Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical and thin-section CT findings in patients with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and meticillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

Methods

We retrospectively identified 201 patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and 164 patients with acute MSSA pneumonia who had undergone chest thin-section CT examinations between January 2004 and March 2009. Patients with concurrent infectious disease were excluded from our study. Consequently, our study group comprised 68 patients with MRSA pneumonia (37 male, 31 female) and 83 patients with MSSA pneumonia (32 male, 51 female). Clinical findings in the patients were assessed. Parenchymal abnormalities, lymph node enlargement and pleural effusion were assessed.

Results

Underlying diseases such as cardiovascular were significantly more frequent in the patients with MRSA pneumonia than in those with MSSA pneumonia. CT findings of centrilobular nodules, centrilobular nodules with a tree-in-bud pattern, and bronchial wall thickening were significantly more frequent in the patients with MSSA pneumonia than those with MRSA pneumonia (p=0.038, p=0.007 and p=0.039, respectively). In the group with MRSA, parenchymal abnormalities were observed to be mainly peripherally distributed and the frequency was significantly higher than in the MSSA group (p=0.028). Pleural effusion was significantly more frequent in the patients with MRSA pneumonia than those with MSSA pneumonia (p=0.002).

Conclusions

Findings from the evaluation of thin-section CT manifestations of pneumonia may be useful to distinguish between patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and those with MSSA pneumonia.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common and important pathogens involved in nosocomial pneumonia, particularly because of the development of meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [1]. Pneumonia caused by MRSA is a clinically important type of pneumonia because of its severity, the high incidence of complications, and the increased mortality it causes in nosocomial pulmonary infections [2-4].

In recent years, MRSA has also emerged as an increasingly important cause of community-acquired bacterial infection, often affecting healthy children and adults who have no apparent risk factors for infection. community-acquired MRSA strains causing life-threatening infections, such as necrotising pneumonia and necrotising fasciitis, have been found to frequently carry Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) genes [5-7].

The mortality of pneumonia is usually associated with inadequate initial antibiotic therapy; therefore, early recognition of S. aureus pneumonia is important for reducing morbidity and mortality. Meanwhile bacteriological evaluation may take time and cause a delay in diagnosis. As such, thin-section CT may be helpful in expediting differential diagnosis of infections and in the selection of appropriate antibiotics. Recently, a small number of reports have emerged describing thin-section CT findings in patients with pathogens, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae [8-11]. As for S. aureus pneumonia, several studies have shown differences in clinical findings between MRSA pneumonia and meticillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) pneumonia [12-13]. In a radiological study, González et al [14] reported that there were no differences on chest radiographs between 32 patients with MRSA and 54 patients with MSSA. Nguyen and colleagues [15] reported CT findings in nine patients with community-acquired MRSA, whose conditions were characterised by extensive bilateral consolidation and frequent cavitation, which is commonly associated with rapid progression and clinical deterioration. However, there are currently very few reports with radiological findings in patients with MRSA or MSSA pneumonia. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no studies describing the comparison of CT findings in patients with MRSA with those with MSSA have been published. As such, the current study sought to evaluate thin-section CT findings of acute MRSA pneumonia compared with those with acute MSSA pneumonia.

Methods and materials

Patients

Our institutional review board approved this study, and because of its retrospective nature informed consent was not applicable.

We retrospectively identified 201 patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and 164 patients with acute MSSA pneumonia who had undergone chest thin-section CT examinations between January 2004 and March 2009 at our institutions.

Of the 201 patients with MRSA, we excluded 49 patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 44 with Candida albicans, 30 with K. pneumoniae, 9 with S. pneumoniae and some with other pathogens who had been diagnosed with concurrent infectious diseases by serological tests and clinical findings. Of the 164 patients with MSSA, 28 patients with MRSA, 12 with P. aeruginosa, 12 with C. albicans, 9 with K. pneumoniae, 9 with Streptococcus pneumoniae, and some with other pathogens who were diagnosed with concurrent infectious diseases were excluded from our study. Consequently, the final study group comprised 68 patients (37 male, 31 female, mean age 79.0 years, range 24–98 years) with acute MRSA pulmonary infection and 83 patients (32 male, 51 female, mean age 68.4 years, range 21 to 84 years) with acute MSSA pulmonary infection (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 151 patients with each type of pneumonia.

| MRSA |

MSSA |

|||

| Characteristics | (n=68) | (n=83) | ||

| M/F | 37/31 | 32/51 | ||

| Age (year) | ||||

| Range | 24–98 | 21–84 | ||

| Mean | 79 | 68.4 | ||

| Community-acquired | 13 (19.1) | 42 (50.6) | ||

| Nosocomial | 55 (80.9) | 41 (49.4) | ||

| Culture sample | ||||

| Sputum | 51 (75.0) | 66 (79.5) | ||

| Tracheal aspirate | 15 (22.1) | 15 (18.1) | ||

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.4) | ||

F, female; M, male; MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, meticillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Data in parentheses are percentages.

A diagnosis of pneumonia was made when the following features existed: symptoms of infection of cough, with or without sputum; fever, leukocytosis or leukopenia; and pulmonary infiltrates on the chest radiograph, coinciding with identification of MRSA or MSSA isolated from sputum (n=51, n=66, respectively), tracheal aspirate (n=15, n=15, respectively) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (n=2, n=2, respectively; Table 1).

A patient was considered to have community-acquired pneumonia if, at the time of hospital admission, he/she presented with respiratory symptoms and sputum, and exhibited pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiographs. No patient in our study had been admitted to or treated in a hospital in the 2 weeks prior to admission.

Frequencies of various underlying disease, alcoholism and smoking were measured. For the purposes of this study, an alcoholic was defined as an individual with a daily consumption of ≥80 g alcohol over the past 2 years [16], and a patient was considered to be a heavy smoker if he/she had smoked more than 10 pack-years.

CT examinations

Thin-section CT examinations were performed with 1 mm collimation at 10 mm intervals from the apex of the lung to the diaphragm (n=35), or volumetrically with a multidetector CT system with 1 mm reconstruction (n=116). CT examinations were performed with the patient in a supine position at full inspiration, and were reconstructed using a high spatial frequency algorithm. Images were captured at window settings that allowed viewing of the lung parenchyma (window level, −600 to −700 HU; window width, 1200–1500 HU), and the mediastinum (window level, 20–40 HU; window width, 400 HU).

The pulmonary CT examination was performed within 2–7 days (mean 5.1 days in the patients with MRSA, 4.8 days in the patients with MSSA) after the onset of respiratory symptoms.

Image interpretation

Two radiologists (with 21 and 13 years of experience in chest CT image interpretation), who were unaware of the underlying diagnoses, interpreted the CT images independently. Conclusions were reached by consensus.

CT images were assessed for the following radiological patterns: ground-glass attenuation (GGA), consolidation, nodules, centrilobular nodules, bronchial wall thickening, interlobular septal thickening, intralobular reticular opacity, bronchiectasis, enlarged hilar/mediastinal lymph node(s) (>1 cm diameter short axis), cavities and pleural effusion. Areas of GGA were defined as areas showing hazy increases in attenuation without obscuring vascular markings [17,18]. Areas of consolidation were defined as areas of increased attenuation that obscured the normal lung markings [17,18]. Centrilobular nodules were defined as those present around the peripheral pulmonary arterial branches or 3–5 mm from the pleura, interlobular septa or pulmonary veins. Moreover, centrilobular nodules were divided into the following two patterns: centrilobular nodules with a tree-in-bud appearance; and ill-defined centrilobular nodules of GGA without a tree-in-bud appearance. Tree-in-bud appearance was characterised by well-defined centrilobular nodules of soft-tissue attenuation that were connected to liner and branching opacities, thus resembling a tree in bud. Interlobular septal thickening was defined as abnormal widening of the interlobular septa [18]. Intralobular reticular opacity was considered to be present when interlacing line shadows were separated by a few millimetres [17,18].

The distribution of parenchymal disease was also noted. We assessed whether the abnormal findings were located unilaterally or bilaterally. If the main lesion was predominantly located in the inner third of the lung, the disease was classified as centrally distributed. On the other hand, if the lesion was predominantly located in the outer third of the lung, the disease was classified peripherally distributed. If the lesions showed no predominant distribution, the disease was classified as randomly distributed. In addition, zonal predominance was classified as upper, lower or random. Upper lung zone predominance indicated that most abnormalities were seen at a level above the tracheal carina, whereas lower zone predominance indicated that most abnormalities were located below the upper zone. When abnormalities showed no clear zonal predominance, the lung disease was classified as randomly distributed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for the frequency of symptoms and CT findings was conducted using Fisher's exact test and χ2 tests. A mean age comparison was conducted using Student's t-tests.

Results

Patients

In our examination of 201 patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and 164 patients with acute MSSA pneumonia, the frequency of concurrent pathogens found in patients with MRSA (n=133, 66.2%) was significantly higher than that in patients with MSSA (n=81, 49.4%) (p<0.005). P. aeruginosa, C. albicans and K. pneumoniae were significantly more frequently found in patients with MRSA than in patients with MSSA (n=49 vs n=12, n=44 vs n=12, n=30 vs n=9, respectively) (p<0.001, p<0.001, p<0.005, respectively).

The mean age of the patients with MRSA was higher than that of patients with MSSA (Table 1). The proportion of nosocomial infection was significantly higher in patients with MRSA than those with MSSA (p<0.001).

The underlying conditions and presenting symptoms of all patients are summarised in Table 2. Of all patients with MRSA and MSSA pneumonia, 62 were chronic smokers (n=30 and n=32, respectively) and 55 were alcoholics (n=25 and n=30, respectively), with no significant differences between groups.

Table 2. The underlying diseases and presenting symptoms in 151 patients.

| MRSA |

MSSA |

||

| Characteristics | (n=68) | (n=83) | p-value |

| Smoking habit | 30 (44.1) | 32 (38.6) | 0.489 |

| Alcoholic | 25 (36.8) | 30 (36.1) | 0.937 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 60 (88.2) | 51 (61.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (33.8) | 12 (14.5) | 0.005 |

| Pulmonary emphysema | 17 (25.0) | 16 (19.3) | 0.397 |

| Liver disorder | 8 (11.8) | 7 (8.4) | 0.496 |

| Collagen disease | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.4) | 0.84 |

| Renal failure | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.4) | 0.84 |

| Malignancy | 39 (57.4) | 12 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Lung cancer | 9 (13.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0.011 |

| Oesophageal cancer | 9 (13.2) | 3 (3.6) | 0.03 |

| Laryngo-pharyngeal cancer | 6 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.006 |

| Gastric cancer | 5 (7.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0.054 |

| Colon cancer | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0.447 |

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Cough | 64 (94.1) | 77 (92.8) | 0.741 |

| Sputum | 50 (73.5) | 27 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| Fever | 55 (80.9) | 66 (79.5) | 0.834 |

| Dyspnoea | 22 (32.4) | 15 (18.1) | 0.042 |

| General weakness | 4 (5.9) | 3 (3.6) | 0.51 |

MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, meticillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Data in parentheses are percentages.

With respect to underlying diseases, the frequencies of cardiovascular diseases (n=60, 88.2%), malignancy (n=39, 57.4%) and diabetes mellitus (n=23, 33.8%) in patients with MRSA were significantly higher than those in patients with MSSA (p<0.001, p<0.001, and p=0.005, respectively).

The most frequent presenting symptom in patients with acute MRSA pneumonia was cough (n=64, 94.1%), followed by fever (n=55, 80.9%) and sputum (n=50, 73.5%). The frequencies of sputum and dyspnoea were significantly higher in cases of MRSA than MSSA (p<0.001 and p=0.042, respectively).

CT patterns

The thoracic CT findings of the 151 patients are summarised in Table 3. In the 68 patients with MRSA pneumonia, GGA (n=54, 79.4%) and bronchial wall thickening (n=41, 60.3%) were most frequent, followed by consolidation (n=40, 58.8%), centrilobular nodules (n=32, 47.1%) and reticular opacity (n=23, 33.8%) (Figure 1). Bronchiectasis (n=9, 13.2%) and interlobular septal thickening (n=6, 8.8%) were also observed. Cavitary lesions were found in two patients (2.9%).

Table 3. Thoracic CT findings of the 151 patients with each type of pneumonia.

| Finding | MRSA (n=68) | MSSA (n=83) | p-value |

| Ground-glass attenuation | 54 (79.4) | 67 (80.7) | 0.841 |

| Bronchial wall thickening | 41 (60.3) | 63 (75.9) | 0.039 |

| Centrilobular nodules | 32 (47.1) | 53 (63.9) | 0.038 |

| Tree-in-bud pattern | 16 (23.5) | 37 (44.6) | 0.007 |

| Ill-defined nodules | 16 (23.5) | 16 (19.3) | 0.525 |

| Consolidation | 40 (58.8) | 43 (51.8) | 0.389 |

| Reticular opacity | 23 (33.8) | 21 (25.3) | 0.252 |

| Bronchiectasis | 9 (13.2) | 10 (12.0) | 0.827 |

| Interlobular septal thickening | 6 (8.8) | 7 (8.4) | 0.932 |

| Cavity | 2 (2.9) | 3 (3.6) | 0.818 |

| Nodules | 7 (10.3) | 6 (7.2) | 0.504 |

| Pleural effusion | 48 (70.6) | 38 (45.8) | 0.002 |

| Unilateral | 13 (19.1) | 10 (12.0) | 0.229 |

| Bilateral | 35 (51.5) | 28 (33.7) | 0.028 |

| Lymph node enlargement | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0.887 |

| Distribution | |||

| Unilateral | 24 (35.3) | 30 (36.1) | 0.914 |

| Bilateral | 44 (64.7) | 53 (63.9) | 0.914 |

| Upper zone | 14 (20.6) | 26 (31.3) | 0.137 |

| Lower zone | 47 (69.1) | 50 (60.2) | 0.258 |

| Central | 6 (8.8) | 3 (3.6) | 0.179 |

| peripheral | 48 (70.6) | 44 (53.0) | 0.028 |

MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, meticillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Data in parentheses are percentages.

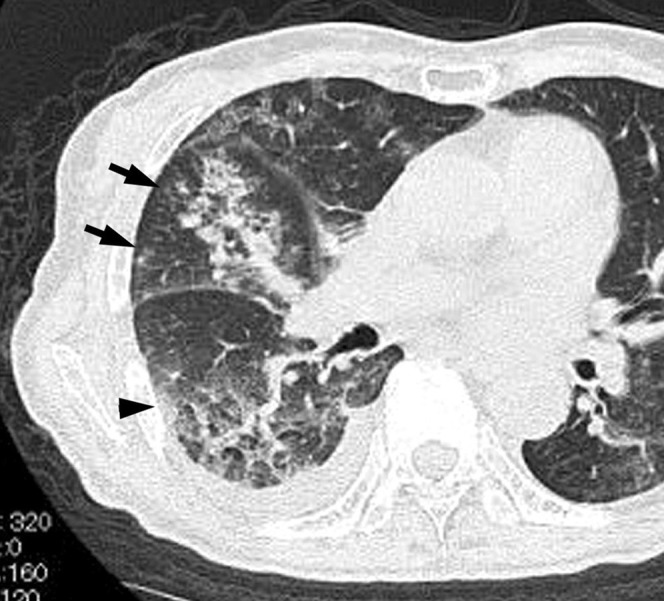

Figure 1.

Acute meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in a 74-year-old female with a smoking habit, cardiovascular disease and maxillary cancer, at 3 days after onset of fever, cough and dyspnoea. Transverse thin-section CT of the level of right B6 division shows consolidation, ground-glass attenuation (arrowhead) and ill-defined centrilobular nodules (arrows). Right pleural effusion was also present.

In the 83 patients with MSSA pneumonia, GGA (n=67, 80.7%) was most frequent, followed by bronchial wall thickening (n=63, 75.9%), centrilobular nodules (n=53, 63.9%), consolidation (n=43, 51.8%) and reticular opacity (n=21, 25.3%) (Figures 2 and 3). Bronchiectasis (n=10, 12.0%) and interlobular septal thickening (n=7, 8.4%) were also observed. Cavitary lesions were found in three patients (3.6%).

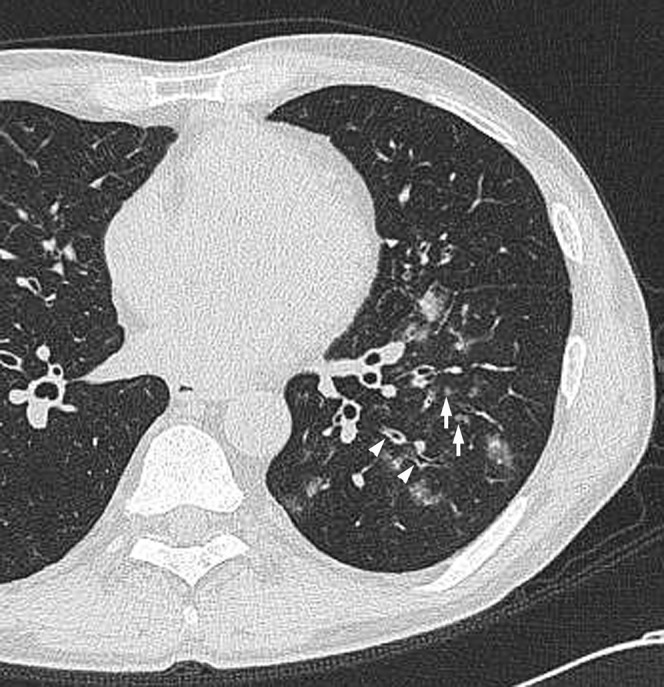

Figure 2.

Acute meticillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in a 54-year-old male with post-operative gastric cancer, at 4 days after onset of cough and sputum. Transverse thin-section CT of left lower lobe shows centrilobular nodules (arrows) and bronchial wall thickening (arrowheads).

Figure 3.

Acute meticillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in a 73-year-old female with cardiovascular disease, at 3 days after onset of cough, fever and sputum. Transverse thin-section CT of left upper lobe shows centrilobular nodules with tree-in-bud pattern (arrows) and bronchial wall thickening (white arrowhead).

The frequencies of bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodules were significantly higher in patients with MSSA than MRSA pneumonia (p=0.039 and p=0.038, respectively) (Figures 2 and 3). Moreover, the frequency of centrilobular nodules with a tree-in-bud pattern was significantly higher in patients with MSSA than MRSA pneumonia (p=0.007) (Figure 3). There were no significant differences in other CT findings including GGA and consolidation between the two groups.

Disease distribution

In the MRSA group, abnormal findings were found unilaterally in 24 patients (35.3%) and bilaterally in 44 patients (64.7%) (Table 3). The predominant zonal distribution was the upper zone in 14 patients (20.6%) and lower zone in 47 patients (69.1%) (Figure 1). In the MSSA group, abnormal findings were found unilaterally in 30 patients (36.1%) and bilaterally in 53 patients (63.9%). The predominant zonal distribution was the upper zone in 26 patients (31.3%) (Figure 3) and lower zone in 50 patients (60.2%) (Figure 2). There were no significant differences in zonal distributions between the two groups.

In the group with MRSA, parenchymal abnormalities were observed to be mainly peripherally distributed (n=48, 70.6%) and the frequency was significantly higher than in the MSSA group (n=44, 53.0%) (p=0.028).

Effusion and lymph nodes

Pleural effusion was found in 48 of 68 patients with MRSA (n=70.6%), and bilaterally in 35 patients (51.5%) (Table 3) (Figure 1). The frequency of pleural effusion was significantly higher in patients with MRSA than in those with MSSA pneumonia (p=0.002). In addition, the frequency which bilateral effusion was found bilaterally in was also significantly higher in patients with MRSA than those with MSSA (p=0.028).

Mediastinal and/or hilar lymph node enlargement was seen in one patient (1.5%) with MRSA pneumonia and in one patient (1.2%) with MSSA pneumonia. There was no significant difference between the two groups.

Follow-up study

All 151 patients underwent antibiotic therapy. In 58 of 68 patients with MRSA pneumonia, abnormal findings showed improvement on a follow-up CT examination or chest radiography. However, in the remaining 10 patients (14.7%), abnormal findings such as GGA, consolidation and reticular opacity were found to worsen on follow-up CT, and all of these patients subsequently died. In comparison, abnormal findings worsened in only 3 of the 83 patients with MSSA pneumonia. All three patients subsequently died (3.6%). The mortality rate in patients with MSSA was significantly lower than in patients with MRSA (p=0.016).

Discussion

Pneumonia due to S. aureus constitutes 1–10% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia [19-21] and 20–49% of cases of nosocomial pneumonia [22-24]. The treatment of MRSA pneumonia is considered to be clinically very important because of its severity, the high incidence of complications, and the increased mortality in nosocomial pulmonary infections [2-4]. Initially limited to hospitals, in recent years, MRSA has emerged as an increasingly prevalent cause of community-acquired bacterial infection, often affecting healthy children and adults with no apparent risk factors for infection.

The main clinical manifestations of MRSA infections, especially in community-acquired cases, include skin and soft-tissue abscesses, which may be recurrent and rapidly progressive, and potentially fatal necrotising pneumonia with a high prevalence of genes encoding PVL. Several case reports have emerged describing an increasing incidence of necrotising pneumonia resulting from MRSA infections that were commonly associated with parapneumonic effusion or empyema [25,26]. Unlike MSSA, effective antibodies for treating community-acquired MRSA are usually not part of initial empiric antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia. Therefore, the early recognition of MRSA pneumonia and initiation of appropriate antibiotics are important to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Several clinical studies have shown differences between MRSA pneumonia and MSSA pneumonia [4,5,12]. On the other hand, several studies have reported that the clinical manifestations of MRSA did not appear to differ from those of pneumonias due to other bacterial pathogens [13,14,27-29], and it appears that it is clinically difficult to differentiate manifestations of MRSA from those of MSSA.

Radiological findings of MRSA pneumonia reported in the current literature are limited to descriptions of necrotising pneumonia due to PVL-positive community-acquired MRSA without any detailed analysis of the extent, distribution and evolution of the radiographic and CT manifestations. Moreover, cases of PVL-positive MRSA make up only a small proportion of MRSA pneumonia cases, and PVL-positive community-acquired MRSA infections are even less commonly reported in Japan [30].

There have been very few publications describing differences in radiological findings among patients with MRSA and MSSA. In one study, González et al [14] compared 32 patients with MRSA and 54 with MSSA. No differences in clinical findings, radiological patterns using chest radiographs, or complications in clinical evolution were reported between patients with MRSA and those with MSSA pneumonia [14]. In this previous study, the radiological findings in both groups mainly demonstrated an alveolar pattern, followed by a nodular pattern. There were no differences between the two groups with respect to the presence of diffuse involvement of both lungs. One patient in each pneumonia group developed cavitation. In addition, the differences in the percentage of pleural effusion that developed in the two groups were also not significant.

Nguyen and colleagues [15] reported radiographic and CT findings in nine patients with community-acquired MRSA. The most common chest radiographic finding was consolidation, which was bilateral in seven patients and unilateral in two patients. The consolidation was patchy and non-segmental in five and segmental in four patients. The most common CT findings were bilateral (n=8), often symmetric (n=5) consolidation, and bilateral septal lines (n=7). However, these radiological findings were non-specific and difficult to distinguish from pneumonias with other pathogens [15].

A small number of reports regarding thin-section CT findings in patients with pneumonia in K. pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, S. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, and M. pneumoniae have recently been published [8-11,31]. However, no English-language studies of S. aureus examining pulmonary CT findings and no pulmonary thin-section CT findings in patients with acute S. aureus pneumonia have yet been published. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports comparing CT findings in patients with MRSA pneumonia with those in cases of MSSA pneumonia. This is the first study to focus on pulmonary CT findings in patients with MRSA pneumonia and MSSA pneumonia by using thin-section CT images.

We retrospectively identified 201 patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and 164 patients with MSSA pneumonia who had undergone thin-section CT chest examinations. For our comparative analysis between MRSA and MSSA pneumonia, we excluded 214 patients who exhibited other organisms cultured along with MRSA and MSSA, because in these cases it would be impossible to determine which organisms were primarily responsible for the radiological abnormalities. Thus, we retrospectively compared clinical and pulmonary thin-section CT findings in 68 patients with MRSA pneumonia alone with those of 83 patients with MSSA pneumonia alone.

Among our patient sample, the proportion of nosocomial infection in patients with MRSA was significantly higher than that in MSSA cases (p<0.001). With respect to underlying diseases, the frequencies of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and malignancy were significantly higher (p<0.001, p=0.005, p<0.001, respectively) in patients with MRSA than those with MSSA pneumonia. González et al [14], in a comparative study of MRSA and MSSA pneumonia, reported that lung diseases and vascular diseases were significantly more frequent among patients with MRSA pneumonia than cases of MSSA pneumonia. As the mean ages of the patients with MRSA were higher than those of patients with MSSA in both their report and in our study (68.6 vs 56.5, 79.0 vs 68.4, respectively), the frequencies of other underlying diseases (such as cardiovascular disease) in patients with MRSA pneumonia might have been higher than those in MSSA pneumonia. In addition, because MRSA pneumonia is usually of nosocomial origin, the underlying diseases including cardiovascular diseases or malignancy might allow more opportunity for MRSA to invade the patient, because treatment often involves invasive manoeuvres, e.g. insertion of central catheters. All patients in our sample had several complaints, such as fever and cough. The frequencies of sputum and dyspnoea in patients with MRSA pneumonia were significantly higher than those in patients with MSSA pneumonia, which might be related to the high frequency of underlying diseases.

Our thin-section CT findings in the 68 patients with MRSA pneumonia indicated that GGA and bronchial wall thickening were the most frequent features, followed by consolidation, centrilobular nodules and reticular opacity. Comparing CT results between the two groups revealed several important findings. Firstly, the frequencies of centrilobular nodules, particularly centrilobular nodules with tree-in-bud pattern, were significantly higher in cases of MSSA pneumonia than MRSA pneumonia (p=0.038 and p=0.007, respectively). Secondly, in the group with MRSA, parenchymal abnormalities were observed to be mainly peripherally distributed, and the frequency was significantly higher than in the MSSA group (p=0.028). Thirdly, the frequency of pleural effusion was significantly higher in patients with MRSA pneumonia than in those with MSSA pneumonia (p=0.002). In addition, bilateral pleural effusion was more common in MRSA patients than in MSSA patients (p=0.028).

Bronchopneumonia characteristic of infection with S. aureus differs pathogenetically from cases of airspace pneumonia such as K. pneumoniae pneumonia and C. pneumoniae pneumonia in the production of a relatively small amount of fluid and by the rapid inflammatory exudation of numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes. This typically occurs in relation to small membranous and respiratory bronchioles, resulting in a patchy and segmental appearance of the disease [32]. The early stages of the disease typically exhibit as an acute inflammatory exudation within the lumen of respiratory bronchioles, terminal bronchioles and immediately adjacent lung parenchyma histologically with a combined action of microbial toxins, resulting in the development of bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodules on CT images [32,33]. We recently reported thin-section CT findings in patients with acute K. pneumoniae pneumonia and C. pneumoniae pneumonia [8,11]. Bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodules were observed in 52 (26.3%) and 8 (4.0%) of 198 patients with acute K. pneumoniae pneumonia, respectively, and 14 (35.0%) and 3 (7.5%) of 40 patients with acute C. pneumoniae pneumonia, respectively. In the present study, the frequency of bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodules were significantly higher in cases of S. aureus pneumonia than in patients with K. pneumoniae pneumonia (MRSA, p<0.001 and p<0.001; MSSA, p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively) or acute C. pneumoniae pneumonia (MRSA, p<0.011 and p<0.001; MSSA, p<0.001 and p<0.001, respectively). Moreover, Collins et al [34] examined the toxicity of a genetically diverse population of clinical S. aureus and reported that the MSSA strains were significantly more toxic than MRSA strains. These findings suggest that the rapid exudation of numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes showed the higher prevalence of bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodular with tree-in-bud pattern in the MSSA group than in the MRSA group.

Duckworth and Jordens [35] conducted a study of adherence and survival properties comparing MRSA and MSSA strains and reported that MRSA bound to fibronectin, a glycopeptide thought to be central to the initial attachment of S. aureus to cells, significantly less well than MSSA. Furthermore, MRSA adhered to epithelial cells less well than MSSA [35]. In the present study, the appearance of a peripheral-dominant distribution was more frequent among patients with MRSA pneumonia than among those with MSSA pneumonia. This result may be attributed to the adherence properties of each organism. MRSA has fewer properties of adherence to epithelial cells than MSSA. This may be advantageous to its progression into more peripheral areas compared with MSSA, resulting in the predominance of its peripherally distributed appearance. Similarly, as for pleural effusion, the same properties may enable MRSA to produce inflammatory exudation at more peripheral sites, resulting in the more prevalent appearance of pleural effusion on CT findings in cases of MRSA pneumonia. In addition, the high frequency of underlying disease such as cardiovascular diseases and the higher average age of patients with MRSA may be involved in the higher frequency of pleural effusion than in MSSA patients.

Several limitations of the current study should be considered. Firstly, this was a retrospective study, and CT images were interpreted by consensus. Secondly, we were unable to make a pathological correlation between specific CT findings such as GGA, bronchial wall thickening and centrilobular nodules. Thirdly, it may be difficult to distinguish these CT findings from those associated with the other bronchopneumonia such as Haemophilus influenzae, M. catarrhalis and P. aeruginosa. However, it is important to determine the clinical and radiological differences between the MRSA group and the MSSA group. Fourthly, the thin-section CT images were obtained at our institutions using different protocols.

In summary, we investigated clinical and thin-section CT findings in 68 patients with acute MRSA pneumonia and 83 patients with acute MSSA pneumonia. Underlying diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, were significantly more frequent in patients with MRSA pneumonia than those with MSSA pneumonia. Our CT findings revealed that centrilobular nodules (especially with the tree-in-bud pattern), and bronchial wall thickening were significantly more frequent in patients with MSSA pneumonia than in those with MRSA pneumonia. On the other hand, pleural effusion was more frequently observed in cases of MRSA compared to MSSA pneumonia.

References

- 1.Lipchik RJ, Kuzo RS. Nosocomial pneumonia. Radiol Clin North Am 1996;34:47–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijaya L, Hsu LY, Kurup A. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: overview and local situation. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006;35:479–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalopoulos A, Falagas ME. Multi-systemic methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) community-acquired infection. Med Sci Monit 2006;12:CS39–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwahara T, Ichiyama S, Nada T, Shimokata K, Nakashima N. Clinical and epidemiologic investigations of nosocomial pulmonary infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Chest 1994;105:826–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the role of Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Lab Invest 2007;87:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandenesch F, Naimi T, Enright MC, Lina G, Nimmo GR, Heffernan H, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying panton-valentine leukocidin genes: world wide emergence. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:978–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen RJ, Burns KM, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Musser JM. Severe necrotizing fasciitis in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:1144–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada F, Ando Y, Honda K, Nakayama T, Kiyonaga M, Ono A, et al. Clinical and pulmonary thin-section CT findings in acute Klebsiella Pneumoniae pneumonia. Eur Radiol 2009;19:809–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nei T, Yamano Y, Sakai F, Kudoh S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: differential diagnosis by computerized tomography. Intern Med 2007;46:1083–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nambu A, Saito A, Araki T, Ozawa K, Hiejima Y, Akao M, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae: comparison with findings of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Streptococcus pneumoniae at thin-section CT. Radiology 2006;238:330–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada F, Ando Y, Wakisaka M, Matsumoto S, Mori H. Chlamydia pneumonia pneumonia and Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: comparison of clinical findings and CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005;29:626–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JL, Chen SY, Wang JT, Wu GH, Chiang WC, Hsueh PR, et al. Comparison of both clinical features and mortality risk associated with bacteremia due to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:799–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershow RC, Khayr WF, Smith NL. A comparison of clinical virulence of nosocomially acquired methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infections in a university hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1992;13:587–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González C, Rubio M, Romero-Vivas J, González M, Picazo JJ. Bacteremic pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus: a comparison of disease caused by methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible organisms. Clin Infect Dis 1999;29:1171–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen ET, Kanne JP, Hoang LM, Reynolds S, Dhingra V, Bryce E, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: radiographic and computed tomography findings. J Thorac Imaging 2008;23:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres A, Serra-Batlles J, Ferrer A, Jimenez P, Celis R, Cobo E, et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Epidemiology and prognostic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:312–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. High-resolution computed tomography findings of lung disease. High-resolution CT of the lung, 3rd edn Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008;246:697–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang GD, Fine M, Orloff J, Arisumi D, Yu VL, Kapoor W, et al. New and emerging etiologies for community-acquired pneumonia with implications for therapy: a prospective multicenter study of 359 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:307–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayser FH. Changes in the spectrum of organisms causing respiratory tract infections: a review. Postgrad Med J 1992;68:17–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller RF, Foley NM, Kessel D, Jeffrey AA. Community acquired lobar pneumonia in patients with HIV infections and AIDS. Thorax 1994;49:367–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:867–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:3854–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pennington JE. Hospital-acquired pneumonia. Pennington JE, Respiratory infections: diagnosis and management, 3rd edn New York, NY: Raven Press; 1994. pp.207–27 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fergie JE, Purcell K. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in south Texas children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:860–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston BL. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a cause of community-acquired pneumonia—a critical review. Semin Respir Infect 1994;9:199–206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, Borchardt SM, Boxrud DJ, Etienne J, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA 2003;290:2976–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeRyke CA, Lodise TP, Jr, Rybak MJ, McKinnon PS. Epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes of nosocomial bacteremic Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:1414–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, Mostafaie K, Bharadwa K, Tan N, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:483–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomita Y, Kawano O, Ichiyasu H, Fukushima T, Fukuda K, Sugimoto M, et al. Two cases of severe necrotizing pneumonia caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. [In Japanese] Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 2008;46:395–403 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheepsattayakorn A, Tharavichitakul P, Dettrairat S, Sutachai V. Moraxella catarrhalisis pneumonia in an AIDS patient: a case report. J Med Assoc Thai 2009;92:284–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser RS, Muller NL, Colman NC, Pare PD. Diagnosis of diseases of the chest. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashizawa K, Uetani M. Radiographic imaging of bacterial pneumonia. Nippon Rinsho 2007;65:231–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins J, Buckling A, Massey RC. Identification of factors contributing to T-cell toxicity of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:2112–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duckworth GJ, Jordens JZ. Adherence and survival properties of an epidemic methicillin-resistant strain of staphylococcus aureus compared with those of meticillin-sensitive strains. J Med Microbiol 1990;32:195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]