Abstract

Links between microbial community assemblages and geogenic factors were assessed in 187 soil samples collected from four metal-rich provinces across Australia. Field-fresh soils and soils incubated with soluble Au(III) complexes were analysed using three-domain multiplex-terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism, and phylogenetic (PhyloChip) and functional (GeoChip) microarrays. Geogenic factors of soils were determined using lithological-, geomorphological- and soil-mapping combined with analyses of 51 geochemical parameters. Microbial communities differed significantly between landforms, soil horizons, lithologies and also with the occurrence of underlying Au deposits. The strongest responses to these factors, and to amendment with soluble Au(III) complexes, was observed in bacterial communities. PhyloChip analyses revealed a greater abundance and diversity of Alphaproteobacteria (especially Sphingomonas spp.), and Firmicutes (Bacillus spp.) in Au-containing and Au(III)-amended soils. Analyses of potential function (GeoChip) revealed higher abundances of metal-resistance genes in metal-rich soils. For example, genes that hybridised with metal-resistance genes copA, chrA and czcA of a prevalent aurophillic bacterium, Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34, occurred only in auriferous soils. These data help establish key links between geogenic factors and the phylogeny and function within soil microbial communities. In particular, the landform, which is a crucial factor in determining soil geochemistry, strongly affected microbial community structures.

Keywords: soil, landform, bacteria, gold, microarray, Australia

Introduction

Identifying drivers of microbial community structures in soils is challenging. Difficulties arise because of the complexity of soil ecosystems, where large number of niches provide for high levels of species diversity and complex ecosystem interactions (Fierer and Jackson, 2006). Environmental factors, for example, soil-type, vegetation, landuse and associated physicochemical parameters, for example, C– N–, water content and pH, have been linked to soil microbial structures and activities (Acosta-Martinez et al., 2008; Lauber et al., 2008; Wakelin et al., 2008; Drenovsky et al., 2010). In contrast, the importance of geogenic drivers, comprising geomorphological, geological and geochemical factors such as the landform, the underlying lithology and the presence of buried mineral deposits (expressed in overlying soils as elevated concentrations of mobile metals) are less well understood (Viles, 2011, in press). As geogenic influences are likely to develop over extended ‘geologic' periods of time, their effects may be masked by ‘short term' changes in vegetation, landuse or anthropogenic influences (Viles, 2011, in press). However, these are likely to be second order influences within ecosystems, which are predominantly driven by geogenic factors.

High concentrations of metals, for example in soils exposed to industrial pollution or mining, substantially alter microbial communities (Baker and Banfield 2003; Hu et al., 2007; Kock and Schippers, 2008; Denef et al., 2010). Similarly, amendment of soils with Cu, Pb, Zn and Cd strongly influences resident bacterial communities (Bååth, 1989; Abaye et al., 2005; Wakelin et al., 2010a, 2010b). In contrast, few studies have looked at natural systems in which physical and biogeochemical processes have formed ‘enrichment haloes' of metals in soils overlying mineral deposits (Aspandiar et al., 2008). One study of soils overlying a base metal (Cu, Pb and Zn) deposit in Western Australia has shown that the solubilisation, transport and deposition of metals are mediated by resident plant and microbial communities, in turn altering the structure of microbial communities in the metal-rich soils overlying the deposit (Wakelin et al., 2012b). Other studies have shown that soil microbial communities mediate Au mobilisation, and that underlying Au deposits may influence microbial communities (Reith and McPhail, 2006; Reith and Rogers, 2008).

This is the first study to use a comprehensive set of molecular tools, that is, multiplex-terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (M-TRFLP), and high-density phylogenetic (PhyloChip) and functional (GeoChip) microarrays, in combination with field mapping and geochemical analyses, to assess the influences of geogenic factors on soil microbial communities. Hence, we assess: (i) if soil microbial community structure and functioning potential (as interpreted from the occurrence of specific genes on GeoChip microarrays) are influenced by landform, lithology and underlying Au deposits; (ii) how underlying geochemical parameters define these influences; and (iii) if environmentally relevant concentrations of Au affect microbial communities.

Materials and methods

Field sites and sampling

Minimal landuse sites overlying Au deposits in remote Australia were sampled. Here, soils have developed over thousands to millions of years under tectonically stable conditions. Auriferous and non-auriferous soils were collected from four sampling areas, these are Old Pirate, Tomakin Park, Humpback and Wildcat; a description of environmental characteristics and references is given in Supplementary Table S1. Old Pirate is located in the Tanami region of the Northern Territory (Figure 1). Across the site soil-type, vegetation and underlying lithology are uniform, allowing for the influence of the landform, as the dominant geogenic factor, to be assessed (Supplementary Table S1). Soils were collected in October 2009 from the A-horizon (at 0.1–0.15 m depth) along a nine kilometre traverse covering erosional, colluvial and alluvial landforms. The Tomakin Park site is located in New South Wales (Figure 1). The site has a uniform underlying lithology (phyllitic schist), landform (colluvium) and vegetation settings; hence the influence of soil horizons was assessed (Supplementary Table S1). Soils were collected in October 2007 along a 400-m traverse at depths of 0.03–0.05 and 0.15–0.2 m for Ah- and B-horizons, respectively. The (contiguous) Wildcat and Humpback sites are located in the Lawlers district of Western Australia (Figure 1). Samples were collected in June 2008 from the A-horizon (0.1–0.15 m) over an 8-km polygon covering different lithologies (mafic and granitic rocks) and landforms (erosional, colluvial, alluvial and depositional).

Figure 1.

Map of Australia showing the Old Pirate, Tomakin Park, Humpback and Wildcat sites in the Northern Territory, New South Wales and Western Australia, respectively.

At each of the 187 sampling locations, 50-ml centrifuge tubes of soil were collected under field-sterile conditions. Landforms and soil types were classified using the Australian landform and soil classification systems, respectively (Isbell, 2002; Pain, 2008). Samples for DNA extraction were frozen on-site. Tubes stored at ambient temperature were used for geochemical analyses. At three locations, 10 kg of soil was collected for microcosm experiments. These soils were homogenised, sieved to <2 mm fraction, stored in sterile plastic bags and refrigerated at 4 °C.

Soil microcosms experiments

To assess the effect of soluble Au(III) complexes on community assemblages, microcosm experiments were conducted with Old Pirate, Wildcat and Humpback soils, following Reith and Rogers (2008). Microcosms consisted of sterile 50 ml tubes containing 40 g d.w. (dry weight) soil. Soils were amended with 0, 50, 1000 and 100 000 ng Au(III)-chloride g−1 d.w. soil and incubated aerobically at 90% water holding capacity in the dark. At 0, 2, 10 and 30 days, three replicates tubes were sampled from each experiment; DNA was extracted and analysed by M-TRFLP.

Assessment of community assemblages and functional potential

Nucleic acid extraction, quantification and quality control

For M-TRFLP, DNA was extracted in duplicate from 0.25 g of homogenised field and microcosm soils using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For microarray analyses, DNA was extracted in duplicate from 10 g of soil using the PowerMAX Soil Mega Prep DNA Isolation kit (Mo Bio). Duplicate extractions were combined, DNA was purified (phenol:chloroform), precipitated with isopropanol and quantified (Quant-iT; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Multiplex-terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism

Bacterial, archaeal and fungal communities were characterised using M-TRFLP of the small subunit rRNA gene (Singh et al., 2006). Primer sets and reagents are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Multiplex-PCR (PCRs, 25 μl) used Qiagen (Venlo, The Netherlands) HotStar Taq chemistry and PCR consisted of 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s and a final extension step for 10 min at 72 °C (Singh et al., 2006). Lengths of the final products are listed in Supplementary Table S2 and were verified via gel electrophoresis. PCR products were purified (WizardSV; Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA), and 100 ng digested with 20 U of MspI, HaeIII and TaqI for 3 h at 37 °C or 65 °C. Capillary separation of TRFs was conducted by the Australian Genome Research Facility. TRFs were scored in GeneMarker (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA) at a detection limit of 200 fluorescent units; TRFs differing ±0.5 base pairs were binned together. Peak heights were used as a measure of abundance while richness was based on the number of TRFs obtained.

Similarity matrices were generated on square root transformed abundance data using the Bray–Curtis method (Bray and Curtis, 1957). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) combined with canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP; Anderson et al., 2008) were used to test the effects of geogenic factors. PERMANOVA analyses were conducted using partial sums of squares, on 9999 permutations of residuals under a reduced model. Associations between microbial and geochemical data sets were assessed using RELATE tests (permutation-derived Mantel-type testing). When significant (P<0.05) relationships occurred, distance-based linear modelling was used to assess geochemical parameters best explaining the variability within the microbial data set. Geochemical parameters significant influencing microbial structures are shown as vector overlays in CAP plots. Multivariate analysis was conducted using PRIMER6 and PERMANOVA+ (Primer-E Ltd, Ivybridge, UK). Statistical routines are described in Clarke and Warwick (2001) and Anderson et al. (2008).

Microarray analysis (PhyloChip and GeoChip)

The G2-PhyloChip microarray was used to characterise the bacterial community composition (Brodie et al., 2006). Key samples were chosen that best represented influence by geogenic factors (CAP analyses on the geochemical data sets). Amplification of 16S rRNA genes, purification of products, labelling of DNA and hybridisation were conducted following Brodie et al. (2006) using the reaction chemistry described in Wakelin et al. (2012b). Hybridised arrays were stained and washed on an Affymetrix fluidic station (Brodie et al., 2006). Following scanning, data were processed following Brodie et al. (2006) and DeSantis et al. (2007). Data were imported into PhyloTrac for scoring of taxa (Schatz et al., 2010). Operational taxonomic units were deemed detected by a positive fraction of probe-pair matches ⩾0.9. Taxa were ranked by relative abundance, and the 500 taxa with the highest intensities across all samples were aggregated into a data set, representing the dominant community. The taxonomical hierarchy for each taxon was determined and the distribution of phyla/classes plotted; taxa representing <1% of the total abundance were combined as ‘other'. Data were aggregated to phylum/class levels and log transformed. Similarity percentage analysis was used to identify groups that that discriminate between auriferous and non-auriferous soils (P<0.1; Clarke and Warwick, 2001).

Key samples from Old Pirate and Tomakin were analysed using GeoChip 3.0 (He et al., 2010). Arrays were scanned by ScanArray Express Microarray Scanner (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 633 nm using a laser power of 90% and a photomultiplier tube gain of 75%. ImaGene v.6.0 (Biodiscovery, EI Segundo, CA, USA) was used to determine the quality of each spot. Raw data from ImaGene were submitted to Microarray Data Manager (He et al., 2010). In PRIMER6 data were log-transformed and hierarchically aggregated by gene name and category. Bray–Curtis similarity indices on log-transformed data were used to calculate distance matrices (Clarke, 1993). Similarity percentage analysis was used to identify genes and gene categories that discriminate between auriferous and non-auriferous soils (P<0.1; Clarke and Warwick, 2001).

Geochemical characterisation

After homogenisation, 0.5 g of each soil was microwave digested in concentrated aqua regia. Concentrations of major metals were determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (Spectro ARCOS SOP, Kleve, Germany); minor- and trace metals and metalloids were determined by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (Agilent 7500ce, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Total C and N were determined by high-temperature combustion (Formacs analyser; Skalar Inc., Breda, The Netherlands); electrical conductivity (E.C.) and pH were measured in 1:5 soil to water extracts. Location coordinates, geogenic factors and geochemical data and detection limits are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Data (except pH) were log transformed to remove skew. The data were normalised and similarity matrices based on Euclidean distances were generated. Physiochemical parameters were categorised into seven groups, including solution parameters (E.C. and pH) and six groups based on a modified Goldschmidt element classification (Goldschmidt, 1954; McQueen, 2008): Biophile- (Ctot, Ntot, P and S), calcophile- (Cu, Ga, Ge, Sn and Zn), Au-pathfinder- (Ag, As, Au, Bi, Mo, Pb, Se and W), lithophile- (Al, Ca, Cr, K, Mg, Na, Nb, Sc, Sr, Th, U and V), rare earth (Ce, Dy, Er, Eu, Gd, Ho, La, Lu, Nd, Pr, Sm, Tb, Tm, Y and Yb) and siderophile- (Fe, Co, Mn, Ni and Os) elements. PERMANOVA combined with CAP analyses were used to test the effects of underlying Au deposits, lithology, soil horizon and landform on geochemical parameters. Significant individual parameters are shown as vector overlays in CAP plots.

Results

Soil geochemistry

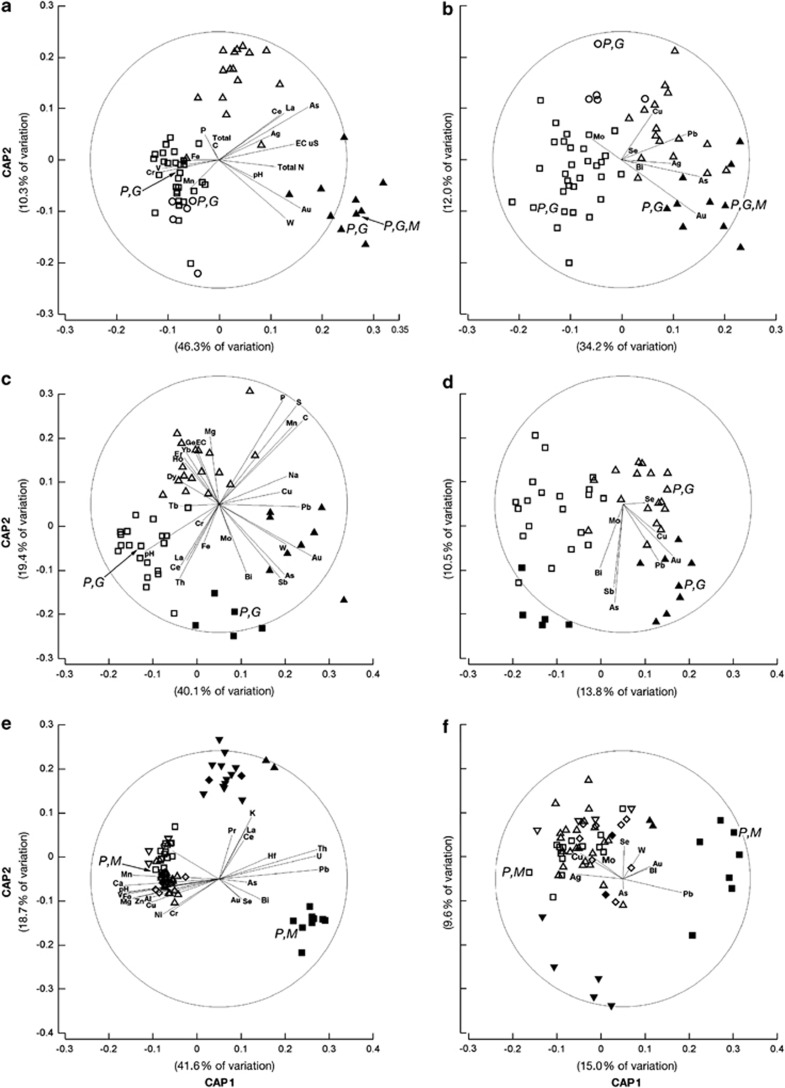

Geochemical data demonstrated highly significant (P<0.001) associations between element groupings, their distribution and geogenic factors (Table 1). CAP analyses across sites, showed that the a priori classification of elements produced a highly significant differentiation (P<0.001; Supplementary Figure S1). Distribution of elements was controlled by geogenic factors (P<0.05; PERMANOVA), as reflected in CV(√) values (Table 1; Anderson et al., 2008). At Old Pirate, the concentration of elements in soils was strongly linked to the underlying Au deposit and landform (P<0.05, Table 1), and a significant interactive effect between these parameters was observed (Table 1). In Tomakin, the element distributions differed with respect to the Au deposit and soil horizon (P<0.001; Table 1). At Wildcat and Humpback the dominant factor controlling the element distribution was lithology (P<0.001), with underlying Au deposit and landform displaying secondary influences (Table 1). CAP analyses revealed highly significant (P=0.001) separation according to geogenic factors. Canonical correlations were high (δ1>0.95; δ2>0.86), and canonical axes (CAs) 1 and 2 accounted for >40% and 10–20% of variation, respectively (Figures 2a).

Table 1. Results of PERMANOVA testing of the influence of the factors underlying Au deposit, soil horizon, landform and lithology on microbial communities and geochemical parameters at the study sites.

| Community structure | Bacteria (√) CVf | Pseudo-F | P | Fungi (√) CV | Pseudo-F | P | Archaea (√) CV | Pseudo-F | P | Geochemistry (√) CV | Pseudo-F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Pirate | ||||||||||||

| underlying D | 5.1g | 1.5 | 0.09 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 0.1 | −10.65 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 2.47 | 2.6 | 0.04 |

| RL | 8.0 | 2.6 | 0.0002 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 0.05 | 12.27 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 2.67 | 3.1 | 0.008 |

| D × RLa | 7.4 | 1.9 | 0.02 | 8.9 | 1.7 | 0.004 | 9.36 | 1.7 | 0.04 | 3.03 | 3.6 | 0.0006 |

| Residual | 23.1 | 39.2 | 40.49 | 6.93 | ||||||||

| Tomakin | ||||||||||||

| Underlying D | 18.5 | 4.6 | 0.0001 | 11.6 | 5.6 | 0.0001 | 10.8 | 1.6 | 0.04 | 3.67 | 7.3 | 0.0001 |

| SH | 13.6 | 2.9 | 0.0001 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 0.2 | −2.7 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 3.01 | 5.2 | 0.002 |

| D × SHb | 7.8 | 1.3 | 0.07 | −2.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | −11.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.45 | 2.4 | 0.06 |

| Residual | 41.7 | 23.3 | 59.9 | 6.31 | ||||||||

| Wildcat/Humpback | ||||||||||||

| Underlying D | −7.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 0.09 | 24.5 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 2.54 | 2.8 | 0.03 |

| L | 10.6 | 1.8 | 0.03 | 15.8 | 3.8 | 0.0001 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 5.21 | 14.0 | 0.0001 |

| RL | 9.7 | 1.3 | 0.07 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 0.05 | 18.0 | 1.6 | 0.07 | 1.69 | 1.6 | 0.08 |

| D × Lc | 5.7 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 10.3 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.41 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| D × RL | −11.0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 12.5 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.23 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| L × RLd | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 11.0 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 23.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 2.49 | 6.2 | 0.07 |

| D × L × RLe | −19.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | −14.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | Undetermined | 1.40 | 1.1 | 0.3 | ||

| Residual | 42.4 | 40.0 | 54.7 | 5.65 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: D, deposit; L, lithology ; PERMANOVA, permutational multivariate analysis of variance; RL, regolith landform; SH, soil horizon.

Interactive effect of underlying D and RL.

Interactive effect of underlying D and SH.

Interactive effect of underlying D and L.

Interactive effect of L and RL.

Interactive effect of underlying D, L and RL.

(√)CV is the square root of the component of variation, which is a data set dependent measure of the effect of size in units of the community dissimilarities (that is, increasing positive values); negative values indicate zero components (Anderson et al., 2008).

Significance level to assess the criteria was P<0.1 (in bold).

Figure 2.

Ordination plots of the first two CAs produced by CAP comparing geochemical (a, c and e) and geomicrobial data (b, d and f) of 62 Old Pirate-, 50 Tomakin Park, 75 Humpback and Wildcat sample sites from different geogenic settings. Old Pirate, a and b: (▴) auriferous, erosional; (Δ) non-auriferous, erosional; (□) non-auriferous, collovial; (○) non-auriferous alluvial; Tomakin Park c and d: (▴) auriferous, Ah-horizon; (Δ) non-auriferous, Ah-horizon; (▪) auriferous, B-horizon (□) non-auriferous, B-horizon; Humpback and Wildcat, e and f: (▪) granitic, erosional (▴) granitic, colluvial; (▾) granitic, depositional;(♦) granitic, alluvial; (□) mafic, erosional; (Δ) mafic, colluvial; (□) mafic, depositional; and (⋄) mafic, alluvial. Vectors of Spearman's correlations of the selected elements species with CAs are overlain; samples marked with M, P and G were used for microcosm experiments, PhyloChip and GeoChip analyses, respectively.

M-TRFLP—fingerprinting of microbial communities in field soils

Significant links existed between geogenic factors and bacterial and fungal communities at all sites (Mantel coefficients 0.3; P<0.05). At Old Pirate, the bacterial community composition varied with landform (√CV=8.0; P<0.001) and underlying Au deposit (√CV=5.1; P<0.1), and these factors were interactive (√CV=7.4; P=0.02; Table 1). Similarly, soil fungal and archaeal communities varied across landforms, but not with the underlying Au deposit (P<0.05). An interactive effect (P<0.05) of landform and Au deposit was observed (Table 1). CAP showed that bacterial and fungal communities were strongly separated between auriferous and non-auriferous soils (P<0.001; Figure 2b; Supplementary Figure S2A). Canonical correlation coefficients were high (δ1=0.91; δ2=0.70), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 34.2% and 12.0% of variation in the bacterial data set, respectively. To assess which geochemical parameters were linked to these variations, influences of each element group were evaluated using marginal testing in the distance based linear modeling (DSTLM) routine (Anderson et al., 2008). Individually, all groups of parameters had a significant relationship with bacterial and fungal data sets. Solution parameters (pH and E.C.), and biophile-, lithophile- and siderophile major elements displayed the strongest relationships (Table 2). Minor elements were also capable of explaining a proportion of the spread, for example, Au-pathfinder elements explained 21.6% of variation in the bacterial data set (Table 2).

Table 2. DISTLM of bacterial and fungal community diversities, based on M-TRFLP data vs geochemical parameters.

| Community | Solution (E. C., pH) | Biophile majors (C, N, P, S) | Lithophile majors (Al, Ca, K, Mg, Na) | Siderophile majors (Fe, Mn) | Calcophile minors (Cu, Ga, Ge, Sn, Zn) | Au-pathfinders minors (Ag, As, Au, Bi, Mo, Pb, Se, W) | Lithophile minors (Cr, Nb, Sc, Sn, Sr, Th, U, V) | REEs minor (Ce, Dy, Er, Eu, Gd, Ho, La, Lu, Nd, Pr, Sm, Tb, Tm, Y, Yb) | Siderophile-minor (Co, Ni, Os) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Pirate | |||||||||

| Bacteria Pseudo-F | 6.1 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| % of variation Fungi | 18.4/9.2 | 16.8/4.2 | 21.5/4.3 | 8.6/4.3 | 17.5/3.5 | 21.6/2.7 | 25.6/3.2 | 30.0/2.0 | 10.2/3.4 |

| Pseudo-F | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| % of variation | 10.2/5.1 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| Tomakin | |||||||||

| Bacteria Pseudo-F | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.2 |

| % of variationa Fungi | 8.8/4.4 | 18.0/4.5 | 20.5/4.1 | 10.0/5.0 | 18.0/3.6 | 24.8/3.1 | 26.4/ 3.3 | 42.0/2.8 | 13.2/4.4 |

| Pseudo-F | 2.3 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 3.6 |

| % of variation | 8.8/4.4 | 20.0/5.0 | 26.5/5.3 | 13.4/6.7 | 22.0/4.4 | 23.2/2.9 | 31.2/3.9 | 42.0/2.8 | 20.1/6.7 |

| Humpback | |||||||||

| Bacteria Pseudo-F | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | NS | 1.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| % of variation | 20.2/10.1 | 32.8/8.1 | 39/7.8 | 17.5/8.5 | NS | 68.6/7.3 | NS | NS | NS |

| Fungi Pseudo-F | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | NS | 1.6 |

| % of variation | 21.4/10.7 | 34.4/8.6 | 41.0/8.2 | 19.4/9.7 | 37.0/7.4 | 59.2/7.4 | 61.6/7.7 | NS | 28.2/9.4 |

| Wildcat | |||||||||

| Bacteria Pseudo-F | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | NS | 1.4 | NS | 1.4 | 1.3 | 2.1 |

| % of variation | 6.2/3.1 | 12.8/3.2 | 3.1 | NS | 2.7 | NS | 2.8 | 2.4 | 12.3/4.1 |

| Fungi Pseudo-F | 1.4 | 1,6 | 1.3 | NS | NS | NS | 1.3 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| % of variation | 5.8/2.9 | 13.2/3.3 | 2.6 | NS | NS | NS | 2.5 | 2.5 | 12.6/4.2 |

Abbreviations: E.C., electrical conductivity; DISTLM, distance-based linear regression modelling; M-TRFLP, multiplex-terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism; REE, rare earth elemant.

Bold font: significant <0.001; normal font: significant <0.05, italic font: significant <0.1; NS, not significant >0.1.

At Tomakin, the bacteria community varied with the underlying Au deposit (√CV=18.5; PERMANOVA P<0.001) and soil horizon (√CV=13.6; P<0.001). Fungal and archaeal communities varied with respect to the Au deposit (P<0.05), but not soil horizons (Table 1). Similarly, CAP analysis revealed a significant separation of bacterial and fungal communities (P<0.001; Figure 2d). Canonical correlations were high (δ1=0.91; δ2=0.80), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 13.8% and 10.5% of the variation, respectively. All groups of geochemical parameters showed significant relationships with bacterial and fungal data (Table 2), the strongest being displayed with siderophile-, biophile-, lithophile major elements and solution parameters (Table 2). Gold-pathfinder and rare earth elements were capable of explaining 24.8% and 42% of the variation, respectively (Table 2).

At Humpback and Wildcat, that is, the contiguous sites at Lawlers, bacterial community structures varied with underlying lithology (√CV=10.8, PERMANOVA P<0.05) and landform (√CV=9.7, PERMANOVA P<0.1; Table 1), but no links to the underlying Au deposit were detected (Table 1). Fungal communities varied with lithology, Au deposit and landform (P<0.1; Table 1); archaeal communities varied with landform (P=0.07; Table 1). Strong separation of bacterial and fungal communities occurred across sites with different lithologies (P<0.001) and landforms (P<0.001; Figure 2e, Supplementary Figure S2C). Canonical correlations were high (δ1=0.96; δ2=0.81), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 15.9% and 9.6% of variation in the bacterial data set, respectively. Because of the lithological differences between Wildcat and Humpback, assessment of associations of community structures with geochemical parameters was conducted separately. At Humpback, major elemental groups and Au-pathfinder elements showed significant relationships with bacterial communities (Table 2). Solution parameters displayed the strongest relationship with bacterial and fungal communities; 60–70% of variation could be explained by Au-pathfinder elements (Table 2). At Wildcat, all major and minor elements, except Au-pathfinder elements, were related to bacterial and fungal communities (Table 2).

M-TRFLP—fingerprinting of microbial communities in microcosms

To assess the effect of soluble Au(III) complexes on community compositions, soil microcosms were amended with up to 100 000 ng Au(III)-chloride g−1 soil d.w. Throughout the experiment the number of TRFs in unamended microcosms was 50–60 in Old Pirate soils, but decreased in Wildcat and Humpback microcosm soils (Supplementary Table S4). TRF numbers decreased for bacteria and archaea with increasing concentrations of soluble Au(III) complexes (Supplementary Table S4). In contrast, the numbers of fungal TRFs did not respond to increasing Au concentrations (Supplementary Table S4). Amendment with 100 000 ng Au(III)-chloride g−1 soil d.w. led to a reduction of TRFs by >90% hence these samples were excluded from statistical testing (Supplementary Table S4). The structure of the bacterial community was most strongly characterised by site (√CV=21.6), then Au-amendment (√CV=17.4) and then incubation time (√CV=11.2 (all P<0.001; Table 3). Interactive effects were significant, but weaker than the main effects of individual factors (Table 3). Fungal communities were similarly influenced, whereas the influence of these factors was weaker in archaeal communities (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of PERMANOVA testing Au amendment, IT and field site on the microbial community structure in microcosm experiments.

| Community structure | Bacteria | Fungi | Archaea | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

CV (√) |

Pseudo-F |

P |

CV (√) |

Pseudo-F |

P |

CV (√) |

Pseudo-F |

P |

| Au | 17.4 | 22.6 | 0.0001e | 14.4 | 6.0 | 0.0001 | 18.4 | 3.9 | 0.001 |

| SS | 21.6 | 15.0 | 0.0001 | 33.9 | 12.6 | 0.0001 | 20.5 | 3.1 | 0.007 |

| IT | 11.2 | 7.5 | 0.0001 | 11.0 | 3.1 | 0.0001 | 15.7 | 2.3 | 0.02 |

| Au × SSa | 15.2 | 6.4 | 0.0001 | 18.7 | 3.8 | 0.0001 | 17.6 | 1.8 | 0.04 |

| Au × ITb | 7.7 | 2.4 | 0.0001 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 0.0828 | −3.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| SS × ITc | 9.6 | 2.6 | 0.0004 | 13.5 | 2.0 | 0.0001 | −7.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Au × SS × ITd | 8.4 | 1.6 | 0.0025 | 13.4 | 1.5 | 0.0001 | ′ | 2.4 | 0.004 |

| Residual | 19.4 | 33.6 | 43.4 | ||||||

Abbreviations: AU, gold amendment; IT, incubation time; PERMANOVA, permutational multivariate analysis of variance; SS, sampling site.

Interactive effect of Au and SS.

Interactive effect of Au and IT.

Interactive effect of SS and IT.

Interactive effect of Au, SS and IT.

Significance level to assess the criteria was P<0.05 (in bold).

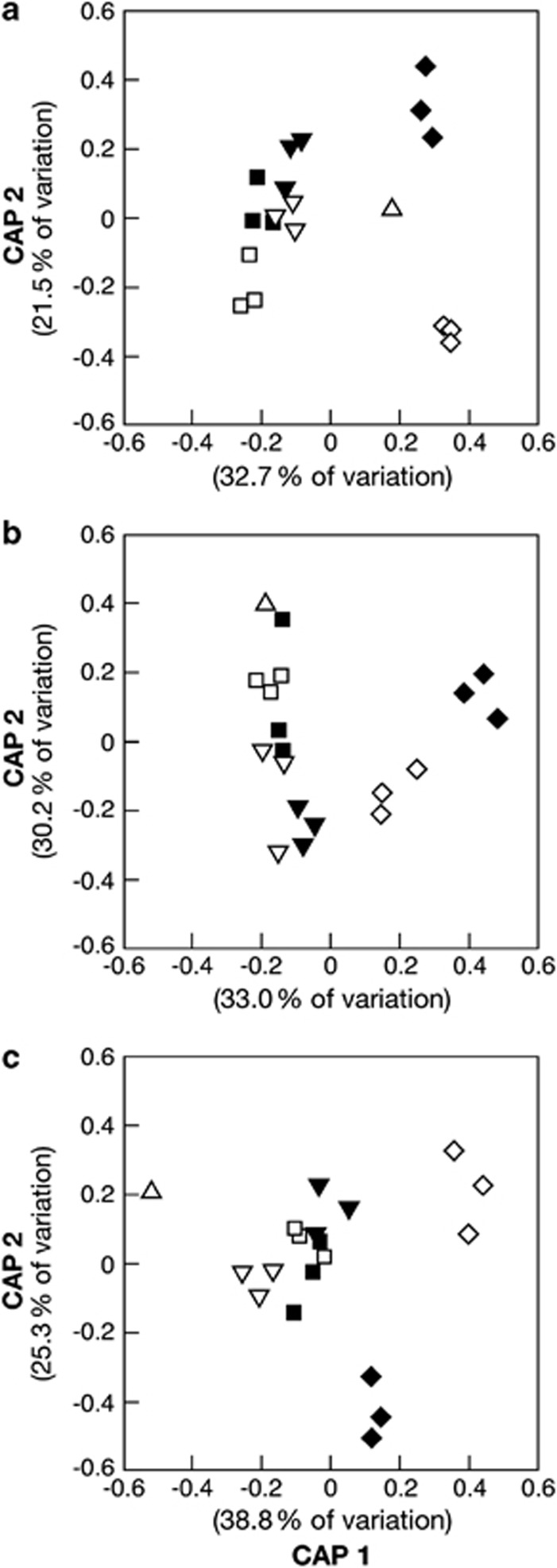

Whereas the amendment with 1000 and 100 000 ng Au(III)-chloride g−1 soil d.w. directly affected on the number of TRFs detected (Supplementary Table S4), the number of TRFs remained approximately constant with loads of 50 ng Au(III)-chloride g−1 soil d.w. Yet, the distribution of TRFs, that is, the species composition, varied significantly between amended and unamended samples after 30 days of incubation (Figure 3). In microcosms with Old Pirate samples, canonical correlations were high (δ1=0.99; δ2=0.96), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 32.1% and 21.5% of the variation in the bacterial data set, respectively (Figure 3a). In microcosms with Humpback samples, canonical correlations were high (δ1=0.99; δ2=0.9), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 33.2% and 30% of the variation in the bacterial data set, respectively (Figure 3b). In microcosms with Wildcat samples, canonical correlations were high (δ1=0.99; δ2=0.95), and CA1 and CA2 accounted for 38.1% and 25.3% of the variation in the bacterial data set, respectively (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Ordination plots of the first two CAs produced by CAP comparing bacterial TRLFP patters from microcosm soils amended with 50 ng g−1 AuCl4−(aq) (filled symbols) to unamended incubations (unfilled symbols after 0 (Δ) 2 (▾, ▿), 10 (▪, □) and 30 (♦, ⋄) days of incubation with samples from Old Pirate (a), Humpback (b) and Wildcat (c).

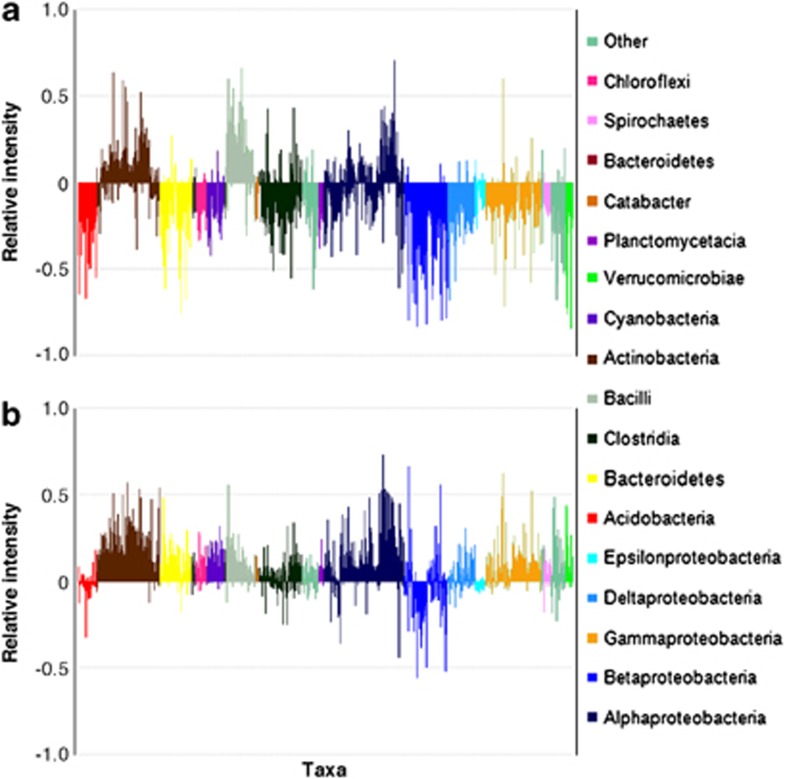

PhyloChip analyses of bacterial communities

PhyloChip microarrays were used to compare bacterial communities across representative auriferous and non-auriferous samples. Combined across all samples 42 phyla, 77 classes, 146 orders and 222 families were detected. In total, between 957 and 1678 taxa were observed in individual samples, of which 628 were shared across sites (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Venn diagram of total detected and shared taxa (a), and distribution of major phyla (b), at the in depth Old Pirate, Tomakin Park, Humpback and Wildcat sampling sites; with classes shown for Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, phyla with <1% coverage are aggregated into other. PlyloChip data with presence indicated by pf>0.9.

To assess which taxa dominated communities, the top 500 probe-intensity score data for each sample were used. Proteobacteria (34.4–49.8%), Firmicutes (8.4–21.8%), Actinobacteria (11.1–23.0%), Acidobacteria (1.9–5.8%) and Cyanobacteria (0.6–4.8%) were dominant in all samples (Figure 4b). Sphingobacteria, Verrucomicrobiae, Anaerolineae, Planctomycetacia, Catabacter, Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes and Chloroflexi each contributed between 0.6% and 1.8% to the composition of bacterial communities (Figure 4b). Within the Proteobacteria, most taxa were in the Alpha-proteobacteria class, consisting of 12–26% of array hits (Figure 4b). At Old Pirate the abundance of Alpha-proteobacteria, especially Sphingomonadales, and Firmicutes (Bacilli) was significantly higher in auriferous soils; these taxa explained >30% of the dissimilarity to non-auriferous soils (Supplementary Table S5). Beta- and Epsilon-proteobacteria and Acidobacteria were less abundant in auriferous soils; differences in these taxa explained 20% of dissimilarities (Supplementary Table S5). Similar results were obtained at Tomakin, where Actinobacteria, Alpha-proteobacteria and Bacilli were more abundant, and Beta- and Epsilon-proteobacteria and Acidobacteria were less abundant in auriferous soils (Supplementary Table S5). At Wildcat and Humpback sites, the strongest effect on microbial communities was lithology; hence two auriferous soils from erosional zones were analysed. At Wildcat, Actinobacteria, Beta- and Gamma-proteobacteria were more abundant and contributed ∼37% to dissimilarity to Humpback soil. Humpback soils were rich in Cyanobacteria explaining 18% of dissimilarities (Supplementary Table S5). Collective analysis across all samples showed that a ‘core community' of 50 taxa occurred only in auriferous soils (Supplementary Table S6). In all, 13 of these 50 taxa are among the 500 highest ranking taxa. Organisms hybridising to C. metallidurans probes occurred in auriferous Tomakin-, Wildcat- and Humpback soils and all Old Pirate soils.

In microcosms incubated for 10 days with 1000 ng g−1 d.w. soil of AuCl4− Actinobacteria and Bacilli were more, Acidobacteria, Clostridia, Beta- and Gamma-, Delta- and Epsilonproteobacteria were less abundant compared with unamended controls (Figure 5a, Supplementary Table S7). In microcosms incubated for 30 days with 50 ng g−1 d.w. soil of AuCl4-, Alpha-proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Bacilli were more, and Acidobacteria and Beta-proteobacteria were less abundant (Figure 5b). The Sphingomonads, a member of the Alphaproteobacteria, were enriched in Au-amended samples (Figures 5a and b).

Figure 5.

Plots showing relative differences of taxa observed from Phylochip data of Au-amended and -unamended microcosm experiments with soils samples from Old Pirate. (a) Differences observed after 10 days of incubation with 1000 ng g−1 AuCl4−(aq) g−1 d.w. soil; (b) Differences observed after 10 days of incubation with 50 ng g−1 AuCl4− g−1 d.w. soil.

Geochip-analysis of functional potential

The composition of functional genes associated with geochemical cycling and metal resistance varied between the auriferous and non-auriferous soils from Old Pirate and Tomakin (Figure 6a). Gene families associated with the degradation/transformation of organic contaminants (33.1%) and for metal resistance/reduction (18.5%) constituted the majority of genes detected (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Distribution of major gene categories (a) and metal reduction/detoxification genes (b) in key samples from Old Pirate and Tomakin Park determined by GeoChip analysis.

At Old Pirate and Tomakin, 1015 and 908 metal-resistance/reduction genes were detected in auriferous soil compared with 872 and 843 in non-auriferous soils, respectively (Figure 6b). In particular, Cu-, Cr- and As-detoxification genes were present in higher abundances (Figure 6b). At Old Pirate, 4 of 10 genes contributing most to the differences (P<0.05) between communities in auriferous and non-auriferous soils were metal-resistance genes: chrA, czcD, copA and zntA, which are involved in Cr-, Cd-Zn-Co-, Cu-Zn- transport and detoxification, respectively (Supplementary Table S8). At Tomakin, variation in the abundances of the copA gene was most strongly linked to separation between auriferous and non-auriferous soils, (Supplementary Table S9). Across all sites, 233 genes occurred only in auriferous soils. Of these, 69 are metal-resistance/reduction genes, and 19 of these are known to be involved in Cu resistance (Supplementary Table S10). In particular, genes that hybridised with the metal-resistance genes copA, chrA and czcA of the aurophillic bacterium C. metallidurans CH34 occurred only in auriferous soils (Supplementary Table S10).

Discussion

Our results showed that geogenic factors and associated geochemical parameters are fundamental determinants of microbial communities in naturally metal-rich soils. In addition to affecting the phylogenetic structure of soil microbial communities, geogenic factors also affected the community at a functional level. Phylogenetically, communities primarily differed across landforms (Old Pirate, Humpback and Wildcat), lithology (Humpback and Wildcat) and with underlying Au deposits (Old Pirate and Tomakin). Lithology and landform have long been recognised as primary drivers of soil formation processes, soil geochemistry, depth of weathering and the biogeographical distribution of plant communities (Jenny, 1941; Viles et al., 2008). It has been hypothesised that these factors also influence microbial community composition and function (for example, Viles, 2011, in press). However, in studies spanning both wide (France and California), and narrow geographic ranges (for example, glacier forefields) no significant links of communities to lithologies and landforms have been detected (Castellanos et al., 2009; Dequiedt et al., 2009; Lazzaro et al., 2009; Drenovsky et al., 2010). In these studies, factors linked to landuse (for example, farming and forestry) and climatic conditions, were dominant. Particularly in Europe this may be the result of permanent human settlement, with its influence on landuse for forestry, intensive agriculture, industry and recreation. In Australia the history of such influences is shorter, and the study sites have not been subjected to intense agriculture or forestry, hence geogenic drivers have not been masked by the shorter-term influences. This was also observed in two other Australian studies, which have shown that soil surface geomorphology and the presence of buried mineralisation influenced resident microbial communities (Mele et al., 2010; Wakelin et al., 2012a). A study by Wagai et al. (2011) has shown that soil microbial communities in Bornean tropical forests were strongly influenced by the underlying parent material; here the influence occurred either directly via soil geochemistry or indirectly via floristic expression.

Our study points to a stronger influence of soil metal contents on microbial communities in natural metal-rich soils than previously reported (for example, Duxbury and Bicknell, 1983). There may be several explanations for this observation. These are related to the long formation history of metal-rich soils used in this study, which controls the speciation and hence biological activity of mobile metals, the low organic matter contents and the solution parameters. Geogenic factors have had more time to express their influences on the geochemistry of many Australian landscapes compared with those in Europe or North America. At our study sites, the long weathering history led to the development of deeply weathered profiles and mature soils in landscape settings that are Tertiary to Permian. There the landscapes are comparatively young, with ‘new' landforms derived from extensive Upper Pleistocene glaciations overlying ‘fresh' rocks.

Owing to the long weathering history metals that are commonly assumed to be immobile, for example, Au, As, Pb, Ag, Cd, Cu, Zn, Ni and U, are highly mobile and hence bioavailable in mature Australian soils, which affects microbial communities (Aspandiar et al., 2008). Studies on soils with high C contents have shown that differences in soil organic matter quality are strong drivers of difference in microbial communities (for example, Torsvik and Øvreås, 2002). This may mask the influences of mobile metals, because soil organic matter displays strong metal sorption capacities, which decreases the mobility and bioavailability of mobile metals (Aspandiar et al., 2008). The low organic matter contents of our soils, and those studied by Wakelin et al. (2012a), may have increased metal mobility. At all sites, the influence of soil-pH and E.C. on microbial community compositions was greater than that to metal contents. This shows that solutions, which directly interact with the cell surfaces, have most immediate influence on microbial communities. Solution composition of are the result of interactions between inorganic and organic parent material, biota and water. Solution parameters reflect this and the mobility of metals (Aspandiar et al., 2008): E.C. correlates to the concentrations of major mobile elements, for example, Na, K, Ca, Mg, and S; pH correlates positively to trace metal contents, for example, Au, As and W at Old Pirate, and Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Zn and rare earth elements at Humpback. Hence, in the low C soil, mobile metals in solutions, whose composition is controlled by geogenic factors, can have a short-term impact on soil microbial communities, as demonstrated in the Au-amended microcosms.

Communities in auriferous soils contain more unique taxa and greater abundances of metal-resistance genes (Supplementary Table S6; Supplementary Table S10). This suggests that evolutionary pressures, possibly associated with low C content and elevated concentrations of mobile metals were involved in selecting for specialised communities. Alpha-proteobacteria, especially Sphingomonas spp., Actinobacteria and Bacilli were enriched in auriferous soils and Au-amended microcosms. In contrast, studies conducted in metal-polluted soils have often found higher abundances of Beta-proteobacteria; this was not observed here or by Wakelin et al. (2012b). This may be linked to the low C and N contents of studied soils, as Alpha-proteobacteria have a high proportion of genera that are phototrophic and/or are capable of N fixation, making them ideally suited to this low C and N habitat.

Metal-driven selection may explain the higher abundances of Sphingomonas spp. and taxa/metal-resistance genes related to C. metallidurans in auriferous soil. Sphingomonas are Gram-negative aerobic bacteria that are ubiquitous in soils and have a wide physiological tolerance to Cu and other metals (White et al., 1996). The occurrence of taxa related to C. metallidurans may be even more specifically linked to elevated concentrations of mobile Au, as C. metallidurans reductively precipitates toxic Au(I/III) complexes from solution via Au-regulated gene expression (Reith et al., 2009). Recent studies using transcriptome microarrays have shown that genes in C. metallidurans CH34 assumed to be specific to Cu resistance, that is, cup/cop (cupCAR) and (copVTMKNSRABC-DIJGFLQHE), were upregulated with Au(III) complexes at concentrations far below those where Cu regulation occurs (Reith et al., 2009). In particular, the Cutransporting P-type ATPase copA was strongly upregulated in the presence of Au(III) complexes, suggesting its involvement in their detoxification (Reith et al., 2009). However, Cu is not enriched in the auriferous soils at Old Pirate or Tomakin (this study; Reith et al., 2005), suggesting an influence of mobile Au complexes on the abundance of copA genes.

Conclusions

The microbial ecology of soils is strongly influenced by geogenic factors. Phylogenetic structure, especially bacterial, is strongly linked to lithology, presence underlying deposits and landforms, which control the geochemical make-up these soils. Furthermore, geochemical properties select for communities enriched with the functional potential to deal with elevated concentration of toxic metals. In particular, abundances of Alpha-proteobacteria, especially Sphingomonas spp. and Firmicutes (Bacillus spp.) were higher in auriferous compared with non-auriferous soils.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Australian Research Council (LP100200212 to FR), CSIRO Land and Water, The University of Adelaide, Newmont Exploration Pty Ltd, Barrick Gold of Australia Limited, Institute for Mineral and Energy Resources and the Centre for Tectonics, Resources and Exploration (TRAX no. 214), US Department Energy (DE-AC02-5CH11231 and DE-SC0004601). We thank L Fairbrother, C Wright for assistance with analyses, the editor IM Head and the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abaye DA, Lawlor K, Hirsch PR, Brookes PC. Changes in the microbial community of an arable soil caused by long-term metal contamination. Europ J Soil Sci. 2005;56:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Martinez V, Dowd S, Sun Y, Allen V. Tag-encoded pyrosequencing analysis of bacterial diversity in a single soil type as affected by management and land use. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40:2762–2770. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Gorley RN, Clarke KR. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER – Guide to software and statistical methods. Primer-E Ltd: Plymouth, UK; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aspandiar MF, Anand RR, Gray DJ.2008. Geochemical dispersion mechanisms through transported cover: implications for mineral exploration in Australia. Cooperative Research Centre for Landscape Evolution and Mineral Exploration, Open File Rep 246. Wembley West, Australia.

- Bååth E. Effects of heavy metals in soil on microbial processes and populations (a review) Water, Air, Soil Pol. 1989;47:335–379. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BJ, Banfield JF. Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2003;44:139–152. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JR, Curtis JT. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monograph. 1957;27:325–349. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie EL, DeSantis TZ, Joyner DC, Baek SM, Larsen JT, Andersen GL, et al. Application of a high-density oligonucleotide microarray approach to study bacterial population dynamics during uranium reduction and reoxidation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:6288–6298. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos T, Dohrmann AB, Imfeld G, Baumgarte S, Tebbe CC. Search of environmental descriptors to explain the variability of bacterial diversity from maize rhizospheres across a regional scale. Europ. J Soil Biol. 2009;45:383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analysis of changes in community structure. Austral J Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR, Warwick RM. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation. Primer-E Ltd: Plymouth, UK; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Denef VJ, Mueller RS, Banfield JF. AMD biofilms: using model communities to study microbial evolution and ecological complexity in nature. ISME J. 2010;4:599–610. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequiedt S, Thioulouse J, Jolivet C, Saby NPA, Lelievre M, Maron PA, et al. Biogeographical patterns of soil bacterial communities. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2009;1:251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis TZ, Brodie EL, Moberg JP, Zubieta IX, Piceno YM, Andersen GL. High density universal 16S rRNA microarray analysis reveals broader diversity than typical clone library when sampling the environment. Microb Ecol. 2007;53:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenovsky RE, Steenwerth KL, Jackson LE, Scow KM. Land use and climatic factors structure regional patterns in soil microbial communities. Glob Ecol Biogeo. 2010;19:27–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury T, Bicknell B. Metal-tolerant bacterial populations from natural and metal-polluted soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1983;15:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507535103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt VM. Geochemistry. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Deng Y, Van Nostand JD, Tu Q, Xu M, Hemme CL, et al. Geochip 3.0 as a high-throughput tool for analyzing microbial community composition, structure and functional activity. ISME J. 2010;4:1–13. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Qi HY, Zeng JH, Zhang HX. Bacterial diversity in soils around a lead and zinc mine. J Environ Sci-China. 2007;19:74–79. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(07)60012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbell RF.2002The Australian Soil Classification(Revised ed.)CSIRO Publishing Collingwood: Australia [Google Scholar]

- Jenny H. Factors of Soil Formation: A System of Quantitative Pedology. McCraw-Hill: New York, USA; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Kock D, Schippers A. Quantitative microbial community analysis of three different sulfidic mine tailing dumps generating acid drainage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5211–5219. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00649-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber CL, Strickland MS, Bradford MA, Fierer N. The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land-use types. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40:2407–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro A, Abegg C, Zeyer J. Bacterial community structure of glacier forefields on siliceous and calcareous bedrock. Europ J Soil Sci. 2009;60:860–870. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen KG.2008Regolith geochemistryIn: Scott KM, Pain CF (eds).Regolith Science CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia; 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mele P, Sawbridge T, Hayden H, Methe B, Stockwell T, et al. 2010. How does surface soil geomorphology and land-use influence the soil microbial ecosystems in south eastern Australia. Insights gained from DNA sequencing of the soil metagenome. Proceed. 19th World Congr. Soil Sci., Symposium 1.2.2, p. 12–15.

- Pain CF.2008Regolith description and mappingIn: Scott KM, Pain CF (eds).Regolith Science CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia; 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Reith F, Etschmann B, Grosse C, Moors H, Benotmane MA, Monsieurs P, et al. Mechanisms of gold biomineralization in the bacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:17757–17762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904583106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith F, McPhail DC. Effect of resident microbiota on the solubilization of gold in soil from the Tomakin Park Gold Mine, New South Wales, Australia. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;70:1421–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Reith F, McPhail DC, Christy AG. Bacillus cereus, gold and associated elements in soil and regolith samples from Tomakin Park Gold Mine in south-eastern New South Wales, Australia. J Geochem Explor. 2005;85:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Reith F, Rogers SL. Assessment of bacterial communities in auriferous and non-auriferous soils using genetic and functional fingerprinting. Geomicrobiol J. 2008;25:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Reith F, Rogers SL, McPhail DC, Webb D. Biomineralization of gold: biofilms on bacterioform gold. Science. 2006;313:233–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1125878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz MC, Phillippy AM, Gajer P, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Ravel J. Integrated microbial survey analysis of prokaryotic communities for the PhyloChip microarray. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5636–5638. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00303-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BK, Nazaries L, Munro S, Anderson IC, Campbell CD. Use of multiplex terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism for rapid and simultaneous analysis of different components of the soil microbial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7278–7285. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00510-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsvik V, Øvreås L. Microbial diversity and function in soil; from genes to ecosystems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;3:240–245. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viles HA.2011Microbial geomorphology: a neglected link between life and landscape Geomorphologydoi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.03.021 [DOI]

- Viles HA, Naylor LA, Carter NEA, Chaput D. Biogeomorphological disturbance regimes: progress in linking ecological and geomorphological systems. Earth Surf Process Landforms. 2008;33:1419–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Wagai R, Kitayama K, Satomura T, Fujinuma R, Balser T. Interactive influences of climate and parent material on soil microbial community structure in Bornean tropical foresy ecosystems. Ecol Res. 2011;26:627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin SA, Macdonald LM, Rogers SL, Gregg AL, Bolger TP, Baldock JA. Habitat selective factors influencing the structural composition and functional capacity of microbial communities in agricultural soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40:803–813. [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin SA, Anand RR, Reith F, Gregg AL, Noble RRP, Goldfarb KC, et al. Bacterial communities associated with a mineral weathering profile at a sulphidic mine tailings dump in arid Western Australia. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012a;79:298–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin SA, Anand RR, Reith F, Macfarlane C, Rogers S. Biogeochemical surface expression over a deep, overburden-covered VMS mineralization. J Geochem Explor. 2012b;112:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin SA, Chu GX, Broos K, Clarke KR, Liang YC, McLaughlin MJ. Structural and functional response of soil microbiota to addition of plant substrate are moderated by soil Cu levels. Biol Fert Soils. 2010a;46:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Wakelin SA, Chu GX, Lardner R, Liang YC, McLaughlin MJ. A single application of Cu to field soil has long-term effects on bacterial community structure, diversity, and soil processes. Pedobiologica. 2010b;53:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- White DC, Sutton SD, Ringelberg DB. The genus Sphingomonas:physiology and ecology. Curr Opin Biotechn. 1996;7:301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.