Abstract

Investigations employing wearable monitors have begun to examine how sedentary time behaviors influence health.

Purpose

To demonstrate the utility of a measure of sedentary behavior and to validate the activPAL and ActiGraph GT3X for estimating measures of sedentary behavior: absolute number of breaks and break-rate.

Methods

Thirteen participants completed two, 10-hour conditions. During the baseline condition, participants performed normal daily activity and during the treatment condition, participants were asked to reduce and break-up their sedentary time. In each condition, participants wore two ActiGraph GT3X monitors and one activPAL. The ActiGraph was tested using the low frequency extension filter (AG-LFE) and the normal filter (AG-Norm). For both ActiGraph monitors two count cut-points to estimate sedentary time were examined: 100 and 150 counts∙min−1. Direct observation served as the criterion measure of total sedentary time, absolute number of breaks from sedentary time and break-rate (number of breaks per sedentary hour [brks.sed-hr−1]).

Results

Break-rate was the only metric sensitive to changes in behavior between baseline (5.1 [3.3 to 6.8] brks.sed-hr−1) and treatment conditions (7.3 [4.7 to 9.8] brks.sed-hr−1) (mean [95% CI]). The activPAL produced valid estimates of all sedentary behavior measures and was sensitive to changes in break-rate between conditions (baseline: 5.1 [2.8 to 7.1] brks.sed-hr−1, treatment: 8.0 [5.8 to 10.2] brks.sed-hr−1). In general, the AG-LFE and AG-Norm were not accurate in estimating break-rate or absolute number of breaks and were not sensitive to changes between conditions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the utility of expressing breaks from sedentary time as a rate per sedentary hour, a metric specifically relevant to free-living behavior, and provides further evidence that the activPAL is a valid tool to measure components of sedentary behavior in free-living environments.

Keywords: Sedentary behavior, Breaks, Activity monitors, activPAL, ActiGraph

Introduction

Sedentary behaviors are defined as seated or reclining postures that require low levels of energy expenditure (e.g. < 1.5 METS) (24), and they comprise 55 to 70% of waking hours (22). Strong epidemiological evidence suggests sedentary behaviors, independent of physical activity, are associated with a host of poor health outcomes, including increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality. Although these relationships have been predominantly established using self-reported surrogate measures of sedentary time (e.g. TV viewing time), studies using objective measures also support these findings (2, 3, 8, 14–17, 20). Using accelerometers to obtain global measures of total sedentary time, results from cross-sectional studies indicate sedentary behaviors are associated with increased risk for abnormal glucose and lipid metabolism, obesity and several chronic diseases (8, 14, 17, 20).

Several animal and human studies indicate that in addition to total sedentary time, how one breaks up sedentary time may influence the muscular, cardiovascular and metabolic responses to sedentary behavior (1, 12, 15, 29). Advances in accelerometer-based activity monitors have allowed researchers to investigate how breaks from sedentary time affect health in free-living humans. Using the ActiGraph GT1M accelerometer Healy and colleagues reported frequent breaks from sedentary time (i.e., sit-to-stand transitions) are beneficially associated with adiposity, triglycerides, and 2-hour plasma glucose, independent of total sedentary time and physical activity (15). Data from the National Health and Examination Survey (NHANES) survey indicate more breaks from sitting are also associated with a smaller waist circumference and lower c-reactive protein levels (16). The observation that taking frequent breaks from sedentary behaviors attenuates the negative physiologic response is further supported by work from Chastin and colleagues (2, 3). Using the activPAL monitor to assess sedentary time, there was no difference in total sedentary time between healthy individuals and individuals with chronic health conditions. However, there were significant differences in how sedentary time occurred between groups (2, 3).

These data provide evidence that “breaks from sitting” may be an appropriate target for behavioral interventions. Encouraging individuals to “break-up” and accumulate shorter bouts of sedentary time may be a feasible strategy for intervention recommendations. However, prior to establishing recommendations and implementing interventions, validity of wearable devices to detect breaks during free-living behavior must be determined. In laboratory studies, the activPAL was validated to estimate time in different postures (11), step count (21, 26), static and dynamic behaviors (10) and sit-to-stand transitions (11). In free-living conditions, the activPAL produced highly accurate and precise estimate of total sedentary time (18). Given these data, it seems reasonable to suggest that the activPAL will accurately identify breaks from sedentary time in free-living settings, however this has yet to be determined. Conversely, evidence suggests that the ActiGraph will be not be able to identify breaks from sedentary time given its biased and imprecise estimates of total sedentary time (18). The ActiGraph is traditionally used to quantify time spent in different intensities of activity by summing time above or below specified count thresholds. This method, known as the cut-point method (9), works reasonably well for identifying moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), but is less accurate for distinguishing sedentary and light intensity activities (18, 19). In the context of sedentary behavior measurement, this method is inherently limited in that it estimates intensities, not posture. However, the validity of the ActiGraph in identifying breaks from sedentary time has yet to be tested. This is of particular importance given the ActiGraph was the tool used in all studies providing evidence that breaks from sedentary time may be beneficial for health (15, 16). Thus, an empirical evaluation and comparison of both tools will further inform research aiming to measure and interpret sedentary behavior and its associated health outcomes.

As the first step for this validation, a suitable metric to describe breaks from sedentary time in free-living environments must be established. In cohort or etiologic studies where the goal is to relate a characteristic of sedentary behavior (e.g. total amount of sedentary time, total number of breaks from sedentary time) to a specific health outcome, it is appropriate to measure and statistically evaluate the independent, additive and interactive effects of different features of sedentary behavior. This is easily done in statistical models. Conversely, when measuring behavioral changes subsequent to an intervention, or establishing recommendations regarding sedentary behavior, it may be more appropriate to use a composite measure of sedentary behavior that collectively assesses changes in both total sedentary time and breaks from sedentary time. For example, in intervention studies where sedentary time decreases, the opportunity to accumulate breaks also decreases. Thus, change in absolute number of breaks may not be sensitive to important behavioral changes consequent to an intervention. In contrast, if breaks are expressed as a rate per sedentary hour, the overall effects of the intervention may be more readily detected. Additionally, a composite measure of sedentary behavior, such as breaks per sedentary hour is ecologically relevant and may be easily translated for public health recommendations.

This study had three specific aims. Aim one was to express breaks from sedentary time as a metric specifically relevant to free-living sedentary behavior and to compare this metric with absolute number of breaks. The metric, called “break-rate,” is a measure of the rate of breaks per sedentary hour (brks.sed-hr−1). Aim two was to validate the performance of the ActiGraph GT3X and activPAL to estimate absolute number of breaks and break-rate. Aim three was to determine if the ActiGraph GT3X and activPAL are sensitive enough to detect the effects of an intervention to reduce and break-up sedentary time.

Methods

Eligibility and Recruitment

Thirteen participants were recruited from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and local communities. Eligible participants were between the ages of 20–60 years and satisfied the Physical Activity Guideline of accumulating at least 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity activity (4). Participants were healthy and free from any musculoskeletal problems that would compromise their ability to change how they accumulate sedentary time.

Participants reported to the University of Massachusetts and signed an Informed Consent Document approved by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board. Following the consenting process, height (to the nearest 0.1 cm) and weight (to the nearest 0.1kg) were measured using a floor scale/stadiometer (Detecto; Webb City, MO). To determine initial eligibility, participants completed a health history questionnaire and a physical activity status questionnaire. To verify self-reported activity level, participants wore the ActiGraph GT3X for seven consecutive days. These data were analyzed using the Freedson cut-points to determine time spent in moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) per week (9). If MVPA was less than 150 minutes, participants were excluded from the study.

Experimental Procedures

Free-living behavior was monitored for approximately 10 consecutive hours, on two separate days. For the first monitoring day, participants were asked to perform their normal daily activity, including their normal exercise routine and normal activities of daily living (baseline condition). For the second monitoring day, they were asked to decrease their total sedentary time and to break-up sedentary behaviors as much as possible (treatment condition). Participants were not provided a specific prescription to reduce and break-up their sedentary time, but were provided suggestions and examples of how to decrease sedentary time within their natural, free-living environment. For example, if they normally spent the majority of their working day seated at a desk, they were encouraged to make standing workstations so they could easily alternate between sitting and standing. Other suggestions included standing during television commercials, standing to answer the phone and standing while eating. The baseline and treatment conditions were performed at least 24-hours apart, and no more than two-weeks separated the two conditions.

Criterion Measure: Direct Observation

In each condition, direct observation served as the criterion measure to assess total sedentary time and breaks from sedentary time. In the morning a trained observer met the participants in their natural environment (e.g. place of work, school, home). Participants were then observed for approximately 10 consecutive hours. A hand-held personal digital assistant (PDA) programmed for focal sampling and duration coding was used to record participant behavior. Every time body position changed (e.g. went from sitting to standing) the observer recorded this in the PDA. Each entry was time stamped and the length of each behavior bout was automatically recorded in the PDA. The start and stop of each behavior recorded by the direct observer was exported from the PDA using custom software (Noldus: Observer 9.0). During the 10-hour observation, participants were allowed to have “private time” when needed. Reasons for “private time” included behaviors such as using the restroom and changing clothes. During these activities, the observer coded “private” on the PDA.

The DO PDA hardware (Noldus: Pocket Observer) and software (Noldus: Observer 9.0) used to conduct the direct observation are commercially available tools (Noldus Information Technology; Netherlands). The software was programmed to capture specific behaviors of interest (e.g. sitting, standing). Observers worked in 2–4 hour shifts and a total of three different observers completed all of the observation sessions for each participant. Observers completed extensive verbal, written and video training and testing before observing participants in a free-living environment. The training material focused on a specific protocol to avoid disrupting free-living behavior and to accurately record sedentary time and breaks from sedentary time. Upon completion of training, the ability of each observer to identify activity type (e.g. sit, stand, walk) and intensity (e.g. 3 METs) was tested using a ~15 minute video of free-living behavior. The video was first coded by a group of experienced observers and study observer responses (activity type and MET value) were compared with the experienced observers’ responses using a Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ). To be considered “in agreement” study observers needed to correctly identify both the type and intensity of the activity. There was a very high level of agreement between the study observers’ responses and the experienced observers’ responses (mean κ = 0.92).

Activity Monitors. Data Synchronization

A start/stop record was generated to record the start and stop times for each observation period using the custom Noldus software. The start/stop record was then used to process each of the activity monitor files using a custom R program (27). The monitor data corresponding directly with the start and stop times of direct observation were then extracted from the monitor file. The monitors were initialized on the same file as the computer; therefore the activity monitor files were matched second-by-second with the direct observation time-stamp. Behaviors coded as “private” by the observer along with the corresponding activity monitor data were eliminated from the analyses.

ActiGraph

Each participant wore two GT3X monitors programmed to collect data from the vertical axis in one-second epochs. One was initialized using the low frequency extension (AG-LFE) and the other was initialized with the normal filter (AG-Norm). For both the AG-LFE and AG-Norm two count cut-points to estimate sedentary time were examined: 100 counts∙min−1 (AG-LFE-100 and AG-Norm-100, respectively) and 150 counts∙min−1 (AG-LFE-150 and AG-Norm-150, respectively). The 100 counts∙min−1 cut-point is the predominant cut-point used by researchers (5, 13, 15, 18, 23). However, Kozey-Keadle et al. recently reported 150 counts∙min−1 may be a more appropriate cut-point to identify sedentary time from the ActiGraph monitor (18). The AG-LFE and AG-Norm were worn on a belt with the AG-LFE positioned directly on the anterior-supra-iliac spine and the AG-Norm positioned immediately distal to the AG-LFE. A custom R program was used to generate total sedentary time, breaks and break-rate from the AG monitor.

activPAL

Participants wore the activPALs on their right thighs. It was attached using a non-allergenic adhesive pad and positioned on the midline of the thigh, one-third of the way between the hip and knee. The time-stamped “event” data file from the activPAL software (version 5.8.5) was used to identify the duration of each sitting/lying, standing and stepping bout. The event file was converted to second-by-second data using an R program to synchronize data with the DO file.

Data Cleaning

For aims one and three, direct observation data and valid monitor data from all three monitors were required for a participant to be included in the analyses. For aim two, valid data from all monitors were not required. For example, if a participant had valid activPAL and AG-LFE data, but not AG-Norm, only the AG-Norm analyses were eliminated.

Data Reduction

Operational definitions for total sedentary time and absolute number of breaks for the criterion (direct observation) and each activity monitor were as follows:

- Direct Observation

- Total sedentary time (hours) – The sum of the duration of behavior that was coded as sitting or lying.

- Break from sedentary time – Any instance where a sitting or lying behavior was followed by a non-sitting or non-lying behavior.

- activPAL – Output from the activPAL was downloaded using the “Event” data in the activPAL software. These data provide information about the start time and duration of each sitting/lying, standing and stepping bout.

- Total sedentary time (hours) – Determined by summing the duration of all sitting/lying bouts.

- Break from sedentary time – Any instance where a sitting/lying bout was followed by a standing or stepping bout.

- AG-LFE and AG-Norm

- Total sedentary time (hours) – Determined by summing the minutes where counts∙min−1 were less than the cut-point of interest (e.g. counts∙min−1 < 100).

- Break from sedentary time – Any instance where a minute identified as sedentary (e.g. counts∙min−1 < 100) was followed by a minute identified as not sedentary (e.g. counts∙min−1 ≥ 100).

Data from each measurement method were used to calculate break-rate. Break-rate was calculated by dividing absolute number of breaks by total hours spent sedentary (brks.sed-hr−1).

Statistical Evaluation

All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical computing environment (27). To address aim one, we computed and compared the break-rate for the criterion and each prediction method. We used a repeated measures linear mixed model and likelihood ratio tests to evaluate the sensitivity of these metrics to detect the possible effects of the intervention on measures of sedentary behavior. The repeated measures model was used to account for possible intra-individual correlation. The likelihood ratio test examined if the addition of condition (baseline/treatment) as an independent variable resulted in a significantly better fit.

To address aim two we used two statistical tools: percent bias and precision. The percent bias, or mean difference between predicted and criterion estimates (Σ[(predicted break-rate − criterion break-rate)/criterion break-rate]/N), is a measure of accuracy and gives information about the systematic error of the prediction. We expressed bias as a percent of the criterion to compare estimates between conditions and allow the size of the error to be proportional to the quantity that is measured. In this study a negative bias indicated underestimation by the prediction method; a positive bias indicated overestimation by the prediction method. Precision is the inverse of variance and provides information about the size of the random error of the prediction. To evaluate precision we determined the ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for the differences between the predictions and the criterion (bias). Use of the 95% CI allowed us to do two things. The width of the CI is proportional to the standard error of the differences; a small CI width indicated a high precision and a large CI width indicated a low precision. Additionally, if the upper and lower CI’s of the bias spanned zero, then the predicted estimate was not significantly different from the criterion at α=0.05. We used the 95% CI and standard error instead of standard deviation because we were interested in how these metrics performed in a population, not for a specific individual. We note that a confidence interval bias that does not include zero does not necessarily indicate that a measure is unbiased; instead one may not have the power to detect a bias of a certain size.

To address aim three we used a repeated measures linear mixed model with likelihood ratio testing. We fit separate models for the criterion, the activPAL and each AG-LFE and AG-Norm cut-point.

Results

Thirteen participants (4 males, 9 females) completed the study. Participants’ mean (± SD) age was 24.8 (5.2) years and mean (± SD) BMI was 23.8 (1.9) kg.m−2. Of the thirteen participants enrolled in the study, one participant’s AG-LFE and AG-Norm monitors did not record data. A second participant’s AG-Norm did not record data. These observations were eliminated from the analyses for aims one and three (n=11). For aim two, this resulted in a total of 234.8 hours of direct observation with corresponding AG-LFE data (mean hours per observation=9.4 [n=12]), 234.2 hours of direct observation with corresponding AG-Norm data (mean hours per observation=9.8 [n=11]) and 251.5 hours of direct observation with corresponding activPAL data (mean hours per observation=9.7 [n=13]).

For aim one we expressed breaks from sedentary time as a rate of breaks per sedentary hour and compared this metric to absolute number of breaks. In Table 1 we report the mean (95% CI) total sedentary time, absolute number of breaks and break-rate identified by direct observation. In the baseline condition, participants spent 6.3 (5.7–7.0) hours in sedentary behavior and took 30.9 (22.2–39.6) breaks from sedentary time. This resulted in a break-rate of 5.1 (3.3–6.8) brks.sed-hr−1. Participants significantly decreased total sedentary time during the treatment condition to 4.5 (3.6–5.4) hours. However, there was no change in the absolute number of breaks (27.8 [20.5–35.1]) (p > 0.05), resulting in a significant increase in break-rate to 7.3 (4.7–9.8) brks.sed-hr−1 (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Active and sedentary behaviors identified by direct observation (mean 95% CI)

| Baseline Condition | Treatment Condition | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sedentary Time (hrs.) | 6.3 (5.7–7.0) | 4.5 (3.6–5.4)* |

| Absolute Number of Breaks | 30.9 (22.2–39.6) | 27.8 (20.5–35.1) |

| Break-Rate (brks.sed-hr−1) | 5.1 (3.3–6.8) | 7.3 (4.7–9.8)* |

| Total Standing Time (hrs.) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1)* |

| Total Stepping Time (hrs.) | 2.4 (2.1–2.7) | 3.6 (3.1–4.2)* |

| Number of Sedentary Bouts | 31.5 (24.1–38.9) | 29.2 (22.0–36.4) |

| Number of Standing Bouts | 44.0 (31.7–56.3) | 64.9 (37.8–92.0) |

| Number of Stepping Bouts | 66.4 (53.2–79.6) | 85.2 (56.4–114.0) |

| Duration of Sedentary Bouts (min) | 42.8 (29.5–56.1) | 36.9 (21.3–52.5) |

| Duration of Standing Bouts (min) | 5.9 (3.6–8.2) | 8.1 (3.6–12.6) |

| Duration of Stepping Bouts (min) | 13.3 (10.3–16.3) | 21.4 (10.9–31.9) |

| Percent of Sedentary Bouts ≥ 20-minutes (%) | 25.5 (14.8–36.2) | 14.6 (7.1–22.1)* |

Significantly different than baseline p<0.05

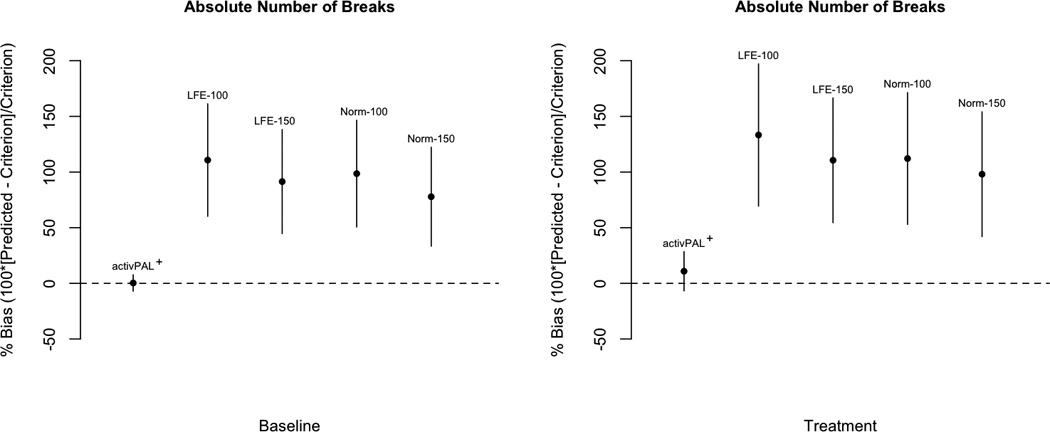

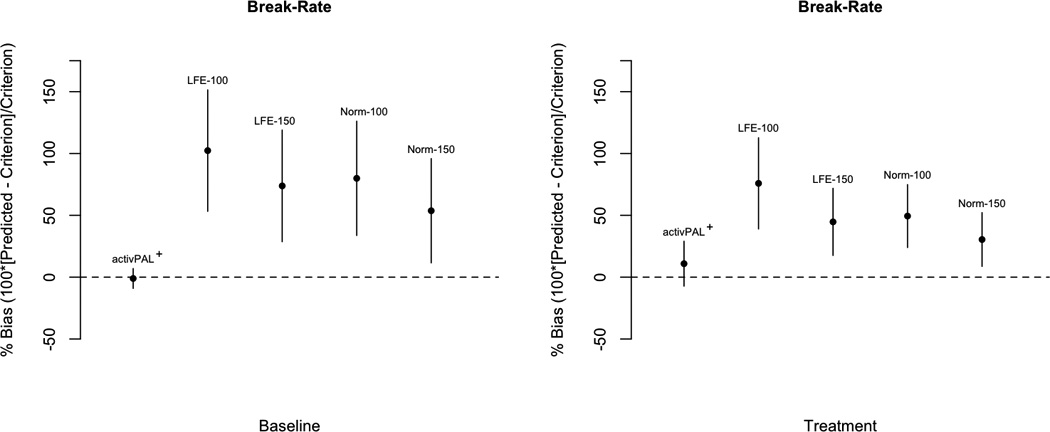

For aim two we examined the accuracy and precision of the ActiGraph GT3X and activPAL for determining absolute number of breaks and break-rate. In Table 2 the percent bias (95% CI) for each method’s estimate of absolute number of breaks and break-rate is reported. The activPAL accurately and precisely estimated absolute number of breaks in the baseline (bias: 0.3% [−7.0–7.7]) and treatment conditions (bias: 10.9% [−6.8–28.6]), while all AG-LFE and AG-Norm cut-points significantly overestimated breaks in both conditions. In general, the accuracy and precision of the AG-LFE and AG-Norm improved as the sedentary cut-point increased. Additionally, for a given cut-point, AG-Norm was always more accurate and precise than AG-LFE. Both AG-LFE and AG-Norm overestimated absolute number of breaks to a larger degree in the treatment condition compared with the baseline condition.

Table 2.

Percent bias (95% CI) of monitor estimates and correlations of monitor estimates with direct observation

| n | Sedentary Time | Absolute Number of Breaks | Break-Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Bias | Correlation | % Bias | Correlation | % Bias | Correlation | ||

| Baseline | |||||||

| activPAL | 13 | 1.6 (−0.1–3.4)+ | 0.99* | 0.3 (−7.0–7.7)+ | 0.97* | −1.0 (−9.1–7.0)+ | 0.97* |

| AG-LFE-100 | 12 | 5.6 (−5.2–16.4)+ | 0.52 | 110.7 (60.2–161.3) | 0.86* | 102.3 (53.2–151.4) | 0.87* |

| AG-LFE-150 | 12 | 12.2 (1.6–22.7) | 0.57* | 91.4 (44.6–138.2) | 0.90* | 73.8 (28.7–118.9) | 0.89* |

| AG-Norm-100 | 11 | 12.1 (1.3–22.9) | 0.58* | 98.6 (50.6–146.6) | 0.92* | 79.9 (33.7–126.1) | 0.93* |

| AG-Norm-150 | 11 | 17.8 (6.9–28.8) | 0.63* | 77.8 (33.4–122.2) | 0.92* | 53.7 (11.6–95.8) | 0.93* |

| Treatment | |||||||

| activPAL | 13 | −0.1(−0.9–1.1)+ | 1.00* | 10.9 (−6.8–28.6)+ | 0.81* | 10.9 (−7.2–29.1)+ | 0.90* |

| AG-LFE-100 | 12 | 35.9 (12.5–59.4) | 0.88* | 133.3 (69.4–197.2) | 0.64* | 75.8 (39.0–112.7) | 0.88* |

| AG-LFE-150 | 12 | 48.6 (21.6–75.6) | 0.86* | 110.6(54.5–166.6) | 0.70* | 44.7 (17.6–71.8) | 0.89* |

| AG-Norm-100 | 11 | 40.7 (20.3–61.0) | 0.84* | 112.1 (52.9–171.3) | 0.65* | 49.4 (24.0–74.8) | 0.82* |

| AG-Norm-150 | 11 | 50.7 (26.9–74.5) | 0.79* | 98.1 (42.0–154.1) | 0.66* | 30.4 (8.7–52.2) | 0.85* |

Estimate not significantly different from direct observation. The smaller the bias and the narrower the CI width, the more accurate and precise the prediction.

Significantly correlated with direct observation.

The activPAL accurately estimated break-rate in the baseline and treatment conditions, while no AG-LFE, or AG-Norm cut-point accurately estimated break-rate in either condition. The activPAL bias and CI widths were the smallest in both conditions (baseline condition bias: −1.0% [−9.1–7.0], treatment condition bias: 10.9% [−7.2–29.1]).

In both conditions, the AG-LFE and AG-Norm tended to overestimate break-rate, and accuracy (bias) and precision (CI width) improved as the sedentary cut-point increased. For each cut-point the AG-Norm had a smaller bias and narrower CI width compared with the AG-LFE. For each cut-point, both the AG-LFE and AG-Norm were more accurate and precise in the treatment condition compared with baseline.

Figure 1 illustrates the percent bias for each estimate of absolute number of breaks (top panel) and break-rate (bottom panel). The horizontal axis represents the truth relative to direct observation, thus the closer the bias falls to the horizontal axis, the more accurate the estimate. The error bars are 95% CI of the bias and illustrate the precision of the estimate. If the error bars cross the horizontal axis, the estimate from the monitor is not significantly different than the criterion DO measure. It is important to note that CI’s are dependent on sample size. Although for aim two our sample sizes were different for each monitor (activPAL = 13, AG-LFE = 12 and AG-Norm = 11), these differences did not influence the relative precision of each tool nor any conclusions about the significance of the estimates (data not shown). This was determined by performing the analyses on identical sample sizes (N=11) (e.g. if AG-Norm data was missing for an observation, AG-LFE and activPAL data were also eliminated). Since our conclusions did not change when removed, we chose to keep these data in our analyses.

Figure 1.

Bias for activPAL and ActiGraph estimates of absolute number of breaks (top panel) and break-rate (bottom panel). Error bars = 95% CI of the bias. * Not significantly different from direct observation. activPAL: n=13, AG-LFE: n=12, AG-Norm: n=11.

In Table 2, we also report the correlation between estimated metrics and direct observation. For all monitors, there were significant correlations between direct observation and estimated sedentary time (except AG-LFE-100), absolute number of breaks and break-rate (range: 0.56–0.99). For each metric, correlations were the highest for estimates from the activPAL and correlations for AG-Norm estimates tended to be higher than those for AG-LFE estimates.

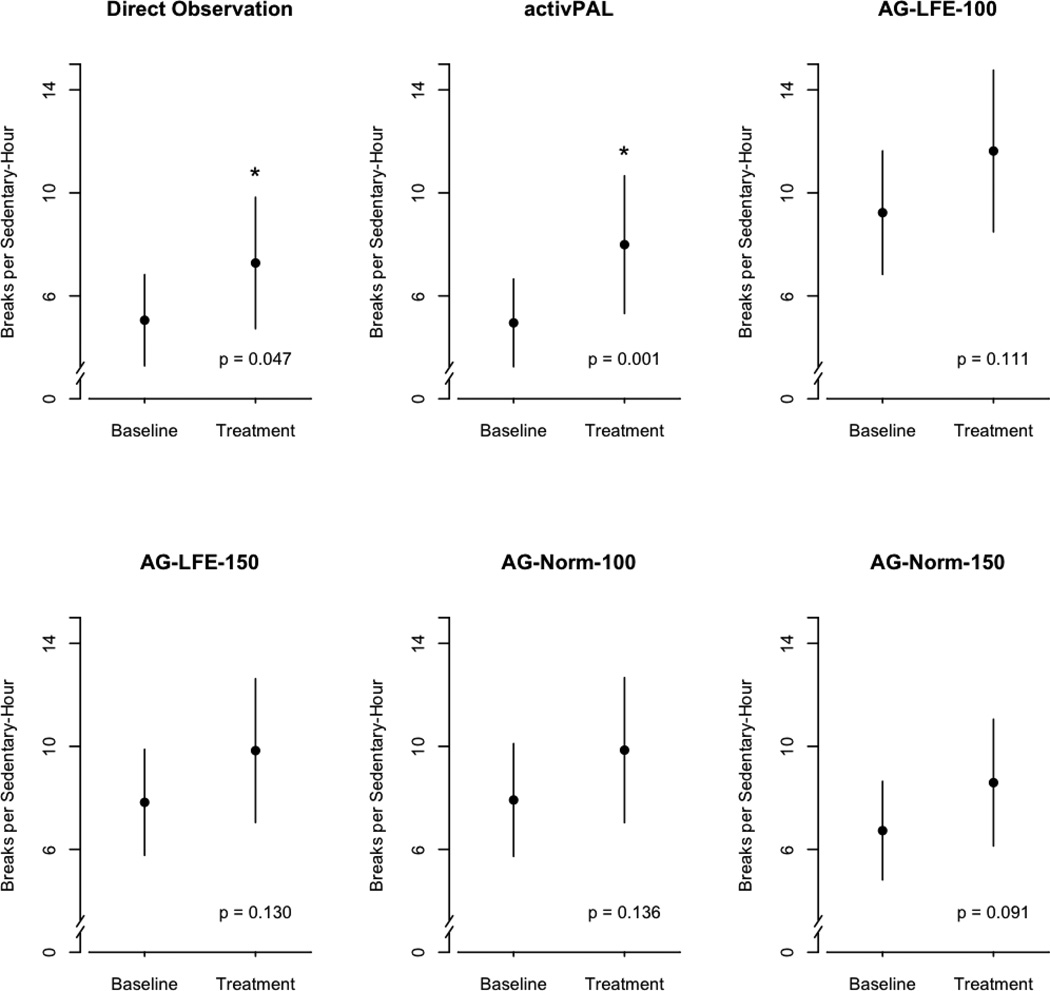

For aim three we evaluated the ActiGraph GT3X and activPAL’s sensitivity to detect the effects of an intervention to reduce and break-up sedentary time. Since absolute number of breaks did not change between conditions, we performed the sensitivity analysis only using break-rate as the response. Figure 2 illustrates the sensitivity of each method to detect the effects of the intervention on break-rate. Agreeing with the direct observation results, the activPAL detected the effects of the intervention on break-rate (p = 0.001). Results from AG-LFE and AG-Norm were indeterminate (range: p=0.091 (AG-Norm-150) to p=0.136 (AG-Norm-100).

Figure 2.

Mean estimates of break-rate per condition. Error bars = 95% CI and p-value is from the likelihood ratio testing. The lower the p-value, the more sensitive the measurement method was to the intervention. * Measurement method detected the intervention. activPAL: n=11, AG-LFE: n=11, AG-Norm: n=11.

Discussion

The epidemiologic evidence linking sedentary time to poor health continues to expand (28). The use of wearable monitors to objectively measure behavior for days to weeks at a time has allowed researchers to investigate the specific role of breaks from sedentary time. The current study contributed to this literature in three ways. First, we demonstrated the utility of a measure of sedentary behavior, the “break-rate.” Even with a modest sample size, this study demonstrated break-rate is sensitive to an intervention to reduce and break-up sedentary time. An existing measure of sedentary behavior, absolute number of breaks was not sensitive to the intervention in this study. Second, we found that the activPAL estimates of absolute number of breaks and break-rate agreed with direct observation to a large extent. The activPAL estimates were also relatively precise. This suggests the differences between the activPAL estimates and direct observation may not be practically different for many applications. Third, we found a statistically significant difference between the ActiGraph GT3X estimates of absolute number of breaks and break-rate compared with direct observation. This bias was statistically significant despite our modest sample size and the relatively low precision of the ActiGraph measures of those statistics. Whether the bias is practically significant (or whether the correlation between the ActiGraph estimates and direct observation is large enough) will depend on the application. Additionally, in our study sample the ActiGraph GT3X was not sensitive enough to detect the intervention.

Table 1 provides a summary of how participants changed behavior between the baseline and treatment conditions according to the criterion DO. Interestingly, when individuals were encouraged to reduce and break-up their sedentary time, total sedentary time decreased, but absolute number of breaks did not change significantly (baseline: 30.9 (22.2–39.6), treatment: 27.8 (20.5–35.1) (mean [95% CI]). It is important to note that when less time is spent being sedentary there are fewer “opportunities” to take breaks and vice versa. This has implications for how we interpret change within individuals and differences between groups in intervention and observational studies, respectively. It is yet to be determined how this relationship affects health, but these results illustrate the advantages of expressing breaks as a rate.

The descriptive data reported in Table 1 are important because based on the criterion DO measure, components of sedentary behavior clearly changed, but this change was not detected when absolute number of breaks was used to evaluate sedentary behavior. To truly understand the relationship between behavior and disease, it may be desirable to accurately quantify as many of these behaviors as possible. However, we are unaware of an intervention or observational study that has obtained this level of measurement detail.

Metrics not sensitive to total sedentary time are difficult to interpret and translate into meaningful information. Healy and colleagues were the first to introduce the idea that how sedentary time is accumulated may influence health, reporting a beneficial association between absolute number of breaks and metabolic risk (15). Although appropriate to establish the independent effect of breaks from sedentary time, it is difficult to relate these data to real-world applications. Notably, Healy et al. (15) recognize the challenges in expressing breaks from sedentary time as an absolute number, and suggest that future research examine the utility of expressing breaks as a rate of sedentary time. However, using a composite measure such as break-rate also has limitations. Change in break-rate will indicate sedentary behavior has changed, but this metric will provide no indication if the change was in total amount of sedentary time, how sedentary time is broken up, or both. When we measure total sedentary time and number of breaks independently, we can use statistical adjustment to evaluate the independent effects. Break-rate cannot be statistically adjusted for as this would result in variables being entered in the model twice.

The results from this study further support the use of the activPAL to measure and characterize different components of sedentary behavior. The activPAL was accurate and precise for estimating absolute number of breaks and break-rate in both the baseline and treatment conditions. It was also sensitive to the effects of an intervention on the break-rate. Previous studies indicate the activPAL is a valid tool to differentiate posture and estimate steps in both laboratory and free-living settings (10, 11, 18, 21, 26) and to estimate sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit transitions in a laboratory (11). Our results expand on this body of literature by providing free-living evidence that the activPAL is a valid tool to identify the number of transitions between sitting and standing, and it can accurately express this number as a rate per sedentary hour.

Unlike the activPAL, no AG-LFE or AG-Norm cut-point accurately identified breaks (bias = 77.8% (AG-Norm-150) to 133.3% (AG-LFE-100)) nor break-rate (bias = 30.4% (AG-Norm-150) to 102.3 % (AG-LFE-100) (Figure 1 and Table 2). Moreover, AG-Norm-100, the cut-point previously used by Healy and colleagues to identify breaks from sedentary time (13, 15), overestimated absolute number of breaks 98.6% at baseline and 112.1% during the treatment condition.

In addition to absolute number of breaks and break-rate, Table 2 also reports the percent bias of each monitor estimate of total sedentary time. Because break-rate is a ratio of breaks per sedentary hour we present these data to interpret the results for break-rate. Three observations should be noted regarding the inaccuracies of the AG-LFE and AG-Norm cut-points that will help to interpret break-rate results: 1) as the sedentary cut-point increased, overestimation of total sedentary time increased, 2) as the sedentary cut-point increased, overestimation of absolute number of breaks decreased and 3) overestimates of both total sedentary time and absolute number of breaks are larger in the treatment condition. These observations are consistent with previous results (18). Specifically, as the cut-point increases, there is more “opportunity” for a given minute to be classified as sedentary; simultaneously, it is more “difficult” to achieve a break when the threshold increases. A detailed interpretation of the validity of the activPAL and ActiGraph in estimating total sedentary time is presented by Kozey-Keadle et al (18).

The activPAL accurately and precisely at estimated all metrics of sedentary behavior in both conditions, while both the AG-LFE and AG-Norm were considerably less accurate at estimating total sedentary time and the absolute number of breaks in the treatment condition. The mean percent bias for all AG-LFE and AG-Norm estimates of total sedentary time at baseline was 11.9%, compared with 44.0% during the treatment condition. The mean percent bias for all AG-LFE and AG-Norm estimates of absolute number of breaks at baseline was 94.6%, compared with 113.5% during the treatment condition. These results indicate the accuracy of AG-LFE and AG-Norm may be influenced by wearer behavior. ActiGraph output is similar for standing still and sedentary activities and thus it is possible the ActiGraph also measures “breaks from standing”. As a result, the observed differences are likely explained by increases in standing time during the treatment condition (Table 1), which subsequently increased the likelihood the ActiGraph would misclassify standing time as sedentary time. These data are important because if the ActiGraph consistently overestimates breaks in individuals who sit less, then the improved cardio-metabolic profile associated with increased breaks (13, 15) may actually be due to individuals sitting less and not taking more breaks from sitting.

Additionally, it is reasonable to assume the more active a group, the more likely it is that the range of activity types performed will increase. It is likely that the precision of most accelerometer-based measurement tools will decrease as participants increase the range of activity types performed. This is supported by many laboratory-based calibrations where measurement errors are influenced by activity type (6, 7, 19, 25). Although the current study was not specifically designed to address the question of varying activity type, our results suggest this will minimally affect the accuracy and precision of the activPAL on a group level, but may influence ActiGraph estimates. More research is needed to fully understand how specific activity types influence the accuracy and precision of the activPAL and ActiGraph.

Sensitivity of the activPAL and ActiGraph GT3X to an intervention to reduce and break up sedentary time

The precision of wearable monitors has implications for how well it can detect change between conditions. In both conditions, the activPAL produced the most precise estimates of break-rate (Figure 1). Not surprisingly, it also was the only predictor that detected the effects of the intervention in this study (Figure 2). These results agreed with direct observation. The bias of a prediction method does not impact its ability to detection of change. In a repeated measures analysis the biases cancel each other when the difference is within the individual. For example, even if a tool is inaccurate (biased) it can still be precise if the bias for each individual is similar (e.g. the tool overestimates by 30% for each participant). Practically, this means when used in an intervention, the activPAL will be capable of detecting a true increase or decrease in break-rate. Conversely, the AG-LFE and AG-Norm did not detect the effects of the intervention on break-rate.

This is the first study to validate the performance of activity monitors to measure and detect changes in breaks from sedentary time. An important strength of this study is that it was performed under free-living conditions and sedentary time and breaks from sedentary time were measured using direct observation as the criterion measure. Participants were observed for approximately 10 consecutive hours per observation, in their natural environment. By using a custom designed direct observation system (Noldus Information Technology; Netherlands), we acquired 15,089 minutes of DO data synchronized with recordings from multiple activity monitors. Because these data were collected in participant’s natural environment over an extended period of time, we were also able to capture sedentary behavior in a wide range of settings and contexts.

We also assessed performance under two free-living conditions representative of behavior pre and post a sedentary behavior intervention. This is important for two reasons. First, Kozey-Keadle et al (2010) reported that activity monitor accuracy may be influenced by wearer behavior (18) and second, we assessed if the activity monitors were sensitive to change. Thus we provide practical information that can be easily translated to natural settings.

This study also has several limitations. First, our sample was relatively young, lean and met the physical activity guidelines. We do not know how the activPAL and ActiGraph GT3X will perform for sedentary, overweight populations, particularly since the accuracy of the ActiGraph appears to be influenced by total sedentary time. Second, participants were only monitored for one day. This may have affected how participants changed their behavior from baseline to the treatment condition. It is not known how the monitors will perform when worn for longer periods of time or if the monitors will be sensitive to changes in habitual activity. Third, we tested the performance of the ActiGraph using output in one-second epochs from the vertical axis only. We chose to assess performance in this way because previous studies (15, 16) identified sedentary time and breaks in a similar manner. However future studies should assess ActiGraph performance using additional epochs and axes to detect sedentary time. Future studies should also test the utility of the ActiGraph inclinometer to detect transitions between seated and standing postures.

This study provides further evidence the activPAL is a valid device for measuring total sedentary time (18) and our results provide the first evidence that the activPAL can identify specific features of free-living sedentary behavior. Relative to the criterion measure of direct observation, the activPAL accurately and precisely estimated sedentary time, absolute number of breaks and break-rate. It also agreed with direct observation and was sensitive enough to detect the effects of an intervention to reduce and break up sedentary time in free-living conditions.

This study also illustrates the difficulty in measuring sedentary behavior using a single, hip mounted accelerometer. In general, the ActiGraph GT3X did not accurately estimate total sedentary time, absolute number of breaks or break-rate. Its accuracy in estimating these metrics was dependent on 1) the cut-point used to distinguish sedentary time, 2) the filter setting and 3) the behavior of the sample population. Additionally, the ActiGraph GT3X vertical axis did not detect the effects of an intervention to reduce and break up sedentary time regardless of the sedentary cut-point and filter setting used.

By describing and validating measures sensitive to features of sedentary behavior this study informs future investigation into how sedentary behavior influences health. When participants were given a simple recommendation relevant to and realistic for an increasingly sedentary public, break-rate was sensitive to the behavioral changes observed. This is a relatively new field of research and more evidence is needed to determine the specific features of sedentary behavior (e.g., total sedentary time, breaks per day, break-rate) that are important for health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Funded by: NHLBI 1RC1 HL099557-01. The results of this study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants who volunteered for this study and all graduate and undergraduate students who helped with data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Kate Lyden: No Conflict of Interest

Sarah Kozey-Keadle: No Conflict of Interest

John Staudenmayer: No Conflict of Interest

Patty Freedson is on the Scientific Advisory Board for ActiGraph, which manufactures one of the monitors used in this study.

References

- 1.Bey L, Hamilton MT. Suppression of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity during physical inactivity: amolecular reason to maintain daily low-intensity activity. J Physiol. 2003;551(Pt 2):673–682. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chastin SF, Baker K, Jones D, Burn D, Granat MH, Rochester L. The pattern of habitual sedentary behavior is different in advanced Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(13):2114–2120. doi: 10.1002/mds.23146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chastin SF, Granat MH. Methods for objective measure, quantification and analysis of sedentary behaviour and inactivity. Gait Posture. 2010;31(1):82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Services USDoHaH, editor. Committee PAGA. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Washington, DC: 2008. p. D-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig CLMA, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouter SE, Churilla JR, Bassett DR., Jr Estimating energy expenditure using accelerometers. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crouter SE, Clowers K, Bassett DR., Jr A Novel Method for Using Accelerometer Data to Predict Energy Expenditure. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:1324–1331. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00818.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekelund U, Brage S, Besson H, Sharp S, Wareham NJ. Time Spent Being Sedentary and Weight Gain in Healthy Adults: Reverse or Bidirectional Causality. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:612–617. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Application Inc. Accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godfrey ACK, Lyons GM. Comparison of the performance of the activpal professional physical activity logger to a discrete accelerometer-based activity monitor. Med Engineering & Physics. 2007;29:930–934. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant PM, Ryan CG, Tigbe WW, Granat MH. The validation of a novel activity monitor in the measurement of posture and motion during everyday activities. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(12):992–997. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2007;56(11):2655–2667. doi: 10.2337/db07-0882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healy GN, Clark BK, Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Brown WJ, Matthews CE. Measurement of adults' sedentary time in population-based studies. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. Objevtively Measured Light-Intensity Activity Physical Activity Is Independently Associated with 2-h Plasma Glucose. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1384–1389. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Cerin E, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. Break in Sedentary Time. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):661–666. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EA, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003-06. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):590–597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmerhorst HJ, Wijndaele K, Brage S, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U. Objectively measured sedentary time may predict insulin resistance independent of moderate-and vigorous-intensity physical activity. Diabetes. 2009;58(8):1776–1779. doi: 10.2337/db08-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozey-Keadle S, Libertine A, Lyden K, Staudenmayer J, Freedson PS. Validation of wearable monitors for assessing sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1561–1567. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820ce174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyden K, Kozey SL, Staudenmeyer JW, Freedson PS. A comprehensive evaluation of commonly used accelerometer energy expenditure and MET prediction equations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(2):187–201. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch BM, Dunstan DW, Winkler E, Healy GN, Eakin E, Owen N. Objectively assessed physical activity, sedentary time and waist circumference among prostate cancer survivors: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–2006) Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20(4):514–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddocks MPA, Skipper L, Wilcock A. Validity of three accelerometers during treadmill walking and motor vehicle travel. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:606–608. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.051128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthew CE. Calibration of Accelerometer Output for Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2005;37(Supplement):S512–S522. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185659.11982.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, Pate RR, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen N, Healy GN, Matthew CE, Dunstan DW. Too Much Sitting: The Population Health Science of Sedenatry Behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Review. 2010;38(3):105–113. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothney MP, Schaefer EV, Neumann MM, Choi L, Chen KY. Validity of physical activity intensity predictions by ActiGraph, Actical, and RT3 accelerometers. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(8):1946–1952. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan CGGP, Tigbe WW, Granat MH. The validity and reliability of a novel activity monitor as a measure of walking. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:779–784. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.027276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Team RDC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2009. [2008]; Available from: http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW. Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zderic TW, Hamilton MT. Physical Inacivity Amplifies the Sensitivity of Skeletal Muscle to the Lipid-Induced Downregulation of Lipoprotein Lipase Activity. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:249–257. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00925.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]