Abstract

Significance: The family of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) is part of a cellular Phase II detoxification program composed of multiple isozymes with functional human polymorphisms that have the capacity to influence individual response to drugs and environmental stresses. Catalytic activity is expressed through GST dimer-mediated thioether conjugate formation with resultant detoxification of a variety of small molecule electrophiles. Recent Advances: More recent work indicates that in addition to the classic catalytic functions, specific GST isozymes have other characteristics that impact cell survival pathways in ways unrelated to detoxification. These characteristics include the following: regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases; facilitation of the addition of glutathione to cysteine residues in certain proteins (S-glutathionylation); as a novel cellular partner of the human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein playing a pivotal role in preventing cell death in infected human cells; mitogenic influence in myeloproliferative pathways; participant in the process of cocaine addiction. Critical Issues: Some of these functions have provided a platform for targeting GST with novel small molecule therapeutics, particularly in cancer where evidence of clinical applications is emerging. Future Directions: Our evolving understanding of the GST superfamily and their divergent expression patterns in individuals make them attractive candidates for translational studies in a variety of human pathologies. In addition, their role in regulating cell fate in signaling and cell death pathways has opened up a significant functional complexity that extends well beyond standard detoxification reactions. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1728–1737.

Introduction

Human glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are divided into three main families: cytosolic, mitochondrial, and membrane-bound microsomal. Microsomal GSTs have been described as membrane-associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism and are structurally distinct from cytosolic GST. However, they still maintain an ability to catalyze the conjugation of glutathione (GSH) to electrophiles (25). Mammalian cytosolic GST are monomeric, but catalytically active as homo- or heterodimers (34) and are divided into seven classes earlier based upon the Greek alphabet (newer nomenclature uses Latin script) alpha (A), mu (M), omega (O), pi (P), sigma (S), theta (T), and zeta (Z). Classification is essentially based on sharing >60% identity within a class and focuses mainly on the more highly conserved N-terminal domains containing catalytically active tyrosine, cysteine, or serine residues. The catalytic residue interacts with the thiol group of GSH and isozymes have both a GSH-binding site (G-site) and a substrate-binding site (H-site) that facilitate catalysis through proton abstraction from GSH in proximity to the G-site (16). There is adequate evidence of genetic variation in humans. For example, Table 1 indicates the allelic variants associated with each family. The impact of GST polymorphisms on disease susceptibility and therapeutic outcomes has been extensively reviewed in the context of its Phase II detoxification properties. However, the role of these polymorphisms as mediators of S-glutathionylation or protein:protein interactions is less well studied. How these polymorphic variants influence cell functions or human health is still the subject of ongoing research and is discussed in more detail below.

Table 1.

Genetic Variations of Glutathione S-Transferase

| Allele | Nucleotide variability | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|

| GSTA1*A | Wild-type | 6 |

| GSTA1*B | Promoter point mutation | 6 |

| GSTA2*A | Pro110;Ser112;Lys196;Glu210 | 6 |

| GSTA2*B | Pro110;Ser112;Lys196;ALa210 | 6 |

| GSTA2*C | Pro110;Thr112;Lys196;Glu210 | 6 |

| GSTA2*D | Pro110;Ser112;Asn196;Glu210 | 6 |

| GSTA2*E | Ser110;Ser112;Lys196;Glu210 | 6 |

| GSTO1*A | Ala140;Glu155 | 10 |

| GSTO1*B | Ala140;Glu155 deletion | 10 |

| GSTO1*C | Asp140;Glu155 | 10 |

| GSTO1*D | Asp140;Glu155 deletion | 10 |

| GSTO2*A | Asn142 | 10 |

| GSTO2*B | Asp142 | 10 |

| GSTZ1*A | Lys32;Arg42;Thr82 | 14 |

| GSTZ1*B | Lys32;Gly42;Thr82 | 14 |

| GSTZ1*C | Glu32;Gly42;Thr82 | 14 |

| GSTZ1*D | Glu32;Gly42;Met82 | 14 |

| GSTM1*A | Lys173 | 1 |

| GSTM1*B | Asn173 | 1 |

| GSTM1*0 | Deletion | — |

| GSTM1*1×2 | Duplication | 1 |

| GSTM3*A | Wild type | 1 |

| GSTM3*B | 3 base deletion, intron 6 | 1 |

| GSTM4*A | Tyr2517 | 1 |

| GSTM4*B | T2517C frameshift | 1 |

| GSTT1*A | Thr104 | 22 |

| GSTT1*B | Pro104 | 22 |

| GSTT1*0 | Deletion | — |

| GSTT2*A | Met139 | 22 |

| GSTT2*B | Ile139 | 22 |

| GSTP1*A | Ile105;Ala114 | 11 |

| GSTP1*B | Val105;Ala114 | 11 |

| GSTP1*C | Val105;Val114 | 11 |

| GSTP1*D | Ile105;Val114 | 11 |

Overall cellular redox homeostasis is determined by the balance between oxidation and reduction reactions and plays an essential role in numerous signaling cascades, such as those associated with proliferation, inflammatory responses, apoptosis, and senescence. By nature of the high efficiency of oxygen-based intermediate metabolism, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) are invariable components of aerobic metabolism and key contributors to cellular redox. Cells can detect alterations in exogenous or endogenous oxidative conditions through a subset of cysteines in proteins. Precisely what constitutes redox sensing versus redox signaling (31) remains debatable, but cysteine residues at various oxidation states (emphasizing the importance of the variable valance states of sulfur) are at the center of the process. From an evolutionary standpoint, a correlation between organism cysteine content and degree of biological complexity appears to exist, implying that accumulation of sulfur amino acids may be relevant to evolutionary development (36). Since there are only around 200,000 cysteines encoded by the human genome (30), their functional importance may have assimilated as a consequence of strong positive selection pressure. Characteristic of the flexibility of the thiol group is that cysteine residues are among the most versatile amino acid acceptors to a variety of distinct types of post-translational modifications (31). For example, contingent upon the steric properties and localized environment of the cysteine, various oxidation states, thiol, disulfide, thiolate, sulfenic, sulfinic, or sulfonic acids; lipidation can occur through S-isoprenylation, S-farnesylation, S-geranylgeranylation, or S-palmitoylation; S-nitrosylation, S-cysteinylation, S-sulfhydration, S-acylation, S-thiohemiacetylation, and S-succinylation (9) have all been reported. As discussed below, some cysteine residues are susceptible to the post-translational modification of S-glutathionylation (i.e., the addition of GS.), altering the charge, structure, and/or function, and protein–protein interactions of a number of proteins that are classifiable in discrete clusters, including enzymes, receptors, structural proteins, transcription factors, and transport proteins. In contrast to recent reviews from our group (50, 58), the present forum article attempts to emphasize the roles that GST play in regulating cell survival/death pathways either directly or indirectly.

Detoxification

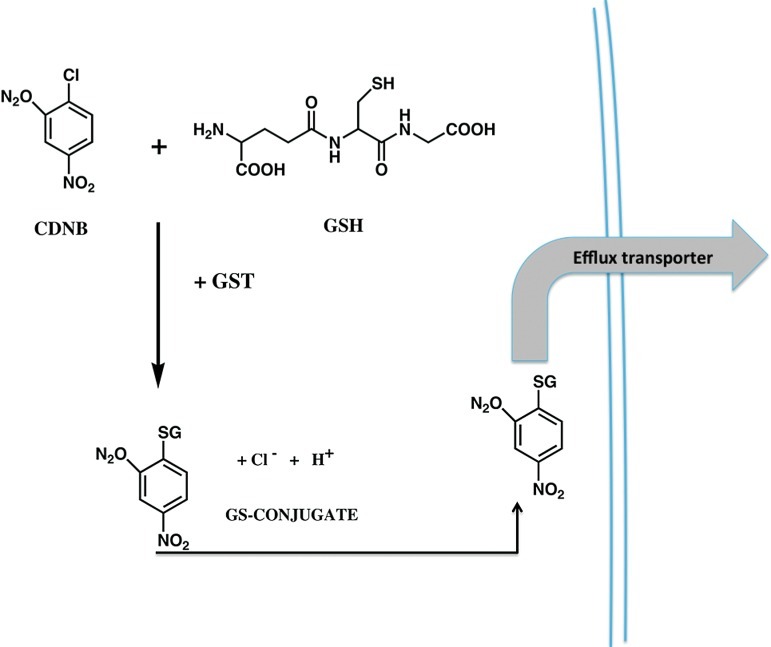

Since the earliest descriptions of GST (10) a multitude of reports have detailed their catalytic functions in conjugating GSH with a diverse range of electrophilic substrates. A generic example of the fate of a chemical electrophile is depicted in Figure 1. In the example shown, the conjugation of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) via GST occurs before efflux of the complex via the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCC1. This successfully removes the conjugated product from the cell milieu and negates any toxicity that may be associated with the residual product. Earlier studies also detailed the ligand-binding properties of GST (33) and recent indications are that both catalytic and protein:protein interactions are facilitated by GST family members. However, in the context of cell survival and death, obviously, broad-ranging detoxification reactions will have a significant impact upon the ability of a cell to survive externally mediated stress conditions. In most instances, an integrated and co-ordinated enhancement in the transcription of a battery of gene products may be best suited to the survival of a cell. From an energy-efficiency standpoint, there is merit in considering how cellular defense mechanisms may have evolved to ensure maximum chances of survival. For example, a specific investment of energy is required for each response promoted by external stimuli. Early in mammalian development, dietary and environmental toxins would have been a primary source of chemical threats. In evolving mechanisms to regulate Phase I and II detoxification programs, mammalian cells can either mount a specific, focused response where enhanced transcription and translation of one gene product suffices to detoxify, or co-ordinate a regulatory mechanism where a plurality of interacting protective products is mobilized. The latter would seem to have been preferred by nature. Perhaps, this is not surprising since the end result of inferior protection would be cell death, a process inconsistent with selective advantage. For the example shown in Figure 1, co-ordination of conjugation and efflux is critical to mounting a concerted detoxification response.

FIG. 1.

Detoxification scheme for glutathione conjugation. Scheme of detoxification of 1-chloro-2, 4-dinitrobenzene through catalytic thioether conjugate formation. Contingent upon the species and tissue efflux of this glutathione conjugate can be carried out by various transporters (32), including canalicular multispecific organic anion transporters and the ATP-binding cassette transporters, generally in the C family such as ABCC1. Co-ordinate regulation of genes is a frequent prerequisite for the full protective effects of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-mediated detoxification to be realized (39). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

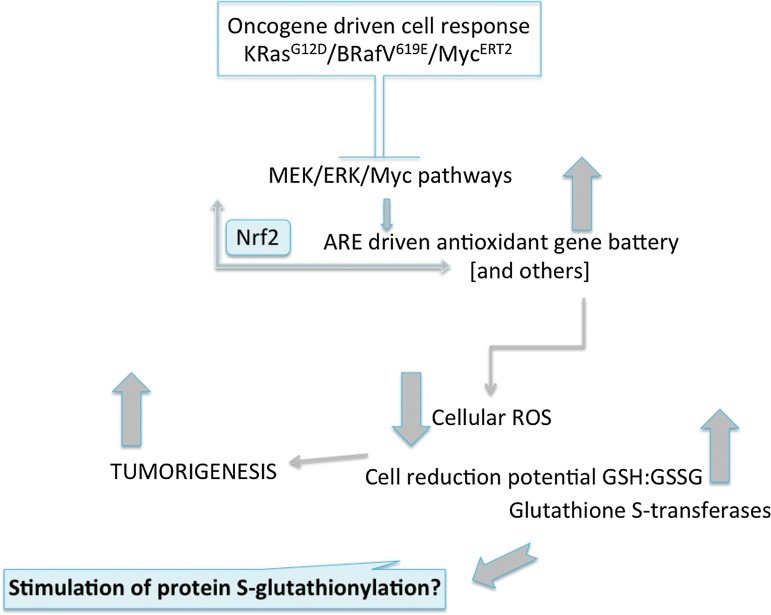

GSTs are among the genes regulated by the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2). This is one master switch in regulating the expression of a battery of stress response genes critical in mounting a cellular defense against electrophiles or ROS/RNS (26). Nrf2 is effective in promoting expression of genes that have one or more antioxidant response elements in their promoter regions. One domain of NRF2 negatively regulates its activity through protein:protein interactions with Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). Mammalian KEAP1 proteins are typically metalloproteins with between 25 and 27 conserved cysteines, essentially half of which are in basic regions and maintain the thiolate state under physiological conditions. Such cysteines fulfill the criteria required of redox sensors and in concert with NRF2 form the framework of the cellular response to ROS. They also provide a platform for the principles by which long-term exposure to low doses of inductive natural product (dietary) electrophiles can induce protective Phase II enzyme systems–chemoprevention. There are growing indications that this transcription factor complex may have an unusual role in tumorigenesis. For example, a recent study (13) showed that the conditional endogenous oncogenes K-RasG12D, B-RafV619E, and MycERT2 stably elevated basal Nrf2 through enhanced transcription, activating the platform of genes involved in the ROS response and lowering intracellular levels of ROS resulting in a more reduced intracellular environment. Oncogene-directed, increased expression of Nrf2 is a new mechanism for the activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant program and is evident in primary cells, tissues of mice expressing K-RasG12D and B-RafV619E, and in human pancreatic cancer cells (13). Furthermore, genetic targeting of the Nrf2 pathway impaired K-RasG12D-induced proliferation and tumorigenesis in vivo. Thus, the Nrf2 antioxidant and cellular detoxification program may in some way be a mediator of oncogenesis (see Fig. 2). In the context of GST, interpretation of these observations is likely contextual. For example, oncogenic signaling-mediated Nrf2 activation stimulates not only GST and the antioxidant battery, but also transporters, proteasome subunits, heat shock proteins, growth factors, and other Phase II-metabolizing gene products (26). Any or all of these could contribute to the oncogenic effects. GST are also contributors to the forward reaction of S-glutathionylation, and enzymes with catalytic cysteines (in particular, those involved with protein folding and stability, nitric oxide regulation, and redox homeostasis); cytoskeletal proteins; signaling proteins (particularly kinases and phosphatases); transcription factors; ras proteins; heat shock proteins; ion channels, calcium pumps, and binding proteins (involved in calcium homeostasis); energy metabolism and glycolysis (52). Alterations in the Nrf2 activity could shift the balance of GST involvement in the forward S-glutathionylation reaction, perhaps producing changes in post-translational patterns that could in turn promote proteins that regulate cell growth and division. Whatever the precise mechanism, regulation of redox homeostasis should be protective, but in a background of constitutively mutant Nrf2, the effects may become oncogenic (13).

FIG. 2.

Nrf2 and oncogenesis. Schematic of the involvement of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) regulation of redox gene batteries in oncogenic pathways. Certain oncogene-driven events can trigger kinase cascades in a manner that stimulates Nrf2-driven transcriptional upregulation of stress response gene batteries (including GST). In certain circumstances, this event has been shown to be pro-tumorigenic in nature (13), a process inconsistent with the presumed protective effects usually attributed to Nrf2 functions (26). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

Signal Transduction

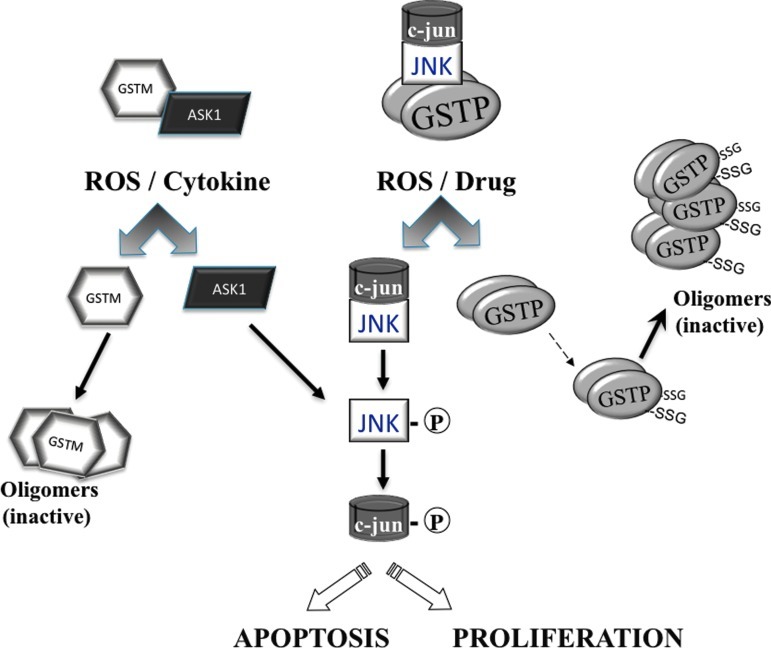

Jun-terminal kinases (JNKs) are a family of stress kinases subject to transient activation in response to ROS/RNS, heat or osmotic shock, and growth factors or inflammatory cytokines (12). Downstream events result in JNK-mediated phosphorylation of the transcription factors c-Jun, activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), p53, and ELK-1, directly contributing to the stress response through changes in the cell cycle, DNA repair, or apoptosis (12). The basal activity of JNK is necessarily maintained at a low level, and this is where GST functions as an endogenous negative regulatory switch for this kinase. As shown in Figure 3, glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP) has significant ligand-binding properties that manifest as a protein complex where JNK is regulated through protein:protein interactions. Studies on those factors/mechanisms responsible for the regulation of JNK before and immediately after ROS-mediated stress identified GSTP (1). Figure 3 illustrates how in nonstressed cells, low JNK activity is maintained as a consequence of sequestration of the kinase in a multiprotein complex that includes GSTP1-JNK. Following ROS or drug, GSTP1 dissociates from the complex, accumulating as GSTP oligomers with resultant activation of released JNK impacting subsequent downstream events, which in a cell or tissue specific manner can lead to events as divergent as proliferation or apoptosis (59). JNK-dependent stress-induced apoptosis may be suppressed during tumor development and in this regard, high levels of GSTP1 may serve the purpose of enhancing sequestration of JNK as inactive. This may account for the long observed phenomenon of elevated GSTP levels in drug-resistant tumor cells even when the selecting drug is not a direct substrate for GSH conjugation (49). Increased GSTP may be required to maintain the JNK activity at basal levels. Within the GST superfamily, ligand binding can be promiscuous and functional redundancies are common. The homology between GST A and P family members may explain why GSTA1 by a similar mechanism can also suppress JNK signaling caused by inflammatory cytokines or oxidative stress (42).

FIG. 3.

GSTP and JNK interactions. Scheme of the possible interactions between GST M and P isozymes and regulatory kinases and their disassociation following exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS), drugs, or cytokines. Other proteins in a stress-activated protein complexes are shown. See text for discussion of mechanistic implications. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

GSTP has also been implicated in regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) signaling through an association with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) (56). High GSTP levels inhibit TRAF2-induced activation of both JNK and p38, but not NFkB; attenuate TRAF2-enhanced apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) auto-phosphorylation and inhibit TRAF2-ASK1-induced apoptosis by suppressing the interaction of these two proteins. Obverse to this situation, reducing GSTP increased TNF-α-dependent TRAF2-ASK1 association, activating both ASK1 and JNK.

In each of the ligand interactions described, the catalytic activity of GSTP is not affected by protein binding, implying that the kinase effects are mediated at sites distant to those regions of GSTP involved in GSH or substrate binding.

A further example of functional redundancy within the GST family is afforded by the fact that GSTM1 can bind to and inhibit the activity of ASK1 (11). Similar to GSTP:JNK, the interaction of the GSTM1:ASK1 complex is dissociated under ROS, oligomerizing GSTM and leading to activation of ASK1 (Fig. 3) (17). Since ASK1 is a MAP kinase kinase kinase that activates the JNK and p38 pathways, this disassociation can be an upstream of cytokine- and stress-induced apoptosis (28). Altered expression of GSTM1 has been linked with an impaired clinical response to some tumor types and although not as commonly reported as GSTP, increased GSTM1 expression does occur in drug resistance. Moreover, GSTA1 suppresses activation of JNK signaling by a proinflammatory cytokine and oxidative stress and suggests a protective role for GSTA1-1 in JNK-associated apoptosis (42). In mouse hepatocytes, GSTA4 endogenous JNK and mGSTA4 co-immunoprecipitate and there is evidence that this isozyme can act as an endogenous regulator of JNK activity through direct binding (14). In each instance, GST function is likely not directly linked to detoxification, but may be supplanted and/or augmented by its role in kinase regulation (49). As a further extension of this principle, there are indications that GST involvement with the metabolism of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) may create an integral physiological role for the isozymes and their HNE products in the regulation of cell-signaling events (5).

GST Involvement in S-Glutathionylation

It is generally accepted that phosphorylation is a critical protein modification that influences cell signaling and survival pathways. In this context, there are numerous parallels between the processes of phosphorylation and S-glutathionylation. Some micro-organisms can thrive in the absence of phosphorus by substituting sulfur, making for example thiolipid instead of phospholipid membranes (2). S-glutathionylation of phosphatases (7) critical in maintaining the cyclical nature of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation permits an appreciation of how coalescing sulfur, and phosphorus biochemistry may contribute to critical regulatory pathways. Many proteins that are S-glutathionylated are also involved in growth regulatory pathways, including many kinases (51). Thus, in this context, the S-glutathionylation cycle may provide an additional layering of control of the phosphorylation cascades routinely regulated by kinases or phosphatases.

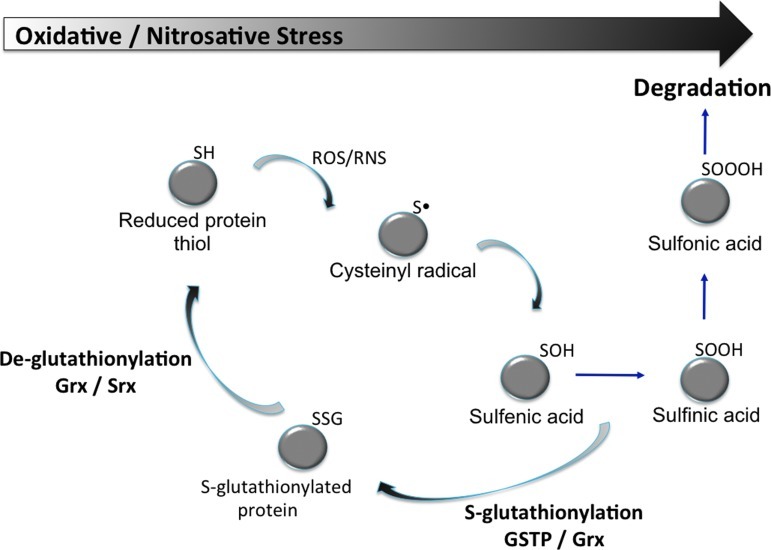

S-Glutathionylation can occur with cysteines in essentially basic environments within the protein (e.g., vicinal to Arg, His, or Lys residues) (Fig. 4). At physiological pH, GST can effectively lower the pKa of the cysteine thiol of GSH, resulting in formation of the nucleophilic thiolate anion (GS−) (23). Immediate delivery of an activated GSH may determine a particular catalytic or carrier GST function. Cysteines on the surfaces of globular proteins are exposed to GSH and GSSG and prone to spontaneous S-glutathionylation (22) and can be influenced by reducing/deglutathionylating enzymes such as thioredoxin (Trx) (4), glutaredoxin (Grx) (19), and sulfiredoxin (Srx) (20). In addition to its deglutathionylating function, Grx has also been shown to catalyze the oxidative modification of several proteins in the presence of a GS-radical generating system (45), implying that Grx is capable of catalyzing both the forward and reverse reactions via distinct mechanisms (57). Grx has a conserved two-cysteine residue motif (CXXC) where both cysteines are required for its reductive deglutathionylation function via a dithiol mechanism of disulfide exchange. However, studies with mutant Grx containing only the N-terminal cysteine residue within the conserved motif (CXXS) showed that Grx can also function as an oxidase through a monothiol mechanism. Grx can form a mixed disulfide (Grx-SG) as a consequence of both its oxidative and reductive mechanisms.

FIG. 4.

S-glutathionylation cycle. Representative steps in the S-glutathionylation cycle. In this simplified schema, the oxidation states of sulfur are represented progressively. However, cysteine oxidation by ROS can occur through either one- or two-electron pathways that might lead to simultaneous formation of cysteinyl radicals and/or sulfenic acids (54). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

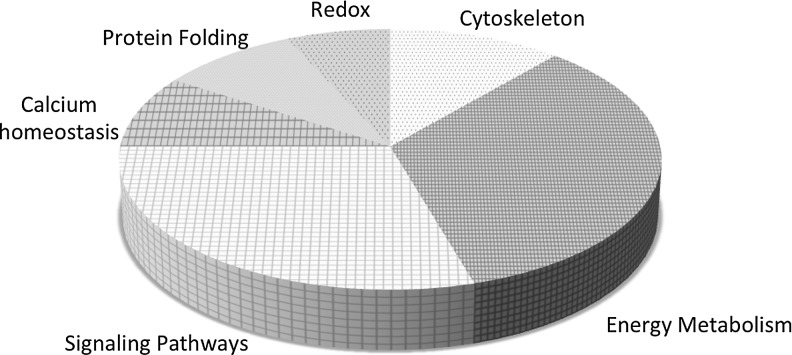

Relative to the proteome the actual number of S-glutathionylated proteins is not proportionally large and those sensitive to the post-translational modification tend to fall into clusters. Those categories of proteins thus far described as susceptible to S-glutathionylation are summarized in Figure 5 and include enzymes with catalytically important cysteines (in particular, those involved with protein folding and stability, nitric oxide regulation, and redox homeostasis); cytoskeletal proteins; signaling proteins—particularly kinases and phosphatases; transcription factors; ras proteins; heat shock proteins; ion channels, calcium pumps, and binding proteins (involved in calcium homeostasis); energy metabolism and glycolysis. In the majority of cases, these clusters represent protein families that have significant implications to cell survival pathways. Under stress-induced ROS or RNS, the half-life of S-glutathionylation approximates 4 h (52), although this value is both condition and cell specific. Ongoing and future research will help to establish the breadth and depth of the influence of this post-translational modification upon cell survival pathways.

FIG. 5.

Proteins subject to S-glutathionylation. This figure summarizes the clusters of proteins that have so far been identified as susceptible to S-glutathionylation.

GST Polymorphisms

As listed in Table 1 there are a number of polymorphic variants of each member of the GST family. This subject matter is highly represented in the epidemiological literature, but with little clear-cut clarity on the nature of the relationships between human populations, disease etiology, or response to therapies. At least for cancer, a number of reviews attempt to summarize the association between a phenotype and a disease response/progression (18). Moreover, there are a number of reviews that summarize the more mechanistic aspects of the importance of GSTP polymorphisms in cancer drug treatments. As shown in Table 1, polymorphic variants arise from nucleotide transitions that change, for example, codon 105 from Ile to Val and codon 114 from Ala to Val, generating four GSTP1 alleles: wild-type GSTP1*A (Ile105/Ala114), GSTP1*B (Val105/Ala114), GSTP1*C (Val105/Val114), and GSTP1*D (Ile105/Val114) (3). Although the Ile105→Val105 and Ala114→Val114 substitutions do not affect GSH-binding affinity, they do cause a steric change at the substrate-binding site of the enzyme impacting enzymatic activities of GSTP1B and GSTP1C. For CDNB, chlorambucil, and thiotepa, catalytic efficiency for thioether conjugation follows the pattern GSTP1A > GSTP1B > GSTP1C (41). However, in GSH conjugation of cis-platin, carboplatin, 4-hydroxyifosfamide, and diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, GSTP1C has the best catalytic constant (29). The hydrophobicity and size of residue 114 could serve as a determinant of the substrate specificity of each of the GSTP1 isozymes (27).

These types of analysis raise plausible issues about how individuals may respond to cancer therapies or to environmental stresses, the toxicities of which may be ameliorated by GSTP. Indeed, they form one of the cornerstones of individualized therapy, where for a cancer drug, reducing unnecessary side effects is a primary endeavor. Increased expression of GSTP1*A has been reported in cells that acquire resistance to cis-platin, reportedly through enhancing the formation of platinum– GSH conjugate formation (29). Individuals with the GSTP1*B allele (isoleucine to valine conversion) have substantially reduced catalytic activity correlating with a diminished potential to detoxify the drug. Additionally, homozygocity for GSTP1*B is linked with a diminished capacity to detoxify a number of platinum-based anticancer drugs (29). There is also early evidence that certain types of cancer may differentially express polymorphic variants. For example, GSTP1*C is an allelic variant predominant in malignant glioma (40). There is much need for continued elaboration of the importance of GST polymorphisms in correlative human population studies. Nevertheless, accurate epidemiological information should prove quite informative in determining whether genotyping for these polymorphisms will have practical application.

Viral Etiology

A recent study has unearthed a quite unusual property for GSTP in the context of viral evolution (35). An example of the Red Queen Effect where the pathogen (in this case human papilloma virus [HPV]-16) has coerced the human host cell GSTP to effect continued host cell survival even in the presence of infection, thereby maximizing transmission efficiency. For example, HPV-16 is thought to represent the causative agent for the majority of cervical carcinomas. HPV E6 and E7 are viral-specific genes that are usually expressed in these tumors, indicating an important role for their gene products (E6 and E7 oncoproteins) in inducing malignant transformation. These authors used protein:protein interaction methods to identify GSTP1 as a novel binding partner for the HPV E16 E7 oncoprotein. By engineering a mutant molecule of HPV-16 E7 with reduced affinity for GSTP1, they modified the equilibrium between the oxidized and reduced forms of GSTP1, inhibiting JNK phosphorylation and reduced its ability to induce apoptosis. Depletion of GSTP1 confirmed a pivotal role for GSTP1 in the prosurvival program elicited by its binding with HPV-16 E7, implicating a functional linkage between GSTP1 and the transforming abilities of this oncoprotein. Results obtained in cells expressing mutant HPV-16 E7 highlighted the role of its physical interaction with GSTP1 in modulating the anti-apoptotic, JNK-mediated activity and intimated a clear role for HPV-16 E7 in enhancing cell survival and provide additional evidence for the transforming capabilities of the E7 oncoprotein from high-risk HPVs. Such characteristics might facilitate selection of transformed cell clones causing cancer progression. In the context of the evolutionary significance, this shows an example of how continuing adaptation is required for a species to maintain its relative fitness among the systems with which it co-evolves.

Miscellaneous

The general importance of redox homeostasis in human disease is a research area of developing importance. Translational studies in a number of disparate subjects accentuate the broad relevance of the GSH/GST platform. A few of these are summarized in this section.

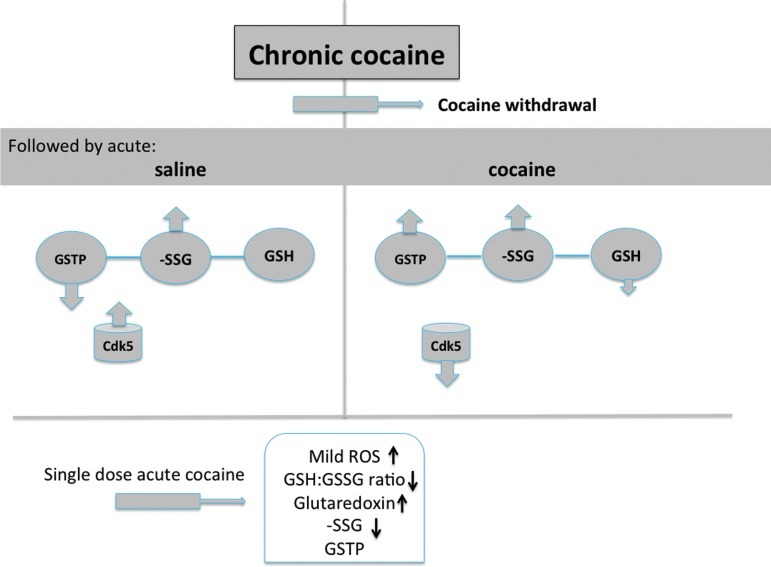

Disruption of redox homeostasis and imbalanced oxidative stress are hallmarks of a number of neurodegenerative diseases (6) and some recent trends in drug addiction focus on the importance of redox conditions in the brain. Daily cocaine administration was found to reduce GSH levels in the hippocampus and when restored, a normalization of cocaine-induced memory impairments was demonstrated (37). Acute cocaine overdose in mice elevates total GSH in the prefrontal cortex and striatum (53) and cocaine also causes elevated lipid peroxidation and superoxide dismutase levels in the brain (15) and cocaine relapse is linked with impaired glutamate homeostasis in the nucleus accumbens and results in part from cocaine-induced downregulation of the cystine–glutamate exchanger, which in turn is rate-limiting in the synthesis of GSH. Recent rodent studies showed that cocaine induced an increase in protein S-glutathionylation and a decrease in expression of GSTP (53). Using either pharmacological or genetic models of GSTP depletion, the capacity of cocaine to induce conditioned place preference or locomotor sensitization was augmented, indicating that reducing GSTP may contribute to cocaine-induced behavioral neuroplasticity. Conversely, an acute cocaine challenge after withdrawal from daily cocaine elicited a marked increase in accumbens GSTP and following inhibition of GSTP, the expression of behavioral sensitization to a further cocaine challenge injection was inhibited suggesting a protective effect by the acute cocaine-induced rise in GSTP. These type of results indicate that cocaine-induced oxidative stress induces changes in GSTP that contribute to cocaine-induced behavioral plasticity, a model for which is shown in Figure 6. A very recent report (46) showed that GSTP1 directly inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) by interfering with its interaction with p25/p35 and indirectly by eliminating oxidative stress. Cdk5 promotes and is activated by ROS, engaging a feedback loop ultimately leading to cell death. Under neurotoxic conditions, GSTP1 transduction conferred a high degree of neuroprotection, perhaps implying that GSTP1 levels may modulate Cdk5 signaling, eliminate oxidative stress, and prevent neurodegeneration. Interestingly, inhibition of Cdk5 also enhances cocaine self-administration (8), suggesting the existence of a nodal linkage between the kinase and its regulation by GSTP1 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

GSTP and cocaine addition. Model illustrating changes in GSTP, redox potential (GSH:GSSG), and protein S-glutathionylation (-SSG) in the rat nucleus accumbens after chronic cocaine addiction, withdrawal, and subsequent acute cocaine. In the absence of an acute cocaine challenge (saline), withdrawal from daily cocaine reduced GSTP and increased S-glutathionylation (-SSG), with only a minor impact redox potential. Following 45 min acute cocaine (right side of figure), the redox potential of the accumbens was altered, reflected by decreased GSH and increased GSSG, resulting in part from an increase in the flux of glutaredoxin-mediated protein deglutathionylation. In chronic cocaine animals, GSTP expression was increased following withdrawal, and subsequent acute cocaine, leading to a further increase in protein S-glutathionylation (increased -SSG). The increase in GSTP and Cys-SSG would cause lower GSH availability in the event of augmented oxidative stress, but may also lead to increased signaling via protein S-glutathionylation protecting cells from oxidative stress (51). In the chronic followed by acute cocaine group, enhanced GSTP could serve to inhibit Cdk5 activity, with consequences to the involvement of this kinase in cocaine addiction (46). In animals that were not previously addicted, 45 min after a single cocaine dose, elevated ROS and altered parameters of redox homeostasis were measurable, but no short term impact on GSTP was found (bottom of the figure). The model is adapted from data in reference (53). (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars).

The significance of GSTP-mediated S-glutathionylated targets after cocaine exposure is under investigation, along with the impact of polymorphisms that may relate to addiction. In this regard, cocaine dependence in a Brazilian population has been evaluated and it was shown that the Ile105 allele of GSTP may have an influence on the etiology of cocaine dependence (24).

A direct influence of GSTP on cell death is provided by the platform where GSTP is a target for drug discovery and development, particularly in cancer. This is based on the principle that high GSTP levels in solid tumors and drug-resistant cells will likely provide an advantageous target for optimizing therapeutic index (47). One such drug, TLK286 or Telcyta [γ-glutamyl-α-amino-β-(2-ethyl-N, N, N0, NO–tetrakis (2-chloroethyl) phosphorodiamidate)-sulfonyl-propionyl-(R)-(−)phenylglycine] is a lead clinical candidate where selective targeting of susceptible tumor phenotypes strategically results in release of a more active drug in tumor cells compared with normal tissue. Published preclinical studies have confirmed the mechanism of action of this drug (48), and despite some setbacks in early clinical trials, continued clinical testing is in progress. Perhaps, one of the limitations of these earlier trials was the absence of pharmacogenetic biomarkers in the protocol design. In the era of targeted individualized therapies for cancer, there is likely merit in identifying any correlations between GSTP1 levels and/or polymorphisms and patient response rates. At best these could help to establish a GST platform for the basis of pharmacogenetic or individualized therapy; at worst, the results may help to understand why certain patients do not respond to therapy. There are a number of candidate GST-targeted drugs at various stages of preclinical development and these are reviewed more comprehensively elsewhere (55). Consideration of genetic polymorphisms of GSTP could provide a more rational basis for their clinical testing, and protocol design might benefit from inclusion of such correlative analyses.

Recently, a linkage between thiols and redox and the importance of GST as a target in regulation of bone marrow cell proliferation has been considered. Long-term, self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have low levels of intracellular ROS and mice deficient in ROS-regulating genes have HSC that retain neither quiescence nor self-renewal capacities (38). Two distinct populations of HSC can be identified predicated on their baseline ROS. Those with low ROS retain self-renewal capabilities in serial transplantations, whereas this is diminished in high ROS HSC. Agents that impact redox homeostasis, particularly small molecule thiols, have been shown to influence myeloproliferation (50). Moreover, preclinical studies in mice with a peptidomimetic inhibitor of GSTP, [γ-glutamyl-S-(benzyl)-cysteinyl-R-(−) phenyl glycine diethyl ester], now named Telintra caused an increase in circulating blood cells of all lineages (44). This effect was noted in wild-type mice, but not in GSTP-deficient mice. Genetic ablation of GSTP caused a characteristic increase in myeloid cell differentiation and proliferation, evidenced by elevated numbers of circulating leukocytes. The agreement between genetic and pharmacological ablation of GSTP is consistent with the ability of Telintra to dissociate GSTP from JNK, allowing kinase phosphorylation, activation, and downstream myeloproliferation. Further downstream, the drug's myeloproliferative properties have been associated with activation of signal transduction and activators of transcription proteins in GSTP-deficient mice (21). Isozymes of the GSTA family are generally expressed at low levels in bone marrow, but their capacity to suppress activation of JNK signaling emphasizes the concept of GST promiscuity (42). In these circumstances, GSTP may also directly influence S-glutathionylation of a number of proteins involved in myeloproliferative events (such as JNK and SHP-1 and SHP-2). Any or all of these mechanistic properties could contribute to the myeloproliferative properties of Telintra, a drug presently in ongoing Phase 2 clinical trials for myelodysplastic syndrome.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The 20th century identified the enzyme catalysis/detoxification and ligand-binding (steroids, heme, bilirubin, and nitric oxide) properties of GST family members. Since the turn of the millennium, research has brought to bear additional biologically important roles ascribable to this isozyme family. For example, protein:protein interactions and possible chaperone activities; endogenous regulation of kinase pathways; catalysis of the forward reaction of the S-glutathionylation cycle; drug target linked with possible myeloproliferative properties; polymorphic variations may determine pharmacogentics and/or individual response to ROS/RNS or other stress events; involvement in some aspects of viral infections; and maintenance of cell viability. As our understanding appreciates, it seems likely that the biological importance of such a large and complex superfamily of genes with unusual overlapping and functional redundancies might continue to expand. Each new discovery will add to our understanding of how redox homeostasis influences human health.

Abbreviations Used

- ASK1

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase1

- ATF2

activating transcription factor 2

- CDNB

1-chloro-2, 4-dinitrobenzene

- Grx

glutaredoxin

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- GSTP

glutathione S-transferase P

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- HPV

human papilloma virus

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- KEAP1

Kelch like ECH-associated protein 1

- Nrf2

nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Srx

sulfiredoxin

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TRAF2

tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2

- Trx

thioredoxin

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA08660, CA117259, and NCRR P20RR024485) and support from the South Carolina Centers of Excellence program. This work was conducted in a facility constructed with the support from the National Institutes of Health, Grant Number C06 RR015455 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

References

- 1.Adler V. Yin Z. Fuchs SY. Benezra M. Rosario L. Tew KD. Pincus MR. Sardana M. Henderson CJ. Wolf CR. Davis RJ. Ronai Z. Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J. 1999;18:1321–1334. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcaraz LD. Olmedo G. Bonilla G. Cerritos R. Hernandez G. Cruz A. Ramirez E. Putonti C. Jimenez B. Martinez E. Lopez V. Arvizu JL. Ayala F. Razo F. Caballero J. Siefert J. Eguiarte L. Vielle JP. Martinez O. Souza V. Herrera-Estrella A. Herrera-Estrella L. The genome of Bacillus coahuilensis reveals adaptations essential for survival in the relic of an ancient marine environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5803–5808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800981105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali-Osman F. Akande O. Antoun G. Mao JX. Buolamwini J. Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of full-length cDNAs of three human glutathione S-transferase Pi gene variants. Evidence for differential catalytic activity of the encoded proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10004–10012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arner ES. Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem/FEBS. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awasthi YC. Ansari GA. Awasthi S. Regulation of 4-hydroxynonenal mediated signaling by glutathione S-transferases. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:379–407. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnham KJ. Masters CL. Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett WC. DeGnore JP. Konig S. Fales HM. Keng YF. Zhang ZY. Yim MB. Chock PB. Regulation of PTP1B via glutathionylation of the active site cysteine 215. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6699–6705. doi: 10.1021/bi990240v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benavides DR. Quinn JJ. Zhong P. Hawasli AH. DiLeone RJ. Kansy JW. Olausson P. Yan Z. Taylor JR. Bibb JA. Cdk5 modulates cocaine reward, motivation, and striatal neuron excitability. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2007;27:12967–12976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4061-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blatnik M. Frizzell N. Thorpe SR. Baynes JW. Inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase by fumarate in diabetes: formation of S-(2-succinyl)cysteine, a novel chemical modification of protein and possible biomarker of mitochondrial stress. Diabetes. 2008;57:41–49. doi: 10.2337/db07-0838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyland E. Chasseaud LF. Glutathione S-aralkyltransferase. Biochem J. 1969;115:985–991. doi: 10.1042/bj1150985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SG. Lee YH. Park HS. Ryoo K. Kang KW. Park J. Eom SJ. Kim MJ. Chang TS. Choi SY. Shim J. Kim Y. Dong MS. Lee MJ. Kim SG. Ichijo H. Choi EJ. Glutathione S-transferase mu modulates the stress-activated signals by suppressing apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12749–12755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis RJ. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeNicola GM. Karreth FA. Humpton TJ. Gopinathan A. Wei C. Frese K. Mangal D. Yu KH. Yeo CJ. Calhoun ES. Scrimieri F. Winter JM. Hruban RH. Iacobuzio-Donahue C. Kern SE. Blair IA. Tuveson DA. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desmots F. Loyer P. Rissel M. Guillouzo A. Morel F. Activation of C-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for glutathione transferase A4 induction during oxidative stress, not during cell proliferation, in mouse hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5691–5696. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietrich JB. Mangeol A. Revel MO. Burgun C. Aunis D. Zwiller J. Acute or repeated cocaine administration generates reactive oxygen species and induces antioxidant enzyme activity in dopaminergic rat brain structures. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirr H. Reinemer P. Huber R. X-ray crystal structures of cytosolic glutathione S-transferases. Implications for protein architecture, substrate recognition and catalytic function. Eur J Biochem/FEBS. 1994;220:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorion S. Lambert H. Landry J. Activation of the p38 signaling pathway by heat shock involves the dissociation of glutathione S-transferase Mu from Ask1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30792–30797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekhart C. Rodenhuis S. Smits PH. Beijnen JH. Huitema AD. An overview of the relations between polymorphisms in drug metabolising enzymes and drug transporters and survival after cancer drug treatment. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes AP. Holmgren A. Glutaredoxins: glutathione-dependent redox enzymes with functions far beyond a simple thioredoxin backup system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:63–74. doi: 10.1089/152308604771978354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Findlay VJ. Townsend DM. Morris TE. Fraser JP. He L. Tew KD. A novel role for human sulfiredoxin in the reversal of glutathionylation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6800–6806. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gate L. Majumdar RS. Lunk A. Tew KD. Increased myeloproliferation in glutathione S-transferase pi-deficient mice is associated with a deregulation of JNK and Janus kinase/STAT pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8608–8616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghezzi P. Regulation of protein function by glutathionylation. Free Radic Res. 2005;39:573–580. doi: 10.1080/10715760500072172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graminski GF. Kubo Y. Armstrong RN. Spectroscopic and kinetic evidence for the thiolate anion of glutathione at the active site of glutathione S-transferase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3562–3568. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guindalini C. O'Gara C. Laranjeira R. Collier D. Castelo A. Vallada H. Breen G. A GSTP1 functional variant associated with cocaine dependence in a Brazilian population. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2005;15:891–893. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes JD. Flanagan JU. Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes JD. McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu X. Xia H. Srivastava SK. Pal A. Awasthi YC. Zimniak P. Singh SV. Catalytic efficiencies of allelic variants of human glutathione S-transferase P1-1 toward carcinogenic anti-diol epoxides of benzo[c]phenanthrene and benzo[g]chrysene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5340–5343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ichijo H. Nishida E. Irie K. ten Dijke P. Saitoh M. Moriguchi T. Takagi M. Matsumoto K. Miyazono K. Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishimoto TM. Ali-Osman F. Allelic variants of the human glutathione S-transferase P1 gene confer differential cytoprotection against anticancer agents in Escherichia coli. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:543–553. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones DP. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C849–C868. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones DP. Redox sensing: orthogonal control in cell cycle and apoptosis signalling. J Intern Med. 2010;268:432–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keppler D. Export pumps for glutathione S-conjugates. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:985–991. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Litwack G. Ketterer B. Arias IM. Ligandin: a hepatic protein which binds steroids, bilirubin, carcinogens and a number of exogenous organic anions. Nature. 1971;234:466–467. doi: 10.1038/234466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannervik B. Danielson UH. Glutathione transferases—structure and catalytic activity. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1988;23:283–337. doi: 10.3109/10409238809088226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mileo AM. Abbruzzese C. Mattarocci S. Bellacchio E. Pisano P. Federico A. Maresca V. Picardo M. Giorgi A. Maras B. Schinina ME. Paggi MG. Human papillomavirus-16 E7 interacts with glutathione S-transferase P1 and enhances its role in cell survival. PloS One. 2009;4:e7254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miseta A. Csutora P. Relationship between the occurrence of cysteine in proteins and the complexity of organisms. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1232–1239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muriach M. Lopez-Pedrajas R. Barcia JM. Sanchez-Villarejo MV. Almansa I. Romero FJ. Cocaine causes memory and learning impairments in rats: involvement of nuclear factor kappa B and oxidative stress, and prevention by topiramate. J Neurochem. 2010;114:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naka K. Muraguchi T. Hoshii T. Hirao A. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and genomic stability in hematopoietic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1883–1894. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Brien M. Kruh GD. Tew KD. The influence of coordinate overexpression of glutathione phase II detoxification gene products on drug resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2000;294:480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okcu MF. Selvan M. Wang LE. Stout L. Erana R. Airewele G. Adatto P. Hess K. Ali-Osman F. Groves M. Yung AW. Levin VA. Wei Q. Bondy M. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms and survival in primary malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2004;10:2618–2625. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandya U. Srivastava SK. Singhal SS. Pal A. Awasthi S. Zimniak P. Awasthi YC. Singh SV. Activity of allelic variants of Pi class human glutathione S-transferase toward chlorambucil. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:258–262. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero L. Andrews K. Ng L. O'Rourke K. Maslen A. Kirby G. Human GSTA1-1 reduces c-Jun N-terminal kinase signalling and apoptosis in Caco-2 cells. Biochem J. 2006;400:135–141. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.This reference has been deleted

- 44.Ruscoe JE. Rosario LA. Wang T. Gate L. Arifoglu P. Wolf CR. Henderson CJ. Ronai Z. Tew KD. Pharmacologic or genetic manipulation of glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GSTpi) influences cell proliferation pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Starke DW. Chock PB. Mieyal JJ. Glutathione-thiyl radical scavenging and transferase properties of human glutaredoxin (thioltransferase). Potential role in redox signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14607–14613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun KH. Chang KH. Clawson S. Ghosh S. Mirzaei H. Regnier F. Shah K. Glutathione-S-transferase P1 is a critical regulator of Cdk5 kinase activity. J Neurochem. 2011;118:902–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tew KD. Glutathione-associated enzymes in anticancer drug resistance. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4313–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tew KD. TLK-286: a novel glutathione S-transferase-activated prodrug. Exp Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:1047–1054. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tew KD. Redox in redux: emergent roles for glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP) in regulation of cell signaling and S-glutathionylation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tew KD. Manevich Y. Grek C. Xiong Y. Uys J. Townsend DM. The role of glutathione S-transferase P in signaling pathways and S-glutathionylation in cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Townsend DM. S-glutathionylation: indicator of cell stress and regulator of the unfolded protein response. Mol Interv. 2007;7:313–324. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.6.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Townsend DM. Manevich Y. He L. Hutchens S. Pazoles CJ. Tew KD. Novel role for glutathione S-transferase pi. Regulator of protein S-glutathionylation following oxidative and nitrosative stress. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:436–445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805586200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uys JD. Knackstedt L. Hurt P. Tew KD. Manevich Y. Hutchens S. Townsend DM. Kalivas PW. Cocaine-induced adaptations in cellular redox balance contributes to enduring behavioral plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacolgy. 2011;36:2551–2560. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winterbourn CC. Hampton MB. Thiol chemistry and specificity in redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wondrak GT. Redox-directed cancer therapeutics: molecular mechanisms and opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:3013–3069. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu Y. Fan Y. Xue B. Luo L. Shen J. Zhang S. Jiang Y. Yin Z. Human glutathione S-transferase P1-1 interacts with TRAF2 and regulates TRAF2-ASK1 signals. Oncogene. 2006;25:5787–5800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiao R. Lundstrom-Ljung J. Holmgren A. Gilbert HF. Catalysis of thiol/disulfide exchange. Glutaredoxin 1 and protein-disulfide isomerase use different mechanisms to enhance oxidase and reductase activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21099–21106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiong Y. Uys JD. Tew KD. Townsend DM. S-glutathionylation: from molecular mechanisms to health outcomes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:233–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yin Z. Ivanov VN. Habelhah H. Tew K. Ronai Z. Glutathione S-transferase p elicits protection against H2O2-induced cell death via coordinated regulation of stress kinases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4053–4057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]