Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a complex genetic disorder that is associated with environmental risk factors and aging. Vertebrate genetic models, especially mice, have aided the study of autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive PD. Mice are capable of showing a broad range of phenotypes and, coupled with their conserved genetic and anatomical structures, provide unparalleled molecular and pathological tools to model human disease. These models used in combination with aging and PD-associated toxins have expanded our understanding of PD pathogenesis. Attempts to refine PD animal models using conditional approaches have yielded in vivo nigrostriatal degeneration that is instructive in ordering pathogenic signaling and in developing therapeutic strategies to cure or halt the disease. Here, we provide an overview of the generation and characterization of transgenic and knockout mice used to study PD followed by a review of the molecular insights that have been gleaned from current PD mouse models. Finally, potential approaches to refine and improve current models are discussed.

Behavioral impairments, α-synuclein aggregation and degeneration of dopamine neurons have been reproduced in some animal models of PD. Additional models that properly recapitulate dopaminergic neurodegeneration are needed.

P arkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder with a characteristic degeneration of dopamine (DA)–producing neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) (Dauer and Przedborski 2003). Surviving DA neurons of the SN and neurons in other affected areas carry α-synuclein (α-syn)–containing Lewy bodies, implying a pathological role for α-syn in PD progression (Spillantini et al. 1997). Despite the relatively selective loss of DA neurons in the SN that accounts for the underlying motor deficit in PD, patients commonly also develop nonmotor symptoms with substantial neurodegeneration and Lewy body formation in broad brain regions (Churchyard and Lees 1997; Chaudhuri et al. 2007). DA supplementation alleviates the major motor symptoms in PD (Savitt et al. 2006), but its effectiveness declines over time. Unfortunately, no effective treatments are available to stop or prevent the disease progression because of a poor understanding of the molecular mechanisms of selective and progressive neurodegeneration in PD.

In rare, inherited PD, mutations in several genes cause PD pathologies that are often indistinguishable from sporadic PD (Savitt et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2011). The identification of PD-linked genes has prompted focused studies of molecular signals that cause PD. Moreover, PD genes provide a rational basis to model the disease in cells or animals by genetic manipulations.

Animal models that faithfully recapitulate the characteristic neurodegeneration and pathological hallmarks of PD are necessary to validate pathogenic molecular pathways in vivo and also test therapeutic strategies in more controlled physiological systems. Many genetic PD models have been informative in understanding molecular pathways and pathological changes that may be PD-relevant (Dawson et al. 2010).

MODELING PD IN MICE: OVERVIEW ON THEIR GENERATION AND CHARACTERIZATION

Researchers generally prefer mouse models to simulate human genetic disorders because mice possess similar neuronal networks and disease-associated gene homologs (Waterston et al. 2002). The evolutionarily conserved neuronal networks and PD gene homologs indicate that findings in PD mouse models are likely to mirror the pathological events occurring in human PD. The ease of and advances in genetic manipulation have enabled the generation and refinement of genetic mouse models (Tables 1 and 2). These include conventional transgenic approaches in which a gene is overexpressed under the control of a promoter that drives expression in the brain. Promoters can be selected that provide tissue-specific or cell-type-specific expression. Recent advances allow conditional temporal expression of a transgene in which a gene’s expression is controlled by a drug-based switch that allows temporal fine-tuning of the expression (Landel et al. 1990). One can also knock out (KO) a gene and knock in (KI) discrete mutations by homologous recombination (Capecchi 1989). The availability of inbred strains of mice with similar genetic backgrounds facilitates the comparison of control and genetically manipulated mice in the same genetic background. Moreover, the relatively long life span (2 yr) compared with simpler organisms offers the opportunity to assess pathological changes across the aging process, which is the single most prominent risk factor for PD in humans. Finally, the broad spectrum of phenotypic readout in mice better represents the complex characteristics of human PD (Rosenthal and Brown 2007).

Table 1.

Autosomal-dominant mouse models of PD

| Promoter | Transgene | Cell death | Motor deficits/ nigrostriatal dysfunction | Cellular abnormalities | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDGF-β | WT α-syn | No neurodegeneration | ↓ Rotarod performance (12 mo)/↓ TH and fiber density (STR) | Inclusion bodies (Ub, Syn +) | Masliah et al. 2000 |

| mThy-1 | A30P α-syn | Sensorimotor neuronal loss (brainstem and SC) | Severe leading to paralysis (8∼12 mo)/normal DA and metabolite levels | LB-like inclusion (fibril) | Neumann et al. 2002 |

| mPrP | A53T α-syn | Non-dopaminergic neuronal loss (red nuclei, brainstem, and SC) | Severe (12 mo)/normal DA levels, normal TH morphology | LB-like inclusion (fibril), mitochondrial dysfunction | Giasson et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2002; Gispert et al. 2003 |

| Rat TH (9 kb) | A30P/A53T α-syn | Progressive DA neuronal loss | ↓ Locomotor activity (13–23 mo)/↓ DA and metabolites, TH axons beaded | No inclusion bodies, diffuse synuclein in DA neurons, ↑ presynaptic DAT | Richfield et al. 2002 |

| CamKII-tTA (tet-off) | WT α-syn, A53T α-syn | Trend for TH+ cell loss, degenerating cells in SN and hippocampus (WT), non-DA neuronal loss (A53T) | ↓ Rotarod performance and motor learning (WT)/normal DA levels (STR) | Condensed mitochondria and lipid droplets | Nuber et al. 2008 |

| BAC | LRRK2 R1441G | No | ↓ Rearing (12 mo)/↓ DA transmission (STR), ↓ fiber density (SNr), neurite fragmentation (STR) | ↑ Tau and phosphorylated tau | Li et al. 2009 |

| CamKII-tTA (tet-off) | LRRK2–WT/GS/KD | No | Normal | Golgi structure fragmentation | Wang et al. 2008; Lin et al. 2009 |

| Knockin | LRRK2-R1441C | No | ↓ Amphetamine-induced locomotor activity/normal DA levels (STR) | Altered D2 receptor activity | Tong and Shen 2009 |

Characterization of some of the autosomal-dominant mouse models.

Abbreviations: TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; STR, striatum; Ub, ubiquitin; SC, spinal cord; DA, dopamine; DAT, dopamine transporter; SNr, substantia nigra reticulata; KD, kinase dead; D2, dopamine subtype 2 receptor.

Table 2.

Autosomal-recessive mouse models of PD

| PD gene | Motor deficit | Electrophysiological/neurochemical dysfunction | Biochemical changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin | Declines in voluntary and amphetamine-induced activity, beam traversing, acoustic startle response | ↑ DA (STR, limbic); ↓ NE (OB, SC), ↓ striatal neuron excitability | ↓ DAT, VMAT2; ↑ reduced glutathione (STR); ↑ parkin substrates (STR, Vmb); ↓ mitochondrial and antioxidant proteins (Vmb) | Goldberg et al. 2003; Itier et al. 2003; Von Coelln et al. 2004 |

| DJ-1 | Age-dependent declines in locomotor activity, rearing, and tape removal test (11 mo) | ↑ DA re-uptake, DA content, and ↑ stimulated DA release (STR) | Normal amounts of TH, DAT, VMAT2 (STR), and oxidized proteins; ↓ mitochondrial peroxidase activity | Chen et al. 2005; Goldberg et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2005; Andres-Mateos et al. 2007 |

| PINK1 | Age-dependent impairment of spontaneous activity | ↓ Evoked DA release; ↓ DA content (STR) | ↑ Large mitochondria, mitochondrial respiration, ATP generation; ↓ aconitase activity (STR) | Gautier et al. 2008; Gispert et al. 2009; Kitada et al. 2009 |

Characterization of germline knockout of recessive PD genes including parkin, DJ-1, and PINK1.

Abbreviations: NE, Norepinephrine; OB, olfactory bulb; VMAT, vesicular monoamine transporter; Vmb, ventral midbrain.

GENETIC MOUSE MODEL TECHNIQUES

Transgenic Mouse Models

Even though “transgenic animal” defines a rather broad spectrum (Rulicke et al. 2007), it is commonly used to describe animals that overexpress a foreign protein. Transgenic technology has successfully modeled many human diseases in mice by introducing human disease genes or mutants (Rockenstein et al. 2007). For example, many neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and PD share a common etiology of aberrant protein accumulation and aggregation, and mice expressing disease proteins (i.e., amyloid-β in AD; expanded glutamine repeats in huntingtin in HD; α-syn in PD) in brain mirror human disease conditions and serve as instructive genetic models (Rockenstein et al. 2007).

The transgenic construct comprises structural elements and promoter sequences. Usually dominant mutants (i.e., A53T, A30P, and E46K for α-syn; G2019S and R1441C/G mutants for LRRK2) are preferred because the mode of inheritance supports a gain of toxicity or exaggeration of its endogenous function. For the induction of the transgene, the promoter directly governs expression levels, pattern, and timing. Considering the progressive feature of neurodegenerative diseases, the promoter for modeling the disorder should be constitutively active throughout the lifetime of mice and rather strong to induce sufficient levels of the transgene.

TET-OFF CONDITIONAL TRANSGENIC MODELS

A more advanced technique is the tetracycline (Tet)–regulated transgenic switch that uses two separate components acting in trans (i.e., responder component, tetP + transgene; activator or driver component, tissue-specific promoter + tTA) (Gossen and Bujard 1992). Tight regulation of the tet-promoter (tetP) by the Tet-regulated transcription activator (tTA) drives transgene expression. Therefore, expression of the transgene should follow the activity pattern of the promoter in the driver construct. The ability of tTA to change its conformation and affinity for tetP by doxycycline allows temporal on/off control of transgene induction (Gossen and Bujard 1992; Kistner et al. 1996; Sprengel and Hasan 2007). In addition to temporal and spatial regulation, this system offers amplification of tissue-specific promoter strength by the relaying action of tTA onto tetP, thus resulting in more robust induction of the transgene compared with that of conventional transgenesis, in which the transgene expression is driven by the upstream tissue-specific promoter alone (Bond et al. 2000). The potential refinement of previous unsatisfactory transgenic models by the use of the Tet-off genetic switch provides the possibility of creating mice that show appropriate pathologies. For instance, the development of Tet-off conditional PD mouse models expressing wild-type and mutant forms of α-syn may have a strong tendency for TH-positive neuron loss, particularly when the expression is turned on in adulthood. Moreover, conditional models allow the opportunity to determine whether behavioral and pathological changes are reversible when the offending protein expression is reduced or turned off (Dawson et al. 2010).

KO MODELS

Recessive genetic mutations seem to lead to PD pathogenesis via loss of function. The association of heterozygous mutations with increased susceptibility to develop PD supports the notion that autosomal-recessive PD genes exert protective roles in PD-related pathology. As such, targeted deletion of functionally important exons of the autosomal-recessive gene or introduction of premature termination should be able to simulate early-onset PD in genetic mouse models much in the same way that homozygous autosomal-recessive PD gene mutations cause PD in humans. However, germline deletion of parkin, PINK1, and DJ-1 has yielded mice with minimal phenotypes (Dawson et al. 2010). Even knocking out all three genes in the same mouse provided no substantial phenotype (Kitada et al. 2009). Most mouse models of recessive PD have adopted a conventional KO approach, and the lack of phenotypes and potential compensatory mechanisms preventing neurodegeneration make it necessary to use more sophisticated conditional models. The Cre–loxP–mediated conditional KO approach is widely used when embryonic lethality prevents studying deletion of a gene in adult animals. By using well-characterized tissue-specific Cre-expressing lines, exons or genes flanked by loxP sites in conditional mice can be deleted in desired tissues. Here, the promoter upstream of Cre governs the timing as well as the region(s) of gene deletion. Recent advances have coupled the Cre–loxP system to a tamoxifen-sensitive Cre (Cre-ER). Tamoxifen binding can activate an otherwise dormant Cre-ER, providing temporal regulation of gene deletion. Alternatively, viruses carrying a Cre expression cassette can provide the temporal and spatial resolution to delete genes from select brain regions at various ages. This approach was used successfully to create the first genetic model of PD that shows progressive degeneration of DA neurons by conditionally knocking out parkin in adult mice (Shin et al. 2011).

VIRUS-INDUCED MODELS

Stereotaxic viral injection is another tool that enables acute and robust induction of the transgene in desired regions of the brain. Different viral systems (e.g., lentivirus, recombinant adeno-associated virus [rAAV], and herpes simplex virus [HSV]) are available and can be chosen according to the gene structure and the purpose of experiments (Table 3). For instance, the rAAV system has the advantage of transducing broad regions of tissue. A single stereotaxic injection can transduce most DA neurons in the SN. Different rAAV serotypes can be used to transduce different cell types preferentially (e.g., AAV2 is more specific for neurons vs. glia; AAV1 and 5 are highly diffusible but not selective). A limitation of rAAV is that it has a packaging capacity of ∼4.7 kb, thus large genes cannot be efficiently packaged by rAAV. HSV, on the other hand, can package large genes such as LRRK2 and transduce neurons very efficiently. HSV also has the advantage of retrograde transport, in which HSV virus can be stereotaxically injected into the striatum, leading to efficient transduction of DA neurons in the SN (Lee et al. 2010). The ability of HSV to package large genes such as LRRK2 made possible the successful modeling of LRRK2-induced DAergic neuronal toxicity and further testing of potential kinase inhibitors in vivo (Lee et al. 2010). Notably, the successful expression of the transgene and PD modeling by viral approaches heavily depend on the quality and titer of virus particle. High titer and infectivity ensure success. Viruses can also be used to deliver short hairpin RNA to accomplish efficient gene knockdown in vivo. Moreover, using the Cre–loxP system, Cre-expressing viruses can acutely silence genes when injected into conditional KO mice that have loxP-flanked sites.

Table 3.

Viral models of PD

| Animal | Virus/injection | Nigrostriatal pathology | Biochemical changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL6 | HSV-LRRK2 (WT/G2019S)/striatal injection | DA neuronal loss (GS only) (4 wk) | ND | Lee et al. 2010 |

| Monkey; rat | rAAV (WT/A53T)/intranigral; Lenti virus (WT/A30P/A53T) | DA neuronal loss/DA loss/motor impairment (monkey, 16 wk) | Non-fibril inclusion | Lo Bianco et al. 2002; Kirik et al. 2003 |

| Parkinflox/flox | AAV-Cre/intranigral | DA neuronal loss (10 mo) | ↑ Parkin substrates; PGC1-α down-regulation | Shin et al. 2011 |

All virus-induced mouse models of PD listed in the table developed degeneration of DA neurons in SNpc. Successful application of acute PD gene delivery or deletion is summarized, including LRRK2, synuclein transgenic models, and the conditional parkin KO model.

Abbreviations: ND, No available data; PGC1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) coactivator-1.

CHARACTERIZATION OF PD MOUSE MODELS

Our understanding of PD has been advanced by an integrated approach of in vitro, cellular, and animal studies in connection with findings from clinical studies in PD patients (Moore et al. 2005). Moreover, validation of PD mouse models has relied on how faithfully they can recapitulate the major characteristic clinical and pathological features found in human PD. Animal models are reliable and have a predictive value only when they reproduce the abnormal phenotypical changes of human PD (Dawson et al. 2010). Several features characterize PD (Savitt et al. 2006), and various models show some but not all of the features of human PD.

Diverse approaches and tools used in human studies can similarly be applied to characterize animal models in detail. For example, application of new methods in expression profiling, proteomics, and metabolomics can be used for detailed characterization of PD mouse models, thus providing a global network assessment of pathogenic pathways in a controlled physiological environment with the same genetic background (Simunovic et al. 2009; Cloutier and Wellstead 2010).

WHAT WE HAVE LEARNED FROM PD MOUSE MODELS

α-Synuclein Transgenic PD Models

Familial mutations and elevated levels of α-syn due to multiplication increase α-syn’s tendency to form aggregates that correlates with the severity of pathology in PD (Polymeropoulos et al. 1997; Singleton et al. 2003). Haplosufficiency and a dominant mode of inheritance also support a toxic gain-of-function model for the α-syn pathogenesis theory. Interestingly, α-syn aggregation characterizes many disorders, designated as “α-synucleinopathies” (Dev et al. 2003). Thus, Lewy bodies or oligomer, proto-fibril, and fibril intermediates may contribute to progression of many neurological disorders through damage in different regions and types of cells depending on where α-syn aggregates. In this regard, mice expressing α-syn can be used to model α-synucleinopathy-induced neuronal degeneration.

Many transgenic lines have used pan-neuronal or DA-specific promoters to express α-syn wild type (WT) or mutants. Notably, the severity and age of onset of disease depend heavily on the promoter and levels of transgene expression. Many of the models show neurodegeneration and are instructive for studying the molecular mechanism by which α-syn aggregation and neurodegeneration occur in vivo. However, most of these models fail to show DA neuron loss, the key pathological feature of PD, although there are subtle functional abnormalities in the nigrostriatal system and neurodegeneration in other anatomical circuits (Fernagut and Chesselet 2004).

Among the many α-syn transgenic mice, the mouse prion promoter (mPrP) and A53T transgenic mice recapitulate most of the pathologies linked to α-synucleinopathies, including phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and aggregation of α-syn leading to progressive neurodegeneration (Giasson et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2002). Even though most of the neurodegeneration occurs in motor neurons, not in DA neurons, the study of α-syn-induced cell death pathways in these other neuronal systems may provide insight into mechanisms of α-syn-induced degeneration that has relevance for degeneration of DA neurons (Forno 1987; Churchyard and Lees 1997).

Because there is no obvious DA neuronal loss in most α-syn transgenic mice, mechanistic studies of DA neuronal death by α-syn have been aided through the study of the impact of α-syn expression following MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) intoxication (Song et al. 2004; Nieto et al. 2006). Mitochondrial dysfunction appears to be sufficient to induce α-syn aggregation and downstream toxicity for DA neuronal loss in MPTP mouse models. As expected, the DA neurons of α-syn transgenic mice show more sensitivity for mitochondrial toxins (Nieto et al. 2006). Interestingly, the DA neurons of α-syn knockouts are resistant to MPTP intoxication (Dauer et al. 2002), which is complemented by WT and mutant human α-syn, showing the requirement of α-syn aggregation for DA neuron loss downstream from mitochondrial dysfunction (Thomas et al. 2011). Conversely, α-syn transgenic mice display mitochondrial abnormalities in degenerating neurons (Martin et al. 2006).

The mechanism of α-syn-induced mitochondrial dysfunction might involve sequestration of mitochondrial proteins or yet-unidentified pathways (Olzscha et al. 2011). The dysfunction of mitochondria with α-syn aggregation may enhance the toxic aggregate formation in a feed-forward signal amplification manner. In this context, inhibition of either mitochondria damage or α-syn aggregation may halt or delay degenerative processes set in motion in PD animal models if restorative protective signaling pathways remain intact. The amelioration of progression of motor deficits in Tet-off α-syn transgenics by doxycycline-induced cessation of α-syn expression supports this notion (Nuber et al. 2008).

In addition to mitochondrial dysfunction in α-syn transgenic mice, one downstream consequence of α-syn aggregation is likely to be a DNA damage response, leading to cell death. MPTP toxicity for DA neurons is protected not only by α-syn deletion, but also by PARP1 deletion (Mandir et al. 1999). Because PARP1 overactivation upon DNA damage is sufficient to induce cell death (Koh et al. 2005), α-syn aggregation may induce toxicity by trapping and sequestering protein complexes that are important for the regulation of PARP1. Consistent with this notion is the observation that mice lacking PARP1 are dramatically resistant to MPTP intoxication (Mandir et al. 1999).

LRRK2 TRANSGENIC PD MODELS

Dominant mutations in LRRK2 are the most common cause of familial PD (Goldwurm et al. 2005). Structurally, LRRK2 is a very interesting protein, which has GTPase and kinase domains in addition to leucine-rich repeat domains, forming a large protein kinase. The aberrant kinase activity of LRRK2 by common mutations such as G2019S, R1441C, and R1441G is thought to be the culprit leading to DA neuron degeneration in PD (West et al. 2005, 2007). In this context, many groups have generated LRRK2-related PD mouse models expressing LRRK2 wild-type or PD-associated mutant LRRK2 to simulate aberrant kinase activity (Dawson et al. 2010). Despite several transgenic techniques for LRRK2-related PD modeling in mice (i.e., conventional, BAC transgenic, mutant LRRK2 KI, and tet-inducible transgenic), only one of the LRRK2 models reproduces age-dependent nigral DA neuron death (Ramonet et al. 2011). However, most LRRK2 transgenic animals manifest deficits in DA transmission and DA-responsive behavior. It will be of interest to determine whether environmental toxins or the combination with related genetic PD models leads to more robust phenotypes.

The pathogenesis of LRRK2 is likely to result from aberrant kinase activity and the resulting phosphorylation of substrates and misregulation of binding partners and regulators. Recent studies using HSV-LRRK2 G2019S viral-induced DA neurodegeneration models conclusively showed that aberrant kinase activity of LRRK2 G2019SS underlies DA neuronal degeneration and that inhibition of kinase activity by inhibitor of LRRK2 kinase activity is sufficient to suppress its toxic signaling (Lee et al. 2010). Given that kinase activity is important, the identification of physiological or aberrant phosphosubstrates would be quite instructive to further delineate the pathogenic signaling induced by LRRK2 mutations.

PARKIN GENETIC MODELS

Many groups have generated parkin KO mice to model PD due to parkin loss (Goldberg et al. 2003; Itier et al. 2003; Von Coelln et al. 2004). Initial characterization of parkin-null strains failed to see any signs of nigral DA neuronal death, although abnormal DA metabolism was noted. Interestingly, catecholaminergic neurons in LC regions of mice with parkin catalytic domain deletion degenerated with an accompanying deficit in the startle response (Von Coelln et al. 2004). Proteomic studies using parkin-null mice showed marked reduction of mitochondrial respiratory chain proteins and stress response proteins when compared with littermate controls. Moreover, immunoblot analysis showed that several parkin substrates (AIMP2, FBP1, and PARIS) accumulate especially in the ventral midbrain of parkin-null mice (Ko et al. 2005, 2006; Shin et al. 2011). These cellular changes may be responsible for subtle deficits in DA metabolism and behavior. Surprisingly, MPTP intoxication in parkin-null mice caused a similar level of DA neuronal toxicity compared with wild-type mice, although parkin overexpression provides protection against MPTP (Perez et al. 2005; Paterna et al. 2007; Thomas et al. 2007). A compensatory remodeling in parkin-deficient DA neurons may have complemented parkin-related protective roles against mitochondrial dysfunction.

A recent conditional parkin KO model develops DA neurodegeneration. Lentiviral-Cre nigral injection into adult parkinflox/flox mice causes acute parkin deletion and progressive nigral neuron death >10 mo after the gene deletion. There are pathogenic sequential events caused by accumulation of PARIS including PGC1-α down-regulation, and ultimately mitochondrial dysfunction (Shin et al. 2011). Considering many reports of parkin’s role in the mitochondria (Clark et al. 2006; Wild and Dikic 2010), the pathways revealed in this adult conditional parkin KO model may be quite relevant to PD pathogenesis and may represent a promising model to test new therapies.

PINK1 GENETIC MODELS

Two PINK1-targeted KOs (Kitada et al. 2007; Gispert et al. 2009) and shRNA-mediated knockdown models (Zhou et al. 2007) have been reported. In contrast to robust degenerative phenotypes and mitochondrial defects that have been observed in genetic fly models (Clark et al. 2006), PINK1 KO and knockdown mice failed to replicate these features. Nevertheless, subtle deficits of nigrostriatal DA transmission and accompanying mild mitochondrial abnormalities (i.e., impairment of mitochondrial respiration and electrochemical potential) were observed in PINK1 KO mice. One PINK1 KO model also shows mild, but significantly less DA content in the striatum and reduced spontaneous voluntary activities, which were age dependent (Gispert et al. 2009). The mild deficit in presynaptic function of PINK1 KO mice resembles that of several parkin KO mice.

Although loss of PINK1 kinase activity due to PD-associated mutations causes early-onset PD in humans, the lack of nigral neurodegeneration in KO models prevents further investigation of the role of physiological and pathophysiological PINK1 phosphosubstrate that may contribute to PD pathogenesis in vivo. Despite the lack of degeneration in the PINK1 KO mouse, there are, indeed, mild abnormalities in mitochondrial function in one of the PINK1 KO models. In this regard, attempts can be made to identify the downstream substrate responsible for the mitochondrial defect in PINK1-null mice.

DJ-1 GENETIC MODELS

Diverse biological roles for DJ-1 have been proposed from many cell-based studies. The results collectively emphasize DJ-1’s role as a redox-sensitive molecular chaperone that provides protection against cellular stresses (Moore et al. 2003). DJ-1 seems to function as an atypical peroxiredoxin-like p (Andres-Mateos et al. 2007). Despite its diverse involvement in cell-protective processes, DJ-1-null mice failed to display any overt signs of nigral neurodegeneration (Chen et al. 2005; Goldberg et al. 2005). Similarly to parkin and PINK1 KO mice, DJ-1 KO mice also develop mild deficits in DA neurotransmission and mitochondrial dysfunction even in the absence of DA neuron loss. Still, consistent with its protective role against stress, DA neurons with DJ-1 deletion show increased susceptibility for MPTP (Kim et al. 2005). Moreover, recent electrophysiological studies for DA neurons of DJ-1 KO mice showed elevated mitochondrial oxidant stress due to compromised uncoupling of mitochondria following basal pacemaking potential (Guzman et al. 2010). Although this altered mitochondrial potential and oxidative stress persist without DA neurodegeneration, these changes may predispose DA neurons so that additional hits such as MPTP or the aging processes surpass the threshold for cell death initiation in these neurons.

REFINEMENT OR REINVENTION OF PD ANIMAL MODELS OF DA NEURODEGENERATION

None of the current genetic mouse PD models recapitulates all of the features of PD. Additionally, only a few models develop mild DA neurodegeneration. The most parsimonious explanation for the lack of DA neurodegeneration in genetic PD mouse models is compensatory mechanisms that may result from adaptive changes during development, thus making it hard to observe the degenerative phenotype over the life span of mice. This kind of compensatory mechanism is prevalent in higher mammalian species and may be evolutionarily necessary for survival of a species against rather frequent spontaneous mutations in some essential genes (Gao and Zhang 2003). Presumably, similar compensatory pathways develop in familial human PD patients. The late onset and strong age association in human PD may support the successful makeover of genetic lesions by these adaptive remodeling mechanisms of DA neuron physiology. The successful modeling of DA neuron loss in lower genetic models such as Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans, in addition to viral-induced acute mouse models as well as adult conditional knockout of genes, is beginning to shed light on how the remarkable compensation in genetic mouse models can be overcome, thus creating faithful recapitulation of key PD features in the lifetime of mice.

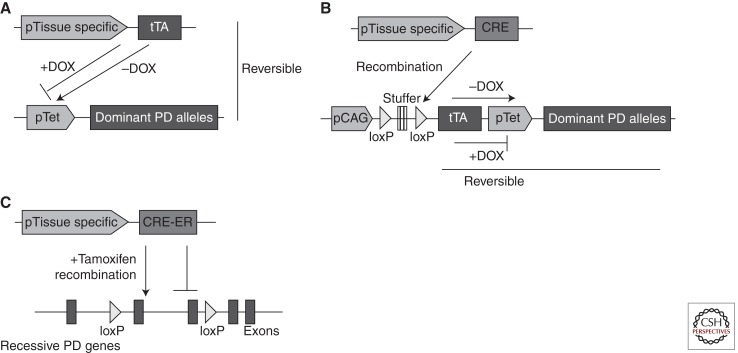

From various transgenic models expressing autosomal-dominant PD genes, it has become clear that robust expression of the transgene is critical in inducing neurodegeneration. In addition, neuron-specific promoters used in previous models tend to be turned on during embryonic neuronal development, thus increasing the chance of adaptation in developing DA neurons against genetic manipulation. Considering these issues together, the best option for improvement of current models is likely a Tet-off conditional transgenic approach that can enable temporal and regional control, together with relatively robust capacity for transgene induction (Sprengel and Hasan 2007). Because several α-syn and LRRK2 tet responder mice are available, efforts should be focused on developing strong driver lines that can drive constitutively high levels of the transgene in cells including DA neurons of the SN in adult mice. Another option would be to use Cre lines to initiate transgene expression (Moeller et al. 2005). In this scenario, we would need to generate transgenic lines that have a stuffer sequence that is flanked by loxP and placed between a constitutively strong promoter (e.g., CAG) and the downstream transgene (e.g., synuclein and LRRK2). Again, transgene expression could be controlled either by using Cre-ER lines (Brocard et al. 1997) in which Cre activity can be controlled by tamoxifen injection or by using additional elements in the transgene itself such as tTA–spacer–tetP just downstream from 3′ loxP sequence (Fig. 1). More available lines of Cre and the property of a reversible switch by the Tet-off system favor the latter strategy.

Figure 1.

Options for conditional PD animal models. Schematics showing tetracycline-regulated conditional transgenic approaches that can offer reversible induction of dominant PD-causing alleles in desired tissues at specific time points. (A) The transgene can be expressed in tissues in which a tissue-specific promoter (pTissue specific) drives tTA. The tetracycline analog doxycycline (DOX) binds to tTA and suppress its ability to activate the Tet-responsive promoter (pTet), thus enabling temporal and reversible regulation over transgene expression. (B) To circumvent the shortage of strong driver lines, the constitutively active chicken β-actin promoter (pCAG) can be used to express tTA, which, in turn, binds and activates pTet downstream. tTA transcription is suppressed by a stuffer sequence downstream from pCAG, but Cre-mediated removal of the stuffer will unleash DOX-regulated reversible transgenic overexpression in specific regions. (C) In the case of autosomal-recessive PD models, a mouse line, which expresses tamoxifen-activated Cre-ER under the control of tissue-specific promoter, can be crossed with conditional lines that have loxP-flanked genes of interest. Temporal regulation over gene deletion will offer the opportunity to avoid potential compensatory pathways that are thought to mask or diminish expected pathological phenotypes in conventional KO mouse models of PD.

As discussed in the previous section, Lenti-Cre delivery to loxP parkin mice successfully reproduces DA neuronal loss in the lifetime of mice. Likewise, Cre-ER-mediated acute deletion of recessive PD genes in adulthood would be promising in generating recessive PD mouse models with DA neurodegeneration. Alternatively transgenic mouse models expressing relevant substrates of parkin or PINK1 could be used to study PD pathogenesis. Because signal exaggeration is more achievable using the previously noted transgenic approaches, substrate transgenic mice are likely to produce desired pathologies at earlier time points. Furthermore, the substrate model will narrow down the pathogenic signaling of recessive PD gene mutations, which, once proven, may provide better therapeutic options for the treatment of PD. Finally, the identification of potential common substrates of parkin and PINK1 would give the opportunity to generate a unifying transgenic model for two major recessive PD genes.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Familial PD can be caused by several monozygotic genetic mutations. In addition, signaling due to these genetic perturbations is thought to contribute to sporadic PD. The modeling of PD in various genetic animal models has provided unprecedented insights on potential mechanisms of neurodegeneration caused by PD gene mutations. The mouse model, among many others, has strong advantages for studying complex genetic disorders including PD: inbred strains of the same genetic background, sophisticated yet accessible methods of genetic manipulation, and a broad spectrum of phenotypical manifestations to cover many of PD’s symptoms and pathologies.

Although none of the current PD animal models fulfills all of the key features of PD, mild deficits in DA transmission and behavioral impairments are reproduced in several models, thus at least providing insight into the physiological changes that may precede actual neurodegeneration. Moreover, many of the α-syn transgenic mice recapitulate the pathologies of synucleinopathy with protein aggregation and neurodegeneration. Because PD represents broad brain pathologies of DA- and non-DA-dependent circuitry with Lewy body protein inclusions, these current α-syn transgenic mice can be successfully tested for therapeutic strategies including chemical or genetic intervention that may reduce aggregation formation and cell death.

There is still a tremendous need for genetic PD mouse models that can recapitulate at least the degeneration of DA neurons in a manageable time window because the ultimate goal in PD research would be the prevention or halting of the degenerative processes of these neurons and others. Advances in mouse technologies provide unparalleled opportunities to refine or reinvent novel PD genetic mouse models: Tet-off conditional transgenic approaches combined with the development of appropriate driver lines and tamoxifen-sensitive Cre-dependent gene deletion with temporal and regional control. Once the PD-related genetic anomalies are modeled in mice without inducing much of the background noise like compensatory changes, thus accomplishing DA neuronal loss in the lifetime of the mice, the global picture of primary initiating signaling events directly relevant to the neuron loss could be parsed out with the aid of diverse exploratory unbiased technologies such as screenings of the proteome, transcriptome, and metabolome. In addition to the potential mining of therapeutic targets, the development of revealing PD genetic models holds tremendous potential to be tested with novel approaches for therapeutic applications such as stem cell implantation, viral-mediated therapies, morpholino siRNA, and, of course, small chemicals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by grants from the NIH, NS38377. T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Y.L. is supported by the Samsung Scholarship Foundation. We acknowledge the joint participation by the Adrienne Helis Malvin Medical Research Foundation through its direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with The Johns Hopkins Hospital, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the Foundation’s Parkinson’s Disease Program No. M-1.

Footnotes

Editor: Serge Przedborski

Additional Perspectives on Parkinson’s Disease available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Andres-Mateos E, Perier C, Zhang L, Blanchard-Fillion B, Greco TM, Thomas B, Ko HS, Sasaki M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, et al. 2007. DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 14807–14812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond CT, Sprengel R, Bissonnette JM, Kaufmann WA, Pribnow D, Neelands T, Storck T, Baetscher M, Jerecic J, Maylie J, et al. 2000. Respiration and parturition affected by conditional overexpression of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel subunit, SK3. Science 289: 1942–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocard J, Warot X, Wendling O, Messaddeq N, Vonesch JL, Chambon P, Metzger D 1997. Spatio-temporally controlled site-specific somatic mutagenesis in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 14559–14563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capecchi MR 1989. The new mouse genetics: Altering the genome by gene targeting. Trends Genet 5: 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Bowling K, Funderburk C, Lawal H, Inamdar A, Wang Z, O’Donnell JM 2007. Interaction of genetic and environmental factors in a Drosophila parkinsonism model. J Neurosci 27: 2457–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Cagniard B, Mathews T, Jones S, Koh HC, Ding Y, Carvey PM, Ling Z, Kang UJ, Zhuang X 2005. Age-dependent motor deficits and dopaminergic dysfunction in DJ-1 null mice. J Biol Chem 280: 21418–21426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchyard A, Lees AJ 1997. The relationship between dementia and direct involvement of the hippocampus and amygdala in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 49: 1570–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang C, Cao JH, Huh JR, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Hay BA, Guo M 2006. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature 441: 1162–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier M, Wellstead P 2010. The control systems structures of energy metabolism. J R Soc Interface 7: 651–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S 2003. Parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms and models. Neuron 39: 889–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Kholodilov N, Vila M, Trillat AC, Goodchild R, Larsen KE, Staal R, Tieu K, Schmitz Y, Yuan CA, et al. 2002. Resistance of α-synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 14524–14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Ko HS, Dawson VL 2010. Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 66: 646–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev KK, Hofele K, Barbieri S, Buchman VL, van der Putten H 2003. Part II: α-Synuclein and its molecular pathophysiological role in neurodegenerative disease. Neuropharmacology 45: 14–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernagut PO, Chesselet MF 2004. α-Synuclein and transgenic mouse models. Neurobiol Dis 17: 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forno LS 1987. The Lewy body in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol 45: 35–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Zhang J 2003. Why are some human disease-associated mutations fixed in mice? Trends Genet 19: 678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier CA, Kitada T, Shen J 2008. Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Duda JE, Quinn SM, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM 2002. Neuronal α-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human α-synuclein. Neuron 34: 521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gispert S, Del Turco D, Garrett L, Chen A, Bernard DJ, Hamm-Clement J, Korf HW, Deller T, Braak H, Auburger G, et al. 2003. Transgenic mice expressing mutant A53T human α-synuclein show neuronal dysfunction in the absence of aggregate formation. Mol Cell Neurosci 24: 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gispert S, Ricciardi F, Kurz A, Azizov M, Hoepken HH, Becker D, Voos W, Leuner K, Muller WE, Kudin AP, et al. 2009. Parkinson phenotype in aged PINK1-deficient mice is accompanied by progressive mitochondrial dysfunction in absence of neurodegeneration. PloS ONE 4: e5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Fleming SM, Palacino JJ, Cepeda C, Lam HA, Bhatnagar A, Meloni EG, Wu N, Ackerson LC, Klapstein GJ, et al. 2003. Parkin-deficient mice exhibit nigrostriatal deficits but not loss of dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem 278: 43628–43635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MS, Pisani A, Haburcak M, Vortherms TA, Kitada T, Costa C, Tong Y, Martella G, Tscherter A, Martins A, et al. 2005. Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism-linked gene DJ-1. Neuron 45: 489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldwurm S, Di Fonzo A, Simons EJ, Rohe CF, Zini M, Canesi M, Tesei S, Zecchinelli A, Antonini A, Mariani C, et al. 2005. The G6055A (G2019S) mutation in LRRK2 is frequent in both early and late onset Parkinson’s disease and originates from a common ancestor. J Med Genet 42: e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Bujard H 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 5547–5551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, Kondapalli J, Ilijic E, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ 2010. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature 468: 696–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itier JM, Ibanez P, Mena MA, Abbas N, Cohen-Salmon C, Bohme GA, Laville M, Pratt J, Corti O, Pradier L, et al. 2003. Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet 12: 2277–2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RH, Smith PD, Aleyasin H, Hayley S, Mount MP, Pownall S, Wakeham A, You-Ten AJ, Kalia SK, Horne P, et al. 2005. Hypersensitivity of DJ-1-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrindine (MPTP) and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 5215–5220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Annett LE, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Bjorklund A 2003. Nigrostriatal α-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human α-synuclein: A new primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 2884–2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner A, Gossen M, Zimmermann F, Jerecic J, Ullmer C, Lubbert H, Bujard H 1996. Doxycycline-mediated quantitative and tissue-specific control of gene expression in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 10933–10938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Pisani A, Porter DR, Yamaguchi H, Tscherter A, Martella G, Bonsi P, Zhang C, Pothos EN, Shen J 2007. Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of PINK1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 11441–11446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Tong Y, Gautier CA, Shen J 2009. Absence of nigral degeneration in aged parkin/DJ-1/PINK1 triple knockout mice. J Neurochem 111: 696–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HS, von Coelln R, Sriram SR, Kim SW, Chung KK, Pletnikova O, Troncoso J, Johnson B, Saffary R, Goh EL, et al. 2005. Accumulation of the authentic parkin substrate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cofactor, pp38/JTV-1, leads to catecholaminergic cell death. J Neurosci 25: 7968–7978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko HS, Kim SW, Sriram SR, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2006. Identification of far upstream element-binding protein-1 as an authentic Parkin substrate. J Biol Chem 281: 16193–16196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh DW, Dawson TM, Dawson VL 2005. Mediation of cell death by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Pharmacol Res 52: 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landel CP, Chen SZ, Evans GA 1990. Reverse genetics using transgenic mice. Annu Rev Physiol 52: 841–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Stirling W, Xu Y, Xu X, Qui D, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL 2002. Human α-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson’s disease-linked Ala-53 → Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with α-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 8968–8973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BD, Shin JH, VanKampen J, Petrucelli L, West AB, Ko HS, Lee YI, Maguire-Zeiss KA, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, et al. 2010. Inhibitors of leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 protect against models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med 16: 998–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu W, Oo TF, Wang L, Tang Y, Jackson-Lewis V, Zhou C, Geghman K, Bogdanov M, Przedborski S, et al. 2009. Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci 12: 826–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Parisiadou L, Gu XL, Wang L, Shim H, Sun L, Xie C, Long CX, Yang WJ, Ding J, et al. 2009. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson’s-disease-related mutant α-synuclein. Neuron 64: 807–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Bianco C, Ridet JL, Schneider BL, Deglon N, Aebischer P 2002. α-Synucleinopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 10813–10818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandir AS, Przedborski S, Jackson-Lewis V, Wang ZQ, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Smulson ME, Hoffman BE, Guastella DB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 1999. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation mediates 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 5774–5779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Pan Y, Price AC, Sterling W, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Lee MK 2006. Parkinson’s disease α-synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J Neurosci 26: 41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2011. Recent advances in the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 12: 301–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L 2000. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in α-synuclein mice: Implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science 287: 1265–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller MJ, Soofi A, Sanden S, Floege J, Kriz W, Holzman LB 2005. An efficient system for tissue-specific overexpression of transgenes in podocytes in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F481–F488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2003. Genetics of Parkinson’s disease: What do mutations in DJ-1 tell us? Ann Neurol 54: 281–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2005. Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 57–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Kahle PJ, Giasson BI, Ozmen L, Borroni E, Spooren W, Muller V, Odoy S, Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, et al. 2002. Misfolded proteinase K-resistant hyperphosphorylated α-synuclein in aged transgenic mice with locomotor deterioration and in human α-synucleinopathies. J Clin Invest 110: 1429–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto M, Gil-Bea FJ, Dalfo E, Cuadrado M, Cabodevilla F, Sanchez B, Catena S, Sesma T, Ribe E, Ferrer I, et al. 2006. Increased sensitivity to MPTP in human α-synuclein A30P transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 27: 848–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuber S, Petrasch-Parwez E, Winner B, Winkler J, von Horsten S, Schmidt T, Boy J, Kuhn M, Nguyen HP, Teismann P, et al. 2008. Neurodegeneration and motor dysfunction in a conditional model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci 28: 2471–2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzscha H, Schermann SM, Woerner AC, Pinkert S, Hecht MH, Tartaglia GG, Vendruscolo M, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Vabulas RM 2011. Amyloid-like aggregates sequester numerous metastable proteins with essential cellular functions. Cell 144: 67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterna JC, Leng A, Weber E, Feldon J, Bueler H 2007. DJ-1 and Parkin modulate dopamine-dependent behavior and inhibit MPTP-induced nigral dopamine neuron loss in mice. Mol Ther 15: 698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez FA, Curtis WR, Palmiter RD 2005. Parkin-deficient mice are not more sensitive to 6-hydroxydopamine or methamphetamine neurotoxicity. BMC Neurosci 6: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, et al. 1997. Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science 276: 2045–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonet D, Daher JP, Lin BM, Stafa K, Kim J, Banerjee R, Westerlund M, Pletnikova O, Glauser L, Yang L, et al. 2011. Dopaminergic neuronal loss, reduced neurite complexity and autophagic abnormalities in transgenic mice expressing G2019S mutant LRRK2. PloS ONE 6: e18568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richfield EK, Thiruchelvam MJ, Cory-Slechta DA, Wuertzer C, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG, Di Monte DA, Federoff HJ 2002. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of wild-type and mutated human α-synuclein in transgenic mice. Exp Neurol 175: 35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockenstein E, Crews L, Masliah E 2007. Transgenic animal models of neurodegenerative diseases and their application to treatment development. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 59: 1093–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal N, Brown S 2007. The mouse ascending: Perspectives for human-disease models. Nat Cell Biol 9: 993–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulicke T, Montagutelli X, Pintado B, Thon R, Hedrich HJ 2007. FELASA guidelines for the production and nomenclature of transgenic rodents. Lab Anim 41: 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitt JM, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2006. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: Molecules to medicine. J Clin Invest 116: 1744–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee YI, Pletinkova O, Troconso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2011. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1α contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell 144: 689–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic F, Yi M, Wang Y, Macey L, Brown LT, Krichevsky AM, Andersen SL, Stephens RM, Benes FM, Sonntag KC 2009. Gene expression profiling of substantia nigra dopamine neurons: Further insights into Parkinson’s disease pathology. Brain 132: 1795–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, et al. 2003. α-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 302: 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song DD, Shults CW, Sisk A, Rockenstein E, Masliah E 2004. Enhanced substantia nigra mitochondrial pathology in human α-synuclein transgenic mice after treatment with MPTP. Exp Neurol 186: 158–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M 1997. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388: 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengel R, Hasan MT 2007. Tetracycline-controlled genetic switches. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2007: 49–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, von Coelln R, Mandir AS, Trinkaus DB, Farah MH, Leong Lim K, Calingasan NY, Flint Beal M, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2007. MPTP and DSP-4 susceptibility of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus catecholaminergic neurons in mice is independent of parkin activity. Neurobiol Dis 26: 312–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Mandir AS, West N, Liu Y, Andrabi SA, Stirling W, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Lee MK 2011. Resistance to MPTP-neurotoxicity in α-synuclein knockout mice is complemented by human α-synuclein and associated with increased β-synuclein and Akt activation. PloS ONE 6: e16706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Shen J 2009. α-Synuclein and LRRK2: Partners in crime. Neuron 64: 771–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Coelln R, Thomas B, Savitt JM, Lim KL, Sasaki M, Hess EJ, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2004. Loss of locus coeruleus neurons and reduced startle in parkin null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 10744–10749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xie C, Greggio E, Parisiadou L, Shim H, Sun L, Chandran J, Lin X, Lai C, Yang WJ, et al. 2008. The chaperone activity of heat shock protein 90 is critical for maintaining the stability of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2. J Neurosci 28: 3384–3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, Agarwala R, Ainscough R, Alexandersson M, An P, et al. 2002. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420: 520–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM 2005. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 16842–16847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, Andrabi SA, Li X, Dikeman D, Biskup S, Zhang Z, Lim KL, Dawson VL, et al. 2007. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 16: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild P, Dikic I 2010. Mitochondria get a Parkin’ ticket. Nat Cell Biol 12: 104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Falkenburger BH, Schulz JB, Tieu K, Xu Z, Xia XG 2007. Silencing of the Pink1 gene expression by conditional RNAi does not induce dopaminergic neuron death in mice. Int J Biol Sci 3: 242–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]