Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate differences of diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) using a different number of diffusion-encoding directions and to evaluate the feasibility of tractography in healthy prostate at 3 T.

Method

12 healthy volunteers underwent DTI with single-shot echo-planar imaging at 3 T using a phased-array coil. Diffusion gradients of each DTI were applied in 6 (Group 1), 15 (Group 2) and 32 (Group 3) non-collinear directions. For each group, the mean apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), fractional anisotrophy (FA) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) were measured in the peripheral zone (PZ) and central gland (CG). The quality of diffusion-weighted and tractographic images were also evaluated.

Results

In all three groups, the mean ADC value of the CG was statistically lower than that of the PZ (p<0.01) and the mean FA value of the CG was statistically greater than that of the PZ (p<0.01). For the mean FA value of the CG, no statistical difference was seen among the three groups (p=0.052). However, the mean FA value of the PZ showed a statistical difference among the three groups (p=0.035). No significant difference in SNR values was seen among the three groups (p>0.05). Imaging quality of diffusion-weighted tractographic images was rated as satisfactory or better in all three groups and was similar among the three groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, prostate DTI at 3 T was feasible with different numbers of diffusion-encoding directions. The number of diffusion-encoding directions did not have a significant effect on imaging quality.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a common non-invasive method of assessing the anisotropy and organisation of structures in neurological and musculoskeletal imaging [1-4]. Generally, water diffusion in tissues without a well-organised microstructure shows isotropic direction whereas that in structures with a high degree of structural order has a preferential direction or anisotropy [5,6]. The prostate consists of histologically different components—glandular and fibromuscular elements. A few studies reported the potential of prostate tractography in evaluating the microstructural organisation of the prostate [7,8], but the role of tractography in the prostate has not been yet determined.

With the recent introduction of ultra-fast echo-planar sequences and parallel imaging techniques, DTI could be applied to the prostate [7-12]. Several studies have reported the results of DTI in a healthy prostate or prostate cancer at 1.5 T [9,11,12]. However, 1.5 T MR scanners have major limitations, such as poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which may affect the accuracy of measuring the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) or fractional anisotropy (FA) values. More recently, 3 T MR scanners have been introduced into clinical practice and DTI at 3 T has been a feasible tool in the prostate [7,8,10]. 3 T MR scanners have several benefits over 1.5 T MR scanners, such as a twofold increase in SNR, resulting in improved spatial and temporal resolution [13]. However, few studies have investigated the prostate DTI at 3 T [7,8,10].

The possible applications of DTI in prostate tissue investigated so far [7-12] have focused on differentiating between benign prostate tissue and cancer and determining normative FA and ADC values in the prostate. No studies for optimising DTI parameters such as number of diffusion-encoding directions in the prostate have been published, and there is no consensus for optimal diffusion-encoding directions in prostate DTI. To estimate the diffusion tensor, one needs diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) with high b-values along at least six non-collinear directions in addition to a low b-value DWI or a T2 weighted image (T2WI) (b=0) [5]. The rationale for sampling more directions is that this reduces the orientational dependence and increases the accuracy and precision of DTI parameters such as FA or mean diffusivity. However, more diffusion-encoding directions may need relatively longer imaging times and the amount of imaging time is limited in most clinical situations. The choice of optimal diffusion-encoding directions gives a trade-off between minimising directions bias and minimising scanning time.

Optimising image acquisition parameters is an essential step for producing high-quality DTI. Among several parameters, the number of diffusion-encoding gradient directions has been reported as one of several important factors for calculating DTI parameters, especially in neurological imaging [14,15]. In prostate DTI, 6 or 32 diffusion-encoding directions were applied in several previous studies to date [9,11,12]. To the best of our knowledge, there have as yet been no studies into the optimal numbers of diffusion-encoding directions for prostate DTI.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate differences of DTI using a different number of diffusion-encoding directions and to evaluate the feasibility of tractography in healthy prostates at 3 T.

Methods and materials

Study population

Between March 2009 and September 2009, a total of 13 healthy volunteers were enrolled in this prospective study. Each of the volunteers had no history of prostate disease. In one patient, there was a focal low signal nodule in the peripheral zone of the mid-gland at T2 weighted imaging and the patient was excluded from this study. Finally, 12 volunteers with a mean age of 32 years (range, 27–43 years) formed this study group. Informed consent was obtained from all volunteers and the protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

MRI protocol

All MRI examinations were performed with a 3 T scanner (Intera Achieva; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) using a six-channel phased-array [cardiac sensitivity encoding (SENSE)] coil (Philips Medical Systems). All volunteers underwent T2 weighted imaging and DTI. DTI was obtained with three different protocols: 6 (Group 1), 15 (Group 2) and 32 (Group 3) non-collinear directions of diffusion gradients.

Initially, T2 weighted turbo spin echo images [time of repetition (TR)/time of echo (TE) 3300–3800/100 ms; slice thickness 3 mm; interslice gap 1 mm; matrix 512×304; field of view (FOV) 20 cm; number of signals acquired (NSA) 3; SENSE factor 2] were obtained in the axial and sagittal planes. DTI with single-shot echo-planar imaging technique (TR/TE 4374/68 ms; slice thickness 3 mm; interslice gap 1 mm; matrix 112×110; NSA 2 in Group 1 and 2 and NSA 1 in Group 3; SENSE factor 2 in all groups; b-values 0 and 1000 s mm−2) was obtained in the axial plane. The acquisition times of DTI from Groups 1–3 were 2 min 54 s, 6 min 51 s and 7 min 17 s, respectively. Between T2 weighted imaging and DTI, slice thickness, interslice gap, FOV and slice location values were the same in order to maintain accurate zonal and anatomical correlation.

Data analysis

After data acquisition, all images were transferred to a workstation for analysis with manufacturer-supplied software (PRIDE; Philips Medical Systems). Qualitative analysis was performed by two subspecialised genito-urinary radiologists (BKP and CKK, with 8 and 6 years' experience and training in genito-urinary MRI, respectively) in consensus. Quantitative data analysis was performed by one genito-urinary radiologist (CKK).

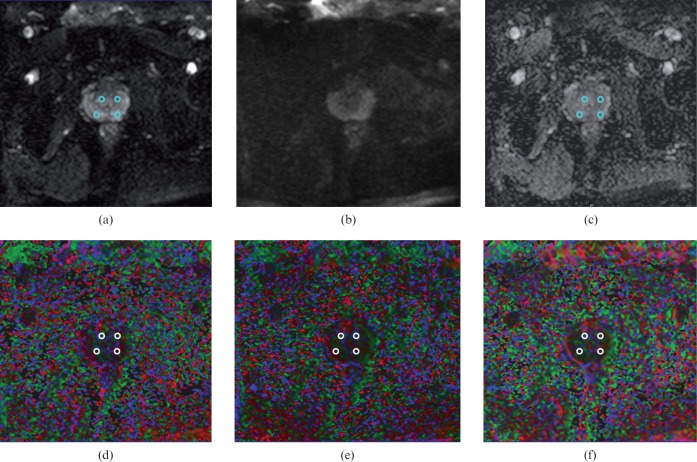

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed by regions of interest (ROIs) placement in all volunteers. ROIs were drawn on b=0 images using axial T2 weighted images as anatomical references and were then superimposed on ADC and FA maps of the three groups with different diffusion-encoding directions. On the largest axial image at the mid-gland level, ROIs were placed in the peripheral zone (PZ) and central gland (CG) on each side (Figure 1). The average of the PZ and CG values was recorded as the final value. The ROIs used were circular, measuring 30–40 pixels.

Figure 1.

Measurements of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anisotropy (FA) value in the peripheral zone and central gland of healthy prostate. Diffusion-weighted images of (a) b=0 and (b) 1000 s mm−2, (c) ADC and FA map with different diffusion-encoding directions (d–f) are well visualised without artefacts. Regions of interest are shown on (a, c) and colour-coded FA maps of 6 (d), 15 (e), and 32 (f) directions.

The SNR of the prostate on DWI was measured for each volunteer in the three groups: SNR=Sprostate/SDn where Sprostate is the mean signal intensity of the prostate and SDn is the standard deviation (SD) of the signal in the air outside the pelvis [16]. No noise filter during data acquisition was used. ROIs were defined by manually traced circular regions. A large ROI (>736 pixels) for signal intensity was placed within the outline of the prostate on an axial image at the mid-gland level. For noise, small ROIs (49 pixels) were placed in the background (air) at the corner of the same image. These measurements were repeated twice throughout DWI and the average value of SNR was calculated.

Qualitative analysis and tractography reconstruction

All diffusion-weighted images were visually inspected for the degree of overall imaging quality. The overall imaging quality of all diffusion-weighted images with respect to the visualisation of the PZ and CG, differentiation between prostate and adjacent structures or susceptibility artefacts was rated as excellent, good, satisfactory, poor and inadequate.

Tractography was performed using manufacturer-supplied software which was based on the fibre assignment by continuous tracking method [17,18]. Three ROIs were manually traced on DWI of b=0 in the outline of the prostate, at the level of the apex and mid-gland, and the region between the base and seminal vesicle. The reconstructions were focused on the main and well-known prostate “functional pathways” on the central gland. The represented fibres were superimposed on DWI of b=0 and T2 weighted imaging with blue, red and green colours representing craniocaudal, right–left and anteroposterior orientations, respectively. The average time required for processing the diffusion tensor data was approximately 10 min.

Qualitative analysis for tractographic images was performed in terms of orientation of prostate fibres, numbers of fibre structures and length of fibre bundles. The degree of imaging quality in the fibre tractographic images was compared among the three groups.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative measurements were reported as mean ±SD. The significance of the difference in ADC and FA values of the CGs and PZs among the three groups was determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test and Friedman'S test with Bonferroni correction. The significance of the difference in SNRs of the prostates at the three groups was determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test. For qualitative analysis of DWI and tractographic images in the three groups, descriptive data analysis was used owing to the small sample size. SPSS v. 17.0 statistics software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to perform all statistical calculations. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Quantitative analysis

The SNRs were 30.6±9.1 in Group 1, 29.5±9.9 in Group 2 and 29.8±9.8 in Group 3. There was no significant difference in SNR values among the three groups (p=0.717).

Table 1 presents the results of ADC and FA values in the PZ and CG of healthy prostates among the three groups with different diffusion-encoding directions. In all three groups, the mean ADC value of the CG was statistically lower than that of the PZ (p<0.01) and the mean FA value of the CG was statistically greater than that of the PZ (p<0.01). For the mean ADC among the three groups, no statistical difference was seen in the PZ and CG. For the mean FA value in the CG among the three groups, no statistical difference was seen (p=0.052). However, the FA value of the PZ showed a statistical difference between Group 1 and Groups 2 and 3 (p=0.035).

Table 1. Results of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anistopy (FA) values in peripheral zone and central gland of healthy prostate among three groups with different diffusion-encoding directions.

| Location | Quantitative parameter | Group 1(6 directions) | Group 2(15 directions) | Group 3(32 directions) |

| Peripheral zone | FA | 0.21±0.04 | 0.15±0.03 | 0.14±0.02 |

| ADC(−3 mm2 s−1) | 1.46±0.23 | 1.49±0.23 | 1.48±0.22 | |

| Central gland | FA | 0.34±0.07 | 0.26±0.05 | 0.28±0.05 |

| ADC(−3 mm2 s−1) | 1.27±0.09 | 1.25±0.08 | 1.27±0.10 |

Note: values are mean±standard deviation.

Qualitative analysis

For the degree of overall imaging quality on DWI, Group 1 had excellent (n=5) and good (n=7), Group 2 had excellent (n=4), good (n=7) and satisfactory (n=1), and Group 3 had excellent (n=3), good (n=8) and satisfactory (n=1).

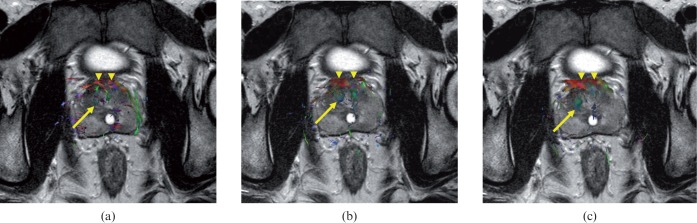

On tractography, the CG showed craniocaudal, anteroposterior or right–left orientation in all three groups. The anterior fibromuscular stroma demonstrated right–left orientation in all three groups for all volunteers. However, the PZ revealed no detectable fibre structures or some foci of anteroposterior orientation for all three groups. For the imaging quality in the three groups, the PZ was similar in all volunteers. The CG was similar in five volunteers. The remaining seven volunteers showed that Group 3 was equal to Group 2 and both Groups 2 and 3 were slightly superior to Group 1. The anterior fibromuscular stroma was similar in all groups. Thus, the overall imaging quality of tractography in the three groups was determined to be similar (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of fibre tractographic images of healthy prostate with (a) 6, (b) 15 and (c) 32 diffusion-encoding directions. In (a), several fine fibre structures in bilateral peripheral zones are seen, but no fibre structures in bilateral peripheral zones are seen in (b) and (c). In all images, the central gland reveals the green colour (arrow). For the numbers and lengths of fibre bundles in the central gland, there seems to be subtle difference among (a–c), but the overall imaging quality for fibre tractography seems to be similar. Note the anterior fibromuscular stroma showing the red colour (arrowheads).

Discussion

Our study indicates that FA values are significantly different between the PZ and CG, which may reflect a difference in microstructural organisation within the gland. Also, although FA values in the CG did not show a significant difference with number of diffusion directions, FA values in the PZ were significantly higher with a lower number of diffusion directions, which may reflect an error of DTI parameter calculation. In DTI, FA is a quantitative index of DWI used to characterise the degree of tissue anisotropy. The SNR in DTI can be affected by several factors such as the number of signal intensity averaging, diffusion-encoding directions and encoding levels [19]. Low SNR may result in variance of each of the tensor elements and finally in overestimating FA value. Smaller diffusion-encoding directions may introduce directional biases and reduced directional precision while larger diffusion-encoding directions can introduce more robust tensor ellipsoid estimation [14,20,21]. In our study, the three groups (6, 15 and 32 directions) showed similar SNR values in quantitative analysis. The results of FA values in the PZ and CG of our study using 32 diffusion-encoding directions were similar to those of a recent study [7] using 32 diffusion-encoding directions, indicating that up to 32 diffusion-encoding directions can be used confidently.

For normative ADC values in the prostate, several published data at 3 T show variable results in the PZ and CG [8,10,22,23]. The possible reason of these conflicts is that ADC may be influenced by T2, signal intensity on DWI, b factor, spin density and TE [5]. The number of diffusion-encoding directions is not a factor in influencing ADC value; this was reflected in our results where the mean ADC value in the PZ and CG among three groups with different diffusion-encoding directions showed no statistical differences.

In a healthy prostate, the CG enlarges with age and the PZ is often a thin rim of tissue [24,25]. It is these older patients that require prostate MRI for the detection and staging of prostate cancer. It may well be difficult to obtain FA values from these small compressed PZs where DTI would not be useful diagnostically. In our study, we did not analyse the changes of age-related FA or ADC values because all volunteers were aged 20–30 years, except one who was 43 years old.

A few investigations have assessed tractography using prostate DTI data [7,8]. The prostate is composed of approximately 70% glandular elements and 30% fibromuscular stroma. The stroma of the gland is mainly composed of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue. The CG consists of compact and organised smooth muscle fibres which may develop more restriction against the diffusivity of water molecules in certain directions, leading toanisotropy. However, the PZ has a relatively loose microstructural organisation which exhibits less restriction of water diffusion than the CG. In our study, the PZ demonstrated no detectable fibre structures or some foci of anteroposterior direction and anterior fibromuscular stroma revealed right–left direction. The CG showed various directions of fibre structures. These findings may reflect higher FA values in the CG compared with the PZ and are in concordance with the microstructural organisation of the PZ and CG. For the evaluation of imaging quality in tractography, although the degree of imaging quality in the CG of healthy prostate was slightly superior on 15 or 32 directions to that on 6 directions in 7 out of 12 patients, the overall imaging quality was similar among the three groups.

In this study, we used 3 different directions of diffusion-encoding gradients (6, 15 and 32 directions) in order to evaluate the degree of imaging quality in tractography of healthy prostate. Although the degree of imaging quality of tractography in the CG of healthy prostate was slightly superior on 15 or 32 directions to that on 6 directions in 7 out of 12 cases, the overall imaging quality of tractography was similar among the three groups. Considering scanning time and the degree of imaging quality of DTI, we believe that six directions may be sufficient to evaluate prostate pathologies within the prostate. However, larger studies are required to confirm this.

This study has several limitations. First, only a limited number of subjects were enrolled into this preliminary study. A larger number should be enrolled in a future study. Second, we did not evaluate the optimisation of other parameters such as b-values or geometric configuration of diffusion-encoding directions. Third, we evaluated only the healthy prostate at DTI. In future studies, the evaluation of prostate pathologies such as prostate cancer or prostatitis should be undertaken. Finally, we did not measure FA or ADC values in the whole prostate which might affect the results. In healthy prostate, the size of the prostate is small and thus the measurement of FA or ADC values in the PZ and CG in the base or apex might have increased errors between adjacent structures.

In conclusion, our preliminary study suggests that prostate DTI at 3 T is feasible in different numbers of diffusion-encoding directions. The number of diffusion-encoding directions did not have a significant effect on imaging quality of prostate DTI.

References

- 1.Mukherjee P. Diffusion tensor imaging and fiber tractography in acute stroke. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2005;15:655–65, xii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaraiskaya T, Kumbhare D, Noseworthy MD. Diffusion tensor imaging in evaluation of human skeletal muscle injury. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;24:402–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang S, Kim S, Chawla S, Zhang WG, O'Rourke DM, Judy KD, et al. Differentiation between glioblastomas and solitary brain metastases using diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 2009;44:653–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maier SE. Examination of spinal cord tissue architecture with magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. Neurotherapeutics 2007;4:453–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee P, Berman JI, Chung SW, Hess CP, Henry RG. Diffusion tensor MR imaging and fiber tractography: theoretic underpinnings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:632–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Q, Welsh RC, Chenevert TL, Carlos RC, Maly-Sundgren P, Gomez-Hassan DM, et al. Clinical applications of diffusion tensor imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2004;19:6–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurses B, Kabakci N, Kovanlikaya A, Firat Z, Bayram A, Uluğ AM, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the normal prostate at 3 tesla. Eur Radiol 2008;18:716–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manenti G, Carlani M, Mancino S, Colangelo V, Di Roma M, Squillaci E, et al. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging of prostate cancer. Invest Radiol 2007;42:412–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayama Y, Kishimoto R, Hanaoka S, Nonaka H, Kandatsu S, Tsuji H, et al. ADC value and diffusion tensor imaging of prostate cancer: changes in carbon-ion radiotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;27:1331–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbs P, Pickles MD, Turnbull LW. Diffusion imaging of the prostate at 3.0 tesla. Invest Radiol 2006;41:185–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimofusa R, Fujimoto H, Akamata H, Motoori K, Yamamoto S, Ueda T, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of prostate cancer. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005;29:149–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha S, Sinha U. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging of the human prostate. Magn Reson Med 2004;52:530–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim CK, Park BK. Update of prostate magnetic resonance imaging at 3 T. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2008;32:163–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones DK. The effect of gradient sampling schemes on measures derived from diffusion tensor MRI: a Monte Carlo study. Magn Reson Med 2004;51:807–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee P, Chung SW, Berman JI, Hess CP, Henry RG. Diffusion tensor MR imaging and fiber tractography: technical considerations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:843–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietrich O, Raya JG, Reeder SB, Reiser MF, Schoenberg SO. Measurement of signal-to-noise ratios in MR images: influence of multichannel coils, parallel imaging, and reconstruction filters. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;26:375–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori S, Crain BJ, Chacko VP, van Zijl PC. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 1999;45:265–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SK, Kim DI, Kim J, Kim DJ, Kim HD, Kim DS, et al. Diffusion-tensor MR imaging and fiber tractography: a new method of describing aberrant fiber connections in developmental CNS anomalies. Radiographics 2005;25:53–65; discussion 66–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B, Hsu EW. Noise removal in magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med 2005;54:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadakis NG, Xing D, Huang CL, Hall LD, Carpenter TA. A comparative study of acquisition schemes for diffusion tensor imaging using MRI. J Magn Reson 1999;137:67–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasan KM, Parker DL, Alexander AL. Comparison of gradient encoding schemes for diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;13:769–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim CK, Park BK, Lee HM, Kwon GY. Value of diffusion-weighted imaging for the prediction of prostate cancer location at 3 T using a phased-array coil: preliminary results. Invest Radiol 2007;42:842–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickles MD, Gibbs P, Sreenivas M, Turnbull LW. Diffusion-weighted imaging of normal and malignant prostate tissue at 3.0 T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;23:130–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen KS, Kressel HY, Arger PH, Pollack HM. Age-related changes of the prostate: evaluation by MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1989;152:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamada T, Sone T, Toshimitsu S, Imai S, Jo Y, Yoshida K, et al. Age-related and zonal anatomical changes of apparent diffusion coefficient values in normal human prostatic tissues. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;27:552–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]