Abstract

BACKGROUND

Many patients nationwide change their primary care physician (PCP) when internal medicine (IM) residents graduate. Few studies have examined this handoff.

OBJECTIVE

To assess patient outcomes and resident perspectives after the year-end continuity clinic handoff

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort

PARTICIPANTS

Patients who underwent a year-end clinic handoff in July 2010 and a comparison group of all other resident clinic patients from 2009–2011. PGY2 IM residents surveyed from 2010–2011.

MEASUREMENTS

Percent of high-risk patients after the clinic handoff scheduled for an appointment, who saw their assigned PCP, lost to follow-up, or had an acute visit (ED or hospitalization). Perceptions of PGY2 IM residents surveyed after receiving a clinic handoff.

RESULTS

Thirty graduating residents identified 258 high-risk patients. While nearly all patients (97 %) were scheduled, 29 % missed or cancelled their first new PCP visit. Only 44 % of patients saw the correct PCP and six months later, one-fifth were lost to follow-up. Patients not seen by a new PCP after the handoff were less likely to have appropriate follow-up for pending tests (0 % vs. 63 %, P < 0.001). A higher mean no show rate (NSR) was observed among patients who missed their first new PCP visit (22 % vs. 16 % NSR, p < 0.001) and those lost to follow-up (21 % vs. 17 % NSR, p = 0.019). While 47 % of residents worried about missing important data during the handoff, 47 % reported that they do not perceive patients as “theirs” until they are seen by them in clinic.

CONCLUSIONS

While most patients were scheduled for appointments after a clinic handoff, many did not see the correct resident and one-fifth were lost to follow-up. Patients who miss appointments are especially at risk of poor clinic handoff outcomes. Future efforts should improve patient attendance to their first new PCP visit and increase PCP ownership.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2100-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: outpatient handoffs, signout, resident continuity clinic, year-end transfer, transitions of care

BACKGROUND

It is estimated annually between 640,000 and 1.92 million patients experience a transfer of primary care when residents graduate and handoff their clinic patients.1 Although the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires that residents are ‘competent’ in handoff communications and programs monitor handoff safety, most training focuses on inpatient handoffs.2 Internal medicine (IM) year-end continuity clinic handoffs have received little attention.3

The year-end clinic handoff may pose several risks to patients who simultaneously face the end of a treatment relationship and a handoff to a less experienced resident, which may delay care.1 Ownership may be problematic as physicians assume responsibility for patients they have not met. Because greater continuity of primary care is associated with improved patient outcomes, year-end clinic handoffs may also be risky for patients due to discontinuity of care.4 One recent study demonstrated that after a clinic handoff, patients often do not have a follow-up appointment, do not return to re-establish care and have tests that are not followed-up.5

Unfortunately, little is known about how to improve year-end clinic handoffs. Personally informing patients of the handoff is the major predictor of patient satisfaction.6,7 In a psychiatry residency, a multifaceted intervention increased the number of patients seen one month after the clinic handoff, and improved patient outcomes.8,9 Research from inpatient handoffs suggests using structured templates to promote standardization of content, identifying the sickest patients, and confirming professional responsibility can be helpful.10–12

However, clinic handoffs pose a unique challenge, as it is common to transfer a panel of hundreds of patients. As it is not possible to discuss all patients, a reasonable first step is to identify those patients that are at highest risk of poor outcomes. In a psychiatry clinic handoff, residents focused on “acute patients” requiring follow-up within four weeks of the handoff, defined by criteria for suicide risk and potential for destabilization with the end of a treatment relationship.9 In one study, IM residents focused on patients requiring follow-up within one year, which may not be selective enough given the chronic illness burden of resident clinic patients.5,13,14 Given the heterogeneity of IM clinic patients, residents likely rely on physician intuition to choose whom to focus on during clinic handoffs.15-18 Therefore, it is important to understand how residents prioritize patients for clinic handoffs when communicating to the new resident primary care provider (PCP). Characterizing these patients and their outcomes can help inform interventions to improve resident clinic handoffs.

Our study aims were to characterize patients identified by residents as “high-risk” during the handoff; to understand the scheduling process, and outcomes related to test follow-up and acute care use for these patients after the handoff. Lastly, we sought to characterize perceptions of residents who receive clinic handoffs.

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study from June 2010 to January 2011 of all resident clinic patients listed on a sign-out by graduating residents during a year-end clinic handoff at a single, academic IM resident continuity clinic. Approximately 30 IM residents per class have clinic at this site, spending half-days in clinic for the duration of their residency supervised by faculty preceptors consistent with ACGME regulations.2 There are two licensed practical nurses dedicated to residents’ patients. This study was granted an institutional review board exemption.

Baseline Clinic Handoff Process

Our graduating residents select one or two rising PGY2 residents to takeover their clinic panel. Because our interns start clinic in August and build up appointments slowly, departing residents transfer their clinics to rising PGY2’s who have more appointments than interns and to avoid overwhelming the interns. Furthermore, rising PGY2’s are also present when PGY3’s are departing.

Residents are not assigned a primary faculty preceptor, but work with a core group of faculty. To facilitate mentorship outside of clinic, residents are assigned to practice groups with approximately three faculty. Group residents share the same nurse and after-hours phone call but do not share patients. To preserve continuity with nurses, residents are encouraged to select a PGY2 from their group. PGY3 panels average roughly 100 patients by graduation. Faculty are not formally involved in the clinic handoff.

Prior to 2010, residents were asked to sign-out pertinent patient information to the new resident. This was not enforced and no structured template was provided. Patients received a letter notifying them of the transition and were scheduled with the new PCP depending on availability. Afterwards, paperwork and clinical needs were directed to the new PCP.

Implementing a Structured Clinic Handoff Sign-out

In June 2010, departing residents were asked to complete a standardized sign-out worksheet. Given the volume of patient panels, residents were not asked to record every patient on the sign-out. Instead we asked residents to focus on patients who would require more attention during the handoff. Thus residents were asked to use their clinical judgment to list patients they believed were “high-risk” during the handoff using their knowledge of their patient panels. Residents were not given formal guidance on who to select but attended a meeting about the handoff with the associate program director (JO). Graduating residents listed reasoning for high-risk designation, target follow-up date, and pending tests for high-risk and other patients. During a designated handoff meeting, departing residents discussed patients with the PGY2’s inheriting their clinic. Patients received letters notifying them of the transition. Resident clinic schedules for the two months after the handoff (July and August) were available in May. When possible, patients received appointments at their last visit or were placed on a wait list. In mid-June, sign-outs were sent to clinic coordinators to facilitate necessary patient scheduling using the standard scheduling infrastructure.

Data Collection

Sign-outs were collected to record the number of high-risk patients per sign-out, target follow-up dates and any pending tests listed. Constant comparative method was used to categorize reasons for high-risk designation. Six months later, basic demographics including age, gender, ethnicity, and the following chronic conditions: diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, COPD, and asthma, were obtained for all high-risk patients from the Eclipsys database, which contained inpatient and outpatient encounter information and attending and examining physician for all medical center encounters.

Six months post-handoff, charts of high-risk patients were reviewed to determine if and when patients were scheduled, if they saw the correct new PCP who received the handoff, the number of PCP’s in five years, the number of PCP visits patients missed in the past year prior to the handoff (June 2009–2010), and the no show rate to all outpatient visits at the medical center reported in the electronic medical record (EMR) from the date of analysis (Jan 2011) until January 2007. Data from the Eclipsys database and charts were also reviewed to examine ED visits and hospitalizations during the three-month post-handoff period (July 2010–October 2010). ED visits during a different three-month period were also reviewed for comparison (November 2010–January 2011). We also examined associations between follow-up, patient factors (no show rates), and outcomes (ED visits or hospitalizations) in the three-month handoff period.

Characterization of “High-Risk” Patients

Basic demographic data (age, gender, ethnicity, chronic conditions) and acute visits (ED visits, hospitalizations and hospital days) were extracted from the Eclipsys database for all other resident clinic patients (defined as any patient seen by a resident for two or more visits during a two-year period from January 2009–2011). This data was compared to high-risk patient data from the same period to characterize high-risk patients.

Test Follow-up

We reviewed charts of high-risk and other patients with pending tests listed on sign-outs. These were tests the graduating resident was unable to follow-up because of their departure. Charts were reviewed to see if tests occurred, were followed-up by the new PCP and if the result was abnormal. Associations between follow-up of tests and PCP visits after the handoff were examined.

Resident Perspective Data

Based on information gained from three focus groups with PGY2’s, a 14-item survey was drafted regarding perceptions of the handoff (available online). Four months post-handoff, PGY2’s were surveyed anonymously regarding the handoff process, satisfaction, missed information and any near misses/adverse events. Perceptions were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of the high-risk patient sample including basic demographics, scheduling outcomes, patient factors and handoff outcomes were examined using STATA 11.0 (College Station, TX). Chi square, Fisher’s exact, and t-tests were utilized as appropriate to compare high-risk patients to all other resident patients and test associations between patient-specific factors (no show rate) and handoff-related outcomes (missed PCP visits or acute visits) among high-risk patients. Descriptive statistics of resident survey responses were examined and data was dichotomized for analysis (“agree” was defined as a Likert response of agree or strongly agree).

Results

Twenty-five of 30 graduating IM residents (83 %) provided sign-outs listing 258 high-risk clinic patients. The average number of high-risk patients per resident was 10 (range 4–25). The majority of the patients were female (65.5 %) and African-American (80 %) with a mean age of 61 (range 27–95) (Table 1). On average, patients were transitioning to their 3rd PCP in 5 years (range 2–6). Patients were most likely deemed high-risk due to complexity (60 %, 154/258), new diagnoses (28 %, 73/258), psychiatric diagnoses (18 %, 47/258), difficult social situation (14 %, 35/258), and non-adherence (12 %, 31/258).

Table 1.

Characteristics and Acute Care Visits of High-Risk Patients in Comparison to All Other Resident Clinic Patients

| Characteristic | High-Risk Patients, n = 258 (%) | Other resident patients, n = 5875 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age ± SD | 61.3 ± 13.5 | 57.3 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Female | 169 (65.5) | 3,914 (66.6) | 0.710 |

| African-American | 206 (80) | 4103 (70) | 0.001 |

| Mean Number of Co-morbidities* ± SD | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 53 (21) | 826 (14) | 0.004 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 86 (33) | 812 (14) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 67 (26) | 624 (11) | <0.001 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 77 (30) | 960 (16) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 146 (57) | 2455 (42) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 231 (90) | 4134 (70) | <0.001 |

| Patients with an ED visit in 2 years | 150 (58) | 2,496 (42) | <0.001 |

| Patients hospitalized in 2 years | 96 (37) | 1338 (23) | <0.001 |

| Mean inpatient days in 2 years ± SD | 4.4 ± 10.5 | 2.4 ± 8.8 | <0.001 |

*Co-morbidity measurement includes the following chronic conditions (asthma, CAD, CHF, COPD, diabetes, and hypertension)

High-Risk Patient Characterization

Using the Eclipsys database, 5875 patients were identified who had seen a resident for two or more visits during January 2009 – January 2011. In comparison to other resident patients, resident-identified high-risk patients had more co-morbidities, were more likely to be seen in the ED or hospital and spent more days in the hospital over a two-year period (Table 1).

Scheduling Outcomes

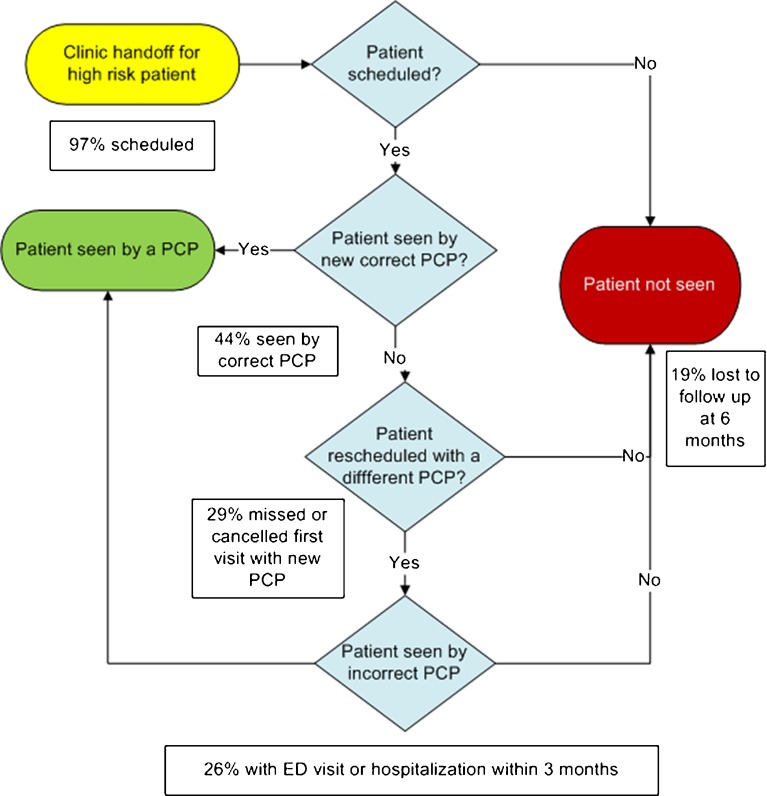

Nearly all patients (97 %, 250/258) were scheduled for follow-up appointments (Fig. 1). Ultimately, 44 % (113/258) of patients saw the correct PCP. The average time between seeing the old and new PCP was 110 days (range 11–350). Six months later, one-fifth (19 %, 50/258) of patients had not been seen. Seeing the correct PCP was associated with less time between visits with the old and new PCP (95 vs. 128 days, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Year-end clinic handoff process map and handoff outcomes. This figure represents the process map for potential patient outcomes during the year-end clinic handoff. Handoff outcomes for the high-risk patients are presented in the text boxes as percent of patients (n = 258) with the specified outcome.

Overall 29 % (75/258) of patients no showed or cancelled their first visit with their new PCP. In addition, 42 % (109/258) of patients missed a PCP visit in the past year. The mean EMR no show rate (NSR) to all outpatient visits for high-risk patients was 17.7 % (range 0 % to 64 %). A significantly higher mean NSR was noted among patients who missed their first visit with their new PCP (22 % vs. 16 % mean NSR, p < 0.001) and those lost to follow-up (21 % vs. 17 % NSR, p = 0.019).

Acute Visits

Overall, 26 % (68/258) of the high-risk patients visited the ED or were hospitalized during the three-month post-handoff period (July-October 2010) and 20 % (51/258) visited the ED. Although not statistically different, ED visit rates post-handoff were higher than a different delayed three-month control period (November 2010-January 2011) when 15 % (39/258) of high-risk patients visited the ED (p = 0.164). Getting scheduled, timing of follow-up, missing the first PCP visit, seeing the correct PCP or being lost to follow-up was not associated with acute visits after the handoff. High-risk patients who missed at least one PCP appointment in the last year were more likely to have had an acute visit (33 % vs. 22 %, p = 0.038).

Test Follow-up

On 25 sign-outs, 18 items were identified for 17 high-risk patients and 30 items were identified for 27 other patients. The types of tests listed were imaging (63 %), procedures (23 %), blood tests (13 %), and specialist visits (2 %). The reasons for the tests included diagnostic (58 %), preventive (17 %), and therapeutic (2 %). Six months post-handoff, 54 % (26/48) of tests were not followed-up. Of these, 65 % (17/26) were abnormal or incomplete. Very few (4 %, 2/48) tests were followed-up before the first new PCP appointment. Patients who were not seen by a new PCP were least likely to have tests followed-up (0 % vs. 63 %, p < 0.001). There was no difference seen in test follow-up for high-risk and other patients.

Resident Perspective Data

Almost all (95 %, 19/20) PGY2’s completed surveys (Table 2). Only 16 % (3/19) of PGY2’s reported not receiving a sign-out. The majority (28 %) of handoffs took approximately 5–10 or 10–20 minutes (14 %). Most residents (74 %, 14/19) reported “most or all” patients were generally aware of the transition. Overall, 32 % thought the handoff was stressful. While 47 % of residents worried about missing important patient data, few (16 %, 3/19) reported discovering information that should have been discussed. Few (21 %, 4/19) residents reported either a near miss/adverse event or missed test. Two residents reported delayed care due to a missed test result they were not told to follow-up. One resident was notified that their new patient was admitted to another ICU shortly after the handoff. Almost half (47 %) of residents reported they do not take ownership of a patient until the first clinic visit and 74 % do not feel comfortable completing paperwork for a patient they have not met.

Table 2.

PGY2 Resident Survey Themes (n = 19, 95 % Response Rate)

| Content, n = 19 (%)* | Responsibility, n = 19 (%)* |

|---|---|

| The clinic transition is stressful 6 (32) | A patient is not mine until I see them in clinic 9 (47) |

| I am concerned about missing important data 9 (47) | I do not feel comfortable completing paperwork for a patient I have not seen in clinic 14 (74) |

| It is helpful when the patients are prepared for the transition 17 (89) | Having transfer patients see me in clinic as soon as possible is better for patient care 14 (74) |

*percent of respondents who agreed based on a 5-point Likert scale

DISCUSSION

Our study is consistent with the few existing studies of clinic handoffs that demonstrate that this process is a vulnerable time for patients.5,8,9 Our study is novel in several ways. In addition to scheduling outcomes, our study examined more distal and relevant clinic handoff outcomes, such as, being lost to follow-up, missed visits, seeing the correct PCP, and acute visits. Despite effective scheduling, many patients missed their first new PCP visit and were subsequently lost to follow-up. Patients who missed appointments were at greater risk after clinic handoffs, with more loss to follow-up, missed tests, and acute visits. This highlights the importance of considering a pattern of missed visits as a risk factor for poor clinic handoffs. Lastly, residents do not perceive a patient to be ‘theirs’ until they are seen in the clinic, highlighting the need to augment resident ownership of new patients after a clinic handoff.

Unlike prior studies, we chose not to give residents specific criteria to select patients to handoff, but instead counseled them to rely on physician intuition and knowledge of ongoing care.5,9,15–18 Using this simple strategy, residents were able to identify their patients who were sicker, used acute care more, and were likely at greatest risk during the handoff. Our study has potential to inform IM residents how to identify patients at risk during clinic handoffs. Criteria may include complexity, frequent missed visits, frequent acute visits, new diagnoses, psychiatric disease, challenging social situation or non-adherence.

It is not clear why so many patients missed their first visit with their new PCP or why they never rescheduled. Patients may have been frustrated with transitioning to another PCP or be reluctant to see a PCP with whom they have not established a personal relationship. They may have transferred their care to another institution or continued care solely with a specialist. Eliciting patient perspectives to explore this problem is critical.

Even when high-risk patients were seen, half did not see the correct resident who received the handoff. In these cases, the information conveyed during the handoff was lost. Reasons for patients to see another PCP require further investigation but may include limited availability for rescheduling with a specific resident, or patient preference (i.e. provider-gender concordance). Those who saw the correct PCP were more likely to be seen sooner. Since patients infrequently see the correct PCP, efforts to make handoff documents widely available are important for clinics with EMR’s. We now encourage residents to add sign-out items to their last clinic note to ensure information transmission even if a patient sees another PCP.

Interestingly, many residents don’t think that patients are “theirs” until they see them in clinic and aren’t comfortable completing paperwork for patients they have not met. This suggests one possible mechanism why patients who did not see a new PCP were less likely to have appropriate follow-up for pending tests. Because we only examined tests pending at the time of resident departure and not routine monitoring (i.e. HbA1c), we are likely underestimating the risks of delayed care. Future work should aim to improve resident ownership of newly transferred patients, even if they miss their visit.

This study has several limitations. While our patient demographics and clinic design are similar to other urban residency clinics,13 external validity is likely limited by our institutional practice or culture. We are uncertain how our handoff outcomes compare to a program that transfers patients to interns. It is possible they are better given the experience level and availability of PGY2‘s assuming care. Not all graduating residents turned in their sign-out or attended the handoff meeting, either due to heavy workload, vacation or early departure. To increase participation, earlier resident preparation, education, frequent reminders and tracking down missing sign-outs are imperative.

Causality is hard to demonstrate as acute visits may prompt PCP visits or cause missed PCP visits if a patient is hospitalized. This study did not account for encounters (PCP or acute) at other institutions. In addition, chart documentation may not accurately reflect study follow-up if PCP’s did not document all actions. Additionally, as we had already implemented a basic handoff protocol prior to this study, our handoff outcomes may be better than clinics without any handoff protocol. We are underpowered to detect a significant difference in ED visit rates for high-risk patients during the handoff period and a delayed period. Our control period also included influenza season, making it more difficult to detect a difference.

Finally, high-risk patients in this study were identified by residents, raising concern for bias. Some high-risk patients may have been excluded, leading to an underestimation of handoff risk. We also could not examine handoff outcomes for patients who were not high-risk for comparison to examine their risks. More objective identification of high-risk patients is worth future investigation.

This study raises important implications for improving clinic handoffs in residency programs. Rescheduling and tracking down those who miss visits is important not only to advance care, but also to ensure that pending tests receive appropriate follow-up. Resident education to increase ownership of patients during the handoff is needed. Lastly, while our study focused on resident handoffs, it is important to consider other types of clinic handoffs that could place patients at risk, such as when PCP’s retire or change jobs.

In summary, year-end resident continuity clinic handoffs are a vulnerable time for high-risk patients. Improving patient attendance to the first visit with their new PCP and increasing PCP ownership is imperative. Future interventions to improve resident clinic handoffs should incorporate these findings.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 69 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Lisa Vinci MD, James Woodruff MD, Joel Roth, Sara Bares MD, Katherine Thompson MD, Lynda Hale, the University of Chicago Section of General Internal Medicine, the University of Chicago Internal Medicine Residency Program and the University of Chicago Group.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Funding

Picker Gold Challenge Grant for Residency Training.

References

- 1.Young JQ, Wachter RM. Academic year-end transfers of outpatients from outgoing to incoming residents: an unaddressed patient safety issue. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1327–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/RRC_140/140_prIndex.asp Accessed March 27, 2012.

- 3.Young JQ, Eisendrath SJ. Enhancing patient safety and resident education during the academic year-end transfer of outpatients: lessons from the suicide of a psychiatric patient. Acad Psych. 2011;35(1):54–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasson JH, Sauvigne AE, Moglelnicki RP, Frey WG, Sox CH, Gaudette C, Rockwell A. Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1984;252(17):2413–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03350170015011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caines LC, Brockmeyer DM, Tess AV, Kim H, Kriegel G, Bates CK. The revolving door of resident continuity practice. Identifying gaps in transitions of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;6(9):995–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1731-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy MJ, Kroenke K, Herbers JE., Jr When the physician leaves the patient: predictors of satisfaction with the transfer of primary care in a primary care clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(4):206–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02600256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy MJ, Herbers JE, Seidman A, Kroenke K. Improving patient satisfaction with the transfer of care, a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(5):364–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young JQ, Niehaus B, Lieu SC, O’Sullivan PS. Improving resident education and patient safety: a method to balance caseloads at academic year-end transfer. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1418–24. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab8d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young JQ, Pringle Z, Wachter RM. Improving follow-up of high risk psychiatry outpatients at resident year-end transfer. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety. 2011;37(7):300–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, Wall SD, Wachter RM. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257–266. doi: 10.1002/jhm.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora VM, Johnson J. A model for building a standardized hand-off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safety. 2006;32(11):646–655. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler D, Basaviah P, Halasyamani L, Kriplani S. Hospitalist Handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440. doi: 10.1002/jhm.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babbott SF, Beasley BW, Reddy S, Duffy FD, Nadkarni M, Holmboe ES. Ambulatory Office Organization for Internal Medicine Resident Medical Education. Acad Med. 2010;85(12):1880–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181fa46db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pincavage AT, Ratner S, Arora VM. Transfer of graduating residents' continuity practices. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27(2):145. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelson DP, Retzer E, Weidman EK, Woodruff J, Davis AM, Minsky BD, Meadow W, Hoek TL, Meltzer DO. Patient acuity rating: quantifying clinical judgment regarding inpatient stability. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(8):480–8. doi: 10.1002/jhm.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knaus WA, Harrell FE, Jr, Lynn J, Goldman L, Phillips RS, Connors AF, Jr, Dawson NV, Fulkerson WJ, Jr, Califf RM, Desbiens N, Layde P, Oye RK, Bellamy PE, Hakim RB, Wagner DP. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(3):191–203. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-3-199502010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meadow W, Frain L, Ren Y, Lee G, Soneji S, Lantos J. Serial assessment of mortality in the neonatal intensive care unit by algorithm and intuition: certainty, uncertainty, and informed consent. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):878–886. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinuff T, Adhikari NK, Cook DJ, Schünemann HJ, Griffith LE, Rocker G, Walter SD. Mortality predictions in the intensive care unit: comparing physicians with scoring systems. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):878–885. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201881.58644.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 69 kb)