Abstract

Long before humans roamed the planet, porphyrins in blood were serving not only as indispensable oxygen carriers, but also as the bright red contrast agent that unmistakably indicates injury sites. They have proven valuable as whole body imaging modalities have emerged, with endogenous hemoglobin porphyrins being used for new approaches such as functional magnetic resonance imaging and photoacoustic imaging. With the capability for both near infrared fluorescence imaging and phototherapy, porphyrins were the first exogenous agents that were employed with intrinsic multimodal theranostic character. Porphyrins have been used as tumor-specific diagnostic fluorescence imaging agents since 1924, as positron emission agents since 1951, and as magnetic resonance (MR) contrast agents since 1987. Exogenous porphyrins remain in clinical use for photodynamic therapy. Because they can chelate a wide range of metals, exogenous porphyrins have demonstrated potential for use in radiotherapy and multimodal imaging modalities. Going forward, intrinsic porphyrin biocompatibility and multimodality will keep new applications of this class of molecules at the forefront of theranostic research.

Keywords: Porphyrins, theranostics

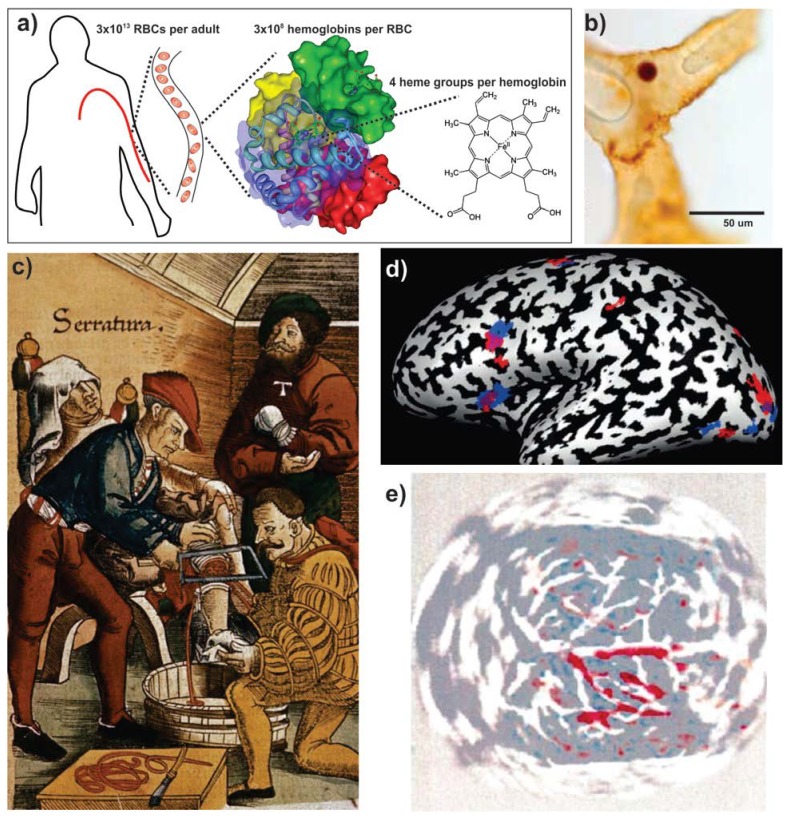

1. Hundreds of millions of years of theranostics

Porphyrins exist abundantly in plants, animals and rocks 1 and have even been found in lunar dust 2. They existed by the time the first chlorophyll-containing photosynthetic organisms appeared some 3 billion years ago to initiate the creation of a new atmosphere, rich with life-supporting oxygen 3. Our present ecosystem relies extensively on porphyrins for various vital roles ranging from photosynthesis to oxygen transport, in the form of chlorophyll and heme. Iron, which is chelated in the center of the heme group, may have been selected instead of another metal for evolutionary reasons, due to its abundance in the crust of earth 4. Hemoglobin and myoglobin are believed to have emerged more than 600 million years ago 5. Structurally, hemoglobin consists of four protein subunits, with each subunit associated with a heme group chelated with an iron atom in the center (Fig 1a) 6. Its evolution permitted animals to develop complex circulatory systems, which in turn permitted larger organism sizes and higher functions. Hemoglobin is packed into red blood cells (RBCs), which are the most abundant cells in blood and can be traced back to ancient times (for e.g., a probable 65 million year old dinosaur RBC is shown in Fig. 1b) 7. RBCs have a characteristic biconcave shape 7-8 µm in diameter and play a major role in human physiology 8. RBCs are produced at an astounding rate of approximately 2×106 per second and there are 2-3×1013 in circulation at any given moment in a human adult body. Oxygen delivery is mediated by the nearly 300 million hemoglobin molecules in each RBC, which comprise some 3 x 1022 total heme porphyrin group in the body 9 (Fig 1a). In addition, a wide range of other porphyrins is found in prosthetic groups within cells (e.g. cytochromes and vitamin B12).

Figure 1.

Endogenous porphyrins. a) Schematic organization of heme in the body 6,9. b) A possible heme-containing red blood cell identified in 65 million year old dinosaur tissue 7. c) Surgical illustration of an amputation from circa 1500 AD. Excessive bleeding can readily be observed due to the bright red heme to guide tourniquet application (Archives & Special Collections, Columbia University Health Sciences Library). d) BOLD MR imaging using heme oxygenation. In this case neural differences between English and Hebrew speech patterns are shown. Blue and red regions are involved in morphological processing in Hebrew and English, respectively and regions of overlap are shown in purple 22. e) Non-invasive, rat brain transcranial photoacoustic imaging following right-side whisker stimulation 26. Reproduced with permission from the publishers of corresponding references.

Hemoglobin was first isolated by Hunefeld in 1840 5,10 and its molecular structure was revealed over one hundred years later using X-ray crystallography 11. The first analytical applications using porphyrins originate much earlier, in the era of the first blood-bearing creatures. Heme has long been recognized as the red pigment of our blood, even if the molecular details were not known. Porphyrins in different forms can be found in many different colors. Among them, the bright red color of blood, visible under natural light, has been providing health guidance for millions of years already. For instance, an injury that causes bleeding can be detected by eye by both an injured animal and other parties who wish to provide assistance (or possibly prey on the injured). Fig 1c shows a 16th century painting of an amputation operation from one of the earliest recorded medical textbooks, illustrating how visual detection of blood has long provided optical feedback for guiding medical procedures. The evolutionary importance of heme is reflected in human responses to even the sight of the color red. Immersion in red rooms is associated with generating active and excited psychological states and it has been shown that some muscular responses are over 10 percent faster than normal in red light 12. Red stimulates tension and restlessness; physiologically, the sight of the color can even increase blood pressure, pulse and respiration 13. Thus, the intrinsic importance of heme as an indicator for bleeding is reflected in its role through human evolution to invoke response and reaction to avoid and deal with bleeding. Today, blood still maintains its theranostic legacy in millions of medical procedures performed each day as an endogenous and highly visible optical contrast agent.

In the past decades, technological advances in medical imaging have emerged concurrently and co-operatively with theranostic medicine 14. Heme serves as an important endogenous contrast agent in at least two imaging techniques; functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and photoacoustic tomography (PAT). Hemoglobin in the form of oxyhemoglobin carries molecular oxygen to cells for cellular respiration and following oxygen delivery, returns to the lungs in the form of deoxyhemoglobin. The iron chelated in the center of hemoglobin can change its valency between Fe2+ and Fe3+ to help enable precise oxygen delivery 15. The differences between oxy and deoxyhemoglobin can be detected by optical and MR methods.

Understanding neural activities via functional brain mapping is challenging. Fluctuating electrical signals on the scalp have been able to provide some information about electrical activity in the outer cortex of the brain, but cannot provide a deep or detailed three-dimensional volumetric map of brain activity. The birth of fMRI ushered in a new era in the study of the working brain and serves as a central focus in modern neuroimaging since it enables indirect measurement of metabolic activity and blood changes caused by neural activity. fMRI was developed on the basis of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). NMR, discovered in 1946, is based on the phenomenon of nuclear spin, resulting in resonance radiofrequency absorption in the presence of an extrinsic magnetic field 16. About 30 years later, MRI emerged based on tissue-specific differences in transverse and longitudinal relaxation rates among different tissues 17. The focus of fMRI, compared to the conventional MRI, is to investigate metabolic activities through its sensitivity to relative levels of oxygen in blood. This technique, which has been gaining much attention since 1991, offers an indirect interpretation of neural activity based on the changes of blood volume, blood flow and blood oxygenation (also collectively referred to as hemodynamic oxygenation) 18-20. It has been shown that when diamagnetic oxyhemoglobin releases its oxygen, the dexoyhemoglobin becomes paramagnetic, which influences the transverse relaxation rates of water proton spins in the immediate vicinity of vessels, resulting in the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast 21. When a certain area of brain is active, oxygen metabolic rate increases, but the blood flow increases as well so the overall outcome is the oxygen extraction fraction drops, leading to more oxygenated venous blood, ultimately resulting in locally increasing MR signals. Even when the brain is given only somewhat different tasks, for instance, using either English or Hebrew speech patterns, remarkably precise activation maps of the brain can be obtained by fMRI (Fig. 1d) 22.

PAT is an emerging and high resolution optical imaging technique based on the photoacoustic effect 23,24. When biological tissues absorb a pulse of optical energy, the acoustic transient pressure excited by thermoelastic expansion will produce ultrasonic waves, referred to as photoacoustic waves. These waves are detected by an ultrasonic transducer and converted into electric signals which are used to generate images 24,25. Photoacoustic imaging can be used to non-invasively obtain functional images based on differences in optical absorption between oxy- and deoxy hemoglobin contained in blood. Photoacoustic methods can provide information on hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation, indicating tumor angiogenesis, hypoxia or hypermetabolism, which are important parameters of cancer characterization. Meanwhile, based on the relation of neural activity and cerebral blood parameters (e.g. hemodynamics), PAT of cerebral activity can be obtained noninvasively and infer neural activity. As shown in Fig 1e, PAT can be used for functional imaging of cerebral hemodynamic changes induced by whisker stimulation in a rat 26. Also, increasing focus has been placed on clinical applications in humans. For example, it was shown that PAT can be used to obtain images of breast tumors 27 and subcutaneous microvasculature skin in humans 28. There still remains some challenges for applying PAT in the human brain due to the thickness of human skull 29. As imaging methods improve, fMRI and PAT will continue to be prominent functional imaging modalities based on oxy and deoxy heme.

2. The original exogenous agents for imaging and therapy

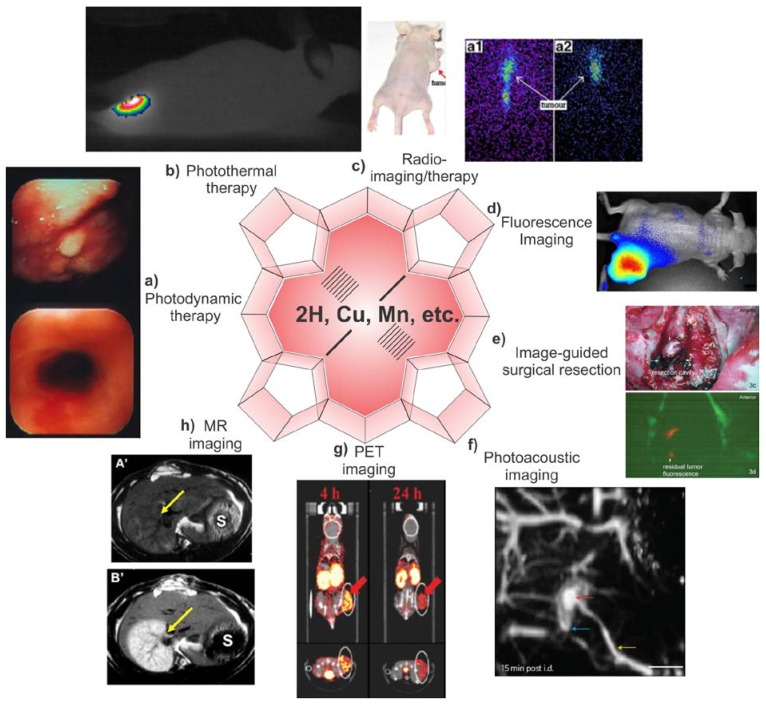

Endogenous porphyrins play a central and historic role in theranostic medicine, but exogenous porphyrins are also of considerable significance. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a clinical and minimally invasive method to treat cancers and other diseases. It involves three elements: a photosensitizer, light and oxygen. Porphyrin and porphyrin-related compounds are the most commonly used photosensitizers. After administration and delivery of a photosensitizer to a tumor site and upon light irradiation, it will generate reactive singlet oxygen (1O2), leading to cell death and tumor destruction 30-35. Fig. 2a shows the efficacy of PDT using hexyloxyethyl devinylpyropheophorbide-a (HPPH or Photochlor) in destroying esophageal cancer 36. PDT also has been clinically successful in treating other diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and acne 37,38. Singlet oxygen (1O2) has a small diffusion range less than the diameter of a cell, therefore restricting damage only to the treatment site 39. As a variant of PDT, photothermal therapy (PTT) was proposed as another method for cancer treatment using porphyrins at least as early as 1999 40,41. Generally, in the promotion of photothermal sensitized processes, photosensitized species can generate electronic excitation energy upon irradiation, leading to local temperature rises and to the destruction of cancer cells 42, even in the absence of oxygen 43. As shown in Fig 2b, when porphysomes (nanoparticles formed by the conjugation of porphyrin to a phospholipid) were administered to a tumor bearing mouse and irradiated by a 658 nm laser outputting 750 mW with a power density of 1.9 W/cm2 for 1 min, the tumor temperature rapidly increased to 60 ºC while the tumors in control experiment with PBS injected did not increase in temperature beyond 40 ºC 44. Light absorbing species can include metallic nanoparticles (e.g. Au, Ag) 45, cyanine dyes 46, azo-dyes 47, porphyrins 43,48, naphthalocyanines 41 and many others.

Figure 2.

Multimodal theranostic capabilities of exogenous porphyrins. a) Human esophageal cancer successfully treated with PDT 36. b) Photothermal image of a xenograft bearing mouse injected with porphysomes and then irradiated by laser for 1 min showing tumor temperature rapidly rising above 60 ºC 44. c) Radiotherapy: Melanoma imaging of 188Re-T3,4 CPP in tumor bearing mice. Scintigraphic images were collected at 8h (a1) and 24 h (a2), showing porphyrin potential in radiotherapy and imaging 85. d) Near infrared fluorescence imaging of porphysome activation in a KB xenograft bearing mouse 44. e) Fluorescence Guided Resection (FGR): the surgical cavity after white light resection of brain tumor in rabbit (top), fluorescence imaging of PpIX showing tumor margins. Additional FGR can improve the accuracy of resection 105. f) Photoacoustic image of rat lymphatics mapped following intradermal injection of porphysomes in rats 44. g) PET imaging showing clear delineation between the tumor and other tissues by PET was obtained at 4, 24 h after intravenous injection of a targeted 64Cu porphyrin 116. h) MR imaging: In the top precontrast T1 weighted image, the infarcted right liver lobe (arrow) was barely detected whereas 24 h after injection of Gadophrin-2 at 0.05 mmol/kg the infarcted liver lobe was strongly enhanced (bottom) 125. Reproduced with permission from the publishers of corresponding references.

In the early 1900s, a number of photosensitizers were investigated for treatments of certain cancers and skin diseases 49-51. Oscar Raab was perplexed by some inconsistent data that were generated during a heavy lightning storm; he started to wonder about the effect of light and discovered photodynamic reactions in the process 51-53. Oxygen was soon determined to be an important mediator for photosensitization and the term “photodynamic action” was coined in 1907 51,54,55. Hematoporphyrin, usually extracted from bovine blood, has been used since this time. This porphyrin was first isolated from dried blood in 1841 56,57; its fluorescence properties were observed in 1867 57,58 and its photobiological properties were studied in mice in 1911 57,59. When administered hematoporphyrin and irradiated with light, mice exhibited skin photosensitivity and phototoxicity. Around the same time, a German doctor boldly injected hematoporphyrin into himself and demonstrated how exogenous porphyrins were sunlight photosensitizers in humans 51,60. Another early and important discovery is that the concentration of tetratraphenylporphinesulfonate (TPPS) detected in tumors of rats was higher than that using hematoporphyrins, indicating better tumor localizing ability of TPPS 61. These pioneering works of PDT occurred mostly in Europe and were reported in non-English languages, but the rich history of PDT has been summarized by several comprehensive literature reviews 51,57,62.

Porphyrins, their derivatives or porphyrin-inducing drugs are by far the most commonly used photosensitizers in PDT. One milestone of PDT occurred when Diamond et al. reported favorable results of cancer treatment in rats in 1972, using crude hematoporphyrins as a photosensitizer combined with white light from fluorescent lamps 63. When rats bearing subcutaneous glioma cell tumors were intravenously injected with hematoporphyrin and irradiated by white light a day after injection, tumors showed dramatic shrinking. In control experiments, hematoporphyrin or light alone did not have anti-tumor effects. Building on this work, in 1975 Dougherty and coworkers from Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo demonstrated effective tumor destruction in more advanced animal models 64. Mice with mammary tumors were administered a hematoporphyrin derivative (HpD) and were exposed to red light. Half the transplanted mouse tumors were cured and favorable results were also obtained in the case of the rats bearing chemically-induced tumors given higher doses of HpD. At about the same time, it was found that mice with carcinomas transplanted from human bladder cancers were destroyed using HpD combined with local exposure to white light 65. Subsequently, phthalocyanines were introduced as photosensitizers, motivated by their typically higher absorption and longer wavelengths 66. There have been many porphyrin-related compounds that have had success or show promise for clinical or preclinical applications in PDT. Photofrin, a HpD, has been the most historic and commonly used photosensitizer, approved for the treatment of many cancers including lung, bladder, gastric and cervical. But hematoporphyrin derivatives have two disadvantages: 1) after administration, drugs are retained and taken up by skin so that patients are required to avoid bright light for long time; 2) the limited penetration depth around 630 nm limits the size of tumors treated effectively 67,68. Therefore, other porphyrin-based photosensitizers have been developed including Verteporfin, Photolon, and others. Other reviews comprehensively describe the clinical state of PDT and clinical trials using photosensitizers 33-35,38,51,69. Challenges like sunlight toxicity and lack of clinically proven targeting still exist, which have slowed the clinical application of PDT. In the method of vascular photosensitizer targeting, light placement can effectively destroy the vasculature and endothelium around the tumor, which is a promising clinical approach for the treatment of prostate cancer and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) 70,71. Recently, porphyrins and PDT have been widely employed to treat AMD. This medical condition is caused by choroidal neovascularization (CNV), leading to the damage of retina, loss of vision at macula, even to blindness eventually. Widespread clinical efforts have used verteporfin (trade name Visudyne) with PDT to prevent visual loss 72-75. PDT using porphyrins has also been applied to treat acne vulgaris, a common disease linked with the bacteria Propionibacterium acnes and the sebaceous glands 76. Conventionally, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory drugs and hormones were used topically or orally to fight against the pathogenetic factors 77,78. PDT has emerged as a highly effective alternative method in skin clinics 79,80. Most acne treatments induce protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) using aminolevulinic acid (ALA) or ALA derivatives and with appropriate light irradiation, PDT can cure inflammatory acne lesions with high efficacy 81,82.

Radiotherapy is another therapeutic modality for cancer treatment that can be mediated by porphyrins. Generally, aqueous radiolysis can generate free radicals which interact with biomolecules such as DNA, RNA, protein and membrane, resulting in the cell dysfunction and destruction 83. Due to their preferential uptake in tumors, some porphyrins have been used in targeted tumor radiotherapy when labeled with therapeutic radionuclides 84. For example, meso-tetrakis [3,4-bis(carboxymethyleneoxy)phenyl] porphyrin (T3,4CPP) was labeled with 188Re and used for targeted radiotherapy in mice 85. It was shown that in different tumor bearing mice 24 h postinjection, the tumor/muscle, tumor/blood, and tumor/liver ratio for 188Re-T3,4CPP was as high as 19, 9.6 and 4 ,respectively. Fig. 2c shows melanoma imaging of the 188Re porphyrin administered in tumor-bearing nude mice, showing the potential for radiotherapy and imaging. A review of 111In-tetrphenylporphyrins 86, 54Mn-HpD 87, 109Pb-Porphrins 88 and others summarizes radioporphyrin complexes comprehensively 89.

Not only do porphyrins have therapeutic functions, but they also emit fluorescence in the red or near infrared (NIR) and are useful for in vivo imaging. The first observation of porphyrin fluorescence from tumors was reported by Policard in 1924 57,90. The red fluorescence from hematoporphyrin was observed in a rat sarcoma during illumination with ultraviolet light but was mistakenly attributed to bacterial infection. Seven years later, similar results in breast carcinomas were observed and the possibility of bacteria was ruled out, confirming porphyrin imaging utility 91. In 1942, Auler and Banzer studied the localization of exogenously administered hematoporphyrins in tumors and found they favorably accumulated in tumor and lymph nodes in rats 92. Subsequent studies in the 1940s and 1950s further demonstrated that porphyrins exhibit affinity for neoplastic tissue 93-95. Thus, well over 50 years prior to the popularization of commercial fluorescence animal imaging systems 96, the fluorescence of porphyrins was observed to differentiate normal tissues and tumors in optical imaging studies. Porphyrin imaging can be used to predict the success or failure of photodynamic treatment 97,98 and also for fluorescence-guided surgical tumor resection 99. Fluorescence-guided surgery has emerged as an important research area especially for the treatment of the brain tumors. Generally, 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is a metabolic precursor inducing the synthesis of PpIX, which leads to the accumulation the fluorescence in malignant glioma tissues, thus providing identification for guided resection of tumors 100-104. Fig 2d and Fig. 2e show in vivo tumor fluorescence in mice 48 hours post injection of porphysomes 44 and image guided resection of brain tumors in rabbit (guided by the fluorescence of PpIX) 105, repectively. Exogenous porphyrins have also been widely used in other optical imaging techniques such as photoacoustic imaging. Fig. 2f shows the photoacoustic imaging of lymphatic mapping in rats after injection of 2.3 pmol porphysomes.

Porphyrins and related macrocycles, typically formed with a tetrapyrrole skeleton, can form metalloporphyrin complexes chelated with an incredibly diverse range of metals (e.g. Li, Be, Na, Mg, Al, K, Ca, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ga, Ge, Rb, Sr, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ag, Cd, In, Sn, Sb, Cs, Ba, Pt, Au, Hg, Tl, Pb, Bi, Th, Y, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Yb, and Lu) 89,106-108. Just as porphyrins led the way for fluorescence imaging and detection of tumors 90, in 1951, 64Cu-porphyrins were first used as positron emission radioisotopes for detection of brain injury and tumor 109. In this experiment, 64Cu phthalocyanine was synthesized successfully and doses of 100 mg/kg were given to rabbits, mice, guinea pigs, cats and dogs, then biodistribution and excretion were studied in rabbits. Although the positron emission tomography (PET) phenomenon has long been known, it has only recently been recognized as a valuable clinical and theranostic imaging modality in the last decades 110,111. 64Cu-porphyrins have been explored as promising probes 112,113 considering their favorable properties including excellent resistance to demetallation 109, minimal toxicity 114, the 12 hour half-life of 64Cu, and the pharmacokinetics of porphyrins 115. Recently, 64Cu was incorporated into targeted peptide consisting of pyropheophorbide-α, a peptide linker and folate (PPF). After 4 and 24h post-injection, preferred tumor/background ratio and clear delineation of tumor and other tissues was detectable by PET (Fig 2g). In this work, porphyrin accumulation in tumor at 4h was larger than that at 24h post-injection, which could be explained by the active targeting component of the PPF 116. 48V labeled pheophorbide has also been examined for PET imaging 117. In addition to PET, other diagnostic imaging modalities can be used combined such as computed tomography (CT), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), ultrasound, and MRI. For instance, PET images offer information on contrast targets with a high sensitivity, while CT and MRI stand out for their high resolutions. Hence, the combination of different imaging strategies (e.g. PET/CT, PET/MRI) compensate for disadvantages of each modality and obtain more reliable and detailed results with high spatial resolution and sensitivity 118,119.

Metalloporphyrins can be also used for enhancing MRI of tumors. MRI can offer information on tissue structure with high sensitivity based on physicochemical and physiological properties 120,121. However, MRI can have difficulty in distinguishing between neoplastic and normal tissues 122. Paramagnetic metals can be used as contrast agents that decrease these relaxation times, including the use of metal-chelated porphyrins 123,124. Paramagnetic metals (e.g. Mn2+, Gd3+) are chelated in metalloporphyrins and used as contrast agents which can cause a detectable relaxation in the surrounding water 125. In 1987, a water soluble metalloporphyrin, manganese (III) tetra-(4-sulfanatophenyl) porphyrin, Mn (III)TPPS4 was investigated as a contrast agent for MRI. Effective proton T1 and T2 relaxations induced by Mn(III)TPPS4 were obtained and good MRI enhancement using Mn(III)TPPS was observed in carcinomas, fibrosarcomas and lymphomas 126. Subsequently, metalloporphyrins of manganese tetrasodium-meso-tetra (4-sulfonatophenyl)-porphine (MnTPPS), manganese meso-tetra-4-pyridylporphine and gadolinium meso-tetra-4-pyridylporphine have been used as tumor specific MR imaging contrast agents in animal models 127. Paramagnetic metalloporphyrins show good chelate stability, low toxicity and high relaxivities. Gd 3+ has more unpaired electron spins and is more paramagnetic than Mn2+; Gd-chelated porphyrins such as Gadophrin-2 (bis-Gd-DTPA-mesoporphyrin), Gadophrin-3 (a copper inserted at the core to improve stability and safety), and texaphyrins have been explored as MRI contrast agents 128-130. MRI enhancement in necrotic tissue using Gadophrin-2 is clearly shown in Fig 2h. Compared to precontrast T1-weighted MRI, where an infarcted right liver lobe was almost undetectable, 24 hours after a 0.05 mmol/kg Gadophrin injection, the infarcted lobe was clearly demarcated 125. It is also worth mentioning that while some degree of tumor specific accumulation of porphyrins may be assumed, this is not always the case. For example, two metalloporphyrins, gadolinium mesoporphyrin (Gd-MP) and manganese tetraphenylporphyrin (Mn-TPP) did not prove to preferentially accumulate in viable tumors tissue of hepatomas 131.

3. Looking forward

Porphyrins have great potential to further advance the development of imaging and therapeutic approaches. Endogenous porphyrins will continue to prove their utility as improvements in instrumentation permit higher spatial and temporal resolution for techniques such as fMRI and photoacoustic imaging. Exogenous porphyrins have seen intensive activity in recent decades, resulting in many clinical approvals (e.g. Photofrin, Photolon, Visudyne, Foscan). Some novel porphyrins may continue to take on altered forms that enhance functionality, such as the development of photosensitizers with long wavelength absorptions to increase the penetration depth of light 36,132. Another strategy is the development of activatable photosensitizers to achieve local activation and minimize damage to adjacent tissues for PDT 38,133-135. New porphyrin nanocarriers have been explored, including polymers, micelles, dendrimers, liposomes, along with targeting strategies to better deliver the cargo 136,137.

Polymers are good carriers for porphyrin or phthalocyanine delivery. For instance, tetrakis (meso-hydroxyphenyl) porphrin (mTHPP) was formulated into polymeric micelles made of poly-(ethylene glycol)-co-poy (D, L-Lactic acid) (PEG-PLA) via a simple solvent evaporation method resulting in high loading efficiency (85%) and desirable micelle size (~30 nm) 138. Dendrimers have gained much attention in biomedical applications 139. Dendritic porphyrins (consisting of a focal porphyrin surrounded by poly benzyl ether dendrons) have been created and demonstrated to selectively accumulate in choroidal neovascularization (CNV) lesions 140. Liposomes are another commonly explored material for porphyrin delivery 141. One example is Visudyne, a health regulatory agency approved liposomal formulation of veteporfin 71. Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) liposomes have been used to encapsulate Photofrin in order to enhance photodynamic effect on tumors 142. While the enhanced permeability and retention effect enables nanoparticles to accumulate in tumor passively, active targeting strategy studies have also attracted much attention to improve specificity. Various targeting agents, showing affinity for a marker that is overexpressed on tumor cells, have been explored for targeting porphyrins, such as antibodies, aptamers, folate, growth factors, transferrin, and lipoproteins 143-147. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that some new carriers with triggered release mechanisms also hold potential for controlled porphyrin delivery, based on changes in temperature, pH, or light, leading to the carrier breakdown and local drug release 141,148-150. There are also new experimental emerging areas that feature quite different approaches to porphyrin theranostics. Among them, the porphysome is a recent discovery of an organic nanoparticle formed by the conjugation of porphyrin to a phospholipid 44. These nanovesicles exhibited large and tunable extinction coefficients and other unique nanoscale biophotonic properties for multimodal therapeutic applications. Porphysomes are also one of the first nanoparticles exhibiting enzymatic biodegradation in vivo 151.

In summary, porphyrins have existed universally since prehistoric times and have contributed, have evolved in step with life as we know it for billions of years, and continue to be prominent in biological, chemical and medical fields. Porphyrins facilitate optical and magnetic detection in the red heme in blood, serving as a natural and excellent theranostic agent. Exogenous porphyrins have also played indispensable and defining roles in modern theranostics, with new agents enabling multimodal imaging and multimodal therapy. With concerted research efforts, porphyrins will continue to add new chapters to their theranostic legacy into the coming decades and beyond.

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible by University at Buffalo startup funding.

References

- 1.Meinschein WG, Barghoorn ES, Schopf JW. Biological remnants in a precambrian sediment. Science. 1964;145:262–3. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3629.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson GW, Peterson E, Kvenvold KA, Bunnenbe E, Halpern B, Ponnampe C. Search for prophyrins in lunar dust. Science. 1970;167:763–5. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3918.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barghoorn ES. The oldest fossils. Sci Amer. 1971;224:30–42. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0571-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canham GWR. Porphyrins and evolutions. Canadian Chemical Education. 1972;8:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerkandl E. The evolution of hemoglobin. Sci Amer. 1965;212:110–8. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0565-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fermi G, Perutz MF, Shaanan B, Fourme R. The crystal structure of human deoxyhaemoglobin at 1.74 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1984;175:159–74. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweitzer MH, Wittmeyer JL, Horner JR Toporski, JK. Soft-tissue vessels and cellular preservation in tyrannosaurus rex. Science. 2005;307:1952–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1108397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierigè F, Serafini S, Rossi L, Magnani M. Cell-based drug delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:286–95. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller B.S, Kipps T.J. Williams' Hematology; 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1995. Examination of the blood. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunefeld F. L. Die chemismus in der thierischen organization. Brockhaus: Leipzig; 1840. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perutz MF, Rossmann MG, Cullis AF, Muirhead H, Will G, North ACT. Structure of hemoglobin: A three-dimensional fourier synthesis at 5.5-Å. resolution, obtained by X-ray analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–22. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birren F. Color psychology and color therapy; a factual study of the influence of color on human life. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birren Faber. Color & human response : aspects of light and color bearing on the reactions of living things and the welfare of human beings. New York : Van Nostrand Reinhold Co; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelkar SS, Reineke TM. Theranostics: Combining Imaging and Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:1879–903. doi: 10.1021/bc200151q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vannotti A. Porphyrins: their biological and chemical importance. London: Hilger & Watts; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell EM, Torrey HC, Pound RV. Resonance absorption by nuclear magnetic moments in a solid. Phys Rev. 1946;69:37–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buxton RB. Introduction to Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Principles and Techniques; 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belliveau J, Kennedy D, Mckinstry R, Buchbinder B, Weisskoff R, Cohen M, Vevea J, Brady T, Rosen B. Functional mapping of the human visual-cortex by magnetic resonance imaging. Science. 1991;254:716–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1948051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, Goldberg IE, Weisskoff RM, Poncelet BP, Kennedy DN, Hoppel BE, Cohen MS, Turner R. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5675–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa S, Tank DW, Menon R, Ellermann JM, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ugurbil K. Intrinsic signal changes accompanying sensory stimulation: functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5951–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa S, Lee T-M, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bick AS, Goelman G, Frost R. Hebrew brain vs. English brain: language modulates the way it is processed. J Cognitive Neurosci. 2010;23:2280–90. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim C, Favazza C, Wang LV. In vivo photoacoustic tomography of chemicals: high-resolution functional and molecular optical imaging at new depths. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2756–82. doi: 10.1021/cr900266s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu M, Wang LV. Photoacoustic imaging in biomedicine. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:041101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang LV. Prospects of photoacoustic tomography. Med Phys. 2008;35:5758–67. doi: 10.1118/1.3013698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Pang Y, Ku G, Xie X, Stoica G, Wang LV. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21:803–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ermilov SA, Khamapirad T, Conjusteau A, Leonard MH, Lacewell R, Mehta K, Miller T, Oraevsky AA. Laser optoacoustic imaging system for detection of breast cancer. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:024007. doi: 10.1117/1.3086616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Stoica G, Wang LV. Functional photoacoustic microscopy for high-resolution and noninvasive in vivo imaging. Nature Biotechnology. 2006;24:848–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography and sensing in biomedicine. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:R59–R97. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/19/R01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oleinick NL, Morris RL, Belichenko I. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: what, where, why, and how. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:1–21. doi: 10.1039/b108586g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessel D. Delivery of photosensitizing agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J. et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:250–81. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connor AE, Gallagher WM, Byrne AT. Porphyrin and nonporphyrin photosensitizers in oncology: preclinical and clinical advances in photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85:1053–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown SB, Brown EA, Walker I. The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandey RK, Goswami LN, Chen Y, Gryshuk A, Missert JR, Oseroff A, Dougherty TJ. Nature: A rich source for developing multifunctional agents. Tumor-imaging and photodynamic therapy. Laser Surg Med. 2006;38:445–67. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R. The porphyrin handbook. San Diego : Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovell JF, Liu TWB, Chen J, Zheng G. Activatable photosensitizers for imaging and therapy. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2839–57. doi: 10.1021/cr900236h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moan J. On the diffusion length of singlet oxygen in cells and tissues. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1990;6:343–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soncin M, Busetti A, Fusi F, Jori G, Rodgers MAJ. Irradiation of amelanotic melanoma cells with 532 nm high peak power pulsed laser radiation in the presence of the photothermal sensitizer Cu(II)-hematoporphyrin: a new approach to cell photoinactivation. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;69:708–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busetti A, Soncin M, Reddi E, Rodgers MAJ, Kenney ME, Jori G. Photothermal sensitization of amelanotic melanoma cells by Ni(II)-octabutoxy-naphthalocyanine. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1999;53:103–9. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(99)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camerin M, Rello S, Villanueva A, Ping X, Kenney ME, Rodgers MAJ, Jori G. Photothermal sensitisation as a novel therapeutic approach for tumours: Studies at the cellular and animal level. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Camerin M, Rodgers MAJ, Kenney ME, Jori G. Photothermal sensitisation: evidence for the lack of oxygen effect on the photosensitising activity. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2005;4:251–3. doi: 10.1039/b416418k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, Chan WCW, Cao W, Wang LV, Zheng G. Porphysome nanovesicles generated by porphyrin bilayers for use as multimodal biophotonic contrast agents. Nature Materials. 2011;10:324–32. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lal S, Clare SE, Halas NJ. Nanoshell-enabled photothermal cancer therapy: impending clinical impact. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1842–51. doi: 10.1021/ar800150g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen WR, Adams RL, Bartels KE, Nordquist RE. Chromophore-enhanced in vivo tumor cell destruction using an 808-nm diode laser. Cancer Lett. 1995;94:125–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03837-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isak SJ, Eyring EM, Spikes JD, Meekins PA. Direct blue dye solutions: photo properties. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2000;134:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazzaglia A, Trapani M, Micali N, Scolaro LM, Parisi T, Sciortino MT. Investigation of amphiphilic cyclodextrins encapsulating gold colloids and porphyrins for combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy on tumor HeLa cells. J Biotechnol. 2010;150:S192–S192. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tappeiner HV, Jesionek A. Therapeutische versuche mit fluorescierenden stoffen. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1903;47:2042–4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jesionek A, Tappeiner HV. Zur behandlung der hautcarcinome mit fluorescierenden stoffen. Archiv fur klinische Medizin. 1905;82:223. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moan J, Peng Q. An outline of the hundred-year history of PDT. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tappeiner HV. Ueber die Wirkung fluorescierenden stoffe auf Infusionrien nach versuchen Von O. Raab. Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1900;47:5. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raab O. Ueber die wirkung fluorescierenden stoffe auf infusorien. Zeitschrift fur Biologie. 1900;39:524–46. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tappeiner HV, Jodlbauer A. Uber die wirkung der photodynamischen (fluorescierenden) stoffe auf protozoen und enzyme. Deutsches Archiv fur klinische Medizin. 1904;80:327–487. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tappeiner HV, Jodlbauer A. Die sensibilisierende wirkung fluorescierender substanzer. untersuchungen uber die photodynamische erscheinung. FCW Vogel Leizig. 1907.

- 56.Scherer H. Chemisch-physiologische untersuchungen. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmazie. 1841;40:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ackroyd R, Kelty C, Brown N, Reed M. The history of photodetection and photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:656–69. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0656:thopap>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thudichum JL. Tenth report of the medical office of the privy council. London: HM Stationary Office; 1867. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hausmann W. Die sensibilisierende wirkung des hematoporphyrins. Biochemische Zeitschrift. 1911;30:276–316. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meyer-Betz F. Untersuchungen uder die Biologische (photodynamische) wirkung des hamatoporphyrins und anderer derivative des blu- und galenfarbstoffs. Deutsches Archiv fur klinische Medizin. 1913;112:476–503. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winkelman J. The distribution of Tetraphenylporphinesulfonate in the tumor-bearing rat. Cancer Res. 1962;22:589–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daniell M. D, Hill JS. A history of photodynamic therapy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:340–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diamond I, Jaenicke R, Wilson CB, Mcdonagh AF, Nielsen S, Granelli SG. Photodynamic therapy of malignant tumors. Lancet. 1972;2:1175–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dougherty TJ, Gb Grindey, Fiel R, Weishaupt KR, Boyle DG. Photoradiation therapy. II. Cure of animal tumors with hematoporphyrin and light. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:115–21. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelly JF, Snell ME, Berenbaum M. Photodynamic destruction of human bladder carcinomas. Brit J Cancer. 1975;31:237–44. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1975.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benhur E, Rosenthal I. Photosensitized inactivation of Chinese hamster cells by phthalocyanines. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;42:129–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1985.tb01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phillips D. Chemical mechanisms in photodynamic therapy with phthalocyanines. Prog React Kinet. 1997;22:175–300. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wohrle D, Hirth A, Bogdahn-Rai T, Schnurpfeil G, Shopova M. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: second and third generations of photosensitizers. Russ Chem Bull. 1998;47:807–16. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharman WM, Allen CM, Van Lier JE. Photodynamic therapeutics: basic principles and clinical applications. Drug Discov Today. 1999;4:507–17. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trachtenberg J, Bogaards A, Weersink RA, Haider MA, Evans A, McCluskey SA, Scherz A, Gertner MR, Yue C, Appu S, Aprikian A, Savard J. et al. Vascular targeted photodynamic therapy with Palladium-bacteriopheophorbide photosensitizer for recurrent prostate cancer following definitive radiation therapy: assessment of safety and treatment response. J Urol. 2007;178:1974–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Hasan T. Mechanisms of action of photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:195–214. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bressler NM. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: two-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials-tap report 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:198–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bressler NM, Arnold J, Benchaboune M, Blumenkranz MS, Fish GE, Gragoudas ES, Lewis H, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Slakter JS, Bressler SB, Manos K, Hao Y. et al. Verteporfin therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in patients with age-related macular degeneration - Additional information regarding baseline lesion composition's impact on vision outcomes-TAP report No. 3. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1443–54. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.11.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bressler NM. Verteporfin therapy for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration - Three-year results of an open-label extension of 2 randomized clinical trials - TAP report No. 5. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1307–14. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferris F, Fine S, Hyman L. Age-related macular degeneration and blindness due to neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1640–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040031330019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy: a new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:436–50. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.James WD. Acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1463–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp033487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Katsambas AD, Stefanaki C, Cunliffe WJ. Guidelines for treating acne. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gold MH. Acne and PDT: new techniques with lasers and light sources. Lasers Med Sci. 2007;22:67–72. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0420-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ross EV. Optical treatments for acne. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:253–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riddle CC, Terrell SN, Menser MB, Aires DJ, Schweiger ES. A review of photodynamic therapy (PDT) for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:1010–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hædersdal M, Togsverd-Bo K, Wulf HC. Evidence-based review of lasers, light sources and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2008;22:267–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nair CKK, Parida DK, Nomura T. Radioprotectors in radiotherapy. J Radiat Res. 2001;42:21–37. doi: 10.1269/jrr.42.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Das T, Chakraborty S, Sarma HD, Banerjee S. A novel [Pd-109] palladium labeled porphyrin for possible use in targeted radiotherapy. Radiochim Acta. 2008;96:427–33. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jia Z, Deng H, Pu M, Luo S. Rhenium-188 labelled meso-tetrakis[3,4-bis(carboxymethyleneoxy)phenyl] porphyrin for targeted radiotherapy: preliminary biological evaluation in mice. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:734–42. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vaum R, Heindel N, Burns H, Emrich J, Foster N. Synthesis and evaluation of an in-111-labeled porphyrin for lymph-node imaging. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71:1223–6. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600711110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crone-Escanye MC, Anghileri LJ, Robert J. In vivo distribution of 54Mn-hematoporphyrin derivative in tumor bearing mice. J Nucl Med Allied Sci. 1988;32:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hambright P, Fawwaz R, Valk P, McRae J, Bearden AJ. The distribution of various water soluble radioactive metalloporphyrins in tumor bearing mice. Bioinorg Chem. 1975;5:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3061(00)80224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ali H, van Lier JE. Metal complexes as photo- and radiosensitizers. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2379–450. doi: 10.1021/cr980439y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Policard A. Etude sur les aspects offerts par des tumeurs experimentales examinees a la lumiere de Wood. C R Soc Biol. 1924;91:1423–8. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Korbler J. Untersuchung von krebsgewebe im fluoreszenzerregenden licht. Strahlentherapie. 1931;41:510–8. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Auler H, Banzer G. Untersuchungen uber die rolle der porphyrine bei geschwulstkranken menschen und tieren. Zeitschrift fur Krebsforschung. 1942;53:65–8. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Figge FHJ, Weiland GS, Manganiello LOJ. Cancer detection and therapy: affinity of neoplastic, embryonic and traumatised tissues for porphyrins and metallo-porphyrins. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1948;68:640–1. doi: 10.3181/00379727-68-16580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Manganiello LOJ, Figge FHJ. Cancer detection and therapy 11: Methods of preparation and biological effects of metallo-porphyrins. Bull Sch Med Univ Maryland. 1951;36:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rasmussen TDS, Ward GE, Figge FHJ. Fluorescenceof human lymphatic and cancer tissues following high doses of intravenous hematoporphyrin. Cancer. 1955;8:78–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1955)8:1<78::aid-cncr2820080109>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leblond F, Davis SC, Valdés PA, Pogue BW. Pre-clinical whole-body fluorescence imaging: Review of instruments, methods and applications. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2010;98:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Josefsen LB, Boyle RW. Photodynamic therapy and the development of metal-based photosensitisers. Met Based Drugs. 2008;2008:276109. doi: 10.1155/2008/276109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilson BC, Patterson MS. The physics, biophysics and technology of photodynamic therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:R61–R109. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/9/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blake E, Allen J, Curnow A. An In vitro comparison of the effects of the iron-chelating agents, CP94 and dexrazoxane, on protoporphyrin IX accumulation for photodynamic therapy and/or fluorescence guided resection. Photochem and Photobiol. 2011;87:1419–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stummer W, Novotny A, Stepp H, Goetz C, Bise K, Reulen HJ. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrins: a prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:1003–13. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen H-J. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pichlmeier U, Bink A, Schackert G, Stummer W. Resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: An RTOG recursive partitioning analysis of ALA study patients. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:1025–34. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Valdés PA, Fan X, Ji S, Harris BT, Paulsen KD, Roberts DW. Estimation of brain deformation for volumetric image updating in protoporphyrin IX fluorescence-guided resection. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2010;88:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000258143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Valdés PA, Leblond F, Kim A, Harris BT, Wilson BC, Fan X, Tosteson TD, Hartov A, Ji S, Erkmen K, Simmons NE, Paulsen KD. et al. Quantitative fluorescence in intracranial tumor: implications for ALA-induced PpIX as an intraoperative biomarker. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:11–7. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.JNS101451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bogaards A, Varma A, Collens SP, Lin A, Giles A, Yang VXD, Bilbao JM, Lilge LD, Muller PJ, Wilson BC. Increased brain tumor resection using fluorescence image guidance in a preclinical model. Laser Surg Med. 2004;35:181–90. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Biesaga M, Pyrzyńska K, Trojanowicz M. Porphyrins in analytical chemistry. A review. Talanta. 2000;51:209–24. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(99)00291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Beletskaya I, Tyurin VS, Tsivadze AY, Guilard R, Stern C. Supramolecular chemistry of metalloporphyrins. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1659–713. doi: 10.1021/cr800247a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hambright P. The coordination chemistry of metalloporphyrins. Coord Chem Rev. 1971;6:247–68. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wrenn FR, Myron L. Good, Handler P. The use of positron-emitting radioisotopes for the localization of brain tumors. Science. 1951;113:525–7. doi: 10.1126/science.113.2940.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sörensen J. How does the patient benefit from clinical PET? Theranostics. 2012;2:427–36. doi: 10.7150/thno.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yaghoubi SS. Positron emission tomography reporter genes and reporter probes: gene and cell therapy applications. Theranostics. 2012;2:374–91. doi: 10.7150/thno.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wilson B C, Firnau G, Jeeves WP, Brwon KL, Burns-McCormick DM. Chromatographic analysis and tissue distribution of radiocopper-lablled haematoporphyrin derivatives. Lasers Med Sci. 1998;3:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Soucy-Faulkner A. et al. Copper-64 labelled sulfophthalocyanines for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in tumor-bearing rats. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2008;12:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bases R, Brodie SS, Rubenfeld S. Attempts at tumor localization using Cu 64-labeled copper porphyrins. Cancer. 1958;11:259–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195803/04)11:2<259::aid-cncr2820110206>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Firnau G, Wilson B C, Jeeves WP. 64Cu labelling of hematoporphyrin derivative for non-invasive in-vivo measurements of tumour uptake. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;170:629–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shi J. et al. Transforming a targeted porphyrin theranostic agent into a PET imaging probe for cancer. Theranostics. 2011;1:363–70. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iwai K, Kimura S, Ido T, Iwata R. Tumor uptake of [48V]Vanadyl-chlorine e6Na as a tumor-imaging agent in tumor-bearing mice. Nucl Med Biol. 1990;17:775–80. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(90)90025-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee D-E, Koo H, Sun I-C, Ryu JH, Kim K, Kwon IC. Multifunctional nanoparticles for multimodal imaging and theragnosis. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2656–72. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Louie A. Multimodality imaging probes: design and challenges. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3146–95. doi: 10.1021/cr9003538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Morgan CJ, Hendee WR. Introduction to magnetic resonance imaging. Denver: Multi-Media Publishing; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Braunschweiger PG, Schiffer LM, Furmanski P. 1H-NMR relaxation times and water compartmentalization in experimental tumor models. Magn Reson Imaging. 1986;4:335–42. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(86)91043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bottomley PA, Hardy CJ, Argersinger RE, Allen-Moore G. A review of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in pathology: Are T1 and T2 diagnostic? Med Phys. 1987;14:1–37. doi: 10.1118/1.596111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Manabe Y, Longley C, Furmanski P. High-level conjugation of chelating agents onto immunoglobulins: use of an intermediary poly(L-lysine)-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;883:460–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chen C, Cohen JS, Myers CE, Sohn M. Paramagnetic metalloporphyrins as potential contrast agents in NMR imaging. FEBS Lett. 1984;168:70–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ni Y. Metalloporphyrins and functional analogues as MRI contrast agents. Curr Med Imag Rev. 2008;4:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ogan M, Revel D, Brasch R. Metalloporphyrin contrast enhancement of tumors in magnetic-resonance-imaging - a study of human carcinoma, lymphoma, and fibrosarcoma in mice. Invest Radiol. 1987;22:822–8. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Furmanski P, Longley C. Metalloporphyrin enhancement of magnetic resonance imaging of human tumor xenografts in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4604–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Young SW, Qing F, Harriman A, Sessler JL, Dow WC, Mody TD, Hemmi GW, Hao YP, Miller RA. Gadolinium(III) texaphyrin: A tumor selective radiation sensitizer that is detectable by MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ni Y, Pislaru C, Bosmans H, Pislaru S, Miao Y, Bogaert J, Dymarkowski S, Yu J, Semmler W, Van de Werf F, Baert AL, Marchal G. Intracoronary delivery of Gd-DTPA and Gadophrin-2 for determination of myocardial viability with MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:876–83. doi: 10.1007/s003300000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Barkhausen J, Ebert W, Debatin JF, Weinmann HJ. Imaging of myocardial infarction: Comparison of magnevist and gadophrin-3 in rabbits. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1392–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ni Y, Marchal G, Jie Y, Lukito G, Petré C, Wevers M, Baert AL, Ebert W, Hilger C-S, Maier F-K, Semmler W. Localization of metalloporphyrin-induced “specific” enhancement in experimental liver tumors: Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging, microangiographic, and histologic findings. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:687–99. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(05)80437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wilson BC, Jeeves WP, Lowe DM, Adam G. Light propagation in animal tissues in the wavelength range 375-825 nanometers. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;170:115–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zheng G, Chen J, Stefflova K, Jarvi M, Li H, Wilson BC. Photodynamic molecular beacon as an activatable photosensitizer based on protease-controlled singlet oxygen quenching and activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8989–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611142104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zheng G, Graham A, Shibata M, Missert JR, Oseroff AR, Dougherty TJ, Pandey RK. Synthesis of β-galactose-conjugated chlorins derived by enyne metathesis as galectin-specific photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8709–16. doi: 10.1021/jo0105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lovell JF, Chan MW, Qi Q, Chen J, Zheng G. Porphyrin FRET acceptors for apoptosis induction and monitoring. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18580–2. doi: 10.1021/ja2083569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2:751–60. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ali I. et al. Advances in nano drugs for cancer chemotherapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:135–46. doi: 10.2174/156800911794328493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cohen EM, Ding H, Kessinger CW, Khemtong C, Gao J, Sumer BD. Polymeric micelle nanoparticles for photodynamic treatment of head and neck cancer cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nishiyama N, Jang W-D, Kataoka K. Supramolecular nanocarriers integrated with dendrimers encapsulating photosensitizers for effective photodynamic therapy and photochemical gene delivery. New J Chem. 2007;31:1074–82. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ideta R, Tasaka F, Jang W-D, Nishiyama N, Zhang G-D, Harada A, Yanagi Y, Tamaki Y, Aida T, Kataoka K. Nanotechnology-based photodynamic therapy for neovascular disease using a supramolecular nanocarrier loaded with a dendritic photosensitizer. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2426–31. doi: 10.1021/nl051679d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Derycke ASL, de Witte PAM. Liposomes for photodynamic therapy. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jiang F, Lilge L, Grenier J, Li Y, Wilson MD, Chopp M. Photodynamic therapy of U87 human glioma in nude rat using liposome-delivered photofrin. Laser Surg Med. 1998;22:74–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:2<74::aid-lsm2>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Derycke ASL, Kamuhabwa A, Gijsens A, Roskams T, De Vos D, Kasran A, Huwyler J, Missiaen L, de Witte P a. M. Transferrin-conjugated liposome targeting of photosensitizer AlPcS4 to rat bladder carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1620–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gupta S, Chaudhury N, Muralidhar K, Dwarakanath B, Mishra A, Jain V. In vitro and in vivo targeted delivery of photosensitizers to the tumor cells for enhanced photodynamic effects. J Can Res Ther. 2011;7:314–24. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.87035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gijsens A, Missiaen L, Merlevede W, de Witte P. Epidermal growth factor-mediated targeting of chlorin e6 selectively potentiates its photodynamic activity. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Morgan J, Lottman H, Abbou C, Chopin D. Comparison of direct and liposomal antibody conjugates of sulfonated Aluminum phthalocyanines for selective photoimmunotherapy of human bladder-carcinoma. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60:486–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shieh Y-A, Yang S-J, Wei M-F, Shieh M-J. Aptamer-based tumor-targeted drug delivery for photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1433–42. doi: 10.1021/nn901374b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ricchelli F, Gobbo S, Jori G, Salet C, Moreno G. Temperature-induced changes in fluorescence properties as a probe of porphyrin microenvironment in lipid-membranes 2. The partition of hematoporphyrin and protoporphyrin in mitochondria. Eur J Biochem. 1995;233:165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.165_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Anderson VC, Thompson DH. Triggered release of hydrophilic agents from plasmalogen liposomes using visible light or acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1109:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90183-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lovell JF, Jin H, Ng KK, Zheng G. Programmed nanoparticle aggregation using molecular beacons. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:7917–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, MacDonald TD, Cao W, Zheng G. Enzymatic regioselection for the synthesis and biodegradation of porphysome nanovesicles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2429–33. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]