10, split screen technology if needed, imaging recorded on cine loop for 90 s for later review). All images were stored on a picture archiving system (Centricity; GE Healthcare, Barrington, IL). Following contrast administration there was evidence of vascularisation of the lower aspect of the testis but absent flow to the previously noted areas of mixed reflectivity at the upper aspect of the testis (Figure 3). The CEUS technique identified clearly viable testicular tissue with a vascular supply, distinct from the non-enhanced non-vascularised testicular tissue compromised by the sustained trauma. This was discussed with the urologist and a decision was made based on the CEUS findings to perform urgent scrotal exploration with a view for testis sparing surgery. Surgery was performed via a scrotal approach in the standard manner, with a partial orchidectomy retaining the area of viable tissue seen on the CEUS examination (Figure 4a,b). Histology confirmed interstitial haemorrhage and tubular ischaemia due to external trauma. Post-surgery there were no immediate complications. 3 months later a repeat sonographic examination was performed, including CEUS, which identified normal vascular perfusion except for a small area of hypoperfusion at the superior-most aspect of the testis (Figure 5a,b). No further intervention was performed and the patient remains well.

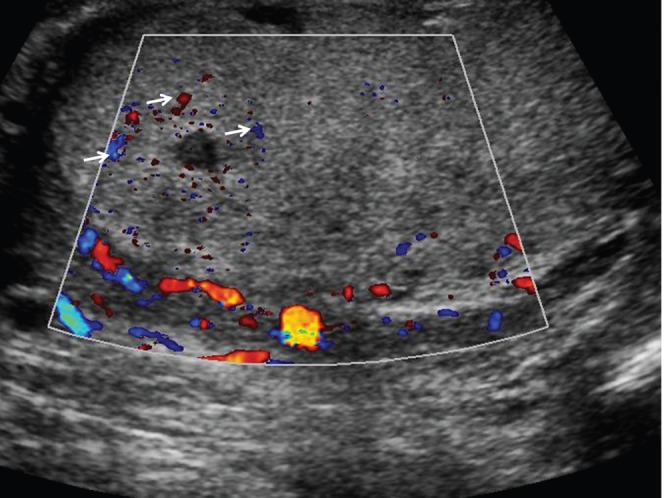

Figure 1.

Longitudinal image of the right testis, with an enlarged upper pole (star) and several areas of low reflectivity at the site of trauma (arrows).

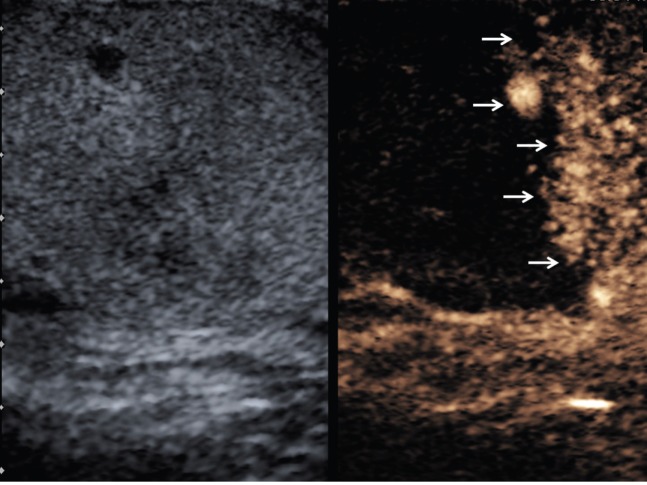

Figure 2.

Longitudinal image of the right testis, with colour Doppler mode, demonstrating a paucity of colour Doppler flow to the entire right testis, with pockets of colour signal (arrows); likely to be artefact.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal image of the right testis with microbubble contrast imaging, 24 s after administration of SonoVue™ (Bracco SpA, Milan, Italy), demonstrating a clear demarcation between vascularised and non-vascularised tissue (arrows).

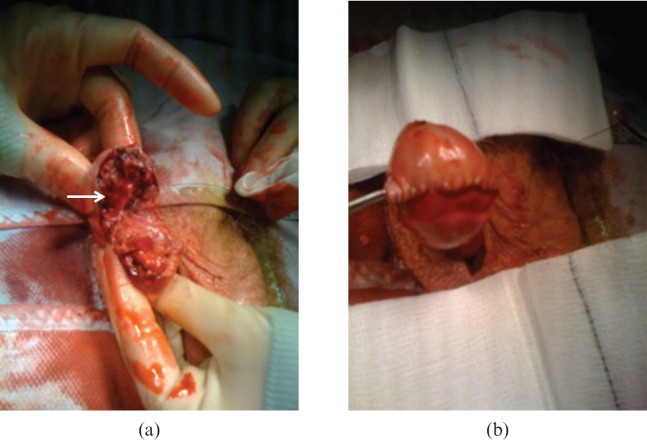

Figure 4.

(a) At surgical exploration, the tissue of the upper third of the testis (arrow) is “dusky” without demonstrable blood flow. This ischaemic area is excised with preservation of the remainder of the testis. (b) Following non-viable tissue excision, the testis is reconstructed and secured as shown.

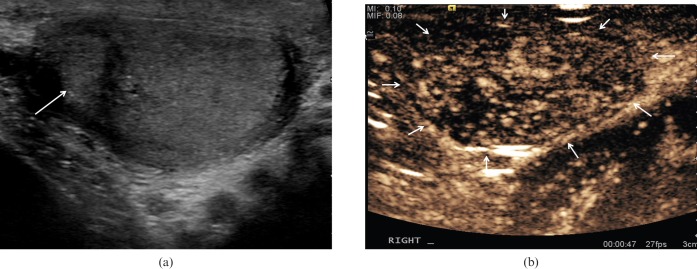

Figure 5.

(a) Longitudinal image of the right testis 3 months post-surgery demonstrating an area of altered reflectivity at the upper aspect of the testis (arrow). (b) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the right testis at 47 s after administration of SonoVue™ (Bracco SpA, Milan, Italy), demonstrating perfusion of the entire remaining right testis.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the utility of a new ultrasound technique, CEUS, in demonstrating with great clarity the extent of viable testicular tissue in a case of blunt scrotal trauma, which allowed for organ-sparing surgery and a satisfactory patient outcome.

The essential remit of ultrasound in the setting of blunt scrotal injury is to establish the need for operative intervention to salvage the testis or to indicate the need for an orchidectomy when there is no possibility of testicular viability. This distinction, although often well ascertained with conventional ultrasound techniques, may not always be attainable for a number of reasons. The cardinal features that are sought on a conventional ultrasound examination include; testicular rupture (loss of the normal appearance of the tunica albuginea, irregular testis margins) [5], fracture (an echo-poor linear or branching structure through the testicular parenchyma with heterogeneous areas) [2], intratesticular haematoma (focal high reflective area) [6] and avulsion (total absence of flow to a disrupted testis) [7]. In addition secondary findings in blunt testicular trauma may be seen on ultrasound; a haematocoele and epididymal disruption. Testicular rupture and vascular compromise are important diagnoses to make as early surgery has been shown to decrease the risk of necrosis and abscess formation post-operatively [8]. Furthermore, injuries involving the rete testis may result in devitalisation of the whole testis and any preservation of testicular tissue, as in the present case, is an important finding to aid surgical intervention [1,7]. Ultrasound has been shown to be highly sensitive in detecting testicular rupture; pre-operative scrotal colour Doppler ultrasound was compared with histological diagnosis in 298 boys who underwent surgery following testicular trauma demonstrating a sensitivity of 96.8% and a specificity of 97.9% for ultrasound [9]. The addition of CEUS will establish any tissue viability, an additional benefit from identifying the presence of trauma alone, and directing surgical intervention.

CEUS is firmly established in many spheres of imaging, and is particularly useful in the characterisation of focal liver lesions, cardiology and renal disease [10]. The microbubble agent used (SonoVue™) is entirely an intravascular agent and therefore does not “leak” into surrounding tissue, giving a true representation of the vascular supply to the area under observation, an important consideration when assessing tissue viability. The improvement in enhancement is 300-fold, coupled with the newer techniques of harmonic imaging and “pulse-inversion” techniques that will suppress normal tissue and enhance the returning echoes of the microbubble, resulting in a purely vascular perfusion image; an asset in the depiction of viable vascularised tissue. CEUS has also an established role in the assessment of solid organ injury in blunt abdominal trauma, where fractures, lacerations and haematomas are accurately demonstrated, with a sensitivity and specificity approaching that of contrast-enhanced CT imaging [11]. The extension of the use into the testis has been possible with the development of transducer technology, which enables microbubble visualisation at higher frequencies than previously [12]. The microbubble resonates best at 3 MHz coinciding with the largest number of microbubbles in the aliquot administered, and is the frequency normally applicable to abdominal and cardiac scanning. The use of higher frequency transducers, in this case 9 MHz, can make use of the microbubbles at the end of the “bell-shaped” curve of microbubble sizes, explaining the need for the higher dose of 4.8 ml (normal 1.2–2.4 ml). SonoVue™ has a product licence for vascular imaging and would therefore be an ideal product to use in the assessment of vascularised and therefore viable tissue in the context of testicular trauma.

CEUS has been used sparingly in the assessment of testicular abnormalities with few reports in the literature. Moschouris et al [13] examined a series of 19 patients with a painful scrotum, 6 of whom had a history of trauma, concluding that there was not a significant advantage over conventional colour Doppler ultrasound. However the assessment of perfusion and tissue viability was not an important goal of the study. Further evidence of the usefulness of CEUS in depicting areas of poor or absent perfusion is shown in a more recent study of the role of microbubble contrast in segmental testicular infarction, where all patients with this condition showed no or poor enhancement in the affected area following contrast administration [14]. Although the necessary expertise in performing a CEUS examination is limited to specialist centres at present, there is growing acceptance of CEUS as an essential technique.

This case has highlighted the role CEUS can offer in the imaging pathway of testicular trauma. It can aid in the accurate diagnosis of viable tissue post-trauma and assess the extent of non-viable tissue at initial presentation and follow-up. The fine vascular detail it provides is useful for tissue-sparing surgical planning in patients who would otherwise potentially have a complete orchidectomy and may even ultimately obviate the need for exploratory surgery if there is confidence in the establishment of normal vascularised tissue.

References

- 1.Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Use of ultrasound for the diagnosis of testicular injuries in blunt scrotal trauma. J Urol 2006;175:175–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbener TE. Ultrasound in the assessment of the acute scrotum. J Clin Ultrasound 1996;24:405–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen TD, Elder JS. Shortcomings of color Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of testicular torsion. J Urol 1995;154:1508–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson SR, Greenbaum LD, Goldberg BB. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound: what is the evidence and what are the obstacles? Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhandary P, Abbit PL, Watson L. Ultrasound diagnosis of traumatic testicular rupture. J Clin Ultrasound 1992;20:346–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purushothaman H, Sellars ME, Clarke JL, Sidhu PS. Intra-testicular haematoma: differentiation from tumour on clinical history and ultrasound appearances in two cases. Br J Radiol 2007;80:e184–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Diagnosis and management of testicular ruptures. Urol Clin North Am 2006;33:111–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffrey RB, Laing FC, Hricak H, McAninch JW. Sonography of testicular trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;141:993–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guichard G, El Ammari J, Del Coro C, Cellarier D, Loock PY, Chabannes E, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography in diagnosis of testicular rupture after blunt scrotal trauma. Urology 2008;71:52–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claudon M, Cosgrove D, Albrecht T, Bolondi L, Bosio M, Calliada F, et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) - Update 2008. Ultraschall in der Medizin 2008;29:28–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catalano O, Aiani L, Barozzi L, Bokor D, De Marchi A, Faletti C, et al. CEUS in abdominal trauma: multi-center study. Abdom Imaging 2009;34:225–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah A, Lung PF, Clarke JE, Sellars ME, Sidhu PS. New Ultrasound techniques for imaging of the indeterminate testicular lesion may avoid surgery completely. Clin Radiol 2010;65:496–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moschouris H, Stamatiou K, Lampropoulou E, Kalikis D, Matsaidonis D. Imaging of the acute scrotum; is there a place for contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Int Braz J Urol 2009;35:702–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertolotto M, Derchi LE, Sidhu PS, Valentino M. Acute segmental testicular infarction at contrast-enhanced ultrasound: early features and changes during follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;196:834–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]