Abstract

Objective

Medical diagnostic procedures can be considered the main man-made source of ionising radiation exposure for the population. Conventional radiography still represents the largest contribution to examination frequency. The present work evaluates procedure frequency and effective dose from the majority of conventional radiology examinations performed at the Radiological Department of Aosta Hospital from 2002 to 2009.

Method

Effective dose to the patient was evaluated by means of the software PCXMC. Data provided by the radiological information system allowed us to obtain collective effective and per caput dose.

Results

The biggest contributors to per caput effective dose from conventional radiology are vertebral column, abdomen, chest, pelvis and (limited to females) breast. Vertebral column, pelvis and breast procedures show a significant dose increment in the period of the study. The mean effective dose per inhabitant from conventional radiology increased from 0.131 mSv in 2002 to 0.156 mSv in 2009. Combining these figures with those from our study of effective dose from CT (0.55 mSv in 2002 to 1.03 mSv in 2009), the total mean effective dose per inhabitant increased from 0.68 mSv to 1.19 mSv. The contribution of CT increased from 81% to 87% of the total. In contrast, conventional radiology accounts for 85% of the total number of procedures, but only 13% of the effective dose.

Conclusion

The study has demonstrated that conventional radiography still represents the biggest contributor to examination frequency in Aosta Valley in 2009. However, the frequency of the main procedures did not change significantly between 2002 and 2009.

Radiation exposure by medical diagnostic procedures can be considered the main man-made source of ionising radiation exposure for the population. Conventional radiography still represents the largest contributor to examination frequency, despite the proliferation of other modalities, such as CT and MRI. As the report of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) concluded in 2000 [1], the radiation dose to patients undergoing conventional radiological procedures may range from 0.1 to 10 mSv. Furthermore, patient dose may vary between hospitals (or even in different facilities in the same hospital) by a factor of between 2 and 20, as reported by various national surveys [2,3].

Despite these concerns, the radiation dose levels to patients in conventional radiography are generally negligible if compared with the benefits derived from these procedures, and there are few data published in recent years on population dose from conventional radiology. Most of the published data deal with the years 1990–2004 [4-7]. Dosimetric evaluations are generally limited to the main standard procedures, such as chest, head and abdomen, and the effective dose is calculated using the diagnostic reference levels as input dose value. Moreover, few data are available from Italian radiology departments [8].

With an area of just 3300 km2, Aosta Valley is the smallest, least populous and least densely populated region in north-western Italy, with about 125 000 inhabitants and a unique public health structure, consisting of a major hospital, a secondary hospital and eight health centres. For its demographic and socioeconomics characteristics, the Valle d'Aosta region can be considered representative of the level I countries (with at least one physician per 1000 population, as defined by UNSCEAR [1]).

In a previous study we have investigated CT examination frequency and collective effective dose in the Aosta Valley between 2001 and 2008 [9]. The aim of the present work is to complete our earlier findings by evaluating the procedure frequency and the effective dose from most of the conventional radiology examinations performed at our radiological department from 2002 to 2009, in order to better estimate the population collective effective dose from medical procedures.

Methods and materials

The data used in this study were collected from the conventional radiological units operating at the radiological department of the Aosta Hospital between 2002 and 2009: one digital radiography (DR) and two computed radiography (CR) general purpose radiography units; one DR and one CR chest unit; one fluoroscope for uroradiology and gastrointestinal examinations; two full-field mammography systems; two DR panoramic and cephalometric systems; and two mobile radiography units. Departmental operations are managed by an automated radiology information system (RIS) with functions that include scheduling, patient and film folder tracking, transcription and electronic report approval. The RIS is connected to the hospital information system (HIS), which offers order entry and reporting capabilities. The department is filmless, with Siemens picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

Patient effective dose was evaluated by computer simulation using PCXMC (v. 2.0), a program developed by STUK Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (Helsinki, Finland) for calculating patients' organ doses and effective dose in medical radiographic examinations. The program uses a Monte Carlo engine to evaluate the delivered effective dose E to a more sophisticated version of the mathematical hermaphrodite phantom model of Cristy and Eckerman [10], representing patients of six different age groups, from newborn to adult.

Effective dose calculation can be performed using the tissue weighting factors (WT) reported by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Publication 103 [11]:

|

The software's tissue data include active bone marrow, adrenals, brain, breast, colon (upper and lower large intestine), gall bladder, heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, muscle, oesophagus, ovaries, pancreas, skeleton, skin, small intestine, spleen, stomach, testes, thymus, thyroid, urinary bladder and uterus.

PCXMC calculates the patient's organ dose starting from the acquisition parameters (tube potential, filtration, focus skin distance, geometry of the X-ray beam) and the incident air kerma Ka, supplied by the user, representing the air kerma at the point where the central axis of the X-ray beam enters the patient [12]. The amount of radiation can also be inserted as the entrance exposure, air kerma–area product, dose–area product or exposure–area product. Ka can be calculated starting from the X-ray source output measurements for each set of examination exposure parameters. Alternatively, Ka can be obtained from entrance surface air kerma measurements or starting from patient examination dose–area product measurements. If these measurements are not available, the program can estimate Ka with a reasonable accuracy from the X-ray tube current–time product, starting from the knowledge of tube potential, filtration and focus–skin distance supplied by the user. We estimate effective doses using air kerma measurements as software input.

The acquisition parameters and the measured incident air kerma of the radiological procedures considered in the study are reported in Tables 1 and 2 for both child and adult patients, respectively. For those procedures involving the use of the current automatic control, the acquisition parameters have been obtained by a statistical analysis of the examination data performed in the last year of the study and registered in the radiological information system (RIS). The listed protocols represent 95% of the conventional radiography performed at the radiological department of the Aosta Hospital. They have been optimised and implemented on the appropriate radiological systems by radiologists and physicists during the commissioning procedure, and it can be assumed that they have remained unchanged over the period of the study.

Table 1. Child acquisition protocols.

| Exam type | Protocol | Projection | Tube potential (kV) | Filtration (mm Al) | FSD (cm) | Width (cm at FSD) | Height (cm at FSD) | Incident air kerma (mGy) |

| Abdomen | Abdomen | PA | 80 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 25 | 0.16 |

| AP | 80 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 25 | 0.16 | ||

| Extremity | Extremities | LAT | 65 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 15 | 0.11 |

| AP | 65 | 2.5 | 150 | 20 | 20 | 0.11 | ||

| Shoulder | AP | 65 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 15 | 0.11 | |

| Pelvis | Pelvic girdle | AP | 75 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 15 | 0.28 |

| Hip-femoral | AP | 75 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 10 | 0.28 | |

| Vertebral column | Cervical | LAT | 70 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 15 | 0.5 |

| AP | 75 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 15 | 0.29 | ||

| Dorsal | LAT | 85 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 25 | 0.37 | |

| AP | 80 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 25 | 0.27 | ||

| Lumbar-sacral | LAT | 90 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 20 | 0.22 | |

| AP | 85 | 2.5 | 150 | 10 | 20 | 0.13 | ||

| Head | Cranial | LAT | 80 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 20 | 0.07–0.67 |

| PA | 80 | 2.5 | 100 | 15 | 20 | 0.08–0.52 | ||

| Dental | Dental | AP | 66 | 2.5 | 50 | 15 | 10 | 157.85a |

| Chest | Thorax | PA | 110 | 2.5 | 180 | 25 | 20 | 0.045 |

| Ribs | AP | 110 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 25 | 0.04 | |

| OBL | 110 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 25 | 0.04 |

AP, anteroposterior; FSD, focus–skin distance; LAT, lateral; OBL, oblique; PA, postero-anterior.

aDose area product (mGy cm2).

Table 2. Adult acquisition protocols.

| Exam type | Protocol | Projection | Tube potential (kV) | Filtration (mm Al) | FSD (cm) | Width (cm at FSD) | Height (cm at FSD) | Incident air kerma (mGy) |

| Abdomen | Abdomen | PA | 75 | 2.5 | 150 | 40 | 45 | 0.66–2.4 |

| AP | 85 | 2.5 | 180 | 40 | 45 | 0.66–2.40 | ||

| Cystography | LAT | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 1.0 | |

| OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 3.3 | ||

| AP | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 2.5 | ||

| OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 25 | 25 | 1.5 | ||

| Enema | LAT | 85 | 2.5 | 100 | 30 | 55 | 5.0 | |

| PA | 85 | 2.5 | 100 | 40 | 55 | 3.6 | ||

| OBL | 85 | 2.5 | 100 | 25 | 20 | 5.0 | ||

| AP | 85 | 2.5 | 100 | 40 | 45 | 2.1 | ||

| OBL | 85 | 2.5 | 100 | 30 | 35 | 5.0 | ||

| Digestive | LAT | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 55 | 4.0 | |

| OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 40 | 2.0 | ||

| AP | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 55 | 3.77 | ||

| OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 40 | 2.25 | ||

| Pelvis | Pelvis girdle | AP | 75–85 | 2.5 | 100 | 50 | 40 | 1.18–6 |

| Hip-femoral | AP | 70–75 | 2.5 | 100–150 | 30 | 60 | 1.75–3 | |

| Extremity | Extremities | LAT | 55 | 3 | 100–150 | 25 | 25 | 0.1–1.33 |

| AP | 70 | 2.5 | 100–150 | 20 | 20 | 0.1–1.16 | ||

| Shoulder | AP | 60 | 2.5 | 100 | 20 | 50 | 0.22–1.04 | |

| Vertebral column | Cervical | LAT | 65 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 20 | 0.51–2.5 |

| AP | 80 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 20 | 0.44–2.6 | ||

| Dorsal | LAT | 80–90 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 40 | 0.69–6.5 | |

| AP | 75–80 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 40 | 1.23–5.6 | ||

| Lumbar-sacral | LAT | 75 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 40 | 2.2–10.21 | |

| AP | 90 | 2.5 | 150 | 15 | 40 | 1.73–6.38 | ||

| Full spine | LAT | 96 | 2.5 | 180 | 20 | 80 | 0.97–2.9 | |

| AP | 81 | 2.5 | 180 | 20 | 80 | 0.96–4.60 | ||

| Head | Cranial | LAT | 70 | 2.5 | 100 | 15 | 20 | 0.37–2.17 |

| PA | 70 | 2.5 | 100 | 15 | 20 | 0.59–3.1 | ||

| Dental | Dental | AP | 71 | 2.5 | 50 | 20 | 10 | 163.2a |

| Chest | Thorax | LAT | 108 | 2.5 | 180 | 40 | 40 | 0.17–1.04 |

| PA | 120 | 2.5 | 180 | 40 | 40 | 0.05–0.42 | ||

| Ribs | OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 40 | 0.37–3.58 | |

| AP | 77 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 40 | 0.37–2.66 | ||

| OBL | 77 | 2.5 | 150 | 25 | 40 | 0.37–3.58 | ||

| Breast | Mammography | AP | 40 | 50μm R | 60 | 18 | 24 | 6.8b |

AP, anteroposterior; FSD, focus–skin distance; LAT, lateral; OBL, oblique; PA, postero-anterior.

aDose–area product (mGy cm2).

bEntrance surface air kerma.

Data provided by the RA2000 radiological information system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Concord, CA) working at the radiological department allowed us to obtain the number and type of conventional radiological exams performed from 2002 to 2009 as a function of patient's age and sex.

First we calculated the collected effective dose (CED) from diagnostic radiological examinations, in units of man Sv, according to the formula

|

(2) |

where Ei represents the mean effective dose to patients from a particular examination type obtained by the PCXMC software and Ni is the corresponding number of procedures performed each year. Then, the per caput dose was obtained by dividing the collective dose by the number of inhabitants. Finally, the number of exams for 100 000 inhabitants has been evaluated using the data provided by the Aosta Valley OREPS (Osservatorio Regionale Epidemiologico per le Politiche Sociali) for the study period, and stratified by sex and age.

Results

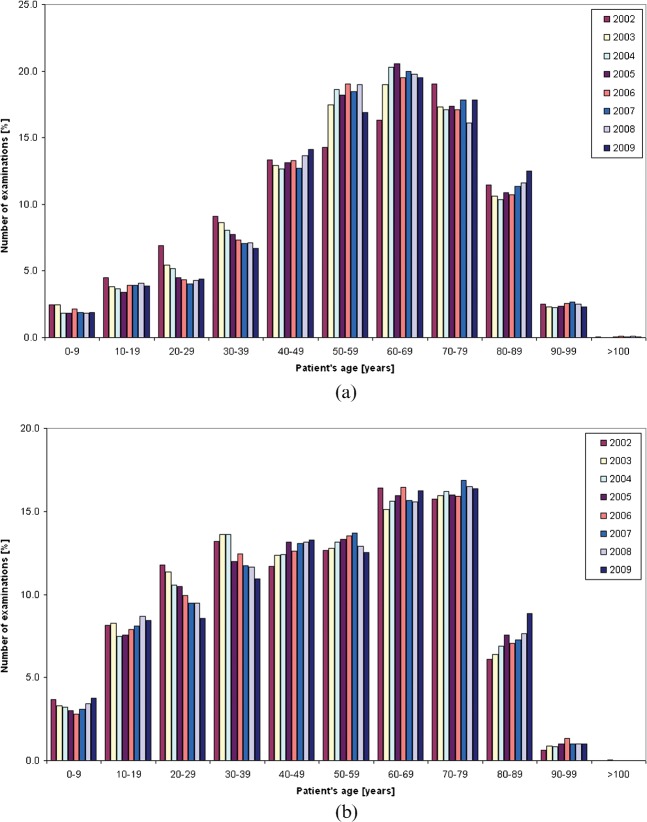

The total number of exams per 100 000 inhabitants, subdivided for sex and age, is reported in Table 3. The percentage distribution of conventional radiologic procedures by patient's age is reported in Figure 1a,b for females and males, respectively; as shown, the number of exams performed on patients older than 60 years is greater for females (50% vs 40% for males). Figure 2 shows the total percentage distribution of the main examination types during the study time.

Table 3. Number of examinations per 100 000 inhabitants, 2002–9, subdivided by age and sex.

| Age | Sex | Number of examinations per 100 000 inhabitants |

|||||||

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | ||

| All | Female | 27 433 | 31 649 | 34 533 | 34 828 | 37 309 | 35 976 | 37 995 | 38 960 |

| Male | 27 722 | 27 485 | 28 057 | 27 750 | 29 070 | 28 514 | 29 945 | 29 958 | |

| <10 years | Female | 676 | 773 | 635 | 632 | 791 | 676 | 688 | 739 |

| Male | 1023 | 910 | 899 | 831 | 819 | 881 | 1027 | 1126 | |

| ≥10, <20 | Female | 1239 | 1205 | 1266 | 1182 | 1463 | 1418 | 1549 | 1509 |

| Male | 2252 | 2274 | 2100 | 2093 | 2290 | 2309 | 2603 | 2525 | |

| ≥20, <30 | Female | 1896 | 1717 | 1795 | 1560 | 1627 | 1449 | 1628 | 1703 |

| Male | 3264 | 3120 | 2958 | 2909 | 2892 | 2708 | 2839 | 2560 | |

| ≥30, <40 | Female | 2497 | 2739 | 2783 | 2692 | 2727 | 2540 | 2708 | 2601 |

| Male | 3657 | 3746 | 3824 | 3329 | 3623 | 3347 | 3484 | 3275 | |

| ≥40, <50 | Female | 3658 | 4092 | 4363 | 4575 | 4955 | 4581 | 5191 | 5494 |

| Male | 3239 | 3395 | 3480 | 3645 | 3666 | 3726 | 3941 | 3984 | |

| ≥50, <60 | Female | 3921 | 5533 | 6427 | 6333 | 7095 | 6646 | 7209 | 6586 |

| Male | 3505 | 3506 | 3685 | 3696 | 3936 | 3909 | 3869 | 3754 | |

| ≥60, <70 | Female | 4471 | 6008 | 7005 | 7165 | 7281 | 7192 | 7521 | 7593 |

| Male | 4552 | 4152 | 4385 | 4429 | 4783 | 4464 | 4664 | 4863 | |

| ≥70 year | Female | 9325 | 9085 | 9581 | 10 259 | 10 689 | 11 369 | 11 473 | 11 500 |

| Male | 5794 | 6231 | 6382 | 6725 | 6818 | 7061 | 7169 | 7518 | |

Figure 1.

Analysis by patients' age of the number of conventional radiology examinations performed on (a) females and (b) males between 2002 and 2009 at the Radiological Department of Aosta Hospital.

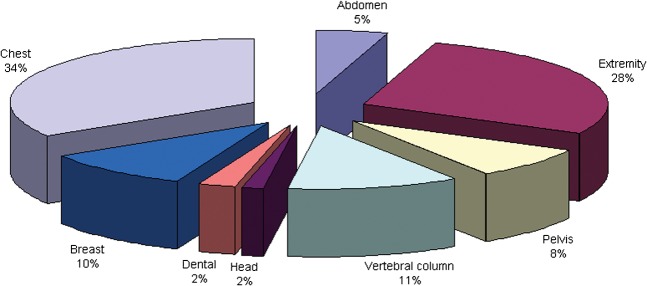

Figure 2.

Frequency of the main examination types performed between 2002 and 2009 at the Radiological Department of Aosta Hospital as a percentage of total procedures.

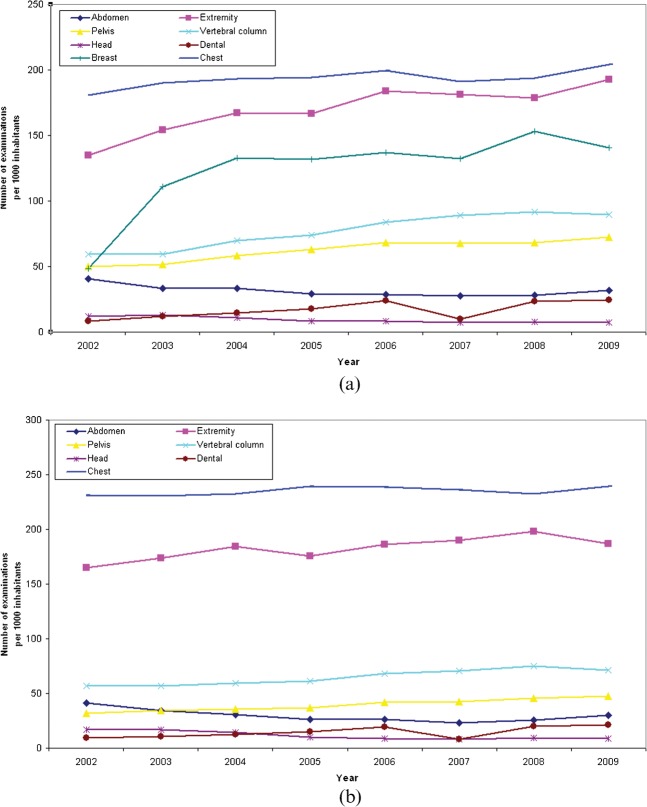

The contribution of the different types of examination is shown in Figure 3a,b, where the trend of the total number of exams per 1000 inhabitants in the years of the study is illustrated for female and male patients, respectively. We found a decrease in the frequency of abdomen and head examinations for both male patients (30% and 50%, respectively) and female patients (20% and 40%, respectively). The remaining procedures show an increase of between 13% for chest and 190% for dental and breast procedures for female patients, and between 4% and 135% for chest and dental procedures for male patients.

Figure 3.

Trend in the radiological examination frequency per 1000 inhabitants in Aosta Valley between 2002 and 2009 for females (a) and males (b).

The effective dose calculated by the PCXMC software for standard adult patients and children, using the ICRP 103 weighting factors, is reported in Table 4 for the main procedures implemented in our diagnostic facilities.

Table 4. Effective dose (mSv) evaluated for the main conventional radiology examinations for the standard adult man and child.

| Exam type | Exams (protocols) list | Adult (mSv) | Child (mSv) |

| Abdomen | Abdomen | 0.250–0.908 | 0.080 |

| Cystography | 0.623 | – | |

| Enema | 3.046 | – | |

| Digestive | 2.312 | – | |

| Pelvis | Pelvic girdle | 0.315–1.451 | 0.036 |

| Hip-femoral | 0.255–0.425 | 0.024 | |

| Extremity | Extremities | 0.005–0.061 | 0.001 |

| Shoulder | 0.054–0.304 | 0.010 | |

| Vertebral Column | Cervical | 0.046–0.244 | 0.045 |

| Dorsal | 0.191–1.163 | 0.091 | |

| Lumbar-sacral | 0.440–2.42 | 0.049 | |

| Full spine | 0.753–2.665 | – | |

| Head | Cranium | 0.002–0.116 | 0.01–0.040 |

| Dental | Dental | 0.009 | 0.022 |

| Breast | Mammography | 0.260 | – |

| Chest | Thorax | 0.047–0.299 | 0.011 |

| Ribs | 0.220–1.891 | 0.037 |

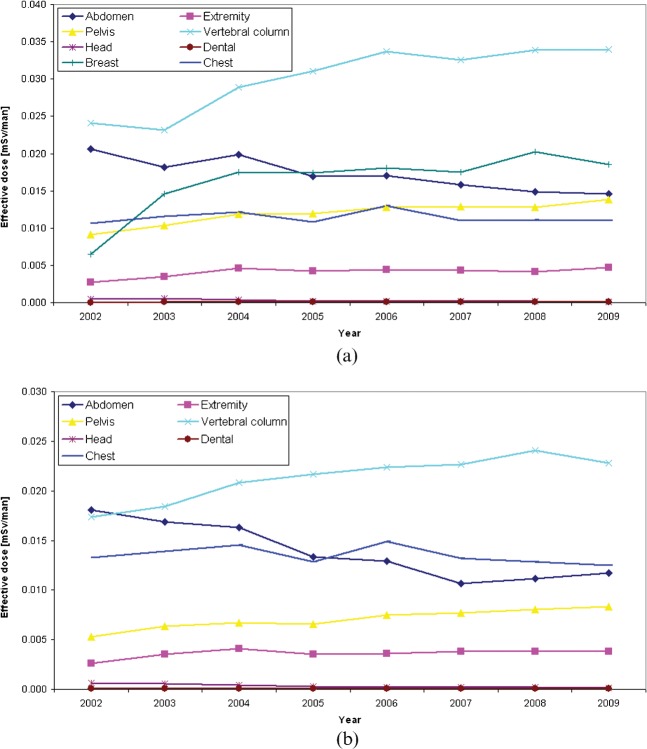

Figure 4 shows the trend of per caput effective dose for the examinations considered in our study, while the contributions from conventional radiology and CT procedures to the per caput effective dose are illustrated in Table 5 as a function of patients' age and sex. CT values are derived from our previous paper [9], updated to 2009 data.

Figure 4.

Analysis by examination type of the effective per caput dose to females (a) and males (b) between 2002 and 2009 in Aosta Valley.

Table 5. Per caput effective dose (mSv) evaluated for each year, sex and age group of the population.

| Age | Sex | Exam type | |||||||||

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | ||||

| All population | Conventional | 0.131 | 0.142 | 0.158 | 0.151 | 0.161 | 0.153 | 0.158 | 0.156 | ||

| CT | 0.550 | 0.670 | 0.780 | 0.850 | 0.940 | 0.940 | 1.020 | 1.030 | |||

| All | Female | Conventional | 0.074 | 0.082 | 0.095 | 0.093 | 0.099 | 0.094 | 0.097 | 0.097 | |

| CT | 0.440 | 0.560 | 0.660 | 0.740 | 0.830 | 0.830 | 0.890 | 0.900 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.057 | 0.060 | 0.063 | 0.058 | 0.062 | 0.058 | 0.060 | 0.059 | ||

| CT | 0.670 | 0.780 | 0.910 | 0.960 | 1.060 | 1.060 | 1.160 | 1.170 | |||

| <10 years | Female | Conventional | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| CT | 0.040 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.140 | 0.070 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 0.020 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | ||

| CT | 0.170 | 0.160 | 0.140 | 0.130 | 0.040 | 0.030 | 0.090 | 0.090 | |||

| ≥10, <20 years | Female | Conventional | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.030 | |

| CT | 0.080 | 0.070 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.120 | 0.180 | 0.180 | 0.180 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.027 | 0.034 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.037 | ||

| CT | 0.160 | 0.170 | 0.160 | 0.190 | 0.170 | 0.170 | 0.190 | 0.190 | |||

| ≥20, <30 | Female | Conventional | 0.033 | 0.033 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.041 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.042 | |

| CT | 0.130 | 0.160 | 0.270 | 0.250 | 0.310 | 0.360 | 0.410 | 0.410 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.037 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.043 | 0.044 | 0.047 | ||

| CT | 0.220 | 0.270 | 0.300 | 0.350 | 0.380 | 0.470 | 0.480 | 0.480 | |||

| ≥30, <40 | Female | Conventional | 0.039 | 0.039 | 0.047 | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.045 | 0.045 | |

| CT | 0.220 | 0.270 | 0.310 | 0.380 | 0.390 | 0.470 | 0.490 | 0.490 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.048 | 0.040 | 0.043 | 0.041 | 0.046 | 0.038 | ||

| CT | 0.290 | 0.420 | 0.390 | 0.420 | 0.460 | 0.670 | 0.590 | 0.600 | |||

| ≥40, <50 | Female | Conventional | 0.071 | 0.071 | 0.080 | 0.083 | 0.090 | 0.076 | 0.086 | 0.084 | |

| CT | 0.470 | 0.540 | 0.540 | 0.660 | 0.700 | 0.720 | 0.920 | 0.930 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.051 | 0.051 | ||

| CT | 0.440 | 0.520 | 0.630 | 0.700 | 0.710 | 0.900 | 1.210 | 1.220 | |||

| ≥50, <70 | Female | Conventional | 0.200 | 0.259 | 0.305 | 0.299 | 0.320 | 0.302 | 0.314 | 0.297 | |

| CT | 0.650 | 0.820 | 0.940 | 1.120 | 1.240 | 1.140 | 1.230 | 1.240 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.161 | 0.158 | 0.168 | 0.154 | 0.171 | 0.155 | 0.159 | 0.160 | ||

| CT | 1.040 | 1.210 | 1.350 | 1.470 | 1.760 | 1.560 | 1.810 | 1.830 | |||

| ≥70 | Female | Conventional | 0.427 | 0.394 | 0.436 | 0.416 | 0.428 | 0.420 | 0.415 | 0.433 | |

| CT | 0.980 | 1.340 | 1.610 | 1.680 | 1.960 | 1.930 | 1.930 | 1.950 | |||

| Male | Conventional | 0.243 | 0.223 | 0.252 | 0.221 | 0.220 | 0.212 | 0.219 | 0.223 | ||

| CT | 2.550 | 2.750 | 3.470 | 3.400 | 3.550 | 3.270 | 3.240 | 3.270 | |||

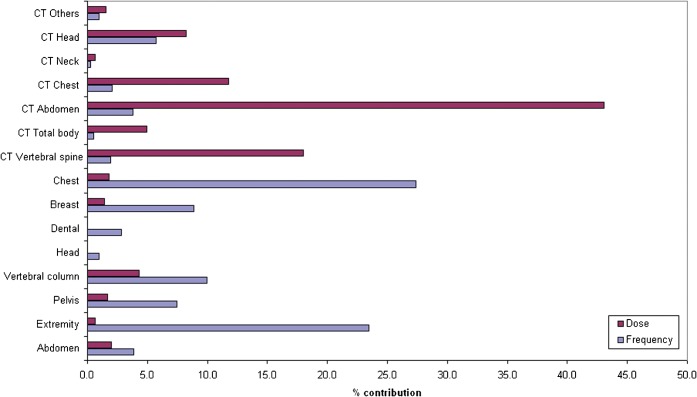

Finally, the relationship between percentage contribution to collective effective dose and examination frequency for the main contributors is reported in Figure 5 for the most recent year of the study.

Figure 5.

Collective effective dose and examination frequency of the main radiological examinations performed at the Radiological Department of Aosta Hospital in 2009.

Discussion

As is clearly illustrated in Figure 5, conventional radiography still represents the biggest contributor to examination frequency in Aosta Valley in 2009. However, data reported in Figure 1 show that the frequency of the main procedures did not change significantly between 2002 and 2009. In some cases, such as abdomen, head and chest examinations, the number of exams per 100 000 inhabitants has even decreased. This is certainly due to the growing use of other modalities such as CT, for which frequency has doubled in the period of the study.

Data reported in Table 3 show a limited increase (10%) in the number of examinations per 100 000 inhabitants for patients younger than 20 years. This general trend can be considered the result of the efforts made by radiologists to make medical doctors and patients aware of the radiation protection issues in CT use for paediatric patients. As a consequence of this awareness campaign, paediatric CT use has decreased, as illustrated in our previous paper [9], and conventional, lower-dose radiography increased.

On the contrary, the large increase observed for CT exams [9] can be considered the reason why the number of examinations does not significantly change for male patients between 20 and 70 years. The large increment registered for female patients may be ascribed to the increase of mammographic examinations due to the commencement of the regional breast-screening programme in 2003.

It should be noted that there are percentage increases of 40% and 26%, respectively, in frequency for female and male patients older than 70. This has also been reported in the literature [7]. It may be a consequence of an increased demand for diagnostic examinations, or decreased attention to radiation protection issues for the elderly population.

Finally, as reported by Fazel et al [13], females underwent radiographic procedures more often than males, with a difference in the number of examinations of about 10%, which remains practically constant over time.

The effective dose values of the main procedures are similar to recent estimates for other European countries [4-7], and directly comparable to those reported by the UNSCEAR for level I countries [1].

As shown in Figure 4, the biggest contributors to per caput effective dose from conventional radiology are the following examinations: vertebral column, abdomen, chest, pelvis and female breast. Leaving aside female breast, which was strongly influenced by the regional breast programme, only vertebral column and pelvis procedures show a significant per caput effective dose increase in the period of the study (41% and 51% for females, 32% and 58% for males, respectively), while we register the opposite trend for abdomen exams, as a consequence of the increasing use of CT.

The annual per caput effective dose reported in Table 5 is consistent with that assessed by UNSCEAR for level I countries [1], and with data reported in literature for France [5], the UK [14], Germany [15], the Netherlands [16] and Switzerland [17]. The mean effective dose per inhabitant increased from 0.68 mSv in 2002 to 1.19 mSv in 2009 (+75%). The contribution from conventional radiology increased from 0.131 mSv in 2002, accounting for 19% of the total, to 0.156 mSv (+19%) in 2009, accounting for 13% of the total. In contrast, the contribution of CT increased from 0.55 mSv (81% of the total) to 1.03 mSv (87% of the total). In general, we note that doses from radiological procedures are higher in males than in females, probably owing to height and weight differences. Further, doses also increase with increasing age. The overall result is a mean annual effective dose 2–3 times greater than would be expected from the annual natural background level, estimated of the order of about 1 mSv.

The observed increase in the collective effective dose is explained by the proliferation of high-dose CT procedures that, in spite of low frequency, give the highest contribution to CED, as is well illustrated in Figure 5. On the contrary, conventional radiology accounts for 85% of the total number of procedures, but only 13% of the total collective effective dose.

Calculated effective dose values have not been used for assessing radiation risks to the population of patients as suggested by the ICRP 103, considering that the relationship between effective dose and the probability of late radiation effects is critically dependent on the age and sex of the exposed population, and that the nominal probability coefficients for radiation-induced cancer given by ICRP have been derived for a general population only.

Finally, as also stressed in our previous paper [9], this work has demonstrated the role and the importance of radiological information systems. In our opinion, an RIS effectively integrated with the hospital information system represents not only a tool for better and faster planning of the activities of the radiological department, but can also provide data to support exposure justification and optimisation strategies as suggested by the European Directive 97/43/EURATOM.

Conclusions

Our study presents detailed information about the number and distribution of conventional radiological examinations performed at the radiological department of the Aosta Hospital from 2002 to 2009, and an accurate estimation of the effective dose to the population correlated with the main clinical examination protocols used.

The distribution of examinations by patients' age and sex, the number of exams and the effective dose per inhabitant are consistent with data published for other European countries, and confirm the assumption that the Valle d'Aosta region can be considered representative of the level I countries, as defined by UNSCEAR [1].

This study has proved that conventional radiology is still dominating the examination frequency in 2009, accounting for 85% of the total number of examinations, but only 13% of the total radiation exposure of the population from diagnostic medical sources. Even though conventional radiology has a low contribution to population exposure, we stress the importance of implementing adequate programmes of justification, dose evaluation and optimisation. To this aim, the present work has also demonstrated that an efficient and fully integrated radiological information system can play an important role, providing data to support radiologists, medical physicists and technicians in adopting the best strategies to keep the patient dose as low as possible.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Dr.ssa Patrizia Vittori of the Aosta Valley OREPS (Osservatorio Regionate Epidemiologico per le Politiche Sociali) for providing cancer mortality data.

References

- 1.United NationsScientificCommitteeontheEffectsofAtomicRadiation(UNSCEAR) Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. New York, NY: United Nations; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havukainen R, Pirinen M. Patient dose and image quality in five standard X-ray examinations. Med Phys 1993;20:813–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray JE, Archer BR, Butler PF, Hobbs BB, Mettler FA, Pizzutiello RJ, et al. Reference values for diagnostic radiology: application and impact. Radiology 2005;235:354–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Børretzen I, Lysdahl KB, Olerud HM. Diagnostic radiology in Norway—trends in examination frequency and collective effective dose. Rad Pro Dos 2007;124:339–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scanff P, Donadieu J, Pirard P, Aubert B. Population exposure to ionizing radiation from medical examinations in France. Br J Radiol 2008;81:204–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mettler AF, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology 2008;248:254–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shannoun F, Zeeb H, Back C, Blettner M. Medical exposure of the population from diagnostic use of ionizing radiation in Luxembourg between 1994 and 2002. Health Phys 2006;91:54–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compagnone G, Pagan L, Bergamini C. Local diagnostic reference levels in standards X-ray examinations. Rad Pro Dos 2005;113:54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catuzzo P, Aimonetto S, Zenone F, Fanelli G, Marchisio P, Meloni T, et al. Population exposure to ionizing radiation from CT examinations in Aosta Valley between 2001 and 2008. Br J Radiol 2010;83:1042–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cristy M, Eckerman KY. Specific absorbed fractions of energy at various ages from internal photon sources. VI: newborn. Oak Ridge National Laboratory Rep. ORNLffM-8381, vol. 6. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak RidgeNational Laboratory; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ICRP The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP publication 103. Ann ICRP 2007;37:1–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) Report 74. Patient dosimetry for X-rays used in medical imaging, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Ross JS, Chen J, Ting HH, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med 2009;361:849–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart D, Wall BF. UK population dose from medical X-ray examinations. Eur J Radiol 2004;50:285–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regulla D, Griebel J, Nosske D, Bauer B, Brix G. Acquisition and assessment of patient exposure in diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine. Z Med Phys 2003;13:127–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugmans MJP, Buijs WCA, Geleijns J, Lembrechts J. Population exposure to diagnostic use of ionising radiation in the Netherlands. Health Phys 2002;82:500–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aroua A, Burnand B, Decka I, Vader JP, Valley JF. Nationwide survey on radiation doses in diagnostic and interventional radiology in Switzerland in 1998. Health Phys 2002;83:46–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]