Abstract

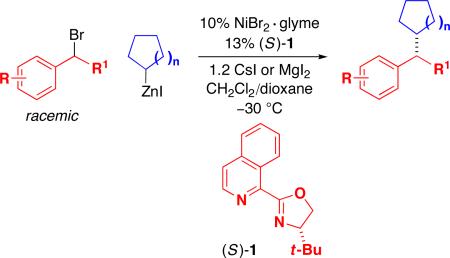

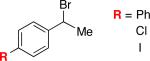

We have developed a nickel-catalyzed method for the asymmetric cross-coupling of secondary electrophiles with secondary nucleophiles, specifically, stereoconvergent Negishi reactions of racemic benzylic bromides with achiral cycloalkylzinc reagents. In contrast to most previous studies of enantioselective Negishi cross-couplings, tridentate pybox ligands are ineffective in this process; however, a new, readily available bidentate isoquinoline-oxazoline ligand furnishes excellent ee's and good yields. The use of acyclic alkylzinc reagents as coupling partners led to the discovery of a highly unusual isomerization that generates a significant quantity of a branched cross-coupling product from an unbranched nucleophile.

In recent years, substantial progress has been made in the development of metal-catalyzed cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles (generally primary or secondary) with alkyl nucleophiles (nearly all primary, with a limited number of secondary and tertiary).1,2 Furthermore, enantioselective variants of some alkyl–alkyl coupling processes have been described,3,4,5 although the success to date has been limited, with one exception,6 to reactions with primary alkyl nucleophiles. Expanding the scope of asymmetric processes to encompass secondary–secondary couplings is one of the key remaining objectives in this field. Herein, we report an advance toward that goal, specifically, enantioselective Negishi reactions of racemic secondary benzylic bromides with achiral secondary cycloalkylzinc reagents (eq 1).

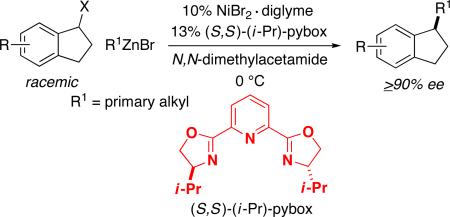

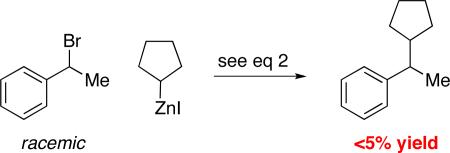

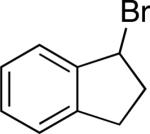

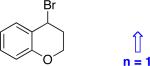

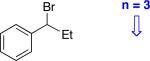

As indicated above, even non-asymmetric cross-couplings between two secondary partners are relatively uncommon;2 nevertheless, we decided to pursue the possibility of developing an enantioselective process. Due to the ready availability and the functional-group compatibility of organozinc reagents, we viewed them as particularly attractive coupling partners.7 Several years ago, we reported that a nickel/pybox catalyst can couple 1-bromoindanes with primary alkylzinc reagents with good ee (eq 2);8 on the other hand, other benzylic bromides, including acyclic electrophiles, cross-couple with more modest enantioselectivity (<80% ee). Perhaps not surprisingly, an attempt to apply this method to the Negishi reaction of an acyclic benzylic bromide with a secondary alkyl-zinc reagent provided a disappointing result (eq 3).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

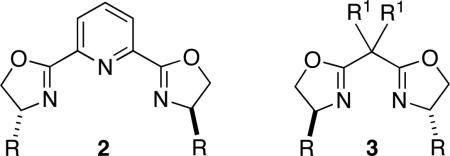

To date, only two classes of chiral ligands (2 and 3) have proved to be useful for asymmetric Negishi reactions of alkyl electrophiles.9,10 However, our attempts to apply these families of ligands to enantioselective secondary–secondary cross-couplings of the type illustrated in eq 3 were unsuccessful.

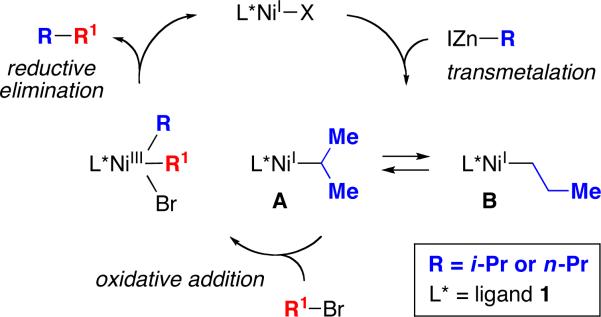

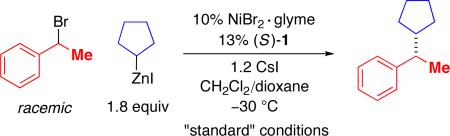

After considerable investigation, we determined that a chiral pyridine–oxazoline ligand furnishes promising results for the desired nickel-catalyzed secondary–secondary cross-coupling (78% ee, 84% yield; Table 1, entry 1). Pyridine–oxazolines have been applied as ligands in a variety of contexts,11 but they have not been employed in cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles. Upon replacing the pyridine with a more extended aromatic ring system, we established that new, readily available isoquinoline–oxazoline ligand 112 provides excellent ee and high yield in the targeted stereoconvergent secondary–secondary cross-coupling of a racemic alkyl electrophile (95% ee, 91% yield; entry 2).

Table 1.

Impact of Reaction Parameters on a Catalytic Enantioselective Secondary–Secondary Cross-Couplinga

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from the “standard” conditions | ee (%) | yield (%)b |

| 1 | (S)-4, instead of (S)-1 | 78 | 84 |

| 2 | none | 95 | 91 c |

| 3 | no NiBr2·glyme | – | <2 |

| 4 | no (S)-1 | – | 9 |

| 5 | no CsI | 93 | 69 |

| 6 | r.t. | 72 | 20 |

| 7 | 5% NiBr2·glyme, 6.5% (S)-1 | 93 | 64 |

| 8 | (S,S)-(i-Pr)-pybox, instead of (S)-1 | – | <2 |

| 9 | (S,S)-5, instead of (S)-1 | 55 | 9 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield determined by GC analysis versus a calibrated internal standard, unless otherwise noted.

Yield of purified product.

Table 1 provides information about the impact of an array of reaction parameters on the efficiency of this new asymmetric secondary–secondary cross-coupling process. In the absence of NiBr2•glyme, essentially no carbon–carbon bond formation is observed (entry 3), whereas, if isoquinoline–oxazoline ligand 1 is omitted, a small amount of coupling occurs (entry 4). The primary effect of the CsI additive is not on ee, but on yield (entry 5).13 If the Negishi reaction is conducted at room temperature, there is a significant deterioration in enantioselectivity and yield (entry 6), while, if less catalyst is employed, only the yield is impacted (entry 7). A pybox9 and a bis(oxazoline)10 ligand are less effective than isoquinoline–oxazoline 1 (entries 8 and 9).

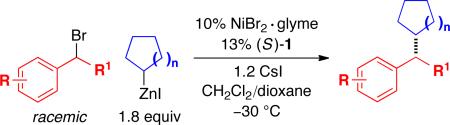

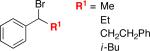

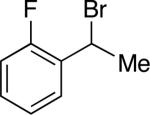

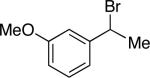

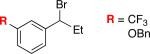

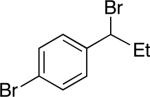

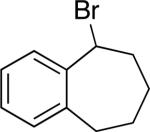

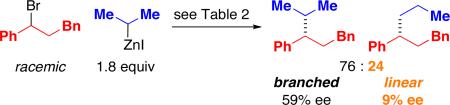

Under our optimized conditions, we can achieve asymmetric secondary–secondary cross-couplings of an array of racemic benzylic bromides with cycloalkylzinc reagents (Table 2).14 Carbon–carbon bond formation proceeds in high ee for electrophiles in which the alkyl substituent (R1) ranges in size from methyl to isobutyl (entries 1–4). Furthermore, the aromatic ring can be ortho-, meta-, or para-substituted, and it can bear an electron-withdrawing or an electron-donating group (entries 5–12). Bicyclic electrophiles, including a heterocycle, undergo secondary–secondary cross-coupling with excellent enantioselectivity (entries 13–15).15 Finally, although we optimized this method with a cyclopentylzinc reagent as the nucleophilic coupling partner, we have determined that a cycloheptylzinc can also be employed with good results (entries 16 and 17).16

Table 2.

Catalytic Enantioselective Secondary–Secondary Cross-Coupling Reactionsa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | electrophile | ee (%) | yield (%)b |

| 1 |

|

95 | 91 |

| 2 | 93 | 84 | |

| 3 | 95 | 72 | |

| 4 | 93 | 75 | |

| 5 |

|

87 | 48 |

| 6 |

|

95 | 86 |

| 7 |

|

91 | 51 |

| 8 | 91 | 65 | |

| 9 |

|

95 | 80 |

| 10 | 92 | 74 | |

| 11c | 91 | 74 | |

| 12 |

|

92 | 68 |

| 13d |

|

96 | 74 |

| 14d |

|

98 | 79 |

| 15d |

|

95 | 54 |

| 16e |

|

87 | 60 |

| 17e |

|

84 | 52 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Yield of purified product.

1.1 equivalents of the organozinc reagent were used.

Mgl2 (1.2 equiv) was used in place of CsI.

3 equivalents of the organozinc reagent were used.

Benzyl ethers, aryl ethers, aryl fluorides, aryl chlorides, and even aryl bromides and iodides17 are compatible with the cross-coupling conditions (Table 2, entries 5, 6, 8, 10–12, 15, and 17). Furthermore, the method is not sensitive to adventitious moisture: for example, the addition of 10 mol% water has no effect on enantioselectivity or yield.

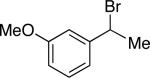

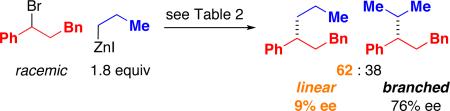

When we apply our method to the cross-coupling of an acyclic secondary alkylzinc reagent, we observe the formation of a substantial quantity of the isomeric (linear) product (eq 4); such a secondary-to-primary isomerization is a common side reaction in cross-couplings of aryl and alkenyl electrophiles.18 Particularly intriguing are the significantly different levels of enantiomeric excess for the branched versus the linear products.

|

(4) |

We next examined the corresponding Negishi reaction wherein primary alkylzinc reagent n-PrZnI is employed as the cross-coupling partner. The ee of the linear product is essentially identical to that obtained in the coupling of i-PrZnI (eq 4 versus eq 5). More surprising is our observation that a substantial proportion (38%) of the cross-coupling product is the branched isomer.

|

(5) |

In our previous studies of alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings, we have never detected the formation of a branched product when a primary alkylmetal reagent was employed as the nucleophilic coupling partner.19 Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there is virtually no precedent more generally in cross-coupling chemistry for the formation of a substantial amount of a branched product from a linear alkylmetal compound.20

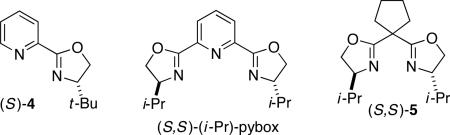

Our working hypothesis is that isomerization proceeds through the interconversion of A and B (Figure 1)21 via β-hydride elimination and β-migratory insertion. The difference in branched:linear product ratios for eq 4 and eq 5 (76:24 and 38:62, respectively) suggests that A and B have not reached equilibrium in both of these reactions. The greater propensity of the nickel/1-catalyzed process to generate the isomeric product, relative to other Negishi couplings that we have described, may be due in part to the use of a bidentate, rather than a tridentate, ligand.22,23

Figure 1.

Outline of a possible mechanism for nickel-catalyzed secondary–secondary cross-couplings.

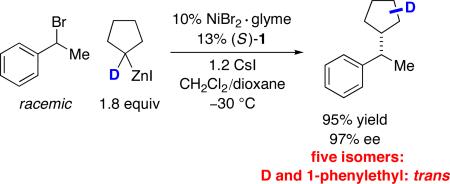

To gain insight into whether β-hydride elimination/β-migratory insertion is also occurring during the cross-coupling of a cyclic secondary nucleophile, we examined the Negishi reaction of a deuterium-labeled cyclopentylzinc reagent (eq 6). Five deuterium-containing coupling products (all with deuterium trans to the 1-phenylethyl substituent on the five-membered ring) were generated in approximately equal quantities, consistent with β-hydride elimination/β-migratory insertion of a cyclopentylnickel intermediate. Furthermore, the high yield and the formation of only trans products indicates that dissociation of cyclopentene from the nickel–olefin complex is not occurring to an appreciable extent during the cross-coupling process.24 In line with this suggestion, when the Negishi reaction is conducted in the presence of 0.5 equivalents of unlabeled cyclopentene, virtually no deuterium-free cross-coupling product is observed.

|

(6) |

In summary, we have described a method for the enantioselective cross-coupling of secondary electrophiles with secondary nucleophiles, specifically, stereoconvergent Negishi reactions of racemic acyclic and cyclic benzylic bromides with achiral alkylzinc reagents (couplings with cyclopentyl- and cycloheptylzinc iodide proceed with excellent ee). Although tridentate pybox ligands have proved optimal in all but one study to date of asymmetric Negishi reactions, attempts to apply this family of ligands to the targeted cross-coupling process were unsuccessful. On the other hand, a new, readily available bidentate isoquinoline-oxazoline was effective, an observation that serves as a useful reminder of the opportunities offered by exploring different classes of ligands. Studies of acyclic alkylzinc reagents led to the discovery of an unusual isomerization that generates a substantial amount of a branched cross-coupling product from an unbranched nucleophile. Efforts to expand the scope of this and related enantioselective cross-coupling processes are underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences: R01–GM62871) and the German Academic Exchange Service (postdoctoral fellowship for J.T.B.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.For some reviews and leading references, see: Glasspoole BW, Crudden CM. Nature Chem. 2011;3:912–913. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1210.Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1417–1492. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p.Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:2656–2670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611.Glorius F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:8347–8349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803509.

- 2.For examples of secondary–secondary coupling reactions, see: Copper-catalyzed (activated electrophile): Malosh CF, Ready JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10240–10241. doi: 10.1021/ja0467768. Nickel-catalyzed (activated electrophile): Smith SW, Fu GC. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:9334–9336. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802784. Copper-catalyzed (unactivated electrophile): Yang C-T, Zhang Z-Q, Liang J, Liu J-H, Lu X-Y, Chen H-H, Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:11124–11127. doi: 10.1021/ja304848n.

- 3.For recent examples of reactions of secondary electrophiles (as a function of their organometallic coupling partner) and leading references, see: Boron: Wilsily A, Tramutola F, Owston NA, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5794–5797. doi: 10.1021/ja301612y. Zinc: Choi J, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9102–9105. doi: 10.1021/ja303442q. Magnesium: Lou S, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1264–1266. doi: 10.1021/ja909689t. Silicon: Dai X, Strotman NA, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3302–3303. doi: 10.1021/ja8009428. Zirconium: Lou S, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5010–5011. doi: 10.1021/ja1017046. Indium: Caeiro J, Sestelo JP, Sarandeses LA. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:741–746. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701035.

- 4.For a recent application in the total synthesis of carolacton (enantioselective Negishi cross-coupling of a racemic allylic chloride), see: Schmidt T, Kirschning A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:1063–1066. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106762.

- 5.For an example of a cobalt-catalyzed asymmetric coupling of a tertiary alkyl bromide with an allylmagnesium reagent that proceeds in 22% ee and 49% yield, see: Tsuji T, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:4137–4139. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4137::AID-ANIE4137>3.0.CO;2-0.

- 6.Zultanski SL, Fu GCJ. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15362–15364. doi: 10.1021/ja2079515. A single example of an asymmetric secondary–secondary cross-coupling is described, specifically, a Suzuki reaction of an unactivated alkyl bromide with cyclopropyl-(9-BBN) that proceeds in 84% ee and 70% yield.

- 7.For a review, see: Negishi E.-i., Hu Q, Huang Z, Wang G, Yin N. In: The Chemistry of Organozinc Compounds. Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. Wiley; New York: 2006. Chapter 11.

- 8.Arp FO, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10482–10483. doi: 10.1021/ja053751f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For applications of pybox ligands, see: Fischer C, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4594–4595. doi: 10.1021/ja0506509. Ref. 8. Son S, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2756–2757. doi: 10.1021/ja800103z.Smith SW, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12645–12647. doi: 10.1021/ja805165y.Lundin PM, Esquivias J, Fu GC. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:154–156. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804888.Oelke AJ, Sun J, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2966–2969. doi: 10.1021/ja300031w.

- 10.For an application of a bis(oxazoline), see Ref. 3b.

- 11.For initial reports of the use of chiral pyridine–oxazoline ligands in asymmetric catalysis, see: Brunner H, Obermann U. Chem. Ber. 1989;122:499–507.Nishiyama H, Sakaguchi H, Nakamura T, Horihata M, Kondo M, Itoh K. Organometallics. 1989;7:846–848. For a recent application of a chiral pyridine–oxazoline ligand in palladium-catalyzed conjugate additions of arylboronic acids to cyclic enones, see: Kikushima K, Holder JC, Gatti M, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6902–6905. doi: 10.1021/ja200664x. For a review of applications of oxazoline-containing ligands in asymmetric catalysis, see: Hargaden GC, Guiry PJ. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2505–2550. doi: 10.1021/cr800400z.

- 12.To the best of our knowledge, isoquinoline–oxazoline ligand 1 has not previously been reported. It is prepared in one step from isoquinoline-1-carbonitrile and t-leucinol.

- 13.a For a previous report of the beneficial effect of a halide salt on an enantioselective cross-coupling of an alkyl electrophile, see: Ref. 9c. Possible explanations for the beneficial effect of the halide salt include in situ formation of a benzylic iodide and the generation of more reactive zincate complexes (for a recent discussion and leading references regarding zincate adducts, see: McCann LC, Hunter HN, Clyburne JAC, Organ MG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:7024–7027. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203547.

- 14.Under our standard conditions, a benzylic chloride was not a suitable cross-coupling partner (high ee, low yield), and hindered electrophiles (e.g., R1 = isopropyl in Table 2) couple in significantly lower yield.

- 15.The use of CsI rather than MgI2 led to slightly diminished ee and yield.

- 16.Under our standard conditions, cyclohexylzinc iodide cross-couples with 1-bromo-1-phenylpropane in 54% yield and <5% ee; however, by further optimizing this process, we have been able to generate the desired product in up to 61% ee.

- 17.For leading references to nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings wherein C–O (and C–F) bonds are cleaved, see: Rosen BM, Quasdorf KW, Wilson DA, Zhang N, Resmerita A-M, Garg NK, Percec V. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1346–1416. doi: 10.1021/cr100259t. Cross-couplings of aryl chlorides, and especially aryl bromides and iodides, are commonplace.

- 18.For studies of nickel-catalyzed couplings of secondary alkyl nucleophiles with aryl or alkenyl electrophiles, see: Tamao K, Kiso Y, Sumitani K, Kumada M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:9268–9269.Hayashi T, Konishi M, Kobori Y, Kumada M, Higuchi T, Hirotsu K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:158–163.Joshi-Pangu A, Ganesh M, Biscoe MR. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1218–1221. doi: 10.1021/ol200098d.

- 19.For leading references, see Ref. 3a and Ref. 3b.

- 20.For a report of primary-to-secondary isomerization (2%) in a palladium-catalyzed Negishi reaction, see: Han C, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7532–7533. doi: 10.1021/ja902046m.

- 21.For early mechanistic studies of nickel-catalyzed Negishi reactions of unactivated alkyl electrophiles, see: Jones GD, Martin JL, McFarland C, Allen OR, Hall RE, Haley AD, Brandon RJ, Konovalova T, Desrochers PJ, Pulay P, Vicic DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13175–13183. doi: 10.1021/ja063334i.Phapale VB, Buñuel E, García-Iglesias M, Cárdenas DJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:8790–8795. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702528.Lin X, Phillips DL. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3680–3688. doi: 10.1021/jo702497p.

- 22.Only one report of asymmetric Negishi reactions of alkyl electrophiles has employed a bidentate, rather than a tridentate, ligand (Ref. 3b). All else being equal, β-hydride elimination may be more facile in the case of lower-coordinate nickel complexes.

- 23.For alkyl–alkyl cross-couplings, if transmetalation precedes oxidative addition (e.g., Figure 1), there may be a greater propensity for isomerization of the alkyl group derived from the nucleophile, relative to isomerization of the alkyl group derived from the electrophile and relative to mechanisms wherein oxidative addition occurs first.

- 24.The data in eq 6 also suggest that reversible homolysis of the Ni–cyclopentyl bond is probably not occurring during the course of the cross-coupling.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.