Abstract

Past exposure to atomic bomb (A-bomb) radiation has exerted various long-lasting deleterious effects on the health of survivors. Some of these effects are seen even after >60 yr. In this study, we evaluated the subclinical inflammatory status of 442 A-bomb survivors, in terms of 8 inflammation-related cytokines or markers, comprised of plasma levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-4, IL-10, and immunoglobulins, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The effects of past radiation exposure and natural aging on these markers were individually assessed and compared. Next, to assess the biologically significant relationship between inflammation and radiation exposure or aging, which was masked by the interrelationship of those cytokines/markers, we used multivariate statistical analyses and evaluated the systemic markers of inflammation as scores being calculated by linear combinations of selected cytokines and markers. Our results indicate that a linear combination of ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR generated a score that was the most indicative of inflammation and revealed clear dependences on radiation dose and aging that were found to be statistically significant. The results suggest that collectively, radiation exposure, in conjunction with natural aging, may enhance the persistent inflammatory status of A-bomb survivors.—Hayashi, T., Morishita, Y., Khattree, R., Misumi, M., Sasaki, K., Hayashi, I., Yoshida, K., Kajimura, J., Kyoizumi, S., Imai, K., Kusunoki, Y., Nakachi, K. Evaluation of systemic markers of inflammation in atomic-bomb survivors with special reference to radiation and age effects.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, cytokines, immunosenescence

That atomic bomb (A-bomb) survivors continue to suffer from increased risks of selected cancers and other diseases was a principal finding of the Life Span Study in A-bomb survivors, which commenced in 1950 (1). These late effects pose serious, as yet unanswered, questions about the mechanisms underlying the observation. The list of diseases that reveal radiation-associated increased risks includes many inflammation-associated diseases, such as various cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and stroke (2–6). Recent studies have demonstrated that a great number of plasma cytokines are highly influenced by aging, and that persistently elevated levels of plasma inflammatory cytokines are sometimes associated with chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and Alzheimer's disease (7–10). Cytokines are involved in the regulation of inflammation and immunity, and they play a key role in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases and immunological disorders (11). Inflammation is characterized by a local reaction that may be followed by activation of a systemic acute-phase reaction (12). Interleukin (IL)-6, a key cytokine in inflammatory responses, induces the synthesis of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as other acute-phase reactants (13), modulating the immune response and participating in the regulation of body temperature (fever) (14). Thus, circulating IL-6 and its downstream CRP are potentially good indicators of the inflammatory status of the body. Proinflammatory cytokines, typically tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and anti-inflammatory cytokines, typically IL-10, also regulate the inflammatory response (15). Also, IL-4 and IL-10 are viewed as anti-inflammatory cytokines, because, when administered to animals with infection or inflammation, they are found to reduce the severity of the disease and reduce the production of IL-1 and TNF-α (16). Chronic low-grade inflammation may also influence the production of immunoglobulins (Igs) by B cells (17). Clinically, the systemic inflammatory response was evaluated by biochemical or hematologic markers, such as elevated CRP levels, hypoalbuminemia, accelerated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and increased numbers of white blood cells and neutrophils, as well as platelet counts (18).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during inflammation may be key effectors linking inflammation and increasing incidence of various chronic diseases (19–22). ROS are believed to play crucial roles in the disease pathogenesis through different mechanisms, causing damage to important cellular components (e.g., DNA, proteins, and lipids) and/or inducing a series of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines mediated in part by activation of the c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (23). Another pathway involved in the induction of cytokines is the activation of the transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which regulates immunity, inflammation, and cell survival (24–27). On the other hand, ROS are also known to be induced by TNF-α and other growth factors in some systems (28, 29).

In this study, we investigated the relationship of inflammatory cytokines and markers with the level of past A-bomb radiation exposure and natural aging. We found that A-bomb radiation has possibly contributed to these markers, albeit to a lesser extent than the contribution of natural aging. An inflammatory response is an orchestrated process that involves several protein families and several molecules with similar molecular functions. To gain further understanding of the interrelationships of inflammation-related markers, multivariate statistical analyses (principal factor analysis and principal component analysis) were used to uncover the underlying pathways of the inflammation response. Then, we proposed certain score indexes to identify a set of cytokines/markers most responsive to radiation and aging effects. Collectively, through the techniques of multivariate statistical analyses, the relationships can now be more clearly quantified, thereby implying that the radiation exposure may enhance the persistent inflammatory status of A-bomb survivors in conjunction with natural aging. Our study provides new insights into the interrelationship between radiation and aging-associated inflammation measures and models the inflammation as a function of radiation dose and age along with other epidemiological variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations

Our study subjects were the same A-bomb survivors as used in our previous studies (29, 30), comprising 182 nonexposed (<0.005 Gy) and 260 exposed (≥0.005 Gy) subjects. Briefly, the study subjects were randomly selected from the participants of the Adult Health Study (AHS) in Hiroshima (31), who visited the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) for a clinical health examination between March 1995 and April 1997 and provided written informed consent for research use of their peripheral blood samples. In the process of subject selection, we had excluded the subjects who carried or had experienced cancer or inflammation- associated diseases (e.g., current cold, chronic bronchitis, collagen disease, arthritis) at the time of blood collection. The blood samples were stored and used for measurements of plasma cytokines and some markers in our previous studies (29, 30) and, in this study, for measurement of plasma ROS levels. We took the radiation dose as the γ dose plus 10 times the neutron dose, using the skin doses (as a representative of whole-body irradiation) calculated by dosimetry system DS02 (30). This study was approved by RERF's ethics committee.

Measurements

In this study, we measured plasma ROS levels in duplicate, using the total ROS assay system that we have recently developed (31). We measured plasma IL-6, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10 levels in our previous study using an ultrasensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Quantikine HS, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), as well as plasma CRP levels using a CRP-Latex kit (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (32). ESR was measured by the Wintrobe method and adjusted for the hematocrit, as described previously (33). We quantitated Ig levels with human Ig quantitation kits (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA). The frequencies of cluster of differentiation (CD)4 (helper) and CD45RA-positive naive CD4 in the various lymphocyte fractions were measured as described previously (34). All measurements were performed using plasma samples collected and stored at the same time.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis of our data, we have made use of radiation dose data of individual subjects. Initially, 8 markers and cytokines, namely, ROS, IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, ESR, IL-4, IL-10, and Igs, were considered as the dependent variables to be analyzed after taking the logarithm at the base 10. This logarithmic transformation was applied to ensure the normality of the error distribution. We first investigated whether there were differences in 8 cytokines and markers by radiation exposure status (i.e., nonexposed and exposed). Then, we fitted multiple linear regression models (35) for each of the 8 markers. Age at the time of blood collection, gender of the subject, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI) values were taken as the covariates. The model considered for the logarithm of any of the markers (dependent variable, generically denoted, after taking the logarithm, by y) is given by Eq. 1:

| (1) |

Since these markers and cytokines were correlated with each other, and to elucidate the effects of radiation and aging on the pathways among these variables, we performed a principal factor analysis (36) on all 8 cytokines and markers. This analysis identifies latent factors, each of which is expressed as a linear combination of selected cytokines and markers. As part of this analysis, we performed a Varimax rotation with 3 underlying factors to add to the interpretability of the results by maximizing the extent to which each marker or cytokine was associated with only one factor. After we identified 3 latent, or unobservable, factors reflecting certain biological inflammation pathways or other connections (e.g., gene-gene interactions, use of common transcription factors) among certain subsets of the markers and cytokines, we used a principal component analysis to obtain a set of coefficients for the cytokines/markers in each of the three factors which maximize the amount of variation explained by that factor (37). The corresponding construct is commonly referred to as the first principal component. In all, we obtained three sets of the first principal components (henceforth referred to as the 1st_score, 2nd_score, and 3rd_score) corresponding to the 3 principal component analyses. We then investigated the effects of radiation, aging, and other epidemiological variables listed above on each of these first principal components by performing, in each case, a multiple regression analysis with the first principal components or scores as response variables. All of the above analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of subjects

Table 1 shows the characteristics of subjects by radiation exposure status and the means of inflammation markers after taking the logarithms. Corresponding P values of the 2-sample t tests show that for most of the markers, solely on the basis on means, the nonexposed and exposed groups cannot be distinguished.

Table 1.

Inflammation marker values for subjects selected from A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima, Japan

| Variable | Nonexposed, n = 182 | Exposed, n = 260 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 68.1 ± 8.1 | 68.3 ± 8.3 | 0.869 |

| Female/male ratio | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.394 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 2.8 | 22.6 ± 2.6 | 0.576 |

| Smokers (%) | 25.3 | 22.7 | 0.607 |

| Log(ROS) | 2.24 ± 0.10 | 2.26 ± 0.10 | 0.234 |

| Log(IL-6) | 0.13 ± 0.26 | 0.17 ± 0.28 | 0.156 |

| Log(TNF-α) | 0.18 ± 0.27 | 0.19 ± 0.27 | 0.690 |

| Log(CRP) | −1.32 ± 0.65 | −1.19 ± 0.62 | 0.031 |

| Log(ESR) | 1.19 ± 0.32 | 1.29 ± 0.30 | 0.001 |

| Log(IL-4) | 1.37 ± 0.42 | 1.45 ± 0.44 | 0.055 |

| Log(IL-10) | 0.45 ± 0.20 | 0.46 ± 0.24 | 0.412 |

| Log(Igs) | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.11 | 0.048 |

Values are means ± sd or as indicated. Nonexposed, subjects with radiation exposure <5 mGy; exposed, subjects with radiation exposure ≥ 5 mGy. P values determined by χ2 test for age, female/male ratio, BMI, and smokers; t test comparing means between radiation groups in others.

Linear regression analysis for each inflammation marker

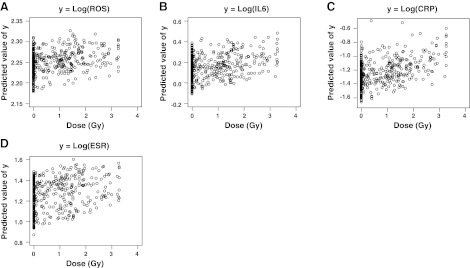

The results of multiple linear regression analysis for each marker are presented in Table 2. Statistically significant associations of cytokines or markers to radiation dose were observed, except for IL-4. However, the coefficient of determination (R2) in each regression was small. Four graphs given in Fig. 1 indicate the scatter plots of the predicted values of y, where y is the logarithm of ROS, IL-6, CRP, or ESR, respectively, as a function of radiation dose; at least visually, we could see little relationship to radiation dose, and these should not be concluded as biologically meaningful relationships. There was no improvement of the regression fit even after we included the interactions of covariates in the corresponding models.

Table 2.

Regression models for individual markers

| Response | Factor | Estimate | 95% CI | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log(ROS) | Dose (Gy) | 0.011 | (0.001, 0.021) | 0.081 |

| Gender | 0.033 | (0.013, 0.053) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.020 | (0.012, 0.029) | ||

| Smoking | 0.041 | (0.018, 0.063) | ||

| BMI | −0.001 | (−0.003, 0.002) | ||

| Log(IL-6) | Dose (Gy) | 0.047 | (0.021, 0.072) | 0.174 |

| Gender | −0.028 | (−0.080, 0.024) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.101 | (0.078, 0.124) | ||

| Smoking | 0.087 | (0.029, 0.145) | ||

| BMI | 0.006 | (−0.001, 0.013) | ||

| Log(TNF-α) | Dose (Gy) | 0.031 | (0.004, 0.057) | 0.083 |

| Gender | 0.063 | (0.009, 0.116) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.062 | (0.039, 0.086) | ||

| Smoking | 0.011 | (−0.049, 0.071) | ||

| BMI | 0.005 | (−0.002, 0.012) | ||

| Log(CRP) | Dose (Gy) | 0.111 | (0.050, 0.173) | 0.094 |

| Gender | 0.018 | (−0.108, 0.144) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.103 | (0.048, 0.159) | ||

| Smoking | 0.082 | (−0.059, 0.223) | ||

| BMI | 0.043 | (0.026, 0.061) | ||

| Log(ESR) | Dose (Gy) | 0.065 | (0.037, 0.093) | 0.248 |

| Gender | 0.235 | (0.178, 0.291) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.069 | (0.044, 0.094) | ||

| Smoking | −0.026 | (−0.090, 0.037) | ||

| BMI | −0.005 | (−0.013, 0.003) | ||

| Log(IL-4) | Dose (Gy) | −0.018 | (−0.061, 0.026) | 0.030 |

| Gender | −0.063 | (−0.151, 0.026) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.057 | (0.019, 0.096) | ||

| Smoking | v0.066 | (−0.165, 0.032) | ||

| BMI | 0.005 | (−0.007, 0.017) | ||

| Log (IL-10) | Dose (Gy) | 0.025 | (0.003, 0.048) | 0.048 |

| Gender | −0.039 | (−0.085, 0.007) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.035 | (0.015, 0.056) | ||

| Smoking | 0.016 | (−0.035, 0.067) | ||

| BMI | 0.007 | (0.000, 0.013) | ||

| Log(Igs) | Dose (Gy) | 0.015 | (0.004, 0.025) | 0.056 |

| Gender | 0.021 | (−0.001, 0.042) | ||

| Age (10 yr) | 0.012 | (0.002, 0.021) | ||

| Smoking | −0.019 | (−0.042, 0.005) | ||

| BMI | −0.001 | (−0.004, 0.002) |

Figure 1.

Predicted values of selected markers vs. radiation dose (based on individual regression models, Eq. 1). A) ROS. B) IL-6. C) CRP. D) ESR.

Principal factor analyses of cytokines and markers

Principal factor analysis revealed that 3 factors explained different characteristics among cytokines and markers. The most important factor explained 31% of the total variation and had large coefficients for Log(ROS), Log(IL-6), Log(CRP), and Log(ESR); the second factor explained 14% of the total variation and had large coefficients for Log(TNF-α), Log(ESR), and Log(Igs); and the third factor explained 13% of the total variation and had large coefficients for Log(TNF-α), Log(IL-4), and Log(IL-10). This implies the presence of some latent factors possibly related to different immunological pathways or mechanisms, each involving a unique set of the cytokines and markers (that is, those with large coefficients for that particular factor). Then, the principal component analysis was conducted separately for the aforementioned cytokines and markers strongly associated with each of the first, second, and third factors to create scores quantifying the information of that latent factor. Tables 3–5 show these 3 correlation matrices used in the principal component analyses. All correlations are positive and lie between 0.12 and 0.42, indicating a low to moderate interrelationship among the variables (37).

Table 3.

Correlation matrix for logarithms of ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR

| Variable | Log(IL-6) | Log(CRP) | Log(ESR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log(ROS) | 0.329 | 0.254 | 0.286 |

| Log(IL-6) | – | 0.410 | 0.327 |

| Log(CRP) | – | – | 0.312 |

Table 4.

Correlation matrix for logarithms of TNF-α, ESR, and Igs

| Variable | Log(ESR) | Log (Igs) |

|---|---|---|

| Log (TNF-α) | 0.300 | 0.301 |

| Log(ESR) | – | 0.421 |

Table 5.

Correlation matrix for logarithms of TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10

| Variable | Log (IL-4) | Log (IL-10) |

|---|---|---|

| Log (TNF-α) | 0.133 | 0.277 |

| Log (IL-4) | – | 0.125 |

Regression model for inflammation scores

Only the first principal component of each of the 3 principal component analyses contained more information than the original single cytokines and markers. We call those first principal components the 1st_score, 2nd_score, and 3rd_score, which quantify the first, second, and third unobserved latent inflammation mechanisms implied by factor analysis, respectively. These scores are obtained by Eqs. 2–4:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

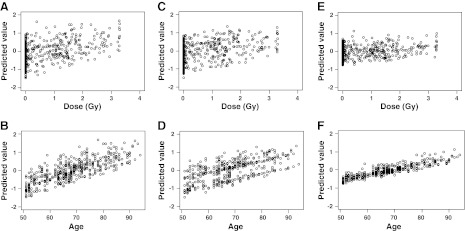

where the prefix s is used to indicate that individual (logged) variables have been standardized to have 0 means and sd of 1. We view these scores as single multivariate indices of inflammation, each of which incorporates the inflammation characteristics of the associated group of variables into a single variable. With y as scores defined in Eqs. 2–4, we fit the model Eq. 1, resulting, in each case, in a prediction equation. As shown in Table 6, all 3 models are statistically significant (with P<0.001), with R2 = 19.0, 19.1, and 8.8%, respectively: considerably better than models for most of the individual markers, thereby implying superior fits and better predictability. More important, the inflammation scores are independent of each other. The associations of the 1st_score, 2nd_score, and 3rd_score with the explanatory variables; i.e., radiation, gender, age, smoking, and BMI, in terms of the regression model Eq. 1, are also shown in Table 6. All the variables in the model of the 1st_score are statistically significant, with very small P values, an exception being the BMI, for which the statistical significance is somewhat marginal. More specifically, radiation, gender, and age are statistically significant in both models for the 1st_score and 2nd_score. Also, radiation and age are significant for the 3rd_score. In addition, this score may be closely associated with BMI, but not with gender and smoking. Standard error values, also presented in Table 6, of all the variables are small, thereby supporting, as desired, the good precision of the estimates of the respective slopes. Figure 2 shows the plots of predicted values of the 1st_score (Fig. 2A, B), 2nd_score (Fig. 2C, D), and 3rd_score (Fig. 2E, F) among study subjects against their given dose and age at the time of collecting plasma samples, respectively. In each of the 6 images, an increasing trend for the score is self-evident. However, in terms of the scatter in these plots, the effect of aging is more pronounced than the effect of radiation, since points are more tightly clustered around the trend in the former case.

Table 6.

Regression model for scores of inflammation pathways (based on leading principal components as response)

| Factor | Estimate | 95% CI | P | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st_score | ||||

| Dose (Gy) | 0.332 | (0.204, 0.461) | <0.001 | 0.190 |

| Gender | 0.475 | (0.213, 0.737) | <0.001 | |

| Age (10 yr) | 0.482 | (0.367, 0.597) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | 0.383 | (0.091, 0.676) | 0.011 | |

| BMI | 0.037 | (0.001, 0.073) | 0.045 | |

| 2nd_score | ||||

| Dose (Gy) | 0.267 | (0.148, 0.386) | <0.001 | 0.191 |

| Gender | 0.689 | (0.446, 0.932) | <0.001 | |

| Age (10 yr) | 0.304 | (0.214, 0.427) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | 0.001 | (−0.406, 0.136) | 0.329 | |

| BMI | 0.035 | (−0.039, 0.028) | 0.745 | |

| 3rd_score | ||||

| Dose (Gy) | 0.124 | (0.011, 0.238) | 0.032 | 0.088 |

| Gender | −0.025 | (−0.257, 0.207) | 0.836 | |

| Age (10 yr) | 0.304 | (0.203, 0.406) | <.001 | |

| Smoking | 0.001 | (−2.257, 0.260) | 0.991 | |

| BMI | 0.035 | (0.004, 0.067) | 0.030 |

Figure 2.

Predicted inflammation scores as functions of radiation dose and age (as calculated for all study subjects by the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd scores, comprised of ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR; TNF-α, ESR, and Igs; and TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10, respectively). A) 1st_score vs. dose. B) 1st_score vs. age. C) 2nd_score vs. dose. D) 2nd_score vs. age. E) 3rd_score vs. dose. F) 3rd_score vs. age.

Inflammation scores and CD4 or naive CD4 T-cell frequencies

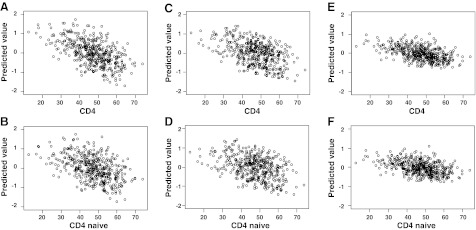

We also investigated the association between the inflammation scores and CD4 or naive CD4 T-cell frequencies, respectively, by adding CD4 T-cell frequencies and naive CD4 T-cell frequencies, separately, into the regression models mentioned above (Fig. 3). The estimates of the regression coefficient in each model were −0.022 (CD4, P<0.001) and −0.016 (naive CD4, P=0.008) for the 1st_score, −0.017 (CD4, P=0.005) and −0.015 (naive CD4, P=0.010) for the 2nd_ score, and −0.006 (CD4, P=0.24) and −0.005 (naive CD4, P=0.38) for the 3rd_score. There were negative correlations between inflammation scores and helper T-cell measurements, while only the associations of the 1st_score and 2nd_score were statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Association between the inflammation scores and CD4 or CD4 naive T cell frequency. A) 1st_score vs. CD4 T cells. B) 1st_score vs. naive CD4 T cells. C) 2nd_score vs. CD4 T cells. D) 2nd_score vs. naive CD4 T cells. E) 3rd_score vs. CD4 T cells. F) 3rd_score vs. naive CD4 T cells.

Radiation effects on age-dependent inflammation

The regression slope coefficients in the fitted model shown in Table 6 can also be used to compare the effect of radiation dose with the corresponding effect of aging. Specifically, for the inflammation pathway quantified by the 1st_score, where βdose = 0.33 and βage = 0.48, when viewed in the context of the inflammation explained by the 4 markers in the 1st_score, 1 Gy of radiation exposure is approximately equivalent to βdose/βage = 0.33/0.48 = 0.69 decade of aging, or an age increase of 6.9 yr. In view of the small standard error values of both slope coefficients, this estimate is also expected to be reasonably accurate. Similarly for the inflammation pathways quantified by the 2nd_score and 3rd_score, 1 Gy of radiation exposure is approximately equivalent to 0.27/0.33 = 0.82 and 0.12/0.30 = 0.40 decades of aging, respectively. For the 2nd_score and 3rd_score, we calculated these ratios using the coefficients of models chosen with minimum Akaike's information criterion (AIC). The percentage increments in each inflammation score for the unit change in dose or age can be measured as 100 * (exp(βdose) − 1) and 100 * (exp(βage) − 1), respectively. Accordingly, corresponding to 1 Gy of radiation exposure, the percentage increments in 1st_score, 2nd_score, and 3rd_score are approximately 39, 31, and 13%, respectively, while for one decade of extra age, the score increments are approximated as 62, 39, and 35%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we measured plasma ROS levels in A-bomb survivors and used those results and previously measured results of plasma markers and cytokines for evaluation of radiation and aging effects on immune and systemic markers of inflammation. The analyses included both inflammatory cytokines and markers (ROS, IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, ESR, and Igs) and antiinflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10). IL-4, IL-6, TNF-α, and, CRP play a central role in the coordination of the inflammatory response as key proinflammatory cytokines. In the previous study, plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines and biomarkers (IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, and ESR) increased significantly with radiation dose or age (32, 38). We demonstrated here that 7 of these 8 cytokines and markers, including plasma ROS levels, were correlated with increasing age and radiation dose. However, the coefficient of determination in each regression was small. Then, to assess the biologically significant relationship between inflammation and radiation exposure or aging, we used multivariate statistical analyses and evaluated the systemic markers of inflammation as scores calculated by linear combinations of selected cytokines and markers. Principal factor analysis revealed that 3different factors explained the correlation structure among cytokines and markers. The first, second, and third factors had large coefficients for ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR; TNF-α, ESR, and Igs; and TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10, respectively. These factors imply the presence of some latent variables possibly related to immunological pathways or mechanisms, each involving the cytokines/markers with large coefficients for that factor. In the association of the 1st_score, 2nd_score, and 3rd_score with the explanatory variables, radiation, gender, and age were statistically significant in the models of the 1st_score and 2nd_score. These results indicate that linear combinations of ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR and TNF-α, ESR, and Igs generated such a score that was the most indicative of inflammation and revealed clear dependences on radiation dose and aging and that there may be two inflammation pathways related to radiation. One pathway is involved in an ROS-dependent pathway related to IL-6 and CRP. The other is in an ROS-independent pathway related to TNF-α and Igs. Our results indicated that the systemic markers of inflammation might be accelerated by these ROS-dependent and -independent pathways.

The ROS measured in the plasma at the time of sampling indicates an equilibrium level that is constitutively produced by cells and reflects the oxidative state of the body. It has been known that ROS perform essential roles in inflammation and immune responses to pathogens, including bacterial killing through the production of superoxide by reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases during the respiratory burst in activated macrophages and neutrophils (39,40). One possibility is that the pathways related to these NADPH oxidases may be involved in ROS generation and modulate by aging and radiation. Evidence that high serum concentrations of cytokines and inflammatory proteins were associated with high levels of ROS and low levels of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase is also of particular interest (41). Circulating levels of TNF-α and IL-6 increased with age in the general population (42); aging was also associated with increased levels of acute-phase proteins, such as CRP and serum amyloid A (43). Moreover, whereas IFN-α and IFN-γ production decreased in the elderly, IL-4 and IL-10 production increased (44), as did production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (45). Aging is also found to cause the increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and ROS, both of which have been associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis (46, 47). Inflammation-induced formation of ROS is often indicative of the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, and its implications for aging provide strong support for the hypothetic involvement of interrelated inflammation and oxidative stress in aging processes.

It has been reported that vascular endothelial cells might also be involved in production of many inflammation-related cytokines and ROS in plasma and that their extensive production has been implicated in diseases such as atherosclerosis through the induction of chronic activation of the vascular endothelium and components of the immune system (48). It is likely that elevated plasma levels of CRP and IL-6 are risk factors for cardiovascular disease (49). Indeed, human CRP and complement activation are major mediators of ischemic myocardial injury (50). Experimental and clinical studies have suggested increased production of ROS both in animals and patients with acute and chronic heart failure (51–55). Our results indicate that a linear combination of ROS, IL-6, CRP, and ESR (Eq. 2) generated such a score that was the most indicative of inflammation and revealed clear dependences on radiation dose and aging. These results suggest that, collectively, radiation exposure may enhance the persistent inflammatory status of A-bomb survivors in conjunction with natural aging. Given the potential implications of our findings, a follow-up study with an increased number of subjects or retrospective study with the use of stored plasma samples, in association with the development of various inflammation-associated diseases, is warranted to confirm the clinical benefit of these scores.

It has been reported that a regression analysis indicates statistically significant association between radiation dose and leukocyte counts but not neutrophil counts (33). In addition, long-term immunological studies of A-bomb survivors have revealed that the percentages of CD4 (helper) T-cell populations, especially those of CD45RA+ (naive) CD4 T cells, decreased in peripheral blood as radiation dose or age increased (34, 56). In our present studies, score values correlated negatively with the percentages of CD4 and naive CD4 T cells. We therefore suppose that elevated inflammatory score values indicate certain mechanisms which play a role in the attenuation of T-cell immunity in A-bomb survivors. Furthermore, we have previously reported that the percentages of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes decreased significantly in A-bomb survivors who had a history of myocardial infarction, indicating that such an immunological modification may be related to the increased risk of the disease (57). Taken together, this immunological balance impaired by aging and radiation exposure might result in acceleration of inflammatory status related to those multiple ROS-dependent and -independent inflammatory pathways.

To obtain further support of the hypothesis that A-bomb radiation has accelerated immunological aging, which, in turn, might lead to long-lasting inflammation, we are conducting a longitudinal analysis that assesses changes in immunological and clinical status with radiation exposure and aging in the A-bomb survivor population, on the basis of a number of immunological and inflammatory biomarkers interacting with each other. We have also begun to analyze genotype-phenotype associations concerning immune-related genes to take into account the genetically-regulated production and function of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which may in part explain the interindividual variation in inflammatory response. Based on the studies mentioned above, it is expected that we will be able to derive the basis for the development of an integrated scoring system to verify our hypothesis of acceleration of immunosenescence due to radiation exposure.

Acknowledgments

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF; Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan) is a private, nonprofit foundation funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the latter in part through DOE award DE-HS0000031 to the National Academy of Sciences. This was based on RERF Research Protocols 1-93, 4-02, and 3-09 and was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science, and Technology; the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; and the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; contract HHSN272200900059C).

The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the two governments.

Footnotes

- A-bomb

- atomic bomb

- AHS

- adult health study

- BMI

- body mass index

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- CRP

- C-reactive protein

- ESR

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Ig

- immunoglobulin

- IL

- interleukin

- JNK

- c-Jun-N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NADPH

- nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- RERF

- Radiation Effects Research Foundation

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor α

REFERENCES

- 1. Douple E. B., Mabuchi K., Cullings H. M., Preston D. L., Kodama K., Shimizu Y., Fujiwara S., Shore R. E. (2011) Long-term radiation-related health effects in a unique human population: lessons learned from the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 5(Suppl. 1), S122–S133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kodama K., Sasaki H., Shimizu Y. (1990) Trend of coronary heart disease and its relationship to risk factors in a Japanese population: a 26-year follow-up, Hiroshima/Nagasaki study. Jpn. Circ. J. 54, 414–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pierce D. A., Shimizu Y., Preston D. L., Vaeth M., Mabuchi K. (1996) Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 12, Part I. Cancer: 1950–1990. Radiat. Res. 146, 1–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharp G. B., Mizuno T., Cologne J. B., Fukuhara T., Fujiwara S., Tokuoka S., Mabuchi K. (2003) Hepatocellular carcinoma among atomic bomb survivors: significant interaction of radiation with hepatitis C virus infections. Int. J. Cancer 103, 531–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Preston D. L., Ron E., Tokuoka S., Funamoto S., Nishi N., Soda M., Mabuchi K., Kodama K. (2007) Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1998. Radiat. Res. 168, 1–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ozasa K., Shimizu Y., Suyama A., Kasagi F., Soda M., Grant E. J., Sakata R., Sugiyama H., Kodama K. (2012) Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, Report 14, 1950–2003: an overview of cancer and noncancer diseases. Radiat. Res. 177, 229–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bretz W. A., Weyant R. J., Corby P. M., Ren D., Weissfeld L., Kritchevsky S. B., Harris T., Kurella M., Satterfield S., Visser M., Newman A. B. (2005) Systemic inflammatory markers, periodontal diseases, and periodontal infections in an elderly population. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 1532–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ungvari Z., Csiszar A., Kaley G. (2004) Vascular inflammation in aging. Herz. 29, 733–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krabbe K. S., Pedersen M., Bruunsgaard H. (2004) Inflammatory mediators in the elderly. Exp. Gerontol. 39, 687–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris T. B., Ferrucci L., Tracy R. P., Corti M. C., Wacholder S., Ettinger W. H., Jr., Heimovitz H., Cohen H. J., Wallace R. (1999) Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am. J. Med. 106, 506–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van der Meide P. H., Schellekens H. (1996) Cytokines and the immune response. Biotherapy 8, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pannen B. H., Robotham J. L. (1995) The acute-phase response. New Horiz. 3, 183–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lu Z. Y., Brailly H., Wijdenes J., Bataille R., Rossi J. F., Klein B. (1995) Measurement of whole body interleukin-6 (IL-6) production: prediction of the efficacy of anti-IL-6 treatments. Blood 86, 3123–3131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fey G. H., Hattori M., Hocke G., Brechner T., Baffet G., Baumann M., Baumann H., Northemann W. (1991) Gene regulation by interleukin 6. Biochimie (Paris) 73, 47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tracey K. J. (2002) The inflammatory reflex. Nature 420, 853–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dinarello C. A. (1991) Interleukin-1 and interleukin-1 antagonism. Blood 77, 1627–1652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Papadaki H. A., Eliopoulos D. G., Ponticoglou C., Eliopoulos G. D. (2001) Increased frequency of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in patients with nonimmune chronic idiopathic neutropenia syndrome. Int. J. Hematol. 73, 339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roxburgh C. S., McMillan D. C. (2010) Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 6, 149–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macarthur M., Hold G. L., El-Omar E. M. (2004) Inflammation and Cancer II. Role of chronic inflammation and cytokine gene polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal malignancy. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G515–G520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Willcox J. K., Ash S. L., Catignani G. L. (2004) Antioxidants and prevention of chronic disease. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 44, 275–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peters T., Weiss J. M., Sindrilaru A., Wang H., Oreshkova T., Wlaschek M., Maity P., Reimann J., Scharffetter-Kochanek K. (2009) Reactive oxygen intermediate-induced pathomechanisms contribute to immunosenescence, chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. Mech. Ageing Dev. 130, 564–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Federico A., Morgillo F., Tuccillo C., Ciardiello F., Loguercio C. (2007) Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in human carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer. 121, 2381–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung J., Lee H. S., Chung H. Y., Yoon T. R., Kim H. K. (2008) Salicylideneamino-2-thiophenol inhibits inflammatory mediator genes (RANTES, MCP-1, IL-8 and HIF-1alpha) expression induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide via MAPK pathways in rat peritoneal macrophages. Biotechnol. Lett. 30, 1553–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papa S., Zazzeroni F., Pham C. G., Bubici C., Franzoso G. (2004) Linking JNK signaling to NF-kappaB: a key to survival. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5197–5208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Papa S., Bubici C., Zazzeroni F., Pham C. G., Kuntzen C., Knabb J. R., Dean K., Franzoso G. (2006) The NF-kappaB-mediated control of the JNK cascade in the antagonism of programmed cell death in health and disease. Cell Death Differ. 13, 712–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wullaert A., Heyninck K., Beyaert R. (2006) Mechanisms of crosstalk between TNF-induced NF-kappaB and JNK activation in hepatocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1090–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bubici C., Papa S., Dean K., Franzoso G. (2006) Mutual cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor-kappa B: molecular basis and biological significance. Oncogene 25, 6731–6748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goossens V., De Vos K., Vercammen D., Steemans M., Vancompernolle K., Fiers W., Vandenabeele P., Grooten J. (1999) Redox regulation of TNF signaling. Biofactors 10, 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sone H., Akanuma H., Fukuda T. (2010) Oxygenomics in environmental stress. Redox Rep. 15, 98–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cullings H. M., Fujita S., Funamoto S., Grant E. J., Kerr G. D., Preston D. L. (2006) Dose estimation for atomic bomb survivor studies: its evolution and present status. Radiat. Res. 166, 219–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hayashi I., Morishita Y., Imai K., Nakamura M., Nakachi K., Hayashi T. (2007) High-throughput spectrophotometric assay of reactive oxygen species in serum. Mutat. Res. 631, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayashi T., Morishita Y., Kubo Y., Kusunoki Y., Hayashi I., Kasagi F., Hakoda M., Kyoizumi S., Nakachi K. (2005) Long-term effects of radiation dose on inflammatory markers in atomic bomb survivors. Am. J. Med. 118, 83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neriishi K., Nakashima E., Delongchamp R. R. (2001) Persistent subclinical inflammation among A-bomb survivors. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 77, 475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kusunoki Y., Kyoizumi S., Hirai Y., Suzuki T., Nakashima E., Kodama K., Seyama T. (1998) Flow cytometry measurements of subsets of T, B and NK cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes of atomic bomb survivors. Radiat. Res. 150, 227–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khattree R., Naik D. N. (1999) Applied Multivariate Statistics with SAS Software, SAS Press/Wiley, Cary, NC, USA [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khattree R., Naik D. N. (2000) Multivariate Data Reduction and Discrimination with SAS Software, SAS Press/Wiley, Cary, NC, USA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bishop Y. M., Fienberg S. E., Holland P. W., Light R. J. (2007) Discrete Multivariate Analysis: Theory and Practice, Springer, London [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayashi T., Kusunoki Y., Hakoda M., Morishita Y., Kubo Y., Maki M., Kasagi F., Kodama K., Macphee D. G., Kyoizumi S. (2003) Radiation dose-dependent increases in inflammatory response markers in A-bomb survivors. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 79, 129–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lambeth J. D. (2004) NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kanayama A., Miyamoto Y. (2007) Apoptosis triggered by phagocytosis-related oxidative stress through FLIPS down-regulation and JNK activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 1344–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mantovani G., Maccio A., Madeddu C., Mura L., Gramignano G., Lusso M. R., Mulas C., Mudu M. C., Murgia V., Camboni P., Massa E., Ferreli L., Contu P., Rinaldi A., Sanjust E., Atzei D., Elsener B. (2002) Quantitative evaluation of oxidative stress, chronic inflammatory indices and leptin in cancer patients: correlation with stage and performance status. Int. J. Cancer 98, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dobbs R. J., Charlett A., Purkiss A. G., Dobbs S. M., Weller C., Peterson D. W. (1999) Association of circulating TNF-alpha and IL-6 with ageing and parkinsonism. Acta Neurol. Scand. 100, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ballou S. P., Lozanski F. B., Hodder S., Rzewnicki D. L., Mion L. C., Sipe J. D., Ford A. B., Kushner I. (1996) Quantitative and qualitative alterations of acute-phase proteins in healthy elderly persons. Age Ageing 25, 224–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Solana R., Mariani E. (2000) NK and NK/T cells in human senescence. Vaccine 18, 1613–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rink L., Cakman I., Kirchner H. (1998) Altered cytokine production in the elderly. Mech. Ageing Dev. 102, 199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pedersen B. K., Bruunsgaard H. (2003) Possible beneficial role of exercise in modulating low-grade inflammation in the elderly. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 13, 56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cubbon R. M., Kahn M. B., Wheatcroft S. B. (2009) Effects of insulin resistance on endothelial progenitor cells and vascular repair. Clin. Sci. (London) 117, 173–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Galkina E., Ley K. (2009) Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis (*). Ann. Rev. Immunol. 27, 165–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ridker P. M., Rifai N., Stampfer M. J., Hennekens C. H. (2000) Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation 101, 1767–1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Griselli M., Herbert J., Hutchinson W. L., Taylor K. M., Sohail M., Krausz T., Pepys M. B. (1999) C-reactive protein and complement are important mediators of tissue damage in acute myocardial infarction. J. Exp. Med. 190, 1733–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cesselli D., Jakoniuk I., Barlucchi L., Beltrami A. P., Hintze T. H., Nadal-Ginard B., Kajstura J., Leri A., Anversa P. (2001) Oxidative stress-mediated cardiac cell death is a major determinant of ventricular dysfunction and failure in dog dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 89, 279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ferrari R., Guardigli G., Mele D., Percoco G. F., Ceconi C., Curello S. (2004) Oxidative stress during myocardial ischaemia and heart failure. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 1699–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Giordano F. J. (2005) Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 500–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Landmesser U., Spiekermann S., Dikalov S., Tatge H., Wilke R., Kohler C., Harrison D. G., Hornig B., Drexler H. (2002) Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine-oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation 106, 3073–3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li J. M., Shah A. M. (2004) Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. 287, R1014–R1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kusunoki Y., Yamaoka M., Kasagi F., Hayashi T., Koyama K., Kodama K., MacPhee D. G., Kyoizumi S. (2002) T cells of atomic bomb survivors respond poorly to stimulation by Staphylococcus aureus toxins in vitro: does this stem from their peripheral lymphocyte populations having a diminished naive CD4 T-cell content? Radiat. Res. 158, 715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kusunoki Y., Kyoizumi S., Yamaoka M., Kasagi F., Kodama K., Seyama T. (1999) Decreased proportion of CD4 T cells in the blood of atomic bomb survivors with myocardial infarction. Radiat. Res. 152, 539–543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]