Abstract

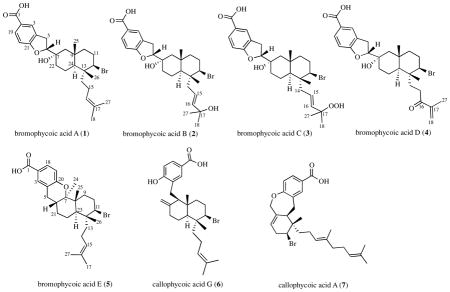

Bioassay-guided fractionation of extracts from a Fijian red alga in the genus Callophycus resulted in the isolation of five new compounds of the diterpene-benzoate class. Bromophycoic acids A-E (1–5) were characterized by NMR and mass spectroscopic analyses and represent two novel carbon skeletons, one with an unusual proposed biosynthesis. These compounds display a range of activities against human tumor cell lines, malarial parasite, and bacterial pathogens including low micromolar suppression of MRSA and VREF.

INTRODUCTION

Chemical investigations of red algae belonging to the order Gigartinales have revealed many secondary metabolites typical of red algae, such as halogenated phenolics and indoles, halogenated monoterpenes, and sulfated polysaccharides. However, structurally complex bioactive natural products from this order of seaweeds are rare, and include the bromophycolides, callophycols, and callophycoic acids, many of which show promising activity against the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. These compounds have contributed nine new carbon skeletons to the natural products literature since 2005.1–5

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Morphological examination of formalin-preserved samples of Fijian red alga collection G-0807 indicated a Callophycus species (G. Kraft, University of Melbourne, pers. comm.). Our previous studies focused on C. serratus and C. densus from Fiji,1–5 the two differing morphologically, genetically, and chemically. C. densus has thinner, flatter blades, occasionally with pale tips, and has more finely and evenly toothed, regular serrations, whereas C. serratus is thicker, darker, with a more prominent central midrib, more coarsely and less regularly spaced, often compound, lateral serrations, and does not lie as flat.6 Genetic analysis has indicated only small (approx. 1%) differences in 18S rRNA sequence between C. serratus and C. densus.7 These morphological and genetic differences have tracked consistently with secondary metabolite composition among these two species collected in Fiji, with C. serratus producing macrocyclic diterpene-shikimate bromophycolides and C. densus producing non-macrocyclic diterpene-shikimate callophycoic acids and callophycols.7

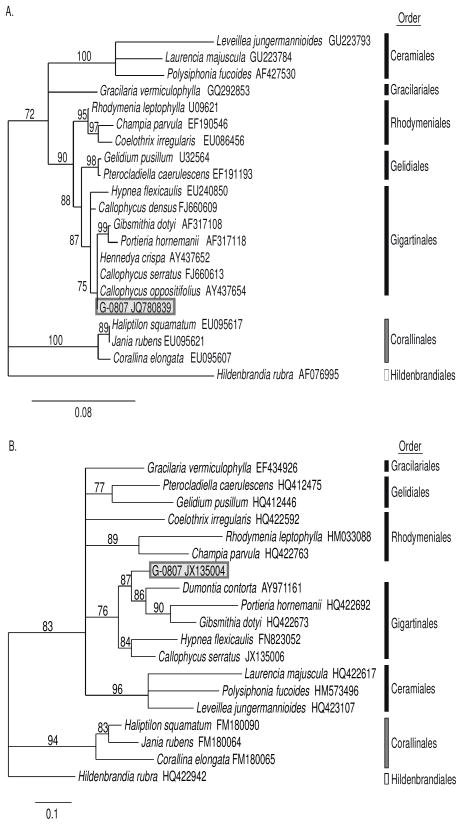

The current red algal sample G-0807 shared morphological traits with C. serratus, but in the absence of cystocarpic material it was not possible to make a positive identification. Amplification and sequencing of the nuclear small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) and the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) genes yielded 1640 base pair (bp) and 491 bp sequences, respectively. E-values and maximum scores of both 18S rRNA and COI genes from BLAST queries in GenBank revealed high similarity to multiple taxa within the order Gigartinales, of which Callophycus is a member (SI). Maximum sequence similarity between G-0807 and previously reported species belonging to the order Gigartinales was 99% and 89% (18S rRNA and COI, respectively). Independent phylogenetic analyses of G-0807 18S rRNA and COI revealed the highly supported relationship of G-0807 to representatives of the order Gigartinales obtained from GenBank (Figure 1). Overall, morphological and phylogenetic analyses are consistent with identification of G-0807 as a member of the genus Callophycus; however, this sample is genetically distinct from Callophycus species (including C. serratus and C. densus) represented in GenBank, and exhibits differences in secondary metabolism compared to C. serratus and C. densus, as revealed below.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of Fijian red alga Callophycus sp. (collection G-0807) within the class Florideophyceae based on maximum likelihood criteria from A) small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) and B) cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) genes. Black bars indicate representatives of the subclass Rhodymeniophycidae, grey bars are Corallinophycidae and white bars are Hildenbrandiophycidae. Values (%) on branches indicate bootstrap support after 1000 iterations (only values >70% are shown).

Extracts of Callophycus sp. collection G-0807 yielded five novel natural products, bromophycoic acids A-E (1–5). HRESI-MS analysis of 1 displayed an [M-H]− with m/z 503.1797, suggesting a molecular formula of C27H37BrO4 with nine degrees of unsaturation. The presence of a single bromine atom was confirmed by a second parent ion of similar intensity at m/z 505. Comparison of NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1 and SI) with published data revealed many structural similarities to the callophycoic acids previously characterized from C. densus3, including the presence of the same 1,3,4-trisubstitued phenyl moiety in 1. A strong IR absorption corresponding to a C=O stretch (vmax1684 cm−1) and weaker band corresponding to an OH (vmax 3535 cm−1) confirmed the presence of a carboxylic acid.8 HMBC correlations from both H5 (δ 3.07, 3.22) to aromatic quaternary C4 (δ 128.4), from H5b to carbinol methine C6 (δ 86.1), and from H6 (δ 5.13) to oxygenated quaternary C7 (δ 71.0) established the tail of the diterpene substituent attached to position C4 on the aromatic ring. COSY correlations between both H5 and H6 established the order as C4-C5-C6-C7. An HMBC correlation of H6 to phenoxy C21 (δ 163.6) established the 2,3-dihydrofuran structure.

Table 1.

13C and 1H NMR spectroscopic data for bromophycoic acids A-E (1–5) (500 MHz; in DMSO-d6 for 1–4; in CDCl3 for 5). 13C NMR chemical shifts for 2 and 4 were inferred by DEPT-135, HSQC, and HMBC experiments rather than by 13C NMR spectra.

| 1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | δC | δH, (JH,H) | δC | δH, (JH,H) | δC | δH, (JH,H) | δC | δH, (JH,H) | δC | δH, (JH,H) | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 1 | 167.3 | 167.5 | 167.6 | 167.5 | 170.7 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 122.6 | 123.2 | 124.5 | 124.2 | 120.2 | ||||||||||

| 3 | 126.1 | 7.72 | s | 126.1 | 7.71 | s | 125.9 | 7.70 | s | 126.0 | 7.70 | s | 132.3 | 7.82 | s |

| 4 | 128.4 | 128.4 | 127.9 | 128.0 | 121.1 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 28.8 | 3.07 (15.7, 8,4) | dd | 28.9 | 3.03 (15.8, 8.7) | dd | 28.8 | 3.02 (16.1, 8.7) | dd | 28.8 | 3.05 (15.6, 9.3) | dd | 29.1 | 2.47 (16.5, 12.3) | dd |

| 3.22 (15.7, 9.6) | dd | 3.18 (15.8, 9.2) | dd | 3.19 (15.7, 9.5) | dd | 3.20 (15.5, 8.2) | dd | 2.62 (16.7, 5.3) | dd | ||||||

| 6 | 86.1 | 5.13 (8.8) | t | 86.1 | 5.13 (9.0) | t | 85.6 | 5.11 (9.1) | t | 86.0 | 5.10 (9.0) | t | 33.0 | 2.11 | m |

| 7 | 71.0 | 71.2 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 83.1 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 54.2 | 1.25 | m | 54.1 | 1.20 | m | 54.1 | 1.16 | m | 54.0 | 1.25 | m | 41.9 | ||

| 1.50 (13.6) | d | 1.48 (11.0) | d | 1.48 (13.6) | d | 1.49 | m | ||||||||

| 9 | 34.0 | 34.1 | 34.0 | 34.1 | 33.0 | 1.72 | m | ||||||||

| 1.83 | m | ||||||||||||||

| 10 | 42.7 | 1.28 | m | 42.7 | 1.17 | m | 42.7 | 1.15 | m | 42.4 | 1.33 | m | 30.6 | 2.22 (13.3, 3.7) | dd |

| 1.36 (14.5) | d | 1.36 (13.2) | d | 2.32 (12.7, 12.7, 12.7, 3.3) | dddd | ||||||||||

| 11 | 30.4 | 2.00 | m | 30.3 | 2.01 | m | 30.1 | 2.00 | m | 30.3 | 2.00 | m | 64.0 | 4.29 (12.6, 4.2) | dd |

| 2.24 (12.6, 12.6, 12.6, 2.8) | dddd | 2.22 (12.1, 12.1, 12.1, 2.7) | dddd | 2.22 (12.7, 12.7, 12.7, 2.4) | dddd | 2.23 (12.9, 12.9, 12.9, 2.7) | dddd | ||||||||

| 12 | 65.2 | 4.49 (12.2, 4.1) | dd | 65.5 | 4.29 (12.5, 4.1) | dd | 65.5 | 4.33 (12.5, 4.4) | dd | 64.8 | 4.51 (12.3, 4.4) | dd | 41.8 | ||

| 13 | 41.1 | 41.9 | 42.3 | 40.9 | 39.6 | 1.41 (14.2, 4.7) | m | ||||||||

| 1.57 (14.2, 4.7) | dd | ||||||||||||||

| 14 | 39.5 | 1.37 | m | 41.2 | 2.07 | m | 41.2 | 2.11 | m | 34.0 | 1.60 | m | 21.3 | 1.80 | m |

| 1.95 | m | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | 20.7 | 1.75 | m | 119.3 | 5.47 (15.4, 7.3, 7.3) | ddd | 123.3 | 5.50 (15.7, 7.7, 7.7) | ddd | 30.4 | 2.41 | m | 123.9 | 5.12 (6.8) | t |

| 1.93 | m | 2.81 | m | ||||||||||||

| 16 | 124.1 | 5.08 (15.4, 7.2) | dd | 143.1 | 5.64 (15.4) | d | 138.5 | 5.65 (15.7) | d | 202.0 | 131.8 | ||||

| 17 | 130.8 | 69.1 | 80.0 | 143.4 | 25.8 | 1.71 | s | ||||||||

| 18 | 25.5 | 1.66 | s | 30.1 | 1.19 | s | 24.4 | 1.26 | s | 125.6 | 5.90 | s | 129.9 | 7.83 | m |

| 6.17 | s | ||||||||||||||

| 19 | 130.2 | 7.68 (8.0) | d | 130.2 | 7.68 (8.7) | d | 129.9 | 7.67 (8.2) | d | 129.9 | 7.66 (8.3) | d | 117.3 | 6.79 (8.4) | d |

| 20 | 108.3 | 6.75 (8.1) | d | 108.3 | 6.73 (8.4) | d | 107.7 | 6.70 (8.4) | d | 108.1 | 6.71 (8.4) | d | 159.0 | ||

| 21 | 163.6 | 163.5 | 162.9 | 163.1 | 29.4 | 1.18 | m | ||||||||

| 1.85 | m | ||||||||||||||

| 22 | 36.3 | 1.32 | m | 36.3 | 1.27 | m | 36.2 | 1.25 | m | 36.1 | 1.32 | m | 22.4 | 1.63 | m |

| 2.34 | m | 2.31 | m | 2.31 | m | 2.30 | m | ||||||||

| 23 | 20.0 | 1.48 | m | 19.8 | 1.41 | m | 19.7 | 1.42 | m | 19.8 | 1.43 | m | 42.5 | 1.69 | m |

| 1.51 | m | ||||||||||||||

| 1.59 | m | 1.60 | m | ||||||||||||

| 24 | 47.5 | 1.31 | m | 48.0 | 1.18 | m | 48.1 | 1.15 | m | 47.2 | 13.3 | 1.19 | s | ||

| 25 | 21.1 | 0.96 | s | 20.9 | 0.96 | s | 20.8 | 0.96 | s | 21.0 | 0.96 | s | 15.0 | 1.15 | s |

| 26 | 19.1 | 0.83 | s | 18.7 | 0.85 | s | 18.5 | 0.86 | s | 19.0 | 0.87 | s | 19.5 | 1.01 | s |

| 27 | 17.4 | 1.60 | s | 30.4 | 1.17 | s | 25.0 | 1.23 | s | 17.3 | 1.78 | s | 17.7 | 1.65 | s |

Elucidation of the decalin ring system and isoprenoid head for 1 was performed by comparison with the NMR spectral data of callophycoic acid G 6 (SI).3 Key HMBC correlations from Me25 (δ 0.96) to C8 (δ 54.2), C10 (δ 42.7), and C24 (δ 47.5); from Me26 (δ 0.83) to C12 (δ 65.2) and C24; from both H11 (δ 2.00 and δ 2.24) to C10 and C12; and from H22b (δ 2.34) to C7, C8, and C24 established the connectivity of the decalin. The major difference between 6 and 1 is in the attachment of the benzoic acid moiety to the decalin. In 1, this attachment is made at C7, as indicated by HMBC and COSY correlations (SI), whereas in 6, this position is occupied by a double bond, indicating different cyclization pathways to yield functionalized decalin ring systems. Consistent with an alcohol functional group, a broad absorption in the IR spectrum at 3308 cm−1 was noted for 1. The final hydroxyl group of the molecular formula was placed on C7 due to its downfield chemical shift.

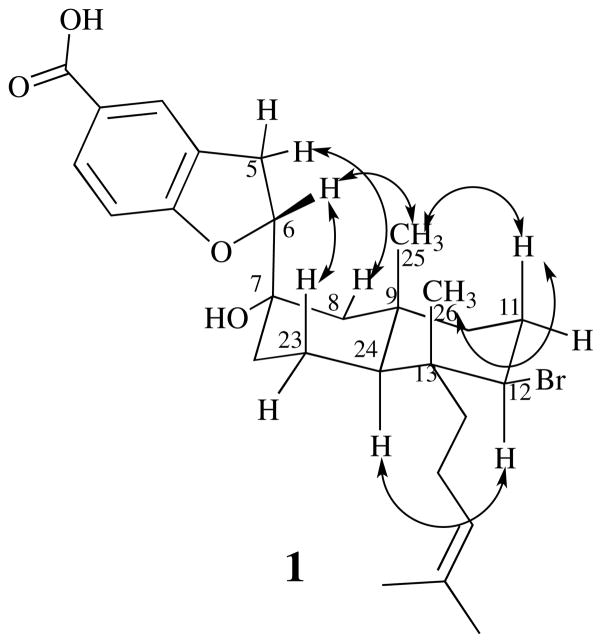

Relative stereochemistry of the decalin system of 1 was determined based on observed 1H NOE NMR data (SI and Figure 2) and by comparison with 6.3 NOEs between Me26 and H11b, and between H11b and Me25 placed these protons on the same face of the molecule. An NOE between H12 (δ 4.49) and H24 (δ 1.31), but not to Me25, Me26, or H11b, placed these protons on the opposite face of the molecule. The series of NOEs along the top face of the molecule established C7 as being in the S* configuration (relative to positions in the decalin system), including a crucial NOE between H6 and Me25 and a strong NOE between the axial proton at position 23 and H6. Given the stereochemistry of C7, now fixed relative to the decalin system, the NOE signal between H5b and equatorial proton H8b (δ 1.50) could only be accounted for by C6 being in the R* configuration (relative to positions in the decalin system and C7). Absolute stereochemistry was left unassigned.

Figure 2.

NOEs observed for bromophycoic acid A (1) (see Supporting information).

HRESI-MS of 2 gave an [M-H]− m/z of 519.1748, supporting a molecular formula of C27H37BrO5 with nine degrees of unsaturation and exhibiting an isotopic splitting pattern identical to 1. Examination of the 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR spectral data for 2 indicated that the substituted benzoic acid, 2,3-dihydrofuran, and decalin ring system of 1 were intact, but with one additional hydroxylated carbon at δ 69.1. Both Me18 (δ 1.19) and Me27 (δ 1.17) of 2 showed HMBC correlations to hydroxylated quaternary C17 (δ 69.1) and olefinic C16 (δ 143.1). Whereas 1H NMR and HSQC data indicated a C15 methylene in 1, the data were consistent with an olefinic carbon at this position in 2 (δ 119.3). A large (15.4 Hz) coupling between H15 (δ 5.47) and H16 (δ 5.64) in 2 led us to assign the E configuration.

For 3, mass spectrometric analysis gave HRESI-MS [M-H]− m/z of 535.1697 indicating a molecular formula of C27H37BrO6 and retaining the same nine degrees of unsaturation of 1 and 2. As with 1, the IR spectrum of 3 showed a broad absorption at 3388 cm−1 consistent with a least one hydroxyl moiety, and a C=O stretch at 1685 cm−1 associated with a carboxylic acid functional group. 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts for 3 were nearly identical to 2. HMBC correlations from Me18 (δ 1.26) and Me27 (δ 1.23) to quaternary C17 (δ 80.0) and olefinic C16 (δ 138.5), of H16 (δ 5.65) to C15 (δ 123.3), and COSY correlations between H14 (δ 2.11) and H15 (δ 5.50) established the isoprenoid head of 3 and revealed that 3 differed significantly from 2 only at position C17 (δ 69.1 in 2 vs. δ 80.0 in 3). As the molecular formula of 3 possessed only one additional oxygen relative to 2, a placement of hydroperoxide on C17 was supported by an IR absorption at 1170 cm−1.9–11 A large coupling (15.7 Hz) between H15 and H16 led us to the same E configuration as for 2. Evidence of this compound by mass spectrometry within minimally handled algal crude extracts suggested that it was not likely to be an artifact of isolation.

Mass spectral analysis of bromophycoic acid D (4) showed an isotopic splitting pattern identical to 1 and an [M-H]− m/z by HRESI-MS of 517.1590, which corresponds to a molecular formula of C27H35BrO5 and one more degree of unsaturation than 1. As with 1, 4 possessed a trisubstituted benzoic acid, 2,3-dihydrofuran, and decalin ring system as indicated by 2D NMR HMBC and COSY correlations (SI). Analysis of 1H NMR and HMBC spectral data showed one fewer methyl group at the isoprenoid head of 4 relative to 1. Me27 (δ 1.78) displayed HMBC correlations to olefinic C17 (δ 143.4) and C18 (δ 125.6) and to carbonyl C16 (δ 202.0), which established the isoprenoid head. Two vinyl protons (δ 5.90 and 6.17) attached to C18, with HMBC correlations to C16 and C17, confirmed the α, β-unsaturated ketone moiety. NOE correlations were consistent for 1–4, supporting the same relative stereochemistries for all (SI).

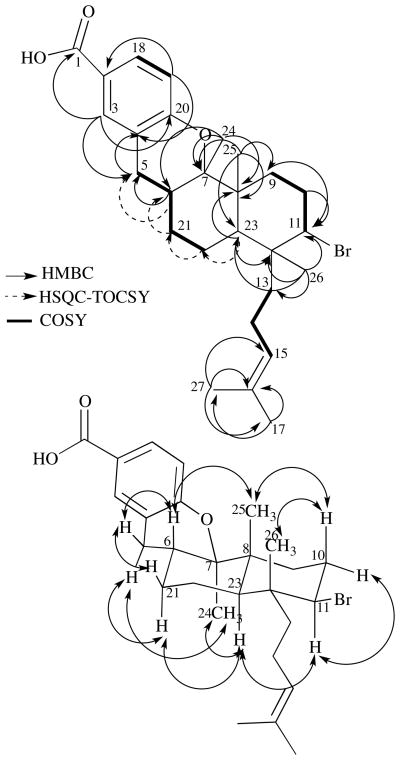

Bromophycoic acid E (5) gave an HRESI-MS signal at m/z 487.1845 with the same isotopic splitting pattern as 1. This mass analysis suggested a chemical formula of C27H37O3Br with nine degrees of unsaturation. Analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data indicated the same tri-substituted benzoic acid group as in 1–4 and 6. Key HMBC correlations from Me26 (δ 1.01) to C23 (δ 42.5) and from Me25 (δ 1.15) to C7 (δ 83.1), C9 (δ 33.0), and C23 established the connection within the decalin ring system as in 1 (Figure 3). Whereas 4 possessed one less methyl group than 1, 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of 5 revealed the presence of an additional methyl group (relative to 1), Me24 (δ 1.19), which was placed on the west cyclohexane of the decalin system based on HMBC correlations from Me24 to C6 (δ 33.0), C7, and C8 (δ 41.9). HMBC correlations from both H5 (δ 2.47, 2.62) to C4 (δ 121.1) on the aryl system and a COSY correlation from both H5 to H6 (δ 2.11) attached the benzoic acid to the decalin moiety. COSY correlations were observed between H6 and both H21 (δ 1.18, δ 1.85), and between H21a and H22 (δ 1.63). HSQC-TOCSY correlations from H23 (δ 1.69) to C22 (δ 22.4), from H22 to C21 (δ 29.4), from both H21b to C6, and from H6 to C5 (δ 29.1) established the connectivity as 5-6-21-22-23 (SI). On the basis of the molecular formula, one remaining degree of unsaturation, and 13C NMR chemical shift predictions, we assigned the fourth ring of the molecule as a six-membered cyclic ether, connecting C20 of the aryl system with C7 of the decalin.

Figure 3.

Top: Key COSY (bolded lines), HMBC (solid, single-head arrows), and HSQC-TOCSY (dashed, single-head arrows) correlations supporting the structure of bromophycoic acid E (5). Bottom: NOEs observed for bromophycoic acid E (5) represented by double-headed arrows. NOE between Me25 (δ 1.15) and Me26 (δ 1.01) could not be confirmed due to near-overlapping chemical shifts.

Relative stereochemistry of 5 was assigned based on observed NOEs (Figure 3 and SI). NOE correlations between H6 and Me25, Me25 and H10b (δ 2.32), and between H10b and Me26 indicated that these protons exist on the same face of the decalin. NOE correlations between Me24 and H23, between H11 (δ 4.29) and H10a, H11 and H21a, and H11 and H23, but not with any of the aforementioned protons, indicated that these protons lie on the opposite face of the molecule. Absolute stereochemistry was left unassigned.

The biosynthesis of bromophycoic acids A-D (1–4) is expected to progress through traditional meroditerpene biosynthesis where coupling of the benzoic acid moiety to geranylgeranyl diphosphate occurs by electrophilic aromatic substitution.12 This is likely followed by epoxidation or halogenation of the Δ6,7 olefin, via a bromonium ion equivalent, to a 2,3-dihyrofuran constructed by a 5-exo tetrahedral addition reaction with the phenolic hydroxyl, followed by elimination to yield a Δ7,8 olefin. The remaining linear diterpene would be expected to undergo a series of addition and elimination reactions resulting in the halogenation, cyclization, and hydroxylation as previously reported in terpene biosynthesis.13

Bromophycoic acid E (5) exhibits an unusual connection of the aryl group to a head carbon of the last isoprene unit. Thus, biosynthesis of 5 likely occurs through an electrophilic aromatic substitution with a 1,3-diene to form the connection of the benzoic acid to the diterpene. This could be followed by formation of the decalin ring system through the same series of addition and elimination reactions as 1–4. The final step would be the closure of the ether ring, possibly accomplished by a hydride shift followed by the capture of the phenolic hydroxyl group.

Bromophycoic acids A-E (1–5) add two novel carbon skeletons and five new natural products to a growing class of meroditerpenes isolated from red macroalgae,1–5,14,15 enhancing the already detailed structure-activity relationships of these related compounds. Bromophycoic acid A (1) displayed similar activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to its closest relative, callophycoic acid G (6) (Table 2),3 which lacks the dihydrofuran moiety. Notably, both 1 and 6 showed comparable activity to current MRSA treatments, such as vancomycin (MIC = 2 μg/mL) and linezolid (MIC = 2 μg/mL).16 Bromophycoic acids B-D (2–4), in which the isoprenoid head is oxygenated, demonstrated decreased antibiotic potency against MRSA. Bromophycoic acid E (5), with a fused cyclic ether, was the most potent bromophycoic acid against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecilis (VREF), but exhibited weaker activity than structurally related callophycoic acid A (7) (Table 2).3 Bromophycoic acid C (3), with modest activity against MRSA, was most active among bromophycoic acids and callophycoic acids against the malaria parasite P. falciparum with an IC50 of 8.7 μM. Compared with macrocyclic bromphycolide A (IC50 = 0.5 μM),17 however, this activity is modest. Nevertheless, it is the first among non-macrocyclic benzoic acid-diterpene metabolites to show appreciable activity against a protozoan parasite. Bromophycoic acid D (4) was the only bromophycoic or callophycoic acid to exhibit an average cytotoxity in the low micromolar range (average IC50 = 6.8 μM) against a panel of 14 human tumor cell lines (Table 2 and SI), being most active against the cell line PA-1 (human ovarian teratocarcinoma), with an IC50 of 2.0 μM. No significant antitubercular or antifunal activity was detected for these novel natural products (SI).

Table 2.

Pharmacological activities of bromophycoic acids A-E (1–5), compared with previously published callophycoic acids G (6) and A (7).4

| Antibacterial MICb (μg/mL)

|

Antimalarial IC50 (μM) | Cancer Cell Line Cytotoxicity IC50 (μM)a | Cell Line Selectivity max IC50/min IC50 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA | VREF | ||||

| bromophycoic acid A (1) | 1.6 | 6.3 | 30.7 | 36.0 | >4.7 |

| bromophycoic acid B (2) | 25.0 | <50 | 41.3 | 24.0 | >1.5 |

| bromophycoic acid C (3) | 6.3 | <50 | 8.7 | 15.3 | >4.0 |

| bromophycoic acid D (4) | 12.5 | <50 | 27.0 | 6.8 | 10.6 |

| bromophycoic acid E (5) | 6.3 | 1.6 | >100 | 13.7 | >5.0 |

| callophycoic acid G (6) | 1.6 | 3.1 | >100 | >25 | |

| callophycoic acid A (7) | <50 | 0.8 | 41.0 | 25.0 | |

Mean of 14 cancer cell lines (see experimental section and SI for details);

MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VREF = vanomycin-resistant Enterococcus facium

NT indicates not tested

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Biological Material

ICBG sample G-0807 was collected on 06 April 2010 between 10–20 m on channel walls and the reef slope near the Mango Bay Resort, Viti Levu, Fiji (18° 14′ 12″ S, 177° 46′ 48″ E). A voucher specimen is deposited at the University of South Pacific.

Genomic DNA from replicate ethanol-preserved G-0807 samples was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue Extraction Kit. The nuclear small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene was amplified via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in three separate reactions using primers (G01/G09, G02/G08, and G04/G07: Saunders and Kraft 1994). The cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene was amplified via PCR using primers designed from conserved regions of red algal COI from GenBank (COIfor: 5′-TTTAGGTGGCTGCATGTCAA-3′, COIrev: 5′-TTAAAAGCATTGTAATAGCACCTG-3′). PCR amplifications were performed in 10 μl volume solutions with 10–50 ng genomic DNA, 0.2 U Taq DNA polymerase and a final concentration of 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.001% gelatin, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 μM of gene-specific forward and reverse primers. Thermal cycling conditions consisted of 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 50 °C for 90 sec, 72 °C for 90 sec. PCR amplicons, visualized on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide, were gel extracted using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit. All DNA fragments were sequenced in both directions and sequences were manually edited in BioEdit vers 7.0.5.318 and aligned using ClustalW.19 Sequence similarity to other red algal taxa was determined in a BLAST search20 of sequences deposited in the GenBank nucleotide database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

Phylogenetic positioning of G-0807 within the subclass Rhodymeniophycidae (division Rhodophyta; class Florideophyceae) was determined through phylogenetic analysis using representatives of five orders with the Rhodymeniophycidae (Ceramiales, Gelidiales, Gigartinales, Gracilariales and Rhodymeniales) and outgroup taxa from subclasses Hildenbrandiophycide (order Hildebrandiales) and Corallinopycidae (order Corallinales). 18S rRNA and COI sequences from representative species were obtained from GenBank (SI). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in PhyML 3.0 aLRT21 using maximum likelihood criteria. Bootstrapping confidence values were determined over 1000 iterations.

Pharmacological Assays

Fractionation was guided by growth inhibition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, ATCC 33591) as previously described.1 Positive control for MRSA assay was vancomycin (MIC ≤ 2 μg/mL) and negative control was DMSO. Isolated compounds were additionally screened for antibacterial activity against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faceium (VREF; positive control was chloramphenicol (MIC ≤ 1 μg/mL) and negative control DMSO), antifungal activity against amphotericin-resistant Candida albicans (positive control was a 1:1 mixture of amphotericin B/cycloheximide (MIC ≤ 5 μg/mL) and negative control was DMSO),1 antitubercular activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv (ATCC 27294),22 antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (3D7 strain MR4/ATCC) as described previously (positive controls were chloroquine (IC50 = 5.8 nM) and artemisinin (IC50 = 6.2 nM) and negative control was DMSO),3 and against a panel of tumor cell lines including breast, colon, lung, prostate, and ovarian cancer cells as previously described.23 Specific cancer cells lines were the following: AU565, H3396, HCC1143, HCC70, HCT116, KPL4, LNCaP-FGC, LS174T, MCF-7, MDA-MB-468, SW403, T47D, ZR-75-1, PA-1.

Isolation of bromophycoic acids 1-5

Frozen algae of collection G-0807 (200 mL by volumetric displacement; 39.4 g dry mass) was exhaustively extracted with methanol and methanol/dichloromethane (1:1). Filtered extracts were combined and concentrated in vacuo. This crude extract was adsorbed onto Diaion HP20ss for vacuum liquid chromatography. After a 100% water wash, sequential elution with 1:1 MeOH/H2O, 4:1 MeOH/H2O, 100% MeOH, and 100% acetone (200 ml each) created four fractions (1–4). Fractions 2 (142.2 mg) and 3 (463.0 mg) were separated and purified by reversed-phase HPLC using either a Grace C18-silica 5 μM column measuring either 10 × 250 mm for semi-preparative scale separations or 4.6 × 250 mm for analytical scale purifications and a gradient from 85% aqueous MeOH with 0.1% formic acid to 100% MeOH with 0.1% formic acid over 25 min. Pure compounds were quantified by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 2,5-dimethyl furan as internal standard in 99.9% MeOD as previously described.24 High-resolution mass spectra were measured using an Orbitrap mass analyzer in negative mode.

Bromophycoic acid A (1): white amorphous solid (12.2 mg); 0.031 % plant dry mass); [α]27D +29 (c 0.23 g/100 mL, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 265 (2.54) nm; IR (thin film) υmax 3535 (br), 3308 (br), 2928, 1683, 1611, 1450, 1387, 1248, 1189, 1120, 1044, 992, 931, 871, 833, 757, 659 cm−1; for 1H and 13C NMR see Table 1; for COSY, HMBC, and NOE data see the Supporting Information; HRESI-MS m/z 503.1797 [M-H]− (calcd for C27H36O4 79Br 503.1791).

Bromophycoic acid B (2): white amorphous solid (1.8 mg); 0.004 % plant dry mass); [α]27D −11 (c 0.097 g/100 mL, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 265 (3.41) nm; IR (thin film) υmax 3566, 3390 (br), 3053, 2932, 1699, 1611, 1492, 1446, 1388, 1265, 1243, 1229, 1174, 1114, 1025, 993, 935, 834, 774, 737, 702, 651, 507; for 1H and 13C NMR see Table 1; for COSY, HMBC, and NOE data see the Supporting Information; HRESI-MS m/z 519.1748 [M-H]− (calcd for C27H36O5 79Br 519.1741).

Bromophycoic acid C (3): white amorphous solid (2.9 mg); 0.007 % plant dry mass); [α]27D +1.6 (c 0.118 g/100 mL, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 265 (3.35) nm; IR (thin film) υmax 3388 (br), 2938, 1685, 1609, 1448, 1386, 1248, 1170, 1114, 1034, 975, 935, 868, 832, 757, 668 cm−1; for 1H and 13C NMR see Table 1; for COSY, HMBC, and NOE data see the Supporting Information; HRESI-MS m/z 535.1697 [M-H]− (calcd for C27H36O6 79Br 535.1690).

Bromophycoic acid D (4): white amorphous solid (0.7 mg); 0.002 % plant dry mass); [α]27D −67 (c 0.030 g/100 mL, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 265 (3.85) nm; for 1H and 13C NMR see Table 1; for COSY, HMBC, and NOE data see the Supporting Information; HRESI-MS m/z 517.1590 [M-H]− (calcd for C27H35O5 79Br 517.1584).

Bromophycoic acid E (5): white amorphous solid (1.4 mg); 0.004 % plant dry mass); [α]27D +34 (c 0.027 g/100 mL, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 264 (3.93) nm; for 1H and 13C NMR see Table 1; for COSY, HMBC, and NOE data see the Supporting Information; HRESI-MS m/z 487.1845 [M-H]− (calcd for C27H36O3 79Br 487.1842).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by ICBG grant U01-TW007401 from the Fogarty International Center of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the Government of Fiji and the customary fishing right owners for permission to perform research in their territorial waters. We thank J. Nahabadien and C. Lane for antimicrobial assays; G. Kraft for morphological assessment of algal specimens; G. Saunders for genetic assessment of algal specimens; A. N’Yeurt for additional assistance on the identification of algal specimens; D. Bostwick for mass spectroscopic analyses; L. Gelbaum for NMR assistance; S. G. Franzblau for assays using Mycobacterium tuberculosis; D. Rasher for collection of algal samples; and J.C. Morris for use of the FT-IR instrument.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional bioactivity data including antifungal and individual cancer cell lines; COSY, HMBC, and NOE data for 1–5; 1H, 13C, COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOE spectra for 1–5; Phylogenetic analysis of Callophycus sp G-0807. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Kubanek J, Prusak AC, Snell TW, Giese RA, Hardcastle KI, Fairchild CR, Aalbersberg W, Raventos-Suarez C, Hay ME. Org Lett. 2005;7:5261. doi: 10.1021/ol052121f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubanek J, Prusak AC, Snell TW, Giese RA, Fairchild CR, Aalbersberg W, Hay ME. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:731. doi: 10.1021/np050463o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane AL, Stout EP, Hay ME, Prusak AC, Hardcastle K, Fairchild CR, Franzblau SG, Le Roch K, Prudhomme J, Aalbersberg W, Kubanek J. J Org Chem. 2007;72:7343. doi: 10.1021/jo071210y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane AL, Stout EP, Lin AS, Prudhomme J, Le Roch K, Fairchild CR, Franzblau SG, Hay ME, Aalbersberg W, Kubanek J. J Org Chem. 2009;74:2736. doi: 10.1021/jo900008w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin AS, Stout EP, Prudhomme J, Le Roch K, Fairchild CR, Franzblau SG, Aalbersberg W, Hay ME, Kubanek J. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:275. doi: 10.1021/np900686w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraft GT. Phycologia. 1984;23:53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane AL, Nyadong L, Galhena AS, Shearer TL, Stout EP, Parry RM, Kwasnik M, Wang MD, Hay ME, Fernandez FM, Kubanek J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812020106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crews P, Rodríguez J, Jaspars M. Organic Structure Analysis. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegazy MEF, Eldeen AMG, Shahat AA, Abdel-Latif FF, Mohamed TA, Whittlesey BR, Pare PW. Mar Drugs. 2012;10:209. doi: 10.3390/md10010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griesbeck AG, Cho M. Tet Lett. 2009;50:121. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverstein RM, Webster FX, Kiemle DJ. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. 7. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleh O, Haagen Y, Seeger K, Heide L. Phytochem. 2009;70:1728. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler A, Carter-Franklin JN. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:180. doi: 10.1039/b302337k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stout EP, Hasemeyer AP, Lane AL, Davenport TM, Engel S, Hay ME, Fairchild CR, Prudhomme J, Le Roch K, Aalbersberg W, Kubanek J. Org Lett. 2009;11:225. doi: 10.1021/ol8024814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stout EP, Prudhomme J, Roch KL, Fairchild CR, Franzblau SG, Aalbersberg W, Hay ME, Kubanek J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:5662. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegde SS, Reyes N, Wiens T, Vanasse N, Skinner R, McCullough J, Kaniga K, Pace J, Thomas R, Shaw JP, Obedencio G, Judice JK. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3043. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3043-3050.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stout EP, Cervantes S, Prudhomme J, France S, La Clair JJ, Le Roch K, Kubanek J. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:1572. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall TA. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anisimova M, Gascuel O. Syst Biol. 2006;55:539. doi: 10.1080/10635150600755453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee FY, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, Kim SH, Long BH, Reventos-Suarez C, Vite GD, Rose WC, Kramer RA. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerritz SW, Sefler AM. J Comb Chem. 2000;2:39. doi: 10.1021/cc990041v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.