Abstract

Cell- and receptor-specific regulation of cell migration by Gi/oα-proteins remains unknown in prostate cancer cells. In the present study, oxytocin (OXT) receptor (OXTR) was detected at the protein level in total cell lysates from C81 (an androgen-independent subline of LNCaP), DU145 and PC3 prostate cancer cells, but not in immortalized normal prostate luminal epithelial cells (RWPE1), and OXT induced migration of PC3 cells. This effect of OXT has been shown to be mediated by Gi/oα-dependent signaling. Accordingly, OXT inhibited forskolin-induced luciferase activity in PC3 cells that were transfected with a luciferase reporter for cAMP activity. Although mRNAs for all three Giα isoforms were present in PC3 cells, Giα2 was the most abundant isoform that was detected at the protein level. Pertussis toxin (PTx) inhibited the OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells. Ectopic expression of the PTx-resistant Giα2-C352G, but not wild type Giα2, abolished this effect of PTx on OXT-induced cell migration. The Giα2-targeting siRNA was shown to specifically reduce Giα2 mRNA and protein in prostate cancer cells. The Giα2-targeting siRNA eliminated OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells. These data suggest that Giα2 plays an important role in the effects of OXT on PC3 cell migration. The Giα2-targeting siRNA also inhibited EGF-induced migration of PC3 and DU145 cells. Expression of the siRNA-resistant Giα2, but not wild type Giα2, restored the effects of EGF in PC3 cells transfected with the Giα2-targeting siRNA. In conclusion, Giα2 plays an essential role in OXT and EGF signaling to induce prostate cancer cell migration.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor, Oxytocin receptor, G-protein, Prostate cancer, Cell migration

Introduction

Heterotrimeric guanosine phosphate-binding proteins (G-proteins) are composed of α, β, and γ subunits. Gβ and Gγ form a dimer that is associated with inactive Gα (1–3). Activated G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) catalyzes the exchange of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) for guanosine triphosphate (GTP) on Gα, resulting in the dissociation of Gβγ from the activated Gα (4). Gα subunits have intrinsic GTPase activities that hydrolyze the GTP into GDP and terminate the G-protein coupled signaling (4). The GTP hydrolysis is accelerated by the regulator of G-protein signaling protein (RGS) (4). There are 23 Gα isoforms that are divided into four subfamilies, including Gs, Gi/o, Gq/11, and G12/13 (4). Activation of Gi/o-proteins inhibits adenylyl cyclases and reduces intracellular cAMP levels (5). Giα1, Giα2, Giα3, GoαA, and GoαB are Gi/oα-proteins that are ubiquitously expressed and sensitive to pertussis toxin (PTx) (4). GoαA and GoαB are derived from splice variants of the Goα gene that is preferentially expressed in the central nervous system (6, 7). PTx catalyzes ADP ribosylation of the cystine (C) residues at C-terminal ends of the Gi/oα-proteins, which results in the uncoupling of these G-proteins from their cognate GPCRs (8). Substitution of the cystine for glycine eliminates the PTx ADP-ribosylation site, however, the resulting Gi/oα mutants have been shown to retain abilities to couple to GPCRs and induce biological responses (9).

Prostate cancer development and progression is androgen dependent, and androgen deprivation therapy is currently among the regular procedures to treat metastatic prostate cancer (10–12). However, disease relapse often ensues from androgen ablation, producing castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) that results in increased malignancy and poor prognosis (10, 12, 13). Emerging evidence has suggested that GPCR signaling plays an important role in prostate cancer progression (14). Activation of G12/13-proteins has been shown to increase prostate cancer invasion via activation of RhoA family of small G-proteins (15). Both Gs- and Gq-dependent signaling induce the transactivation of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells (16, 17), which has been shown to facilitate transition of primary prostate tumor cells to the androgen independent stage (18). Expression of RGS2, a negative regulator of Gi- as well as Gq-dependent signaling, is significantly reduced in human prostate cancer specimens when compared with the adjacent normal or hyperplastic prostate tissues (19). Therefore, signaling of GPCRs, either Gi- or Gq-coupled, is potentially amplified in primary prostate tumors. PTx has been shown to inhibit the growth of PC3 prostate cancer cells (20). PTx sensitivity indicates the involvement of Gi/o-dependent signaling (8). Nevertheless, PTx treatment cannot distinguish receptor- and cell-specific functions of Gi/oα isoforms. Activated CXCR3 receptor induces migration of T lymphocytes via a Giα2-dependent mechanism, which is counteracted by Giα3 (21). There is no evidence suggesting the presence of isoform-specific functions of heterotrimeric G-proteins in prostate cancer cells.

Oxytocin (OXT) is a peptide hormone that regulates normal prostate functions. OXT treatment has been shown to increase epithelial cell growth, 5α-reductase activity, and contractility in normal prostate (22–24). However, the information is very limited about the effect of OXT on prostate cancer progression. OXT receptor (OXTR) has been detected in tissues from hyperplastic and neoplastic prostate (25), but not in the epithelium of normal human prostate (26). Recently, OXTR has been shown to be the primary target of OXT in androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines (DU145 and PC3) (27). OXTR is a GPCR that promiscuously couples to multiple G-proteins including Gq and Gi (28, 29). Activated OXTR induces migration of PC3 cells via a PTx-sensitive mechanism (27). In the present study, OXTR protein was detected in prostate cancer cell lines (C81, DU145, and PC3), but not in the normal prostate epithelial cell line (RWPE1). Furthermore, we investigated whether specific Gi/oα isoforms were required for the migration of PC3 cells. Giα2 was the most abundant isoform of the Gi/oα family members that was detected at the protein level and this isoform was found to play an essential role in prostate cancer cell migration.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human OXT, pertussis toxin, bovine serum albumin (BSA), rabbit anti-OXTR antibody, anti-α-tubulin antibody, and mouse anti-β-actin antibody were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Mouse monoclonal anti-Giα1 antibody, rabbit anti-Giα2, and anti-Giα3 antibodies were obtained from EMD-Millipore (Temecula, CA)Total lysates from E. coli expressing recombinant rat Giα1, Giα2, and Giα3 proteins and an additional rabbit anti-human Giα2 antibody, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Steady glow luciferase reagent, M-MLV reverse transcriptase, T4-ligase, GoTaq qPCR master mix, and oligo dT primer were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Taq polymerase was purchased from Lucigen (Middleton, WI). Phusion high-fidelity PCR kit and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). DNA primers were purchased from IDT (San Jose, CA). EGF, Trizol, lipofectamine 2000, control and Giα2-targeting (siRNA ID#: s5875, Ambion) siRNAs were purchased from Life Technology (Grand Island, NY). TransIt-TKO transfection reagent was obtained from Mirus (Madison, WI). Rat tail collagen and transwell inserts were obtained from BD Biosciences (Irvine, CA). Cell culture reagents and G418 sulfate were purchased from Mediatech Inc (Manassas, VA).

Plasmids

Human Giα2 and the Giα2-C352G mutant in pcDNA3.1 (Life Technology) were obtained from Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). The siRNA-resistant Giα2 gene was created by modification of the Giα2 siRNA-targeting sequence without any change in the protein sequence. The modified sequence was generated by PCR and ligated into the Giα2 gene after digestion with Kpn I and BamH I restriction enzymes. Sequences of the two sets of PCR primers were, Forward 1: GCT TGG TAC CAC CAT GGG CTG; Reverse 1: GTG TTC GAA TAC ACT ACG GCT CGG TAC TGC CGG CAT TCC TCC TC, Forward 2: TAC CGA GCC GTA GTG TAT TCG AAC ACC ATC CAG TCC ATC ATG GC; Reverse 2: GCA GTG GAT CCA CTT CTT CCG CT. The siRNA-resistant Giα2 clone was verified by DNA sequencing. The pADneo2 C6-BGL plasmid containing luciferase reporter for cAMP was a gift from Dr. Tu-Yi (Creighton University, Omaha, NE).

Cell culture

Immortalized prostate luminal epithelial cell line (RWPE1), DU145 and PC3 prostate cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). Androgen-independent LNCaP subline C81 was kindly provided by Dr. Ming-Fong Lin (University of Nebraska, Omaha, NE). Immortalized pregnant human myometrial smooth muscle cells (PHM1-41) were a gift from Dr. Barbara Sanborn (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO). RWPE1 cells were maintained in keratinocyte growth medium (Invitrogen). The C81 cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 250 μg/ml gentamycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). DU145 and PC3 cells were maintained in MEM supplemented with 5% FBS. PHM1-41 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Transfection of siRNAs

DU145 and PC3 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well. The next day, cells were transfected with control siRNA or the Giα2-targeting siRNA using the TransIT-TKO transfection reagent. Briefly, MEM (200 μl/well) containing 30 nM of siRNA was mixed with the transfection reagent (8 μl/well) and incubated for 20 min. siRNA mixtures were added drop by drop into 6-well plates. The transfection media were replaced with the regular culture media (2 ml/well) the next day. RNA samples were harvested 72 h after transfection. Protein samples were collected at 72 and 96 h after transfection.

Transfection of plasmid DNAs

MEM (200 μl/well) containing plasmid DNA (2 μg/well) was mixed with lipofectamine 2000 (6 μl/well) and incubated for 30 min. Plasmid DNA mixtures were added drop by drop into 6-well plates. Transfected PC3 cells were cultured for up to 48 h.

Generation of PC3 cell lines ectopically expressing wild type and the siRNA-resistant Giα2

Transfected PC3 cells were placed in 100 mm2 culture dishes and were grown in culture medium supplemented with 600 μg/ml of G418. A week later, cells were maintained in culture medium supplemented with 200 μg/ml of G418. Single colonies were picked and grown in 6-well plates. Expression of Giα2 was verified in total cell lysates by Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis

PC3 cell membranes were prepared as described previously (30). Membrane proteins (50μg) or total cell proteins (100 μg) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes and analyzed for Western blotting as described previously (27). Giα1–3 proteins were detected with isoform-specific antibodies (1:1000 dilution). OXTR was detected in total cell lysates with anti-OXTR antibody (1:1000 dilution). 30 μg of total cell proteins were used for detection of β-actin with a mouse monoclonal antibody (1:10,000 dilution). The signal was detected by ECL (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted from cells using Trizol and the RNA content was determined at 260 nm with a UV spectrophotometer. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA as described previously (27). No-RT control samples were prepared in parallel by replacing reverse transcriptase with RNase.

Expression of Giα1, Giα2, Giα3, GoαA, GoαB and L19 genes was detected with the PCR procedure described previously (27). Specific primers are listed in Table 1. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. DNA bands were visualized under UV light and images were documented using the Bio-Rad gel imager (Hercules, CA).

Table 1.

RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR Primers.

| Genes | Gene ID | Primers | Sequences (5′-3′) | Location | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giα1 | 156071490 | Gi1-F | AGCTGCTGAAGAAGGCTTTA | 673–692 | 171 |

| Gi1-R | GGGATGTAATTTGGTTGAGC | 843–824 | |||

| Giα2 | 49574535 | Gi2-F | AGAACAACCTGAAGGACTGC | 1158–1179 | 173 |

| Gi2-R | GGGAGCTGAGAACAAAGAGA | 1330–1311 | |||

| Giα3 | 169646784 | Gi3-F | TGTTTTAGCTGGCAGTGCT | 481–499 | 169 |

| Gi3-R | CTGGGATATTCTATCCAGATCA | 649–628 | |||

| GoαA | 162461666 | GoA-F | CAAGAAGTCACCTTTGACCA | 1734–1753 | 301 |

| GoA-R | CTACCAGGAGATCAACGTCA | 2034–2015 | |||

| GoαB | 162461737 | GoB-F | AATCCCTGAAGCTTTTTGAC | 1634–1653 | 223 |

| GoB-R | TAGATCTCTTTGTGGGCTGA | 1856–1837 | |||

| L-19 | 68216257 | L-19-F | GAAATCGCCAATGCCAACTC | 306–325 | 406 |

| L-19-R | TCTTAGACCTGCGAGCCTCA | 711–692 |

For quantitative real-time PCR, cDNA samples (1μl) were mixed with 0.2 μM primers and 2X GoTaq qPCR master mix in a final volume of 25 μl in a 96-well PCR plate. PCR detection was performed in an iCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) with procedures described previously (27). Melting curves were examined for the quality of PCR amplification of each sample. Calculations were performed using the ΔΔCt method (27).

Cloning Giα1 and Giα3 genes from PC3 and DU145 cell lines

Open reading frames of Giα1 and Giα3 genes were amplified with the Phusion high-fidelity PCR kit. The shared forward primer was, GCT TGG TAC CAT GGG CTG CAC GTT GAG CGC C. The reverse primer for Giα1 was, TAG ACT CGA GAT GCA TTT TAC CAT GAA CTG CAA. The reverse primer for Giα3 was, GCT TGG TAC CAT GGG CTG CAC GTT GAG CGC C. The PCR procedure was programmed as following: 94°C for 2 min, 30 cycles of the following steps: denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 20 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. A final extension of 10 minutes was followed up after the cycles were completed. Purified PCR products were digested with Kpn I and Xho I and ligated into pcDNA3.1 plasmid. After transformation into XL1-Blue competent cells (Stratagene), five E .Coli colonies containing Giα1- or Giα3-expressing plasmid were grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with ampicillin. Plasmids were harvested with QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen) and sequenced from both ends with the cloning primers.

Luciferase reporter assay

The PC3 cells were harvested from the 6-well plates 24 h after transfection with the pADneo2 C6-BGL plasmid. Aliquots of 30,000 cells were placed in an opaque 96-well plate for different treatments, including control, forskolin (5 μM) and forskolin plus different concentrations of OXT. After treatment for 5 h, 100 μl of steady-glow luciferase detection reagent was added to each well of the 96-well plate. The luciferase activities were detected with OPTIMA LUMIstar plate reader (BMG LABTECH, NC). The results are expressed as percentile of the forskolin-stimulated luciferase activity.

Cell migration assay

In Vitro cell migration assay was performed using 24-well transwell inserts (8 μm) as described previously (27). Briefly, cells were harvested and centrifuged at 500 ×g for 10 min at room temperature. The pellets were resuspended into MEM supplemented with 0.2% BSA at a cell density of 3 × 105 cells/ml. Transwell inserts were treated with rat tail collagen (50 μg/ml) as described previously (27). Chemoattractant solutions were made by diluting OXT (100 nM) or EGF (3 ng/ml) into MEM supplemented with 0.2% BSA. MEM containing 0.2% BSA served as a control medium. Aliquots of 100 μl cell suspension were loaded into transwell inserts and placed into 24-well plates that contained control and chemoattractant solutions (300 μl/well). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 h. Cells inside the transwell inserts were removed by cotton swabs. The cleaned inserts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.5). Cells on the outside of the transwell insert membranes were stained using HEMA 3 staining kit (Fisher Scientific Inc, TX). The number of stained cells was counted as described previously (27). Results were expressed as migration index defined as: the average number of cells per field for test substance/the average number of cells per field for the medium control.

Statistical analysis

Data from multiple independent experiments (n=3–5) are expressed as Mean ± SEM. ANOVA and Duncan’s modified multiple range test were used to examine significance between multiple treatments.

Results

OXT activates the Gi/oα-dependent pathway and induces PC3 cell migration

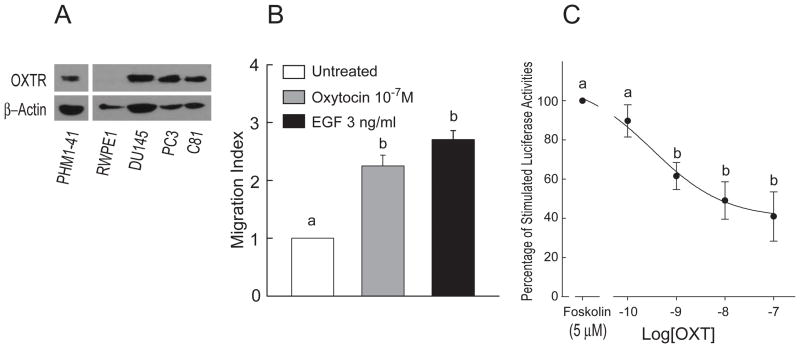

Expression of OXTR is elevated at the mRNA levels in androgen-independent DU145 and PC3 prostate cancer cell lines, compared with normal prostate epithelial cells (27). In the present study, OXTR protein (~70 kDa) was detected in total cell lysates of DU145, PC3 and the androgen-independent subline of LNCaP (C81) prostate cancer cell lines, but not in the cell lysates of immortalized human prostate luminal epithelial cell line (RWPE1) (Fig. 1A). Immortalized pregnant human myometrial smooth muscle cell line (PHM1-41) expresses endogenous OXTR and was used as a positive control (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Oxytocin receptor expression and functions in human prostate cell lines. A, Expression of OXTR was detected with rabbit antibody for OXTR in total cell lysates (50 μg) of RWPE1, DU145, PC3, and C81 cell lines. PHM1-41 expresses endogenous OXTR and was used as a positive control. β-actin was probed on the same blot as sample loading control. B, Treatments with OXT and EGF for 5 h significantly stimulated PC3 cell migration (n=4). C, Twenty-four h after transfection with the cAMP luciferase reporter (pADneo2 C6-BGL), PC3 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of OXT for 10 min before the treatment with forskolin. Luciferase activities were detected 5 h after treatments and expressed as percentage of the forskolin-stimulated luciferase activity (n=3). Data were expressed as Mean ± SEM and analyzed by ANOVA and Duncan’s modified range tests. Significant differences between groups in a given category (P < 0.05) are designated with different lowercase letters.

OXT (100 nM) and EGF (3 ng/ml) induced PC3 cell migration (Fig. 1B). This effect of OXT has been shown to be sensitive to PTx pretreatment, suggesting the involvement of Gi/oα-proteins (27). Inhibiting cAMP accumulation is the canonical function of Gi/oα-proteins. PC3 cells were transfected with the pADneo2 C6-BGL plasmid containing a cAMP-responsive luciferase reporter. Forskolin (5 μM) induced a three-fold increase in luciferase activities in the transfected PC3 cells. Treatment with OXT caused a dose-dependent inhibition of forskolin-stimulated luciferase activity (Fig. 1C), which supports the involvement of Gi/oα in OXTR signaling in PC3 cells.

Giα2 is important for the OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells

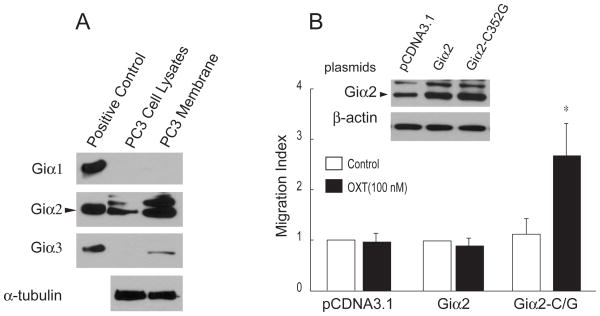

Expression of Gi/oα isoforms was detected by RT-PCR with specific primers listed in Table 1. Giα1, Giα2, and Giα3 were the predominant Gi/oα family members that are expressed at the mRNA levels in PC3 cells (data not shown). Because G-proteins are enriched in the cell membranes (5), the membrane fractions were prepared from PC3 cells to determine the expression of Giα1–3 proteins. Total lysates (100 ng) of E. coli expressing recombinant rat Giα1–3 proteins were used as positive controls. As shown in Fig. 2A, specific antibodies for Giα1–3 proteins were able to detect respective recombinant proteins. Giα2 was the only Giα family member that was detected in PC3 total cell lysates and membrane fractions (Fig. 2A). In comparison, trace levesl of Giα3 protein were detected in only membrane fraction while Giα1 was undetectable in both total cell lysates and membrane fractions (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Giα2 is potentially important for the OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells. A, Total cell lysates and membrane fractions from PC3 cells were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Recombinant rat Giα1–3 were used as positive controls. α-tubulin was detected as a sample loading control for both cell lysates and membranes. Similar results were observed with two separate membrane preparations. B, PC3 cells were treated with PTx (200 ng/ml) 24 h after transfection with pCDNA3.1, wild type Giα2 and the Giα2-C352G mutant. The next day, transfected PC3 cells were treated with OXT in a transwell migration assay. OXT induced cell migration only in the PC3 cells that were transfected with the Giα2-C352G mutant. Protein levels of Giα2 in cells transfected with empty vector, inGiα2 and the Giα2-C352G mutant in total cell lysates are shown in the upper panel. Data were expressed as Mean ± SEM (n=3) and analyzed by t-test (* P < 0.05).

Mutations causing codon shift might occur in open reading frames of Giα1 and Giα3 genes, which could account for the absence of Giα1 and Giα3 proteins in PC3 cells. Open reading frames of Giα1 and Giα3 genes were cloned by RT-PCR from total RNA samples of PC3 and DU145 cells. DNA sequencing did not identify any mutations in protein coding regions of both genes, indicating that wild type Giα1 and Giα3 are expressed in DU145 and PC3 cell lines.

Substitution of the C352 for G results in a PTx-resistant Giα2 mutant that retains the ability to transmit signaling of GPCRs (9). PC3 cells were transiently transfected with wild type Giα2 and the Giα2-C352G mutant. Expression of wild type Giα2 and the Giα2-C352G are shown in Fig. 2B (upper panel). After pretreatment with PTx (200 ng/ml) overnight, OXT (100 nM) treatment induced cell migration only in the PC3 cells that were transfected with the Giα2-C352G mutant (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that activated OXTR couples with Giα2 protein to exert OXT-induced PC3 cell migration.

The endogenous Giα2 is essential for migration of prostate cancer cells

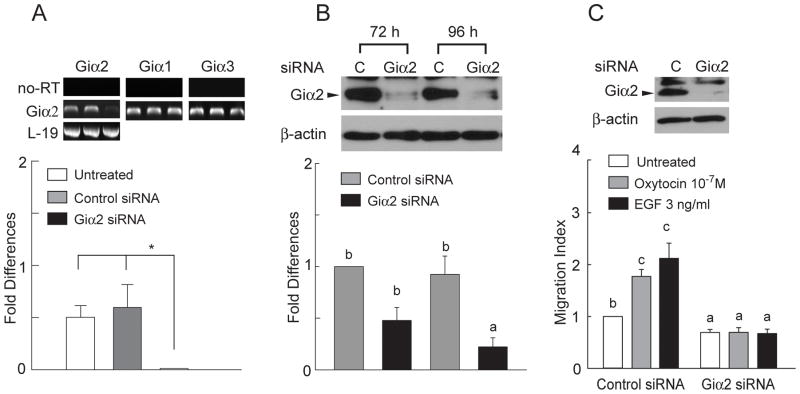

Control and Giα2-targeting siRNAs were transfected into PC3 cells. RNA samples were harvested 72 h after transfection. Total cell proteins were harvested at 72 and 96 h after transfection. As shown in Fig. 3A, Giα2 mRNAs were the least abundant among the three Giα isoforms in PC3 cell line. Control siRNA did not affect mRNA levels of Giα1–3 in these cells. The Giα2-targeting siRNA specifically reduced Giα2 mRNAs by 96% in this cell line (Fig. 3A). This Giα2-targeting siRNA caused a significant reduction (~75%) in Giα2 protein levels in PC3 cells at 72 and 96 h after transfection (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Giα2-targeting siRNA specifically silences expression of Giα2 in PC3 cells. A, RNA samples from PC3 cells were harvested 72 h after transfection with control and Giα2-targeting siRNAs. Giα1–3 mRNA levels were detected with RT-PCR and real time RT-PCR. No-RT samples were made by substitution of reverse transcriptase with RNase. Control siRNA did not affect mRNA levels of Giα1–3, the Giα2-targeting siRNA specifically reduced Giα2 mRNAs by 96%. L-19 gene was amplified as a template control. B, Total cell lysates from PC3 cells were harvested at 72 and 96 h after siRNA transfection. β-actin was detected as a sample loading control. Band density was quantified and fold changes over 72 h control siRNA treatment were calculated. Data were expressed as Mean ± SEM (A and B, n=3) and analyzed by ANOVA and Duncan’s modified range tests. C, Endogenous Giα2 are important for PC3 cell migration. OXT as well as EGF induced cell migration in the PC3 cells that were treated with control siRNA. These effects of OXT and EGF were completely eliminated in the PC3 cells that were treated with the Giα2-targeting siRNA. Total cell lysates from PC3 cells were harvested after siRNA transfection followed by Western blot analysis with Giα2 antibody. β-actin was detected as a sample loading control. Data were summarized as Mean ± SEM (n=5) and analyzed by ANOVA and Duncan’s modified range tests. Significant differences between groups in a given category (P < 0.05) are designated with different lowercase letters.

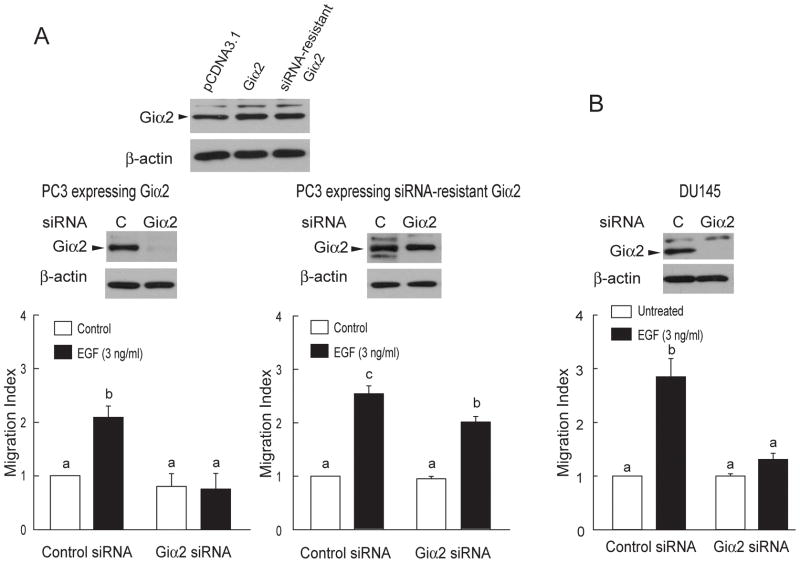

OXT and EGF induced cell migration in the PC3 cells that were pretreated with control siRNA (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, these effects of OXT and EGF were completely eliminated in the PC3 cells treated with the Giα2-targeting siRNA (Fig. 3C). Inhibition of EGF-induced cell migration by the Giα2-targeting siRNA was unexpected. To further examine whether Giα2 has a specific role in the EGF-induced cell migration, PC3 stable cell lines were generated to ectopically express wild type Giα2 and the siRNA-resistant Giα2 genes (Fig. 4A). The Giα2-targeting siRNA completely eliminated EGF-induced cell migration in the PC3 cells that ectopically expresses wild type Giα2 (Fig. 4A). However, the Giα2-targeting siRNA failed to inhibit effects of EGF on migration of PC3 cells that expressed the siRNA-resistant Giα2 gene (Fig. 4A). These data clearly support a critical role of Giα2 in EGF effects on cell migration. We have previously shown that EGF induces migration of DU145 prostate cancer cells while these cells are not responsive to OXT effects on cell migration (27). The Giα2-targeting siRNA, which caused a 93% reduction of Giα2 protein levels, blocked EGF-induced cell migration in DU145 cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Endogenous Giα2 plays a specific role in EGF-induced migration of prostate cancer cells. A, Expression of Giα2 was detected in total cell lysates from PC3 stable cell lines that ectopically express wild type Giα2 or the siRNA-resistant Giα2 genes. Total cell lysates from these cells were collected after Giα2-targeting siRNA followed by Western blot analysis with Giα2 antibody. β-actin was detected as a sample loading control. The effect of EGF on cell migration was blocked by the Giα2-targeting siRNA in the PC3 cells that ectopically expresses wild type Giα2. However, this effect of EGF became insensitive to the Giα2-targeting siRNA in the PC3 cell that expresses the siRNA-resistant Giα2. B, The Giα2-targeting siRNA blocked EGF-induced migration of DU145 cells. Total cell lysates from DU145 cells were harvested after siRNA transfection followed by Western blot analysis with Giα2 antibody. β-actin was detected as a sample loading control. Data were expressed as Mean ± SEM (A, n=3. B, n=4) and analyzed by ANOVA and Duncan’s modified range tests. Significant differences between groups in a given category (P < 0.05) are designated with different lowercase letters.

Discussion

OXT is a peptide hormone that regulates normal prostate functions (22–24). However, the information is very limited on the effects of OXT on prostate cancer progression. In the present study, OXTR protein was detected only in prostate cancer cell lines, although OXTR mRNA is expressed in normal and prostate cancer cell lines (27). OXTR was also detected in the PHM1-41 cell lines that express endogenous OXTR (31). These data indicate that expression of OXTR is amplified in prostate cancer cells. Immunohistochemistry staining for OXTR has shown that expression of OXTR is negative in normal human prostate epithelium (26). However, OXTR has been shown to be expressed in hyperplastic as well as neoplastic prostate epithelium and to be increased in the neoplastic tissues when compared with the hyperplastic tissues (25). The expression profile of OXTR in normal and prostate cancer cell lines reflects its expression in human prostate in normal and disease states. Bioinformatic mining of Oncomine microarray database (www.oncomine.org) has shown that expression of OXTR is significantly increased in metastatic prostate cancer specimens when compared with normal prostate specimens (32).

OXTR couples to multiple G-proteins including Gq and Gi. In turn, these G-proteins may convey OXT signaling to different intracellular pathways leading to distinct cellular functions (33). Activated OXTR has been shown to induce migration of PC3 cells (27). This effect of OXT is sensitive to PTx pretreatment, indicating the involvement of Gi/o-dependent signaling (27). Inhibition of the intracellular cAMP accumulation is the canonical function of activated Gi/o-proteins (5). By employing a luciferase reporter assay to monitor changes in intracellular cAMP levels, we show that OXT caused a dose-dependent inhibition of forskolin-induced luciferase activity. Hence, OXT activates Gi/o-dependent pathways in PC3 cells.

OXTR has been shown to couple to Giα3 in pregnant rat myometrium (29). Nevertheless, there is no evidence that excludes OXTR from coupling to other Gi/oα family members. In fact, OXTR has recently been shown to couple to all of the Gi/oα isoforms in transfected HEK293 cells (34). Expression of Gi/oα isoforms has not been characterized in normal and prostate cancer cell lines. Although Giα1–3 were the predominant Gi/oα family members that were expressed at the mRNA levels in PC3 cells, Giα2 was most abundant isoform which was detected at the protein level in this cell line. Trace amounts of Giα3 protein were detected in the membrane fraction while Gia1 protein was completely absent in these cells. This finding cannot be explained by differential regulation of Giα1–3 mRNAs because Giα2 mRNA was expressed at the lowest level among the three Giα isoforms in PC3 cells. Another possibility is that there might be mutations to cause codon shift in the coding regions of Giα1 and Giα3 genes. However, this proved not to be the case because wild type Giα1 and Giα3 genes were identified in PC3 cells. Therefore, both Giα1 and Giα3 could be diminished in PC3 cells by an unknown post-transcriptional mechanism, which will be studied in the future. In accordance with the present finding, Giα3 protein has been shown to be diminished in primary prostate cancer specimens (35). Ectopic expression of the Giα2-C352G mutant reversed the inhibition by PTx of OXT-induced cell migration in the transfected PC3 cells, suggesting that OXTR couples to Giα2 that may mediate the OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells. To investigate whether the endogenous Giα2 was involved in the OXTR-regulated PC3 cell migration, we employed a specific siRNA to silence expression of Giα2 gene. The Giα2-targeting siRNA eliminated the Giα2 mRNA by 96%, but did not alter Giα1 and Giα3 mRNA levels in PC3 cells. A 93% reduction in Giα2 mRNA was also observed in DU145 cells that were treated with the Giα2-targeting siRNA. These data indicate that the Giα2-targeting siRNA is very effective in knocking down expression of Giα2 mRNAs in both PC3 and DU145 cell lines. The Giα2-targeting siRNA significantly blocked the expression of Giα2 protein in PC3 cells, compared with the control siRNA-treated group. Under the validated condition, the Giα2-targeting siRNA completely inhibited the OXT-induced cell migration in PC3 cells. This data indicates that the endogenous Giα2 is required for the OXT-induced migration of PC3 cells. The Giα2-targeting siRNA was also shown to inhibit EGF-induced cell migration in both PC3 and DU145 cell lines. Both Giα1 and Giα3 have been shown to play important roles in EGF-induced cell migration (36, 37). However, our study has provided the first line of evidence supporting a similar role of Giα2 in EGF function. Giα2 plays a specific role, because the Giα2-targeting siRNA was no longer effective to block the EGF-induced cell migration in the PC3 cell line that expresses a siRNA-resistant Giα2 gene. Despite the fact that there is no comprehensive picture about how Giα2 is integrated in the EGF signaling, Giα2 appears to play an essential role in prostate cancer cell migration in response to EGF. Our knockdown studies also indicate that the trace amounts of Giα3 protein are unable to rescue oxytocin or EGF-induced cell migration in the absence of Giα2 protein.

In summary, the present study has provided direct evidence that support the expression of OXTR in prostate cancer cell lines. OXT treatment has been shown to activate the Gi/oα-dependent signaling. Giα2 is the most abundant member of the Gi/oα family that is detected at the protein level in PC3 cells. Endogenous Giα2 is required for OXT- as well as EGF-induced cell migration in prostate cancer cells. These data suggest that Giα2 plays an essential role in prostate cancer cell migration.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by NIH (RCMI 5G12RR003062 and NIMHD 1P20MD002285-01) and Georgia Research Alliance.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Hamm HE, Gilchrist A. Heterotrimeric G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:189–96. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neer EJ. Heterotrimeric G proteins: organizers of transmembrane signals. Cell. 1995;80:249–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offermanns S, Simon MI. Organization of transmembrane signalling by heterotrimeric G proteins. Cancer Surv. 1996;27:177–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehrl JH. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling: roles in immune function and fine-tuning by RGS proteins. Immunity. 1998;8:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilman AG. Nobel Lecture. G proteins and regulation of adenylyl cyclase. Biosci Rep. 1995;15:65–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01200143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huff RM, Axton JM, Neer EJ. Physical and immunological characterization of a guanine nucleotide-binding protein purified from bovine cerebral cortex. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10864–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sternweis PC, Robishaw JD. Isolation of two proteins with high affinity for guanine nucleotides from membranes of bovine brain. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13806–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaslow HR, Burns DL. Pertussis toxin and target eukaryotic cells: binding, entry, and activation. Faseb J. 1992;6:2684–90. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.9.1612292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senogles SE. The D2 dopamine receptor isoforms signal through distinct Gi alpha proteins to inhibit adenylyl cyclase. A study with site-directed mutant Gi alpha proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23120–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tasseff R, Nayak S, Salim S, Kaushik P, Rizvi N, Varner JD. Analysis of the molecular networks in androgen dependent and independent prostate cancer revealed fragile and robust subsystems. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah RB, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM, Shen R, Ghosh D, Zhou M, et al. Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a heterogeneous group of diseases: lessons from a rapid autopsy program. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9209–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craft N, Chhor C, Tran C, Belldegrun A, DeKernion J, Witte ON, et al. Evidence for clonal outgrowth of androgen-independent prostate cancer cells from androgen-dependent tumors through a two-step process. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5030–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daaka Y. G proteins in cancer: the prostate cancer paradigm. Sci STKE 2004. 2004:re2. doi: 10.1126/stke.2162004re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly P, Stemmle LN, Madden JF, Fields TA, Daaka Y, Casey PJ. A role for the G12 family of heterotrimeric G proteins in prostate cancer invasion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26483–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao X, Qin J, Xie Y, Khan O, Dowd F, Scofield M, et al. Regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) inhibits androgen-independent activation of androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:3719–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasbohm EA, Guo R, Yowell CW, Bagchi G, Kelly P, Arora P, et al. Androgen receptor activation by G(s) signaling in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11583–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terada N, Shimizu Y, Kamba T, Inoue T, Maeno A, Kobayashi T, et al. Identification of EP4 as a potential target for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer using a novel xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1606–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff DW, Xie Y, Deng C, Gatalica Z, Yang M, Wang B, et al. Epigenetic repression of regulator of G-protein signaling 2 promotes androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1521–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kue PF, Daaka Y. Essential role for G proteins in prostate cancer cell growth and signaling. J Urol. 2000;164:2162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson BD, Jin Y, Wu KH, Colvin RA, Luster AD, Birnbaumer L, et al. Inhibition of G alpha i2 activation by G alpha i3 in CXCR3-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9547–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610931200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assinder SJ, Johnson C, King K, Nicholson HD. Regulation of 5alpha-reductase isoforms by oxytocin in the rat ventral prostate. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5767–73. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodanszky M, Sharaf H, Roy JB, Said SI. Contractile activity of vasotocin, oxytocin, and vasopressin on mammalian prostate. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;216:311–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90376-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plecas B, Popovic A, Jovovic D, Hristic M. Mitotic activity and cell deletion in ventral prostate epithelium of intact and castrated oxytocin-treated rats. J Endocrinol Invest. 1992;15:249–53. doi: 10.1007/BF03348721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cassoni P, Marrocco T, Sapino A, Allia E, Bussolati G. Evidence of oxytocin/oxytocin receptor interplay in human prostate gland and carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frayne J, Nicholson HD. Localization of oxytocin receptors in the human and macaque monkey male reproductive tracts: evidence for a physiological role of oxytocin in the male. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:527–32. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong M, Boseman ML, Millena AC, Khan SA. Oxytocin induces the migration of prostate cancer cells: involvement of the Gi-coupled signaling pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:1164–72. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baek KJ, Kwon NS, Lee HS, Kim MS, Muralidhar P, Im MJ. Oxytocin receptor couples to the 80 kDa Gh alpha family protein in human myometrium. Biochem J. 1996;315 (Pt 3):739–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strakova Z, Soloff MS. Coupling of oxytocin receptor to G proteins in rat myometrium during labor: Gi receptor interaction. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E870–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.5.E870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong M, Navratil AM, Clay C, Sanborn BM. Residues in the hydrophilic face of putative helix 8 of oxytocin receptor are important for receptor function. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3490–8. doi: 10.1021/bi035899m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monga M, Ku CY, Dodge K, Sanborn BM. Oxytocin-stimulated responses in a pregnant human immortalized myometrial cell line. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:427–32. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Cao X, Wang L, Dhanasekaran SM, et al. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reversi A, Rimoldi V, Marrocco T, Cassoni P, Bussolati G, Parenti M, et al. The oxytocin receptor antagonist atosiban inhibits cell growth via a “biased agonist” mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16311–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busnelli M, Sauliere A, Manning M, Bouvier M, Gales C, Chini B. Functional selective oxytocin-derived agonists discriminate between individual G protein family subtypes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3617–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prieto Villapun JC, Solano Haro RM, Carmena Sierra MJ, Sanchez-Chapado M. Importance of heterotrimeric G proteins in prostate cancer molecular biology. Actas Urol Esp. 2005;29:948–54. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(05)73375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao C, Huang X, Han Y, Wan Y, Birnbaumer L, Feng GS, et al. Galpha(i1) and Galpha(i3) are required for epidermal growth factor-mediated activation of the Akt-mTORC1 pathway. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra17. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghosh P, Beas AO, Bornheimer SJ, Garcia-Marcos M, Forry EP, Johannson C, et al. A G{alpha}i-GIV molecular complex binds epidermal growth factor receptor and determines whether cells migrate or proliferate. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2338–54. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]