Abstract

With increasing numbers of patients experiencing chronic pain, opioid therapy is becoming more common, leading to increases in concern about issues of abuse, diversion, and misuse. Further, the US Food and Drug Administration recently released a statement notifying sponsors and manufacturers of extended-release and long-acting opioids of the need to develop Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) programs in order to ensure that the benefits of this therapy choice outweigh the potential risks. There is little research on physician opinions concerning opioid-prescribing and education policies. To assess attitudes surrounding new opioid policies, a survey was designed and distributed to primary care physicians in October 2011. Data collected from 201 primary care physicians show that most are not familiar with the REMS requirements proposed by the Food and Drug Administration for extended-release and long-acting opioids; there is no consensus among primary care physicians on the impact of prescribing requirements on patient education and care; and increasing requirements for extended-release and long-acting opioid education may decrease opioid prescribing. Physician attitudes toward increased regulatory oversight of opioid therapy prescriptions should be taken into consideration by groups developing these interventions to ensure that they do not cause undue burden on already busy primary care physicians.

Keywords: REMS, opioids, attitudes, survey

Introduction

A major public health problem in the US, chronic pain has been estimated to affect up to a third of Americans. However, following a decade of standard setting and research on pain control,1 health care practitioner assessment and management of patient pain continues to be inadequate. Evidence-based guidelines2 emphasize thorough patient assessment, prompt recognition of patient pain, frequent monitoring, multimodal analgesic therapies, and patient input; however, there are persistent gaps in clinicians’ knowledge and practice around key areas of chronic pain management. In addition, misuse and abuse of nonprescription medications have remained consistent over the past decade, resulting in addiction, drug poisoning, and overdose death.3 While these issues remain a reality, there are appropriate uses for opioids that can greatly improve a patient’s quality of life. Thus, education on best practices for opioid safe use is critical for all clinicians managing patients with chronic pain.

To address the public health problem of opioid-related addiction, overdose, and death, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has implemented the opioid Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) program as part of a multifaceted federal initiative. The REMS program provides guidance on new safety measures aimed at reducing risks and improving safe use associated with extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids, without a concomitant negative impact on patient access to powerful medications for patients who require them. Currently, the FDA REMS program affects more than 20 companies and more than 30 products. The new FDA REMS requirements call for companies that manufacture ER/LA opioid analgesics to provide training for clinicians who prescribe these opioids related to appropriate prescribing practices as well as to develop and disseminate provider and patient educational materials on opioid safe use. In addition, the FDA is requiring all REMS programs to have an assessment component to measure impact and effectiveness. However, little is known about the current attitudes of physicians towards REMS, especially in the context of ER/LA opioid prescribing.

Although a white paper published by the American Pharmacists Association4 on designing a REMS system included information regarding physician experiences with REMS, only two of the nine participants in the stakeholder meeting were physicians and it only addressed REMS in general, not specific to opioids. Thus, generalizations about physician attitudes towards REMS based on the information in this report would be speculative. Further research5 addressed general physician prescribing habits based on REMS for opioid prescribing and demonstrated that physicians were not likely to follow REMS in all cases despite restrictions. A previous study6 found that while pain specialists appeared to be somewhat familiar with the proposed requirements for opioid REMS, primary care physicians were not. Additionally, attitudes regarding these policies were middling, indicating general unawareness about the potential impact REMS will have on their practice.

Based on the available research, it would seem that a large gap in the medical literature exists regarding the level of physician familiarity with REMS, attitudes towards REMS, participation in REMS programs, and perceptions of effectiveness of REMS with regard to prescription patterns and safety outcomes. The aim of this study was to characterize the attitudes and perceptions of primary care physicians on the proposed REMS policies and how they may impact patient care.

Materials and methods

This study was designed to assess attitudes among primary care physicians related to the management of patients with chronic pain, particularly in the areas of discussion of risk and safe use and federal opioid prescribing requirements. A literature review was conducted to examine previous research, and subsequently a survey was developed and implemented to assess the attitudes of primary care physicians.

Literature review

Searches for articles in peer-reviewed journals related to REMS and management of chronic pain were made in Medline, Search Medica, and on the Internet. Attention was directed to studies conducted in the US, but relevant studies from Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union were eligible for inclusion. This review found that there is a lack of national studies on physician attitudes related to risks and safe use of opioid therapy, particularly in the areas of patient communication and federal policy.

Survey instrument development and implementation

Based on the literature review, a survey instrument was developed to assess physician awareness and attitudes related to opioid REMS, as well as potential physician education and patient barriers toward prescribing currently available and emerging ER/LA opioids. Physician educational barriers refer to particular difficulties that increased education will have on prescribing opioids; patient barriers refer to particular requirements, such as patient education and national registries.

Inclusion criteria for this survey, enforced by screening questions within the survey, were as follows:

The respondent must be a practicing physician

The respondent must prescribe opioids for acute pain, chronic cancer-related pain, or chronic noncancer pain

The respondent must prescribe ER/LA opioids.

A link to an online survey was distributed by email during October 2011 to a proprietary national mailing list that included 993 general internists and family physicians; 296 physicians responded to the invitation (response rate 29.8%). After removing the 75 physicians who did not meet the study criteria and 20 who did not complete all of the assessment questions, 201 physicians were included in the final analysis (20.2% of those invited by email).

Analysis

Data were compiled and analyzed using PASW Statistics package version 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and means, were calculated for all items in the survey to examine overall responses and related trends among the survey items. Correlations and other comparative analyses were conducted, where appropriate, to analyze relationships among key variables. Items captured from an open-ended comment box are included in the discussion where appropriate to support the findings.

Results

Sample

The sample for this study, as shown in Table 1, is composed entirely of primary care physicians well established in their practices (mean of 23 years since graduation from medical school). These physicians see an estimated 27 patients with chronic noncancer pain each week and 16 patients with a prescription for ER/LA opioids each week. Most of the physicians in the sample have had at least some training in managing patients with opioids. While nearly two thirds of the sample have participated in continuing education programs on safe and effective treatment with opioids in the past 2 years, almost one third of the sample has had no education at all on this topic.

Table 1.

Demographics of sample

| PCPs (n = 201) | |

|---|---|

| Degree, MD/DO | 100.0% |

| Specialty | |

| Family medicine | 49.3% |

| Internal medicine | 50.7% |

| Gender, male | 68.2% |

| Years since medical school graduation, mean (SD) | 23 (10) |

| Attended medical school in US | 74.6% |

| Patients seen per week, mean (SD) | 112 (63) |

| Patients with chronic noncancer pain seen per week, mean (SD) | 27 (25) |

| Patients with prescription for long-acting/extended release opioid seen per week, mean (SD) | 16 (27) |

| Practice size | |

| Solo | 28.4% |

| Small group (1–5) | 39.8% |

| Large group (>5) | 31.8% |

| Physicians in practice, mean (SD) | 10 (22) |

| Practice location | |

| Urban | 35.8% |

| Suburban | 46.8% |

| Rural | 17.4% |

| Has nurse practitioner or physician assistant in practice | 50.2% |

| Currently prescribe opioids for | |

| Acute pain | 99.0% |

| Chronic cancer-related pain | 90.0% |

| Chronic noncancer pain | 96.5% |

| Participation in educational programs on safe and effective opioid use in past 2 years | |

| REMS certification/training program required for prescribers | 6.0% |

| Voluntary REMS certification/training program | 4.0% |

| Continuing medical education program | 64.2% |

| Other | 4.0% |

| None | 31.8% |

Abbreviations: PCPs, primary care physician; SD, standard deviation; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Familiarity with opioid REMS

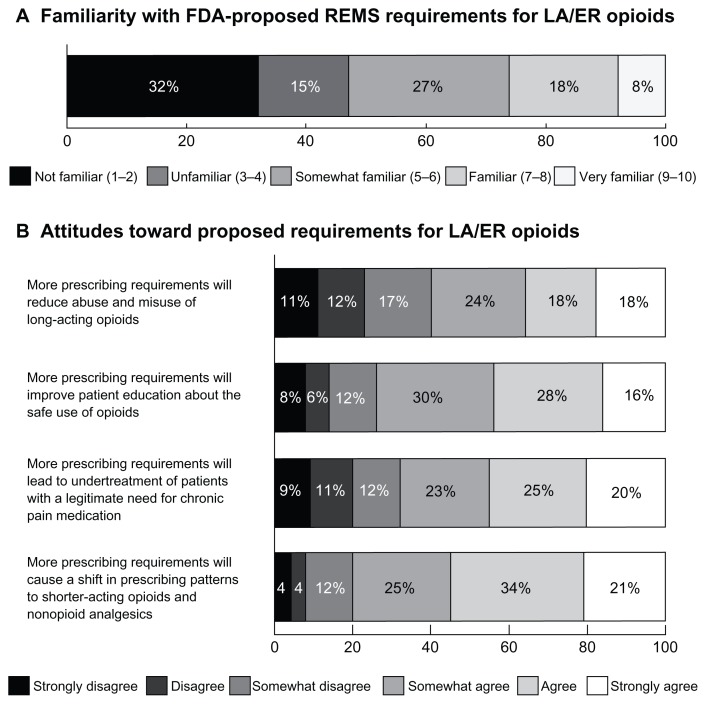

The primary care physicians in the sample were asked to rate their familiarity with the REMS policy proposed by the FDA for ER/LA opioids on a 10-point scale. Few physicians rated their familiarity as ≥7, and nearly a third indicated that they were not familiar with these requirements (1–2 rating, Figure 1). Familiarity was moderately correlated with participation in an educational program on safe and effective use of opioids (r = 0.393, P< 0.001), as well as the number of patients with chronic noncancer pain (r = 0.266, P = 0.001) and number of patients with ER/LA opioid prescriptions (r = 0.325, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Familiarity and attitudes towards requirements proposed by the US Food and Drug Administration for ER/LA opioids. (A) Nearly a third of the primary care physicians in the sample (n = 201) reported that they were not familiar with REMS requirements proposed by the US Food and Drug for ER/LA opioids, rating familiarity as 1 or 2 on a 10-point scale. (B) Physicians vary widely on the effects of prescribing requirements on patient care (n = 201).

Notes: There is no consensus amongst surveyed physicians on whether prescribing requirements will reduce abuse and misuse of ER/LA opioids, improve patient education, lead to under-treatment, or cause a shift to shorter-acting therapies.

Abbreviations: FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ER/LA opioids, extended-release/long-acting opioids; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.

Attitudes towards REMS requirements

Physicians in the sample were asked to rate their attitudes toward a number of statements on how additional prescribing requirements will affect the care of patients with chronic pain. Specifically, they were asked to rate whether additional requirements for opioid prescription will reduce abuse/misuse, improve patient education on the safe use of opioid analgesics, lead to the under treatment of patients with chronic pain, and cause a shift to prescription of shorter-acting or nonopioid analgesics. The responses indicate that perceptions of how prescribing requirements may impact patient care vary widely. Many physicians remain uncertain about the value of these requirements for their patients (Figure 1).

Impact of REMS components on patient care

REMS programs generally have multiple components which may include a medication guide (paper handouts that come with many prescription medicines), elements to assure safe use (ETASU, ie, information beyond education materials, such as physician or pharmacist training/certification, criteria-specific dispensing of medication, patient monitoring, or patient registries), an implementation system (monitoring and evaluation of whether ETASU are being observed by clinicians), and a communication plan (dissemination of information necessary for appropriate use of a product to healthcare providers, including, but not limited to, an introductory letter and package inserts). Physicians were asked which of these potential components of an opioid prescribing requirements program will have the greatest positive impact on patient care, which will have the greatest negative impact, and which will have no impact. Of the components of REMS programs, physicians are more likely to believe that ETASU will have the greatest positive impact on patient care and an implementation system will have the greatest negative impact (Table 2). Over half of physicians indicated that medication guides will have no impact on patient care.

Table 2.

Impact of potential components of opioid prescribing requirements on patient care (n = 201)

| Greatest positive impact on patient care | Greatest negative impact on patient care | No impact on patient care* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication guide | 17.4% | 16.9% | 59.7% |

| Elements to assure safe use | 38.8% | 21.9% | 13.4% |

| Implementation system | 19.9% | 49.8% | 14.9% |

| Communication plan | 23.9% | 11.4% | 23.9% |

Note:

Respondents were allowed to select more than one option.

Barriers to opioid prescription

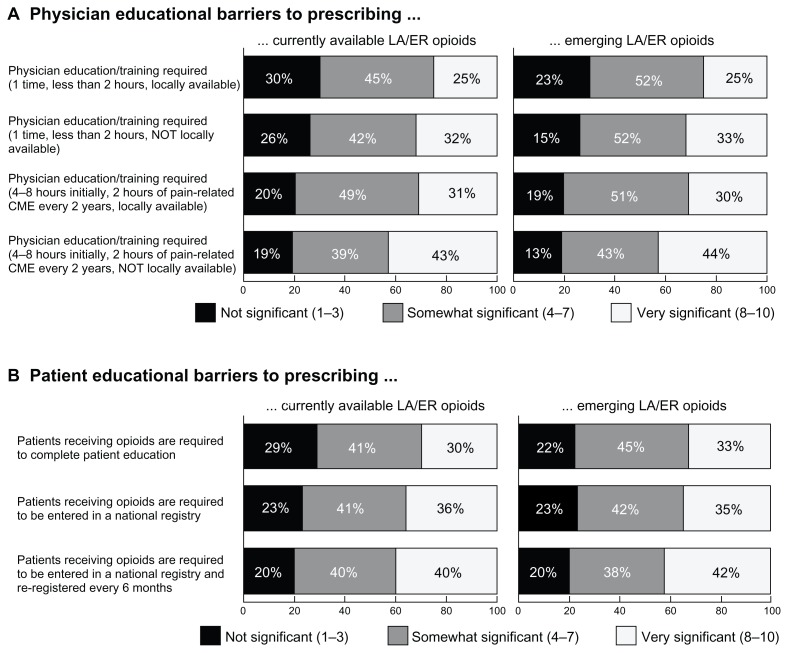

Physicians were asked to rate the significance of various potential barriers to prescribing currently available and emerging ER/LA opioids. As shown in Figure 2A, increasing time burden and distance for opioid training increases the perceived significance of the barrier. Primary care physicians also seem more likely to find training on emerging opioid therapies more burdensome than equal training on currently available therapy.

Figure 2.

Physician and patient barriers to opioid prescription. (A) Respondents were asked to rate how significant certain potential requirements would be when prescribing currently available and emerging ER/LA opioids (n = 201). Locally available training and less time spent on mandatory education are factors seen as less burdensome to prescribing either set of opioids. Physicians also seem more likely to find training on currently available medications less burdensome than emerging therapies. (B) A third of surveyed primary care physicians (n = 201) would consider requiring patients receiving opioids to complete patient education to be a significant barrier to prescribing these therapies.

Note: The burden to prescription increases if regulations require national patient registries.

Abbreviation: ER/LA opioids, extended-release/long-acting opioids; CME, continuing medical education.

Responses to the burden of locally available training requirements for emerging therapies vary significantly by physician practice size, but not years in practice or patient load. Chi-square analysis shows physicians in smaller practices are less likely than those in larger practices to find these requirements significant, whether the time requirements are less than 2 hours (P = 0.028) or 4–8 hours plus additional training every two years (P = 0.030). Physicians in rural practice settings find participating in one-time education for current or emerging ER/LA opioids to be significantly less burdensome than physicians in urban or suburban settings, whether locally available or not.

Roughly a third of primary care physicians indicated that proposed policies requiring patients receiving opioids to complete patient education would be a significant barrier to prescribing these therapies, rating the barrier as 8–10 on a 10-point scale (Figure 2B). The physicians’ perceived burden to prescribe increased if policies require national patient registries. Additionally, increased physician patient load (more patients with chronic noncancer pain and patients with prescriptions for ER/LA opioids) is correlated with higher significance of all these patient barriers (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The data presented here show that many primary care physicians who treat patients with chronic pain are cautious about the potential impact of the additional requirements that REMS policies may place on them and their patients. Furthermore, several areas of need and future education are highlighted by these results. All of the physicians in this study currently prescribe ER/LA opioids for their patients, but only 8% are “very familiar” with the REMS requirements proposed by the FDA for these medications. Many primary care physicians in this study believe that increased requirements will have negative effects on the management of chronic pain without necessarily improving patient education or reducing abuse and misuse. Additionally, over half of primary care physicians believe that a medication guide included in these requirements will have no impact on patient care; 24% believe that communication plans will also have no effect. Medication guides are utilized in many approved REMS, and in many cases are the only component of the risk-prevention strategy.7

These attitudes need to be considered when developing future policies and educational interventions regarding the safe use of opioids. Physicians, specifically primary care physicians, are in need of assistance in managing patients with chronic pain, but policies need to be practical and have evidence for improving patient outcomes. The primary care physicians surveyed in this study are not convinced that these requirements will be of much benefit, but very few of them are extremely familiar with the current FDA proposals. Broad dissemination of these requirements may be necessary to allow busy physicians to understand fully how these new policies will affect them and their patients.

Currently, there is no incentive or penalty for physicians to participate in required activities, evidenced by the few physicians who have gone through mandatory or voluntary REMS training in the past two years. One respondent questioned the impact of additional training: “Double-edged ... would patient care be improved because [of] the proposed intervention ... or would it be worse because doctors would be so hassled by yet another requirement that they would be less willing to provide this care?” If policymakers would like to see increased attendance to these types of events, a “carrot/stick” approach may need to be used to give physicians a reason to attend, much like the HITECH Act incentivizes the use of electronic health record systems in physician offices.8

Perhaps not surprisingly, increasing the requirements for time spent in opioid education or the distance required to travel for opioid education increases physicians’ perception of burden related to prescription of ER/LA opioids. Previous research on opioids 5 showed similar results, ie, just under a third of physicians would discontinue opioid prescribing if they were mandatory requirements for physician education. Additionally, physicians seem wary of increased patient responsibility for opioid prescriptions because many assume, perhaps correctly, that this will increase demand on their offices just as much. A survey respondent commented, “If [the] patient does the registering for chronic pain meds – fine – but if we are required to do more than what we are already burdened with, this will backfire”. Any requirements for mandatory education on prescribing opioids should consider the impact they will have on access to care. Most of the physicians surveyed seemed amenable to these requirements, as long as they do not greatly impede on their time with patients. To this end, one survey respondent commented that “a requirement for continuing education program training and education on a one-time basis prior to having a license to prescribe narcotics would be very appropriate”.

Several publications have examined the effects of FDA safety warnings on physician prescribing behavior. While some suggested that warnings were effective in changing prescribing patterns in accordance with safety recommendations,9–11 other studies demonstrated that physicians were less apt to change their practice patterns with regard to the recommendation for more frequent patient contact.9,12 Studying the impact of a warning letter pertaining to seizure risk associated with tramadol and concomitant use of antidepressants, researchers found that the warning letter had no measurable effect on physician prescribing patterns.13 Data from a study examining the effects of multiple warning letters pertaining to cisapride and several medications contraindicated for concomitant use suggested that explicit information was more effective than implied language in changing physician prescribing patterns, but that the explicit nature of the letters alone was not necessarily sufficient.14 The level of publicity surrounding the warning letters was found to be a critical component in bringing about changes in physician behavior. These results highlight the need for specific monitoring of the effectiveness of interventions of this type and the need for education surrounding proper implementation of warnings to maximize their intended effects.

Limitations

This study used a survey as a surrogate measure of primary care clinicians’ self-reported skills, knowledge, and attitudes. While physician self-reporting has been shown to have limited accuracy, the data provided show trends that should be addressed in future educational interventions. Respondents were given a small honorarium to complete the study, which could have influenced participation rates and responses. However, the demographic characteristics of our sample were not different in gender, years since graduation, or practice size from that of the overall population of primary care physicians (compared with 2009 information from the American Medical Association). The cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for causal inferences to be drawn, and a repeat of this study may be warranted on an annual basis to examine practice pattern trends, especially as more physicians become familiar with REMS or if proposed requirements become mandatory. The response rate for this study fell at under 30%; this may show some respondent bias. Finally, our study only examined primary care physicians; as such, the data can only be interpreted for this population. Other studies may be needed to examine the knowledge, attitudes and practice patterns of nonprimary care physicians who treat patients with chronic pain.

Conclusion

This study highlights the fact that many primary care physicians are unsure about the effect opioid REMS may have on their management of patients with chronic pain. Many are cautious about further governmental monitoring and increased regulatory training, which may lead to less prescription of ER/LA opioids and access to care. While increased caution in prescribing opioids is appropriate, this could lead to qualifying patients not receiving the best treatment for their condition. Future REMS programs should take physicians’ needs into account because they may present opportunities for educators to offer physicians support and strategies for fulfilling REMS requirements. Furthermore, these data suggest that all REMS components should be continually monitored and tested to assure all stakeholders that they are accomplishing their intended goals.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This research was funded solely by CE Outcomes LLC, an independent healthcare assessment company. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose in this work.

References

- 1.Lippe PM. The decade of pain control and research. Pain Med. 2000;1:286. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon DB, et al. American Pain Society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1574–1580. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No (SMA) 11-4658. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Pharmacists Association. White paper on designing a risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) system to optimize the balance of patient access, medication safety, and impact on the health care system. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49:729–743. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slevin KA, Ashburn MA. Primary care physician opinion survey on FDA opioid risk evaluation and mitigation strategies. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7:109–115. doi: 10.5055/jom.2011.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salinas GD, Susalka D, Burton BS, et al. Risk assessment and counseling behaviors of healthcare professionals managing patients with chronic pain: a national multi-faceted assessment of physicians, pharmacists, and their patients. J Opioid Manag. 2012 doi: 10.5055/jom.2012.0127. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) [Accessed December 2, 2011]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm.

- 8.United States Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. EHR Incentive Programs. [Accessed June 12, 2012]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/EHRIncentivePrograms.

- 9.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss BG. Effects of Food and Drug Administration warnings on antidepressant use in a national sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busch SH, Frank RG, Leslie DL, et al. Antidepressants and suicide risk: how did specific information in FDA safety warnings affect treatment patterns? Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:11–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassanin H, Harbi A, Saif A, Davis J, Easa D, Harrigan R. Changes in antidepressant medications prescribing trends in children and adolescents in Hawai’i following the FDA black box warning. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69:17–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al. Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:42–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shatin D, Gardner JS, Stergachis A, Blough D, Graham D. Impact of mailed warning to prescribers on the co-prescription of tramadol and antidepressants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:149–154. doi: 10.1002/pds.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weatherby LB, Nordstrom BL, Fife D, Walker AM. The impact of wording in “Dear doctor” letters and in black box labels. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:735–742. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]