Abstract

The structure-activity relationships of 6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives as selective antagonists at human A3 adenosine receptors have been explored (Jiang et al. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 39, 4667-4675). In the present study, related pyridine derivatives have been synthesized and tested for affinity at adenosine receptors in radioligand binding assays. Ki values in the nanomolar range were observed for certain 3,5-diacyl-2,4-dialkyl-6-phenylpyridine derivatives in displacement of [125I]AB-MECA (N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine) at recombinant human A3 adenosine receptors. Selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors was determined vs radioligand binding at rat brain A1 and A2A receptors. Structure–activity relationships at various positions of the pyridine ring (the 3- and 5-acyl substituents and the 2- and 4-alkyl substituents) were probed. A 4-phenylethynyl group did not enhance A3 selectivity of pyridine derivatives, as it did for the 4-substituted dihydropyridines. At the 2-and 4-positions ethyl was favored over methyl. Also, unlike the dihydropyridines, a thioester group at the 3-position was favored over an ester for affinity at A3 adenosine receptors, and a 5-position benzyl ester decreased affinity. Small cycloalkyl groups at the 6-position of 4-phenylethynyl-1,4-dihydropyridines were favorable for high affinity at human A3 adenosine receptors, while in the pyridine series a 6-cyclopentyl group decreased affinity. 5-Ethyl 2,4-diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate, 38, was highly potent at human A3 receptors, with a Ki value of 20 nM. A 4-propyl derivative, 39b, was selective and highly potent at both human and rat A3 receptors, with Ki values of 18.9 and 113 nM, respectively. A 6-(3-chlorophenyl) derivative, 44, displayed a Ki value of 7.94 nM at human A3 receptors and selectivity of 5200-fold. Molecular modeling, based on the steric and electrostatic alignment (SEAL) method, defined common pharmacophore elements for pyridine and dihydropyridine structures, e.g., the two ester groups and the 6-phenyl group. Moreover, a relationship between affinity and hydrophobicity was found for the pyridines.

Introduction

Selective antagonists have been reported for adenosine A1, A2A, and A3 receptors,1 which are members of the G-protein-coupled superfamily characterized by seven transmembrane helical domains (TMs). Activation of the A3 receptor has been linked to several second messenger systems, such as stimulation of phospholipases C2 and D3 and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase.1 Antagonists for the A3 adenosine receptor are sought as potential antiinflammatory, antiasthmatic, or anti-ischemic agents.4–8 The pharmacology of the A3 receptor is unique within the class of adenosine receptors.4,9–10 Most strikingly, xanthines such as caffeine and theophylline, which have provided versatile leads for antagonists at the other adenosine receptor subtypes, are much less potent at the A3 receptor. The most promising leads have arisen from library screening, resulting in the identification of 1,4-dihydropyridines,11–13 tri-azoloquinazolines,14 flavonoids,15 a triazolonaphthyridine,16 and a thiazolopyrimidine16 as prototypical A3 receptor selective probes. Furthermore, there are major species differences in the affinity of antagonists, e.g., typically many antagonists have 1–3 orders of magnitude greater affinity at human vs rat A3 receptors.

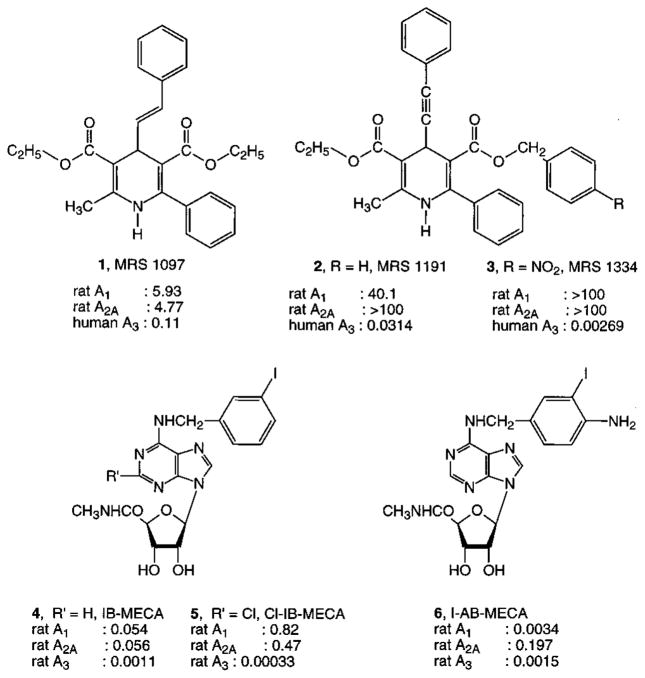

We previously reported that is was possible to separate the antagonism of L-type calcium channels from adenosine receptor antagonism among the 1,4-dihydropyridines, through the introduction of 6-aryl and either 4-phenylethynyl or 4-styryl substitution.11 These groups not only eliminated affinity for the L-type calcium channels but also greatly enhanced selectivity for the A3 receptor subtype. For example, a dihydropyridine derivative, 3,5-diethyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-[2-phenyl(E)-vinyl]-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (Figure 1, 1),11 has been found to inhibit binding of radioligand at the human A3 receptor with an affinity of 108 nM, while the same derivative was inactive at ion channels and other receptor sites. MRS 1191, 3-ethyl 5-benzyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (Figure 1, 2),12 competitively antagonized the effects of N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine (IB-MECA, Figure 1, 3), an A3 receptor selective agonist,17 on inhibition of adenylyl cyclase mediated by the recombinant human A3 receptor. Dihydropyridine antagonists of A3 receptors have also proven selective in chick cardiac myocytes, in which the activation of A3 receptors induces protective anti-ischemic effects.18 MRS 1191 was also shown to be A3 receptor-selective in the rat hippocampus,19 in which it was demonstrated that A3 receptor activation suppresses the effects of activation of presynaptic A1 receptors on inhibition of neurotransmitter release. MRS 1191 was also utilized to demonstrate that presynaptic A3 receptor activation antagonizes metabotropic glutamate autoreceptors.20 Most of the dihydropyridine adenosine A3 receptor antagonists have been designed through a classical medicinal chemical approach to rational drug design. An alternate approach that has been explored is called the “functionalized congener approach”,21,22 in which an easily derivatized functional group is incorporated at the end of a strategically designed and attached chain substituent.22

Figure 1.

Structures of key A3 adenosine receptor selective antagonists and agonists. Ki values in micromolar were reported in refs 16–20.

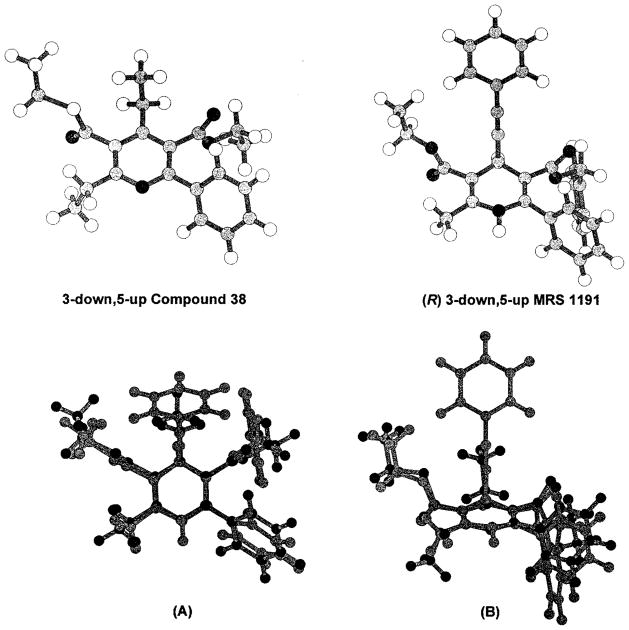

Figure 2.

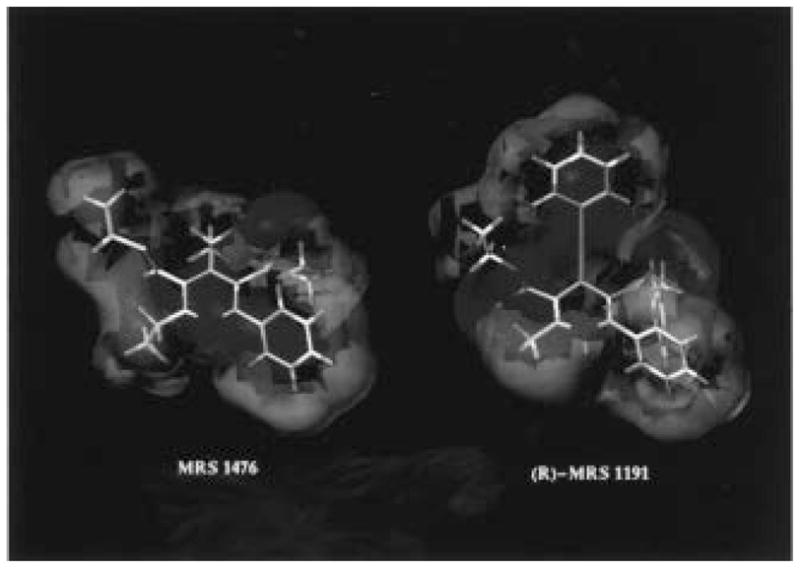

Top: Optimized geometries for the conformers 3-down,5-up of compound 38 and (R)-MRS 1191. Bottom: Alignments generated by SEAL for the conformers 3-down,5-up of compound 38 and (R)-MRS 1191, viewed from the top (A) and from the front (B).

Figure 3.

Comparison between the isopotential surfaces of (R)-MRS 1191 and compound 38 (red = 5 kcal/mol, and blue = −5 kcal/mol).

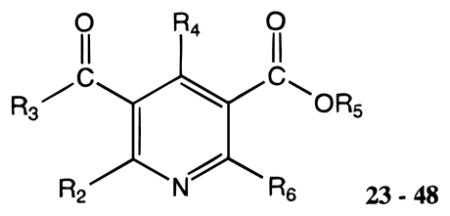

In the previous studies,11–13 a few pyridine derivatives were synthesized but no advantage for A3 receptor selectivity was evident. In the present study, we have used the 1,3-diacylpyridine nucleus, obtained through oxidation of the corresponding 1,4-dihydropyridine, as a template for probing structure–activity relationships (SAR) at adenosine receptors and have identified combinations of substituents resulting in high selectivity for human A3 receptors. Thus, it has been possible to compare the structural requirements for the two related classes of compounds and to propose a basis for the major differences in a molecular model of the ligand binding site of the human A3 receptor. Most notably, bulky substituents at the 4-position and a 5-benzyl ester, which are affinity-enhancing in dihydropyridines,12,13 are not well tolerated in the pyridine series for A3 receptor binding. At other positions, structural parallels occur between corresponding dihydropyridine and pyridine analogues.

Results

Synthesis

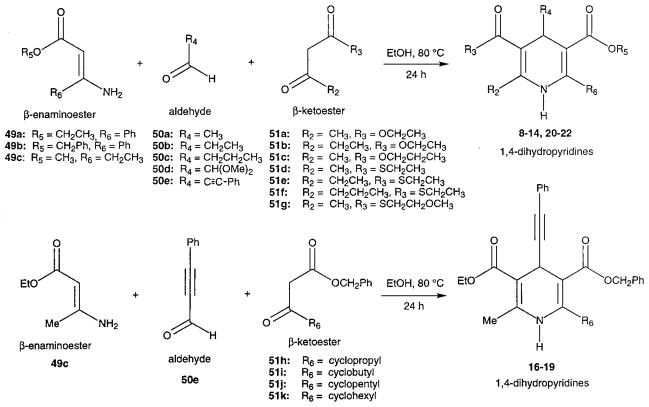

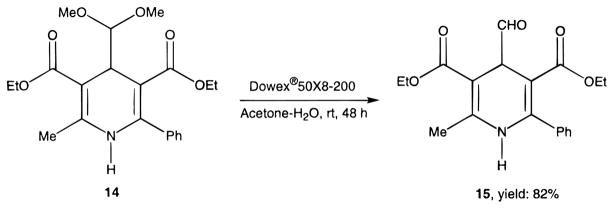

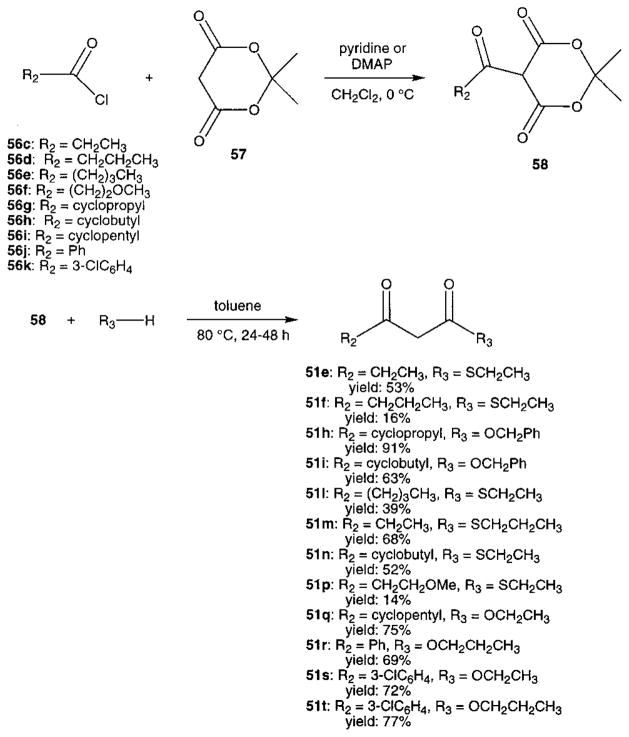

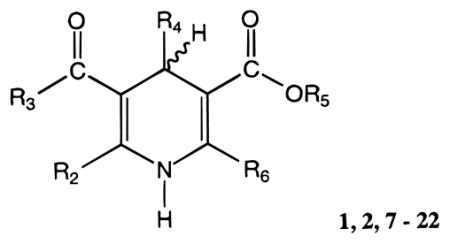

Novel 1,4-dihydropyridines (1, 2, and 7–22) and closely related pyridine derivatives (23–48) synthesized and tested for affinity in radioligand binding assays at adenosine receptors are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. As in the previous studies,17,18 the dihydropyridine (Schemes 1 and 2) and pyridine (Scheme 3) analogues were prepared as shown. The Hantzsch condensation, Scheme 1, which involved condensing three components, a 3-amino-2-propenoate ester (49, Scheme 4), an aldehyde (50, for example, Scheme 5), and a β-ketoester (51, Schemes 6 and 7), was used for the 1,4-dihydropyridines. The corresponding pyridines were prepared through oxidation of the dihydropyridines using tetrachloroquinone (Scheme 3). Synthesis of the 3-amino-3-phenyl-2-propenoate esters, 49, was performed by refluxing the corresponding benzoyl acetate ester and ammonium acetate in ethanol (Scheme 4). An aldehyde containing a dimethylacetal group, 50d, was prepared from the corresponding olefin, 53, through sequential oxidation with potassium permanganate and sodium periodate (Scheme 5).41 Ketoesters and ketothioesters were prepared as shown in Scheme 6.23 Alternately, a more versatile route through acylation of the cyclic compound 57, Meldrum’s acid,42 followed by opening of the ring with an alcohol or thiol40 and decarboxylation was also adopted for compounds 51 (Scheme 7). A formyl group was introduced at the 4-position of the dihydropyridines and pyridines via protected dimethyl acetal derivatives, 14 and 30 (Scheme 2). The acid deprotection using a sulfonate ion-exchange resin was carried out successfully on a dihydropyridine or pyridine derivative. Yields and characterization are shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Affinities of 1,4-Dihydropyridine Derivatives in Radioligand Binding Assays at A1, A2A, and A3 Receptors

1,2,7 – 22 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 |

Ki (μM) or % inhibitiond

|

|||

| rA1a | rA2Ab | hA3c | rA1/hA3 | ||||||

| 7e | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 25.9 ± 7.3 | 35.9 ± 15.3 | 7.24 ± 2.13 | 3.6 |

| 8 | CH3 | OCH2CH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 17.4 ± 3.1 | 28.9 ± 4.8 | 2.11 ± 0.35 | 8.2 |

| 9 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 21.9 ± 3.3 | 21.8 ± 7.8 | 2.27 ± 0.64 | 9.6 |

| 10 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 35.4 ± 4.5 | 54.8 ± 18.8 | 2.01 ± 0.55 | 18 |

| 11 | CH3 | SCH2CH2OCH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 36 ± 14% (10−4) | 12.5 ± 2.5 | 4.58 ± 0.35 | >10 |

| 12 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 48 ± 5% (10−4) | 29 ± 10% (10−4) | 2.17 ± 0.25 | >20 |

| 13 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2Ph | Ph | 45 ± 2% (10−4) | 14.3 ± 4.2 | 1.65 ± 0.40 | >50 |

| 14 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH(OCH3)2 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 32 ± 5% (10−4) | d (10−4) | 15.3 ± 3.9 | >5 |

| 15 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CHO | CH2CH3 | Ph | 26 ± 6% (10−4) | 32 ± 15% (10−4) | 15.6 ± 5.4 | >6 |

| 1e | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-CH=CH-(trans) | CH2CH3 | Ph | 5.93 ± 0.27 | 4.77 ± 0.29 | 0.108 ± 0.012 | 55 |

| 2e | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | Ph | 40.1 ± 7.5 | d (10−4) | 0.0314 ± 0.0028f | 1300 |

| 16 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclopropyl | 22 ± 1% (10−4) | d (10−4) | 0.0277 ± 0.0024 | >3000 |

| 17 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclobutyl | 36 ± 8% (10−4) | d (10−4) | 0.0225 ± 0.0030 | >3000 |

| 18 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclopentyl | 17.1 ± 4.3 | 7.16 ± 1.56 | 0.0505 ± 0.0210 | 340 |

| 19 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclohexyl | 22 ± 2% (10−4) | 20% (10−4) | 0.229 ± 0.014 | >400 |

| 20 | CH2 CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 20 ± 4% (10−4) | d (10−4) | 2.83 ± 0.20 | >30 |

| 21 | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 34 ± 7% (10−4) | 29.1 ± 9.9 | 0.907 ± 0.044 | >50 |

| 22 | CH2 CH2CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 26 ± 19% (10−4) | d (10−4) | 2.09 ± 0.04 | >20 |

Displacement of specific [3H]R - PIA binding in rat brain membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–5), or as a percentage of specific binding displaced at the indicated concentration (M).

Displacement of specific [3H]CGS 21680 binding in rat striatal membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–6), or as a percentage of specific binding displaced at the indicated concentration (M).

Displacement of specific [125I]AB-MECA binding at human A3 receptors expressed in HEK cells, in membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n =3–4).

Displacement of ≤ 10% of specific binding at the indicated concentration (M).

Table 2.

Affinities of Pyridine Derivatives in Radioligand Binding Assays at A1, A2A, and A3 Receptors

23 – 48 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | rA1a | rA2Ab | hA3c | rA1/hA3 |

| 23e | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 7.41 ± 1.29 | 28.4 ± 9.1 | 4.47 ± 0.46 | 1.7 |

| 24 | CH3 | OCH2CH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 5.05 ± 0.54 | 24.5 ± 8.5 | 0.215 ± 0.022 | 23 |

| 25 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 3.36 ± 0.60 | 3.69 ± 1.25 | 0.176 ± 0.038 | 19 |

| 26 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 14.8 ± 3.5 | 14.9 ± 4.1 | 0.0429 ± 0.0088 | 340 |

| 27 | CH3 | SCH2CH2OCH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 36 ± 11% (10−4) | 7.98 ± 1.36 | 0.165 ± 0.012 | >500 |

| 28 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 29 ± 6% (10−4) | 7.53 ± 2.70 | 0.194 ± 0.051 | >700 |

| 29 | CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2Ph | Ph | 20 ± 8% (10−4) | 12.8 ± 2.9 | 2.61 ± 0.96 | >40 |

| 30 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH(OCH3)2 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 1.95 ± 0.43 | 2.88 ± 0.61 | 0.783 ±0.154 | 2.5 |

| 31 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CHO | CH2CH3 | Ph | 9.56 ± 4.09 | 2.56 ± 0.13 | 1.98 ± 0.21 | 4.8 |

| 32 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-CH=CH-(trans) | CH2CH3 | Ph | 2.49 ± 0.47 | 2.40 ± 0.22 | 2.80 ± 1.78 | 0.85 |

| 33 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | Ph | 11.6 ± 4.8 | 43±2% (10−4) | 2.75 ± 0.78 | 4.2 |

| 34 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclobutyl | d (10−4) | 27.6 ± 12.0 | 2.41 ± 0.59 | >40 |

| 35 | CH3 | OCH2CH3 | Ph-C≡C- | CH2Ph | cyclopentyl | 56.2 ± 20.8 | 22.9 ± 5.0 | 3.85 ± 0.79 | 15 |

| 36 | CH2 CH3 | OCH2CH3 | CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 10.3 ± 1.7 | 13.4 ± 4.2 | 0.121 ± 0.008 | 85 |

| 37 | CH2 CH3 | OH | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 4.25 ± 0.65 | 7.09 ± 0.97 | 1.28 ± 0.55 | 3.3 |

| 38 (MRS1476) | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 41 ± 6% (10−4) | 6.13 ± 1.28 | 0.0200 ± 0.0019 | >3000 |

| 39a | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | Ph | 7.77 ± 1.83 | d (10−5) | 0.00829 ± 0.00115 | 940 |

| 39b (MRS1523) | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | Ph | 15.6 ± 6.9 | 2.05 ± 0.44 | 0.0189 ± 0.0041 | 830 |

| 40 | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH2OH | Ph | 17.4 ± 5.29 | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 0.188 ± 0.061 | 93 |

| 41 | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | 3-Cl–Ph | 8.20 ± 2.96 | 8.91 ± 0.97 | 0.0134 ± 0.0015 | 610 |

| 42 | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | cyclopentyl | 55.3 ± 14.7 | 26.1 ± 6.2 | 3.38 ± 1.87 | 16 |

| 43 | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 8.22 ± 1.21 | 15.7 ± 4.4 | 0.0159 ± 0.0054 | 520 |

| 44 (MRS1505) | CH2 CH3 | SCH2CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH2CH3 | 3-Cl–Ph | 41.4 ± 11.9 | 24.1 ± 7.9 | 0.00794 ± 0.00319 | 5200 |

| 45 (MRS1486) | CH2 CH2CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 16.7 ± 3.0 | 2.82 ± 0.82 | 0.0333 ± 0.0107 | 500 |

| 46 | (CH2)2OCH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 10.1 ± 2.1 | 12.6 ± 1.7 | 0.0168 ± 0.0020 | 600 |

| 47 | (CH2)3CH3 | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 40.3 ± 7.4 | d (10−4) | 0.0350 ± 0.0091 | 1200 |

| 48 | cyclobutyl | SCH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 | Ph | 30 ± 1% (10–4) | 22% (10−4) | 0.145 ± 0.044 | >500 |

Displacement of specific [3H]R-PIA binding in rat brain membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–5), or as a percentage of specific binding displaced at the indicated concentration (M).

Displacement of specific [3H]CGS 21680 binding in rat striatal membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–6), or as a percentage of specific binding displaced at the indicated concentration (M).

Displacement of specific [125I]AB-MECA binding at human A3 receptors expressed in HEK cells, in membranes, expressed as Ki ± SEM in μM (n = 3–4).

Displacement of ≤ 10% of specific binding at the indicated concentration (M).

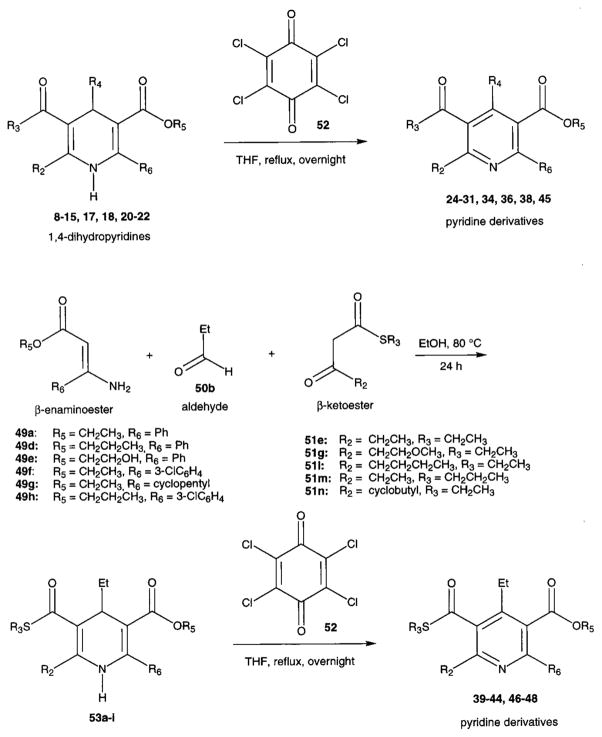

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Substituted 1,4-Dihydropyridines Using the Hantzsch Reaction

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of a 1,4-Dihydropyridine Containing an Aldehyde Group at the 4-Position

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Pyridine Derivatives

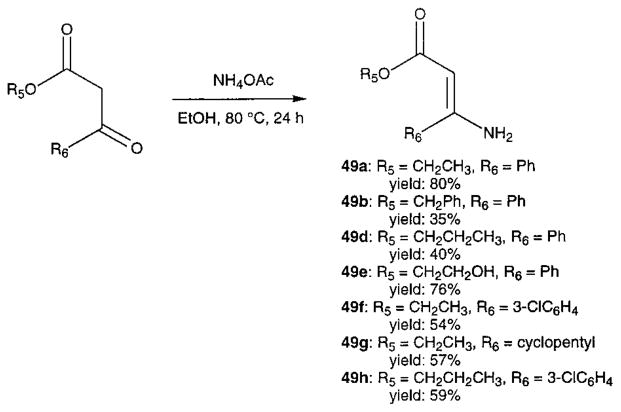

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of β-Amino-α,β-unsaturated Esters

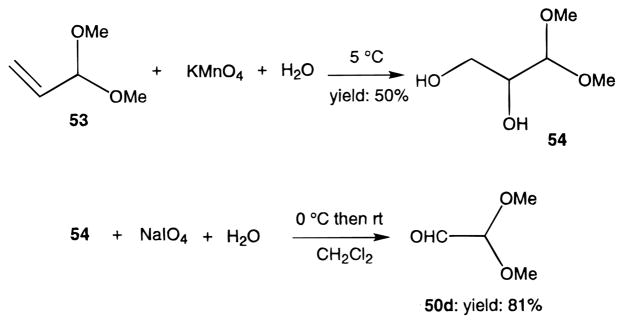

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of a Protected Aldehyde for Incorporation at the 4-Position of 1,4-Dihydropyridines

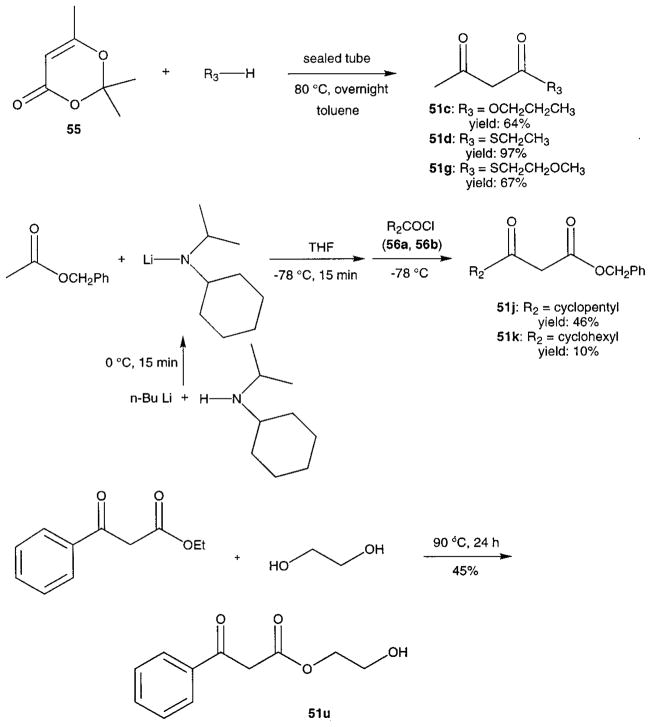

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of β-Ketoesters via Acylacetyl Esters

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of β-Ketoesters via Meldrum’s Acid

Table 3.

Yields and Analysis of Dihydropyridine and Pyridine Derivatives

| no. | formula | analysis | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | C20H25NO4·0.25H2O | C,H,N | 63 |

| 9 | C20H25NO4 | C,H,N | 55 |

| 10 | C20H25NO3S | C,H,N | 81 |

| 11 | C21H27NO4S | C,H,N | 68 |

| 12 | C21H27NO3S·0.1H2O | C,H,N | 54 |

| 13 | C25H27NO3S | C,H,N | 47 |

| 14 | C21H27NO6 | H,N,Ca | 30 |

| 15 | C19H21NO5 | HRMSc | 82 |

| 16 | C28H27NO4·0.5C3H6O | C,H,N | 24 |

| 17 | C29H29NO4·0.2H2O | C,H,N | 35 |

| 18 | C30H31NO4 | C,H,N | 16 |

| 19 | C31H33NO4 | C,H,N | 52 |

| 20 | C20H25NO4 | C,H,N | 58 |

| 21 | C21H27NO3S | C,H,N | 72 |

| 22 | C22H29NO3S | C,H,N | 45 |

| 24 | C20H23NO4 | HRMSd | 78 |

| 25 | C20H23NO4 | HRMSe | 85 |

| 26 | C20H23NO3S | C,H,N | 61 |

| 27 | C21H25NO4S | C,H,N | 65 |

| 28 | C21H25NO3S | C,H,N | 78 |

| 29 | C25H25NO3S | C,H,N | 82 |

| 30 | C21H25NO6 | HRMSf | 59 |

| 31 | C19H19NO5·0.4C7H8 | C,H,N | 55 |

| 34 | C29H27NO4 | C,H,N | 83 |

| 35 | C30H29NO4 | C,H,N | 34 |

| 36 | C20H23NO4 | HRMSg | 96 |

| 37 | C18H19NO4·0.1C7H8 | C,H,N | 56 |

| 38 | C21H25NO3S | C,H,N | 39 |

| 39a | C22H27NO3S | H,N,Cb | 85 |

| 39b | C23H29NO3S | C,H,N | 71 |

| 40 | C21H25NO4S | C,H,N | 54 |

| 41 | C21H24ClNO3S | C,H,N | 58 |

| 42 | C20H29NO3S | HRMSh | 52 |

| 43 | C22H27NO3S·0.1H2O | C,H,N | 79 |

| 44 | C23H28ClNO3S | C,H,N | 65 |

| 45 | C22H27NO3S | C,H,N | 51 |

| 46 | C22H27NO4S | HRMSi | 65 |

| 47 | C23H29NO3S | HRMSj | 53 |

| 48 | C23H27NO3S·0.6H2O | C,H,N | 64 |

Elemental analysis for compound 14. C, calculated: 64.76; found: 66.58. H, calculated: 6.99; found: 6.25.

Elemental analysis for compound 39a. C, calculated: 68.54; found: 70.16. The following compounds were shown to be pure on analytic TLC (silica gel 60, 250 μm) EtOAc–petroleum ether = 10:90 (v/v), unless noted.

Compound 15, Rf = 0.87; EI calcd for C18H20NO4 (M+ – CHO) 314.1392, found 314.1432.

Compound 24, Rf = 0.44; EI calcd for C20H23NO4 (M+) 341.1627, found 341.1635.

Compound 25, Rf = 0.35; EI calcd for C20H23NO4 (M+) 341.1627, found 341.1615.

Compound 30, EtOAc–petroleum ether = 20:80 (v/v), Rf = 0.36; EI calcd for C21H25NO6 (M+) 387.1682, found 387.1674.

Compound 36, Rf = 0.46; EI calcd for C20H23NO4 (M+) 341.1627, found 341.1631.

Compound 42, Rf = 0.51; EI calcd for C20H29NO3S (M+) 363.1868, found 363.1858.

Compound 46, Rf = 0.27; EI calcd for C22H27NO4S (M+) 401.1661, found 401.1666.

Compound 47, Rf = 0.54; EI calcd for C23H29NO3S (M+) 399.1868, found 399.1867.

Pharmacology

A Potency and Selectivity of 1,4-Dihydropyridines at Human A3 Receptors

1,4-Dihydropyridine analogues bearing small alkyl groups (methyl, ethyl, or propyl) at the 4-position (7–13, 20–22) displayed affinity at the human A3 receptor of between 1 and 7 μM and, at best, moderate selectivity vs rat A1 and A2A receptors (Table 1). Among small 4-alkyl groups, there was not a clear pattern of effect on the adenosine receptor affinity.

The receptor affinities of a series of 2-methyl-1,4-dihydropyridines (1, 2, and 7–19) were compared. Ester groups at the 3- and 5-positions were varied. At the 3-position, a propyl, 8, vs ethyl ester, 7, had no effect on the affinity at A1 and A2A receptors, while the affinity at A3 receptors increased 3-fold. A 3-thioethyl ester, 10, had the same A3 receptor affinity as the oxygen analogue, 9, and affinity at A1 and A2A receptors was marginally decreased. A 3-(2-methoxyethylthio)ester, 11, had 4-fold increased A2A receptor affinity vs the ethylthio analogue, 10, and affinity at A1 and A3 receptors was slightly decreased. A 5-benzyl ester, in the dihydropyridine series in which the 4-position substituent is a styryl or phenylethynyl group, has been reported to enhance A3 receptor selectivity.12,13 Among 4-ethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine 3-thioesters, the potency-enhancing effect of a 5-benzyl ester was not evident (13 vs 10), thus the effects of 4- and 5-position substituents are highly interdependent.

In the 5-ethyl ester series, homologation of the 4-position substituent from ethyl to propyl (10 vs 12) had no effect on A3 receptor affinity. Either a dimethyl acetal, 14, or the corresponding aldehyde, 15, at the 4-position had decreased adenosine receptor affinity. As reported previously, the 4-styryl, 1, or 4-phenylethynyl substituent, 2, in the dihydropyridine series greatly enhanced A3 receptor selectivity.

The 6-phenyl substituent, previously found to be optimal for A3 receptor affinity when unsubstituted, could be replaced with cycloalkyl rings of varying size in a series of 4-phenylethynyl-5-benzyl esters (16–19). A cyclopentyl substituent, in 18, resulted in nearly the same degree of A3 receptor affinity as the 6-phenyl analogue, 2. A 6-cyclohexyl substituent, in 19, did not provide as high an affinity in A3 receptor binding, but smaller rings resulted in very high affinity and selectivity. The 6-cyclopropyl and 6-cyclobutyl analogues, 16 and 17, displayed Ki values at A3 receptors of 28 and 23 nM, respectively.

Effects of alkyl group modification at the 2-position were also probed. A 2-ethyl vs 2-methyl substituent afforded a slight increase in A3 receptor affinity (21 vs 10) while slightly diminishing affinity at A1 and A2A receptors. A 2-propyl analogue, 22, was only half as potent at A3 receptors as the corresponding 2-ethyl analogue, 21.

B. Potency and Selectivity of Pyridines at Human A3 Receptors

In the pyridine series (23–48, Table 2), unlike the dihydropyridines, the analogues having small alkyl substituents at the 4-position tended to reach greater potency at human A3 receptors than those analogues bearing the 4-phenylethynyl or 4-styryl group (32–35).

The adenosine receptor affinities of a series of 2-methylpyridines, including 3-alkyl esters (23–25 and 30–35) and 3-alkylthioesters (26–29), were examined. At the 3-position, a thioester, 26, had a 4-fold greater affinity at A3 receptors than the oxygen analogue, 25, and affinity at both A1 and A2A receptors was decreased approximately 4-fold. A 3-propyl, 24, vs 3-ethyl ester, 23, also resulted in a major increase in A3 receptor affinity (21-fold), with little effect on affinity at A1 and A2A receptors. A 2-methyl-3-(2-methoxyethylthio)ester, 27, was 4-fold less potent at A3 receptors than the corresponding ethylthio analogue, 26. Unlike compound 2, a dihydropyridine, a 5-benzyl ester in the pyridine 3-thioester series greatly reduced A3 receptor affinity and selectivity (29 vs 25). A 3-carboxylic acid, 37, was nonselective in binding.

Similar to the affinity-increasing effect of homologation of 3-esters, at the 4-position, an ethyl, 25, vs methyl group, 23, resulted in a 25-fold increase in A3 receptor affinity. However, further extension of the 4-alkyl group was not beneficial for affinity at human A3 receptors. A 3-ethylthio-4-propyl analogue, 28, was 5-fold less potent at A3 receptors than the corresponding 4-ethyl analogue, 26; thus ethyl appeared to be the optimal 4-substituent among small alkyl groups. Consistent with this observation, the presence of a 4-phenylethynyl (33–35) or 4-styryl group (32), unlike the case of dihydropyridines, greatly reduced affinity at A3 receptors, thus resulting in nonselectivity. Among 4-(phenylethynyl)pyridines, the presence of a 6-cyclobutyl or 6-cyclopentyl group, 34 or 35, respectively, did not affect the A3 receptor affinity observed for the corresponding 6-phenyl derivative, 33. The A3 adenosine receptor affinity of a 4-dimethoxy acetal pyridine derivative, 30, vs the corresponding 4-ethyl derivative, 25, was substantially decreased, while the change in affinity at A2A receptors was <2-fold. The corresponding aldehyde, 31, was weaker than the acetal, 30, at both A1 and A3 receptors.

The substituent at the 2-position also modulated adenosine receptor affinity. Among pyridine 3-ethyl esters, a 2-ethyl vs 2-methyl substituent afforded a 37-fold increase in A3 receptor affinity (36 vs 23), with little effect on affinity at A1 and A2A receptors. For 3-ethylthioesters in the pyridine series, a 2-ethyl vs 2-methyl substituent afforded a 2-fold increase in A2A and A3 receptor affinity (38 vs 26), and A1 receptor affinity was somewhat decreased. The corresponding 2-propyl pyridine analogue, 45, was intermediate in potency at A3 receptors. Due to the apparent favorable effect of alkyl groups larger than methyl at the 2-position, a variety of such substituents were examined. A 2-methoxyethyl group, in 46, favored affinity at human A3 receptors. 2-n-Butyl (47) and 2-cyclobutyl (48) groups resulted in 2-fold and 7-fold, respectively, lower A3 receptor affinity than the corresponding 2-ethyl analogue, 38. The most favorable 2-substituent, ethyl, was used in a series of analogues which probed optimization of 5- and 6-substituents (38–42). A 5-propyl ester, 39a, was 2-fold more potent than the corresponding 5-ethyl ester, 38; thus propyl appeared to be the favored 5-substituent among small alkyl esters. A 3-propyl thioester, 43, favored A3 receptor affinity. A 5-(2-hydroxyethyl) ester, 40, was synthesized for the purpose of increasing water solubility; however, affinity at human in A3 receptors was significantly decreased. At the 6-position, phenyl, 38, 3-chlorophenyl, 41, and cyclopentyl, 42, substituents were compared. A3 receptor affinity decreased in the order 3-chlorophenyl = phenyl ≫ cyclopentyl. 5-Propyl 2,4-diethyl-3-propylsulfanylcarbonyl-6-(m-chlorophenyl)-pyridine-5-carboxylate, 44, containing the optimized substitution was prepared and found to have a Ki value of 7.94 nM at human A3 receptors.

C. Potency and Selectivity of 1,4-Dihydropyridines and Pyridines at Rat A3 Receptors

At recombinant rat A3 receptors the binding affinities of selected derivatives were found to be in the micromolar range (Table 4). Generally, the pyridine derivatives reached higher affinity than the 1,4-dihydropyridines. Among 1,4-dihydropyridines, a 4-propyl, 12, or 5-benzyl ester group, 13, slightly increased A3 receptor affinity vs the corresponding 4,5-diethyl analogue, 10. Similar effects were observed at the human A3 receptor. Unlike at human A3 receptors, the presence of the 4-phenyl-ethynyl group in 17 was only slightly potency-enhancing. Like at human A3 receptors, a 2-ethyl group in 21 enhanced potency at rat A3 receptors by severalfold over the corresponding 2-methyl derivative, 10. A 2-propyl group, in the dihydropyridine 22, offered no advantage for A3 affinity over the 2-ethyl substituent.

Table 4.

Affinities of 4-Phenylethynyl-6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine Derivatives in Radioligand Binding Assays at Rat A3 Receptors

| compound |

Ki(μM)

|

rA3/hA3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rA3a | rA1/rA3 | ||

| 2 (MRS 1191) | 1.42 ± 0.19 | 28 | 45 |

| 10 | 4.60 ± 0.38 | 7.7 | 2.3 |

| 12 | 3.10 ± 0.78 | >20 | 1.4 |

| 13 | 2.80 ± 0.28 | >20 | 1.7 |

| 17 | 1.75 ± 0.18 | >40 | 78 |

| 21 | 2.52 ± 0.88 | >30 | 2.8 |

| 22 | 2.73 ± 0.14 | >30 | 1.3 |

| 26 | 1.47 ± 0.34 | 10 | 34 |

| 28 | 0.650 ± 0.070 | >100 | 3.4 |

| 29 | 1.80 ± 0.32 | >50 | 0.69 |

| 34 | 1.90 ± 0.42 | >50 | 0.79 |

| 38 | 0.410 ± 0.048 | >100 | 21 |

| 39a | 0.183 ± 0.033 | 42 | 22 |

| 39b (MRS 1523) | 0.113 ± 0.012 | 140 | 6.0 |

| 40 | 2.87 ± 0.48 | 6.1 | 15 |

| 41 | 0.440 ± 0.033 | 19 | 33 |

| 42 | 2.80 ± 0.22 | >20 | 0.83 |

| 43 | 0.294 ± 0.006 | 28 | 18 |

| 44 | 0.814 ± 0.037 | 50 | 100 |

| 45 | 0.590 ± 0.040 | 28 | 18 |

| 47 | 2.26 ± 0.05 | 18 | 64 |

Among pyridine derivatives binding at rat A3 receptors, unlike at human A3 receptors, a 4-propyl group, in 28, caused a 2-fold increase in affinity with a Ki value of 0.65 μM, vs the corresponding 3-ethyl analogue, 26. 5-Benzyl esters or substitutions with 4-phenylethynyl and 6-cyclobutyl groups, 29 and 34, did not significantly alter the affinity of 26. However, a 2-ethyl substitution increased the binding affinity at rat A3 receptors vs 26 by 4-fold, providing a Ki value of 0.41 μM. A 2-propyl pyridine analogue, 45, was near equipotent; however, a 2-butyl analogue, 47, was considerably less potent at rat A3 receptors.

5-Propyl 2-ethyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate, 39b, was prepared as an optimized ligand at rat A3 receptors, since the 4-propyl group was more favorable for affinity than the 4-ethyl group, and indeed 140-fold selectivity vs rat A1 receptors was achieved. This derivative was highly potent at both human and rat A3 receptors, with Ki values of 18.9 and 113 nM, respectively. In rat this corresponds to selectivities of 140- and 18-fold vs A1 and A2A receptors, respectively.

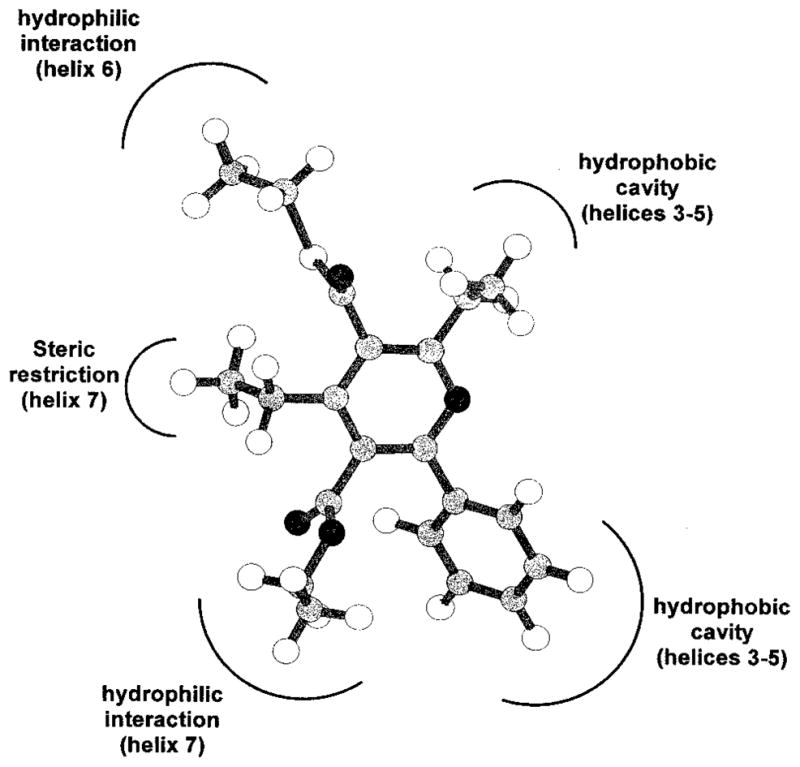

Molecular Modeling

By molecular modeling studies using RHF/AM1 semiempirical calculations and the steric and electrostatic alignment (SEAL) method, we offer a rationale for the high affinity of pyridine compounds at human A3 receptors. To propose structural analogies between these two classes of A3 ligands, we modeled the 1,4-dihydropyridine derivative 2 (MRS 1191), both R- and S-enantiomers, and the pyridine derivative 38. As reported above, 38 is among the most potent and selective pyridine-based ligands at human A3 receptors.

Pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine structures have high conformational flexibility, in particular regarding correspondence of the two ester groups at 3- and 5-positions. We have explored the conformational spaces for the three compounds, (R)-MRS 1191, (S)-MRS 1191, and 38. A complete random search conformational analysis was performed, and after sampling and minimization procedures, four energetically important conformers were selected for each studied compound (Table 5). The four conformers correspond to the structures in which the positions of the carbonyl of the 3- and 5-ester groups are up and/or down with respect to the plane of the pyridine or 1,4-dihydropyridine ring. The first important consideration is that the two enantiomers of MRS 1191 present conformers with different structures, in particular considering the spatial orientation of the two ester groups, as shown from the structural data collected in Table 5. The optimized structures for two of the conformers used in the overlay are shown in Figure 2.

Table 5.

Values for Enthalpy of Formation (ΔHf) and Spatial Arrangement (Dihedral Angle Values) of the 3- and 5-Ester Groups for the Energetically Important Conformers Calculated for 38, (R)-MRS 1191, and (S)-MRS 1191

| compd | no. | ΔHf, kcal/mola | 3-COORb | 5-COORb | ∠C2–C3–C–O (deg)c | ∠C6–C5–C–O (deg)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 1 | −82.4 | ↑ | ↑ | 79.5 | −88.9 |

| 2 | −81.9 | ↑ | ↓ | 78.6 | 90.7 | |

| 3 | −82.4 | ↓ | ↑ | −91.0 | −92.0 | |

| 4 | −81.9 | ↓ | ↓ | −89.6 | 93.0 | |

| (R)-MRS 1191 | 5 | −10.1 | ↑ | ↑ | 12.6 | −83.6 |

| 6 | −10.3 | ↑ | ↓ | 10.7 | 112.5 | |

| 7 | −8.9 | ↓ | ↑ | −89.5 | −84.3 | |

| 8 | −8.7 | ↓ | ↓ | −134.0 | 113.0 | |

| (S)-MRS 1191 | 9 | −8.8 | ↑ | ↑ | 146.8 | −100.8 |

| 10 | −9.3 | ↑ | ↓ | 148.1 | 60.3 | |

| 11 | −9.7 | ↓ | ↑ | −25.5 | −104.3 | |

| 12 | −10.3 | ↓ | ↓ | −21.9 | 61.8 |

Values calculated using RHF/AM1 Hamiltonian.

↑ and ↓ designations have been assigned using the chemical structural arrangement shown in Figure 2.

C and O atoms refer to the carbonyl moiety of the ester group.

Our hypothesis was that the receptor binding properties of 1,4-dihydropyridine and pyridine derivatives were due to recognition at a common region inside the receptor binding site and, consequently, a common electrostatic potential profile. The electrostatic potential profile is a function of the stereochemistry of the chiral center at the 4-position and the chemical structure of the conformer considered. To study the overall similarity between these two classes of A3 receptor ligands and to establish a quantitative comparison of the electrostatic potential fields, we have not used exact atomic matches, but rather the steric and electrostatic alignment (SEAL) method.25 The SEAL methodology has been developed to optimize the alignment of two three-dimensional structures using atomic charges and steric volume as factors. In this SEAL analysis we compared the 32 possible superimposition combinations between dihydropyridine/pyridine pairs for all 12 conformers listed in Table 5. From these structural alignments the best fit occurred between the (R) 3-down,5-up conformer of MRS 1191 and the 3-down,5-up conformer of 38, as illustrated in Figure 2. None of the (S) conformers overlap the pyridine structure with interaction energy comparable with the (R) 3-down,5-up conformer of MRS 1191. If there exists a correlation between thermodynamic binding constants and matching of the electrostatic potential fields of different antagonists, we can speculate that the (R) enantiomer of MRS 1191 could be more potent than the (S) enantiomer in A3 receptor binding. We, therefore, calculated the electrostatic contours for both the (R) 3-down,5-up conformer of MRS 1191 and the 3-down,5-up conformer of 38, as shown in Figure 2B. The electrostatic potential maps present complicated topologies; however, it is possible to identify several regions that show a high degree of similarity (Figure 3). The first two regions (negative electrostatic potential) are located around the carbonyl of the 3- and 5-ester groups. The second set designates the 1- and 6-positions corresponding to two hydrophobic regions (positive electrostatic potential). The last region corresponds to the π-systems of both pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine structures (negative electrostatic potential). Using both SEAL and electrostatic potential field analysis, it is possible to describe a pharmacophore map for these two classes of A3 antagonists. First of all, the stereochemistry of the chiral center seems to be important for the recognition process.11 Compound 38 and (R)-MRS 1191 present a high degree of similarity of the molecular charge distributions. Two important hydrophilic interactions, probably hydrogen-bonding interactions, could be involved between the two ester groups and polar amino acids in the binding cavity. A strong steric control around the 4-position of both 1,4-dihydropyridine and pyridine structures is suggested. In fact, bulky 4-position substituents, which are affinity-enhancing in the 1,4-dihydropyridines, are not well tolerated in the pyridine series. From a structural point of view, changing the C4-hybridization from sp3 to sp2, corresponding to the transformation of a 1,4-dihydropyridine to the corresponding pyridine, would change the C5–C4–R4 angle from 68.1° to 0.2°. A hydrophobic pocket is likely present around the 6-position where a phenyl ring would bind. Another important consideration is that the modification of the chemical properties of the nitrogen at the 1-position, from sp3 to sp2, and consequently the changing of the acid–base behavior of these compounds, does not prevent ligand recognition. These results can be summarized in a pharmacophore map as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scheme of the hypothetical pharmacophore map for compound 38. In brackets, the A3 receptor transmembrane helical domains putatively involved in the recognition of the pyridine moiety are shown.

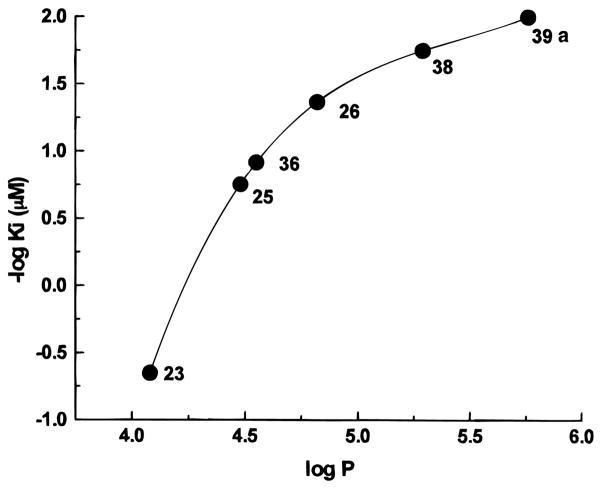

Moreover, a relationship was found for pyridine derivatives between affinity and hydrophobicity, represented by the log P value (Figure 5), such that A3 affinity in general increases with increasing log P values. Of course, we have to consider this correlation within the limitations of the specific steric requirements of the receptor binding site. Accordingly, the calculated log P values for the dihydropyridine 12, which contains a propyl group in place of ethyl in the 4-position, are higher with respect to 38 (5.02 and 4.88, respectively) but the Ki value is 2 orders of magnitude lower (2.17 and 0.0200 μM, respectively). In fact, as already mentioned, bulky substituents at the 4-position are not well tolerated in the pyridine series. Finally, values of calculated log P of 38 and MRS 1191, 5.29 and 4.98, respectively, are similar, as the compounds are similar in A3 affinity.

Figure 5.

Hydrophobicity structure–activity relationship found for the pyridine derivatives. The graph reports the correlation between the calculated log P values and the experimental value of log Ki of different pyridine compounds.

Discussion

Pyridine derivatives represent one of the possible important in vivo metabolites of 1,4-dihydropyridine compounds.24 The oxidation process produces three important chemical modifications in the 1,4-dihydropyridine structure: (a) the loss of the chiral center and consequently a change in the spatial position of the substituent in 4-position; (b) the formation of a stable aromatic system; and (c) the decrease of the pKa value. All of these factors can modify affinities and selectivities of pyridine compounds in comparison to the original properties of 1,4-dihydropyridines. The critical limitation in the quantitative interpretation of the SAR in the 1,4-dihydropyridine series is the limited chemical and pharmacological information about the two pure enantiomers. Since mainly racemic 1,4-dihydropyridines have been studied in adenosine receptor binding, correlating the experimental results with any structural properties is complicated. In the present study, we have reported that opportune combinations of substituents on the pyridine ring resulted in highly selective ligands for human A3 receptors. The discovery that pyridine derivatives can also bind to human A3 receptors could also be useful in modeling the mode of receptor binding of the 1,4-dihydropyridine compounds. Therefore, it was of interest to determine a hypothesis for a common mode of action of the pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives.

In the present study, we have compared the SAR of 1,4-dihydropyridines and the corresponding pyridine derivatives at human A3 receptors and at other adenosine receptors. Common substituents among A3 adenosine receptor-selective analogues in each series, such as 3,5-diesters, the 6-phenyl group, and small alkyl groups at the 2-position suggest a common receptor binding site for both substituted 1,4-dihydropyridine and pyridine derivatives. We have proposed a quantitative basis for this hypothesis using molecular modeling, although differences in the binding requirements of 1,4-dihydropyridines and pyridines have been found. For example, 6-cycloalkyl groups only in dihydropyridines but not pyridines favor A3 receptor affinity. Unlike the dihydropyridine derivatives, the 4-styryl and the 4-phenyl-ethynyl substituents are disfavored in A3 adenosine receptor binding of pyridines. At the 4-position of pyridines, an ethyl group was favored at human A3 receptors, and a propyl group favored at rat A3 receptors. At the 2-position, elongation of the 2-methyl substituent (but not beyond a 3-carbon chain) was found to enhance the affinity at A3 receptors. There is evidence (46) that an ether group within this chain is tolerated at human A3 receptors. Also, a 3-thioester group, which in dihydropyridine derivatives either enhanced A2A adenosine receptor affinity13 or had little effect on the adenosine receptor affinity (present study), in the pyridine series substantially enhanced A3 receptor affinity and selectivity. Thus, compound 26, containing a 2-methyl group, proved to be 340-fold selective for the human A3 receptor. The corresponding 2-ethyl analogue, 38, was >3000-fold selective for human A3 vs rat A1 receptors. The 5-benzyl ester did not enhance A3 receptor affinity of pyridines as it did for 4-(phenyl-ethynyl)dihydropyridines. In the dihydropyridine series, electron-withdrawing groups at the para and meta positions of a 5-benzyl ester provided A3 receptor selectivity of many thousand-fold, i.e., the affinity at A1 and A2A receptors was essentially negligible, and the affinity at A3 receptors vs 2 was either maintained or enhanced.13 Among the most selective compounds at human A3 receptors in the previous study was the 4-nitrobenzyl analogue, 3. In the present study the most potent pyridine derivatives at human A3 receptors were 44, 39a > 41 = 43, 46 > 38.

A persistent problem during the development of selective A3 receptor antagonists has been species differences in affinity.4 Affinity at rat A3 receptors is generally orders of magnitude lower than at human A3 receptors. This study has demonstrated that pyridine derivatives display considerable affinity and selectivity at rat A3 receptors (Table 4). Thus, certain compounds in this series having high affinity in both species, such as 39b, are likely to be of use as pharmacological probes across species. A detailed comparison between rat and human A3 receptor structures, using molecular modeling techniques, is in progress in our laboratory to explain the different SARs found for these two receptors.

In conclusion, the dihydropyridines and now the corresponding pyridines have served as structural scaffolds for enhancement of selectivity at human A3 receptors.17 An unsolved problem in the studies of dihydropyridines as A3 receptor antagonists is the resolution of enantiomers, since compounds 1–3 have as yet been characterized only as racemic compounds. The present study circumvents the need to resolve enantiomers, since we have demonstrated that derivatives highly selective for human A3 receptors may be obtained simply through oxidation of various 6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridines to the corresponding nonchiral pyridines. Functional studies and further optimization of the SAR in order to design radioligands and other affinity probes of the A3 receptor and to increase hydrophilicity are now appropriate. While the dihydropyridines such as MRS 1191 have been shown to be competitive antagonists,39 this remains to be demonstrated for the highly A3 receptor-selective pyridine derivatives reported here.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

Materials and Instrumentation

Ethyl 3-aminocrotonate (49c), aldehydes (50, except for 50d), ethyl acetoacetate (51a), ethyl propionylacetate (51b), tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (52), acrolein dimethyl acetal (53), ethyl benzoylacetate, 2,2,6-trimethyl-4H-1,3-dioxin-4-one (55), benzyl acetate, N-isopropylcyclohexylamine, all acid chlorides (56, except 56f, obtained by the reaction of the precursor acid with thionyl chloride), 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane-4,6-dione (57), ethanethiol, propanethiol, and Dowex 50×8-200 were purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 2-Methoxyethanethiol was prepared by a reported method.40 All other materials were obtained from commercial sources.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy was performed on a Varian GEMINI-300 spectrometer, and all spectra were obtained in CDCl3. Chemical shifts (δ) relative to tetramethylsilane are given. Chemical-ionization (CI) mass spectrometry was performed with a Finnigan 4600 mass spectrometer, and electron-impact (EI) mass spectrometry with a VG7070F mass spectrometer at 6 kV. Elemental analysis was performed by Atlantic Microlab Inc. (Norcross, GA). All melting points were determined with a Unimelt capillary melting point apparatus (Arthur H. Thomas Co., PA) and were uncorrected.

General Procedure for Preparation of Substituted 1,4-Dihydropyridine (8–14, 16–22, Scheme 1)

Equimolar amounts (0.5–1.0 mmol) of the appropriate β-enaminoester (49), aldehyde (50), and β-ketoester (51) were dissolved in 2–5 mL of absolute ethanol. The mixture was sealed in a Pyrex tube and heated, with stirring, to 80 °C for 18–24 h. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was purified by preparative TLC (silica 60; 1000 or 2000 μm; Analtech, Newark, DE; petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (4:1–9:1)). The products were shown to be homogeneous by analytical TLC and were stored at −20 °C.

3-Propyl 5-Ethyl 2,4-Dimethyl-6-phenyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (8)

1H NMR: δ 0.91 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.00 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.72 (m, 2 H), 2.30 (s, 3 H), 3.88–4.00 (m, 3 H), 4.15 (m, 2 H), 5.69 (s, br, 1 H), 7.28–7.31 (m, 2 H), 7.39–7.42 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 361 (M+ + NH4), 344 (M+ + 1). MS (EI): m/z 343 (M+), 328 (M+ – CH3, base), 314 (M+ – CH2CH3), 284 (M+ – OPr).

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-6-phenyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (9)

1H NMR: δ 0.87–0.92 (m, 6 H), 1.31 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.52 (m, 2 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H), 3.90 (m, 2 H), 4.03 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1 H), 4.20 (m, 2 H), 5.71 (s, br, 1 H), 7.30–7.40 (m, 5 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 361 (M+ + NH4, base), 344 (M+ + 1), 314 (M+ – C2H5). MS (EI): m/z 314 (M+-CH2CH3, base), 298 (M+ - OCH2CH3).

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-6-phenyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (10)

1H NMR: δ 0.90–0.96 (m, 6 H), 1.29 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.57 (m, 2 H), 2.33 (s, 3 H), 2.93 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.94 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.03 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.19 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 5.81 (s, br, 1 H), 7.30–7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.40–7.42 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 377 (M+ + NH4, base), 314 (M+ – OEt), 298 (M+ – SEt). MS (EI): m/z 330 (M+ – CH2CH3, base), 314 (M+- OEt), 298 (M+ - SEt), 286 (M+ - CO2Et).

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-6-phenyl-3-[(2-methoxy-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)]-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (11)

1H NMR: δ 0.91 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.60 (m, 2 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H), 3.14 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.38 (s, 3 H), 3.55 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.93 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.20 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.91 (s, br, 1 H), 7.28–7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.38–7.42 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 405 (M+ + NH4, base), 387 (M+).

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-propyl-6-phenyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (12)

1H NMR: δ 0.90 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.29 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.39 (m, 2 H), 1.49 (m, 2 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H), 2.92 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.92 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.19 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.98 (s, br, 1 H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 2 H), 7.38–7.41 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 391 (M+ + NH4, base), 373 (M+). MS (EI): m/z 330 (M+ – CH2CH2CH3, base), 314 (MH+ - OEt - Me), 284 (M+ - COSEt).

5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-6-phenyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (13)

1H NMR: δ 0.92 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.29 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.55–1.64 (m, 2 H), 2.32 (s, 3 H), 2.92 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.24 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.96 (AB, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H), 5.86 (s, br, 1 H), 6.98–7.00 (m, 1 H), 7.22–7.40 (m, 9 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 439 (M+ + NH4, base), 421 (M+), 360 (M+ – SEt).

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-6-phenyl-4-(dimethoxymethyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (14)

1H NMR: δ 0.91 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.33 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.33 (s, 3 H), 3.38 (s, 3 H), 3.39 (s, 3 H), 3.93 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.14 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.22 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.48 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 5.84 (s, br, 1 H), 7.31–7.35 (m, 2 H), 7.38–7.40 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 407 (M+ + NH4), 390 (M+ + 1), 358(M+ – OMe, base).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclopropyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (16)

1H NMR: δ 0.59 (m, 1 H), 0.88–1.03 (m, 2 H), 1.18–1.28 (m, 1 H), 1.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.31 (s, 3 H), 2.73–2.83 (m, 1 H), 4.17–4.35 (m, 2 H), 5.09 (s, 1 H), 5.29 (AB, J = 12.9 Hz, 2 H), 5.56 (s, br, 1 H), 7.22–7.47 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 441 (M+), 412 (M+ – CH2CH3,), 368 (M+ – CO2Et), 350 (M+ – CH2-Ph), 306 (M+ – CO2CH2Ph), 91 (+CH2Ph, base).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclobutyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (17)

1H NMR: δ 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.79–2.29 (m, 6 H), 2.37–2.40 (m, 1 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H), 4.21–4.27 (m, 2 H), 5.07 (s, 1 H), 5.26 (AB, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H), 6.10 (s, br, 1 H), 7.21–7.46 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 455 (M+), 426 (M+ – CH2CH3,), 382 (M+ – CO2Et), 364 (M+ – CH2Ph), 320 (M+ – CO2CH2Ph), 91 (+-CH2Ph, base).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclopentyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (18)

1H NMR: δ 1.23–1.37 (m, 4 H), 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.70 (m, 4 H), 2.00 (m, 1 H), 2.35 (s, 3 H), 4.24 (m, 2 H), 5.09 (s, 1 H), 5.27 (AB, J = 12.9 Hz, 2 H), 5.90 (s, br, 1 H), 7.22–7.46 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 487 (M+ + NH4), 470 (M+ + 1).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclohexyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (19)

1H NMR: δ 1.13–1.38 (m, 6 H), 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.65–1.89 (m, 5 H), 2.35 (s, 3 H), 4.22 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 5.09 (s, 1 H), 5.27 (AB, J = 12.6 Hz, 2 H), 5.99 (s, br, 1 H), 7.21–7.46 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 483 (M+), 454 (M+ – CH2CH3,), 400 (M+ – C6H11), 410 (M+ – CO2Et), 392 (M+ – CH2Ph), 348 (M+ - CO2CH2Ph), 91 (+CH2Ph, base).

3,5-Diethyl 2-Ethyl-6-phenyl-4-methyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (20)

1H NMR: δ 0.90 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.12 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.19 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.50 (m, 1 H), 2.90 (m, 1 H), 3.89–3.98 (m, 3 H), 4.22 (m, 2 H), 5.73 (s, br, 1 H), 7.30–7.31 (m, 2 H), 7.40–7.42 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 361 (M+ + NH4), 344 (M+ + 1). MS (EI): m/z 343 (M+), 328 (M+ – CH3, base), 298 (M+ – OEt).

5-Ethyl 2,4-Diethyl-6-phenyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (21)

1H NMR: δ 0.89 (m, 6 H), 0.93 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.19 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.58 (m, 2 H), 2.69 (m, 2 H), 2.92 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.92 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.02 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.94 (s, br, 1 H), 7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.41 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 391 (M+ + NH4, base), 374 (M+ + 1), 312 (M+ – SEt). MS (EI): m/z 373 (M+), 344 (M+ – CH2CH3), 328 (M+ – OEt, base), 312 (M+ –SEt).

5-Ethyl 2-Propyl-4-ethyl-6-phenyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-5-carboxylate (22)

1H NMR: δ 0.90–0.96 (m, 6 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.29 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.53–1.66 (m, 4 H), 2.66 (m, 2 H), 2.92 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.95 (q, J) 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.20 (t, J) 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.85 (s, br, 1 H), 7.30–7.32 (m, 2 H), 7.41–7.43 (m, 3 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 405 (M+ + NH4), 388 (M+ + 1), 326 (M+ – SEt).

Synthesis of Aldehyde Group Containing Dihydropyridine (15) (Scheme 2)

Dihydropyridine 14 (14 mg) and a catalytic amount of Dowex 50×8-200 resin were stirred in a mixture of acetone (2 mL) and water (0.5 mL) at room temperature for 48 h. The resin was filtered off, and the filtrate was dried with anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed, and the residue was purified with preparative TLC (silica 60; 1000 μm; Analtech, Newark, DE; petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (3:1)) to give 10 mg of the desired product (15), yield: 82%.

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-6-phenyl-4-formyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (15)

1H NMR: δ 0.89 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 3.94 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.24 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.90 (s, 1 H), 5.81 (s, br, 1 H), 7.35 (m, 2 H), 7.41 (m, 3 H), 9.66 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 361 (M+ + NH4), 344 (M+ + 1), 314 (M+ – CHO, base). MS (EI): m/z 343 (M+), 314 (M+ – CHO, base), 298 (M+ – OEt). HRMS: calcd for C18H20NO4 (M+ – CHO) 314.1392, found 314.1432.

General Procedure for Oxidation of 1,4-Dihydropyridines into Corresponding Pyridine Derivatives (Scheme 3)

Equimolar amounts of the 1,4-dihydropyridines (8–22, 53a–i, ~0.2 mmol) and tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (52) in THF (2–4 mL) were mixed and refluxed overnight. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, the solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by preparative TLC (silica 60; 1000 μm; Analtech, Newark, DE; petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (9:1–19:1)) to give the desired products.

3-Propyl 5-Ethyl 2,4-Dimethyl-6-phenylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (24)

1H NMR: δ 0.97–1.06 (m, 6 H), 1.81 (m, 2 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.35 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.43 (m, 3 H), 7.56–7.57 (m, 2 H). MS (EI): m/z 341 (M+), 312 (M+ – CH2CH3, base), 296 (M+ –OCH2CH3), 282 (M+ – OPr). HRMS: calcd for C20H23NO4 341.1627, found 341.1635.

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-6-phenylpyridine-3,5-di-carboxylate (25)

1H NMR: δ 0.97 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 1.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 2.71 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.09 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.46 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.43 (m, 3 H), 7.55–7.58 (m, 2 H). MS (EI): m/z 341 (M+), 312 (M+ – CH2CH3, base), 296 (M+ – OCH2CH3), 284 (MH+ – 2Et), 268 (M+ – CO2Et), 240 (MH+ –Et – CO2Et). HRMS: calcd for C20H23NO4 341.1627, found 341.1615.

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (26)

1H NMR: δ 0.97 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 2.74 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.09 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.56–7.59 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 375 (M+ + NH4), 358 (M+ + 1, base). MS (EI): m/z 357 (M+), 312 (M+ – OEt), 296 (M+ –SEt, base), 268 (M+ – COSEt).

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-3-[2-methoxyl-(ethylsulfanyl-carbonyl)]-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (27)

1H NMR: δ 0.97 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.62 (s, 3 H), 2.74 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.36 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.42 (s, 3 H), 3.67 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 4.09 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.39–7.42 (m, 3 H), 7.55–7.58 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 388 (M+ + 1), 296 (M+ - CH3OCH2CH2S).

5-Ethyl 2-Methyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (28)

1H NMR: δ 0.95 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 0.97 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.63 (m, 2 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 2.68 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.08 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.41 (m, 3 H), 7.56 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 372 (M+ + 1). MS (EI): m/z 326 (M+ – OCH2CH3), 310 (M+ – SEt, base), 282 (M+ –COSEt).

5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (29)

1H NMR: δ 1.18 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.40 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.60 (s, 3 H), 2.70 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.12 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 5.04 (s, 2 H), 6.96–6.98 (m, 2 H), 7.22–7.28 (m, 3 H), 7.38–7.40 (m, 3 H), 7.55–7.58 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 420 (M+ + 1, base).

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-4-(dimethoxymethyl)-6-phenylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (30)

1H NMR: δ 1.00 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.62 (s, 3 H), 3.33 (s, 6 H), 4.07 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.41 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 5.76 (s, 1 H), 7.40–7.42 (m, 3 H), 7.53–7.55 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 388 (M+ + 1). HRMS: calcd for C21H25NO6 387.1682, found 387.1674.

3,5-Diethyl 2-Methyl-4-formyl-6-phenylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (31)

1H NMR: δ 1.06 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.94 (s, 3 H), 4.17 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.42 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.43–7.45 (m, 3 H), 7.55 (m, 2 H), 8.63 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 342 (M+ + 1).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclobutylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (34)

1H NMR: δ 1.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.81–1.98 (m, 2 H), 2.11–2.19 (m, 2 H), 2.37–2.47 (m, 2 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 3.70 (m, 1 H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 5.39 (s, 2 H), 7.28–7.40 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 454 (M+ + 1).

3-Ethyl 5-Benzyl 2-Methyl-4-phenylethynyl-6-cyclopentylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (35)

1H NMR: δ 1.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.54–1.58 (m, 2 H), 1.78–1.88 (m, 6 H), 2.57 (s, 3 H), 3.04 (m, 1 H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 5.41 (s, 2 H), 7.29–7.44 (m, 10 H). MS (EI): m/z 467 (M+), 376 (M+ – CH2Ph), 91 (+CH2Ph, base).

3,5-Diethyl 2-Ethyl-4-methyl-6-phenylpyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (36)

1H NMR: δ 1.00 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.33 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.42 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.36 (s, 3 H), 2.86 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.12 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.45 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.43 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.60 (m, 2 H). MS (EI): m/z 341 (M+), 312 (M+ – CH2CH3, base), 296 (M+ – OEt), 284 (MH+ – 2Et), 269 (MH+ – CO2Et). HRMS: calcd for C20H23NO4 341.1627, found 341.1631.

2-Methyl-4-ethyl-5-ethoxycarbonyl-6-phenylpyridine-3-carboxylic Acid (37)

1H NMR: δ 0.97 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.61 (s, 3 H), 2.71 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.46 (J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.45 (m, 3 H), 7.55–7.59 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 314 (M+ + 1). MS (EI): m/z 312 (M+ – 1), 296 (M+ – OH), 284 (M+ – Et, base).

5-Ethyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (38)

1H NMR: δ 0.98 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.73 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.61 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 372 (M+ + 1, base).

5-Propyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (39a)

1H NMR: δ 0.65 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34–1.44 (m, 2 H), 2.73 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.59–7.62 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 404 (MH+ + NH4), 386 (M+ + 1, base).

5-Propyl 2-Ethyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (39b)

1H NMR: δ 0.66 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 0.95 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.40 (m, 2 H), 1.63 (m, 2 H), 2.66 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.86 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.13 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.39–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.62 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 400 (M+ + 1, base).

5-Hydroxylethyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (40)

1H NMR: δ 1.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.75 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.15 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.48 (m, 2 H), 4.13 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.45–7.49 (m, 3 H), 7.60–7.63 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 404 (M+ + NH4 – 1), 388 (M+ + 1).

5-Ethyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-(m-chlorophenyl)pyridine-5-carboxylate (41)

1H NMR: δ 1.07 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.72 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.86 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.35–7.41 (m, 1 H), 7.46–7.50 (m, 1 H), 7.62 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 406 (M+ + 1).

5-Ethyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-cyclopentylpyridine-5-carboxylate (42)

1H NMR: δ 1.18 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.63 (m, 2 H), 1.92 (m, 7 H), 2.58 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.76 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.91 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.40 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H). HRMS: calcd for C20H29NO3S 363.1868, found 363.1858.

5-Ethyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-propylsulfanylcarbonyl-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (43)

1H NMR: δ 0.98 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.07 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.76 (m, 2 H), 2.73 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.87 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.12 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.42–7.43 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.61 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 386 (M+ + 1, base).

5-Propyl 2,4-Diethyl-3-propylsulfanylcarbonyl-6-(m-chlorophenyl)pyridine-5-carboxylate (44)

1H NMR: δ 0.72 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.07 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.34 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.46 (m, 2 H), 1.77 (m, 2 H), 2.72 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.86 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.13 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.04 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.37 (m, 2 H), 7.48 (m, 1 H), 7.62 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 434 (M+(C23H28-35ClNO3S) + 1, base), 404 (M+ – C2H5), 358 (M+ – PrS).

5-Ethyl 2-Propyl-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (45)

1H NMR: δ 0.99 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.82 (m, 2 H), 2.72 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.81 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.14 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.57–7.60 (m, 2 H). MS (EI): m/z 385 (M+), 340 (M+ – OEt), 324 (M+ – SEt), 296 (M+ – COSEt).

5-Ethyl 2-(2-Methoxylethyl)-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (46)

1H NMR: δ 0.99 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.73 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.11–3.18 (m, 4 H), 3.37 (s, 3 H), 3.85 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.42–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.61 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 402 (MH+, base). HRMS: calcd for C22H27NO4S 401.1661, found 401.1666.

5-Ethyl 2-Butyl-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (47)

1H NMR: δ 0.93 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.28–1.39 (m, 2 H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.77 (m, 2 H), 2.72 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.83 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.13 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.40–7.43 (m, 3 H), 7.58–7.60 (m, 2 H). MS(CI/NH3): m/z 400 (M+ + 1, base). MS (EI): m/z 400 (M+ + 1), 371 (MH+ – Et), 338 (M+ – SEt, base). HRMS: calcd for C23H29NO3S 399.1868, found 399.1867.

5-Ethyl 2-Cyclobutyl-4-ethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate (48)

1H NMR: δ 1.00 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.86–1.95 (m, 1 H), 1.95–2.05 (m, 1 H), 2.17–2.56 (m, 2 H), 2.51–2.64 (m, 2 H), 2.70 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.13 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.79 (m, 1 H), 4.11 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.42–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.67–7.69 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 398 (M+ + 1, base).

General Procedure for Preparation of β-Amino-α,β-unsaturated Esters (Scheme 4)

A β-ketoester (3 mmol) and ammonium acetate (4.5 mmol) were mixed in 5 mL of absolute ethanol and refluxed at 80 °C for 24 h. The solvent was removed, and the residue was chromatographed to give the desired compounds in moderate yields.

Ethyl 3-Amino-3-phenyl-2-propenoate (49a)

1H NMR: δ 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 4.18 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.97 (s, 1 H), 7.41–7.53 (m, 3 H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 2 H).

Benzyl 3-Amino-3-phenyl-2-propenoate (49b)

1H NMR: δ 4.97 (s, ¼ H), 5.05 (s, ¾ H), 5.18 (s, 2 H), 7.29–7.56 (m, 10H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 272 (M+ + NH4), 254 (M+ + 1, base).

Propyl 3-Amino-3-phenyl-2-propenoate (49d)

1H NMR: δ 0.98 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.70 (m, 2 H), 4.09 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.99 (s, 1 H), 7.39–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 206 (M+ + 1, base).

Hydroxylethyl 3-Amino-3-phenyl-2-propenoate (49e)

1H NMR: δ 3.87 (m, 2 H), 4.28 (m, 2 H), 5.02 (s, 1 H), 7.43–7.47 (m, 3 H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 208 (M++ 1, base), 192 (MH+ - NH2).

Ethyl 3-Amino-3-(m-chlorophenyl)-2-propenoate (49f)

1H NMR: δ 1.30 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 4.18 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.95 (s, 1 H), 7.35–7.44 (m, 3 H), 7.54 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 226 (C11H1235ClNO2, M+ + 1, base), 227 (M+, C11H12-37ClNO2).

Ethyl 3-Amino-3-cyclopentyl-2-propenoate (49g)

1H NMR: δ 1.27 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.54–1.81 (m, 6 H), 1.89–1.94 (m, 2 H), 2.50 (m, 1 H), 4.11 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.60 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 184 (M+ + 1, base).

Propyl 3-Amino-3-(m-chlorophenyl)-2-propenoate (49h)

1H NMR: δ 0.98 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.69 (m, 2H), 4.09 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.96 (s, 1 H), 7.32–7.45 (m, 3 H), 7.54 (s, 1 H). MS(CI/NH3): m/z 240 (C12H1435ClNO2, M+ + 1, base). MS (EI): m/z 239 (M+), 223 (M+ – NH2), 180 (M+ – PrO), 153 (M+ – 1 – CO2Pr, base).

Preparation of 2,2-Dimethoxylacetaldehyde (50d, Scheme 5)41

Literature procedure was followed with some modifications. Potassium permanganate (16 g, 100 mmol) in 300 mL of water was added slowly to a vigorously stirred ice-cooled suspension of 10.2 g (100 mmol) of acrolein dimethyl acetal in 120 mL of water. The speed of addition was controlled to keep the temperature as near to 5 °C as possible. Soon after the stirring stopped, the mixture formed a gel. After 2 h of standing, the mixture was heated at 95 °C for 1 h and then filtered. Upon cooling, the filtrate was treated with 240 g of anhydrous K2CO3. The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with ethyl acetate (80 mL × 5). Organic phases were combined and dried with anhydrous MgSO4. After the solvent was removed, a colorless oil (6.84 g, yield: 50%) remained and was used directly for the next reaction, identified as dl-glyceraldehyde dimethyl acetal (54). 1H NMR: δ 2.44 (s, br, 1 H), 2.73 (s, br, 1 H), 3.48 (s, 6 H), 3.69–3.73 (m, 3 H), 4.36 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H). MS (CI/NH3): m/z 154 (M+ + NH4, base).

Compound 54 (2.11 g, 15.5 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of dichloromethane (100 mL) and water (5 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. While stirring, sodium periodate (7.5 g, 35 mmol) was carefully added in three portions within 30 min. After an additional 1 h of stirring at room temperature, anhydrous MgSO4 (14 g) was added to the reaction mixture, and stirring was continued for an additional 0.5 h. The reaction was then filtered. Removal of the solvent left 1.38 g of the desired product, 50d, yield: 85%. 1H NMR: δ 3.46 (s, 6 H), 4.50 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 9.48 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H).

Synthesis of β-Ketoesters 51c,d,g,j,k,u (Scheme 6)

β-Ketoester 51c and β-ketothioesters 51d and 51g were prepared by the reaction of 2,2,6-trimethyl-4H-1,3-dioxin-4-one (55) and an alcohol or a thiol (eq 1). Equimolar amounts (for example, 3 mmol) of compound 55 and an alcohol or a thiol were heated with a little toluene (1–2 mL) at 100 °C in a sealed tube overnight. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was chromatographed to give the desired products in satisfactory yields (64% for 51c, 97% for 51d, and 67% for 51g).

Propyl Acetoacetate (51c)

1H NMR: δ 0.94 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.66 (m, 2 H), 2.27 (s, 3 H), 3.46 (s, 2 H), 4.09 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H).

S-Ethyl 3-Oxothiobutyrate (51d)

1H NMR: δ 1.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.27 (s, 3 H), 2.94 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.67 (s, 2 H).

S-(2-Methoxylethyl) 3-Oxothiobutyrate (51g)

1H NMR: δ 2.27 (s, 3 H), 3.15 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.37 (s, 3 H), 3.55 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.69 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH3): 194 (M+ + NH4, base), 176 (M+).

β-Ketoesters 51j and 51k were prepared by a route shown in eq 2. N-Isopropylcyclohexylamine (0.786 g, 5.5 mmol) and n-BuLi (2.2 mL, 5.5 mmol, 2.5 N in hexanes) were mixed at 0 °C in 15 mL of THF for 15 min. The temperature was then lowered to −78 °C. Benzyl acetate (0.752 g, 0.72 mL, 5 mmol) was then added slowly into this system, and the mixture was stirred for 10 min at the same temperature to form an enolate. Cyclohexanecarbonyl chloride (0.806 g, 0.74 mL, 5.5 mL, for 51k) or cyclopentanecarbonyl chloride (0.729 g, 0.67 mL, 5.5 mmol, for 51j) was added dropwise to this enolate solution within 10 min. After 15 min of stirring, the reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and poured into 10 mL of 1 N HCl. The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted with ether (10 mL × 3). The combined organic phases were washed with 1 N NaHCO3 (10 mL) and water (10 mL) and then dried with anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed, and the residue was chromatographed (silica 60, petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (9:1)) to give 130 mg of 51k (yield: 10%) or 569 mg of 51j (yield: 46%).

Benzyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclopentylpropionate (51j)

1H NMR: δ 1.19–1.81 (m, 8 H), 2.76–2.85 (m, 1 H), 3.55 (s, 2 H), 5.11 (s, 2 H), 7.31–7.36 (m, 5 H).

Benzyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclohexylpropionate (51k)

1H NMR: δ 1.20–1.51 (m, 5 H), 1.66–1.96 (m, 5 H), 2.25–2.38 (m, 1 H), 3.51 (s, 2 H), 5.19 (s, 2 H), 7.37 (m, 5 H).

To prepare compound 51u, a transesterification reaction was used (eq 3). Ethyl benzoyl acetate (1.92 g, 10 mmol) and ethylene glycol (0.621 g, 10 mmol) in toluene (10 mL) were heated with stirring for 24 h. The solvent was removed, and the residue was chromatographed (silica 60, petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (3:1)) to give 0.946 g of the desired product, yield: 45%.

Hydroxylethyl Benzoylacetate (51u)

1H NMR: δ 2.52 (s, br, 1 H), 3.4 (m, 2 H), 4.08 (s, 2 H), 4.35 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 7.43–7.53 (m, 2 H), 7.60–7.65 (m, 1 H), 7.93–7.96 (m, 2 H).

Synthesis of β-Ketoesters 51e,f,h,i,l–n,p–t via Meldrum’s Acids (Scheme 7)42

The preparation of S-ethyl 3-oxothiovalerate (51e) is provided as an example. 2,2-Dimethyl-1,3-dioxane-4,6-dione (57, 0.721 g, 5 mmol) and propionyl chloride (0.509 g, 5.5 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of dry CH2Cl2. At 0 °C, 0.81 mL (0.791 g, 10 mmol) of pyridine (in the cases of aromatic acid chlorides, using 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine instead of pyridine) was then added dropwise. The reaction temperature was kept at 0 °C for 1 h and then raised to room temperature for an additional h. The reaction mixture was washed with 1 N HCl (10 mL) and water (5 mL) and then dried with anhydrous MgSO4. Removal of the solvent left the desired product (58e), which was directly used for the next reaction without purification.

Compound 58e (670 mg, 3.35 mmol) and ethanethiol (0.621 g, 10 mmol) were mixed in 10 mL of toluene. This mixture was heated at 80 °C in a flask with an effective flux condenser for 24 h. The solvent and excess ethanethiol were removed, and the residue was chromatographed (silica 60, petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (9:1)) to give the desired product, 282 mg, yield: 53%.

S-Ethyl 3-Oxothiovalerate (51e)

1H NMR: δ 1.07 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.28 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 2.58 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.94 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 3.66 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 178 (M+ + NH4), 161 (M+ + 1).

S-Ethyl 3-Oxothiocaproate (51f)

1H NMR: δ 0.92 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.62 (m, 2 H), 2.53 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.93 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.65 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 192 (M+ + NH4, base), 175 (M+ + 1).

Benzyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclopropylpropionate (51h)

1H NMR: δ 0.90–0.96 (m, 2 H), 1.08–1.13 (m, 2 H), 1.98–2.05 (m, 1 H), 3.62 (s, 2 H), 5.20 (s, 2 H), 7.30–7.39 (m, 5 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 236 (M+ + NH4, base), 219 (M+ + 1).

Benzyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclobutylpropionate (51i)

1H NMR: δ 1.59–2.37 (m, 6 H), 3.37 (m, 1 H), 3.45 (s, 2 H), 5.17 (s, 2 H), 7.34–7.37 (m, 5 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 250 (M+ + NH4, base), 233 (M+ + 1).

S-Ethyl 3-Oxothioheptanoate (51l)

1H NMR: δ 0.91 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.51–1.62 (m, 4 H), 2.55 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.93 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.65 (s, 2H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 206 (M+ + NH4, base).

S-Propyl 3-Oxothiovalerate (51m)

1H NMR: δ 0.98 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.07 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.62 (m, 2 H), 2.58 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.91 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.67 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 175 (M+ + 1).

S-Ethyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclobutylthiopropionate (51n)

1H NMR: δ 1.27 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.85 (m, 1 H), 1.93–2.05 (m, 1 H), 2.14–2.31 (m, 4 H), 2.92 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.42 (m, 1 H), 3.61 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 204 (M+ + NH4, base), 187 (M+ + 1).

S-Ethyl 3-Oxo-5-methoxythiovalerate (51p)

1H NMR: δ 1.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 2.80 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.93 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.34 (s, 3 H), 3.65 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.71 (s, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 208 (M+ + NH4, base), 191 (M+ + 1).

Ethyl 3-Oxo-3-cyclopentylpropionate (51q)

1H NMR: δ 1.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.59–1.71 (m, 2 H), 1.76–1.88 (m, 2 H), 2.98 (m, 1 H), 3.49 (s, 2 H), 4.19 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 202 (M+ + NH4, base).

Propyl Benzoylacetate (51r)

1H NMR: δ 0.95 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 1.64–1.71 (m, 2 H), 3.39 (s, 2 H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.47–7.97 (m, 5 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 224 (M+ + NH4, base), 206 (M+).

Ethyl m-Chlorobenzoylacetate (51s)

1H NMR: δ 1.26 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H), 3.91 (s, 2 H), 4.22 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.36–7.84 (m, 3 H), 7.93 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 244 (C11H1135ClO3, M+ + NH4, base), 227 (C11H1135ClO3, M+ + 1).

Propyl m-Chlorobenzoylacetate (51t)

1H NMR: δ 0.90 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.64 (m, 2 H), 3.98 (s, 2 H), 4.12 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 7.36–7.84 (m, 3 H), 7.93 (s, 1 H). MS (CI/NH4): m/z 258 (C11H1135ClO3, M+ + NH4, base), 241 (C11H1135ClO3, M+ + 1).

Computational Methodologies

Compound 38, (R)-MRS 1191, and (S)-MRS 1191 models were constructed using the “Sketch Molecule” of SYBYL.26 These structures were fully minimized using MOPAC software27 (RHF method and AM1 Hamiltonian,28 keywords: PREC, GNORM=0.1, EF).

Conformational analysis of 38, (R)-MRS 1191, and (S)-MRS 1191 derivatives was performed on all rotatable bonds of the pyridine or 1,4-dihydropyridine substituents using the random search procedure of SYBYL. The optimized geometries of the resulting conformers were calculated using MOPAC software (RHF method and AM1 Hamiltonian, keywords: PREC, GNORM=0.1, EF).

Partial atomic charges for the calculation of the electrostatic potential maps were obtained using RHF/3-21G(*)//RHF/AM1 ab initio level29 of Gaussian 94.30 Atomic charges were calculated by fitting to electrostatic potential maps (CHELPG method).31 Electrostatic contours were generated using standard procedures within SYBYL.

All calculations were performed on a Silicon Graphics Indigo 2 R8000 workstation.

Steric and electrostatic alignment (SEAL) method25 was used to optimize the superimposition between pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives using PowerFit v.1.0 program.32 Starting with 100 random orientations, SEAL utilized the steric volume and the atomic partial charges of two molecular structures in a determination of their optimal alignment. SEAL setup parameters for pyridine and 1,4-dihydropyridine alignments included α = 0.5, WS = 1, WE = 1, and specification for the Gaussian attenuation function.

log P values (the log of the octanol–water partition coefficient), a hydrophobicity indicator, were empirically calculated using the atom fragment method developed by Ghose, Pritchett, and Crippen33 and implemented in ChemPlus v.1.0.34 ChemPlus is an extension of Hyperchem for Windows. Both SEAL alignments and log P calculations were performed on a PC Pentium 166 MHz.

Pharmacology

Radioligand Binding Studies

Binding of [3H]R-N6-phenylisopropyladenosine ([3H]R-PIA) to A1 receptors from rat cerebral cortex membranes and of [3H]-2-[4-[(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarbamoyladenosine ([3H]CGS 21680) to A2A receptors from rat striatal membranes was performed as described previously.35,36 Adenosine deaminase (3 units/mL) was present during the preparation of the brain membranes, in a preincubation of 30 min at 30 °C, and during the incubation with the radioligands.

Binding of [125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine ([125I]AB-MECA) to membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing the human A3 receptor, clone HS-21a (Receptor Biology, Inc., Baltimore MD) or to membranes prepared from CHO cells stably expressing the rat A3 receptor was performed as described.9,37 The assay medium consisted of a buffer containing 10 mM Mg2+, 50 mM Tris, and 1 mM EDTA, at pH 8.0. The glass incubation tubes contained 100 μL of the membrane suspension (0.3 mg protein/mL, stored at −80 °C in the same buffer), 50 μL of [125I]AB-MECA (final concentration 0.3 nM), and 50 μL of a solution of the proposed antagonist. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM N6-phenylisopropyladenosine (R-PIA).

All nonradioactive compounds were initially dissolved in DMSO and diluted with buffer to the final concentration, where the amount of DMSO never exceeded 2%.

Incubations were terminated by rapid filtration over Whatman GF/B filters, using a Brandell cell harvester (Brandell, Gaithersburg, MD). The tubes were rinsed three times with 3 mL of buffer each.

At least five different concentrations of competitor, spanning 3 orders of magnitude adjusted appropriately for the IC50 of each compound, were used. IC50 values, calculated with the nonlinear regression method implemented in the InPlot program (Graph-PAD, San Diego, CA), were converted to apparent Ki values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation38 and Kd values of 1.0 nM ([3H]R-PIA); 14 nM ([3H]CGS 21680); 0.59 nM and 1.46 nM ([125I]AB-MECA at human and rat A3 receptors, respectively).

Acknowledgments

We thank Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA) for financial support to S.M. We thank Prof. Gary L. Stiles and Dr. Mark E. Olah (Duke University, Durham, NC) for providing samples of [125I]I-AB-MECA and cells expressing recombinant rat A3 receptors and Nancy Forsythe for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- [125I]AB-MECA

[125I]N6-(4-amino-3-iodo-benzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine

- CGS 21680

2-[4-[(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl]ethyl-amino]-5′-N-ethylcarbamoyladenosine

- CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- DMAPN

N-(dimethylamino)pyridine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPPA

diphenylphosphoryl azide

- EDAC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- HEK cells

human embryonic kidney cells

- IB-MECA

N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine

- Ki

equilibrium inhibition constant

- log P

log of the octanol–water partition coefficient

- MRS 1191

3-ethyl 5-benzyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate

- MRS 1476

5-ethyl 2,4-diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate

- R-PIA

R-N6-phenylisopropyladenosine

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SEAL

steric and electrostatic alignment

- TBAF

tetrabutylammonium fluoride

- Tris

tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

References

- 1.Jacobson KA, van Rhee AM. Purinergic Approaches in Experimental Therapeutics. In: Jacobson KA, Jarvis MF, editors. Development of selective purinoceptor agonists and antagonists. Chapter 6. Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramkumar V, Stiles GL, Beaven MA, Ali H. The A3 adenosine receptor is the unique adenosine receptor which facilitates release of allergic mediators in mast cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16887–16890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali H, Choi OH, Fraundorfer PF, Yamada K, Gonzaga HMS, Beaven MA. Sustained activation of phospholipase-D via adenosine A3 receptors is associated with enhancement of antigen-ionophore-induced and Ca2+-ionophore-induced secretion in a rat mast-cell line. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson KA. A3 adenosine receptors: Novel ligands and paradoxical effects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RCS, Popik P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]