Abstract

PURPOSE

To erform a process analysis of missed and delayed diagnoses of breast and colorectal cancers to identify: (1) the cognitive and logistical factors that lead to these diagnostic errors, and (2) prevention strategies.

METHODS

Using 56 cases (43 breast, 13 colon) of missed and delayed diagnosis, we performed structured analyses to identify specific points in the diagnostic process in which errors occurred. Each error was classified as either a cognitive error or logistical breakdown. Finally, two physician-investigators identified strategies to prevent the errors in each case.

RESULTS

Virtually all cases involved one or more cognitive errors (53/56, 95 %) and approximately half (31/56, 55 %) involved logistical breakdowns. The clinical activity most prone to cognitive error was the selection of the diagnostic strategy, both during the office visit (25/56, 45 %) and during interpretation of test results (22/50, 44 %). Arrangement of follow-up visits with a primary care physician (8/29, 28 %) or specialist physician (7/29, 26 %) were especially prone to logistical breakdowns. Adherence to current clinical guidelines could have prevented at least one error in 66 % of cases and assistance from a patient advocate could have prevented at least one error in 48 % of cases.

CONCLUSIONS

Cognitive errors and logistical breakdowns are common among missed and delayed diagnoses of breast and colorectal cancers. Prevention strategies should focus on ensuring improving the effectiveness and use of clinical guidelines in the selection of diagnostic strategy, both during office visits and when interpreting test results. Tools to facilitate communication and to ensure that follow-up visits occur should also be considered.

KEY WORDS: diagnosis errors, medical errors, breast cancer, colo-rectal cancer, malpractice

INTRODUCTION

Timely and accurate diagnosis is a critical element of high quality care for patients with breast and colorectal cancers, as early treatment can dramatically improve prognosis. However, errors in diagnosing these cancers occur and are a frequent source of expensive malpractice claims.1–7 Studying them is extremely challenging8 because missed diagnoses generally involve acts of omission, rather than commission,9 which are elusive, and when they are identified, there is rarely enough information in medical records to support thorough causal analyses.

Malpractice claim files provide a rich source of information on breakdowns in the diagnostic process.8,10 Claim files, which are compiled by liability insurance companies during the litigation, typically contain quite detailed documentation on the episode of care in dispute. In addition to the medical record, they include depositions, expert opinions, the plaintiff’s detailed allegation, results of medical examinations of the plaintiff, and sometimes, reports of internal investigations into the alleged event.

In a large review of malpractice claim files conducted as part of a prior study,2 we identified 181 episodes of care in which diagnostic errors had occurred; 56 of these episodes involved breast or colorectal cancer. Missed and delayed diagnosis of these two conditions was the most prevalent type of diagnostic error identified.8 These 56 cases form the focus of this study. They warrant in-depth analysis for three reasons. First, breast and colorectal cancer have a relatively high incidence, both in the population and in malpractice claims. Second, as typically slow-growing tumors, these cancers may present multiple opportunities for interventions to reduce risks of late detection. Third, clinical guidelines for aiding diagnosis of these cancers are available, but it is unclear which points in the care process are most prone to error. This study uses innovative mapping techniques to characterize the diagnostic errors that occurred in these 56 cases and suggests possible prevention strategies.

METHODS

Overview

This study is an in-depth analysis of narrative and quantitative data gathered in a previous multi-regional US study of missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting.2,8 The analysis proceeded in three steps. First, we developed a clinical activity flowchart to describe the standard sequence of activities that typically occurs in the diagnostic process. We then mapped the events in each missed and delayed diagnosis case in our sample onto the clinical activity flowchart, using the abstracted narrative and quantitative data to locate the specific steps in the diagnostic process in which errors occurred. Second, using existing care algorithms, we developed a decision-making model, which describes decisions made at several key points in the process of diagnosing breast and colon cancer. We then overlaid the decision-making model with information from each case to identify the specific decision points at which errors occurred. Finally, we judged the likelihood that each of several prevention strategies might have prevented the cognitive errors or logistical breakdowns in each case.

Claims File Review

The sampling and review methodology for the parent study have been described in detail elsewhere.2,8,10 This study involved claims alleging missed or delayed diagnosis, defined as allegations that an error in diagnosis or testing caused a delay in appropriate treatment, or a failure to act or follow-up on diagnostic test results. Physicians trained in the use of the study instruments reviewed these claims and recorded details of the adverse outcome the patient experienced, the clinical circumstances surrounding it, and the cognitive-, system-, and patient-related factors that may have contributed to the adverse outcome. Next, reviewers judged whether the adverse outcome was due to one or more diagnostic errors. Finally, for claims judged to involve a diagnostic error, reviewers recorded additional clinical information about the error, including who was involved, the setting, where in the diagnostic process breakdowns occurred, and, if evident, why specific breakdowns occurred. On average, reviews took 1.4 h per file.

Study Sample

From a total of 307 claims alleging missed or delayed diagnosis in the physician’s office or other ambulatory settings, 181 (59 %) were judged to involve adverse outcomes due to diagnostic error. In 59 % (107/181) of those claims involving error, the diagnosis at issue was cancer, with breast (n = 44) and colorectal cancer (n = 13) being the most common types. One of the 44 breast cancer claims was excluded from the current analysis because the disputed care involved delays in diagnosing metastasis in a patient with a known history of stage III breast cancer rather than problems in the initial diagnosis of cancer. The course of care in the remaining 56 “cases” of missed breast and colon cancer is the focus of this analysis.

Clinical Activity Flowchart

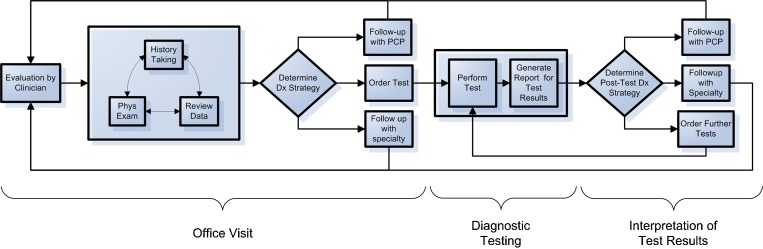

To facilitate the identification of the specific points in care in which breakdowns occurred, we developed a conceptual framework describing the major clinical activities associated with diagnosis of cancer in the ambulatory setting. Drawing on prior work6,7,11–14 and the clinical experience of the investigators, the model divides the diagnostic process into three phases: (1) office visit, (2) diagnostic testing, and (3) interpretation of test results (Fig. 1). Each phase consists of several basic steps on the path towards a final diagnosis, starting from the patient’s initial presentation (e.g., identification of a breast lump in an office consultation) through final diagnosis (e.g., biopsy confirming breast cancer). The model also accounts for the possibility that patients may pass through these phases multiple times.

Figure 1.

Clinical activity flowchart: clinical activities associated with the diagnostic process.

Decision-Making Model

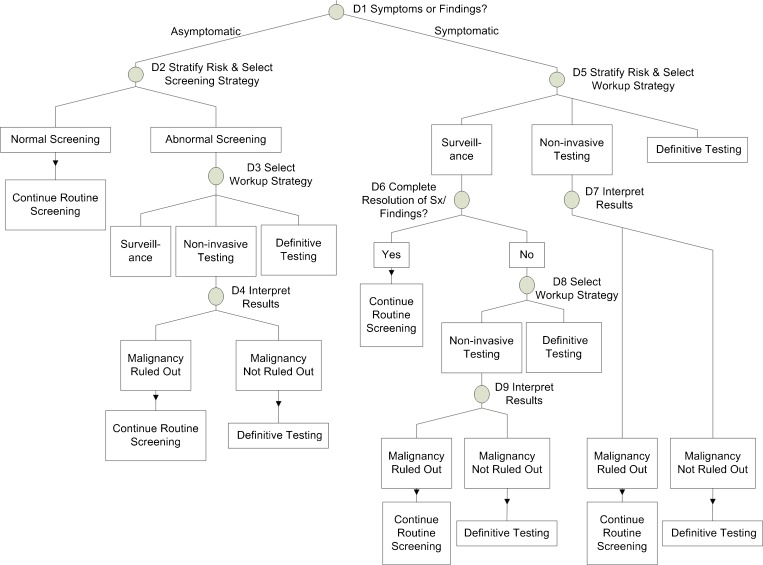

Based on previous research1,8,10,15,16, we anticipated that cognitive errors associated with decision making would figure prominently among the chief causes of missed cancer diagnoses. Using published guidelines for diagnosing breast17 and colorectal18 cancers, we developed a second model that plotted the major decision points in the process of diagnosing cancer (Fig. 2). (This model essentially drills into the two general steps denoted by diamonds in the clinical activity flowchart.)

Figure 2.

Diagnostic decision points for breast and colon cancer.

Mapping Cases to Clinical Activity Flowchart and Decision-Making Model

We reviewed structured and free-text narrative information abstracted from the claim files during the parent study, and then mapped each case in the study sample on to the clinical activity flowchart and decision-making model. With the clinical activity flowchart, the mapping involved two steps. We first determined which activities occurred. When a clinical activity occurred, we then determined whether a cognitive error or logistical breakdown occurred during that particular activity. Cognitive errors were defined as errors due to a lack of clinical knowledge or poor judgment on the part of the involved clinician. Examples include ordering an inappropriate test, misreading a mammography film, or choosing an inappropriate follow-up period. Logistical breakdowns were defined as failures to execute a plan or carry out an activity, despite a clinically appropriate intention to do so. Colloquially, logistical breakdowns are referred to as “fumbles”15 or “dropped balls.” Typical examples are instances of poor communication (clinician-clinician or clinician-patient) or failure to ensure follow through with the clinical plan.

Mapping data from the cases on to the decision-making model involved a similar process. For each case, we determined which of the nine decision points were encountered during the course of care, and for each point that was encountered, whether a cognitive error occurred there.

Identification of Possible Prevention Strategies

For each case, two physician reviewers independently classified on a 5-point Likert scale if any of the following six strategies might have mitigated the error in it (or, in cases with multiple errors, at least one): (1) adherence to currently-available care management guidelines for diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer; (2) assistance from a non-clinical but meticulous patient advocate during the diagnostic process, (3) improved communication, either between providers and the patient, or among providers; (4) improved handoffs between providers as patient sought care from multiple providers; (5) improved transmission of test results; and (6) improved access to medical records (including old films or pathology slides). These prevention strategies were identified based on facilitated discussion groups convened by the parent study. The 5-point Likert scale was dichotomized for further analysis, and differences between the two physicians were resolved by consensus in all discrepant cases. We calculated kappa statistics based on the reviewers’ initial determinations.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We examined the characteristics of the claims, patients, and injuries in the study sample. For the clinical activity flowchart, we calculated the percentage of cases with cognitive errors or logistical breakdowns overall and for each phase in the clinical activity flowchart. For the decision-making model, we calculated the percentage of cases with errors at each point. Confidence intervals were calculated using the binomial method.

RESULTS

Case Characteristics

Patients involved in the cases were an average age of 46.5 years at the time the diagnostic error occurred. Delays averaged 15.2 months for the breast cancer cases and 23.6 months for the colorectal cancer cases. Overall, 53 % of the patients involved suffered major physical injury (typically, through a substantial worsening of their prognosis) and 25 % died as a result of the missed or delayed diagnosis. Other characteristics of the 56 cases are shown in Table 1. Table 2 provides examples of five illustrative cases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Cases

| Breast cancer | Colon cancer | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 43 | 13 | 56 |

| Gender (% female) | 100 % | 54 % | 89 % |

| Average age (± SD)* | 43.6 (±12.7) | 56.1 (±11.7) | 46.5 (±13.4) |

| Medical insurance | |||

| Private insurance | 66 % | 61 % | 65 % |

| Public insurance | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % |

| Uninsured | 7 % | 0 % | 5 % |

| Unknown | 27 % | 38 % | 30 % |

| Average year of eventual diagnosis | 1997 | 1997 | 1997 |

| Average delay in diagnosis† (months) (median, IQR) | 15.2 (9.1, 24.4) | 23.6 (20.7, 27.6) | 18.1 (10.5, 25.8) |

| Degree of injury | |||

| No injury | 2 % | 0 % | 2 % |

| Emotional disability only | 2 % | 8 % | 4 % |

| Minor physical | 2 % | 8 % | 4 % |

| Significant physical | 16 % | 0 % | 12 % |

| Major physical | 59 % | 31 % | 53 % |

| Death | 16 % | 54 % | 25 % |

| Not characterized | 2 % | 0 % | 2 % |

IQR = Interquartile range

*Patient’s age at the time the diagnostic error occurred

†Defined as the interval between the date on which the diagnosis should reasonably have been made and the date it was made

Table 2.

Example of Cases and Errors Identified (may be published on-line)

| Cancer type | Description of clinical events | Errors identified |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | 35-year-old female with family history of breast cancer presents with breast lump. Initial workup with a mammogram was negative and further workup was not pursued | (1) Failure of PCP to work up breast lump completely; (2) reliance by PCP on negative mammogram result as evidence that no further workup required; (3) failure of PCP to recognize the incomplete resolution of breast lump requires further workup |

| 41-year-old female presents for routine screening mammogram. Mammogram read as normal, but in retrospect had a suspicious-looking lesion. Patient presents 6 months later with breast lump and ultimately diagnosed with locally invasive breast cancer | (1) Failure of radiologist to correctly interpret mammogram films | |

| 60-year-old female presents with a breast mass, and no biopsy was recommended because recent mammograms were read as a fibroadenoma. Patient later presented to another physician who arranged for a breast biospy that revealed cancer | (1) Failure of PCP to completely work up breast lump; (2) reliance by PCP on negative mammogram as evidence that no further workup is necessary; (3) failure of radiology to mention cancer on the differential diagnosis on the mammogram report | |

| Colorectal cancer | 52-year-old male who presented with new-onset lower abdominal pain associated with constipation. Patient diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia and barium enema ordered but did not occur. Patient subsequently diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer during an abdominal ultrasound | (1) Failure by PCP to completely work up iron deficiency anemia; (2) failure to track barium enema order to completion; (3) inadequate follow-up |

| 64-year-old female presented with anemia. Workup revealed vitamin B12 deficiency and borderline iron deficiency. Anemia transiently improved with vitamin B12 supplement, but patient subsequently found to have recurrence of anemia during an unrelated urgent care visit. Patient presented 1 year later with change in stool color and diagnosed with cancer | (1) Failure to completely work up anemia; (2) failure by second physician to correctly interpret low hematocrit value as needing workup |

Cognitive and Logistical Breakdowns by Clinical Activity

Ninety-five percent of cases (53/56) involved a cognitive error in at least one of the three phases of care, and 55 % (31/56) involved a logistical breakdown in at least one phase (Table 3). Cognitive errors occurred during the office visit in 61 % of cases, during diagnostic testing phase in 39 %, and during interpretation of test results in 48 %. Logistical breakdowns occurred during the office visit in 43 % of cases, during diagnostic testing in 20 %, and during the interpretation of tests in 16 %.

Table 3.

Cognitive and Logistical Breakdowns in Diagnosis of Breast and Colon Cancer by Clinical Activity

| Care phase | Clinical activity | Cases in which activity took place | Cases with cognitive error identified during activity | Cases with logistical breakdown identified during activity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | n | % | ||

| Office visit | Overall | 56 | 34 | 61 | 24 | 43 |

| History taking | 56 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 | |

| Physical exam | 55 | 14 | 25 | 1 | 2 | |

| Data review | 51 | 8 | 16 | 13 | 25 | |

| Determine diagnostic strategy | 56 | 25 | 45 | n/a | n/a | |

| Arrange for follow-up with pcp | 29 | 9 | 31 | 8 | 28 | |

| Arrange for follow-up with specialist | 27 | 3 | 11 | 7 | 26 | |

| Order diagnostic test | 56 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 18 | |

| Diagnostic testing | Overall | 56 | 22 | 39 | 11 | 20 |

| Performance of test | 56 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 | |

| Generation of test result report | 56 | 20 | 36 | 8 | 14 | |

| Interpretation of test results | Overall | 56 | 27 | 48 | 9 | 16 |

| Determine post-test diagnostic strategy | 50 | 22 | 44 | n/a | n/a | |

| Arrange for follow-up with pcp | 27 | 6 | 22 | 2 | 7 | |

| Arrange for follow-up with specialist | 39 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 | |

| Order further diagnostic test | 11 | 2 | 18 | 5 | 45 | |

| Any care phases | 56 | 53 | 95 | 31 | 55 | |

The clinical activity most prone to cognitive error was determination of the diagnostic strategy, either in the office visit (25/56, 45 %) or during interpretation of test results (22/50, 44 %). One common example of this type of breakdown among the breast cancer cases was reliance on a negative mammogram result in a relatively young patient who presented with a breast lump as evidence that no further workup was needed. Other activities associated with relatively high probabilities of cognitive errors were the generation of test result reports and arranging for follow-up with the patient’s primary care physician, with the choice of an inappropriately long follow-up period being a common example of the latter error.

Logistical breakdowns occurred in 25 % (13/51) of cases in which clinicians reviewed clinical data on the patient, typically when the clinician did not have ready access to clinical information collected by another clinician or facility. Arrangement of follow-up visits, either with a primary care physician (8/29, 28 %) or a specialist physician (7/29, 26 %), were other activities prone to logistical breakdowns, with the failure of a follow-up visit or referral to occur as intended being a common example.

Decision Points and Cognitive Errors

Errors rarely occurred in determining whether the patient was symptomatic or asymptomatic (3/50, 6 %) (Table 4). However, cognitive errors occurred in 46 % (19/41) of cases in which clinicians were called upon to select the workup strategy for a symptomatic patient (e.g., ordering a mammogram alone when a breast ultrasound should also have been ordered). Cognitive errors occurred in 52 % (15/29) of cases in which the clinician had to interpret the results of non-invasive testing (e.g., decision that a negative mammogram was sufficient to rule out the presence of cancer). In addition, although it only occurred in a minority of cases in which clinicians were called upon to determine whether the patient’s presenting symptoms had resolved after a period of surveillance, cognitive errors occurred in half of them (8/16), where the clinician failed to pursue further workup despite incomplete resolution of symptoms.

Table 4.

Cognitive Errors During Selection of Diagnostic Strategy by Decision Point

| Decision point | Label on figure 2 | No. of cases in which decision point reached | No. of cases with cognitive error at decision point | Proportions of decisions made with cognitive error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determine whether patient is symptomatic or asymptomatic | D1 | 50 | 3 | 6 % |

| Stratify risk and select screening strategy, given provider determined patient to be asymptomatic | D2 | 17 | 4 | 24 % |

| Select further diagnostic workup strategy, given screening test was abnormal | D3 | 9 | 4 | 44 % |

| Interpret results of non-invasive testing in the setting of abnormal screening test | D4 | 8 | 2 | 25 % |

| Stratify risk and select workup strategy, given provider determined patient to be symptomatic | D5 | 41 | 19 | 46 % |

| Interpret results of non-invasive testing for symptomatic patient | D7 | 29 | 15 | 52 % |

| Determine whether symptoms have completely resolved, given provider decided to pursue surveillance as the workup strategy for symptomatic patient | D6 | 16 | 8 | 50 % |

| Select workup strategy, given symptoms have not completely resolved after surveillance | D8 | 9 | 2 | 22 % |

| Interpret results of non-invasive test in the setting of symptoms that do not resolve after period of surveillance | D9 | 8 | 4 | 50 % |

Prevention Strategies

In 66 % (36/55) of the cases, reviewers judged it more likely than not that the full application of the care management guidelines on breast or colorectal cancer, as appropriate, would have mitigated at least one error in the case (Table 5). Assistance from a patient advocate throughout the diagnostic process could have prevented at least one logistical breakdown in 48 % (27/56) of the cases. Improved communication, either among providers or between providers and patients, was judged likely to prevent error in 35 % of the cases. Improved handoffs might have prevented an error in 32 % of cases. Across the six prevention strategies, the agreement between the two physician reviewers was fair, with an average kappa score of 0.39.

Table 5.

Anticipated Effect of Prevention Strategies

| Prevention strategy | Proportion of cases with error prevented | N |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption of diagnostic guidelines on breast and colorectal cancers | 66 % | 55* |

| Assistance from a non-clinical but meticulous patient advocate throughout the diagnostic process | 48 % | 56 |

| Improved communication (either among providers or between provider and patient) | 35 % | 55* |

| Improved provider to patient communication | 30 % | 56 |

| Improved provider to provider communication | 21 % | 55* |

| Improved handoff as patients shuttled among providers | 32 % | 56 |

| Improved communication of test results (either among providers or between provider and patients) | 12 % | 56 |

| Improved access to medical records (including old films) | 14 % | 56 |

*One case was omitted from these analyses because insufficient information in the malpractice chart did not allow reviewers to come to consensus

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed 56 episodes of care in which diagnoses of beast or colon cancer were missed or delayed. Virtually all of these cases involved cognitive errors and approximately half involved logistical breakdowns. Determination of the diagnostic strategy, both during the office visit and during review and interpretation of test results, were “hot spots” for cognitive error, suggesting that both of these two care phases with their distinct clinical workflows deserve attention in the prevention of cognitive errors. Cognitive errors were often due to clinicians selecting the wrong workup strategy or misinterpreting the results of non-invasive testing. Additionally, the arrangement of follow-up care with primary care physicians and specialists was shown to be particularly prone to logistical breakdowns. Our study also highlights the co-existence of cognitive and logistical factors in the diagnosis of cancer.

Previous studies have highlighted the need to reduce diagnostic errors using strategies such as educational interventions to improve the recognition of symptoms or interpretation of reports by physicians7, improving communication within the ‘triangle’ of primary care providers, cancer specialists, and patients7, and focusing on follow-up and feedback.19 Our study points to several practical strategies for preventing diagnostic errors. The high proportion of cases involving cognitive errors during the selection of a diagnostic strategy underlines the value of effective decision aids during this clinical step. Care guidelines and diagnostic algorithms integrate the best available evidence with the experience of clinical experts to guide busy clinicians toward selecting the appropriate strategy. Many such tools have been constructed and disseminated by professional organizations and risk management organizations, and for a variety of symptoms and disease conditions, including breast and colorectal cancer. However, adoption of these guidelines faces several obstacles.20 For example, physicians often lack the time to look up these algorithms.21 Furthermore, as this study clarifies, clinicians confront decisions about diagnostic strategies at two distinct phases of ambulatory care: during the office visit and during interpretation of test results. Each phase presents different workflow and cognitive challenges. During an office visit, clinicians, especially primary care clinicians, must address a multiplicity of issues and capture clinical decision-making processes efficiently in the visit note. During interpretation of test results, the clinician must review the results of the tests in the context of the patient’s medical history, which may have been obtained weeks or months earlier. Another promising approach may be to design and implement documentation tools that comprehensively support the different activities in the diagnostic process.

Communication problems frequently contributed to errors in the cases we investigated. This suggests a set of complementary strategies to improve communication among providers and between providers and patients. First, patient advocacy groups should continue to press patients to take an active role in their care, and empower patients to ask the appropriate questions during and after the clinical encounter. Second, our study suggests a role for a clinical advocate to help patients navigate the complex medical system, especially for patients with limited health literacy. Third, communication tools should be developed and used consistently during and between clinical encounters. For example, written care plans that are reviewed and an agreed-upon plan at the end of the visit may allow the provider and patient to verify mutual understanding and rectify miscommunications. The written plan may also serve as a memory aid to which patients can refer between clinical encounters. In addition, these care plans could be used as a backup method of communication among providers. Fourth, tracking tools to help clinicians ensure that all follow-up appointments, referrals to other clinicians, and tests have been completed will likely be important.

Many of these prevention strategies will require substantial investment. For example, the widespread use of care management and tracking tools to address patients with multiple ongoing symptoms will likely require the adoption of advanced and interoperable electronic medical records that support problem-oriented documentation, electronic order entry, and tracking of orders. We recognize that many health care organizations may not have the financial or human capital to embrace these strategies currently.22 However, these expenditures must be considered alongside the costs of diagnostic errors, which are high. For example, payouts for the missed and delayed breast cancer diagnoses in our sample averaged $250,000, while payouts for the colon cancer cases averaged $225,000. Payers and malpractice insurance companies, particularly captive insurers, thus have strong financial incentives to facilitate adoption of these important patient safety tools. In addition, federal and payor-driven incentives to spur the adoption of electronic health records,23 patient-centered medical homes,24 and Accountable Care Organizations25 may provide new opportunities to implement these strategies.

Our study has several limitations. First, unlike prospective observational studies or root cause analyses based on discussions with relevant staff immediately after an event has occurred, retrospective review of records, even of the detailed records found in malpractice claim files, may miss certain information, unless they emerged as issues in the litigation. This measurement problem means that prevalence findings for such estimates will be lower bounds, and our results likely understate the true complexity of diagnostic errors. Second, our malpractice claims data may have several other biases. Severe injuries and younger patients are overrepresented in the subset of medical injuries that trigger litigation.26,27 It is possible that the factors that led to error in litigated cases may differ systematically from the factors that led to error in non-litigated cases. Finally, it is possible that the cognitive and logistical issues identified in this study may not entirely reflect those encountered in ambulatory practice, although previous studies on diagnostic errors have identified similar issues.16,28

In summary, we found that both cognitive errors and logistical breakdowns are frequent contributors to missed and delayed diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer. Many of these cognitive errors and logistical breakdowns appear amenable to prevention, chiefly through the widespread adoption of decision aids and communication tools. Findings from this study add weight to calls for investment in the development, implementation, and evaluation of such tools.6,7,9,28

Acknowledgements

Contributors

No relevant contributors beyond the list of study co-authors.

Funders

This study was supported by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HS011886-03) and the Harvard Risk Management Foundation.

Prior Presentations

Material presented in this manuscript constitutes an original secondary analysis of a case series previously published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.4 An early version of the abstract was presented orally at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Conference.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Risk Management Foundation. Reducing Office Practice Risks. Forum 2000;20(2).

- 2.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Yoon C, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. NEJM. 2006;354(19):2024–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Nundy S, Seabury SA. The growth of physician medical malpractice payments: Evidence from the national practitioner data bank. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;W5240–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Phillips RLJ, Bartholomew LA, Dovey SM, Fryer GE. J, Miyoshi TJ, Green LA. Learning from malpractice claims about negligent, adverse events in primary care in the United States. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:121–126. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh H, Sethi S, Ruber M, Petersen LA. Errors in cancer diagnosis: current understanding and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(31):5009–5018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taplin SH, Rodgers AB. Toward Toward improving the quality of cancer care: addressing the interfaces of primary and oncology-related subspecialty care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;40:3–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nekhlyudov L, Latosinsky S. The interface of primary and oncology specialty care: from symptoms to diangosis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;40:11–17. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gandhi TK, Kachalia A, Thomas EJ, Puopolo AL, Yoon C, Brennan TA, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims. Ann Int Med. 2006;145:488–496. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wachter RM. Why diagnostic errors don't get any respect—and what can be done about them. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1605–1610. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kachalia A, Gandhi TK, Puopolo AL, Yoon C, Thomas EJ, Griffrey R, et al. Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(2):196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osherorff JA, Pifer EA, Sittig DF, Jenders RA, Teich JM. Clinical Decision Support Implementers' Workbook. Chicago: HIMSS, 2004.

- 12.Weingart SN, Saadeh MG, Simchowitz B, Gandhi TK, Nekhlyudov L, Studdert DM, et al. Process of care failures in breast cancer diagnosis. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24(6):702–709. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0982-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh H, Weingart SN. Diagnostic errors in ambulatory care: dimensions and preventive strategies. Adv Health Sci Edu. 2009;14(Supp 1):57–61. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9177-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poon EG, Wald J, Bates DW, Middleton B, Kuperman GJ, Gandhi TK. Supporting patient care beyond the clinical encounter: three informatics innovations from partners health care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:1072. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gandhi TK. Fumbled hand-off: One dropped ball after another. Ann Int Med. 2005;142:352–358. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breast Care Management Algorithm. Cambridge: Risk Management Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colorectal Cancer Screening Algorithm. Cambridge: Risk Management Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff GD. Minimizing diagnostic error: the importance of follow-up and feedback. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 suppl):S38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PC, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murff HJ, Gandhi TK, Karson AS, Mort EA, Poon EG, Wang SJ, et al. Primary care physician attitudes concerning follow-up of abnormal test results and decision support systems. Int J Med Inform. 2003;71(2–3):137–149. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller RH, Sim I. Physicians' use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(2):116–126. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meaningful Use. healthit hhs gov [serial online] 2009.

- 24.Singh H, Graber ML. Reducing diagnostic error through medical home-based primary care reform. JAMA. 2010;304(4):463–464. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Inspector General, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Accountable Care Organizations. http://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/accountable-care-organizations/index.asp. 10-21-2011.

- 26.Burstin HR, Johnson WG, Lipsitz SR, Brennan TA. Do the poor sue more? A case–control study of malpractice claims and socioeconomic status. JAMA. 1993;270(14):1697–1701. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510140057029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, Zbar BI, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado [see comments] Med Care. 2000;38:250–260. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh H, Naik AD, Rao R, Petersen LA. Reducing diagnostic errors through effective communication: Harnessing the power of information technology. J Gen Int Med. 2008;23(4):489–494. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0393-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]