Abstract

Synthetic stimulants commonly sold as “bath salts” are an emerging abuse problem in the U.S. Users have shown paranoia, delusions, and self-injury. Previously published in vivo research has been limited to only two components of bath salts (mephedrone and methylone). The purpose of the present study was to evaluate in vivo effects of several synthetic cathinones found in bath salts and to compare them to those of cocaine (COC) and methamphetamine (METH). Acute effects of methylenedioxyphyrovalerone (MDPV), mephedrone, methylone, methedrone, 3-fluoromethcathinone (3-FMC), 4-fluoromethcathinone (4-FMC), COC, and METH were examined in male ICR mice on locomotor activity, rotorod, and a functional observational battery (FOB). All drugs increased locomotor activity, with different compounds showing different potencies and time courses in locomotor activity. 3-FMC and methylone decreased performance on the rotorod. The FOB showed that in addition to typical stimulant induced effects, some synthetic cathinones produced ataxia, convulsions, and increased exploration. These results suggest that individual synthetic cathinones differ in their profile of effects, and differ from known stimulants of abuse. Effects of 3-FMC, 4-FMC, and methedrone indicate these synthetic cathinones share major pharmacological properties with the ones that have been banned (mephedrone, MDPV, methylone), suggesting that they may be just as harmful.

Keywords: locomotor activity, MDPV, mephedrone, methylone, mouse, synthetic cathinones

1. Introduction

An emerging substance abuse problem is abuse of synthetic research chemicals for their stimulant properties (DEA, 2011; Psychonaut, 2009). These products, commonly labeled as “bath salts” or “plant food,” are administered through insufflation, oral, smoking, rectal and intravenous methods (Psychonaut, 2009; Winstock et al., 2011) and can be purchased legally in most states on the internet, at head shops, or at gas stations (DEA, 2011; Karila and Reynaud, 2010; Schifano et al., 2011; Winstock et al., 2010a, 2011). The active components contained in bath salts are synthetic cathinone analogs. Within the first eight months that bath salts were on the U.S. drug market, there were more than 1400 cases of misuse and abuse reported to U.S. poison control centers in 47 of 50 states (Spiller et al., 2011). The number of calls to poison control centers in the U.S. regarding bath salts rose from 303 in 2010 to 6072 in 2011 (American Association of Poison Control Centers, 2012). The growing prevalence of bath salt use makes them a major health concern throughout the U.S. and Europe.

Cathinone is naturally occurring in the leaves of the khat plant (Catha edulis), which grows in eastern Africa and southern Arabia where it is used for its amphetamine-like effects (Griffiths et al., 2010). In rats, cathinone produces locomotor increases similar to those produced by amphetamine (Kalix, 1992), and increases extracellular dopamine (Pehek et al., 1990). The synthetic cathinones that have been found in bath salts include, but are not limited to 3-FMC (3-fluoromethcathinone), 4-FMC (4-fluoromethcathinone), buphedrone (α-methylaminobutyrophenone), butylone (beta-keto-N-methyl-3,4-benzodioxyolybutanamine), MDPV (methylenedioxyphyrovalerone), mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone), methedrone (4-methoxymethcathinone), methylone (3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone), and naphyrone (naphthylpyrovalerone) (Karila and Reynaud, 2010). MDPV, mephedrone, and methylone are the most commonly found active components worldwide (ACMD, 2010; EMCDDA, 2010; Spiller et al., 2011), with MDPV being the most commonly found component in the U.S. (Spiller et al., 2011).

To the extent that the in vivo effects of synthetic cathinones have been examined, they have been found to share pharmacological properties with other abused drugs that increase levels of monoamine neurotransmitters [e.g., stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine]. For example, a low dose of mephedrone (3 mg/kg) produced moderate increases in locomotor activity in rats (Kehr et al., 2011), and higher doses (10 mg/kg and 30 m/kg) produced significant locomotor increases in mice (Angoa-Perez et al, 2012). Acquisition of mephedrone self-administration also has been demonstrated (Hadlock et al., 2011). Anecdotal and case reports of human use of bath salts suggest these substances produce powerful psychological effects, including psychotic behavior, paranoia, delusions, hallucinations, and self-injury (EMCDDA, 2010; Spiller et al., 2011; Striebel and Pierre, 2011). In addition, since 2010, multiple cases of death while under the influence of bath salts in the U.S. have occurred, including some suicides (CDC, 2011; Spiller et al., 2011). Based on poison control center reports and case studies in the U.S., MDPV in particular tends to produce increased aggression, hallucinations, and paranoia (Antonowicz et al., 2011; Spiller et al., 2011). While these data suggest that the abuse liability and pharmacological effects of synthetic cathinones is likely similar to that of known stimulants of abuse, additional data are needed with a broader range of compounds that have been identified in purchased products.

Although some active components in bath salts have already been made illegal in some states (DEA, 2011; Spiller et al., 2011), and the DEA put an emergency ban on MDPV, mephedrone, and methylone in October 2011, it is likely that manufacturers will continue to make slight alterations in the chemical structure of these compounds in order to avoid detection and allow legal sale (Wohlfarth and Weinmann, 2010). This strategy is not without precedence, as Europe has seen the appearance of new bath salt products containing alternative cathinones following earlier legal restrictions (Camilleri et al., 2010). After legislative bans in Europe on MDPV and mephedrone, naphyrone has become the most commonly used bath salt in Europe. It is expected that once naphyrone becomes a controlled substance, a new compound will be ready for export to replace it (Eastwood, 2010).

The primary purpose of the present study was to evaluate the in vivo effects of synthetic cathinones that have been found in bath salts in the U.S. and to compare these effects to those produced by cocaine and methamphetamine. Cocaine is primarily a monoamine transporter blocker/reuptake inhibitor, and methamphetamine is primarily a monoamine transporter substrate/releaser (Fleckenstein et al., 2000; Rothman et al., 2001). Compounds identified in bath salts have been shown to be either cocaine-like monoamine reuptake inhibitors, methamphetamine-like releasers, or a hybrid of both mechanisms (Baumann et al., 2012; Cozzi et al. 1999; Martinez-Clemente et al., 2012; Meltzer et al., 2006; Nagai et al., 2007; Psychonaut, 2009; Winstock et al., 2010a).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Male ICR mice (Harlan) (n=8/group) were individually housed in clear plastic cages in a temperature-controlled environment (20-24°C) with a 12 hr light-dark cycle (lights on at 6 a.m.). Mice had ad libitum access to water and food in their home cages at all times, and were approximately 47-56 days old at the beginning of the study. Research reported in this manuscript was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at RTI International, and followed the principles of laboratory animal care (National Research Council, 2003).

2.2 Apparatus

Locomotor sessions were conducted in open field activity chambers made of clear Plexiglas measuring 33.0cm × 51.0cm × 23.0cm. Beam breaks were recorded by San Diego Instruments Photobeam Activity System software (model SDI: V-71215, San Diego, CA) on a computer located in the experimental room. The apparatus contained two 4-beam infrared arrays that measured horizontal movement. A standard rodent rotorod apparatus was used to measure motor coordination (Stoelting, model 52790). The rotorod revolved at 10 revolutions per min, and reached this speed over the course of the first 30 s of the trial. Trials lasted a maximum of 150 s. Assessment in a functional observational battery (FOB) took place in a clear Plexiglas open field measuring 33.0cm × 51.0cm × 23.0cm, and during handling.

2.3 Procedure

Mice were randomly assigned to a drug group and a particular dose of that drug. In addition, a single saline control group was assessed for comparison to each drug group. Mice were tested for locomotor activity during week 1, trained to walk in the rotorod apparatus during week 2, and tested on the rotorod apparatus, followed by an FOB, in week 3. They were administered two drug injections during the experiment, once during week 1, and once during week 3. Doses examined were saline, 10-42 mg/kg cocaine, 1-10 mg/kg methamphetamine, 1-30 mg/kg MDPV, 10-56 mg/kg of 4-FMC and methedrone, and 3-56 mg/kg 3-FMC, mephedrone, and methylone. All drugs were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.), and doses were chosen based on previous in vivo research on mephedrone (Angoa-Perez et al, 2012; Hadlock et al., 2011; Kehr et al., 2011). Doses administered to each group of mice throughout the experiment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Doses (in mg/kg) administered to each group of mice (n=8) for the locomotor and rotorod/FOB portions of the experiment.

| Group | Locomotor | Rotorod/FOB |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saline | Saline |

| 2 | 10.0 3-FMC | 10.0 3-FMC |

| 3 | 10.0 4-FMC | 10.0 4-FMC |

| 4 | 30.0 COC | 30.0 COC |

| 5 | 10.0 MDPV | 10.0 MDPV |

| 6 | 10.0 Mephe | 10.0 Mephe |

| 7 | 3.0 METH | 3.0 METH |

| 8 | 10.0 Methe | 10.0 Methe |

| 9 | 10.0 Methy | 10.0 Methy |

| 10 | 17.0 3-FMC | 30.0 4-FMC |

| 11 | 17.0 4-FMC | 30.0 3-FMC |

| 12 | 42.0 COC | 10.0 COC |

| 13 | 17.0 MDPV | 3.0 MDPV |

| 14 | 30.0 Mephe | 30.0 Mephe |

| 15 | 5.6 METH | 10.0 METH |

| 16 | 30.0 Methe | 30.0 Methe |

| 17 | 30.0 Methy | 30.0 Methy |

| 18 | 17.0 MDPV* | 56.0 3-FMC |

| 19 | 30.0 4-FMC | 56.0 4-FMC |

| 20 | 17.0 COC | 17.0 COC |

| 21 | 30.0 3-FMC | 30.0 MDPV |

| 22 | 30.0 Mephe* | 56.0 Mephe |

| 23 | 5.6 METH* | 1.0 METH |

| 24 | 30.0 Methe* | 56.0 Methe |

| 25 | 17.0 Methy | 56.0 Methy |

| 26 | 3.0 MDPV | - |

| 27 | 3.0 Mephe | - |

| 28 | 3.0 Methy | - |

| 29 | 3.0 3-FMC | - |

| 30 | 10.0 COC | - |

| 31 | 1.0 METH | - |

| 32 | 1.0 MDPV | - |

Data were excluded due to replication of the same dose.

Groups 26-32 were not included in the rotorod/FOB assessment.

Abbreviations: COC = cocaine; METH = methamphetamine; 3-FMC = 3-fluoromethcathinone; 4-FMC = 4-fluoromethcathinone; MDPV = methylenedioxyphyrovalerone; Mephe = mephedrone; Methe = methedrone; Methy = methylone.

On the first test day, mice were injected with their assigned drug dose and immediately placed into locomotor activity chambers for a 90-min test. Training on the rotorod occurred the following week. Mice were trained to walk on the rotorod on two nonconsecutive days that took place the week before their rotorod test day. For rotorod training day 1, mice were placed on the rotorod. If they fell off, they were placed back on the rotorod immediately. Mice were repeatedly put back on the rotorod if they fell off until they completed two 150-s trials on the rod without falling off, or until 30 min of training was completed, whichever occurred first. Rotorod training day 2 was identical to training day 1 except the maximum training time was 20 min. On the rotorod test day, a 150-s rotorod test was conducted at 15 min post-injection. Rotorod tests were used to evaluate motor coordination, balance (Forster and Lal, 1999; Steinpreis et al., 1999; Walsh and Wagner, 1992), and neurotoxicity (Jatav et al., 2008).

Immediately after the rotorod test, an FOB was used to classify observable effects of the drugs (20 min post-injection). The FOB was modified from a procedure commonly used by the Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA, 1998a, 1998b). This observational battery provides an overall behavioral profile of the effects of each compound with an emphasis on detection of potential safety concerns, and allows assessment of a wide range of drug effects. FOBs were scored by a single trained technician who was not blind to treatment. Mice were observed in pairs (each mouse was observed in a separate chamber), and each FOB took place over 5 min. All measures were scored using an ordinal scale, with 1 = normal/no drug effect, 2 = minor-moderate drug effect, and 3 = major drug effect. The first 1 min was reserved for acclimation, and observations were taken during the remaining 4 min. Observations were taken on ataxia (lacking coordination of muscle movements, as in walking), retropulsion (walking backward), exploration (e.g. reorienting the head and sniffing), convulsions (whole body tremors), circling (repeated movement of the animal in a circular manner), excessive grooming (prolonged bouts of grooming, or grooming in a stereotypic manner), flattened body posture (e.g., midsection low to ground, sometimes showing limb splaying), hyperactivity (fast movement of the entire body), salivation (wetness around mouth or chin), self-injury (biting or pulling on skin that produces lesions or bleeding), Straub tail (tail is held in a vertical or nearly vertical position), stereotyped head weaving (repetitive turning of the head from side to side), stereotyped circular head movements (moving the head in repetitive circular motions), stereotyped biting (repeatedly biting objects other than oneself such as the Plexiglas chamber), stereotyped licking (repeatedly licking objects other than oneself such as the Plexiglas chamber), other stereotyped compulsive movements (any repetitive movement that does not fall under other categories of stereotyped behavior), stimulation (e.g., tense body, sudden darting), and tremor (rhythmical, repetitive flexing of muscles).

2.4 Drugs

Cocaine and methamphetamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. 3-FMC, 4-FMC, MDPV, mephedrone, methedrone, and methylone were synthesized in house using standard synthetic procedures. All compounds were formulated as recrystalized salts and were > 97% pure. The purity was assessed by several analytical techniques including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen (CHN) combustion analysis and proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. All drugs were dissolved in physiological saline. Doses of all drugs are expressed as mg/kg of the salt, and were administered at a volume of 10 ml/kg. Saline was used as a comparison for all drugs.

2.5 Data Analysis

2.5.1 Locomotor activity and Rotorod Data Analysis

Locomotor activity was expressed as the total number of beam breaks for each 10-mins within the 90-min session. Mixed model ANOVAs were used to analyze the time course of the drugs on locomotor activity, with time as the within-subject factor and dose as the between-subject factor. One way ANOVAs with dose as the between subjects factor were also used to analyze time on the rotorod. Following significant ANOVAs, Tukey post hoc tests were used to determine differences between means. All tests were considered significant at p < 0.05.

2.5.2 FOB Data Analysis

All FOB data were analyzed with Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVAs by ranks for each dependent measure, corrected for ties. Because there were 18 dependent variables for FOB, the alpha level was controlled for this number of measures (α = 0.0027). Tukey post hoc tests were used to determine differences between means. Statistical analyses of effects of 56 mg/kg methylone were limited to only 4 subjects because this dose induced convulsions in the first 4 subjects, and was therefore not administered to the other subjects in the group.

3. Results

3.1 Locomotor activity

Figure 1 shows effects of each compound on locomotor activity compared to the saline group. For ease of comparison, the results of the saline group are shown in each panel. Over the course of the 90 min session, habituation occurred in the saline group, resulting in attenuation of activity in later bins (compared to bin 1). Data in each panel of the figure were analyzed with a separate mixed model ANOVA, with use of the same saline group. As a consequence of differences in magnitude of drug effect and within-group variance for each drug, the specific time points at which these decreases in activity in the saline group were significant varied somewhat for each analysis (despite use of the same data). Therefore, within each analysis, emphasis is placed on discussion of differences across drug doses (compared to saline) rather than across bins. The habituation data are important only insofar as changes in locomotor activity over time in the saline group should be taken into consideration when interpreting changes in activity over time in the each drug group.

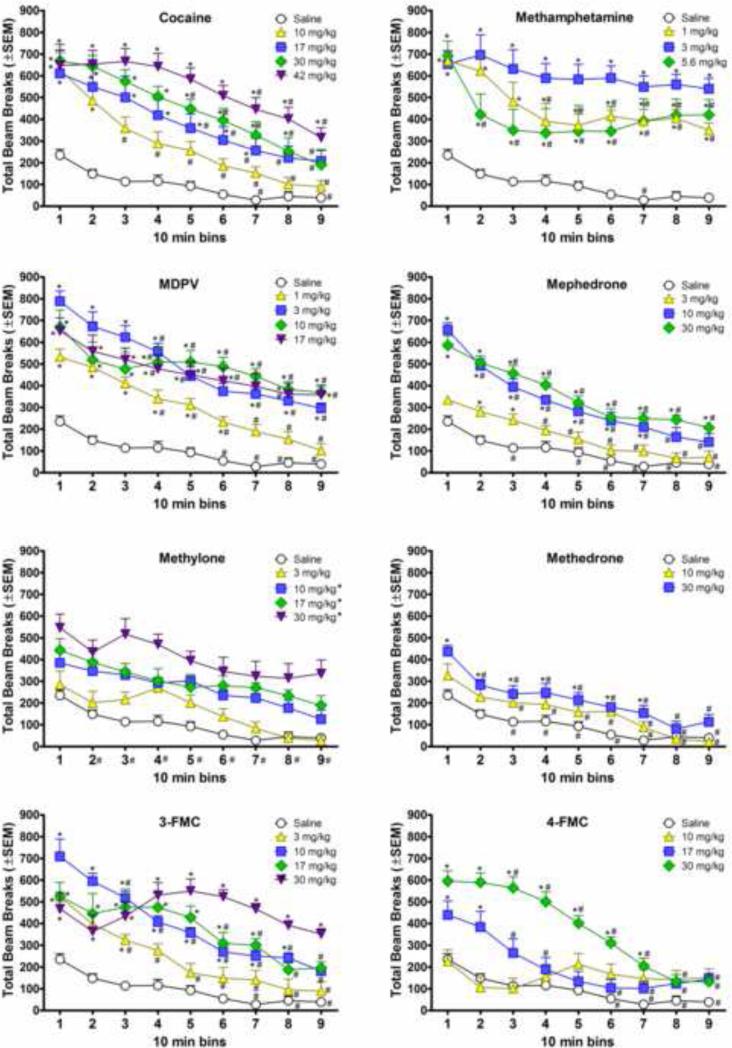

Figure 1.

Effects of synthetic cathinones and known stimulants of abuse (cocaine and methamphetamine) on locomotor activity, plotted as a function of 10 min time bins during a 90-min test session. Values represent average (± SEM) number of beam breaks for each dose (n=8 per dose). Asterisks within each panel represent doses that produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline during the same time bin. Pound signs within each panel represent significant attenuation of the effect of the dose compared to its initial effect during the first 10 min of the session. For methylone, asterisks within the legend and pound signs beside minutes on the X-axis indicate significant main effects for dose compared to saline (both collapsed across bins) and for the first 10 min compared to the last 10 min (collapsed across dose), respectively.

For cocaine, there was a significant effect of dose [F (4, 35) = 13.76, p < 0.001], a significant effect of time [F (8, 280) = 77.27, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (32, 280) = 2.93, p < 0.001]. The interaction revealed that 10-42 mg/kg cocaine produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline across the first 30 min of the session. At 30-60 min of the session, 17-42 mg/kg cocaine significantly increased locomotor activity whereas only 30 and 42 mg/kg produced significant increases at 70-80 min and only 42 mg/kg continued to produce significant increases 80-90 min post-injection. Significant habituation (compared to the first 10 min) occurred in the saline group during 60-70 and 80-90 min. The time at which significant attenuation of the effect of cocaine in the initial 10 min was observed was dose-dependent and occurred at 20-90 min for the 10 mg/kg dose, at 40-90 min for the 17 and 30 mg/kg doses, and at 60-90 min for the 42 mg/kg dose.

For methamphetamine, there was a significant effect of dose [F (3, 28) = 14.20, p < 0.001], a significant effect time [F (8, 224) = 17.36, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (24, 224) = 2.16, p < 0.01]. The interaction revealed that 1-5.6 mg/kg methamphetamine produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline at all time points across the session. Significant habituation occurred in the saline group during 60-70 min after the session start. Significant attenuation of the methamphetamine-induced increase in beam breaks was observed at 30-90 min and 10-90 min of the session in mice that received the 1 and 5.6 mg/kg doses, respectively. In contrast, the 3 mg/kg dose produced sustained increases in locomotor activity that occurred during the first 10 min and were not altered across the entire session.

For MDPV, there was a significant effect of dose [F (4, 35) = 24.13, p < 0.001], a significant effect of time [F (8, 280) = 64.18, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (32, 280) = 2.80, p < 0.001]. The interaction revealed that 3-17 mg/kg MDPV produced significant increases in beam breaks (compared to saline) during each 10 min bin in the session. In addition, the 1 mg/kg dose significantly increased locomotor activity compared to saline for 60 min after the session start. Significant habituation (compared to the first 10 min) occurred in the saline-treated group at 50-90 min of the session. Significant attenuation of MDPV's stimulant action during the first 10 min of the session was observed at 30-90 min at the 1, 3 and 17 mg/kg doses and at 20-30 and 50-90 min of the session in mice that were treated with the 10 mg/kg dose.

For mephedrone, there was a significant effect of dose [F (3, 28) = 35.49, p < 0.001], a significant effect time [F (8, 224) = 110.52, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (24, 224) = 4.68, p < 0.001]. The interaction revealed that all doses of mephedrone produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline during one or more time points. Compared to saline, 10 mg/kg mephedrone significantly increased locomotor activity during the first 70 min of the session, whereas the 3 mg/kg dose produced significant increases only during 20-40 min post-injection. The 30 mg/kg dose of mephedrone significantly stimulated locomotor activity for the entire session (compared to saline). Compared to activity during the initial 10 min of the session, significant habituation occurred in the saline-treated group at 20-30 min and 40-90 min after session start. Significant attenuation of the initial stimulant effect of each dose was observed at 30-90 min for 3 mg/kg, 10-90 min for 10 mg/kg, and 20-90 min for 30 mg/kg.

For methylone, there was a significant effect of dose [F (4, 35) = 14.22, p < 0.001], a significant effect of time [F (8, 280) = 36.22, p < 0.001], but no significant interaction. The main effects for dose and minutes in the session revealed that 10-30 mg/kg methylone produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline collapsed across time points, and that activity during the first 10 min was significantly different from all other time points collapsed across doses.

For methedrone, there was a significant effect of dose [F (2, 21) = 8.89, p < 0.001], a significant effect time [F (8, 168) = 51.51, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (16, 168) = 1.71, p < 0.05]. The interaction revealed that 30 mg/kg methedrone produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline during the first 70 min of the session. Significant attenuation of the stimulant effect observed in the first 10 min of the session occurred during each subsequent 10 min. Significant habituation occurred at 20-90 min compared to the first 10 min in mice treated with saline or with 10 mg/kg methedrone.

For 3-FMC, there was a significant effect of dose [F (4, 35) = 20.55, p < 0.001], a significant effect time [F (8, 280) = 25.82, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (32, 280) = 6.42, p < 0.001]. The interaction revealed that 30 mg/kg 3-FMC produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline during the entire 90-min session. Lower doses of 3-FMC also significantly increased beam breaks, but for shorter amounts of time. The 3 mg/kg dose produced significantly increased locomotor activity for the first 30 min of the session; the 10 mg/kg dose, for the first 80 min of the session; and the 17 mg/kg dose for the first 70 min of the session. Significant habituation in the saline-treated mice occurred during 60-90 min after session start. At 20-90 min of the session, locomotor activity was significantly decreased compared to the first 10 min for doses of 3 and 10 mg/kg 3-FMC, although activity remained elevated compared to saline at these doses for some of this time. Significant attenuation of the stimulant effect of 17 mg/kg 3-FMC occurred at 50-90 min after the start of the session. In contrast, the stimulant effect of 30 mg/kg showed no significant alteration over the entire 90-min session.

For 4-FMC, there was a significant effect of dose [F (3, 28) = 16.33, p < 0.001], a significant effect time [F (8, 224) = 41.17, p < 0.001], and a significant interaction [F (24, 224) = 9.83, p < 0.001]. The interaction revealed that 30 mg/kg 4-FMC produced significant increases in beam breaks compared to saline during the first 70 min of the session, whereas the 17 mg/kg dose significantly increased activity only during the first 20 min of the session. In contrast, the 10 mg/kg dose of 4-FMC did not significantly affect locomotor activity compared to saline. Significant attenuation of the initial stimulant effects of 17 and 30 mg/kg occurred at 20-90 min and 40-90 min, respectively. Significant habituation was observed in saline-treated mice at 50-90 min of the session.

3.2 Rotorod

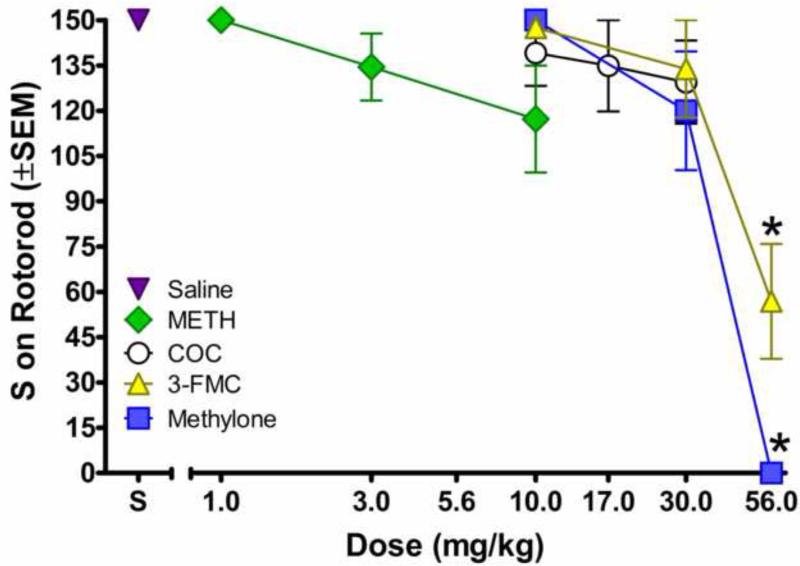

Figure 2 shows effects of compounds on time spent on the rotorod. In contrast with their stimulant effects on locomotor activity, 4-FMC, MDPV, mephedrone, and methedrone did not affect time spent on the rotorod (data not shown). Similarly, cocaine and methamphetamine also did not affect rotorod performance. In contrast, 3-FMC and methylone decreased time on the rotorod [3-FMC: F (3, 31) = 10.47, p < 0.001; methylone: F (3, 28) = 26.63, p < 0.001]. 56 mg/kg 3-FMC and methylone significantly decreased seconds on the rotorod compared to vehicle. When subjects were administered 56 mg/kg methylone, they fell off the rotorod immediately.

Figure 2.

Average latency to fall off the rotorod in seconds plotted as a function of dose of drug. Asterisks indicate significant differences from saline. “S” stands for saline vehicle, COC stands for cocaine, and METH stands for methamphetamine.

3.3 FOB

Results of the FOB are displayed in Table 2. None of the compounds tested produced death, significant effects on retropulsion, excessive grooming, flattened body posture, stereotyped compulsive biting or licking, Straub tail or self-injury; however, one mouse administered 56 mg/kg methylone and one mouse administered 30 mg/kg 3-FMC displayed self-injury in the form of pulling on the skin of the chest with both front paws which produced lesions. 3-FMC produced significant ataxia [H (3) = 16.59, p < 0.0027], with 10 mg/kg showing effects significantly different from vehicle.

Table 2.

Effects of each compound on dependent variables (DV) from the FOB. Arrows denote a difference from saline with corrected alpha level (p < 0.0027). Doses (in mg/kg) at which effect occurred are shown below arrows. For comparison purposes, doses at which locomotor activity was significantly increased during the first 10-min bin of the locomotor activity sessions (Fig. 1) are also shown.

| DV | COC | METH | 3-FMC | 4-FMC | MDPV | Mephe | Methe | Methy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotion (first 10 min) | 10 - 42 | 1 - 5.6 | 3 - 30 | 17 - 30 | 1 -17 | 10 - 30 | 30 | 10 - 30* |

| Ataxia | ↑ | |||||||

| 10 | ||||||||

| Exploration | ↑ | ↑ | ||||||

| 30 | 1 - 30 | |||||||

| Convulsions | ↑ | |||||||

| 56 | ||||||||

| Circling | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| 10 - 42 | 1 - 10 | 3 - 56 | 10 - 56 | 1 - 30 | 3 - 56 | 10 & 30 | ||

| Hyperactivity | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 - 42 | 1 - 10 | 3 - 56 | 10 - 56 | 1- 30 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | |

| Salivation | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ||||

| 10 | 30 & 56 | 30 - 56 | 30 - 56 | |||||

| Head Weaving | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 & 17 | 1 - 10 | 30 - 56 | 30 - 56 | 1 - 30 | 3 & 30 | 3 - 56 | 10 - 30 | |

| Head Circling | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 - 42 | 1 - 10 | 3 - 56 | 10 - 56 | 1- 30 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | |

| Comp Movmts | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||||

| 3 - 5.6 | 30 | 3 - 10 | ||||||

| Stimulation | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 - 42 | 1 - 10 | 3 - 56 | 10 - 56 | 1- 30 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | 3 - 56 | |

Methylone locomotor activity main effect of dose across all bins.

Abbreviations: COC = cocaine; METH = methamphetamine; 3-FMC = 3-fluoromethcathinone; 4-FMC = 4-fluoromethcathinone; MDPV = methylenedioxyphyrovalerone; Mephe = mephedrone; Methe = methedrone; Methy = methylone. Comp Movmts = stereotyped compulsive movements.

3-FMC and MDPV both produced significant increases in exploration [3-FMC: H (3) = 21.25, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 18.36, p < 0.0027]. All doses of MDPV produced this effect, as did 30 mg/kg 3-FMC. The highest dose (56 mg/kg) of methylone produced convulsions in all 4 mice tested with this dose [H (3) = 15.00, p < 0.0027].

Cocaine, methamphetamine, 3-FMC, 4-FMC, MDPV, methedrone, and methylone produce significant increases in circling [cocaine: H (3) = 20.05, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (3) = 20.67, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 21.25, p < 0.0027; 4-FMC: H (3) = 24.88, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 23.85, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 24.58, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 16.34, p < 0.0027]. All doses of all of these compounds produced significant increases in circling compared to saline, except methylone, which only showed significant increases at 10 and 30 mg/kg.

All compounds tested produced significant increases in hyperactivity [cocaine: H (3) = 17.68, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (3) = 20.80, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 21.12, p < 0.0027; 4-FMC: H (3) = 14.77, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 23.83, p < 0.0027; mephedrone: H (3) = 16.87, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 16.87, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 16.16, p < 0.0027]. All doses of all compounds produced significant differences from saline.

Excessive salivation was produced by methamphetamine, 3-FMC, methedrone, and methylone [methamphetamine: H (3) = 25.66, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 21.24, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 26.18, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 15.89, p < 0.0027]. 10 mg/kg methamphetamine, and 30 and 56 mg/kg 3-FMC, methedrone, and methylone produced significant increases in salivation compared to saline.

All compounds tested produced significant increases in stereotyped head weaving [cocaine: H (3) = 23.47, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (3) = 18.96, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 29.31, p < 0.0027; 4-FMC: H (3) = 24.14, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 15.81, p < 0.0027; mephedrone: H (3) = 19.63, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 21.11, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 17.97, p < 0.0027], and stereotyped head circling [cocaine: H (3) = 22.36, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (3) = 23.63, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 23.67, p < 0.0027; 4-FMC: H (3) = 20.77, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 23.68, p < 0.0027; mephedrone: H (3) = 21.81, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 20.51, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 16.38, p < 0.0027]. Doses of 30-56 mg/kg 3-FMC and 4-FMC, 10-17 mg/kg cocaine, 3 and 30 mg/kg MDPV, 10-30 mg/kg methylone, and all doses of mephedrone, methamphetamine, and methedrone produced significant increases in stereotyped head weaving compared to saline. All doses of all compounds produced significant increases from saline for stereotyped head circling.

3-FMC, MDPV, and methamphetamine produced significant increases in other forms of stereotyped compulsive movements [3-FMC: H (3) = 16.52, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 25.34, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (2) = 14.24, p < 0.0027]. 30 mg/kg 3-FMC, 3-10 mg/kg MDPV, and 3-5.6 mg/kg methamphetamine producing significant increases in stereotyped compulsive movements compared to saline.

All compounds tested produced significant increases in stimulation [cocaine: H (3) = 20.05, p < 0.0027; methamphetamine: H (3) = 25.38, p < 0.0027; 3-FMC: H (3) = 21.91, p < 0.0027; 4-FMC: H (3) = 24.91, p < 0.0027; MDPV: H (3) = 25.46, p < 0.0027; mephedrone: H (3) = 23.95, p < 0.0027; methedrone: H (3) = 25.19, p < 0.0027; methylone: H (3) = 18.14, p < 0.0027]. All doses of all compounds produced significant increases in stimulation compared to saline.

4. Discussion

A defining behavioral characteristic of psychomotor stimulants is their propensity to increase locomotion in rodents, an effect that is strongly associated with their high addiction potential (Calabrese, 2008; Wise and Bozarth, 1987). All synthetic cathinones tested in the present study shared this effect, with different cathinones showing different potencies, magnitudes of stimulation, and durations of action. While cathinones increased locomotor activity, the majority of them did not produce any impairment in coordination or balance as shown in performance on the rotorod. The most pronounced stimulation during the initial 10 min of the session was produced by cocaine, methamphetamine, MDPV, mephedrone, and 3-FMC, whereas methedrone produced the weakest initial stimulation. Of the compounds with maximal stimulant activity, methamphetamine and MDPV appeared to have the greatest rank order potency, albeit not all compounds were tested at lower doses. These results generally are consistent with those of past research on synthetic cathinones; however, in vivo evaluation of these compounds to date has been very sparse. For example, mephedrone and methylone have been reported to increase locomotor activity in rats (Baumann et al., 2012; Kehr et al., 2011; Motbey et al., 2011), and mephedrone has also been shown to increase locomotor activity in mice (Angoa-Perez et al., 2012). Similarly, naturally occurring cathinone derived from Catha edulis (khat) has been shown to stimulate motor activity in mice (Zelger et al, 1980). To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate in vivo effects of methedrone, 3-FMC, and 4-FMC, and the first to examine effects of all six cathinones on rotorod performance and in an FOB.

Onset of the locomotor stimulation produced by synthetic cathinones and known stimulants following systemic administration occurred fairly rapidly and was already evident for all compounds during the first 10 min of the session as compared to saline, indicating that the onset of effects was quick since sessions began immediately after injection. An inspection of the time course of this effect revealed that 5.6 mg/kg methamphetamine, 30 mg/kg 3-FMC, and 30 mg/kg methylone showed the longest duration of action. The time courses of cocaine, MDPV, mephedrone, and 4-FMC were characterized by steady attenuation of the high level of initial activity over the course of the 90-min session. Methedrone produced the flattest time-response function and shortest duration of effects. When higher doses of all cathinones were examined in rotorod performance, 3-FMC and methylone produced decreases in locomotor coordination and balance, whereas 4-FMC, MDPV, mephedrone, and methedrone did not affect rotorod performance.

Consistent with the locomotor activation produced by synthetic cathinones, analysis of their effects on the overt behavior of mice in the FOB suggested that all compounds tested here produced significant increases in observational measures related to stimulant action, including hyperactivity, stimulation, and stereotyped head weaving and head circling. Except for mephedrone, all cathinones (and cocaine and methamphetamine) also increased circling. Interestingly, cathinone extracted from C. edulis has also been shown to increase stereotyped movements in rodents, including biting, licking, pawing, sniffing, and head twitches at high doses (al-Meshal et al., 1991; Banjaw et al., 2003; Banjaw et al., 2005; Banjaw et al., 2006; Kalix and Braenden, 1985; Zelger et al., 1980), suggesting that these behaviors are characteristic of this class of compounds in rodents. Additionally, other research reported cathinone-induced tremors at low doses, and seizures at high doses (Berardelli et al., 1980). In the present study, methylone produced tremors and convulsions at the highest dose examined (56 mg/kg). Occurrence of the other behaviors included in the FOB (i.e., ataxia, exploration, salivation, and compulsive movements) was more sporadic across the test compounds, suggesting that perhaps these synthetic cathinones are not homogenous in their pharmacological effects. The synthetic cathinone with the heaviest “behavioral burden” in the FOB was 3-FMC, which significantly increased most behaviors in the FOB at one or more doses. At doses above those at which it stimulated locomotor activity, 3-FMC also impaired performance on the rotorod, as is consistent with the increased ataxia that was observed in the FOB.

Finally, an effect that was observed in mice with some of the compounds, but has not typically been reported for humans, is excessive salivation. The compounds that produced this effect were methamphetamine, 3-FMC, methedrone and methylone. Previous research has shown that methylenedioxymethylamphetamine (MDMA) produces increased salivation in rats (Frith et al., 1987) and this increase is dose dependent (Spanos and Yamamoto, 1989). Interestingly, in humans methamphetamine has been associated with hyposalivation that may contribute to the development of “meth mouth” (i.e., extreme dental deterioration) in many regular users (Saini et al., 2005); however, this effect may be the result of chronic use versus acute exposure (as occurred in the present study). Although neural control of saliva secretion in humans is usually conceived of as a function of parasympathetic stimulation (e.g., muscarinic action), with accompanying inhibition of sympathetic stimulation, sympathetic stimulation does not inhibit secretion in rodents (Proctor and Carpenter, 2007). Hence, it is possible that methamphetamine, 3-FMC, methedrone and methylone may increase salivation through acute interaction with brain systems that modulate primarily autonomic responses such as salivation. While determination of the mechanism(s) for this effect is beyond the scope of this paper, the fact that it occurs with only some of the compounds suggests individual synthetic cathinones may not have identical neural targets.

Humans self-report preferring stimulant drugs with a rapid onset and shorter duration of action, such as cocaine, citing that the onset of effects is the most pleasurable effect of the drug, and the short duration of action allows repeated dosing and hence more frequent exposure to the onset of effects (Fischman, 1989). This preference for drugs with quick onsets and shorter durations of action suggests that drugs with this profile are more likely to be abused. Therefore, of the cathinone analogs studied here, MDPV, mephedrone, and 4-FMC are likely to be most favored because they caused large, rapid initial increases in locomotor activity which deteriorated throughout the session (Calabrese, 2008; Fischman, 1989; Wise and Bozarth, 1987), albeit stimulants with rapid onset and slow offset (such as methamphetamine) may also be abused.

Not surprisingly, investigation of the neural mechanisms of synthetic cathinones has focused on the effects of a subset of these compounds on monoamine neurotransmission. For example, MDPV inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine (Meltzer et al., 2006; Psychonaut, 2009), effects that are similar to those produced by cocaine (Matecka et al., 1996; Rothman et al., 2001; Spanagel and Weiss, 1999). Mephedrone and methylone release dopamine, norephinephrine, and serotonin (Baumann et al., 2012; Cozzi et al. 1999; Martinez-Clemente et al., 2012; Nagai et al., 2007; Winstock et al., 2010a), effects that overlap with those of amphetamine (Cozzi et al. 1999; Nagai et al., 2007; Rothman et al., 2001; Sulzer et al., 2005). The precise neural mechanisms of 3-FMC, 4-FMC, and methedrone remain unknown, but based upon their similar behavioral effects, are likely to resemble those of MDPV, mephedrone and methylone.

One factor to take into account when drawing conclusions from the present study is whether differences are related to distinct mechanisms of action or to the dose range chosen for testing. For the locomotor study, dose ranges for mephedrone were based on previous in vivo research (Angoa-Perez et al, 2012; Hadlock et al., 2011; Kehr et al., 2011); however, most of the other compounds had not yet been tested in vivo, making dose choice somewhat problematic. Doses for the rotorod/FOB study were based on the potency found for each cathinone in the locomotor test. Since different synthetic cathinones were studied over different dose ranges, some differences in effects shown by different cathinones may be attributable to the different doses assessed rather than different cathinones themselves. Only further examination of synthetic cathinones can confirm if the differences between effects of cathinones in the present study was due to dose or compound.

A second caveat regarding interpretation of the present results is the possibility that the first administration of a synthetic cathinone produced neurotoxic effects that altered responses to the second injection. The neurotoxicity of synthetic cathinones has been examined in a few studies, which collectively show mixed results. Two studies found that repeated administration of mephedrone to mice (Angoa-Perez et al., 2012) and rats (Baumann et al., 2012), and repeated administration of methylone to rats (Baumann et al., 2012) did not cause any decrement in cortical or striatal monoamine neurotransmitters (Baumann et al., 2012). In contrast, another study found that repeated administration of mephedrone caused serotonergic decrements in rats (Hadlock et al., 2011). Repeated administration of common drugs of abuse, methamphetamine and MDMA, to rodents has also been found to reliably cause neurotoxicity (Thomas et al., 2004; Baumann et al., 2012). While the possibility of carry-over neurotoxic effects from acute injection cannot be completely ruled out here, it is unlikely. In the studies where neurotoxicity has been observed (see above), eight administrations of methamphetamine over the course of two days, or three administrations of MDMA in one day has been required. Neurotoxicity after acute administration of cathinones has not been demonstrated, albeit this issue has not been investigated extensively for even the known cathinones and certainly not for novel synthetic cathinones. Similarly, the long term effects and duration of action of synthetic cathinones and their metabolites is unknown. Hence, the two-week window between the first and second administration of synthetic cathinones may not have been long enough for all effects to subside.

5. Conclusion

As bath salt manufacturers attempt to remain one step ahead of the legal system, it is likely that some of the other synthetic cathinones investigated here (3-FMC; 4-FMC; methedrone) are already contained in the bath salt formulations currently being sold. Other potential psychoactive components that are legal and may be found in bath salts in the future include 4-methylmethamphetamine (4-MMA), the β-deketo analog of mephedrone, and methylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (MBDB), an amphetamine analog which is very structurally similar to MDPV (Gibbons and Zloh, 2010). The present research on 3-FMC, 4-FMC, and methedrone indicate these synthetic cathinones appear to share major pharmacological properties with the ones that have been banned (mephedrone, MDPV, and methylone), suggesting that they may be just as harmful. In addition, however, the present results imply that individual synthetic cathinones may differ in their exact profile of behavioral effects.

Bath salts are emerging drugs of abuse that contain both legal and illegal cathinones.

Effects of synthetic cathinones found in bath salts were compared to cocaine and methamphetamine.

All cathinones produced typical stimulant-induced increases in locomotor activity

Some cathinones produced more behaviorally toxic effects than classic stimulants of abuse.

Individual synthetic cathinones differ in their profile of effects, and differ from known stimulants of abuse.

Acknowledgements

Research supported by RTI International internal research and development funds, as well as the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA 12970). The authors thank Antonio Landavazo and Timothy Lefever for technical assistance. Reprints may be obtained from the first author at jmarusich@rti.org or from any of the authors at RTI International, 3040 Cornwallis Rd, Research Triangle Pk, NC 27709.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACMD (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs) Consideration of the cathinones. 2010.

- CDC (Center for Disease Control) Emergency Department Visits After Use of a Drug Sold as “Bath Salts.”. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:624–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Meshal IA, Qureshi S, Ageel AM, Tariq M. The toxicity of Catha edulis (khat) in mice. J Subst Abuse. 1991;3:107–115. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Poison Control Centers Bath Salts Data. 2012. Updated January 5, 2012.

- Angoa-Pérez M, Kane MJ, Francescutti DM, Sykes KE, Shah MM, Mohammed AM, Thomas DM, Kuhn DM. Mephedrone, an Abused Psychoactive Component of “Bath Salts” and Methamphetamine Congener, Does not Cause Neurotoxicity to Dopamine Nerve Endings of the Striatum. J Neurochem. 2012;120:1097–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonowicz JL, Metzger AK, Ramanujam SL. Paranoid psychosis induced by consumption of methylenedioxypyrovalerone: two cases. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:640, e5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjaw MY, Fendt M, Schmidt WJ. Clozapine attenuates the locomotor sensitisation and the prepulse inhibition deficit induced by a repeated oral administration of Catha edulis extract and cathinone in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2005;160:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjaw MY, Mayerhofer A, Schmidt WJ. Anticataleptic activity of cathinone and MDMA (Ecstasy) upon acute and subchronic administration in rat. Synapse. 2003;49:232–238. doi: 10.1002/syn.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjaw MY, Miczek K, Schmidt WJ. Repeated Catha edulis oral administration enhances the baseline aggressive behavior in isolated rats. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:543–556. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Ayestas MA, Jr, Partilla JS, Sink JR, Shulgin AT, Daley PF, Brandt SD, Rothman RB, Ruoho AE, Cozzi NV. The Designer Methcathinone Analogs, Mephedrone and Methylone, are Substrates for Monoamine Transporters in Brain Tissue. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1192–1203. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli A, Capocaccia L, Pacitti C, Tancredi V, Quinteri F, Elmi AS. Behavioral and EEG effects induced by an amphetamine like substance (cathinone) in rats. Pharmacol Res Commun. 1980;12:959–964. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(80)80163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ. Addiction and dose response: the psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction reveals that hormetic dose responses are dominant. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2008;387:599–617. doi: 10.1080/10408440802026315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri A, Johnston MR, Brennan M, Davis S, Caldicott DGE. Chemical analysis of four capsules containing the controlled substance analogues 4-methylmethcathinone, 2-fluormethamphetamine, α- phthalimidopropiophenone and Nethylcathinone. Forens Sci Int. 2010;197:59. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi NV, Sievert MK, Shulgin AT, Jacob P, Ruoho AE. Inhibition of plasma membrane monoamine transporters by beta-ketoamphetamines. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;381:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEA (Drug Enforcement Agency) Synthetic Cathinones - DEA Request for Information. 2011. [7/28/11]. Posted 3/31/11.

- Eastwood N. Legal eye. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2010;10:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) EMCDDA and Europol step up information collection on mephedrone. 2010.

- Fischman MW. Relationship between self-reported drug effects and their reinforcing effects: Studies with stimulant drugs. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;92:211–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster MJ, Lal H. Estimating age-related changes in psychomotor function: influence of practice and of level of caloric intake in different genotypes. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00041-x. (1999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CH, Chang LW, Lattin DL, Walls RC, Hamm J, Doblin R. Toxicity of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in the dog and the rat. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1987;9:110–119. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(87)90158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons S, Zloh M. An analysis of the ‘legal high’ mephedrone. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4135–4139. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths P, Lopez D, Sedefov R, Gallegos A, Hughes B, Noor A, Royuela L. Khat use and monitoring drug use in Europe: The current situation and issues for the future. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock GC, Webb KM, McFadden LM, Chu PW, Ellis JD, Allen SC, Andrenyak DM, Vieira-Brock PL, German CL, Conrad KM, Hoonakker AJ, Gibb JW, Wilkins DG, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. 4-Methylmethcathinone (mephedrone): neuropharmacological effects of a designer stimulant of abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:530–536. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.184119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatav V, Mishra P, Kashaw S, Stables JP. CNS depressant and anticonvulsant activities of some novel 3-[5-substituted 1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-yl]-2-styryl quinazoline-4(3H)-ones. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:1945–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalix P. Cathinone, a natural amphetamine. Pharmacol Toxicol. 70:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalix P, Braenden O. Pharmacological aspects of the chewing of khat leaves. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;37:149–164. (1985) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L, Reynaud M. GHB and synthetic cathinones: clinical effects and potential consequences. Drug Test Anal. 2010;3:552–559. doi: 10.1002/dta.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr J, Ichinose F, Yoshitake S, Goiny M, Sievertsson T, Nyberg F, Yoshitake T. Mephedrone, compared to MDMA (ecstasy) and amphetamine, rapidly increases both dopamine and serotonin levels in nucleus accumbens of awake rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1949–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Clemente J, Escubedo E, Pubill D, Camarasa J. Interaction of mephedrone with dopamine and serotonin targets in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matecka D, Rothman RB, Radesca L, de Costa BR, Dersch CM, Partilla JS, Pert A, Glowa JR, Wojnicki FH, Rice KC. Development of Novel, Potent, and Selective Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors through Alteration of the Piperazine Ring of 1-[2-(Diphenylmethoxy)ethyl]- and 1-[2-[Bis(4-fluorophenyl)methoxy]ethyl]-4-(3-phenylpropyl)piperazines (GBR 12935 and GBR 12909). J Med Chem. 1996;39:4704–4716. doi: 10.1021/jm960305h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer PC, Butler D, Deschamps JR, Madras BK. 1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (Pyrovalerone) analogues: a promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1420–1432. doi: 10.1021/jm050797a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motbey CP, Hunt GE, Bowen MT, Artiss S, McGregor IS. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone, ‘meow’): acute behavioural effects and distribution of Fos expression in adolescent rats. Addict Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00384.x. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 21995495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai F, Nonaka R, Satoh Hisashi Kamimura K. “The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain”. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;559:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehek EA, Schechter MD, Yamamoto BK. Effects of cathinone and amphetamine on the neurochemistry of dopamine in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:1171–1176. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor GB, Carpenter GH. Regulation of salivary gland function by autonomic nerves. Auton Neurosci. 2007;133:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychonaut Research Web Mapping Project . MDPV report. Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London; London, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS. Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin. Synapse. 2001;39:32–41. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini TS, Edwards PC, Kimmes NS, Carroll LR, Shaner JW, Dowd FJ. Etiology of xerostomia and dental caries among methamphetamine abusers. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano F, Albanese A, Fergus S, Stair JL, Deluca P, Corazza O, Davey Z, Corkery J, Siemann H, Scherbaum N, Farre M, Torrens M, Demetrovics Z, Ghodse AH. Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone; ‘meow meow’): chemical, pharmacological and clinical issues. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Weiss F. The dopamine hypothesis of reward: past and current status. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos LJ, Yamamoto BK. Acute and subchronic effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine [(+/-)MDMA] on locomotion and serotonin syndrome behavior in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:835–840. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs” (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol. 2011;49:499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Branda EM, Kruschel CK. The effects of atypical antipsychotics and phencyclidine (PCP) on rotorod performance. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striebel JM, Pierre JM. Acute psychotic sequelae of “bath salts.”. Schizophr Res. 2011;113:259–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: A review. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Walker PD, Benjamins JA, Geddes TJ, Kuhn DM. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity in dopamine nerve endings of the striatum is associated with microglial activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Risk assessment forum. U.S. EPA; Washington, DC: 1998a. Guidelines for neurotoxicity risk assessment. 630/R-95/001F. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/raf/publications/guidelines-neurotoxicity-risk-assessment.htm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Health effects guidelines: Neurotoxicity screening battery. U.S. EPA; Washington, DC: 1998b. EPA 712-C-98-238. OPPTS 870.6200. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/ocspp/pubs/frs/publications/Test_Guidelines/series870.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Wagner GC. Motor impairments after methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:617–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Marsden J, Mitcheson L. What should be done about mephedrone? BJM. 2010;340:c1605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction. 2011;106:154–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987;94:469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfarth A, Weinmann W. Bioanalysis of new designer drugs. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:965–79. doi: 10.4155/bio.10.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelger JL, Schorno HX, Carlini EA. Behavioural effects of cathinone, an amine obtained from Catha edulis Forsk.: comparisons with amphetamine, norpseudoephedrine, apomorphine and nomifensine. Bull Narc. 1980;32:67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]