Abstract

Cattle death by starvation is a persistent annual event in Manitoba. Herds with more than 10% overwinter death loss are usually identified in the late winter or early spring. Field and postmortem findings suggest that there is complete mobilization of fat followed by inability to maintain adequate thermoregulation and death by cardiac arrest. Carcasses show only mild evidence of muscle catabolism and are in excellent preservation if located prior to or around the time of spring thaw. A forensic diagnosis of death by starvation-induced exposure can be made with a high level of confidence when considering field data, whole carcass appearance, and postmortem evaluation of residual fat stores.

Résumé

Modèle explicatif de la mort de bovins par inanition au Manitoba : évaluation médico-légale. La mort de bovins par inanition est une occurrence annuelle constante au Manitoba. Les troupeaux ayant plus de 10 % de mortalités pendant l’hiver sont habituellement identifiés à la fin de l’hiver ou au début du printemps. Les résultats sur le terrain et lors des autopsies suggèrent que la mort est causée par une mobilisation complète des graisses suivie d’une incapacité à maintenir une thermorégulation adéquate et de la mort par arrêt cardiaque. Les carcasses présentent seulement des preuves faibles de catabolisme musculaire et sont très bien préservées si elles sont repérées avant ou vers le moment du dégel printanier. Un diagnostic médico-légal de mort par exposition induite par inanition peut être posé avec un niveau de confiance élevé lorsque l’on considère les données sur le terrain, l’apparence des carcasses entières et l’évaluation des graisses résiduelles à l’autopsie.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

This paper proposes a patho-physiologic model for the progression of bovine starvation in Manitoba/cold climates: i) prolonged starvation results in weak animals in body condition score (BCS) 1, which become recumbent to conserve metabolic resources; ii) once recumbent the core body temperature starts to drop, decreasing the efficiency of skeletal muscle making it difficult to regain the standing position; iii) rumen microflora die en masse at some core body temperature above 28°C, preventing postmortem bloat; iv) when core body temperature decreases to about 21°C to 20°C the heart becomes asystolic and the animal dies.

Located above the 49th parallel in the center of the North American continent, the climate of Manitoba is extreme. In general, temperatures and precipitation decrease from south to north, and precipitation also decreases from east to west. Since Manitoba is far removed from the moderating influences of both mountain ranges and large bodies of water, and because of the flat landscape in many areas, the province is exposed to numerous weather systems throughout the year, including cold Arctic high-pressure air masses that settle in from the northwest, usually during January and February. The beef cattle production area of southern Manitoba (including Winnipeg), falls into the humid continental climate zone (Koppen Dfb) with average daily January temperatures of −13°C to −23°C (daytime high/nighttime low) (1).

The provincial veterinary infrastructure has been serving as the primary police functionaries in animal neglect situations in Manitoba for many years under various statutes and with clearer direction since 1998 with the introduction of The Animal Care Act. Over the past years veterinary officers employed by the provincial Chief Veterinary Office (CVO), have had many opportunities to observe winter die-off (Table 1). Some cases of significant die-off in beef cattle herds are reported to the authorities. General response is to use veterinary officers to evaluate the situation; where starvation is suspected, the surviving cattle are removed to a facility where they can be assigned a BCS and supplied with adequate nutrition. A representative number of carcasses are removed for complete postmortem and forensic evaluation at the provincial Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

Table 1.

Major demographics of selected case files of beef cattle winter kill in Manitoba

| Case number | Date identified | Number of cattle found alive | Number of cattle found dead | Number of cattle killed on farm or dying in the next 7 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003-01-021 | Jan 24, 2003 | 128 | 44 | 7 |

| 2004-01-028 | Jan 26, 2004 | 150 | 12 | 0 |

| 2004-02-067 | Feb 19, 2004 | 38 | 5 | 3 |

| 2004-02-070 | Feb 25, 2004 | 120 | 21 | 0 |

| 2005-01-005 | Jan 5, 2005 | 46 | 25 | 0 |

| 2005-03-054 | Mar 21, 2005 | 86 | 110 | 0 |

| 2006-04-073 | April 26, 2006 | 12 | 25 | 0 |

| 2007-02-045 | Feb 2, 2007 | 188 | 22 | 2 |

| 2007-02-064 | Mar 15, 2007 | 168 | 42 | 3 |

| 2007-03-085 | Mar 14, 2007 | 117 | 43 | 2 |

| 2007-04-107 | Apr 5, 2007 | 10 | 12 | 0 |

| 2008-04-058 | Apr 4, 2008 | (230) | 98 | 0 |

| 2009-05-133 | May 22, 2009 | (80) | 38 | 0 |

| 2010-03-071 | Mar 20, 2010 | 55 | 18 | 0 |

| 2011-01-032 | Jan 27, 2011 | 35 | 7 | 7 |

| 2011-05-144 | May 2, 2011 | (35) | 5 | 1 |

| 2011-05-156 | May 11, 2011 | 52 | 67 | 5* |

| 2011-05-165 | May 15, 2011 | 48 | 61 | 0 |

Average age of 12 producers was 64 + 11 y (Min 47, Max 80), at the time of the incident. (Estimated Number), cattle not processed through a handling facility.

Newborn or neonatal calves.

For the purposes of this review “winter starvation” cases are defined by i) death loss in individuals of more than 6 mo of age in excess of 10% of the fall herd of cattle; ii) where death occurred after December 1st and before May 1st of the following year; iii) the carcasses are visually consistent with pre-mortem emaciation; and iv) the surviving cattle have an individual average BCS < 3 on the Wagner scale for Hereford cattle: very thin, no palpable or visible fat on ribs or brisket, individual muscles in the hind quarter are easily visible, and spinous processes are very apparent (Table 2) (2). The 10% cut-off is arbitrary, and used in the administration of The Animal Care Act to identify cases egregious enough to warrant additional (limited) resources for prosecution. In this paper we use emaciation to mean severe to complete loss of body fat stores in contrast to cachexia, where in addition to complete body fat depletion there is also significant muscle atrophy or catabolism.

Table 2.

Wagner Body Condition Scoring System (reproduced from reference 2)

| Score | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Severely emaciated. All ribs and bone structure easily visible and physically weak. Animal has difficulty standing or walking. No external fat present by sight or touch. |

| 2 | Emaciated. Similar to 1 but not weakened. |

| 3 | Very thin. No palpable or visible fat on ribs or brisket. Individual muscles in the hind quarter are easily visible and spinous processes are very apparent. |

| 4 | Thin. Ribs and pin bones are easily visible and fat is not apparent by palpation on ribs or pin bones. Individual muscles in the hind quarter are apparent. |

| 5 | Moderate. Ribs are less apparent than in 4 and have less than 0.5 cm of fat on them. Last two or three ribs can be felt easily. No fat in the brisket. At least 1 cm of fat can be palpated on pin bones. Individual muscles in hind quarter are not apparent. |

| 6 | Good. Smooth appearance throughout. Some fat deposition in brisket. Individual ribs are not visible. About 1 cm of fat on the pin bones and on the last 2 to 3 ribs. |

| 7 | Very good. Brisket is full, tailhead and pin bones have protruding deposits of fat on them. Back appears square due to fat. Indentation over spinal cord due to fat on each side. Between 1 and 2 cm of fat on last 2 to 3 ribs. |

| 8 | Obese. Back is very square. Brisket is distended with fat. Large protruding deposits of fat on tailhead and pin bones. Neck is thick. Between 3 and 4 cm of fat on last 2 to 3 ribs. Large indentation over spinal cord. |

| 9 | Very obese. Description of 8 taken to greater extremes. |

Starvation

Research reports which explore the physiologic mechanisms, duration, and the process of starving commercial farm animals to death are rare. One study in swine identified 3 types of starvation: i) complete removal of both feed and water; ii) normal access to feed with complete water restriction; and iii) complete feed restriction with free access to water. The end point of the experiment was animal death. Pigs allowed feed without water died in about 15.5 d with limited variability and death attributed to entero-intoxication; with complete removal of both feed and water pigs survived to 21 to 28 d with greater variability; and pigs provided no feed but access to water survived the longest, between 36 and 89 d depending on their pre-starvation adiposity (3). In rabbits fed 20% of their normal ration for 4 mo, animals could lose 40% of their body mass and develop gelatinous transformation of their bone marrow (4). Losses in body mass and normal bone marrow were reversed by feeding appropriate volumes of balanced rabbit ration. The re-feeding of severely starved otherwise healthy horses has met with mixed success both without cold stress (5) and with moderate cold stress (6). In both studies a proportion of individual horses died in the face of re-feeding.

Late winter starvation has been well-documented in farmed reindeer. Winter starvation in farmed reindeer manifests as “complete emaciation” with severe muscle atrophy, with serous atrophy of subepicardial and bone marrow fat (7). In reindeer displaying both emaciation and cachexia the deaths are attributed to exhaustion of energy reserves. During 1988, subsequent to pasture reduction by fencing, 30% of a population of about 1000 feral cattle died from starvation on Amsterdam Island (Indian Ocean); 90.8% of deaths occurred from July to October which are the winter months in the southern hemisphere (8). August is the coldest month (average temperature of 11°C) on Amsterdam Island, and the majority of cows died during the winter in the last trimester of pregnancy (8).

The best controlled research on starvation in large mammals is on voluntary starvation in humans; as a method of weight loss, hunger strikes in incarcerated political prisoners, and in the psychiatric condition anorexia nervosa. Obese humans practicing temporary complete anorexia can be expected to lose 1.75 kg/wk although total body potassium loss is a frequent occurrence and cardiac complications may occur (9,10). Early records of hunger strikes in the 1920’s suggest that with the provision of water, previously healthy resolute political prisoners could be expected to live 9 to 13 wk (11). The time to death was not significantly extended in the 1981 Bobby Sands/Maze Prison hunger strike, in which 10 previously healthy males aged 27 ± 24 y survived 62.0 ± 7.4 d after complete food refusal (12). If hunger strikers will accept salted and sugared liquids and vitamin B complex supplementation, especially thiamin, they can greatly extend the normal survival time of 60 d to 165 to 180 d (13). In human starvation, as in other mammals, risk of death occurs when about 40% of the original body mass has been lost (14). A single controlled starvation and re-feeding study on 36 human volunteers, the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, resulted in the 2-volume monograph The Biology of Human Starvation, in 1950 (15). Individuals in this study lost 25 to 30 lb, similar to civilian survivors of NAZI occupied Holland (16). This level of weight loss in humans is probably only about 50% of lethal starvation challenge (loss of 40% body mass).

Hypothermia

The treatment of deep accidental hypothermia in humans (core temperature < 28°C), a condition characterized by neurological depression and circulatory failure, is well-documented in human emergency medicine (17). In humans cooled for cardiac surgery, ventricular fibrillation generally occurs at 22°C and asystole at 20°C (18). Accidental human hypothermia is a less controlled setting with patients presenting with a variety of abnormal cardiac rhythms (18,19). Combined starvation and cold stress has been studied in humans at the population level in relation to war (20) and the excess mortality in the poor or partially homeless during winter (21–23).

Cattle respond to cold stress and a decreased plane of nutrition by lowering their metabolic requirements and altering behavior (24). Overwinter basal metabolic requirements per kg of calf weight vary by genetic type of beef cattle (25). A further possible thermal stress in cattle in Manitoba is the widespread practice of not providing ice-free water over the winter period since cattle on a good nutritional plane can rapidly ingest snow without apparent ill effects. Cattle on a high plane of nutrition can tolerate the thermal stress of rapid ingestion of snow, drawing approximately equally from body heat by increased metabolic heat production and latent heat of digestion to melt snow or ice and bring the water up to body temperature (26). Latent heat of digestion may be minimal in nutritionally stressed cattle.

Field inspection

Starvation as a cause of death should be suspected when a herd of cattle is identified in late winter or early spring, with i) a significant number of dead cattle of all ages, ii) carcass emaciation, and iii) surviving cattle are thin. For Manitoba, we estimate the expected mature cow over-winter death rate to be 1 cow in 200 entering the winter feeding period. This estimate is in reasonable agreement with data from the United States where the percentage of weaned or older beef breeding cattle that died or were lost from all causes during the first 6 mo of 2008 was about 1% and similar across herd size and region, and where a regional maximum of 0.8% of beef herds lost more than 10% of weaned or older beef breeding cattle (all causes) during the first 6 months of 2008. These data include cows lost during spring calving (23.7%), and 25.1% of breeding cows that die of unknown causes (27). Reliable data are not collected on beef cattle death loss in Manitoba; however, as a result of average management attention, beef cows that become unproductive are culled long before they would die of natural causes.

Carcasses of cattle dead of starvation present the following characteristics: i) they have very poor or no fat covering the bony prominence [compatible with 2 on the Wagner Scale for live animals (Table 2), to score 1 on the Wagner scale — the animal has to also demonstrate physical weakness]; ii) not bloated at postmortem; and iii) many are not significantly scavenged. Carcasses are generally frozen solid and often frozen to the underlying substrate or to each other, which is a problem for carcass removal for postmortem examination. Stacking of dead carcasses is usually observed. Clusters of starvation deaths (10% to 55% of the herd) have only been seen in late winter and early spring in Manitoba.

Occasionally a live cow is identified in BCS 1: severely emaciated, all ribs and bone structure easily visible and physically weak, and has difficulty standing or walking, with no external fat present by sight or touch. These individuals may be recumbent and unable to rise at the time of initial inspection or they become recumbent during the process of attempting to load the animals when they are seized. These animals are bright and alert and repeatedly attempt to stand but are unable to rise (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Image of a cow in Body Condition Score 1 (Ref. 2) as she meets the emaciation criteria of BCS 2 with the addition of weakness which prevents her from standing up. a) Cow is bright and alert (rectal temperature was not taken). Image was captured January 24, 2003 at 11:51 AM. b) In this image you can visualize the spine of the right scapula. This cow died at about 15:30 the same day. There was no manure build up behind this cow. Average hourly environmental temperature for the previous 10 days was −20.6 ± 5.5°C (Max −7.1, Min −32.2°C); Wind chill average −29.5°C − 5.7°C (Max −14°C, Min −43°C) [Environment Canada, Gimli MB weather station (1)].

Where whole carcasses cannot be recovered for postmortem examination because of logistics of deep snow, frozen together, or lack of mechanical assistance, removal of a femur for postmortem evaluation can often be accomplished. When cutting into the thigh muscle of the carcass no subcutaneous fat is visible but the muscle tissue is bright pink and well-preserved (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

a) Image of a cow in Body Condition Score 2 (presumably 1, as probably weak prior to death); b) field evidence collection, image of thigh muscle reflected and middle of femur exposed, muscle tissue is bright pink and significant muscle tissue remains; c) image of split femur bone showing serous atrophy of fat (photo Mark Swendrowski).

In starved cattle where the carcass is found in place it is unusual to find a significant volume of manure behind the animal, indicating that the time between involuntary recumbency and death is insufficient to allow for rectal or large intestinal emptying. Rarely have we identified evidence suggestive of large intestinal emptying between the time of involuntary recumbency and death from starvation-hypothermia (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Field photographs of carcasses of a presumed cow calf pair. a) pair as found in situ in a wooded area April, 2008 (photos courtesy C. Marion), there is no fecal build-up behind the calf carcass (foreground) suggestive of recumbency quickly followed by death. b) same pair of carcasses, image captured from about 4 meters away. There is significant evidence of intestinal emptying of the cow, suggesting she initially became recumbent in the lower edge of the photo and over several days crawled into position to die in contact with the carcass of her calf.

In the review of herd management of cases of winter starvation thus far investigated by veterinarians in Manitoba (Table 1 and additional cases failing to meet the inclusion criteria), there has been a consistent failure of the farm manager to segregate animals by gender and age and feed according to nutritional requirements of each class of animal. In addition, there are usually no handling facilities, no seasonal breeding program (bulls are never segregated), and limited or no relationship with a veterinary practice.

Postmortem evaluation

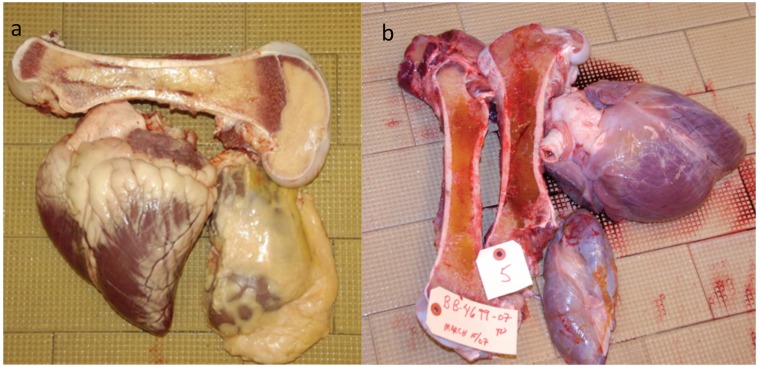

In mass cattle mortalities related to late winter starvation, whole non-scavenged carcasses are often available for postmortem examination. In the investigations referenced in Table 1 at least 3 carcasses were presented for complete postmortem examination by a trained veterinary pathologist, to rule out other possible causes of death. In the absence of postmortem evidence of other pathological or disease states, these cases universally were marked by serous atrophy of the fat found at the heart base, peri-renal area, and in the femur marrow (Figure 4). Bone marrow fat typically is the last reserve of fat depleted in cases of starvation (28).

Figure 4.

a) Gross postmortem of excised normal heart, kidney, and split femur from a feedlot heifer which had died of blackleg (photos, courtesy M. Swendrowski). b) similar image of a heart, kidney, and split femur from a similar aged animal which had died of starvation.

Gelatinous transformation of the bone marrow (GTM) has been recognized by pathologists for decades under different terms. It is a morphologic change resulting from atrophy of the fat cells, loss of hematopoietic cells, and the deposition of gelatinous substance in the marrow space (29). Hyaluronic acid is a major component of the gelatinous material. The final stages of anorexia nervosa are accompanied by GTM and this is a reversible condition highly correlated with the amount of weight loss (30). In evaluating cause of death and body condition in wildlife, bone marrow fat content has also been used (31,32). Bovine bone marrow fat does not significantly deteriorate for 30 to 60 d whether kept frozen or at room temperature (33).

In the postmortem examination of farm animals, the residual fat in bone marrow can be accurately quantified using solvent extraction with normal large animals having more than 80% fat and animals suspected of death by starvation of having < 20% (33). However, we have found similar evidence using a simple air dry technique. The femur is bone of choice to evaluate residual energy reserves based on ease of access, volume of bone marrow and size of medullary cavity. The humerus can also be used. The gross appearance of the bone marrow is evaluated and recorded using a descriptive scale of gelatinous, slightly greasy, soft and thick greasy, firm and waxy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Air dried bone marrow percent fat analysis, selected post mortem cases

| Bone marrow | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Species | Age* | Bone marrow appearance | wet weight (g) | dry weight (g) | % fat |

| Alpaca | M | White, firm, greasy | 23.30 | 18.80 | 80.70 |

| Bovine | M | White firm, greasy | 25.60 | 20.70 | 80.90 |

| Bovine | M | White, firm, greasy | 38.40 | 35.00 | 91.10 |

| Elk | M | White, firm, greasy | 15.80 | 12.20 | 77.20 |

| Goat | M | White, firm, greasy | 9.70 | 8.20 | 84.50 |

| Moose | M | White, firm, greasy | 31.90 | 24.70 | 77.00 |

| Moose | M | White, firm, greasy | 40.00 | 31.30 | 78.25 |

| Pig | M | White, firm, greasy | 11.60 | 10.40 | 89.60 |

| Sheep | < 1 y | White, firm, greasy | 14.10 | 11.50 | 82.00 |

| Sheep | < 1 y | White, firm, greasy | 6.40 | 5.50 | 86.00 |

| White-tailed deer | M | White, firm, greasy | 41.90 | 31.60 | 75.00 |

| Alpaca | M | Red, gelatinous | 21.50 | 1.8 | 8.37 |

| Alpaca | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 21.90 | 6.6 | 30.50 |

| Alpaca | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 26.10 | 1.5 | 5.70 |

| Antelope | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 22.50 | 2.10 | 9.30 |

| Bovine | Calf | Red, gelatinous | 25.50 | 3.20 | 12.55 |

| Bovine | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 30.00 | 2.40 | 8.00 |

| Bovine | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 74.90 | 5.40 | 7.20 |

| Bovine | M | Yellow, slightly greasy | 33.90 | 11.90 | 35.00 |

| Bovine | Calf | Dark red, gelatinous | 6.30 | 0.70 | 11.10 |

| Bison | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 89.70 | 10.80 | 12.00 |

| Bison | M | Yellow, slightly greasy | 69.50 | 27.50 | 39.50 |

| Bison | M | White, soft & thick greasy | 49.80 | 26.80 | 53.80 |

| Dog | M | Red, gelatinous | 8.90 | 2.30 | 25.80 |

| Dog | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 17.60 | 1.50 | 8.52 |

| Horse | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 44.90 | 6.70 | 14.92 |

| Horse | M | Red, gelatinous | 33.10 | 4.00 | 12.10 |

| Elk | Calf | Yellow, gelatinous | 9.00 | 2.70 | 30.00 |

| Elk | M | Yellow, gelatinous | 39.80 | 5.10 | 12.80 |

| Goat | M | Red, gelatinous | 7.70 | 0.80 | 10.40 |

| Pig | M | Red, slightly greasy | 4.40 | 2.00 | 45.00 |

| Sheep | M | Yellow, gelatinous, Johne’s | 14.80 | 3.10 | 21.00 |

| Sheep | < 1 y | Yellow, gelatinous | 10.20 | 0.90 | 8.82 |

M — indicates a mature or adult specimen.

A bone marrow sample is removed from the medullary cavity of the bone using a scoop, being careful to collect only bone marrow not medullary bone. Ideally, 30 g of bone marrow or more is collected, but in smaller young animals this is challenging due to small sample volume. We have also used both femur bones to obtain a heavier sample. The sample is collected into a weighed round 9.0 cm diameter plastic petri dish which is weighed on an electronic scale to determine the bone marrow “wet weight.” The case number, species, plate weight, and “wet weight” are recorded on the petri plate with black indelible ink. The open petri plate is placed under a running fume hood to air dry. The weight of the plate and bone marrow are recorded daily, using the same electronic scale, until the weight remains stable for 72 h. The weight of the plate is subtracted from this final bone marrow + plate weight to get the “dry weight.” The proportion of the original sample remaining after the water fraction evaporates is the lipid fraction. A percentage bone marrow fat is then calculated using the difference between the wet and dry weights (i.e., dry weight/wet weight × 100 = percent fat). In our experience control animals have bone marrow fat percentages ranging from 70% to 80%. Animals with emaciation and serous atrophy can have bone marrow fat values of < 10% using this crude technique.

An experienced pathologist organoleptic evaluation of serous atrophy of bone marrow is strongly supported by data from air drying of bone marrow in all vertebrates thus far examined. This supports an interpretation of significant depletion of whole body energy reserves when serous atrophy of bone marrow is found on gross examination of split femur. Laboratory evaluation of bone marrow fat percentage may add little value to the gross pathologic diagnosis.

Discussion

Veterinarians and diagnostic laboratories are frequently required to assess the antemortem body condition of cattle which have died under suspicious circumstances. We have returned 2 to 3 mo after seizing herds in nutritional distress to retrieve femurs from dead piles as the snow thaws and carcasses thaw out. Femurs collected in the early spring from dead piles are well-preserved if vertebrate scavenging has not exposed the surface of the femur which will result in water loss from the marrow space. Carcass destruction is primarily from insect proliferation after the ambient temperature is consistent with fly maggot survival.

It appears from our clinical experience and postmortem evaluation of beef cattle that late winter mass mortality in Manitoba is primarily due to calorie malnutrition combined with slow or more frequently rapid progressive hypothermia. This is consistent with the literature that hypothermia encourages recumbency as the recumbent position conserves about 10% of caloric metabolic requirements (25). It is unusual for veterinary forensic investigators to observe accumulation of feces behind emaciated carcasses in Manitoba and individual recumbent animals have been observed to die within a few hours. Therefore, based on observation and postmortem evaluation the normal pathogenesis of starvation related death in late winter is as follows: i) weak animals in BCS 1 become recumbent to conserve metabolic resources; ii) once recumbent the core body temperature starts to drop decreasing the efficiency of skeletal muscle making it difficult to regain the standing position; iii) rumen microflora die en masse as core body temperature decreases preventing postmortem bloat; iv) when core body temperature reaches about 22°C the heart becomes asystolic and the animal dies. The carcass then goes on to freeze and is preserved in excellent condition until spring thaw, barring predation.

Carcasses of winter starvation cattle in Manitoba appear to have significantly more residual muscle mass than similar cattle dying of drought-induced starvation in more temperate areas such as Texas and Australia. It appears that starvation-stressed cattle in Manitoba cannot metabolize protein rapidly enough to prevent death by hypothermia.

In many cases of multiple cattle death loss due to starvation, the cattle appear to have died over a fairly short temporal window. This is similar to the Maze prison hunger strike in which deaths clustered fairly tightly around 62 d of starvation. Widespread scavenging is usually not common in cattle winter mass mortality, probably because the massive number of mortalities overwhelms the local population of potential mammalian and avian scavengers. Also, when weak cows calve, dead or weak newborn calves are an easier and preferred food source than frozen emaciated cows.

Producers generally deny that cattle have died from starvation as that would indicate culpability on their part. However, producers are willing do attribute winter mortality to severe weather (hypothermia). A late-season blizzard in Manitoba and Saskatchewan on April 29 and 30, 2011 resulted in a special livestock mortality compensation program in Manitoba (Manitoba Spring Blizzard Mortalities Assistance, 2011). That program resulted in claims that paid out $6 591 000 (34).

Practitioners should become competent in identifying or suspecting winter starvation, and develop relationships with veterinary pathologists to confirm this diagnosis, especially as part of professional responsibility in provinces where veterinarians are obliged by legislation to report animal neglect. Veterinarians competent in diagnosing starvation and producer groups and governments aware of that competence could minimize the moral hazard in ad hoc disaster assistance programs related to severe weather. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.National Climate Data and Information Archive. Environment Canada. [Last accessed August 14, 2012]. Available from: http://climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca/climateData/canada_e.html.

- 2.Wagner JJ, Lusby KS, Oltjen JW, Rakestraw J, Wettemann RP, Walters LE. Carcass composition in mature Hereford cows: Estimation and effect on daily metabolizable energy requirement during winter. J Anim Sci. 1988;66:603–612. doi: 10.2527/jas1988.663603x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baur LS, Filer LJ. Influence of body composition of weanling pigs on survival under stress. J Nutrition. 1959;69:128–134. doi: 10.1093/jn/69.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavassoli M, Eastlund DT, Yam LT, Neiman RS, Finkel H. Gelatinous transformation of bone marrow in prolonged self-induced starvation. Scand J Haematol. 1976;16:311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1976.tb01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witham CL, Stull CL. Metabolic responses of chronically starved horses to refeeding with three isoenergetic diets. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;212:691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiting TL, Salmon RH, Wruck GC. Chronically starved horses: Predicting survival, economic and ethical considerations. Can Vet J. 2005;46:320–324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josefsen TD, Sorensen KK, Mork T, Mathiesen SD, Ryeng KA. Fatal inanition in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus): Pathological findings in completely emaciated carcasses. Acta Vet Scand. 2007;49:27–37. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-49-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berteaux D. Female-based mortality in a sexually dimorphic ungulate: Feral cattle of Amsterdam Island. J Mamm. 1993;74:732–737. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson TJ, Runcie J, Miller V. Total fasting for up to 249 days. The Lancet. 1966;288:992–996. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92925-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose M, Greene RM. Cardiovascular complications during prolonged starvation. West J Med. 1979;130:170–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggs M. Sociology Working Papers, Paper # 2007-03. University of Oxford; [Last accessed August 14, 2012]. The Rationality of Self-inflicted Suffering: Hunger Strikes by Irish Republicans, 1916–1923. Available from: http://users.ox.ac.uk/~sfos0060/SWP2007-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melaugh M. The hunger strike of 1981 — A chronology of main events. [Last accessed August 14, 2012]. Available from: http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/hstrike/chronology.htm.

- 13.Altun G, Akansu B, Altun BU, Azmak D, Yilmaz A. Deaths due to hunger strike: Post-mortem findings. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;146:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight B. Forensic Pathology. London, UK: Edward Arnold; 1991. Neglect, starvation, and hypothermia; pp. 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Michelsen O, Taylor LH. The biology of human starvation. 1–2. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 16.French CE, Stare FJ. Nutritional surveys in western Holland: Rotterdam, 1945. J Nutr. 1947;33:649–660. doi: 10.1093/jn/33.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brát R, Skorpil J, Bárta J, Suk M, Schichel T. Rewarming from severe accidental hypothermia with circulatory arrest. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2004;148:51–53. doi: 10.5507/bp.2004.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southwick FS, Dalglish PH., Jr Recovery after prolonged asystolic cardiac arrest in profound hypothermia. A case report and literature review. J Am Med Assoc. 1980;243:1250–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JH, Lee JE, Kim BK, Lee KM, Kim JS, Han SB. Hypothermic cardiac arrest. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:765–767. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sparén P, Vågerö D, Shestov DB, et al. Long term mortality after severe starvation during the siege of Leningrad: Prospective cohort study. Brit Med J. 2004;328:11–15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37942.603970.9A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alyin P, Morris S, Wakefield J, Grossinho A, Jarup L, Elliot P. Temperature, housing, depravation and their relationship to excess winter mortality in Great Britain, 1986–1996. Int J Epidemol. 2001;30:1100–1108. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carder M, McNamee R, Beverland I, Cohen GR, Boyd J, Agius RM. The lagged effect of cold temperature and wind chill on cardiorespiratory mortality in Scotland. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:702–710. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.016394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donaldson GC, Tchernjvskii VE, Ermakov SP, Bucher K, Keatinge RW. Winter mortality and cold stress in Yekaterinburg, Russia: Interview survey. Brit Med J. 1998;316:514–518. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7130.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keren NR, Olson BE. Thermal balance of cattle grazing winter range: Model application. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:1238–1247. doi: 10.2527/2006.8451238x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis KC, Tess MW, Kress DD, Doornbos DE, Anderson DC. Life cycle evaluation of five biological types of beef cattle in a cow-calf range production system: II. Biological and economic performance. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:2591–2598. doi: 10.2527/1994.72102591x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degen AA, Young BA. Effects of ingestion of warm, cold and frozen water on heat balance in cattle. Can J Anim Sci. 1984;64:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.USDA Beef 2007–08 Part V: Reference of Beef Cow-calf Management Practices in the United States, 2007–08. [Last accessed August 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/beefcowcalf/downloads/beef0708/Beef0708_dr_PartV.pdf.

- 28.Böhm J. Gelatinous transformation of the bone marrow. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:56–65. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sicard D, Casadevall N, Wyplisz B, Picart F, Blanche P. Anorexia nervosa and gelatinous transformation of bone marrow. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1994;36:S85–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abell E, Feliu E, Granda I, et al. Bone marrow changes in anorexia nervosa are correlated with the amount of weight loss and not with other clinical findings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:582–588. doi: 10.1309/2Y7X-YDXK-006B-XLT2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neiland KA. Weight of dried marrow as an indicator of fat in caribou femurs. J Wildlife Manag. 1970;34:904–907. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguirre AA, Bröjer C, Mörner T. Descriptive epidemiology of roe deer mortality in Sweden. J Wildl Dis. 1999;34:753–762. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-35.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamoureux JL, Fitzgerald SD, Church MK, Agnew DW. The effect of environmental storage conditions on bone marrow fat determination in three species. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:312–315. doi: 10.1177/104063871102300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistics Canada. Direct payments to agriculture producers — May 2012, Table 1-31, Direct payments to agriculture producers — Agriculture economic statistics. 2011. [Last accessed August 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/21-015-x/21-015-x2012001-eng.pdf.