Abstract

A 10-year-old spayed female dalmatian dog developed acute vomiting and abdominal pain. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen showed right hydronephrosis and proximal ureter dilation with mild retroperitoneal free fluid. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen confirmed the ultrasonographic findings and revealed, additionally, a right ureteral stone. Spontaneus rupture of the right ureter was confirmed with CT post ultrasound-guided percutaneous antegrade pyelography. Pyeloureteral rupture and the presence of a ureteral stone were confirmed at surgery.

Résumé

Pyélographie antégrade percutanée guidée par échographie avec tomodensitométrie pour le diagnostic d’une rupture urétrale partielle spontanée chez un chien. Une chienne Dalmatien stérilisée âgée de 10 ans a manifesté des vomissements et de la douleur abdominale aigus. Une échographie de l’abdomen a montré de l’hydronéphrose à droite et une dilatation proximale de l’urètre avec un peu de liquide rétropéritonéal libre. Une tomodensitométrie de l’abdomen a confirmé les résultats de l’échographie et a révélé, en plus, un calcul urétéral droit. Une rupture spontanée de l’urètre droit a été confirmée par tomodensitométrie après une pyélographie antégrade percutanée guidée par échographie. La rupture pyélo-urétérale et la présence de calcul urétéral ont été confirmées à la chirurgie.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Case description

A 10-year-old spayed female dalmatian dog developed acute vomiting and anorexia. At physical examination the dog had right cranial abdominal pain; no other abnormalities were detected.

After supportive treatment, including pain-medication and IV fluids, an abdominal radiographic study and an abdominal ultrasound (MyLab 30 Gold; Esaote, Milano, Italy) were performed. Radiographs showed an increased ill-defined retroperitoneal opacity. The abdomen was otherwise unremarkable. At ultrasound examination, right renal hydronephrosis with loss of cortical-medullary distinction and proximal hydroureter (0.78 cm maximal diameter) were documented. A small amount of retroperitoneal effusion was detected surrounding the right kidney and ultrasound-guided paracentesis of the fluid was performed. The left kidney had irregular margins but with normal echogenicity, and the urinary bladder was within normal limits. At careful examination of the trigonal area, a “ureteral jet” was visible only on the left side. Biochemical analysis of the sample revealed an increased creatinine concentration (716 μmol/L), compared with serum creatinine, which was 124 μmol/L, indicating free urine. Analysis of urine from the bladder showed the presence of urate crystals. Based on these findings, spontaneous ureteral rupture was suspected.

In order to identify the site of rupture and to confirm the underlying cause, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed. Images were obtained with a 4-slices helical CT scanner (Light Speed; GE Medical Systems, Bergamo, Italy). The dog was positioned in dorsal recumbency and pre- and post-contrast abdominal images were acquired using a pitch of 1.5, a speed acquisition of 7.5 mm/s, with 120 Kv and 220 mA. A small amount of free retroperitoneal fluid on the right, right hydronephrosis, and dilation of the proximal right ureter were confirmed. Free fluid in the left retroperitoneal space was also visible, but to a lesser degree. A hyperattenuating well-defined calculus 1.2 cm in diameter was located in the right proximal ureteral tract (Figure 1).

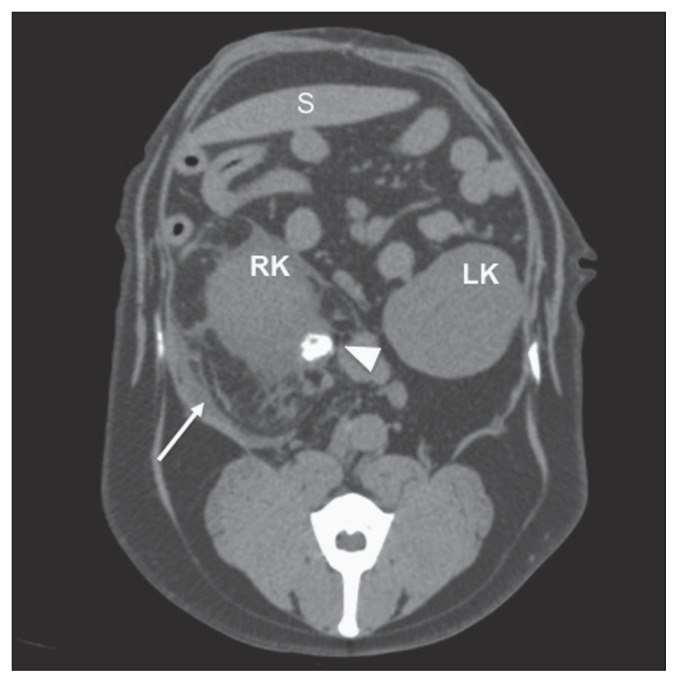

Figure 1.

Transverse computed tomographic image of the mid abdomen. A 1.2 cm hyperattenuating (581 HU) calculus is visible at the level of the proximal ureter (arrowhead). Note the presence of free fluid in the retroperitoneal space, which appears as curvilinear hyperattenuating bands of variables thickness in the retroperitoneal fat (arrow). RK — right kidney, LK — left kidney, S — spleen.

Computed tomographic intravenous pyelography (IVP) was performed by injecting iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque 350 mg/mL; Ioexolo, Titolare AIC, GE Healthcare S.r.l., Milano, Italia) at a total dose of 60 mL through an 18-gauge catheter positioned in the left cephalic vein, using a power injector (Medrad; Medrad Italia, Cava Manara, Italy). Images were acquired immediately, and at 10 and 15 min post- injection. An increased attenuation of the free retroperitoneal fluid (18 HU pre-contrast and 101 HU post-contrast) was observed (Figure 2). Of note, at time 10 min, a small amount of contrast medium was detected within the right ureter, just caudal to the calculus, but leakage of contrast medium outside the ureter was not observed. To help determine the presence and site of urine leakage, additional CT scans were performed after an ultrasound-guided percutaneous antegrade pyelography. A 22-gauge spinal needle was introduced into the right renal pelvis through the renal cortex under ultra-sonographic guidance. Thereafter, 5 mL of urine were removed and 4 mL of iodinated contrast medium (350 mg/dL) were injected manually. The CT scan was repeated using the same technique from the cranial pole of the right kidney to the mid-portion of the ureter. These images revealed leakage of contrast medium at the cranio-dorsal and lateral aspect of the proximal ureter (Figures 3, 4). The presence of the right ureteral calculus and ureteral rupture at the pyeloureteral junction were confirmed at surgery. Nephrectomy was elected due to the marked degenerative macroscopic changes detected in the right kidney.

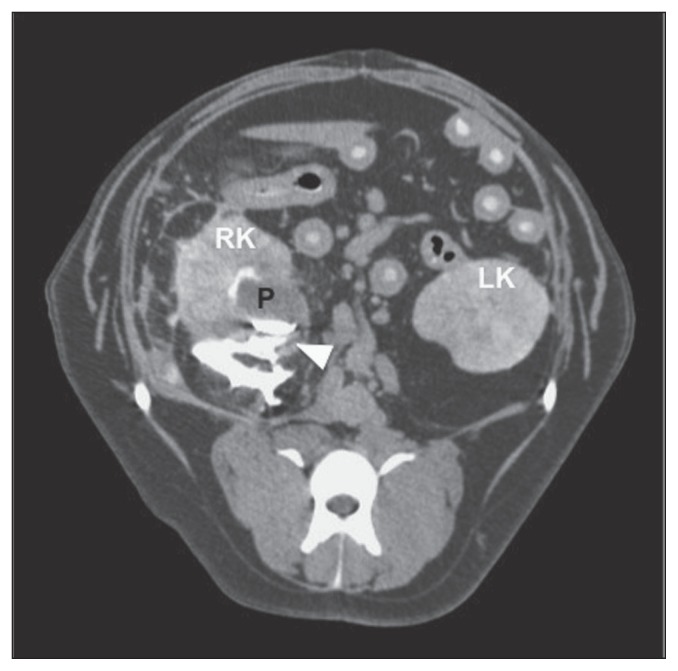

Figure 2.

Transverse computed tomographic image after intravenous pyelography (15 min delayed acquisition). Note the irregular margins of the right kidney and the heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the right kidney affected by hydronephrosis. RK — right kidney, P — renal pelvis, S — spleen.

Figure 3.

Transverse computed tomographic image after percutaneous ultrasound-guided antegrade pyelography. Note the leakage of contrast medium in the retroperitoneal space (arrowhead). RK — right kidney, LK — left kidney, P — renal pelvis.

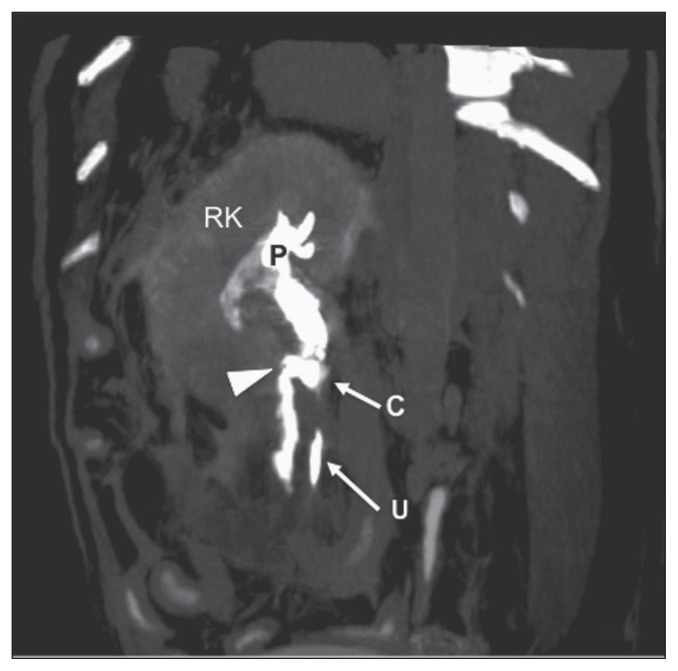

Figure 4.

Dorsal multiplanar reconstruction image after percutaneous ultrasound-guided antegrade pyelography. Contrast medium is visible inside the right ureter distal to the stone, confirming that the obstruction was not complete. Note the point of leakage at the level of the junction between the renal pelvis and the ureter (arrowhead). RK — right kidney, U — ureter, C — calculus, P — renal pelvis.

Discussion

The term urinoma is used to define an accumulation of free urine, often becoming encapsulated with time, that may be initially occult (1) but that can lead to complications such as abscess formation and electrolyte imbalance if not promptly diagnosed. Urinomas are typically caused by ureteral rupture. Injury to the ureter is most commonly traumatic, but can also be iatrogenic or secondary to obstruction from calculi, neoplasia, or stricture subsequent to increased intrapelvic pressure (2–4). Diagnostic imaging plays a key role in identifying urine leaks and determining their cause and extent. In human patients with renal colic, abdominal radiographs centered on the urinary system are initially obtained (Kidney-Ureter-Bladder radiography, KUB) (5–7). In both humans and dogs, however, certain uroliths such as urate and cystine calculi are not visible on survey radiographs, limiting the diagnostic sensitivity of that method (5–8). In our case, the ureteral stone was not visible on survey radiographs. Dalmatian dogs are predisposed to the development of urate urolithiasis. In this breed there is reduced purine metabolism because of a defective hepatic cell membrane transport system for uric acid (9,10). Although no analysis of the stone was conducted, the urine analysis showed the presence of urate crystals. In humans it is reported that attenuation of the stone by CT and its proximal or distal ureteral localization are predictable for detection of the urolith with KUB. On the other hand, the size of the stone is not a significant predictor for its detection with survey radiographs (11,12).

The dog herein was presented to our clinic for acute abdominal pain. Ultrasound plays an important role in the investigation of acute abdomen in both humans and dogs (13,14), although its reliability, especially when looking for ureteral calculi, is low (10% to 50%) (15). In dogs, the most common ultra-sonographic findings with ureteral obstruction and rupture are pyelectasia, hydronephrosis, proximal hydroureter, absence of “ureteral jet” in the trigone of the urinary bladder, and retroperitoneal fluid accumulation (3,4,16). The identification of small uroliths can be difficult especially in obese dogs, due to the superimposition of gastrointestinal structures such as the descending colon, or in dogs with lack of substantial ureteral distension (16). The combined use of ultrasound and radiology is often preferred when looking for ureteral obstruction (17).

The presence of retroperitoneal fluid in this dog could have been a consequence of acute renal failure (18). Fine-needle aspiration of the fluid and evaluation of the ratio between retroperitoneal fluid and serum creatinine concentrations (19) were required to diagnose a uroretroperitoneum. Once uroretroperitoneum is confirmed, a contrast procedure should be performed in order to find the point of leakage.

In veterinary medicine, several reports describe the use of ultrasound to guide antegrade pyelography to help detect ureteral obstruction in dogs and cats (17,20–23). However, the feasibility and utility of antegrade pylography using CT has not yet been reported.

In humans, CT represents the method of choice to diagnose ureteral leaks (24) and intravenous pyelography and antegrade and retrograde pyelography have complementary roles when ureteral rupture is suspected. Unenhanced CT is the most accurate imaging modality for the diagnosis of ureteral stones, with an accuracy that is superior to those of plain KUB radiographs and excretory urography (25).

The use of CT-IVP in humans with delayed imaging is the least invasive and most readily available technique, but it is not recommended in patients with elevated creatinine levels or those allergic to contrast media. In the dog in this report, because serum creatinine concentration was normal, a CT-IVP with acquisition of corticomedullary and delayed imaging phases was performed without any definitive information regarding the site of urine leakage. Ureteral obstruction causes an increase in ureteral pressure that is transmitted to nephrons that consequently release vasoactive mediators, which decrease the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (17). For this reason, IVP is not always useful in these patients and did not provide any additional information regarding the site of urine leakage in our dog. The reported sensitivity of IVP technique to detect urine leakage in humans is indeed low (i.e., 33%), justifying the use of antegrade and retrograde pyelography to confirm ureteral injuries (26).

In the present case, a small amount of free retroperitoneal fluid was also noted in the left retroperitoneal space, which may have been due to the transit of free urine from the right side. In humans, it has been shown that in cases of urine leakage the fluid may cross the midline within the perirenal space anterior to the aorta and inferior vena cava and extend into the contralateral perirenal space (27). We presume this also happened in our patient.

Percutaneous antegrade pyelography allows the clinician to evaluate the renal pelvis and ureter, to localize the ureteral obstruction, and to determine whether the obstruction is partial or complete (17). Percutaneous renal puncture may be performed rapidly using ultrasound guidance and constitutes both diagnostic and therapeutic goals in humans (28). Potential complications include hematuria, temporary obstruction due to clots, subcapsular or perinephric hemorrhage, infection, local pain, and perforation of adjacent non-renal structures. Despite the hematuria, the incidence of significant complications which require treatment or hospitalization is reported to be less than 1% in humans (29). There was no evidence of complications after the percutaneous renal puncture in the dog in this case.

In our patient, the ureteral stone was not visible in survey radiographs and at ultrasound examination, whereas it was easily detected with unenhanced CT. It is therefore possible that in dogs, as in humans, CT offers a diagnostic advantage over radiographs and ultrasonography in the search for ureteroliths.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first case report describing the use of ultrasound-guided percutaneous antegrade pyelography imaged with CT for a case of spontaneous ureteral rupture. This procedure may be beneficial in dogs with non-traumatic rupture of the ureter in order to assess the underlying process, locate the point of leakage, and prescribing optimal treatment. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, et al. Urinomas caused by ureteral injuries: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:88–92. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanika C, Rebar AH. Ureteral transitional cell carcinoma in the dog. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:643–646. doi: 10.1177/030098588001700517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyles AE, Douglas JP, Rottman JB. Pyelonephritis following inadvertent excision of the ureter during ovariohysterectomy in a bitch. Vet Rec. 1996;139:471. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.19.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisse C, Aronson LR, Drobatz KJ. Traumatic rupture of the ureter: 10 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2002;38:188–194. doi: 10.5326/0380188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackman SV, Potter SR, Regan F, Jarrett TW. Plain abdominal x-ray versus computerized tomography screening: Sensitivity for stone localization after nonenhanced spiral computerized tomography. J Urol. 2000;164:308–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu G, Rosenfield AT, Anderson K, Scout L, Smith RC. Sensitivity and value of digital CT scout radiography for detecting ureteral stones in patients with ureterolithiasis diagnosed on unenhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:417–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.2.10430147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ege G, Akman H, Kuzucu K, Yildiz S. Can computed tomography scout radiography replace plain film in the evaluation of patients with acute urinary tract colic? Acta Radiol. 2004;45:469–73. doi: 10.1080/02841850410005264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park RD, Wrigley RH. The urinary bladder. In: Thrall DE, editor. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 5th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 708–724. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giesecke D, Tiemeyer W. Defect of uric acid uptake in Dalmatian dog liver. Experientia. 1984;40:1415–1416. doi: 10.1007/BF01951919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bannasch DL, Ling GV, Bea J, Famula TR. Inheritance of urinary calculi in the Dalmatian. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:483–487. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<483:ioucit>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung S, II, Kim YJ, Park HS, et al. Sensitivity of digital abdominal radiography for the detection of ureter stones by stone size and location. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:879–882. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181ec7e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang CC, Chuang CK, Wong C, Wang LJ, Wu CH. Useful prediction of ureteral calculi visibility on abdominal radiographs based on calculi characteristics on unenhanced helical CT and CT scout radiographs. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:184. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gokçe AH, Aren A, Gokçe FS, Dursun N, Barut AY. Reliability of ultrasonography for diagnosing acute appendicitis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17:19–22. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2011.82195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter PC. Approach to the acute abdomen. Clin Tech Small An P. 2000;15:63–69. doi: 10.1053/svms.2000.6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalla Palma L, Pozzi-Mucelli R, Stacul F. Present-day imaging of patients with renal colic. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:4–17. doi: 10.1007/s003300000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penninck D. In: Atlas of Small Animal Ultrasonography. Penninck D, d’Anjou MA, editors. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell publishing; 2008. pp. 281–318. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berent AC. Ureteral obstructions in dogs and cats: A review of traditional and new interventional diagnostic and therapeutic options. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2011;21:86–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2011.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holloway A, O’Brien R. Perirenal effusion in dogs and cats with acute renal failure. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2007;48:574–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2007.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chad S, Karen MT, Otto CM. Evaluation of abdominal fluid: Peripheral blood creatinine and potassium ratios for diagnosis of uroperitoneum in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2001;11:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivers BJ, Walter PA, Polzin DJ. Ultrasonographic-guided, percutaneous antegrade pyelography: Technique and clinical application in the dog and cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1997;33:61–68. doi: 10.5326/15473317-33-1-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adin CA, Herrgesell EJ, Nyland TG, et al. Antegrade pyelography for suspected ureteral obstruction in cats: 11 cases (1995–2001) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222:1576–1581. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackerman N, Ling GV, Ruby AL. Percutaneous nephropyelocentesis and antegrade urography: A fluoroscopically assisted diagnostic technique in canine urology. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1980;21:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaney FA, Dennison S. Sonography-guided pyelocentesis and pyelography in cats: The sonographer’s role. J Diag Med Sonog. 2010;26:116–120. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Titton RS, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Harisinghani MG, Arellano RS, Mueller PR. Urine leaks and urinomas: Diagnosis and imaging-guided intervention. Radiographics. 2003;23:1133–1147. doi: 10.1148/rg.235035029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi T, Nishizawa K, Watanabe J, Ogura K. Clinical characterstics of ureteral calculi detected by nonenhanced computerized tomography after unclear results of plain radiography and ultrasonography. J Urol. 2003;170:799–802. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000081424.44254.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghali AM, El Malik EM, Ibrahim AI, Ismail G, Rashid M. Ureteric injuries: Diagnosis, management and outcome. J Trauma. 1999;46:150–158. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199901000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang EK, Glorioso L. Management of urinomas by percutaneous drainage procedures. Radiol Clin North Am. 1986;24:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfister RC, Newhouse JH. Interventional percutaneous pyeloureteral techniques II. Antegrade pyelography and ureteral perfusion. Radiol Clin North Am. 1979;17:341–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfister RC, Newhouse JH, Yoder, et al. Complications of pediatric percutaneous renal procedures: Incidence and observations. Urol Clin North Am. 1983;10:563–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]