Abstract

Hexokinase (HXK; EC 2.7.1.1) regulates carbohydrate entry into glycolysis and is known to be a sensor for sugar-responsive gene expression. The effect of abiotic stresses on HXK activity was determined in seedlings of the flood-tolerant plant Echinochloa phyllopogon (Stev.) Koss and the flood-intolerant plant Echinochloa crus-pavonis (H.B.K.) Schult grown aerobically for 5 d before being subjected to anaerobic, chilling, heat, or salt stress. HXK activity was stimulated in shoots of E. phyllopogon only by anaerobic stress. HXK activity was only transiently elevated in E. crus-pavonis shoots during anaerobiosis. In roots of both species, anoxia and chilling stimulated HXK activity. Thus, HXK is not a general stress protein but is specifically induced by anoxia and chilling in E. phyllopogon and E. crus-pavonis. In both species HXK exhibited an optimum pH between 8.5 and 9.0, but the range was extended to pH 7.0 in air-grown E. phyllopogon to 6.5 in N2-grown E. phyllopogon. At physiologically relevant pHs (6.8 and 7.3, N2 and O2 conditions, respectively), N2-grown seedlings retained greater HXK activity at the lower pH. The pH response suggests that in N2-grown seedlings HXK can function in a more acidic environment and that a specific isozyme may be important for regulating glycolytic activity during anaerobic metabolism in E. phyllopogon.

HXKs (EC 2.7.1.1) are ubiquitous, constitutive enzymes found in all organisms and have been localized within the cytosol, mitochondria, and plastids of higher plants (Miernyk and Dennis, 1983; Schnarrenberger, 1990; Galina et al., 1995). The enzymes catalyze the phosphorylation of hexose sugars, typically Glc and Fru, that are produced during catabolism of Suc. Phosphorylation of hexoses by HXKs is essentially an irreversible metabolic step regulating the entry of Glc into glycolysis. Several studies have shown that plants typically contain an array of three to five HXKs that differ in their chromatographic and kinetic properties (Kruger, 1990). The native molecular masses of HXKs vary considerably, from 38 kD in castor oil seeds (Miernyk and Dennis, 1983) to 118 kD in potato tubers (Renz et al., 1993). Even within the same species the apparent native molecular masses of the HXKs are variable: 39 and 59 kD in maize kernels (Doehlert, 1989); 66, 102, 105, and 118 kD in potato tubers (Renz et al., 1993); and 50 and 100 kD in wheat germ (Higgins and Easterby, 1974). In those cases in which the subunit molecular masses have been determined (i.e. wheat germ [Higgins and Easterby, 1974], pea [Copeland et al., 1978], and mammals [Colowick, 1973]), HXKs are monomeric and the smaller isozymes do not appear to be subunits of the larger isoforms. Only in yeast has the native form of HXK been reported to be a dimer (Schmidt and Colowick, 1973).

The physiological significance of multiple forms of HXKs is not clear. Some HXKs are specific for Glc (i.e. GLKs) or Fru (i.e. FKs), although other forms can utilize either sugar as a substrate (Kruger, 1990). Part of the variation among HXK isozymes may reflect this specificity for a sugar substrate. HXKs generally utilize ATP as the nucleoside substrate, and Suc metabolism proceeds through the action of invertase and HXKs. However, some FKs utilize UTP as the phosphoryl donor (Huber and Akazawa, 1986; Baysdorfer et al., 1989; Xu et al., 1989; Schnarrenberger, 1990). Mobilization of Suc occurs through the concerted action of Susy, UDP-Glc pyrophosphorylase, and FK via a uridine-nucleotide- and PPi-dependent pathway (Huber and Akazawa, 1986; Xu et al., 1989). Thus, the relative abundance of FKs and GLKs correlates with the pathway of Suc catabolism that operates in a particular tissue.

Although control of glycolytic flux is usually shared among all enzymes of the pathway (Kaczer and Burns, 1973; Rapoport et al., 1974), stress conditions may permit certain enzymes to exert a greater proportion of control. HXKs are reported to regulate glycolytic flux in human erythrocytes (Rapoport et al., 1974), perfused rat hearts (Kashiway et al., 1994), and pancreatic islet beta cells (German, 1993) during anaerobic stress, and in the red blood cells of rabbits during exposure to oxygen-free radicals (Stocchi et al., 1994). In potato tubers HXKs are subject to product inhibition by ADP, leading to the proposal that HXKs control glycolytic flux during anoxia in higher plants (Renz and Stitt, 1993). Under conditions that decrease the ATP-to-ADP ratio, such as anaerobic stress, ADP would inhibit HXK activity. Presumably, the reduction in HXK activity prevents depletion of cytosolic Pi so that sufficient Pi is present for ATP synthesis.

In maize root tips (Bouny and Saglio, 1996) and tomato roots (Germain et al., 1997), HXK activity is stimulated by hypoxia but does not increase during anoxia, whether or not the root tips are hypoxically pretreated to enhance their survival. Native-PAGE activity gels revealed one HXK, one GLK, and two FK isozymes in maize. No new isoforms were detected, although the resolution obtained with this technique is insufficient to definitively exclude this possibility. The low HXK activity, however, accounts for most of the reduction in glycolytic flux in anaerobically treated maize root tips, and both HXK induction and glycolytic flux recover when the stress is removed, suggesting that HXK regulates glycolytic activity (Bouny and Saglio, 1996).

In the present study we examined HXK activity in response to several abiotic stresses, characterized its enzymatic activity under anaerobic conditions, and determined the influence of pH on its activity in two barnyard grass species of Echinochloa. The Echinochloa genus, with several flood-tolerant and -intolerant species, has been well characterized with regard to its metabolic adaptations to anoxia and is an excellent model system to investigate differences in the environmental regulation of gene expression and metabolism. The tolerant species Echinochloa phyllopogon has been extensively characterized because of its ability to germinate and grow under anoxia, whereas the intolerant species Echinochloa crus-pavonis has been studied for its inability to germinate under anoxia (Kennedy et al., 1992). In E. phyllopogon, anaerobic germination and growth occur solely by emergence and elongation of the coleoptile; the radicle does not emerge from the seed in the absence of O2 (VanderZee and Kennedy, 1981). Unlike the flood-intolerant species, E. phyllopogon maintains an active carbohydrate and lipid metabolism high ATP levels, and energy charge during long exposures to anaerobic conditions (Kennedy et al., 1987, 1992; Fox et al., 1988). This coordinated metabolic activity by the tolerant species is a product of both differential gene expression and posttranslational regulation of metabolic activity during anoxia. HXK is postulated to serve a dual role in this regard by regulating entry of Glc into glycolysis and as part of the mechanism regulating the expression of sugar-responsive genes (Koch, 1996; Lang et al., 1997).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Seeds of Echinochloa phyllopogon (Stev.) Koss or Echinochloa crus-pavonis (H.B.K.) Schult were surface-sterilized with 50% (v/v) bleach solutions, vacuum infiltrated with deionized water for 10 min, and placed in Petri plates lined with germination paper wetted with 10 mL of sterile deionized water. The seeds were germinated at 28°C for up to 7 d in the dark in an aerobic incubator (Fisher Scientific) or in an anaerobic chamber (Forma Scientific) continuously flushed with a 90% (v/v) N2/10% (v/v) H2 gas mixture. Five-day-old aerobically grown seedlings were subjected to one of following abiotic stresses: (a) transferred into the anaerobic chamber for 2 d (anaerobic stress), (b) subjected to 4°C for 6 h (chilling stress), (c) incubated at 43°C for 6 h (heat stress), or (d) supplied with 400 mm NaCl throughout the germination period (salt stress). Following the various treatments, the seedlings were frozen in liquid N2. Shoots, roots, and seeds (i.e. the remnant of the seed still integrally attached to the seedling) were harvested and ground to a fine powder under liquid N2 with a mortar and pestle and stored at −80°C until used.

HXK Assay

Crude extracts were prepared by grinding 250 to 300 mg of powdered tissue with extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl [pH 8.75], 1 mm MgCl2, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 100 μm leupeptin, 100 μm PMSF, 1 mm n-tosyl-l-phenylalaninechloromethylketone, and 0.05% [v/v] β-mercaptoethanol) in a 1:1 (w/v) ratio, and the extract was clarified by microcentrifugation at 13,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was dialyzed against buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.75), 1 mm MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol for 60 min with two changes of buffer. HXK activity in the extract was assayed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm at 30°C in a 1-mL reaction volume containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.75), 10 mm MgCl2, 110 mm Glc, 200 μm NAD+, 500 μm ATP, 2 units of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.49), and 33 μL of crude extract (50–100 μg of protein). Protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Bradford (1976) using the Bio-Rad protein stain with BSA as the standard.

RESULTS

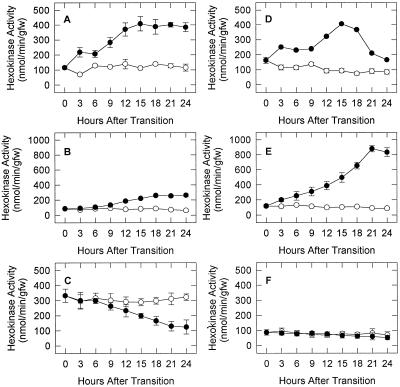

Anaerobic stress stimulated HXK activity in both shoots (Fig. 1A) and roots (Fig. 1B) of the flood-tolerant species E. phyllopogon, whereas chilling stress elevated HXK activity only in roots. Heat shock and salt stress inhibited HXK in both shoots and roots. In contrast, in the flood-intolerant species E. crus-pavonis, shoot HXK activity was unaffected or inhibited by the four stresses (Fig. 1D), but in roots it was stimulated to varying degrees by each of the stresses (Fig. 1E). In seeds of both species (Fig. 1, C and F), abiotic stresses generally inhibited HXK activity, except for chilling stress in E. crus-pavonis, which did not affect its activity.

Figure 1.

Relative hexokinase (HK) activity in shoots (A and D), roots (B and E), and seeds (C and F) of E. phyllopogon (A–C) and E. crus-pavonis (D–F) in response to abiotic stresses. Seedlings were grown aerobically for 5 d and harvested immediately (Control 1), continued in air for 2 d (Control 2), or subjected to the indicated stresses. Activities are expressed relative to Control 1. Absolute activities of the Control 1 plants were 217, 87, and 332 nmol min−1 g−1 fresh weight for shoots, roots, and seeds, respectively, of E. phyllopogon, and 106, 21, and 88 nmol min−1 g−1 fresh weight for shoots, roots, and seeds, respectively, of E. crus-pavonis. Values are means ± sd of three replicates.

The anaerobic stimulation of HXK activity in shoots of E. phyllopogon occurred within 3 h and to a higher level (4-fold) than in roots, in which the response was apparent only after 9 h and was ultimately stimulated only 2.5-fold after 24 h of anoxia (Fig. 2, A and B). In seeds (Fig. 2C), inhibition of HXK activity occurred after 9 h of anoxia and continued for the duration of the experiment.

Figure 2.

HXK activity in shoots (A and D), roots (B and E), and seeds (C and F) of E. phyllopogon (A–C) and E. crus-pavonis (D–F) during anaerobic stress. Seedlings were grown for 5 d in air and HXK activities were determined during the subsequent 24-h period in seedlings that were maintained in air (○) or transferred into an anaerobic chamber (•). Values are means ± sd of three replicates. gfw, Grams fresh weight.

Shoots of E. crus-pavonis exhibited a 2-fold stimulation of HXK activity by 18 h of anoxia, but activity declined to nearly initial levels after 24 h in N2 (Fig. 2D). In roots, however, HXK activity was elevated within 3 h and the activity was stimulated 8-fold by 18 h in N2 (Fig. 2E). Anoxia did not affect HXK activity in seeds (Fig. 2F). The comparatively low and transient nature of HXK activity in the shoots may be one factor that limits the ability of E. crus-pavonis to withstand flooding in contrast to E. phyllopogon.

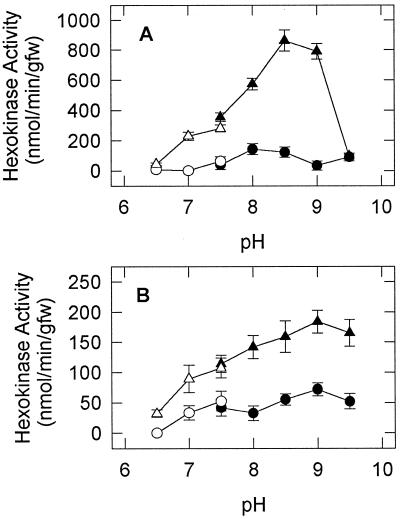

Having identified that HXK activity was stimulated to a larger extent in shoots of E. phyllopogon and roots of E. crus-pavonis, we proceeded to characterize the enzyme in these respective organs. To assess how changes in cytoplasmic pH affect HXK activity, crude extracts from shoots of E. phyllopogon and roots of E. crus-pavonis (grown in air or transferred to N2 for 2 d) were assayed for activity at several pHs (Fig. 3). In E. phyllopogon HXK from shoots of aerobically grown seedlings exhibited a broad pH optima peak between 8.0 and 8.5, whereas those subjected to anoxia exhibited significantly higher activities, with a sharp pH optimum at approximately 8.75 and a distinct shoulder below 7.5 (Fig. 3A). HXK from both aerobically and anaerobically grown roots of E. crus-pavonis, however, exhibited a broad curve, “peaking” at pH 9.0 with only a slight shoulder below 7.5 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

HXK activity as a function of pH in E. phyllopogon (A) and E. crus-pavonis (B). Crude protein extracts were prepared from shoots of E. phyllopogon and roots of E. crus-pavonis grown in air (○, •) or transferred to N2 for 2 d (▵, ▴) and assayed for HXK activity at the indicated pH using Hepes-KOH (○, ▵) or Tris-HCl (•, ▴) buffer systems. Values are means ± sd of three replicates. gfw, Grams fresh weight.

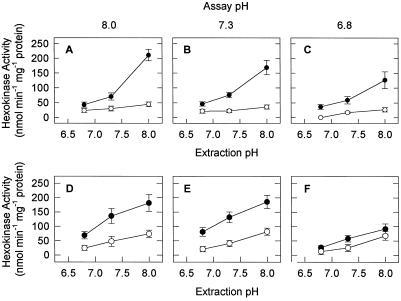

In vivo measurements of cytoplasmic pH in maize root tips have demonstrated that the pH rapidly declines from approximately 7.4 in air to approximately 6.8 under hypoxic conditions (Roberts et al., 1984). Although differences in HXK activity between aerobically and anaerobically grown seedlings as a function of pH were more pronounced at higher pHs (Fig. 3), we more closely examined the effect of pH on HXK activity within a physiologically relevant range for the two species of Echinochloa. In addition to extracting and assaying HXK near its pH optimum (8.0), the enzyme was extracted from shoots of E. phyllopogon and its activity was determined at pH 7.3 and 6.8 to assess its activity at the approximate pH of the cytoplasm during aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively (Fig. 4, A–C). At a pH of less than optimum (i.e. <8.75), HXK activity was significantly reduced.

Figure 4.

HXK activity in shoots of E. phyllopogon (A–C) and E. crus-pavonis (D–F) as a function of extraction and assay buffer pH. Five-day-old seedlings grown aerobically (○) or anaerobically (•) were extracted at pH 8.0, 7.3, or 6.8 and assayed at pH 8.0 (A and D), 7.3 (B and E), or 6.8 (C and F). The pH values were selected for being near optimum for HXK activity and for physiological relevance. Values are means ± sd of three replicates.

It is interesting that the slopes of the activity- versus extraction-pH curves of shoots from anaerobically grown seedlings (143, 104, and 76 at assay pH 8.0, 7.3, and 6.8, respectively), were 3- to 8-fold greater than the corresponding slopes of aerobically grown seedlings (18, 12, and 22 at assay pH 8.0, 7.3, and 6.8, respectively; Fig. 4, A–C). The different responses of HXK activity- versus extraction-pH curves in shoots of aerobically and anaerobically grown seedlings demonstrate that HXK activity in shoots of anaerobically grown seedlings of E. phyllopogon was more responsive to subtle changes in pH than in those grown in air, suggesting that different isozymes may predominate under these two growth conditions. In similar experiments with roots of 5-d-old seedlings of E. crus-pavonis, the slopes of the activity- versus extraction-pH curves in roots of anaerobically grown seedlings (92, 87 and 52 at assay pH 8.0, 7.3, and 6.8, respectively) were less than 2-fold greater than the corresponding slopes of aerobically grown seedlings (41, 51, and 42, respectively; Fig. 4, D–F).

DISCUSSION

Stimulation of HXK Activity by Abiotic Stress

Elevation of HXK activity is not a general stress response in Echinochloa species. HXK activity was specifically stimulated by anaerobic and chilling stresses, and its expression exhibited organ specificity. HXK activity was elevated in roots of both E. phyllopogon and E. crus-pavonis when subjected to anoxia or 4°C. In shoots, however, HXK activity was induced only in E. phyllopogon and only in response to anaerobic conditions. The different patterns of induction of HXK activity in shoots of the flood-tolerant and -intolerant species were correlated with their different abilities to germinate and grow anaerobically. Under anaerobic conditions, E. phyllopogon germinates and growth occurs solely via shoot elongation; the radicle fails to emerge from the seed unless O2 is present (VanderZee and Kennedy, 1981). In contrast, E. crus-pavonis fails to germinate in an anaerobic environment and HXK activity is not induced. Similarly, HXK and FK activities are inhibited in roots of maize (Bouny and Saglio, 1996) and tomato (Germain et al., 1997) during anaerobiosis. However, if E. crus-pavonis seeds are given an aerobic treatment prior to transfer into anaerobic conditions, the seeds germinate, growth of both the shoot and root occurs (Zhang et al., 1994), and HXK activity is at least transiently induced (Fig. 2). Thus, the ability of Echinochloa spp. to germinate and grow under anoxic conditions correlates with stimulation of HXK activity in an organ-specific manner. Increased levels of HXK activity are postulated to increase the entry of hexoses into glycolysis to sustain anaerobic ATP production in E. phyllopogon.

In maize, however, inhibition of HXK activity, low levels of hexose phosphates (Bouny and Saglio, 1996), and induction of Susy by anoxia (Talercio and Chourey, 1989) led to the conclusion that metabolism of Suc occurs predominately via the Susy pathway. Experiments with a Susy double mutant confirmed that aerobic growth is not dependent on Susy activity but is required for anaerobic growth in maize (Ricard et al., 1998). Induction of Susy by low O2 conditions in tomato (Germain et al., 1997, wheat (Marana et al., 1990), and rice (Ricard et al., 1991) suggests that anaerobic metabolism of Suc via Susy is a general plant response. In the present study it is reasonable to infer from the transient induction of HXK activity (Fig. 2) that E. crus-pavonis responds to anoxia in a manner analogous to maize. In contrast, E. phyllopogon appears to retain the hexose-phosphorylating pathway; HXK activity is strongly induced (Fig. 2) and increased incorporation of 14C into sugar-monophosphates from Suc occurs during anoxia (Rumpho and Kennedy, 1983).

The appearance and abundance of specific HXKs have been found to depend on the organ and developmental state of the tissue in potato. FK3 is present in leaves, whereas FK1 and FK2 are the major forms in growing tubers (Renz et al., 1993). The high levels of FKs in tubers correspond with Suc utilization via Susy and UDP-Glc pyrophosphorylase. In stored tubers elevated levels of HXK1 and HXK2 activities (Renz et al., 1993) correspond to a decline in Suc utilization via Susy (Geigenberger and Stitt, 1993) and elevation of invertase levels (Richardson et al., 1990). In sprouting tubers HXK1 is the predominant form of HXK, possibly because starch is the major carbohydrate source (Renz et al., 1993). Thus, changes in the specific forms of FKs and GLKs appear to regulate carbon flow through Fru and Glc pools at different stages of development.

Localization of HXKs may be important for directing Glc to specific subcellular compartments at critical times during development to supply carbon skeletons for various anabolic pathways. For instance, high levels of HXK activity in plastids of castor oil seed endosperm may be necessary to provide substrates for fatty acid biosynthesis (Miernyk and Dennis, 1983). HXKs have been reported on the outer membranes of mitochondria of spinach leaves (Baldus et al., 1981) and avocado (Copeland and Tanner, 1988), the outer membranes of spinach leaf chloroplasts (Stitt et al., 1978), in spinach chloroplasts (Schnarrenberger, 1990), and in the plastids and mitochondria of castor oil seed endosperm (Miernyk and Dennis, 1983).

HXK-Regulated Gene Expression

HXK is known to act as the sensor for Glc-mediated gene expression in yeast (Entian, 1980; Entian and Frohlich, 1984). The mechanism for gene regulation by HXK is not well defined, but a catalytically induced conformational change is required (Ma and Botstein, 1986; Ma et al., 1989; Rose et al., 1991). Additional factors such as a Glc transporter, an effector protein, and protein kinases are suggested to interact with HXKs in sensing the Glc status of the cell and altering gene expression (Thevelein, 1991). Using transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing sense and anti-sense HXK gene constructs, Jang et al. (1997) demonstrated that HXK is a sensor for a number of sugar responses in higher plants as well. HXK signaling is involved in the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation and chlorophyll accumulation in response to increasing concentrations of Glc in the medium, and is also responsible for the repression of the chlorophyll a/b-binding protein (cab1) and ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit (rbcs) and activation of nitrate reductase (nr1) gene expression. Furthermore, in Arabidopsis seedlings expressing the yeast HXK2 gene (the gene responsible for sugar sensing in yeast), the sugar-sensing function can be uncoupled from its catalytic activity.

HXK has also been shown to repress the expression of mannitol dehydrogenase in celery cell-suspension cultures (Prata et al., 1997) and α-amylase rice embryos (Yamaguchi et al., 1997) when sugars were present in the culture media. In both cases, the repression of gene expression was relieved during sugar starvation. The use of mannoheptulose, a competitive inhibitor of HXK, and 2-deoxyglucose, a sugar analog that is phosphorylated by HXK but not metabolized further, mimics the effects of sugar starvation, indicating that HXK regulates the expression of these two genes.

An analogous mechanism may be important for signaling anaerobic stress and regulating the associated changes in gene expression in Echinochloa spp. In addition to changes in sugar status and metabolic flux (Fox et al., 1994), anaerobiosis influences the overall adenylate energy charge of the seedlings and the synthesis of adenylates (Kennedy et al., 1987). Since ATP is a substrate for HXK, fluctuations in ATP-to-ADP ratios would also be expected to modulate HXK activity. Renz and Stitt (1993) have shown that ATP-to-ADP ratios regulate HXK activity in potato. Under anaerobic conditions availability of ATP may be an additional determinant of HXK activity and its associated feedback on gene expression.

Cytoplasmic acidification is an early consequence of anaerobiosis and has pleiotropic effects on cellular metabolism (Roberts et al., 1984). One effect is to modulate HXK activity. Results of in vitro experiments with crude extracts suggest that shoots of anaerobically grown E. phyllopogon seedlings retain partial HXK activity at pH 6.8 but aerobically grown seedlings do not (Fig. 3). An HXK with an acidic pH optimum would maintain carbohydrate entry into glycolysis, fatty acid biosynthesis, and other metabolic pathways during anaerobiosis. Since the rate of hexose phosphorylation is more important than the concentration of hexose phosphates in signaling the sugar status of the cell to the nucleus, the combined effects of sugar supply, ATP concentration, and cytoplasmic pH in modulating HXK activity may permit one HXK isozyme in Echinochloa spp. to serve as a sensor of the aeration state of the cell.

Whereas several HXK genes have been cloned from yeast and animals, only two HXKs have been cloned and characterized in plants. Smith et al. (1993) cloned an FK gene from potato and found the sequence homology to yeast and animal HXKs to be low. A HXK has also been cloned from an Arabidopsis cDNA library by functional complementation of a yeast triple mutant (Dai et al., 1995). This gene encodes a 47-kD protein that preferentially utilizes Glc over Fru. Jang and Sheen (1994) cloned and are characterizing two additional plant HXK genes. Isolation and characterization of additional HXK genes in plants will be important for analyzing the expression of specific isozymes and their significance during Glc metabolism in relation to environmental stress and regulation of homeostasis in plant cells. Studies in yeast indicate that GLKs do not have the same sugar-sensing capabilities as HXKs (Rose et al., 1991). Variability among HXKs, GLKs, and FKs in plants may be one level of complexity in regulating expression of sugar-responsive genes.

Conclusion

In Echinochloa spp. HXK is not a general stress protein but is specifically induced by anoxia and chilling in an organ-dependent manner. Furthermore, the two Echinochloa spp. exhibit different patterns of HXK activity that correlate with their ability to withstand flooding. The flood-intolerant E. crus-pavonis exhibits a weak, transient elevation of HXK activity in shoots during anaerobiosis, whereas a strong, persistent stimulation occurs in the shoots of the flood-tolerant species. The decline in HXK activity in E. crus-pavonis is consistent with results from other species (e.g. maize, tomato, wheat, and rice), in which metabolism of Suc occurs primarily via Susy rather than by invertase under low-O2 conditions. In contrast, E. phyllopogon increases its capacity to phosphorylate hexoses arising from Suc hydrolysis via invertase. The invertase-HXK pathway for Suc catabolism is not an absolute requirement for flood tolerance, however, because rice induces the Susy pathway under anoxia. Instead, E. phyllopogon has adopted an alternative strategy for metabolizing carbohydrates during anaerobic stress. The occurrence of this adaptation in other species and the expression of HXK at the isozyme and molecular levels need to be explored further in the context of improving flood tolerance in commercially important crop plants.

Abbreviations:

- FK

fructokinase

- GLK

glucokinase

- HXK

hexokinase

- Susy

Suc synthase

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (no. 94-37100-0310) and the USDA-Cooperative State Research Service Triagency Plant Biology Program on Collaborative Research (no. 92-37105-7675).

LITERATURE CITED

- Baldus B, Kelly GJ, Latzko E. Hexokinases in spinach leaves. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:1811–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Baysdorfer C, Kremer DF, Sicher RC. Partial purification and characterization of fructokinase activity from barley leaves. J Plant Physiol. 1989;134:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bouny JM, Saglio PH. Glycolytic flux and hexokinase activities in anoxic maize root tips acclimated by hypoxic pretreatment. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:187–194. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye-binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colowick SP (1973) The hexokinases. In PD Boyer, ed, The Enzymes, Vol 9. Academic Press, New York, pp 1–48

- Copeland L, Harrison DD, Turner JF. Fructokinase (fraction III) of pea seeds. Plant Physiol. 1978;62:291–294. doi: 10.1104/pp.62.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland L, Tanner GJ. Hexose kinases of avocado. Plant Physiol. 1988;74:531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Dai N, Schaffer AA, Petreikov M, Granot D. Arabidopsis thaliana hexokinase cDNA isolated by complementation of yeast cells. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:879–880. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehlert DC. Separation and characterization of four hexose kinases from developing maize kernels. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:1042–1048. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.4.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entian K-D. Genetic and biochemical evidence for hexokinase PII as a key enzyme involved in carbon catabolite repression in yeast. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;178:633–637. doi: 10.1007/BF00337871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entian K-D, Frohlich K-U. Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants provide evidence for hexokinase PII as a bifunctional enzyme with catalytic and regulatory domains for triggering carbon catabolite repression. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:29–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.29-35.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox TC, Kennedy RA, Alani AA (1988) Biochemical adaptations to anoxia in barnyard grass. In DD Hook, ed, The Ecology and Management of Wetlands, Vol 1. Croom-Helm Publishers, London, pp 359–372

- Fox TC, Kennedy RA, Rumpho ME. Energetics of plant growth under anoxia: metabolic adaptations of Oryza sativa and Echinochloa phyllopogon. Ann Bot. 1994;74:445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Galina A, Reis M, Albuquerque MC, Puyou AG, Puyou MTG, de Meis L. Different properties of the mitochondrial and cytosolic hexokinases in maize roots. Biochem J. 1995;309:105–112. doi: 10.1042/bj3090105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P, Stitt M. Sucrose synthase catalyzes a readily reversible reaction in potato tubers and other plant tissues. Planta. 1993;189:329–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00194429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain V, Ricard B, Raymond P, Saglio P. The role of sugars, hexokinase, and sucrose synthase in the determination of hypoxically induced tolerance to anoxia in tomato roots. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:167–175. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German MS. Glucose sensing in pancreatic islet beta cells: the key role of glucokinase and the glycolytic intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1781–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins TJC, Easterby JS. Wheat germ hexokinase: physical and active-site properties. Eur J Biochem. 1974;45:147–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber SC, Akazawa T. A novel sucrose synthase pathway for sucrose degradation in cultured sycamore cells. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:1008–1013. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.4.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J-C, León P, Zhou L, Sheen J. Hexokinase as a sugar sensor in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1997;9:5–19. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J-C, Sheen J. Sugar sensing in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1665–1679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczer H, Burns JA. The control of flux. Symp Soc Exp Bot. 1973;28:65–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiway Y, Sato K, Tsuchiya N, Thomas S, Fell DA, Veech RL, Passonneau JV. Control of glucose utilization in working perfused rat heart. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25502–25514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RA, Rumpho ME, Fox TC (1987) Germination physiology of rice and rice weeds: metabolic adaptation to anoxia. In RMM Crawford, ed, Plant Life in Aquatic and Amphibious Habitats. Blackwell Press, Oxford, UK, pp 193–203

- Kennedy RA, Rumpho ME, Fox TC. Anaerobic metabolism in plants. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:1–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KE. Carbohydrate-modulated gene expression in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:509–540. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger NJ (1990) Carbohydrate synthesis and degradation. In DT Dennis, DM Turpin, eds, Plant Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Longman and Harlow, New York, pp 59–76

- Ma H, Bloom LM, Walsh CT, Botstein D. The residual enzymatic phosphorylation activity of hexokinase II mutants is correlated with glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5643–5649. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Botstein D. Effects of null mutations in the hexokinase genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on catabolite repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4046–4052. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marana C, Garcia-Olmedo F, Carbonero P. Differential expression of two types of sucrose synthase-encoding genes in wheat in response to anaerobiosis, cold shock and light. Gene. 1990;88:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90028-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miernyk JA, Dennis DT. Mitochondrial, plastid, and cytosolic isozymes of hexokinase from developing endosperm of Ricinus communis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;226:458–468. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prata RTN, Williamson JD, Conkling MA, Pharr DM. Sugar repression of mannitol dehydrogenase activity in celery cells. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:307–314. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport TA, Heinrich R, Jacobasch G, Rapoport S. A linear steady-state treatment of enzymatic chains. A mathematical model of glycolysis of human erythrocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1974;42:107–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz A, Merlo L, Stitt M. Partial purification from potato tubers of three fructokinases and three hexokinases which show differing organ and developmental specificity. Planta. 1993;190:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Renz A, Stitt M. Substrate specificity and product inhibition of different forms of fructokinases and hexokinases in developing potato tubers. Planta. 1993;190:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ricard B, Rivoal J, Spiteri A, Pradet A. Anaerobic stress induces the transcription and translation of sucrose synthase in rice. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:669–674. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.3.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard B, VanToai T, Chourey P, Saglio P. Evidence for the critical role of sucrose synthase for anoxic tolerance of maize roots using a double mutant. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1323–1331. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.4.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DL, Davies HV, Ross HA, MacKay GR. Invertase activity and its relation to hexose accumulation in potato tubers. J Exp Bot. 1990;41:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JKM, Callis J, Wemmer D, Walbot V, Jardetsky O. Mechanism of cytoplasmic pH regulation in hypoxic maize root tips and its role in survival under hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3379–3383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Albig W, Entian K-D. Glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is directly associated with hexose phosphorylation by hexokinase PI and PII. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:511–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpho ME, Kennedy RA. Anaerobiosis in Echinochloa crus-galli (barnyard grass) seedlings. Intermediary metabolism and ethanol tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1983;72:44–49. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JJ, Colowick SP. Chemistry and subunit structure of yeast hexokinase isozymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1973;158:458–470. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnarrenberger C. Characterization and compartmentation, in green leaves, of hexokinases with different specificities for glucose, fructose, and mannose and for nucleoside triphosphates. Planta. 1990;181:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02411547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Taylor MA, Burch LR, Davies HV. Primary structure and characterization of a cDNA clone of fructokinase from potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv Record) Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1043. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Bulpin PV, ap Rees T. Pathway of starch breakdown in photosynthetic tissues of Pisum sativum. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1978;544:200–214. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocchi V, Biagiarelli B, Fiorani M, Palma F, Piccoli G, Cucchiarini L, Dacha M. Inactivation of rabbit red blood cell hexokinase activity promoted in vitro by an oxygen-radical-generating system. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:160–167. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talercio EW, Chourey PS. Post-transcriptional control of sucrose synthase expression in anaerobic seedlings of maize. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1359–1364. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein JM. Fermentable sugars and intracellular acidification as specific activators of the RAS-adenylate cyclase signaling pathway in yeast: the relationship to nutrient-induced cell cycle control. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1301–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderZee D, Kennedy RA. Germination and seedling growth in Echinochloa crus-galli var. oryzicola under anoxic conditions: structural aspects. Am J Bot. 1981;68:1269. -1277. [Google Scholar]

- Xu D-P, Sung S-JS, Loboda T, Lormanik PP, Black CC. Physiol. 1989;90:635–642. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.2.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi J, Umemura T, Futsuhara Y, Perata P. Sugar sensing and alpha-amylase gene repression in rice embryos (abstract no. 143) Plant Physiol. 1997;114:S-46. doi: 10.1007/s004250050275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Lin J-J, Mujer CV, Rumpho ME, Kennedy RA. Effect of aerobic priming on the response of Echinochloa crus-pavonis to anaerobic stress. Protein synthesis and phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:1149–1157. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]