Abstract

Studies examining the effect of coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) on the HCV-specific immune response in acute HCV infection are limited. This study directly compared acute HCV-specific T-cell responses and cytokine profiles between 20 HIV/HCV-coinfected and 20 HCV-monoinfected subjects, enrolled in the Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC), using HCV peptide enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) and multiplex in vitro cytokine production assays. HIV/HCV coinfection had a detrimental effect on the HCV-specific cytokine production in acute HCV infection, particularly on HCV-specific interferon γ (IFN-γ) production (magnitude P = .004; breadth P = .046), which correlated with peripheral CD4+ T-cell counts (ρ = 0.605; P = .005) but not with detectable HIV viremia (ρ = 0.152; P = .534).

Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) has detrimental effects on HCV disease progression, including increased HCV RNA levels, promotion of viral persistence in primary infection, and faster progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. HIV/HCV coinfection has also been associated with a significant reduction in the response to HCV antiviral treatment [2]. Individuals with primary HCV infection who undergo spontaneous clearance have an initial robust CD4+ helper cell response, whereas those who develop viral persistence have a poorer response, which diminishes overtime [3]. However, studies addressing the impact of coinfection on the effector function of HCV-specific T cells in acute HCV infection are limited.

A small study by van den Burg et al reported a valuable role for HCV-specific CD4+ T-cell responses targeting HCV nonstructural (NS) proteins in reduction of HCV RNA (n = 2) and resolution of HCV (n = 1) in subjects with acute HIV/HCV coinfection [4]. Schnuriger et al demonstrated a similar finding, wherein HCV-specific proliferative responses (particularly against NS4) were associated with lower HCV RNA levels and spontaneous clearance of HCV in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects [5]. Interestingly, IFN-γ responses were not associated with HCV clearance or with CD4+ T-cell counts [5]. More recently Thomson et al reported a trend for spontaneous clearance of acute HCV infection, in HIV-positive men, associated with higher CD4+ T-cell counts and stronger T-cell responses within the first 3 months of HCV infection [6].

Even fewer studies, have directly compared acute HCV-specific T-cell responses between HIV/HCV coinfection and HCV monoinfection. Danta et al demonstrated a lower frequency of HCV-specific IFN-γ production in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects compared with internationally recruited HCV-monoinfected controls, although there was no difference in the magnitude of IFN-γ production between the cohorts [7].

These studies raise the question of whether the detrimental effects of HIV/HCV coinfection on HCV clearance could be attributed to a lack of CD4+ T-cell help, which is important in the generation and maintenance of CD8+ T-cell responses [8], to an altered cytokine environment, or both. Our objective was to determine whether the magnitude and breadth of the HCV-specific cellular immune responses in acute HCV infection is affected by HIV/HCV coinfection by directly comparing HCV-specific T-cell responses in subjects with acute HCV infection with or without HIV infection, recruited simultaneously within the Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The ATAHC was a multicenter, prospective cohort study of the natural history and treatment of recent HCV infection (2004–2007 [9]). All study participants provided written informed consent. Both HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals were eligible for enrollment. The study protocol was approved by St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (primary study committee) and local study sites. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov registry (NCT00192569) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH)/WHO Good Clinical Practice standards guidelines.

Virological Testing

HCV RNA assessment was performed with a qualitative HCV-RNA assay (TMA assay, Versant; detection limit, 10 IU/mL); if HCV RNA was detected, a quantitative assay was performed (Versant HCV RNA 3.0; detection limit, 615 IU/mL). HCV genotypin (Versant LiPa2) was performed on participants with detectable HCV RNA at screening. Interleukin 28B genotyping was performed as described elsewhere [10].

HCV Peptides

Immunological assays were performed using peptides (18 amino acids in length, overlapping by 11 amino acids) based on the HCV genotype 1a sequence (National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS Reference and Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; HCV 1a H77 Peptides) covering the entire HCV coding region. Peptides were used at 1 µg/mL, grouped into 10 pools for ELISPOT assays (core, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4a, NS 4b, NS5a, NS5b) and 3 pools for multiplex in vitro cytokine assays (core-p7, NS2–3, NS4–5) owing to restrictions in available cell number.

ELISPOT IFN-γ and Interleukin 2 Assays

ELISPOT assays were performed largely following the manufacturer's protocol (Mabtech) with the exception of the coating antibody concentration (5 µg/mL). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were added to triplicate wells (1 × 105/well; described elsewhere [11]), and plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide for 24 hours. Spot-forming cells (SFCs) were evaluated using an automated ELISPOT reader (AID version 3.2.3). Positive responses were at least twice background levels with a threshold of ≥50 SFCs/106 PBMCs, previously determined using 15 seronegative blood donors [11].

Multiplex In Vitro Cytokine Production

Multiplex in vitro Th1 and Th2 cytokine assays (interleukin 2 [IL-2], interleukin 4, interleukin 5, interleukin 10 [IL-10], interleukin 12p70, interleukin 13, IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) were performed largely according to the manufacturer's protocol (Bio-plex Human Cytokine Assay; Bio-Rad), described elsewhere [11]. Briefly, PBMCs were cultured in 384-well microplates (7.5 × 105/well), stimulated with HCV peptide pools or controls. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours, before 50 µL of supernatant was assayed in a bead-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric analyses were performed using Mann-Whitney tests and Fisher exact test or χ2 test for categorical analyses, as appropriate. Correlations were performed with Spearman's statistic (Stata/IC 10.0 for Windows). A significance level of .05 was used.

RESULTS

Study Subjects

A total of 163 participants were enrolled in ATAHC; 69% were HCV monoinfected (113 of 163), and 31% HIV/HCV coinfected (50 of 163) [9]. The first 20 HIV/HCV-coinfected and HCV-monoinfected subjects enrolled with acute HCV infection (≤26 weeks; HCV RNA positive at screening) were included in this study. Immunological assays were performed on screening samples before the initiation of HCV treatment.

The cohorts were similar in HCV clinical characteristics and demographics, except that the HIV/HCV-coinfected cohort had more male subjects (P = .020) and was older (P = .026) (Tables 1–3). Despite trends toward different modes of HCV acquisition (sexual exposure, 8 of 20 coinfected vs 2 of 20 monoinfected subjects [P = .041]; injection drug use, 8 of 20 coinfected vs 17 of 20 monoinfected subjects [P = .041]), this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .054).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics From 20 Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Infected Subjects With Acute Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) at Screening

| Subject (Study ID) | Age, y | Sex | HCV Genotype | Duration of HCV Infection, wk | HCV Clinical Symptomsa | Mode of HCV Acquisition | HCV RNA, log10 IU/mL | ALT, IU/L | CD4+ T-Cell Count, Cells/mm3 |

HAART During Study | HCV Virological Study Outcomec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen | Nadirb | |||||||||||

| Co1 (101) | 35 | Male | 1a | 10 | Yes (3) | IDU | 4.98d | 52 | 437 | 238 | Yes | Unknown |

| Co2 (102) | 34 | Male | 1a | 16 | Yes (4) | IDU | 6.33 | 1066 | 630 | 448 | No | NR |

| Co3 (113) | 42 | Male | 1a | 6 | Yes (3, 4) | IDU | 5.28d | 630 | 650 | 189 | Yes | SVR |

| Co4 (116) | 36 | Male | 1a | 8 | No | Sexual | 6.75d | 762 | 342 | 291 | Yes | NR |

| Co5 (117) | 43 | Male | 4e | 20 | No | Other | 3.35 | 29 | 840 | 555 | No | Persist |

| Co6 (119) | 55 | Male | 3a | 8 | No | Sexual | 4.83 | 764 | 644 | 292 | Yes | SVR |

| Co7 (120) | 38 | Male | 1a | 9 | No | Sexual | 3.51 | 41 | 840 | 281 | Yes | SVR |

| Co8 (126) | 42 | Male | 1a | 6 | Yes (1, 2) | IDU | 6.57d | 2840d | 924 | 598 | Yes | SVR |

| Co9 (127) | 23 | Male | 1a | 25 | Yes (2) | Sexual | 6.42 | 333 | 828 | 880 | No | NR |

| Co10 (626) | 47 | Male | 3a | 7 | No | IDU | 5.91d | 334 | 400 | 361 | Yes | SVR |

| Co11 (628) | 49 | Male | 1a | 12 | No | Sexual | 3.83d | 315 | 642 | 56 | Yes | NR |

| Co12 (633) | 32 | Male | 1a | 17 | Yes (1) | IDU | 3.93 | 124 | 791 | 482 | No | SVR |

| Co13 (635) | 36 | Male | 3a | 25 | Yes (3–5) | Sexual | 1.00–2.97 | 217 | 506 | 8 | Yes | Clear |

| Co14 (636) | 39 | Male | 3a | 17 | Yes (1–3, 5) | Sexual | 5.75d | 2936d | 554 | 260 | Yes | SVR |

| Co15 (644) | 29 | Male | 1a | 16 | No | IDU | 1.00–2.97 | 145 | 391 | 312 | No | SVR |

| Co16 (648) | 46 | Male | 1b | 15 | Yes (1–3) | IDU | 6.03 | 181 | 565 | 54 | No | SVR |

| Co17 (810) | 44 | Male | 2a/c | 26 | No | Sexual | 6.51d | 112 | 340 | 203 | Yes | Reinfect |

| Co18 (2402) | 45 | Male | 1a | 15 | Yes (1–5) | Other | 3.44d | 82 | 1090 | 10 | Yes | Clear |

| Co19 (2403) | 52 | Male | 1b | 16 | Yes (3) | IDU | 5.61 | 420 | 510 | 476 | No | SVR |

| Co20 (2602) | 44 | Male | 1a | 8 | No | IDU | 5.25 | 560d | 510 | 342 | Yes | NR |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HAART, highly active antiretroviral treatment; ID, identification number; IDU, injection drug use; NR, nonresponder; SVR, sustained virological responder.

a Specific clinical symptoms are indicated numerically: 1, jaundice; 2, nausea; 3, abdominal pain; 4, fever; 5, hepatomegaly.

b Nadir CD4+ T-cell counts were defined as the lowest CD4+ T-cell count after HIV infection, obtained historically from the patient's treating physician and/or clinical notes.

c Outcomes were defined as follows: clear, untreated subject with HCV clearance; NR, treated subject with viral persistence; persist, untreated subject with viral persistence; reinfect, subject who was reinfected; SVR, treated subject with HCV clearance who remained HCV negative; unknown, subject lost to follow-up before a study outcome was established.

d Peak RNA and ALT levels.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics From 20 Subjects With Acute Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Monoinfection at Screening

| Subject (Study ID) | Age, y | Sex | Genotype | Duration of HCV infection, wk | HCV Clinical Symptomsa | Risk Factor | HCV RNA, log10 IU/mL | ALT, IU/L | HCV Virological Study Outcomeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoinfection | |||||||||

| Mo1 (104) | 30 | Female | 2a/c | 12 | Yes (2) | Sexual | 3.04 | 223 | Persist |

| Mo2 (106) | 25 | Male | 3a | 7 | No | IDU | 5.03c | 1235c | Clear |

| Mo3 (109) | 34 | Male | 1a | 14 | No | IDU | 4.76 | 281c | NR |

| Mo4 (110) | 17 | Male | 2 | 9 | Yes (3) | IDU | 4.68 | 468c | NR |

| Mo5 (118) | 42 | Male | 1a | 15 | Yes (3, 4) | Sexual | 6.05c | 355c | SVR |

| Mo6 (201) | 48 | Male | 3a | 17 | No | IDU | 6.40 | 155c | Persist |

| Mo7 (202) | 43 | Male | 3a | 18 | No | IDU | 4.40c | 45c | SVR |

| Mo8 (205) | 38 | Male | 1a/3a | 24 | No | IDU | 4.55 | 129 | SVR |

| Mo9 (302) | 47 | Male | 1 | 21 | No | Other | 3.59c | 59 | SVR |

| Mo10 (307) | 28 | Female | 1a/b | 11 | No | IDU | 3.46 | 39 | Clear |

| Mo11 (308) | 25 | Male | 1 | 14 | Yes (1–3) | IDU | 1.00–2.97c | 104c | Clear |

| Mo12 (502) | 51 | Male | 1b | 19 | Yes (1–3) | IDU | 5.80 | 353c | SVR |

| Mo13 (604) | 36 | Male | 3a | 7 | Yes (1–5) | IDU | 6.02c | 1302c | SVR |

| Mo14 (606) | 18 | Female | 3a | 22 | Yes (2, 4) | IDU | 5.84 | 273 | NR |

| Mo15 (610) | 45 | Male | 1a | 25 | Yes (1–3) | IDU | 1.00–2.97c | 29 | SVR |

| Mo16 (614) | 24 | Female | 3a | 24 | No | IDU | 4.04 | 139 | Persist |

| Mo17 (639) | 24 | Female | 3a | 24 | Yes (2–4) | IDU | 3.31 | 33 | SVR |

| Mo18 (806) | 23 | Male | 1b | 17 | No | IDU | 5.01 | 486c | SVR |

| Mo19 (1101) | 28 | Male | 3a | 25 | No | IDU | 4.89c | 135c | Reinfect |

| Mo20 (1603) | 35 | Female | 3a | 19 | Yes (1, 2) | IDU | 3.77 | 174 | NR |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ID, identification number; IDU, injection drug use; NR, nonresponder; SVR, sustained virological responder.

a Specific clinical symptoms are indicated numerically: 1, jaundice; 2, nausea; 3, abdominal pain; 4, fever; 5, hepatomegaly.

b Outcomes were defined as follows: clear, untreated subject with HCV clearance; NR, treated subject with viral persistence; persist, untreated subject with viral persistence; reinfect, subject who was reinfected; SVR, treated subject with HCV clearance who remained HCV negative; unknown, subject lost to follow-up before a study outcome was established.

c Peak RNA and ALT levels.

Table 3.

Statistical Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between Cohorts

| Clinical Characteristic | HIV/HCV Coinfection (n = 20) | HCV Monoinfection (n = 20) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 20 (100) | 14 (70) | .020a |

| Female | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 41 (8) | 34 (10) | .026a |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 19 (95) | 17 (85) | .605 |

| Other | 1 (5) | 3 (14) | |

| Mode of HCV acquisition | |||

| IDU | 10 (50) | 1 (85) | .054 |

| Sexual | 8 (40) | 2 (10) | |

| Other | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Estimated duration of infection, wk | |||

| Median (IQR) | 15 (8–17) | 18 (13–23) | .095 |

| Mean (SD) | 14 (6) | 17 (6) | |

| Presentation of recent HCV | |||

| Acute clinical (symptomatic) | 11 (55) | 10 (50) | .137 |

| Acute clinical (ALT >400 IU/mL) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | |

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 2 (10) | 7 (35) | |

| HCV RNA | |||

| Median (IQR), log10 IU/L | 5.26 (3.59–6.26) | 4.62 (3.49–5.61) | .234 |

| <400 000 IU/mL | 11 (55) | 15 (75) | |

| >400 000 IU/mL | 9 (45) | 5 (25) | |

| ALT | |||

| Median (IQR), IU/L | 324 (115–729) | 164 (70–354) | .239 |

| <100 IU/L | 5 (24) | 6 (29) | |

| >100 IU/L | 16 (76) | 15 (71) | |

| HCV genotype | |||

| 1 | 14 (70) | 8 (40) | .100 |

| 2 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | |

| 3 | 4 (20) | 9 (45) | |

| 4 | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| IL-28B genotypeb rs8099917 | |||

| TT | 13 (65) | 10 (50) | .730 |

| GT | 5 (25) | 7 (35) | |

| GG | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| IL-28B genotype rs12980275 | |||

| AA | 9 (45) | 9 (45) | 1.000 |

| GA | 9 (45) | 8 (40) | |

| GG | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| IL-28B genotype rs12989860 | |||

| CC | 10 (50) | 7 (35) | 1.000 |

| CT | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | |

| TT | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; IL-28B, interleukin 28 B; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated, data represent No. (%) of subjects.

a Boldface P values indicate positive P values.

b Favorable IL-28 genotypes are in boldface type. Percentages of IL-28B genotype do not add up to 100% because of untypeable subjects in each cohort.

In the HIV/HCV-coinfected cohort, 60% were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) at screening, 91% of whom had an HIV viral load (VL) of ≤50 copies/mL (median HIV RNA level, 50 copies/mL; interquartile range [IQR], 50-50). Of those not receiving HAART, the median HIV VL was 18 318 copies/mL (IQR, 1576–58 325 copies/mL). The median CD4+ T-cell count was 597 cells/mm3 (IQR, 454–818 cells/mm3); 75% of subjects had CD4+ T-cell counts >500 cells/mm3, and none <300 cells/mm3 (Table 1). The nadir CD4+ T-cell count was <200 cells/mm3 in 5 subjects and 200–350 cells/mm3 in 8.

HCV-Specific IFN-γ and IL-2 ELISPOT Responses

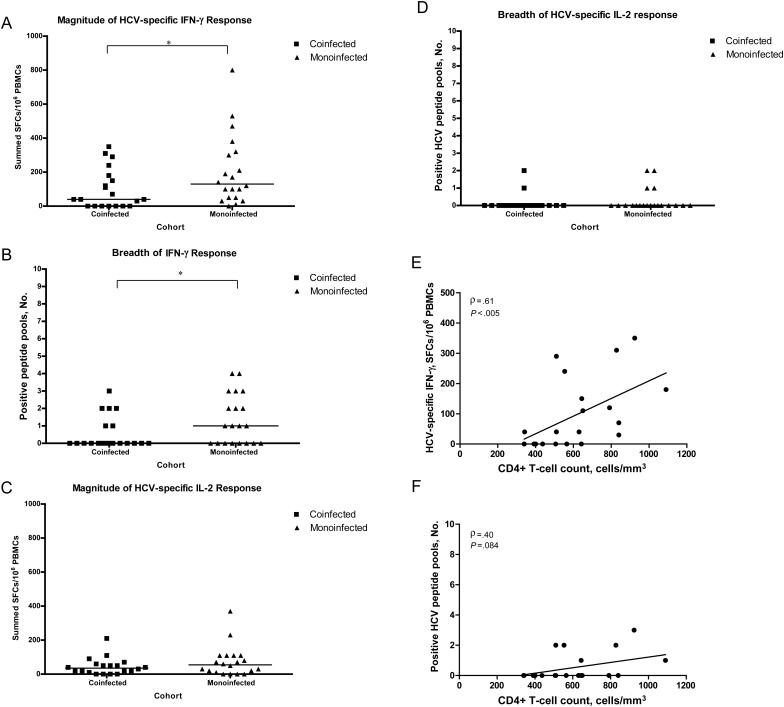

Fewer HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects (6 of 20) had detectable HCV-specific IFN-γ responses compared with HCV-monoinfected subjects (12 of 20; P = .055). These responses were significantly lower in magnitude (mean, 98 ± 116 SFCs for coinfected vs 205 ± 207 SFCs for monoinfected subjects; P = .042) and breadth (median, 0 pools positive for coinfected vs 1 pool for monoinfected subjects; P = .046) (Figure 1A and B); the magnitude was also lower for individual peptide pools (NS2, P = .037; NS4b, P = .030; NS5b, P = .024).

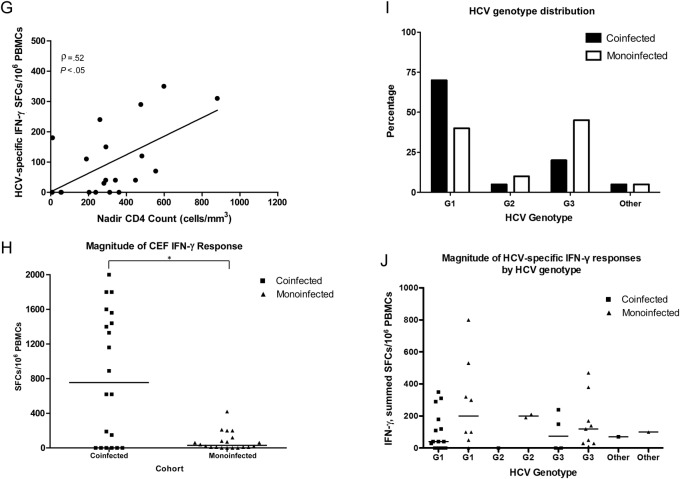

Figure 1.

Magnitude and breadth of HCV-specific interferon γ (IFN-g) and interleukin 2 (IL-2) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay responses to 10 HCV peptide pools (core, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5a, and NS5b) from the screening time point in subjects coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and HCV (n = 20) or monoinfected with HCV (n = 20). A, HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects had significantly fewer HCV-specific IFN-γ–producing cells at screening (black squares) than HCV-monoinfected subjects (black triangles) (range, 0–350 vs 0–800 summed spot-forming cells [SFCs]/106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMCs], respectively; Mann–Whitney test, P = .042, ). B, HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects also had a significantly lower breadth of HCV-specific IFN-γ responses at screening than HCV-monoinfected subjects (median, 0 vs 1 pool positive, respectively; P = .046). C, HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects had lower HCV-specific IL-2 responses at screening than HCV-monoinfected subjects (range, 0–210 vs 0–370 summed SFCs/106 PBMCs, respectively; P = 0.294). D, The breadth of IL-2 responses was similar in the 2 cohorts (median, 0 pools positive for both; P = .383). For A–D, each square or triangle represents an individual subject's response, and the horizontal black lines represent median responses; *P < .05. E, Correlation of HCV-specific IFN-γ cytokine production with CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects from the ELISPOT assay at screening. High-magnitude IFN-γ production was significantly correlated with CD4+ T-cell counts (Spearman correlation ρ = 0.61; P = .005). F, A similar trend was seen for broad IFN-γ responses associated with higher CD4+ T-cell counts (ρ = 0.40 P = .084). G, HCV-specific IFN-γ cytokine production from the ELISPOT assay at screening also correlated with nadir CD4+ T-cell counts in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects (Spearman correlation for IFN-γ magnitude, ρ = 0.52 P = .020). H, IFN-γ responses to non-HCV antigens, gytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and flu virus peptides were significantly higher in coinfected subjects than in monoinfected subjects (range, 0–2000 vs 0–420 SFCs/106 PBMCs, respectively; Mann-Whitney test, P = .022, ). *P < .05 I, Distribution of HCV genotype between cohorts. There was no significance difference in the distribution of genotypes between the cohorts (Fisher exact test, P = .285), nor between the number of genotype 1 subjects in each cohort (Fisher exact test, P = .100). J, Although the HIV/HCV-coinfected cohort included more genotype 1 subjects, the magnitude of IFN-γ responses was lower in this cohort. There was no significant difference in HCV-specific cytokine production between genotype 1 and non–genotype 1 subjects in either cohort (P > .500).

A lower magnitude of HCV-specific IL-2 responses was also detected in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects (mean, 44 ± 49 SFCs for coinfected vs 74 ± 89 SFCs for monoinfected subjects) (Figure 1C), with similar breadth between the 2 cohorts (median, 0 pools positive) (Figure 1D). The specificity of the IL-2 response was directed to E2, NS3, and NS4a/b.

The IFN-γ responses in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects were lower in magnitude and breadth despite the greater number of genotype 1 subjects in this cohort (70% vs 40% for subjects with HCV monoinfection); there were no significant difference in HCV-specific cytokine production between genotype 1 and non–genotype 1 subjects in either cohort (P > .500) (Figure 1I and J).

Interestingly, IFN-γ responses to non-HCV antigens were significantly higher in the HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects (mean cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and flu virus [CEF] peptide response, 828 ± 744 SFCs) than in HCV-monoinfected subjects (mean CEF, 77 ± 107 SFCs; P = .022) (Figure 1H), with similar high-magnitude Th1 responses to anti-CD3 and PHA in both cohorts (P > .150; all >1000 SFCs/106 PBMCs). This indicated that the difference in cytokine production between cohorts was HCV specific.

HCV-Specific Multiplex In Vitro Cytokine Production

HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects had a lower magnitude of Th1 and Th2 HCV-specific cytokine production from PBMCs than HCV-monoinfected subjects, with mean levels of IL-10 and GM-CSF significantly lower in coinfection (IL-10, 139 ± 110 pg/mL; GM-CSF, 25 ± 74 pg/mL) than in monoinfection (IL-10, 532 ± 648 pg/mL, GM-CSF, 88 ± 114 pg/mL; P < .01) (Supplementary Figure 1). Cytokine responses to non-HCV antigens were similar in both cohorts (P > .05).

Cytokine Correlations With Clinical Parameters

There were no significant correlations between the magnitude or breadth of cytokine production and HCV RNA level, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, age, or interleukin 28B genotype in either group (Spearman P > .05), with the exception of GM-CSF levels, which were positively correlated with ALT levels in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects (ρ = 0.466; P = .038).

In the HIV/HCV-coinfected group, screening CD4+ T-cell counts were positively correlated with HCV-specific IFN-γ responses (ELISPOT IFN-γ magnitude, ρ = 0.605 P = .005; IFN-γ breadth, ρ = 0.613 P = .004), as were nadir CD4+ T-cell counts (ELISPOT IFN-γ magnitude, ρ = 0.52 P = .020) (Figure 1E, F, and H), with a similar trend for IL-2 responses (multiarray ρ = 0.400; P = .080). CD4+ T-cell counts were not correlated with HCV RNA level, HIV VL, ALT level, or levels of non-HCV antigens (P > .05).

HIV VL was not correlated with HCV-specific cytokine production, nor was there any difference in magnitude or breadth of HCV-specific cytokine production between subjects with HIV viremia (>50 copies/mL) or HIV VL ≤50 copies/mL (P > .05).

DISCUSSION

Few studies have investigated the effect of HIV/HCV coinfection on the cytokine production and effector function of HCV-specific T cells in acute HCV infection, and fewer studies have been able to directly compare findings with those in subjects with acute HCV monoinfection. The present study demonstrated that, despite similar HCV disease characteristics, HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects had significantly lower magnitude and breadth of HCV-specific IFN-γ production than HCV-monoinfected subjects. The IFN-γ responses to non-HCV antigens were just as high if not higher in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects, indicating that the reduction in IFN-γ was HCV specific.

This decrease in HCV-specific cytokine responses in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects could be attributed to a reported reduced frequency of HCV-specific CD4+ [12] and CD8+ T cells [13] in the periphery of HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects. Interestingly, our study showed a positive correlation between CD4+ T-cell counts and the magnitude of HCV-specific IFN-γ production in HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects, suggesting that HCV-specific cytokine production is related to the level of immune deficiency.

CD4+ T cells play a vital role in viral clearance through the direct activation of macrophages, dendritic cells, and antigen-specific B cells and the cytokine-dependent activation of CD8+ T cells [14]. Cytokines produced largely by CD4+ T cells, such as IL-2, are required for sustained expansion of CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T-cell help is required for the activation and maintenance of CD8+ T-cell responses [8]. Thus, the reduction in CD4+ T cells in HIV/HCV coinfection may contribute to the detrimental effects of coinfection on HCV disease progression.

It is unclear whether a decline in the total number of CD4+ cells in HIV/HCV coinfection is associated with a reduction in the number of HCV-specific T cells or the magnitude of the HCV-specific cytokine response. In chronic HIV/HCV, Harcourt et al did not find a correlation between CD4+ T-cell count and HCV-specific IFN-γ production [12], whereas Kim et al demonstrated peripheral CD4+ T-cell counts correlated with the magnitude and breadth of the HCV-specific CD8+ IFN-γ+ T-cell response [15]. Another hypothesis for the reduction in HCV-specific T cells in the periphery, which we cannot discount, is that they may be compartmentalized in the infected liver [15].

Our study is the first to illustrate a positive correlation between HCV-specific IFN-γ production and CD4+ T-cell counts in acute HIV/HCV coinfection. The majority of our HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects had CD4+ T-cell counts within the normal range (>500 cells/mm3). This indicates a possible impairment in CD4+ T-cell function in acute HIV/HCV coinfection, wherein the loss of CD4+ T-cell help has detrimental effects on the generation of effector and memory CD8+ T-cell responses and the production of HCV-specific cytokines.

In conclusion, HIV/HCV-coinfected subjects showed an association with lower magnitude and breadth of HCV-specific T-cell responses, particularly Th1 cytokine responses. Interestingly, the HCV-specific IFN-γ response correlated with CD4+ T-cell counts indicating a possible mechanism of impaired priming and proliferation of the CD4+ T cells, potentially reducing proliferation, activation and differentiation of CD8+ T cells. This finding highlights the importance of functional HCV-specific Th1 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells early in HIV/HCV coinfection. An increased understanding of the cytokine environment in acute HIV/HCV coinfection is likely to be important when considering the timing of current treatments to assist clearance of HCV.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

ATAHC Study Group. Protocol Steering Committee members: John Kaldor (Kirby Institute, New South Wales), Gregory Dore (Kirby Institute), Gail Matthews (Kirby Institute), Pip Marks (Kirby Institute), Andrew Lloyd (University of New South Wales [UNSW]), Margaret Hellard (Burnet Institute, Victoria [VIC]), Paul Haber (University of Sydney), Rose Ffrench (Burnet Institute), Peter White (UNSW), William Rawlinson (UNSW), Carolyn Day (University of Sydney), Ingrid van Beek (Kirketon Road Centre), Geoff McCaughan (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital), Annie Madden (Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League, Australian Capital Territory), Kate Dolan (UNSW), Geoff Farrell (Canberra Hospital, Australian Capital Territory), Nick Crofts (Burnet Institute), William Sievert (Monash Medical Centre, VIC), David Baker (407 Doctors). Kirby Institute research staff: John Kaldor, Gregory Dore, Gail Matthews, Pip Marks, Barbara Yeung, Brian Acraman, Kathy Petoumenos, Janaki Amin, Carolyn Day, Anna Doab, Jason Grebely, Therese Carroll. Burnet Institute research staff: Margaret Hellard, Oanh Nguyen, Sally von Bibra. Immunovirology laboratory research staff: Andrew Lloyd, Suzy Teutsch, Hui Li, Alieen Oon, Barbara Cameron (UNSW Department of Pathology); William Rawlinson, Brendan Jacka, Yong Pan (Southern Eastern Area Laboratory Services, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, Australia); Rose Ffrench, Jacqueline Flynn, Kylie Goy (Burnet Institute Laboratory). Clinical site principal investigators: Gregory Dore, St Vincent's Hospital, New South Wales; Margaret Hellard, The Alfred Hospital, Infectious Disease Unit, VIC; David Shaw, Royal Adelaide Hospital, South Australia; Paul Haber, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; Joe Sasadeusz, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC; Darrell Crawford, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Queensland; Ingrid van Beek, Kirketon Road Centre; Nghi Phung, Nepean Hospital; Jacob George, Westmead Hospital; Mark Bloch, Holdsworth House GP Practice; David Baker, 407 Doctors; Brian Hughes, John Hunter Hospital; Lindsay Mollison, Fremantle Hospital; Stuart Roberts, The Alfred Hospital, Gastroenterology Unit, VIC; William Sievert, Monash Medical Centre, VIC; Paul Desmond, St Vincent's Hospital, VIC.

Acknowledgments. The Kirby Institute is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales. Roche Pharmaceuticals supplied financial support for pegylated interferon alfa-2a/ribavirin. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this work of the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Support Program, received by the Burnet Institute.

Disclaimer. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the position of the Australian government.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 15999-01), the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, the NHMRC (Dora Lush PhD scholarship to J. K. F., fellowship to M. H., industry fellowship to R. A. F., and practitioner fellowships to G. J. D., W. D. R., and A. R. L.), and VicHealth (fellowship to M. H.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C in the HIV-infected person. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:197–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung R, Anderson J, Volberding P, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alpha 2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:451–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulze zur Wiesch J, Ciuffreda D, Lewis-Ximenez L, et al. Broadly directed virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses are primed during acute hepatitis C infection, but rapidly disappear from human blood with viral persistence. J Exp Med. 2012;209:61–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Berg CHSB, Ruys TA, Nanlohy NM, et al. Comprehensive longitudinal analysis of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific T cell responses during acute HCV infection in the presence of existing HIV-1 infection. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnuriger A, Dominguez S, Guiguet M, et al. Acute hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients: rare spontaneous clearance correlates with weak memory CD4 T-cell responses to hepatitis C virus. AIDS. 2009;23:2079–89. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330ed24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson EC, Fleming VM, Main J, et al. Predicting spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus in a large cohort of HIV-1-infected men. Gut. 2011;60:837–45. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danta M, Semmo N, Fabris P, et al. Impact of HIV on host-virus interactions during early hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1–9. doi: 10.1086/587843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaech SM, Ahmed R. CD8 T cells remember with a little help. Science. 2003;300:263. doi: 10.1126/science.1084511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dore GJ, Hellard M, Matthews G, et al. Effective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:123–35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grebely J, Petoumenos K, Hellard M, et al. Potential role for interleukin-28B genotype in treatment decision-making in recent hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2010;52:1216–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.23850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn JK, Dore GJ, Hellard M, et al. Early IL-10 predominant responses are associated with progression to chronic hepatitis C virus infection in injecting drug users. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:549–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harcourt G, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Klenerman P. Diminished frequency of hepatitis C virus specific interferon gamma secreting CD4+ T cells in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. Gut. 2006;55:1484–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauer GM, Nguyen TN, Day CL, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-hepatitis C virus coinfection: intraindividual comparison of cellular immune responses against two persistent viruses. J Virol. 2002;76:2817–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2817-2826.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thimme R, Lohmann V, Weber F. A target on the move: innate and adaptive immune escape strategies of hepatitis C virus. Antiviral Res. 2006;68:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim AY, Lauer GM, Ouchi K, et al. The magnitude and breadth of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells depend on absolute CD4+ T-cell count in individuals coinfected with HIV-1. Blood. 2005;105:1170–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.