Abstract

We have demonstrated that ouabain regulates protein trafficking of the Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit and NHE3 (Na/H exchanger, isoform 3) via ouabain-activated Na/K-ATPase signaling in porcine LLC-PK1 cells. To investigate whether this mechanism is species-specific, ouabain-induced regulation of the α1 subunit and NHE3 as well as transcellular 22Na+ transport were compared in three renal proximal tubular cell lines (human HK-2, porcine LLC-PK1, and AAC-19 originated from LLC-PK1 in which the pig α1 was replaced by ouabain-resistant rat α1). Ouabain inhibited transcellular 22Na+ transport due to an ouabain-induced redistribution of the α1 subunit and NHE3. In LLC-PK1 cells, ouabain also inhibited the endocytic recycling of internalized NHE3, but has no significant effect on recycling of endocytosed α1 subunit. These data indicated that the ouabain-induced redistribution of the α1 subunit and NHE3 is not a species-specific phenomenon, and ouabain-activated Na/K-ATPase signaling influences NHE3 regulation.

Keywords: Ouabain, Na/K-ATPase signaling, Na/K-ATPase, NHE3, redistribution

Introduction

Renal sodium handling is a key determinant of long term regulation of blood pressure (1–4). In the kidney, the renal proximal tubules (RPTs) are responsible for more than 60% of the net tubular Na+ reabsorption, mainly through basolateral Na/K-ATPase and apical NHE3. Endogenous CTS (cardiotonic steroids, also known as digitalis-like substances), which were initially classified as specific inhibitors of the Na/K-ATPase and now classified as a new family of steroid hormones, are involved in regulation of blood pressure and renal sodium handling (5–7). Circulating CTS are markedly increased under certain conditions such as salt loading, volume expansion, renal insufficiency, and congestive heart failure (8–10).

The pathophysiological significance of endogenous CTS has been a subject of debate since it was first proposed (11–13). In essence, the Na/K-ATPase inhibitor (endogenous CTS) will rise in response to either a defect in renal Na+ excretion or high salt intake. This increase, while returning Na+ balance toward normal by increasing renal Na+ excretion, also cause increases in blood pressure through acting on vascular Na/K-ATPase (14). Increases in endogenous CTS regulate both renal Na+ excretion and blood pressure through the Na/K-ATPase (7, 14–17).

In porcine RPT LLC-PK1 cells, we have shown that ouabain inhibits active transepithelial 22Na+ transport (from apical to basolateral aspect) via protein trafficking regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (18–20), a process requiring ouabain-activated Na/K-ATPase signaling. This novel regulatory mechanism may contribute to CTS-induced natriuresis, especially in rodents expressing ouabain-resistant Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit (17). In the present study, we investigated if this regulatory mechanism is species-specific by characterizing the effect of ouabain on transcellular 22Na+ flux and redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3. Furthermore, we also investigate the endocytic recycling (reinsertion of endocytosed protein back to plasma membrane) of internalized Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 in LLC-PK1 cells.

Experimental Methods

Chemicals and Antibodies

All reagents, unless otherwise mentioned, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Src kinase inhibitor PP2 was from CalBiochem (San Diego, CA). EZ-Kink sulfo-NHS-ss-Biotin and ImmunoPure immobilized streptavidin-agarose beads were obtained from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against a mixture of peptides from porcine NHE3 was prepared and affinity purified (21). Antibodies against Rab7, integrin-β1 and human NHE3 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibody against the Na/K-ATPase α1-subunit (clone α6F) was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). Monoclonal antibodies against NHE3 (clone 4F5) and early endosome antigen-1 (EEA-1) were from Millipore Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Radioactive rubidium (86Rb+) and sodium (22Na+) were from DuPont NEN Life Science (Boston, MA).

Cell cultures

Human HK-2 cells and pig LLC-PK1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). AAC-19 cells were generated from LLC-PK1 cells as we described previously (22). Briefly, the ouabain-sensitive pig α1 in LLC-PK1 cells was knock-down by siRNA method. To rescue the α1 knock-down cell with ouabain-resistant rat α1 (AAC-19 cells), the α1 siRNA targeted sequence was silently mutated to introduce rat α1 with rat α1 pRc/CMV-α1AAC expression vector. The expression of ouabain-insensitive rat α1 was selected with 3μM ouabain in culture medium since untransfected LLC-PK1 cells are very sensitive to ouabain. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium)/F-12 mixed medium (1:1, vol/vol) for HK-2 or DMEM for LLC-PK1 and AAC-19, with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator. Culture medium was changed daily until confluency. LLC-PK1 cells and AAC-19 cells were serum-starved (in serum-free DMEM medium) for 16–18 h before treatment, and HK-2 cells were changed to medium containing 1% FBS for 16–18 h before treatment. In assays for active transcellular 22Na+ flux, cells were grown on Transwell membrane support to form monolayer, and then treated with ouabain either in the basolateral or apical compartment. Both LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells can be easily grown to monolayers in DMEM medium with 10% FBS. While HK-2 cells are hard to form monolayer with ATCC-recommended Keratinocyte Serum Free Medium, we found that HK-2 cells could be easily grown to monolayer in DMEM/F-12 medium (with 10% FBS) without losing its ouabain sensitivity.

Isolation of early endosome (EE) and late endosome (LE) fractions

EE and LE fractions were fractionated by a sucrose flotation gradient technique as we previously described (18, 19). EE and LE fractions were identified with antibodies against EE marker protein EEA-1 and LE marker protein Rab7, respectively (18, 19). In comparison with whole cell lysates, more than a 10-fold enrichment of these marker proteins was observed in representative endosome fractions as we have previously shown (18).

Cell surface biotinylation

Cell surface biotinylation was conducted as we described before (18, 19). Biotinylated proteins were pulled down with streptavidin-agarose beads, eluted with 2x Laemmli buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, 20% Glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.025% Bromophenol Blue, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8) at 55°C waterbath for 30 minutes, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and then immunoblotted for the Na/K-ATPase α1 and NHE3. The same membrane was also imunoblotted with antibody against integrin-β1 to serve as loading control as described previously (17).

Ouabain-sensitive Na/K-ATPase activity assay (86Rb+ uptake)

For 86Rb+ uptake assay, cells were cultured in 12-well plates and treated with or without different concentrations of ouabain for 15min. Monensin (20 μM), a Na+-clamping agent, was added to the medium prior to the assay to assure that the maximal capacity of active uptake was measured (23). 86Rb+ uptake was initiated by the addition of 1 μCi of 86Rb+ as tracer of K+ to each well, and the reaction was stopped after 15 minutes by washing four times with ice-cold 0.1 M MgCl2. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-soluble 86Rb+ was extracted with 10% TCA and counted. TCA-precipitated cellular protein content was determined and used to calibrate the 86Rb+ uptake. Data were expressed as the percentage of control 86Rb+ uptake.

NHE3 mediated active transepithelial 22Na+ flux and 22Na+ uptake

Active transepithelial 22Na+ flux (from apical to basolateral aspect of the Transwell membrane supports) was performed on monolayers (grown on Costar Transwell culture filter inserts, filter pore size: 0.4 μm, Costar, Cambridge, MA) as described by Haggerty and colleagues (24). Briefly, after ouabain treatment for 1h at the concentration indicated, both apical (upper) and basolateral (lower) compartments were rinsed with ouabain-free DMEM (0% FBS for LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells, and 1% FBS for HK-2 cells). 1 ml DMEM containing 22Na+ (1 μCi/ml) was added to the apical compartment of a filter insert, and the basolateral compartment was filled with 1 ml of DMEM. After 1h, aliquots were removed from the basolateral compartments for scintillation counting. H+-driven 22Na+ uptake were determined as described by Soleimani and colleagues (25). Briefly, the cells grown on 12-well plate were treated with ouabain at the concentration indicated and then washed three times with the Na+-free buffer (in mM, 140 N-methyl-D-glucammonium (NMDG+) Cl, 4 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4). The cells were then incubated for 10 min in the same Na+-free buffer in which 20 mM NMDG+ was replaced with 20 mM NH4+. The uptake was initiated by replacing the NH4+-containing buffer with Na+-free buffer containing 1 μCi/ml 22NaCl+. 22Na+ uptake was stopped after 30 min by washing four times with ice-cold saline. Cell-associated radioactivity was extracted with 1 ml of 1 N sodium hydroxide, quantified by scintillation counting, and calibrated with protein content. In both experimental settings, cells were pretreated with 50 μM amiloride to inhibit amiloride-sensitive NHE1 activity.

Assessment of endocytic recycling of NHE3 and Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit in LLC-PK1 cells

Endocytic recycling of α1 and NHE3 were assessed by the method described by the Moe Laboratory (26). Briefly, two sets of LLC-PK1 cells were biotinylated and quenched at 4°C, and then treated with ouabain (100nM) or vehicle (as control) for 1h at 37°C to induce redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase α1 and NHE3. After rinsing with ice-cold PBS-Ca-Mg (1x PBS with 0.1mM CaCl2 and 1mM MgCl2), un-internalized surface biotinylated proteins were cleaved with 50 mM glutathione-SH (GSH-SH, a reducing agent) at 4°C, and un-reacted free GSH-SH was oxidized by incubation with 30mM iodoacetamide for 10min. At this point, one set of cells was lysed with RIPA buffer to retrieve total internalized intracellular biotinylated α1 and NHE3 with streptavidin-agarose beads. Other set of cells was changed to serum-free DMEM medium and cultured at 37°C to permit further trafficking for 2h with or without 100nM ouabain. Biotinylated proteins that recycled back to cell surface (reinsertion) were cleaved by GSH-SH method again. The remaining intracellular biotinylated proteins after reinsertion were retrieved with streptavidin-agarose beads, which represent the internalized biotinylated α1 and NHE3 that were not reinserted. The difference of the total intracellular α1 and NHE3, before and after reinsertion, represents the α1 and NHE3 that was internalized and then reinserted (endocytic recycling).

Western blot

Equal amounts of total protein were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies (with dilution of 1:2000 for the Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit and 1:1000 dilution for NHE3, in 4% non-fat dry milk in 1x Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20). The same membrane was also imunoblotted with antibodies against integrin-β1 (for surface biotinylation), EEA-1 (for EE fraction) and Rab7 (for LE fraction) to serve as loading controls (data not shown), respectively, as we previously described (17–19). Signal detection was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence super signal kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Multiple exposures were analyzed to assure that the signals were within the linear range of the film. The signal density was determined using Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normality (all data passed) and then subjected to parametric analysis. When more than two groups were compared, one-way ANOVA was performed prior to the comparison of individual groups with an unpaired t-test. Statistical significance was reported at the P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 levels. SPSS software was used for all analysis (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Values are given as mean±S.E.

Results

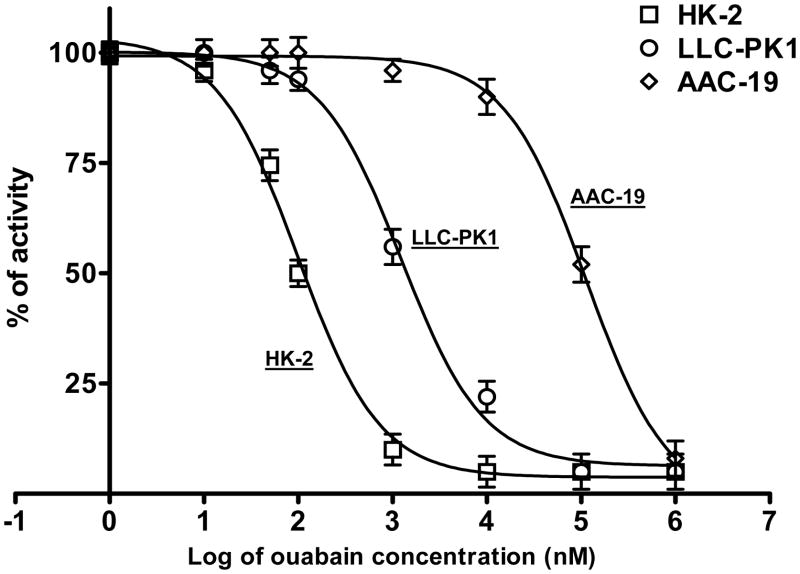

Ouabain-mediated inhibition of the Na/K-ATPase

Ouabain-induced inhibition of the Na/K-ATPase “ion-pumping” activity (ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake) in these RPT cell lines is summarized in Fig 1. The IC50 values are consistent with the established differences of α1 ouabain sensitivity amongst these species (see Discussion). In LLC-PK1 cells with IC50 at 1μM, 100nM ouabain is sufficient to activate the Na/K-ATPase signaling and consequent regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (20). According to the Na/K-ATPase α1 sensitivity to ouabain, we chose ouabain concentrations that are able to activate the Na/K-ATPase signaling for these three cell lines (10nM for HK-2, 100nM for LLC-PK1, and 10μM for AAC-19 cells) without significant inhibition of Na/K-ATPase activity. No significant effect on cell viability was observed when these cells were treated for 1h with ouabain concentrations used that was evaluated by Trypan blue exclusion.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent effects of ouabain (Oua) on Na/K-ATPase activity. The HK-2, LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells were grown in 12-well plates with Transwell membrane support to form monolayer. The Na/K-ATPase activity (ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake) was assayed as described in Experimental Methods. Data were shown as percentage of control, and each point is presented as mean ± S.E. of four sets of independent experiments. Curve fit analysis was performed by GraphPad software.

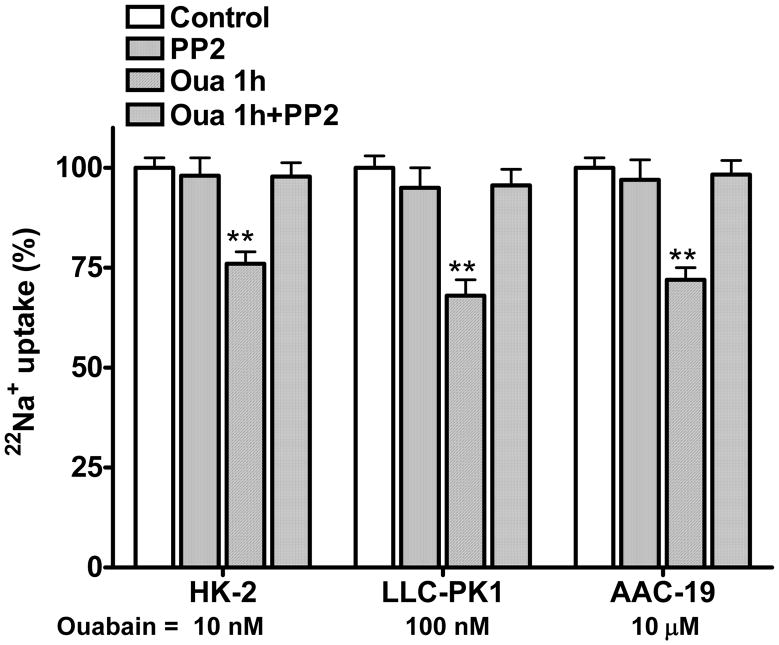

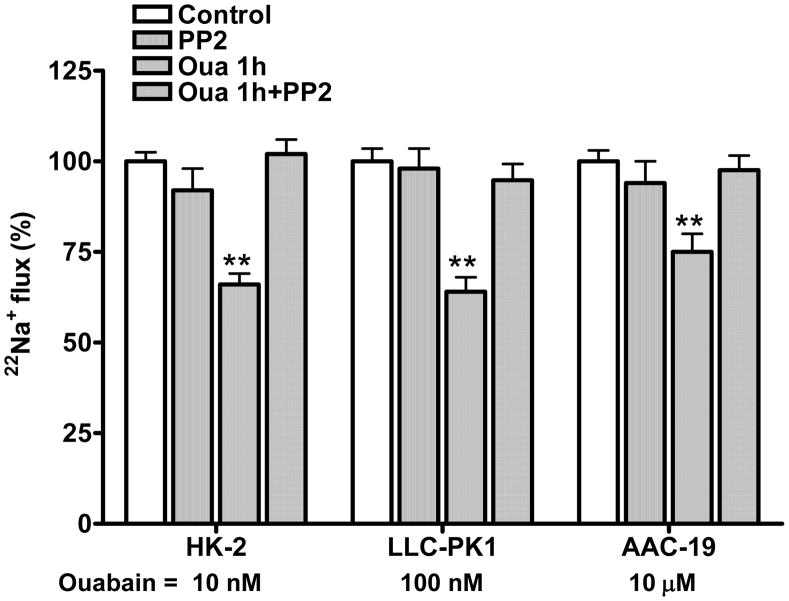

Ouabain-mediated inhibition of transepithelial 22Na+ flux and 22Na+uptake

We have shown that ouabain inhibits transepithelial 22Na+ flux by activating Na/K-ATPase signaling in LLC-PK1 cells (18, 19). To assess if this effect is species-specific, we measured H+-driven 22Na+ uptake and transepithelial 22Na+ flux in these three RPT cell lines. As shown in Fig 2 and 3, when ouabain was added in the basolateral aspect, ouabain inhibited 22Na+ uptake (Fig 2) and active transepithelial 22Na+ flux (Fig 3) in both HK-2 and AAC-19 cells in the same manner as in LLC-PK1 cells. The effect of ouabain on 22Na+ flux and NHE3 activity was largely blunted when these cells were pretreated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1μM for 30 min, at 37 °C). PP2 alone did not show significant effect. No significant inhibition of NHE3 activity was observed in all three cell lines when ouabain was added in the apical aspect (data not shown), suggesting that ouabain-induced regulation of 22Na+ flux and NHE3 activity requires ouabain-activated Na/K-ATPase signaling.

Figure 2.

Ouabain (Oua) inhibits H+-driven 22Na+ uptakes. The HK-2, LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells were grown in 12-well plates to form a monolayer. After treatment with ouabain (1h) and/or PP2 (1μM for 30min), 22Na+ was added and assayed for H+-driven 22Na+ uptake. To determine H+-driven Na+ uptake, cells were first acid loaded in Na+-free buffer with 20 mM NH4Cl and then assayed for 22Na+ uptake. 50 μM amiloride was used to inhibit amiloride-sensitive NHE1 activity. Data are shown as mean ± S.E., percentage of control. n=4. ** p<0.01 compare to Control.

Figure 3.

Ouabain (Oua) inhibits transcellular 22Na+ flux. The HK-2, LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells were grown in 12-well plates with Transwell membrane support to form a monolayer. The cells were treated with ouabain (1h) and/or PP2 (1μM for 30min) in the basolateral or apical aspect. Active transepithelial 22Na+ flux (apical to basolateral) was determined by counting radioactivity in the basolateral aspect at 1 h after 22Na+ addition. 50 μM amiloride was added in the basolateral aspect to inhibit amiloride-sensitive NHE1 activity. Data are shown as mean ± S.E., percentage of control. n=4. ** p<0.01 compare to Control.

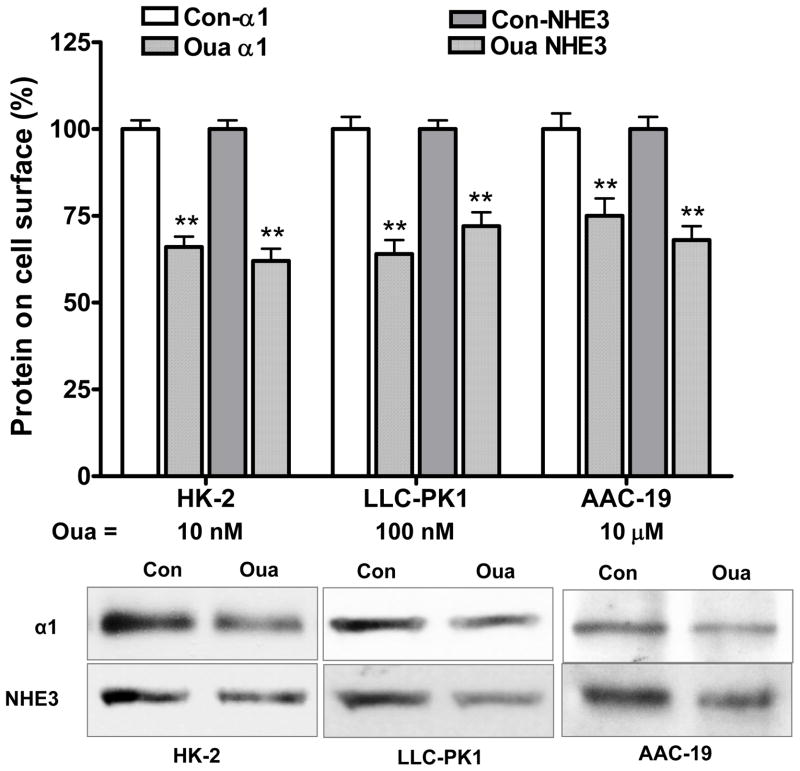

Ouabain-induced protein trafficking of Na/K-ATPase and NHE3

In LLC-PK1 cells, ouabain-induced inhibition of 22Na+ flux is largely due to an ouabain-mediated redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 via Na/K-ATPase signaling. To further test this regulatory mechanism, these three cell lines were treated with or without ouabain to assess the ouabain-induced redistribution. As shown in Fig 4, the ouabain induced redistribution of the α1 subunit and NHE3 was caused by a decrease in cell surface α1 subunit and NHE3 in both HK-2 and AAC-19 cells (as we previously reported in LLC-PK1 cells (18, 19)). Pretreatment with PP2 abolished ouabain-induced redistribution of the α1 subunit and NHE3 (data not shown). As shown in Table 1, ouabain (1h) caused a dose-dependent reduction of cell surface α1 subunit and NHE3. Furthermore, the ouabain-induced reduction of cell surface α1 subunit and NHE3 was closely correlated to ouabain-induced inhibition of transcellular 22Na+ flux and NHE3 activity (Fig. 2 and 3).

Figure 4.

Ouabain (Oua) reduces cell surface expression of the α1 and NHE3. The HK-2, LLC-PK1 and AAC-19 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of ouabain (1h). Biotinylation of cell surface proteins was performed to assess cell surface protein contents. Data are shown as mean ± S.E., percentage of control (Con). n=4. ** p<0.01 compare to control. Insert shows a representative western blot of four separate experiments. Immunoblotting with antibody against integrin-β1 served as loading controls (data not shown).

Table 1.

Ouabain causes a dose-dependent inhibition of transcellular 22Na+ flux, 22Na+ uptake, and surface α1 and NHE3. 22Na+ flux and 22Na+ uptake were measured as described in Experimental Methods. Surface α1 and NHE3 were determined by cell surface biotinylation.

| HK-2 cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouabain (nM) for 1h | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | |

| 22Na+ flux | 100±4.5 | 102.1±3.8 | 81.2±5.2a | 68.5±4.8b | 61.8±5.9 b |

| 22Na+ uptake | 100±5.1 | 98.4±4.2 | 83.6±5.6a | 76.6±6.2 b | 67.8±5.3 b |

| Surface α1 | 100±6.1 | 96.5±6.7 | 84.2±6.2 a | 63.5±7.1 b | 59.7±7.4 b |

| Surface NHE3 | 100±4.5 | 99.2±6.1 | 86.2±6.8 a | 67.3±7.1 b | 69.1±7.9 b |

| LLC-PK1 cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouabain (nM) for 1h | |||||

| 0 | 10 | 25 | 100 | 1,000 | |

| 22Na+ flux | 100±5.2 | 99.1±4.8 | 82.4±7.4a | 65.5±6.8 b | 60.2±8.6 b |

| 22Na+ uptake | 100±5.8 | 95.7±6.7 | 88.3±8.1 a | 64.8±7.2 b | 58.5±7.8 b |

| Surface α1 | 100±7.9 | 97.3±8.1 | 85.6±7.2 a | 65.2±7.7 b | 67.6±8.4 b |

| Surface NHE3 | 100±6.5 | 98.6±8.8 | 83.2±7.4 a | 72.7±6.1 b | 69.3±7.6 b |

| AAC-19 cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouabain (nM) for 1h | |||||

| 0 | 100 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 25,000 | |

| 22Na+ flux | 100±6.2 | 96.3±3.8 | 86.4±7.3 a | 75.5±6.9 b | 68.8±7.6 b |

| 22Na+ uptake | 100±7.2 | 97.8±7.1 | 85.1±8.5 a | 71.6±8.1 b | 65.2±9.6 b |

| Surface α1 | 100±8.2 | 96.5±7.6 | 87.4±8.1 a | 75.2±7.9 b | 67.4±9.1 b |

| Surface NHE3 | 100±9.1 | 94.7±8.7 | 84.8±9.3 a | 69.5±8.8 b | 61.8±9.9 b |

N=3 for each treatment.

p<0.05 compared to controls;

p<0.01 compared to controls.

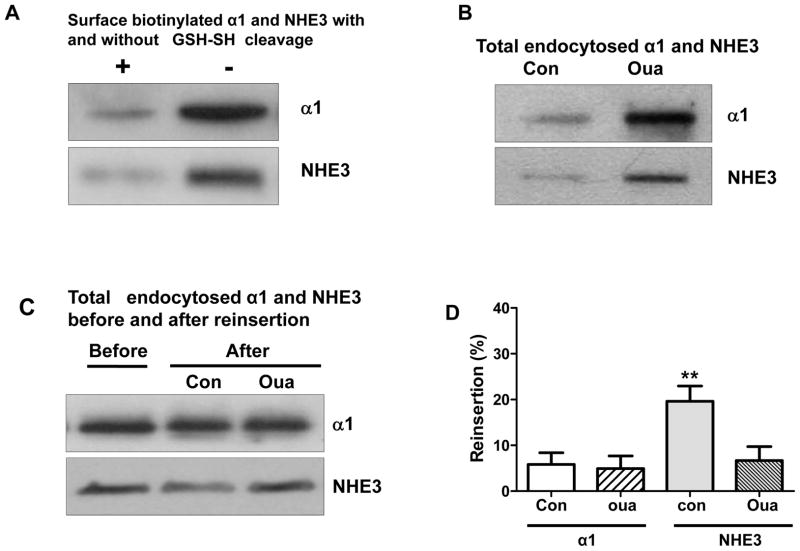

Ouabain-mediated regulation of endocytic recycling of the Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit and NHE3 in LLC-PK1 cells

Endocytic recycling is essential for maintaining the distinction between apical and basolateral membranes in polarized cells, even though the recycling pathways may be redundant (27). It has been shown that ouabain redistributes the Na/K-ATPase into both late endosomes and lysosomes (28), presumably for degradation. To explore the underlying mechanism, we used LLC-PK1 cells to assess endocytic recycling of the α1 subunit and NHE3. As shown in Fig 5A, GSH-SH (glutathione-SH, a reducing agent) was able to cleave over 90% of protein-bound biotin. Ouabain (100nM, 1h) accumulated the α1 subunit (control 100±9.6% vs. ouabain 198.3±18.2, n=3, p<0.01) and NHE3 (control 100±8.9% vs. ouabain 187.4±16.5, n=3, p<0.01) in intracellular compartments (Fig 5B) after cleavage of surface protein-bound biotin with GSH-SH method. After 2h-period of recycling of internalized biotinylated proteins, recycled biotinylated proteins were cleaved again with GSH-SH. The total intracellular biotinylated α1 and NHE3 after recycling, which represent un-recycled biotinylated α1 and NHE3, are shown in Fig 5C. The reinsertion (endocytic recycling) was presented as the difference of the total intracellular α1 and NHE3 before and after reinsertion (Fig 5D). The present data indicate that ouabain treatment not only induced NHE3 redistribution, but it also inhibited the endocytic recycling of NHE3. Interestingly, the endocytic recycling of the α1 subunit was not significantly affected by ouabain. These observations suggested that, while most of the internalized α1 was destined for degradation, at least part of internalized NHE3 was recycled back to cell membrane surface. Despite the lack of microvilli in cultured renal proximal tubular cells (29), our observation is reminiscent of the model of NHE3 moving along the microvilli structure (30).

Figure 5.

Ouabain (Oua) inhibites endocytic recycling of NHE3 in LLC-PK1 cells. The experiments were performed as described in Experimental Methods. (A) Determination of GSH-cleavage efficiency. Cell surface proteins were biotinylated and applied with or without GSH cleavage procedure. (B) Retrieval of total internalized biotinylated α1 and NHE3 after treatment with or without ouabain (100nM, 1h) and GSH cleavage. (C) Assessment of the effect of ouabain on reinsertion. (D) The graph bars represented reinsertion of endocytosed α1 and NHE3, the difference of total endocytosed α1 and NHE3 before and after resinsertion procedure. n=3. **, p<0.01.

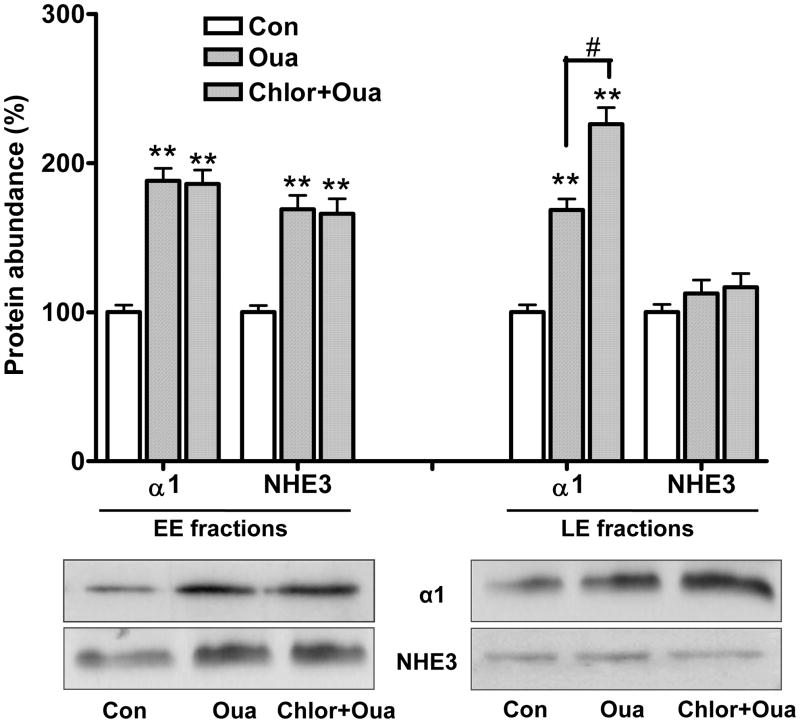

To further explore the destination of the α1 subunit and NHE3, we determined the protein content of these two transporters in EE and LE fractions in response to ouabain. As shown in Fig. 6, ouabain treatment (100nM, 1h) stimulated accumulation of both α1 and NHE3 in EE fractions. However, ouabain significantly accumulated α1, but not NHE3 in LE fractions. The NHE3 protein content in LE fractions was not significantly increased after ouabain treatment, even in the presence of the lysosomotropic weak base agent chloroquine (0.2 mM, pretreated for 2h) which inhibits degradation by the lysosomal pathway. On the other hand, pretreatment with chloroquine caused a further accumulation of the α1 subunit in LE fractions in response to ouabain, suggesting that the endocytosed α1 subunit, but not NHE3, is degraded through the LE-lysosome pathway.

Figure 6.

Ouabain (Oua) accumulates the Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit, but not NHE3 in late endosome in LLC-PK1 cells. LLC-PK1 cells were treated with or without ouabain (100nM for 1h), with or without pretreatment of chloroquine (Chlor, 0.2 mM, pretreated for 2h). Early endosome (EE) and late endosome (LE) fractions were isolated at the end of ouabain treatment. Equal amount of proteins (25 μg) was used to determine protein contents of the α1 and NHE3 by western blot analysis. n=4. ** p<0.01 compared to controls from EE and LE, respectively. # p<0.01, comparison of α1 subunit in LE fraction with or without chloroquine pretreatment. Insert shows a representative western blot of four separate experiments. Immunoblotting with antibodies against EEA-1 (for EE fractionation) and Rab7 (for LE fractionation) served as loading controls, respectively (data not shown).

Discussion

The renal tubular Na/K-ATPase comprises a final site for the regulation of renal sodium transport by many factors (31). Our recent work indicates that ouabain is one of these factors that act via a coordinated regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 through Na/K-ATPase signaling (17–20). In the present study, we have investigated whether this ouabain mediated regulatory model is species-specific. Our present study indicated that ouabain-induced regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 is not species-specific. First, ouabain was able to inhibit the active transepithelial 22Na+ flux in these three cell lines. This effect was largely prevented by blocking c-Src activation with PP2 pretreatment. Secondly, ouabain-induced redistribution and reduction of the cell surface Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 contributed to the inhibition of active 22Na+ flux. Third, the effect of ouabain on active 22Na+ flux was only observed when ouabain was applied in the basolateral, but not in the apical aspect. Fourth, the ouabain-induced reduction of the cell surface α1 subunit contributed to the ouabain-induced inhibition of 22Na+ flux and 22Na+ uptake. Taken together, these observations suggest that the ouabain-induced regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 is not species-specific, and may be explained if the Na/K-ATPase is the functional receptor for ouabain-induced regulation.

Activation of c-Src is critical in the ouabain-activated Na/K-ATPase signaling and redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (18–21, 32). When compared with HK-2 and LLC-PK1 cells, a higher concentration of ouabain was needed to regulate activity and redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 in AAC-19 cells expressing native pig NHE3 and rat α1. This is consistent with the established differences in ouabain sensitivity of the α1 subunit as well as ouabain-stimulated c-Src activation between these two cell lines (22). It is well known that there are large differences in sensitivity of the Na/K-ATPase to ouabain based on α isoforms and species (33–35). Specifically, the rodent α1 is far less sensitive than pig, dog, or human α1. Higher concentrations of ouabain were required to activate Na/K-ATPase signaling in rodents, compared to other species (22, 36–39). We have also shown that a higher concentration of ouabain (10μM) is needed to activate c-Src in isolated renal proximal tubules of Dahl salt-resistant rats (17). Most interestingly, different natriuretic responses were observed between transgenic mice expressing ouabain-sensitive α1 and wild-type mice expressing ouabain-resistant α1(16) in which the ouabain binding site of the α1 subunit plays a critical role (40). As shown in Table 1, the ouabain sensitivity of the α1 subunit influenced the ouabain-induced inhibition of 22Na+ flux as well as surface reduction of the α1 subunit and NHE3. The present study further suggests that species-specific α1 sensitivity to ouabain might explain the species differences in ouabain-induced natriuresis in vivo (7, 10, 16, 41). Considering the high ouabain sensitivity of human α1 subunit, this could be a explanation how pathophysiological circulating CTS might affect renal sodium handling, especially in the view that endogenous ouabain is a natriuretic hormone and has a physiological role in controlling sodium homeostasis in normal rats (7).

After the redistribution of membrane proteins, subsequent intracellular trafficking differs among different endocytosed proteins. Receptor-mediated redistribution is believed to be an effective pathway to reduce cell surface signaling receptors. In our experimental settings, ouabain caused accumulation of the α1 subunit in LE fractions, but failed to affect its endocytic recycling (Fig 5 and 6). This is a reminiscence of the early observation that ouabain caused the redistribution of the Na/K-ATPase into late endosomes and lysosomes (28), suggesting that the endocytosed Na/K-ATPase is most likely degraded in LE/lysosome pathway. On the other hand, the cell surface expression of NHE3 is likely reduced by inhibition of the recycling of internalized NHE3 (Fig 5 and 6). However, the mechanism is not clear. In both cases, we cannot exclude the possibility that both recycling and degradation were affected by ouabain, but the overall observed effect was a balance between these two processes.

Renal Na+ reabsorption through NHE3 plays an important role in salt-sensitivity, as well as in the development and control of sodium homeostasis and blood pressure (42–45). Recently, we have demonstrated that impaired Na/K-ATPase-Src signaling contributes to salt sensitivity in Dahl rats (17). This is consistent with the observation that a high salt diet stimulates redistribution of RPT Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (46). Although the mechanisms are still being elucidated, accumulating evidence supports the notion of coordinated regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (47). It appears that the pathways regulating the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 are numerous and redundant, and CTS-induced coordinated regulation is one of the pathways that occur in response to conditions that cause an increase in endogenous CTS.

In summary, our data indicate that the Na/K-ATPase is the functional receptor for ouabain-induced regulation of the Na/K-ATPase and NHE3 (and thus transcellular Na+ transport), as we previously proposed (20). This regulation is not species-specific, but the species-specific α1 ouabain sensitivity may partially account for the species differences observed in ouabain-induced natriuresis (7, 10, 16, 41). In ouabain-induced trafficking regulation, endocytic recycling of internalized NHE3, but not the α1 subunit, was inhibited by ouabain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Carol Woods her excellent help. Portions of this work were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-105649 (to J.T.), HL-109015 (to Z.X. and J.I.S.) and GM-78565 (to Z.X.).

Literature Cited

- 1.Guyton AC. Blood pressure control--special role of the kidneys and body fluids. Science. 1991;252(5014):1813–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2063193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamler J, Rose G, Elliott P, Dyer A, Marmot M, Kesteloot H, et al. Findings of the International Cooperative INTERSALT Study. Hypertension. 1991;17(1 Suppl):I9–15. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.1_suppl.i9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meneton P, Jeunemaitre X, de Wardener HE, MacGregor GA. Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(2):679–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddy FJ. Role of dietary salt in hypertension. Life Sci. 2006;79(17):1585–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoner W, Scheiner-Bobis G. Role of endogenous cardiotonic steroids in sodium homeostasis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(9):2723–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagrov AY, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61(1):9–38. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesher M, Dvela M, Igbokwe VU, Rosen H, Lichtstein D. Physiological roles of endogenous ouabain in normal rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(6):H2026–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00734.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Salt intake and depletion increase circulating levels of endogenous ouabain in normal men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290(3):R553–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00648.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedorova OV, Doris PA, Bagrov AY. Endogenous marinobufagenin-like factor in acute plasma volume expansion. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1998;20(5–6):581–91. doi: 10.3109/10641969809053236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd MA, Sandberg SM, Edwards BS. Role of renal Na+, K(+)-ATPase in the regulation of sodium excretion under normal conditions and in acute congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85(5):1912–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Wardener HE. Natriuretic hormone. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53(1):1–8. doi: 10.1042/cs0530001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddy FJ, Overbeck HW. The role of humoral agents in volume expanded hypertension. Life Sci. 1976;19(7):935–47. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaustein MP. Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation, and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am J Physiol. 1977;232(5):C165–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.232.5.C165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaustein MP, Zhang J, Chen L, Song H, Raina H, Kinsey SP, et al. The pump, the exchanger, and endogenous ouabain: signaling mechanisms that link salt retention to hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53(2):291–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.119974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dostanic-Larson I, Van Huysse JW, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The highly conserved cardiac glycoside binding site of Na, K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(44):15845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507358102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loreaux EL, Kaul B, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. Ouabain-Sensitive alpha1 Na, K-ATPase enhances natriuretic response to saline load. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(10):1947–54. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Yan Y, Liu L, Xie Z, Malhotra D, Joe B, et al. Impairment of Na/K-ATPase Signaling in Renal Proximal Tubule Contributes to Dahl Salt-sensitive Hypertension. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):22806–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.246249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Kesiry R, Periyasamy SM, Malhotra D, Xie Z, Shapiro JI. Ouabain induces endocytosis of plasmalemmal Na/K-ATPase in LLC-PK1 cells by a clathrin-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 2004;66(1):227–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai H, Wu L, Qu W, Malhotra D, Xie Z, Shapiro JI, Liu J. Regulation of Apical NHE3 Trafficking by Ouabain-Induced Activation of Basolateral Na/K-ATPase Receptor Complex. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294(2):C555–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00475.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Xie ZJ. The sodium pump and cardiotonic steroids-induced signal transduction protein kinases and calcium-signaling microdomain in regulation of transporter trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802(12):1237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oweis S, Wu L, Kiela PR, Zhao H, Malhotra D, Ghishan FK, et al. Cardiac glycoside downregulates NHE3 activity and expression in LLC-PK1 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(5):F997–1008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00322.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang M, Cai T, Tian J, Qu W, Xie ZJ. Functional Characterization of Src-interacting Na/K-ATPase Using RNA Interference Assay. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(28):19709–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haber RS, Pressley TA, Loeb JN, Ismail-Beigi F. Ionic dependence of active Na-K transport: “clamping” of cellular Na+ with monensin. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(1 Pt 2):F26–33. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.253.1.F26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haggerty JG, Agarwal N, Reilly RF, Adelberg EA, Slayman CW. Pharmacologically different Na/H antiporters on the apical and basolateral surfaces of cultured porcine kidney cells (LLC-PK1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(18):6797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soleimani M, Watts BA, 3rd, Singh G, Good DW. Effect of long-term hyperosmolality on the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE-3 in LLC-PK1 cells. Kidney Int. 1998;53(2):423–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klisic J, Zhang J, Nief V, Reyes L, Moe OW, Ambuhl PM. Albumin regulates the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in OKP cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(12):3008–16. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000098700.70804.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(2):121–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Algharably N, Owler D, Lamb JF. The rate of uptake of cardiac glycosides into human cultured cells and the effects of chloroquine on it. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35(20):3571–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90628-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonough AA, Biemesderfer D. Does membrane trafficking play a role in regulating the sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 in the proximal tubule? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2003;12(5):533–41. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang LE, Maunsbach AB, Leong PK, McDonough AA. Differential traffic of proximal tubule Na+ transporters during hypertension or PTH: NHE3 to base of microvilli vs. NaPi2 to endosomes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287(5):F896–906. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aperia A. Regulation of sodium/potassium ATPase activity: impact on salt balance and vascular contractility. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3(2):165–71. doi: 10.1007/s11906-001-0032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Liang M, Liu L, Malhotra D, Xie Z, Shapiro JI. Ouabain-induced endocytosis of the plasmalemmal Na/K-ATPase in LLC-PK1 cells requires caveolin-1. Kidney Int. 2005;67(5):1844–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lingrel JB, Kuntzweiler T. Na+, K(+)-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(31):19659–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanco G, Mercer RW. Isozymes of the Na-K-ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(5 Pt 2):F633–50. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.5.F633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweadner KJ. Isozymes of the Na+/K+-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;988(2):185–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aizman O, Uhlen P, Lal M, Brismar H, Aperia A. Ouabain, a steroid hormone that signals with slow calcium oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(23):13420–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221315298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Tian J, Haas M, Shapiro JI, Askari A, Xie Z. Ouabain interaction with cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase initiates signal cascades independent of changes in intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):27838–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aydemir-Koksoy A, Abramowitz J, Allen JC. Ouabain-induced signaling and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(49):46605–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas M, Wang H, Tian J, Xie Z. Src-mediated inter-receptor cross-talk between the Na+/K+-ATPase and the epidermal growth factor receptor relays the signal from ouabain to mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18694–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lingrel JB. The Physiological Significance of the Cardiotonic Steroid/Ouabain-Binding Site of the Na, K-ATPase. Annual Review of Physiology. 2010;72:395–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates NA, McDougall JG. Effects of direct renal arterial infusion of bufalin and ouabain in conscious sheep. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;108(3):627–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly MP, Quinn PA, Davies JE, Ng LL. Activity and Expression of Na+-H+ Exchanger Isoforms 1 and 3 in Kidney Proximal Tubules of Hypertensive Rats. Circ Res. 1997;80(6):853–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris RC, Brenner BM, Seifter JL. Sodium-hydrogen exchange and glucose transport in renal microvillus membrane vesicles from rats with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1986;77(3):724–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI112367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P, Miller ML, Soleimani M, Gawenis LR, et al. Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet. 1998;19(3):282–5. doi: 10.1038/969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorenz JN, Schultheis PJ, Traynor T, Shull GE, Schnermann J. Micropuncture analysis of single-nephron function in NHE3-deficient mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(3 Pt 2):F447–53. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.3.F447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonough AA. Mechanisms of proximal tubule sodium transport regulation that link extracellular fluid volume and blood pressure. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2010;298(4):R851–R61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00002.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Shapiro JI. Regulation of sodium pump endocytosis by cardiotonic steroids: Molecular mechanisms and physiological implications. Pathophysiology. 2007;14(3–4):171–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]