ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Coordinated transitions from hospital to shelter for homeless patients may improve outcomes, yet patient-centered data to guide interventions are lacking.

OBJECTIVES

To understand patients’ experiences of transitions from hospital to a homeless shelter, and determine aspects of these experiences associated with perceived quality of these transitions.

DESIGNS

Mixed methods with a community-based participatory research approach, in partnership with personnel and clients from a homeless shelter.

PARTICIPANTS

Ninety-eight homeless individuals at a shelter who reported at least one acute care visit to an area hospital in the last year.

APPROACH

Using semi-structured interviews, we collected quantitative and qualitative data about transitions in care from the hospital to the shelter. We analyzed qualitative data using the constant comparative method to determine patients’ perspectives on the discharge experience, and we analyzed quantitative data using frequency analysis to determine factors associated with poor outcomes from patients’ perspective.

KEY RESULTS

Using qualitative analysis, we found homeless participants with a recent acute care visit perceived an overall lack of coordination between the hospital and shelter at the time of discharge. They also described how expectations of suboptimal coordination exacerbate delays in seeking care, and made three recommendations for improvement: 1) Hospital providers should consider housing a health concern; 2) Hospital and shelter providers should communicate during discharge planning; 3) Discharge planning should include safe transportation. In quantitative analysis of recent hospital experiences, 44 % of participants reported that housing status was assessed and 42 % reported that transportation was discussed. Twenty-seven percent reported discharge occurred after dark; 11 % reported staying on the streets with no shelter on the first night after discharge.

CONCLUSIONS

Homeless patients in our community perceived suboptimal coordination in transitions of care from the hospital to the shelter. These patients recommended improved assessment of housing status, communication between hospital and shelter providers, and arrangement of safe transportation to improve discharge safety and avoid discharge to the streets without shelter.

KEY WORDS: discharge care, homelessness, quality of care, community-based participatory research, mixed methods

BACKGROUND

Homelessness has been rising in the US since the 1980s, and has worsened during the economic downturn over the last five years.1,2 In 2009, an estimated 1.5 million individuals, or 1 in 200 Americans, experienced homelessness at some point during the year.3 This trend has important consequences for US hospitals, as these individuals have much higher use of acute care services such as inpatient admissions and emergency department (ED) visits.4–6 These high-use patterns likely play an important role in mediating disproportionate morbidity and early mortality for patients in this vulnerable population.7,8

The recent rise in homelessness has also created an increase in demand for shelter beds across the US, 9 and healthcare for individuals accessing these services has become an increasingly important concern. In 1996, there were approximately 40,000 homeless assistance programs nationally, providing a broad range of services including 150,000 health-related contacts per year.10 As the number of these programs specifically focused on emergency shelter or supportive housing has increased from 15,890 to 20,525 in the last 15 years, transitions between this growing “shelter system” and the healthcare system have also become increasingly common, especially for acute care. By 2010, approximately 7 % of all homeless individuals and 13 % of newly-homeless individuals seeking shelter from one of these programs were received directly from a hospital.11 These transitions are often marked by inadequate coordination of care, which may further perpetuate high rates of acute care services.12,13

Recognizing the importance of these transitions, many communities have called on hospitals to become more engaged in efforts to combat homelessness, through improvements in discharge planning and integration with local housing assistance programs.14,15 Despite these efforts, there are no data from homeless patients regarding barriers they perceive to safe and supportive transitions in care. These data are needed to integrate systems of care and implement community plans. Accordingly, we conducted a patient-centered, community-based project with two objectives: to understand patients’ experiences of transitions from hospital to a homeless shelter, and to determine aspects of these experiences associated with perceived quality of these transitions.

METHODS

Study Design

Using a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach,16,17 we created a partnership between Yale-New Haven Hospital (YNHH), the largest hospital in our community, and Columbus House, the largest homeless shelter in New Haven, Connecticut. Columbus House is a not-for-profit organization that provides emergency shelter, transitional housing, permanent supportive housing, and community outreach services.18 In addition to Columbus House, there are two smaller homeless shelters in New Haven; one serves only men19 and the other serves only women.20 YNHH is a not-for-profit teaching hospital and, like many teaching hospitals, provides a large proportion of acute care for homeless patients in the community it serves. While homelessness is a major problem for the New Haven community, rates of homelessness in New Haven are similar to many other major U.S. cities.9,21

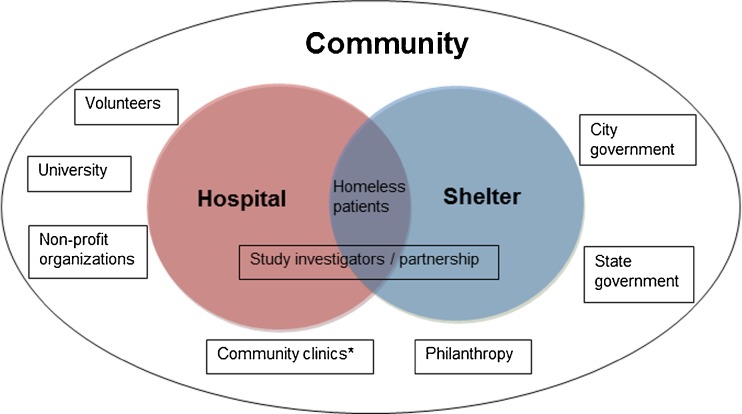

CBPR is an approach which “engages multiple stakeholders, including the public and community providers, who affect and are affected by a problem of concern”22 and “aims to combine knowledge with taking actions, including social change, to improve health.”23 Accordingly, university researchers and Columbus House personnel collaborated in all aspects of the research project, including study design, data collection, data analysis and dissemination. Further, we identified a diverse range of key stakeholders in our community for participation in our project, including: homeless individuals; city and state government officials; clinicians and administrators at our hospital; and clinicians and administrators at the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) closest to the homeless shelter. Through a series of discussions with these key stakeholders, we identified the common characteristics of the missions for each, and described how the two systems of care, hospitals and shelters, were embedded in our community (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for shelter and hospital as overlapping systems of care, and CBPR approach to study these systems as embedded in a community. *Examples include federally qualified healthcare center and veterans administration clinics.

We began our process of identifying research questions and project goals within this framework through direct engagement with these stakeholders. The primary investigator for the project (SRG) conducted extensive pre-study fieldwork by attending meetings held by the Healthcare for the Homeless group at the FQHC in New Haven, volunteering clinically each week at Columbus House in their small on-site clinic, and attending meetings of the Homeless Advisory Commission for the City of New Haven. Issues related to transitions in care from the hospital (emergency department (ED) or inpatient) to the community were the most common topics discussed in these experiences, and were clearly identified as the most important task for hospitals and healthcare providers in the City’s 10 Year Plan to End Homelessness. After further discussion with case managers, social workers, and executive staff at Columbus House, we felt that we had strong consensus that transitions in care were a top priority for providers of community-based assistance to the homeless population in New Haven. During ten individual brief interviews and one focus group with homeless individuals staying at Columbus House, we asked if they had recently accessed acute care and, if so, did they think we could improve the process. When they endorsed that improvement in this area was needed, we asked about specific topic areas we should include in our survey instrument.

As a result of our fieldwork and these discussions, we determined that our first research priority would be to generate patient-centered data about transitions in hospital care from individuals actively seeking shelter in our community. To obtain these data, we collaboratively designed a survey instrument for semi-structured interviews with individuals at Columbus House shelter.

Survey Instrument

We drafted our survey instrument and then incorporated feedback from nine individual interviews and three focus groups composed of key community stakeholders above. The survey contains 20 multiple choice questions, assessing basic demographic information, frequency of acute care visits, transportation to and from the hospital, ED, or hospital course, assessment of housing status by hospital staff, hospital discharge and disposition. We also asked two open-ended questions about acute care and transitions to explore perceptions and experiences of participants. We piloted the final survey with individuals staying at Columbus House, shelter staff, and clinicians to ensure face validity. The Yale University Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol.

Data Collection

Prior to data collection, the principal investigator trained five undergraduates from the Yale Hunger and Homelessness Action Panel24 in survey administration and data collection. After training, these student-research assistants observed several interviews performed by the principal investigator, and each was then observed performing at least one separately by the principal investigator. Research assistants recruited participants and obtained informed consent from individuals staying at Columbus House who reported they had accessed acute care at an area hospital in the past year. Specifically, we recruited individuals on eight weekday nights distributed across a two month period from April – May 2010. On each recruitment night, during the "house meeting," Columbus House staff introduced the researchers to all individuals staying at the shelter that night. We invited participation from all individuals who had sought care at an emergency room in the last 12 months and created a list of names of volunteers. We conducted interviews consecutively from this list by reading each question aloud to individual participants, and marking their responses to multiple-choice and open-ended questions. We offered these individuals (hereafter “participants”) a $20 gift card as compensation for their time and effort.

Data Analysis

Using qualitative survey data from open-ended questions, we employed the constant comparative method of qualitative data analysis.25 A multi-disciplinary team of four study authors with expertise in homelessness, hospital discharge planning, community-based participatory research, and qualitative methods independently coded the open-ended responses and met as a group to resolve discrepancies through negotiation. We developed codes iteratively, and refined them to identify conceptual segments of the data.26 The team reviewed the code structure throughout the analytic process, and revised the scope and content of codes as needed. The final code structure contains 15 codes, which we subsequently integrated into one overarching theme and three recurring themes on recommendations for improvement. Themes from this qualitative data guided our approach to analysis of quantitative data.

Using quantitative survey data from multiple choice questions, we performed frequency analysis to describe participant characteristics including age, race, gender, reported length of homelessness, setting of care (inpatient care vs. ED care only), assessment of homelessness by hospital staff, post-discharge transportation planning, time of discharge and immediate disposition. Given participant concerns that emerged from the qualitative data about safety and inability to access the shelter on the first night after discharge, we designated staying on the streets the first night after discharge as an outcome of high interest. We used SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) for quantitative analysis.

Data Presentation to Community and Feedback

Consistent with qualitative and CBPR methods, we presented data from our project, as it became available, to study participants and key stakeholders in our community (Fig. 1).16,17 From each group, we sought input on the accuracy of our findings and recommendations for implementing changes in the care of homeless individuals by area hospitals and shelters. This feedback process was critical for shaping our interpretation and presentation of data collected from study participants in the context of the community to which they belong.

RESULTS

Data from Semi-structured Survey of Homeless Participants

Ninety-eight shelter clients (82 % response rate) participated in the study. Participants reported they were 80 % (78/98) male, 42 % (39/98) black, 41 % (38/98) white, and 16 % (16/98) Hispanic. Average age was 44 years (range 18–65) and average reported length of homelessness was 2.8 years. Sixty-one percent (60/98) reported three or more total visits to an area hospital for acute care in the preceding year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total N = 98 |

|---|---|

| Age | Mean: 44 years |

| <30 | 17 (17 %) |

| 30-39 | 12 (12 %) |

| 40-49 | 37 (38 %) |

| 50-59 | 26 (27 %) |

| ≥60 | 6 (6 %) |

| Race | |

| Black | 39 (40 %) |

| White | 38 (39 %) |

| Hispanic | 15 (15 %) |

| Other | 6 (6 %) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 78 (80 %) |

| Length of homelessness | Mean: 2.8 years |

| <6 months | 28 (29 %) |

| 6-12 months | 20 (20 %) |

| 13-36 months | 28 (29 %) |

| > 36 months | 22 (22 %) |

| Setting for most recent acute care visit | |

| Inpatient admission | 52 (53 %) |

| Emergency Department | 46 (47 %) |

| Acute care visits in last 12 months* | |

| 1 | 23 (23 %) |

| 2 | 23 (23 %) |

| 3 | 11 (11 %) |

| 4-5 visits | 22 (22 %) |

| >5 visits | 17 (17 %) |

*Data missing for 2 % of participants

Using qualitative analysis, we found homeless participants perceived an overall lack of coordination between the hospital and shelter at the time of discharge. Participants described how expectation of suboptimal coordination exacerbates delays in seeking care, and made recommendations for improvement which we grouped according to three recurrent themes: 1) Hospital providers should consider housing a health concern; 2) Hospital and shelter providers should communicate during discharge planning; and 3) Discharge planning should include safe transportation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Qualitative Themes and Recommendations

| Overarching theme: Expectation of suboptimal coordination exacerbates delays in seeking care. |

| Recommendation 1: Hospital providers should consider housing a health concern. |

| Recommendation 2: Hospital and shelter providers should communicate during discharge planning. |

| Recommendation 3: Discharge planning should include safe transportation |

Expectation of Suboptimal Coordination Exacerbates Delays in Seeking Care

Given their experiences with hospital care, many participants reported they were likely to delay in seeking care. One participant explained, “I didn’t want to go wait in the ER just to find out ‘we can’t do nothing for you now…here’s an appointment to follow up later.’” Sixty percent of participants (59/98) reported that they had delayed visiting a hospital after they knew they needed care and of these, 44 % (26/59) indicated they had done so because they were concerned they would not get the care they needed. Additionally, 42 % (25/59) indicated they had delayed seeking care because they were concerned that they would not be able to find shelter for the night once discharged. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant Responses to Selected Survey Items

| Survey question | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Have you ever delayed or avoided seeking care at an area hospital? | Yes = 59 (60 %) |

| No = 39 (40 %) | |

| Why did you delay? (n = 59)* | Afraid I wouldn’t get care = 26 (44 %) |

| Afraid I wouldn’t find shelter = 25 (42 %) | |

| Afraid of what I’d learn about my health = 17 (29 %) | |

| I felt unwelcome at hospital = 11 (19 %) | |

| Afraid I might be harmed by hospital care = 6 (10 %) | |

| Did shelter staff discuss your hospital care and discharge instructions with you? | Yes = 19 (19 %) |

| No = 79 (81 %) | |

| How did you get from hospital to shelter? | 58 (59 %) walked |

| 14 (14 %) taxi | |

| 13 (13 %) public transportation (bus) | |

| 10 (10 %) got a ride | |

| 3 (3 %) not sure | |

| During your most recent hospital visit, was your housing situation discussed before you were released? | Yes = 43 (44 %) |

| No = 55 (56 %) | |

| During your most recent hospital visit, what time were you released from the hospital? | Before dark = 72 (73 %) |

| After dark = 26 (26 %) | |

| During your most recent hospital visit, where did you go immediately after you were released? | Shelter = 66 (67 %) |

| Family, friend, or other = 21 (21 %) | |

| Streets = 11 (11 %) |

*Includes only participants answering “yes” to screening question about delay in seeking care; response choice was “choose all that apply” so percentages total >100 %

Recommendation 1: Hospital Providers Should Consider Housing a Health Concern

Participants expressed that hospital staff would be better able to address health concerns of participants if they asked about housing status and other social determinants of health. One participant explained, “They [hospital providers] should be more worried about whether people have a safe place to stay beyond just physical or medical needs.” Quantitative data revealed only 44 % (43/98) of participants reported that hospital staff assessed their housing status during their most recent acute care episode (Table 3). Additionally, participants suggested that hospital providers “should ask more questions and give more referrals or resources for help,” including long-term or supportive housing options. Only 22 % (22/98) reported that hospital staff discussed long-term housing as part of discharge needs.

Recommendation 2: Hospital and Shelter Providers Should Communicate During Discharge Planning

Participants reported that even if hospital staff addressed their need for safe transportation and a safe place to stay after discharge, they still might not be able to gain access to shelter for the night. In the words of one participant: “Sometimes miscommunication between the hospital and shelter is a problem – they send you there, but you can’t get in.” Only 19 % (19/98) of participants reported that once they arrived at the shelter, shelter staff discussed their last hospital care or discharge instructions with them.

Recommendation 3: Discharge Planning Should Include Safe Transportation

Participants were particularly concerned about the safety of public transportation or walking if discharge occurred after dark. One participant explained: “They should make sure people don’t leave late at night and that they have a safe ride to a safe place to stay.” Sixty-seven percent of (66/98) participants stayed at a shelter on the night of their discharge, 17 % (17/98) stayed with friends, family, or had another arrangement, and 11 % (11/98) stayed on streets the first night after discharge (Table 3). While most study participants reported discharge before dark, 27 % (27/98) reported discharge after dark for their most recent acute care episode. Furthermore, 59 % (58/98) reported no safe post-discharge transportation plan. Among those who did have a transportation plan, 13 % (13/98) took public transportation, 10 % (10/98) got a ride from someone they knew, and 14 % (14/98) took a taxi (Table 3).

Community Feedback and Actions in Response to Recommendations

Through feedback during our data dissemination efforts, we gained insights into local systems issues for hospitals and shelters. Senior leaders in both institutions reported that initiatives over the last decade to address related issues had all lapsed, due to limited funding or limitations of individuals working in single institutions without broader support from larger, inter-organizational groups. Therefore, in response to our findings, an ad hoc committee composed of shelter and hospital staff formed to explore ways to ensure timely communication and coordination of discharge care for homeless patients, beginning with their initial presentation and culminating in safe transfer to the shelter at discharge. Initially, two emergency beds at Columbus House were reserved nightly for this purpose, but staff at both hospital and shelter quickly discovered that while these two beds provided the critical piece for appropriate discharge plans, they did not meet the needs of patients who need recuperative care. Furthermore, the logistics of such an informal arrangement were not sustainable without formalized protocols and funding.

These realizations led to the establishment of a formal Respite Task Force, which convenes monthly at Columbus House and is comprised of 17 members representing the hospital, shelter, FQHC, university, community organizations, and state government. Medical respite care is defined by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council as, “acute and post-acute medical care for homeless persons who are too ill or frail to recover from a physical illness or injury on the streets, but who are not ill enough to be in a hospital,”27 and has been shown to improve outcomes for homeless patients,28,29 including permanent supportive housing.30 The overall goal of the Columbus House Respite Task Force is to explore policies and procedures necessary to establish the first respite care center in New Haven.31 Finally, to ensure funding for continued collaboration with healthcare providers, Columbus House successfully applied for external funding that provides for the training and deployment of two shelter-based patient navigators to help homeless patients with post-discharge coordination of care.32 Columbus House and Yale-New Haven Hospital have also partnered as leaders in a statewide application to create systems of care that would improve healthcare for patients who are homeless or are at risk for homelessness. This program enables partnerships between hospitals and community-based organizations to improve care while reducing costs, and is one of several Medicare innovations funded by the Affordable Care Act.33

DISCUSSION

Homeless individuals describe several important barriers to more effective care through integration of hospitals and shelters as overlapping systems of care. First, the majority of participants reported they were not asked about housing while in the hospital; nor were they asked about hospital care while in the shelter. These findings suggest that these issues were not prioritized within each system – hospital providers focused on healthcare, while shelter providers focused on housing, without significant overlap. Our group also recently reported that lack of housing assessment is associated with lower performance of key discharge components by hospital staff (such as discussing costs of medications or diet recommendations), which may result in low-quality discharge instructions for these patients.34 Thus, a first step to better systems integration may be increased awareness among providers at hospitals and shelters, and increased efforts to engage patients who utilize both systems in discussions about relationships between health and housing status.

Second, even once hospital providers identified housing issues among hospitalized patients in our study, deficits in coordination and communication between the two systems may have resulted in patients being discharged to the shelter, only to be turned away because the discharge occurred too late in the day. Such system failures are worrisome because of the high rate of victimization in this population,35,36 especially among women and the elderly,37,38 and they are associated poor health outcomes.39 These failures are also important because they represent missed opportunities to improve outcomes of care. Previous studies have shown that homeless patients with more robust social support networks report less victimization and improved health outcomes.40 Furthermore, discharge from hospital has been described as a “critical time” to address homelessness, and there is evidence to suggest that timely interventions may reduce time to supportive housing.41 Data from our community suggests that hospitalization is a precipitating event for loss of housing for 5 % of individuals experiencing homelessness at a given point in time.21

Our findings have important policy implications at several levels. At the level of individual communities, many have called on healthcare providers to integrate hospital-based and shelter-based care.15 Indeed, the New Haven 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness specifically aims to “Improve discharge planning from local hospitals by making connections to appropriate case management and community services upon admission of a homeless individual to the hospital.”42 At the level of the healthcare system, many studies have shown that a small number of high-utilizers of acute care account for a disproportionate share of overall costs for programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.,43,44 Targeted interventions to improve the coordination of care for these most vulnerable, high-use patients can both improve patient outcomes and reduce overall costs of care.45,46 Our work underscores the need for community engagement in order to successfully implement such interventions across the healthcare system. Finally, these efforts in the healthcare system and individual should be seen in the broader context of a growing movement to eradicate homelessness as an extreme manifestation of disparities in health in developed nations.2,47,48

The CBPR to research has several advantages for acting on these implications. First, by prioritizing community participation and action as important “results,” CBPR enables researchers, healthcare providers, and community members to engage in rapid cycles of learning and application together in real-time. This allowed us to innovate by discussing best practices identified in the literature,14,49 in light of our own results, adapt these practices for our community, and continue to re-assess and adjust. Second, given community feedback about the importance of creating sustainability alongside innovation, we cultivated relationships between organizations and laid the groundwork for lasting collaboration through shared priorities. Thus, the project has continued to grow even as leadership for the project has changed due to career transitions of the initial project leaders (SRG and RA). Finally, beyond the relationships and collaborations built around this specific project, continued development of CBPR as a key community initiative within the Yale School of Medicine has created a broader infrastructure for community-focused collaboration. As these collaborations grow, they contribute to an environment where trust and mutual respect between community leaders and university researchers can facilitate improved health and healthcare for the most vulnerable populations within our community.

These advantages notwithstanding, our study has several limitations. First, data from our semi-structured interviews about experiences during prior hospitalizations may be subject to recall bias. We attempted to limit this bias by focusing on only the most recent acute care visit, and by interviewing only patients with a visit in the past year. Second, we recruited patients from one community; the experiences of homeless individuals in other communities may differ significantly and our results may not be generalizable outside the community we sampled. Third, our sample was predominantly male (80 %) and while this is similar to national (62-67 %)2,9 and state (70 %)15 population estimates for single, homeless adults, the percentage of women and families among the homeless is rising, and deserves specific attention in future research. Fourth, although we sought direct participation by homeless individuals in the framing of our research project, refining survey questions, and giving feedback on results, we recognize that using a more strict application of CBPR methodology, even greater participation is possible. Continuing work from this project can build on this initial experience and increase participation by homeless individuals in ongoing implementation and evaluation of a respite facility in New Haven. Finally, we did not collect outcomes of the transitions in care our participants experienced, so we cannot describe the clinical impact of poorly-coordinated transitions. Nonetheless, we believe that our results identify important areas for future research and key areas for improvement in the transition care provided to these vulnerable patients. Our results can also provide a framework on which to build more collaborative relationships between hospitals and shelters in our community and others.

In conclusion, homeless patients described barriers to high-quality transitions in care from the hospital to the shelter, related to inadequate coordination between providers in both settings. Health care providers should strive to consistently assess housing status and arrange safe transportation, especially after dark, to improve discharge safety of homeless patients and avoid discharge to the streets without shelter. Improved integration of hospitals and shelters as overlapping systems of care within a community may improve the quality of transitions and outcomes of care for homeless patients who rely on these institutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully recognize the contributions of the members of our community who made this project possible. First, we thank the individuals experiencing homelessness who participated in pre-study and post-study focus groups, in addition to those who directly contributed to data collection by enrollment in the study. Similarly, our study would not be possible without the specific contributions of the staff at Columbus House including: Alison Cunningham, Malynda Mallory, Preston Fox, Kevin Guess and Ron Dunhill. We would also like to thank members of the Yale Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Steering Committee on Community Projects, the Yale New Haven Hospital Department of Social Work (Paula Crombie and Kathleen Tynan-McKiernan), the Cornell-Scott Hill Health Center Homeless Healthcare program and the Yale Homelessness and Hunger Action Panel.

We would also like to thank RWJF and the US Department of Veterans Affairs for funding through the Clinical Scholars program. The Yale Clinical Center for Investigation also supported the specific efforts of this program to develop community-based participatory research projects. Additionally, Dr. Wang is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI, K23 HL103720).

Data from this paper were presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine and recognized with the Mack Lipkin Sr. Award for best presentation by an Associate Member.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the RWJF, the VA, or the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt, M. Causes of the Growth of Homelessness During the 1980s. In Understanding Homelessness: New Policy and Research Perspectives, Fannie Mae Foundation, 1997. Available from the Fannie Mae Foundation, 4000 Wisconsin Avenue, NW, North Tower, Suite One, Washington, DC 20016-2804.

- 2.Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. United State Interagency Council on Homelessness. 2010. Available at: http://www.usich.gov/opening_doors/the_plan/. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 3.US Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2009 annual homeless assessment report to Congress 2009. June 18, 2010. http://www.hudhre.info/documents/5thHomelessAssessmentReport.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 4.Kushel MD, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushel MD, Perry S, Bangsberg D, et al. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(5):778–84. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore G, Gerdtz MF, Hepworth G, Manias E. Homelessness: patterns of emergency department use and risk factors for re-presentation. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(5):422–7. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.087239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrow SM, Herman DB, Córdova P, Struening EL. Mortality among homeless shelter residents in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(4):529–34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, Spencer R, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(5):304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Conference of Mayors. 2008 Status Report on Hunger & Homelessness. Available from http://usmayors.org/pressreleases/documents/hungerhomelessnessreport_121208.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 10.Aron LY, Sharkey PT. The 1996 National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients. Prepared by the Urban Institute for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/homelessness/nshapc02/index.htm. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 11.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR 3) Finding Summary. HMIS-Info: http://www.hudhre.info/documents/2010HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012; 2008.

- 12.Han B, Wells BL. Inappropriate emergency department visits and use of the health care for the homeless program services by homeless adults in the northeastern United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9(6):530–7. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ku BS, Scott KC, Kertesz SG, Pitts SR. Factors associated with use of urban emergency departments by the U.S. homeless population. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(3):398–405. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backer TE, Howard EA, Moran GE. The role of effective discharge planning in preventing homelessness. J Primary Prevent. 2007;28:229–43. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Coalition to End Homelessness. A New Vision: What is in Community Plans to End Homelessness? http://www.endhomelessness.org/content/article/detail/1397 Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 16.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, et al., editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Columbus House, Inc. Information available at: www.columbushouse.org. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 19.Immanuel Baptist shelter. Information available at: http://www.esmsshelter.org/index.php. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 20.Martha’s Place shelter. Information available at: http://www.nhhr.org/what-we-do/Services/MarthasPlace/mp.html. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 21.Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness. Connecticut Counts 2009: Point in Time Homelessness Count. Available at: http://www.cceh.org/files/publications/2009_pit_report.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 22.Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119(19):2633–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WK Kellogg Foundation Evaluation Handbook. Battle Creek, Mich: WK Kellogg Foundation; 1998:1–110.

- 24.Yale Hunger and Homelessness Action Project. Information available at: http://www.yale.edu/yhhap/YHHAP.html. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 25.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Medical Respite. Information available at: http://www.nhchc.org/resources/clinical/medical-respite/ Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 28.Buchanan D, Doblin B, Sai T, Garcia P. The effects of respite care for homeless patients: a cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2006Jul;96(7):1278–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kertesz SG, Posner MA, O’Connell JJ, Swain, et al. Post-hospital medical respite care and hospital readmission of homeless persons. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(2):129–42. doi: 10.1080/10852350902735734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Respite Care Providers Network offers implementation “toolkits” to assist communities in creating and sustaining a new respite facility. Information available at: http://www.nhchc.org/resources/clinical/medical-respite/respite-care-providers-network/ Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Recovery Support Services: Behavioral Health Peer Navigator program. Information available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/grants/blockgrant/BH_Peer_Navigator_05-06-11.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 33.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Health Care Innovation Challenge. Information available at: http://innovations.cms.gov/Files/x/Health-Care-Innovation-Challenge-Funding-Opportunity-Announcement.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 34.Greysen SR, Allen R, Rosenthal MS, Lucas GI, Wang EA. Improving the quality of discharge care for the homeless: a patient-centered approach. J Health Care Poor Underserved. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Kushel MB, Evans JL, Perry S, Robertson MJ, Moss AR. No door to lock: victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2492–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR. Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(1):62–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heslin KC, Robinson PL, Baker RS, Gelberg L. Community characteristics and violence against homeless women in Los Angeles County. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(1):203–18. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dietz T, Wright JD. Victimization of the elderly homeless. Care Manag J. 2005;6(1):15–21. doi: 10.1891/cmaj.2005.6.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam JA, Rosenheck R. The effect of victimization on clinical outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(5):678–83. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hwang SW, Kirst MJ, Chiu S, Tolomiczenko G, Kiss A, Cowan L, Levinson W. Multidimensional social support and the health of homeless individuals. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):791–803. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9388-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herman DB, Conover S, Gorroochurn P, Hinterland K, Hoepner L, Susser ES. Randomized trial of critical time intervention to prevent homelessness after hospital discharge. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(7):713–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.7.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.City of New Haven 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness. Available at: http://www.cceh.org/pdf/typ/newhaven_typ.pdf Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 43.Billings J, Mijanovich T. Improving the management of care for high-cost Medicaid patients. Health Aff. 2007;26:1643–54. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raven MC, Doran KM, Kostrowski S, Gillespie CC, Elbel BD. An intervention to improve care and reduce costs for high-risk patients with frequent hospital admissions: a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:270. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shumway M, Boccellari A, O’Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Health Care for the Homeless Council. Information available at www.nhchc.org. Accessed May 11, 2012.

- 48.Geddes JR, Fazel S. Extreme health inequalities: mortality in homeless people. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2156–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60885-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Best JA, Young A. A SAFE DC: a conceptual framework for care of the homeless inpatient. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:375–81. doi: 10.1002/jhm.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]