Abstract

Although waist circumference (WC) is a marker of visceral adipose tissue (VAT), WC cut-points are based on BMI category. We compared WC–BMI and WC–VAT relationships in blacks and whites. Combining data from five studies, BMI and WC were measured in 1,409 premenopausal women (148 white South Africans, 607 African–Americans, 186 black South Africans, 445 West Africans, 23 black Africans living in United States). In three of five studies, participants had VAT measured by computerized tomography (n = 456). Compared to whites, blacks had higher BMI (29.6 ± 7.6 (mean ± s.d.) vs. 27.6 ± 6.6 kg/m2, P = 0.001), similar WC (92 ± 16 vs. 90 ± 15 cm, P = 0.27) and lower VAT (64 ± 42 vs. 101 ± 59 cm2, P < 0.001). The WC–BMI relationship did not differ by race (blacks: β (s.e.) WC = 0.42 (.01), whites: β (s.e.) WC = 0.40 (0.01), P = 0.73). The WC–VAT relationship was different in blacks and whites (blacks: β (s.e.) WC = 1.38 (0.11), whites: β (s.e.) WC = 3.18 (0.21), P < 0.001). Whites had a greater increase in VAT per unit increase in WC. WC–BMI and WC–VAT relationships did not differ among black populations. As WC–BMI relationship did not differ by race, the same BMI-based WC guidelines may be appropriate for black and white women. However, if WC is defined by VAT, race-specific WC thresholds are required.

Waist circumference (WC) is used independently and as a component of the metabolic syndrome to predict cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (1). Since body fat distribution is different between blacks and whites (2, 3) and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and even hypertension and obesity is higher in blacks than whites, the WC of risk may not be the same in blacks and whites (4, 5) Yet due to a lack of data in blacks, it is the practice of the International Diabetes Federation, World Health Organization, American Heart Association, and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to use WC cut-points determined in whites to also predict risk for blacks (1).

The debate on whether the WC of risk should be based on the relationship between WC and BMI (WC–BMI) or WC and visceral adipose tissue (WC–VAT), presents another challenge in identifying the WC of risk (1, 6, 7). International Diabetes Federation, World Health Organization, American Heart Association, and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute rely on the WC–BMI relationship (1). Yet in blacks and whites, VAT is etiologically related to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation; all features of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome (6, 8, 9). Consequently, strong support exists for transitioning the WC of risk from the WC–BMI relationship to the WC–VAT relationship (6).

Studies in the United States and South Africa have established that the WC–VAT relationship is different between blacks and whites (American whites vs. African Americans and South African Whites vs. South African blacks) (2, 3), but the WC–VAT relationship has never been compared among black populations (i.e., African Americans vs. African blacks). In addition, the extent of variation by either race or black ancestry in the WC–BMI relationship is unknown.

By combining data from five studies performed in four research centers: the University of Cape Town (Cape Town, South Africa), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center (Bethesda, MD), the Howard University Family Study (Washington, DC) and the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus Study (five urban centers in Nigeria and Ghana), we had the opportunity to compare the WC–BMI relationship and WC–VAT relationship in white South African women and four groups of black women: black South Africans, African Americans, West Africans, and black Africans living in the United States (3, 10-12). In black and white women, our goal was to analyze WC–BMI and WC–VAT relationships to determine whether a black–white difference exists or if variation among the four groups of black women occurs.

Methods

The subjects were 1,409 unrelated, nondiabetic women, age range 18-50 years, BMI range 18.5–55.0 kg/m2, WC range 60–155 cm. All were participants in one of five studies designed to understand insulin resistance, body composition, fat metabolism or risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease. The number of women in each group was: white South African (n = 148), African American (n = 607), black South African (n = 186), West African (n = 445), and black Africans living in the United States (n = 23). The black African women living in the United States were born in West Africa (65%), Central Africa (30%), and East Africa (5%). Although the number of black Africans living in the United States was small, they were included because they represent a geographically diverse group. Women known to have human immunodeficiency virus were not enrolled in any of the five studies.

The South African women were enrolled in protocols at the University of Cape Town (3). The African Americans were participants in protocols at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD or the Howard University Family Study (10, 12-15). As there was no statistical difference in any variable under investigation, the African Americans from NIH and Howard University were analyzed together. The West Africans were residents of cities in either Nigeria or Ghana and were enrolled in the Africa America Diabetes Mellitus Study (11, 16). The Black Africans living in the United States were studied at NIH. All protocols were approved by the institutional review board at NIH or the institutional review boards of the participating universities. All subjects gave informed consent.

At all sites, weight was determined with calibrated scales and height by stadiometer. The level of precision for weight was ±0.1 kg and height was ±0.1 cm. At all sites WC was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. WC was measured once in the South African women. WC from the other sites is reported as the mean of two or three determinations. The coefficient of variation for measurement of WC was <2%. WC was measured at the umbilicus in the South Africans, at the iliac crest in the participants from NIH and at the minimum waist in women enrolled in the Howard University Family Study and Africa America Diabetes Mellitus.

As the women in Howard University Family Study and Africa America Diabetes Mellitus did not have computerized tomographic (CT) scans performed, they were not included in the analyses of the WC–VAT relationship. All women from the other studies had abdominal CT scans (n = 456). The South African women had VAT area measured with a single slice CT at L4–5 (Toshiba Xpress Helical Scanner; Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). The African-American women had VAT measured at both L2–3 and L4–5 using a HiSpeed Advantage CT/I scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and analyzed on a SUN workstation using the MEDx image analysis software package (Sensor System, Sterling, VA). Previous work has shown no significant difference in the VAT results obtained from measurements at L2–3 and L4–5 (13). The black Africans living in the United States had single slice CT at L2–3. At the South African site and NIH, the level of precision for VAT measurements was ±0.01 cm2. All CT scans in the African American and black African women living in the United States were read twice and the coefficient of variation <2%.

statistical analyses

Comparisons were by unpaired t-tests or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. Multiple regression analysis was performed with WC as the independent variable and either BMI (natural log transformed) or VAT as dependent variables. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed with STATA, version 10 (Stata, College Station, TX).

Results

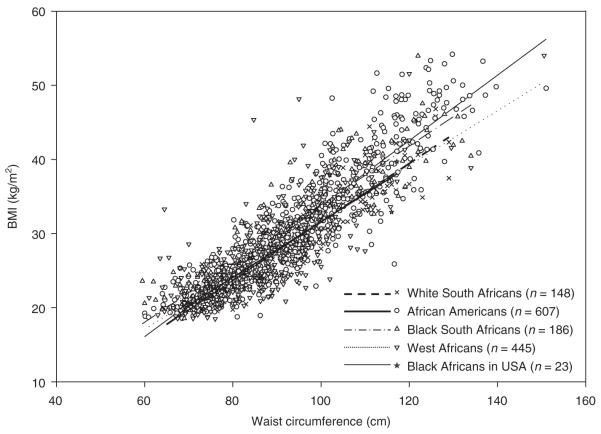

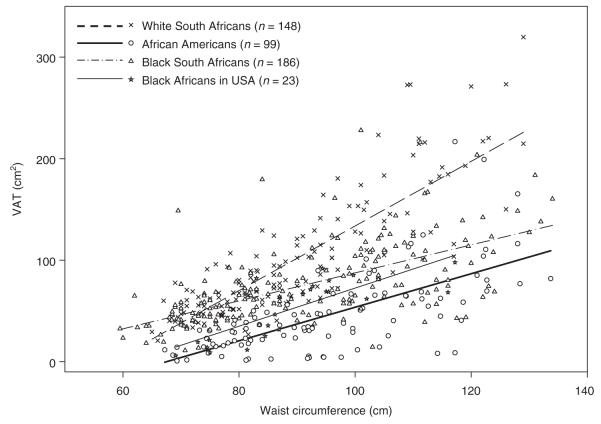

WC, BMI, and VAT for the participants are provided in Supplementary Table S1 online. The relationship of WC to BMI did not differ by race (blacks: R2 = 0.78, β (s.e.) WC = 0.42 (0.01), whites: R2 = 0.85, β (s.e.) WC 0.40 (0.01), P = 0.18) or among the four groups of black women (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S2 online). The relationship of WC to VAT was different by race (blacks: R2 = 0.33, β (s.e.) WC: 1.38 (0.11), whites: R2 = 0.69, β (s.e.) WC: 3.18 (0.21), P < 0.001). The increase in VAT per unit increase in WC was greater in white than black women. However, the WC–VAT relationship was not different in the African Americans, black South Africans, and black Africans in the United States (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S3 online).

Figure 1.

BMI vs. waist circumference: scatter plots and linear regression line for each group. Equations for white South Africans: BMI = −7.9 + 0.39 WC; African Americans: BMI = −10.4 + 0.44 WC; black South Africans: BMI = −5.7 + 0.40 WC; West Africans: BMI = −5.0 + 0.37 WC; black Africans in United States: BMI = −6.0 + 0.38 WC. WC, waist circumference.

Figure 2.

Visceral adipose tissue vs. waist circumference: scatter plots and linear regression line for each group. Equations for white South Africans: VAT = −185 + 3.18 WC; African Americans: VAT = −111 + 1.65 WC; black South Africans: VAT = −50 + 1.38 WC; black Africans in United States: VAT = −115 + 1.88 WC. VAT, visceral adipose tissue; WC, waist circumference.

discussion

This combined analysis of five studies is the largest comparison ever reported of the WC–BMI relationship and the WC–VAT relationship in women from Africa and the diaspora. We found no difference in the WC–BMI relationship (the basis for the International Diabetes Federation and American Heart Association/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute guidelines for WCs) in the four groups of women of African descent included in this study or between the white and black women. Based on these data, if there is a consensus that the BMI of risk is the same for black and white women, the same WC may be appropriate in both groups.

In addition, we report that the WC–VAT relationship is similar in African Americans, black South Africans and black Africans living in the United States. Therefore, if the WC–VAT relationship becomes the focus for the diagnosis of central obesity, our data suggest that WC cut-offs may be the same for black women irrespective of geographical location. We also report that the WC–VAT relationship was equally different between the white women and each of the three groups of black women that had CT scans. Therefore, if the WC–VAT relationship is the important determinant of central obesity, WC thresholds will be different in black and white women.

As data from five studies were combined, differences in measurement techniques are expected. For the WC–BMI analyses, WC was measured at three different sites, umbilicus, iliac crest, and minimum waist. However, the difference in WC site is mitigated by the sample size and the high prevalence of obesity among the participants (41%). With increasing obesity, landmarks become progressively more difficult to define, and consequently, the difference in WC measurement technique is less relevant. In addition, even BMI measurements would be different across studies, because equipment used to measure weight and height would vary. Nevertheless, even with the differences inherent in post hoc combined analyses, the WC–BMI relationship was similar in the five groups of women enrolled and this is testimony to the robustness of the observation. For the WC–VAT analyses, VAT determinations were performed in three studies on two different types of CT scanners. In addition, 95% of the women had VAT measured at L4–5 and 5% at L2–3. Again, even with these differences the relationship between WC and VAT was similar within the black populations and equally different between blacks and whites. Lastly, only premenopausal women in the age range of 18–50 years were analyzed. Therefore our conclusions may not be relevant to men or older or younger women.

This combined analysis of several studies was designed to provide data on the WC–BMI and WC–VAT relationships in women of African descent, and between black and white populations.

We believe that ultimately, guidelines on the WC of risk should be based on prospective studies. Until that data is available, if WC guidelines are based primarily on the relationship of WC to BMI, then the same WC thresholds may be appropriate for black and white women. However, if the WC of risk is based on the WC–VAT relationship, then race-specific WC thresholds are necessary.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.E.S., A.V.T., and M.R. were supported by the intramural program of NIDDK, NIH. C.N.R. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the center for Research in Genomics and Global health, NhGRI, NIh. The hUFS was supported by grant S06GM008016-320107. african american enrollment was carried out at the General clinical Research center supported by NcRR grant 2M01RR010284 and the National human Genome center at howard University. The aaDM study was supported by grants obtained from NcMhD, NhGRI, and NIDDK. Symington Radiology is acknowledged for performing the South african scans. The South african study was funded by the South african Medical Research council, the International atomic Energy agency, the National Research Foundation of South africa, and the University of cape Town. The authors thank Ms. Ugochi J. Ukegbu for her careful review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/oby

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katzmarzyk PT, Bray GA, Greenway FL, et al. Racial differences in abdominal depot-specific adiposity in white and African American adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:7–15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Micklesfield LK, Evans J, Norris SA, et al. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and anthropometric estimates of visceral fat in Black and White South African Women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:619–624. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–1268. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Després JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006;444:881–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jennings CL, Lambert EV, Collins M, et al. Determinants of insulin-resistant phenotypes in normal-weight and obese Black African women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1602–1609. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings CL, Lambert EV, Collins M, Levitt NS, Goedecke JH. The atypical presentation of the metabolic syndrome components in black African women: the relationship with insulin resistance and the influence of regional adipose tissue distribution. Metab Clin Exp. 2009;58:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, et al. A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotimi CN, Dunston GM, Berg K, et al. In search of susceptibility genes for type 2 diabetes in West Africa: the design and results of the first phase of the AADM study. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumner AE, Sen S, Ricks M, et al. Determining the waist circumference in african americans which best predicts insulin resistance. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:841–846. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumner AE, Farmer NM, Tulloch-Reid MK, et al. Sex differences in visceral adipose tissue volume among African Americans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:975–979. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumner AE, Finley KB, Genovese DJ, Criqui MH, Boston RC. Fasting triglyceride and the triglyceride-HDL cholesterol ratio are not markers of insulin resistance in African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1395–1400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulloch-Reid MK, Hanson RL, Sebring NG, et al. Both subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue correlate highly with insulin resistance in african americans. Obes Res. 2004;12:1352–1359. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oli JM, Adeyemo AA, Okafor GO, et al. Basal insulin resistance and secretion in Nigerians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:595–599. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.