Abstract

Objectives:

To assess health-related quality of life (HRQL) over 2 years in children 4−12 years old with new-onset epilepsy and risk factors.

Methods:

Data are from a multicenter prospective cohort study, the Health-Related Quality of Life Study in Children with Epilepsy Study (HERQULES). Parents reported on children's HRQL and family factors and neurologists on clinical characteristics 4 times. Mean subscale and summary scores were computed for HRQL. Individual growth curve models identified trajectories of change in HRQL scores. Multiple regression identified baseline risk factors for HRQL 2 years later.

Results:

A total of 374 (82) questionnaires were returned postdiagnosis and 283 (62%) of eligible parents completed all 4. Growth rates for HRQL summary scores were most rapid during the first 6 months and then stabilized. About one-half experienced clinically meaningful improvements in HRQL, one-third maintained their same level, and one-fifth declined. Compared with the general population, at 2 years our sample scored significantly lower on one-third of CHQ subscales and the psychosocial summary. After controlling for baseline HRQL, cognitive problems, poor family functioning, and high family demands were risk factors for poor HRQL 2 years later.

Conclusions:

On average, HRQL was relatively good but with highly variable individual trajectories. At least one-half did not experience clinically meaningful improvements or declined over 2 years. Cognitive problems were the strongest risk factor for compromised HRQL 2 years after diagnosis and may be largely responsible for declines in the HRQL of children newly diagnosed with epilepsy.

The primary goal in managing epilepsy is to optimize patients' health-related quality of life (HRQL) by affording them a lifestyle as free as possible from the medical and psychosocial sequelae of seizures.1,2 Empirical evidence of the natural course of HRQL and associated risk factors is an essential step toward providing prognostic information to patients and families and determining key factors along the causal pathway that may be amenable to interventions to mute the potential negative effects of epilepsy on HRQL. Most empirical assessments of HRQL in children with epilepsy (CWE) have focused on a specific aspect of HRQL (e.g., psychological well-being, social competence, or behavior). Of the comprehensive, multidimensional assessments of HRQL in children, most had small samples and focused on selected subgroups such as adolescents,3,4 children with intractable/refractory epilepsy,5,6 or children who had undergone epilepsy surgery.7,8 Evidence suggests that CWE experience diminished HRQL compared with healthy control subjects.9

This article describes the course of HRQL over the first 2 years postdiagnosis in children 4−12 years old and child and family risk factors at diagnosis for HRQL 2 years later. We hypothesized that HRQL would improve over time with worst HRQL reported postdiagnosis and best 2 years later and that child and family characteristics at the time of diagnosis would each predict HRQL 2 years postdiagnosis.

METHODS

Sample and procedures.

Data were collected in the Health-Related Quality of Life Study in Children with Epilepsy Study (HERQULES), a multicenter prospective cohort study of children with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Pediatric neurologists across Canada approached parents about the study. Inclusion criteria were a new case of epilepsy (≥2 unprovoked seizures) in a child 4−12 years old, in whom diagnosis had not been confirmed previously, seen for the first time by a pediatric neurologist and a parent with sufficient English language skills, primarily responsible for the child's care for at least 6 months. The Tailored Design Method for surveys was followed.10

Standard protocol approvals, regulations and patient consents.

Parents received a letter describing the study and outlining what participation entailed. Parents completed 4 mailed questionnaires (postdiagnosis and 6, 12, and 24 months later) and consented for their child's neurologist to provide clinical information at the same time points. The study protocol received approval from all relevant research ethics boards.

Measures.

Additional details are available (see appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org). Missing data were handled according to instructions of individual scale developers.

HRQL was assessed using an epilepsy-specific measure, Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy Questionnaire (QOLCE)11 (76-item version), and a generic measure, Child Health Questionnaire−Parent Form (CHQ),12 50-item version.

Epilepsy characteristics.

Neurologists reported on types of seizures and of epilepsy syndrome, frequency of seizures, and medication and adverse effects and classified severity of epilepsy, using the Global Assessment of Severity of Epilepsy (GASE)13 to rate overall severity on a scale from 1 (extremely severe) to 7 (not at all severe). GASE has adequate content, convergent, and construct validity and high intra- and interrater reliability.13 They also rated comorbidities using single items adapted from previous studies,14 specifically, any behavior (0 = none to 3 = severe) or cognitive problems (0 = none to 4 = severe). The classifications of the International League Against Epilepsy15,16 guided the categorization of neurologists' reports of epilepsy/epilepsy syndrome types.

Family environment.

The Family Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve (Family APGAR) assessed satisfaction with family relationships.17 The Family Inventory of Resources for Management (FIRM) measured resources available to aid families' adaptation to stressful events.18 Two subscales (family mastery and health and extended family social support), associated with adaptation to childhood epilepsy, were used.19 Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes (FILE) indexed family stress in the previous year.20 Parents' depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).21 Sociodemographic information collected included date of birth and sex (parent and child), number of children in household, parents' marital status, employment status, and education level, and annual household income.

Statistical analysis.

Summary statistics and frequency distributions were used to describe the sample at baseline and 2 years. Pearson correlations assessed associations between continuous baseline variables and HRQL at 2 years.

Means were computed for each subscale and summary scale of the QOLCE and CHQ. For QOLCE-Overall, CHQ-Physical, and CHQ-Psychosocial summary scores, growth curve modeling was applied to determine profiles over 2 years. Months since diagnosis was used to estimate the magnitude and direction of a single trajectory averaging all individual trajectories for the sample. Individual differences were captured by estimating a random coefficient representing variability around the averaged intercept and slope. Results for model selection are described in appendix e-2.

Given no well-established minimal clinically important differences for the HRQL measures, we used a standard error of measurement (SEM)−based criterion to identify how many children experienced clinically meaningful changes over 2 years. Scores of at least 1 SEM are interpreted as clinically important when used with psychometrically robust HRQL measures to reveal intraindividual changes.22

Finally, we compared CHQ subscale and summary scores from our sample of CWE postdiagnosis and 2 years later with published norms for similarly aged children from the US general population12 using two-sample t tests.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tested for differences in mean QOLCE scores across levels of categorical baseline variables. Multiple regression using a backward, stepwise algorithm identified predictive baseline factors for HRQL at 2 years. The significance level for variables to enter and remain in the model was α = 0.10. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.2. All tests were two-sided using p < 0.05 as statistically significant. The level of statistical significance in two-sample t tests was adjusted with the Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics.

Of a total of 72 pediatric neurologists treating children with new-onset epilepsy in Canada, 53 (74%) recruited families with a median 9 per physician. From 456 eligible children, parents of 374 returned completed postdiagnosis questionnaires (response rate 82%); 283 (62%) completed all 4 questionnaires. Those with complete data did not differ from those who dropped out on children's baseline type of seizures, severity of epilepsy, behavior problems, or levels of HRQL. Parents who completed all 4 questionnaires were older (p = 0.0033), were more likely to be married (p = 0.0002), and had more education (p = 0.0014) and higher income (p = 0.0055), and their children were less likely to have cognitive problems (p = 0.0126).

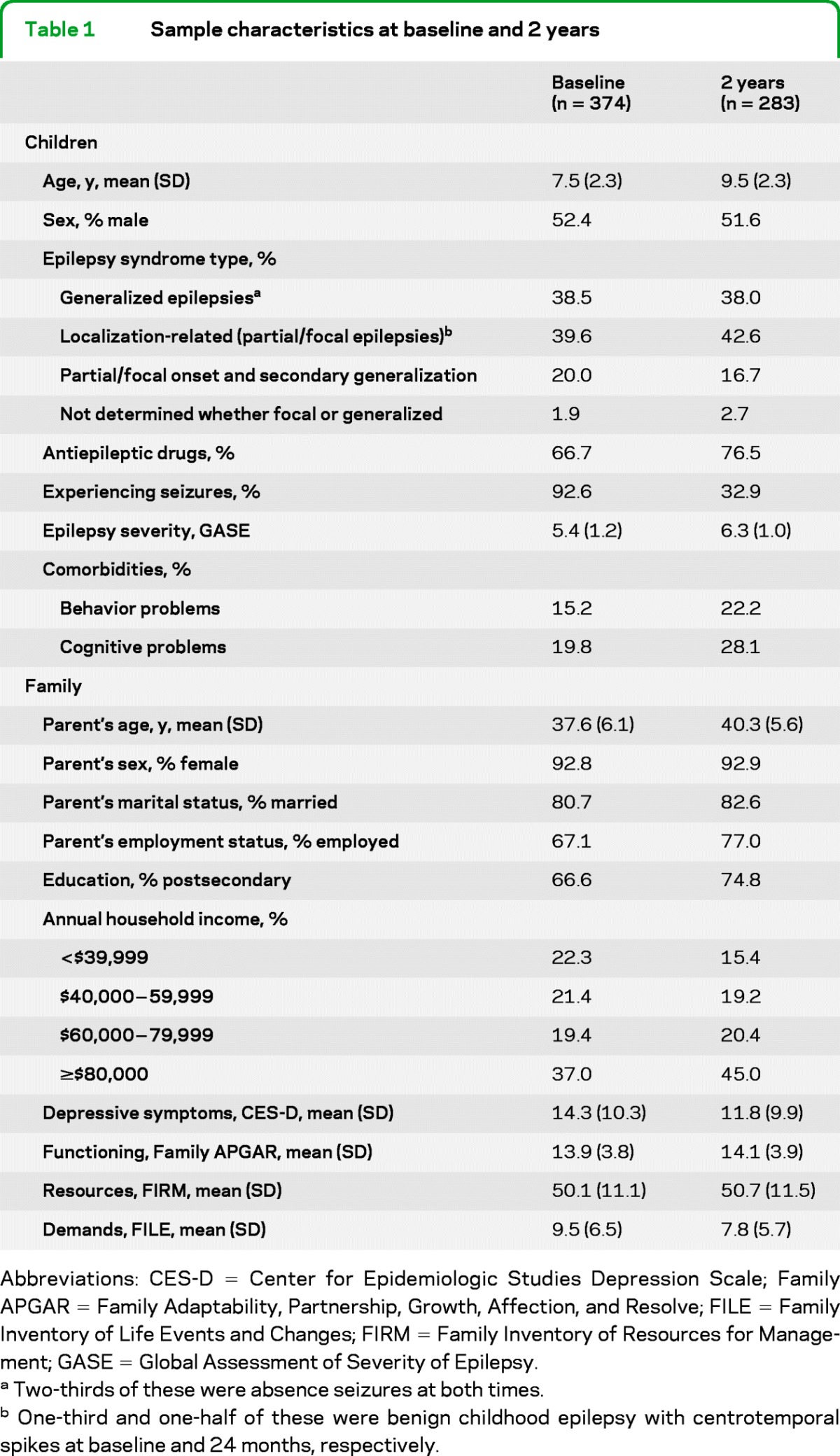

Table 1shows sample characteristics at baseline and 2 years postdiagnosis. Overall, children had less severe types of epilepsy, and families were functioning well and had adequate resources and relatively few demands on them.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline and 2 years

Abbreviations: CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; Family APGAR = Family Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve; FILE = Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes; FIRM = Family Inventory of Resources for Management; GASE = Global Assessment of Severity of Epilepsy.

Two-thirds of these were absence seizures at both times.

One-third and one-half of these were benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes at baseline and 24 months, respectively.

Course of HRQL over 2 years.

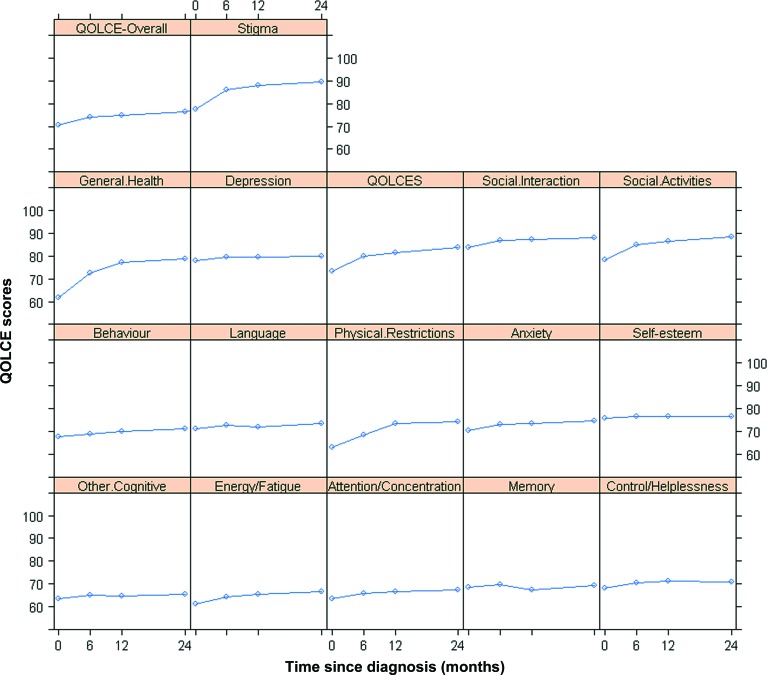

For both measures of HRQL, the course was very similar with mean scores being lowest at baseline for all subscales and highest 2 years after diagnosis for most. The figure depicts parents' reports of children's HRQL over 2 years using the QOLCE.

Figure. Mean Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy Questionnaire (QOLCE) scores (subscales and overall).

Baseline and 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years later.

Modeling the course of HRQL.

Modeling the course of HRQL showed that, postdiagnosis, patients had a mean QOLCE-Overall of 70.7, CHQ-Psychosocial of 48.8, and CHQ-Physical of 44.8. The model-building process suggested that models with quadratic time terms were adequate to describe the curvature pattern of these 3 measures (p < 0.001) (see supplemental information in appendix e-2). Respective growth rates were most rapid during the first 6 months after diagnosis and then slowed gradually with a 2-year mean QOLCE-Overall of 75.7, CHQ-Psychosocial of 51.4, and CHQ-Physical of 47.7.

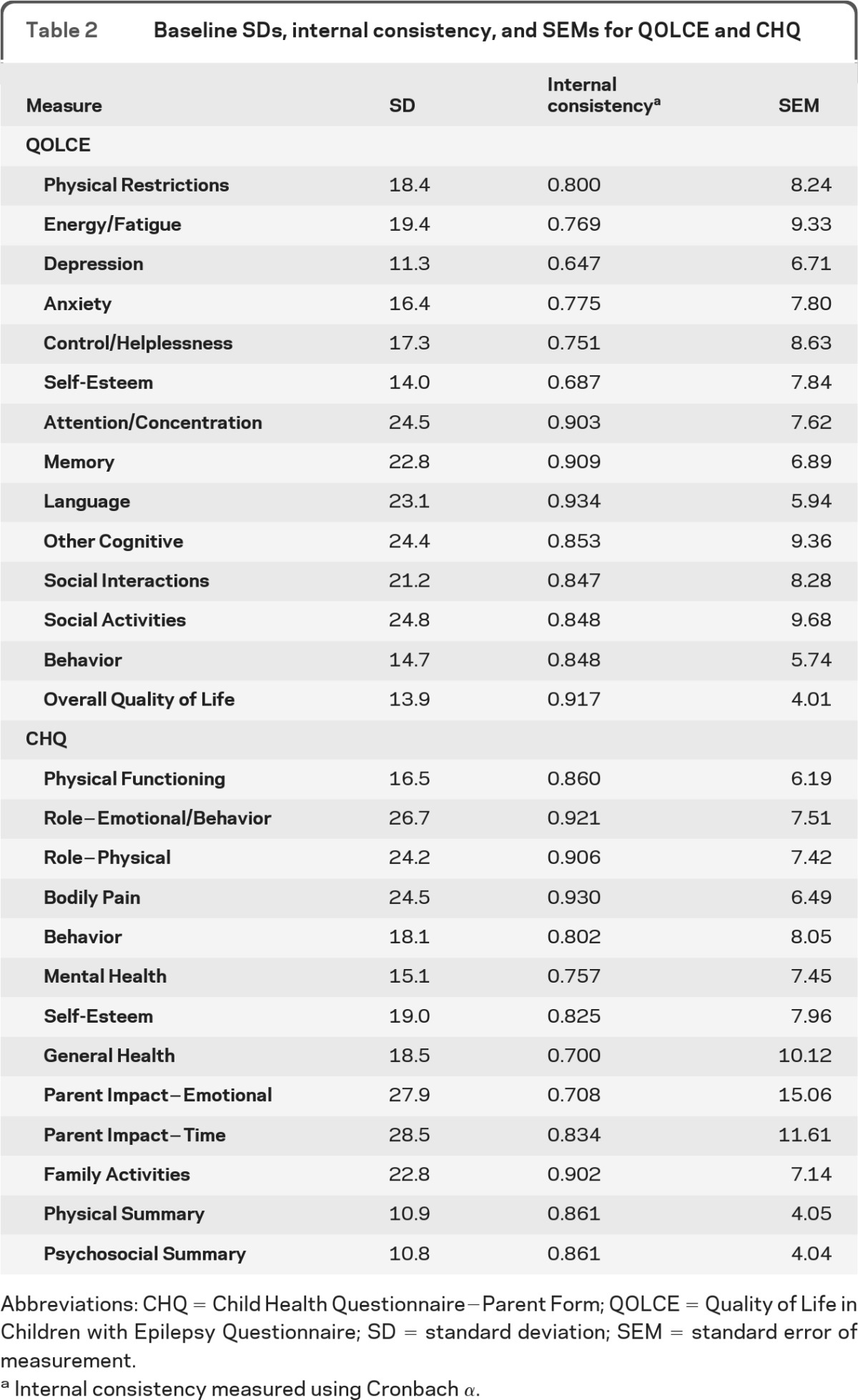

Clinically important changes in HRQL over 2 years.

SEM calculated for each baseline QOLCE and CHQ subscale and the summary mean score (table 2) estimated the proportion of children who experienced clinically important changes in HRQL over 2 years. Using the QOLCE-Overall, 50% experienced either no clinically important improvement (32%) or a clinically important decline (18%). Using the CHQ-Psychosocial, 56% experienced either no clinically important improvement (37%) or a clinically important decline (19%). On the CHQ-Physical, 61% experienced either no clinically important improvement (43%) or a clinically important decline (18%).

Table 2.

Baseline SDs, internal consistency, and SEMs for QOLCE and CHQ

Abbreviations: CHQ = Child Health Questionnaire−Parent Form; QOLCE = Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy Questionnaire; SD = standard deviation; SEM = standard error of measurement.

Internal consistency measured using Cronbach α.

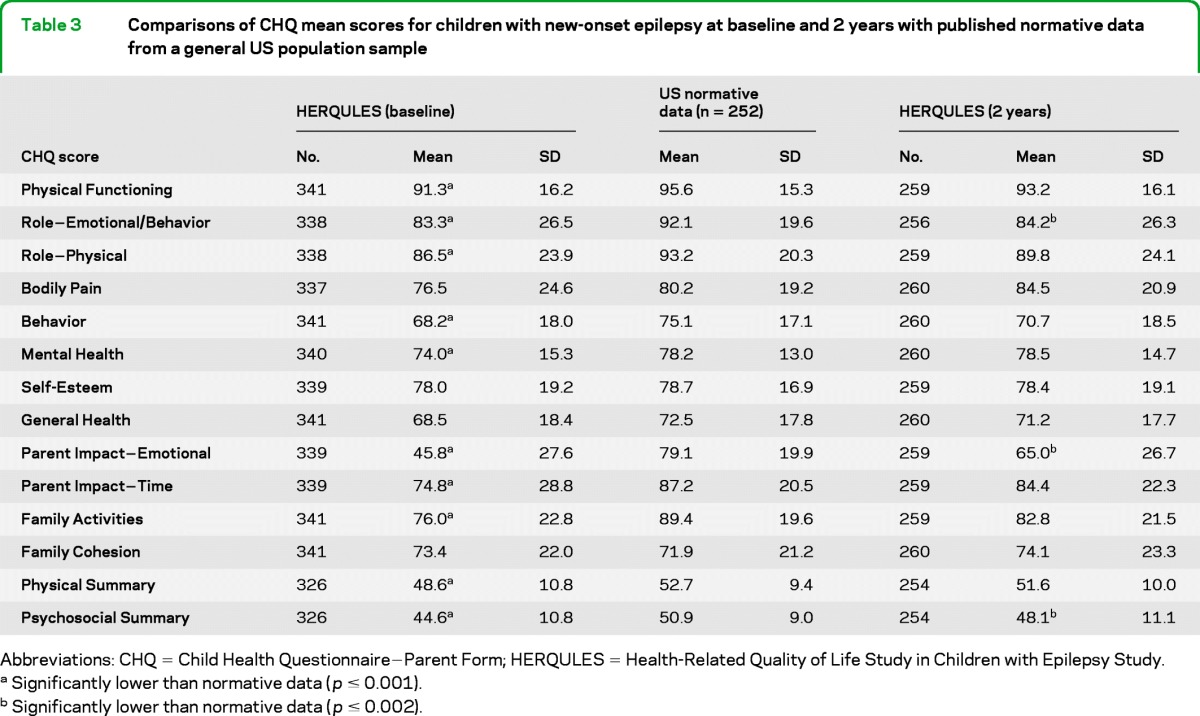

Comparison of HRQL with that of normative controls.

We compared CHQ scores at baseline and 2 years later with published normative data from a general US population sample of 252 children aged 5−18 years (table 3). At baseline, CWE had lower means on all subscales, except Bodily Pain, General Health, Self-Esteem, and Family Cohesion. The epilepsy sample also scored lower on physical and psychosocial summary scores. The largest difference was on emotional impact on parents. At 2 years, the CWE remained lower on 3 subscales (one focusing on the child [Role−Emotional/Behavior] and 2 focusing on family impact [Parent Impact−Emotional and Family Activities]). The epilepsy sample also scored lower on the CHQ-Psychosocial. Again, the largest difference was for Parent Impact−Emotional for which the mean for parents of CWE was still 14 points lower than that for the general population.

Table 3.

Comparisons of CHQ mean scores for children with new-onset epilepsy at baseline and 2 years with published normative data from a general US population sample

Abbreviations: CHQ = Child Health Questionnaire−Parent Form; HERQULES = Health-Related Quality of Life Study in Children with Epilepsy Study.

Significantly lower than normative data (p ≤ 0.001).

Significantly lower than normative data (p ≤ 0.002).

Predictors of HRQL.

Unadjusted associations between baseline risk factors and QOLCE scores 2 years later were conducted using Pearson correlations and ANOVA (table e-1). Children who, at baseline, had higher QOLCE (r = 0.60), Family APGAR (r = 0.31), and FIRM scores (r = 0.36; p < 0.0001 for each), with no behavior (F = 24.63) or cognitive problems (F = 42.35; p < 0.0001 for each, and families with higher income (F = 5.31; p = 0.0004) had higher QOLCE scores 2 years later. In addition, children prescribed more antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) (r = −0.13; p = 0.0368), with higher parental CES-D scores (r = −0.36; p < 0.0001) and family FILE scores (r = −0.30; p < 0.0001) had lower QOLCE scores at 2 years.

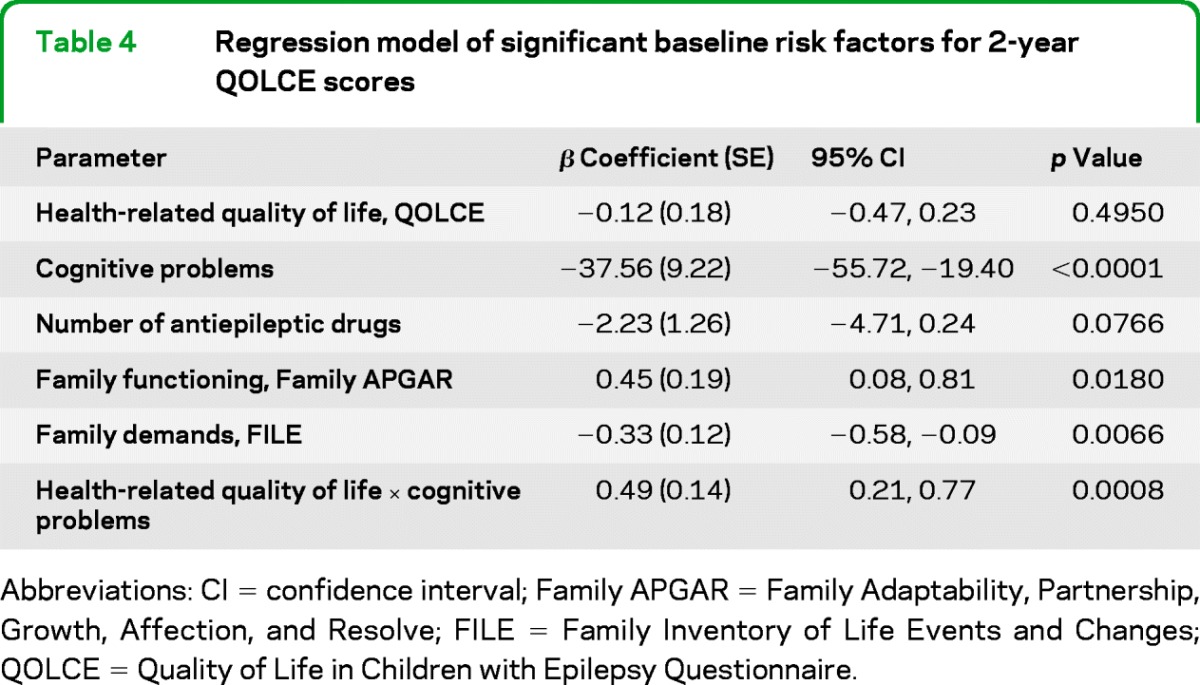

Variables significant in the unadjusted analysis were used to identify predictors of QOLCE scores at 2 years. Controlling for baseline HRQL, the risk factors for better HRQL 2 years later were absence of cognitive problems, fewer AEDs, higher family functioning, and fewer family demands (table 4). There was a qualitative interaction between baseline HRQL and cognitive problems, whereby predicted HRQL was highest for children with high HRQL at baseline and no cognitive problems, followed by children with low HRQL at baseline and no cognitive problems and lowest for children with high HRQL and cognitive problems at baseline. This result suggests that cognitive problems may be the driving force behind declining HRQL over 2 years. The data fit the model well (F6,247 = 32.34; p < 0.0001) and accounted for nearly half the variation observed in QOLCE scores at 2 years (r2 = 0.45; p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Regression model of significant baseline risk factors for 2-year QOLCE scores

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; Family APGAR = Family Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve; FILE = Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes; Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy Questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

Children aged 4−12 diagnosed with epilepsy generally have good HRQL during the first 2 years postdiagnosis on average. This finding is probably related to the fact that children diagnosed at these ages tend to have less severe epilepsy.23 HRQL was initially compromised and then improved over 2 years, on average, with the largest change during the first 6 months and a slower rate of change between 6 and 24 months. This pattern probably reflects the fact that a period of acute adjustment to the diagnosis is typical over the short-term after which time less dramatic adjustments occur. Individual trajectories of HRQL varied, however, with some children improving and some declining.

There is only one other published prospective study of HRQL in children with new-onset epilepsy, which followed 118 children aged 2−12 years for 7 months to assess the effect of treatment on HRQL.24 In that study, HRQL remained constant, except for a positive trend in emotional functioning and side effects of AEDs. Frequency of seizures negatively affected HRQL. We think 3 of the authors' explanations for HRQL not improving over time as anticipated may explain the differences between their findings and ours: 1) their sample received extensive education to ease adaptation to epilepsy; 2) they found, as we did, that individual trajectories varied with improvements in some children and declines in others; and 3) those who achieved seizure control in the other study did improve over time (33% of our sample experienced seizures at 2 years compared with 93% at baseline).

Compared with published normative data of similarly aged children from the general population, children with new-onset epilepsy had poorer HRQL at the first assessment on most domains. Two years later, ratings were more similar but still lower on psychosocial health. Notably, parents of CWE still reported much more emotional worry for their children's health at 2 years.

The baseline child and family risk factors that predict HRQL 2 years after diagnosis, controlling for baseline HRQL, were absence of cognitive problems, fewer AEDs prescribed, and better family environment. These predicted higher HRQL 2 years later. Neither severity nor type of epilepsy predicted HRQL. The effect of cognitive problems on HRQL at 2 years depends on baseline HROL.

That presence of cognitive problems predicts later HRQL is understandable given that cognition is an important domain in the overall HRQL construct.25 In fact, previous research has shown that cognitive impairment in CWE is associated with diminished HRQL.26 The mechanism underlying the relationship between number of AEDs and HRQL is not clear. Number of AEDs may be a proxy for difficulty controlling seizures. Further research examining the relationship between number of AEDs and neurologists' perceptions of difficulty managing seizures is needed to better elucidate the impact on children's HRQL.

The finding that family functioning and demands were risk factors for HRQL 2 years after diagnosis is novel. Whereas previous research has shown family environment to be associated with child psychopathology,26 cognitive and behavioral functioning, and academic achievement,27 the impact on HRQL has not been examined. Recently, family functioning was shown to protect against declines in self-esteem, a component of HRQL, among children with a first seizure.28

It is interesting that no parental characteristic, specifically depressive symptoms, was retained in the final predictive model because depressive symptoms in parents have been associated with child HRQL in epilepsy.29 The modeling strategy showed that parental depressive symptoms was eliminated in the final step of model building (data not shown). This finding is congruent with a mediation pathway and corroborates our previous work demonstrating that family functioning and demands mediate the impact of maternal depression on child HRQL in new-onset epilepsy.30

Of particular interest is the qualitative interaction between baseline HRQL and cognitive problems in predicting HRQL at 2 years. Controlling for number of AEDs and family environment, predicted HRQL was best for children with good HRQL at baseline and no cognitive problems, followed by children with poor HRQL at baseline and no cognitive problems. This result suggests that, regardless of HRQL at baseline, children without cognitive problems have better outcomes during the first 2 years postdiagnosis. Children with the worst predicted HRQL at 2 years were those with good HRQL and cognitive problems at baseline, suggesting that cognitive problems may be the driving force behind declining HRQL during the first 2 years. Children with poor HRQL and cognitive problems at baseline have slightly better HRQL at 2 years than children with good HRQL and cognitive problems at baseline. This finding may be attributed to the phenomenon of response shift: a change in the meaning of parents' evaluation of children's HRQL resulting from a change in parents' internal standards, values, or concept of HRQL.31 Thus, whereas the initial stress associated with the diagnosis may lead parents to report poor HRQL in their children, their experience with epilepsy and developing coping mechanisms may lead to a more positive recalibration of HRQL at 2 years postdiagnosis.31 Further exploration of potential response shift is needed to substantiate this hypothesis.

This study has several strengths: it was a large, multicenter, prospective cohort study with strong response and retention rates; incident cases with diverse types of epilepsy were included so that results would be useful during the initial medical consultation to promote the best possible HRQL in CWE; valid and reliable measures assessed child and family characteristics including both a generic and epilepsy-specific measure of HRQL; a methodologically rigorous modeling strategy produced a robust set of predictors; and the stability of predictors is supported by the fact that the same child and family characteristics also predicted HRQL at 12 months (data not shown).

The study also has some limitations. First, there were parent and neurologist reports but no patient report. A mail survey was the most viable data collection strategy, given the national scope of the study, and it would have been impossible to ascertain whether children completed questionnaires independently. Because only children 8 years of age or older can reliably self-report,32 not all participants were eligible. In support of mothers as reporters, we previously reported encouraging results from this same sample that mothers' reports of children's HRQL were not affected by mothers' depressive symptoms.33 Parent report has been found to be an adequate substitute for child report at the group level, as used here,34 but a recent study of CWE35 found that parents reported poorer HRQL than children themselves. Recognizing the importance of patient report, it is included in the subsequent follow-up of this cohort currently under way.

Second, we recruited from pediatric neurology practices, possibly not representative of all families of a child with epilepsy. Although some children are diagnosed by primary care pediatricians or family practitioners, it is not feasible to recruit a random sample of such physicians in a large national study. We demonstrated previously that it may be feasible to recruit a representative population-based sample of CWE by sampling pediatric neurologists. Family physicians referred between 80 and 99% of CWE (depending on type) to a pediatric neurologist.36

Third, as is typical of longitudinal studies, there was some attrition, which might produce a biased subsample at the 2-year follow-up. Children for whom we have complete follow-up did not differ from those lost to follow-up on baseline type of seizures, severity of epilepsy, behavior problems, or level of HRQL, but they were more likely to have cognitive problems. Parents completing all questionnaires tended to be older, were more likely to be married, and had higher education and income. Thus, our sample may be biased toward families with more resources to deal with epilepsy. Given that family environment predicted children's HRQL, the impact of epilepsy on children's HRQL may be underestimated.

Finally, in the absence of Canadian general population norms for HRQL, we compared our results with US norms for the CHQ. Although not ideal, it is a common practice based on an assumption that parents in the 2 countries probably report their children's HRQL similarly.

Our results suggest that it may be possible to identify children at risk for compromised HRQL soon after diagnosis of epilepsy, presenting an opportunity to target families for resources. There may be value in evaluating whether a family-centered approach beginning at diagnosis that includes supportive resources targeting families with children at high risk for poor HRQL would have a positive impact on the level of HRQL children achieve.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the parents and physicians and their staff, without whose participation this study would not have been possible and thank the HERQULES staff, especially Jane Terhaerdt. The Canadian Pediatric Epilepsy Network effectively facilitated the participation of physician contributors across the country: in British Columbia: Coleen Adams, Bruce Bjornson, Margaret Clark, Mary Connolly, Kevin Farrell, Juliette Hukin, Steven Miller, Elke Roland, Kathryn Selby, and Katherine Wambera; in Alberta: Karen Barlow, Lorie Hamiwka, Jean Mah, Bev Prieur, Lawrence Richer, Barry Sinclair, Elaine Wirrell, and Jerome Yager; in Saskatchewan: Richard Huntsman, Noel Lowry, and Shashi Seshia; in Manitoba: Fran Booth, Charuta Joshi, Mubeen Rafay, and Michael Salman; in Ontario: Craig Campbell, Pam Cooper, Asif Doja, Pierre Jacob, Daniel Keene, Betty Koo, Wayne Langburt, Simon Levin, Robert Munn, Minh Nguyen, Narayan Prasad, Sharon Whiting, and Conrad Yim; in Quebec: Lionel Carmant, Paola Diadori, Marie-Emmanuelle Dilenge, Albert Larbrisseau, Alison Moore, Chantel Poulin, Bernie Rosenblatt, Michael Shevell, and Michel Vanasse; in New Brunswick: David Meek; in Nova Scotia: Carol Camfield, Peter Camfield, Joe Dooley, Kevin Gordon, and Ellen Wood; in Newfoundland: Muhammad Alam and David Buckley.

Glossary

GLOSSARY

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- CHQ

Child Health Questionnaire−Parent Form

- CWE

children with epilepsy

- Family APGAR

Family Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve

- FILE

Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes

- FIRM

Family Inventory of Resources for Management

- GASE

Global Assessment of Severity of Epilepsy

- HERQULES

Health-Related Quality of Life Study in Children with Epilepsy Study

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- QOLCE

Quality of Life in Children with Epilepsy Questionnaire

- SEM

standard error of measurement

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.N. Speechley: study concept and design, obtaining funding, study supervision, interpretation of data, drafting and revising manuscript for content. M.A. Ferro: analysis and interpretation and drafting of section on risk factors, revising manuscript for content. C.S. Camfield: study design, obtaining funding, revising manuscript for content. W. Huang: analysis of data for course of HRQL. S.D. Levin: study concept and design, obtaining funding, acquisition of data. M.L. Smith: study design, obtaining funding, revising manuscript for content. S. Wiebe: study design, obtaining funding, revising manuscript for content. G.Y. Zou: study design, obtaining funding, supervision of statistical analysis, revising manuscript for content.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jones MW. Consequences of epilepsy: why do we treat seizures? Can J Neurol Sci 1998;25:S24–S26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schachter SC. Epilepsy: quality of life and cost of care. Epilepsy Behav 2000;1:120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devinsky O, Westbrook L, Cramer J, Glassman M, Perrine K, Camfield C. Risk factors for poor health-related quality of life in adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1999;40:1715–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jakovljevic MB, Jankovic SM, Jankovic SV, Todorovic N. Inverse correlation of valproic acid serum concentrations and quality of life in adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2008;80:180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elliott IM, Lach L, Smith ML. I just want to be normal: a qualitative study exploring how children and adolescents view the impact of intractable epilepsy on their quality of life. Epilepsy Behav 2005;7:664–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sabaz M, Cairns DR, Lawson JA, Bleasel AF, Bye AM. The health-related quality of life of children with refractory epilepsy: a comparison of those with and without intellectual disability. Epilepsia 2001;42:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffiths SY, Sherman EM, Slick DJ, Eyrl K, Connolly MB, Steinbok P. Postsurgical health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children following hemispherectomy for intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 2007;48:564–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sabaz M, Lawson JA, Cairns DR, et al. The impact of epilepsy surgery on quality of life in children. Neurology 2006;66:557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller V, Palermo TM, Grewe SD. Quality of life in pediatric epilepsy: demographic and disease-related predictors and comparison with healthy controls. Epilepsy Behav 2003;4:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys. In The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sabaz M, Lawson JA, Cairns DR, et al. Validation of the quality of life in childhood epilepsy questionnaire in American epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Behav 2003;4:680–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE., Jr. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User's Manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Speechley KN, Sang X, Levin S, et al. Assessing severity of epilepsy in children: preliminary evidence of validity and reliability of a single-item scale. Epilepsy Behav 2008;13:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Camfield C, Breau L, Camfield P. Impact of pediatric epilepsy on the family: a new scale for clinical and research use. Epilepsia 2001;42:104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. International League Against Epilepsy Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1981;22:489–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. International League Against Epilepsy Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1989;30:389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smilkstein G. The Family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract 1978;6:1231–1239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA. FIRM: Family Inventory of Resources for Management. In: Family Assessment: Resiliency, Coping and Adaptation Inventories for Research and Practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin Publishers; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austin JK, Risinger MW, Beckett LA. Correlates of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1992;33:1115–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA. FILE: Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes. In: Family Assessment: Resiliency, Coping and Adaptation Inventories for Research and Practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin Publishers; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD. Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:861–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic Regression: a Self-Learning Text, 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geerts A, Arts WF, Stroink H, et al. Course and outcome of childhood epilepsy: a 15-year follow-up of the Dutch Study of Epilepsy in Childhood. Epilepsia 2010;51:1189–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Modi AC, Ingerski LM, Rausch JR, Glauser TA. Treatment factors affecting longitudinal quality of life in new onset pediatric epilepsy. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:466–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turky A, Beavis JM, Thapar AK, Kerr MP. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with epilepsy: an investigation of predictive variables. Epilepsy Behav 2008;12:136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodenburg R, Meijer AM, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family factors and psychopathology in children with epilepsy: a literature review. Epilepsy Behav 2005;6:488–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fastenau PS, Shen J, Dunn DW, Perkins SM, Hermann BP, Austin JK. Neuropsychological predictors of academic underachievement in pediatric epilepsy: moderating roles of demographic, seizure, and psychosocial variables. Epilepsia 2004;45:1261–1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Austin JK, Perkins SM, Johnson CS, et al. Self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with seizures: relationships with neuropsychological functioning and family variables over time. Epilepsia 2010;51:2074–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yong L, Chengye J, Jiong Q. Factors affecting the quality of life in childhood epilepsy in China. Acta Neurol Scand 2006;113:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferro MA, Avison WR, Campbell MK, Speechley KN. The impact of maternal depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy: a prospective study of family environment as mediators and moderators. Epilepsia 2011;52:316–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barclay-Goddard R, Epstein JD, Mayo NE. Response shift: a brief overview and proposed research priorities. Qual Life Res 2009;18:335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eiser C, Morse R. Quality-of-life measures in chronic diseases of childhood. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferro MA, Avison WR, Campbell MK, Speechley KN. Do depressive symptoms affect mothers' reports of child outcomes in children with new-onset epilepsy? Qual Life Res 2010;19:955–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, et al. The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res 1998;7:387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baca CB, Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Vassar SD, Berg AT. Differences in child versus parent reports of the child's health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy and healthy siblings. Value Health 2010;13:778–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Speechley KN, Levin SD, Wiebe S, Blume WT. Referral patterns of family physicians may allow population-based incidence studies of childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia 1999;40:225–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.