Abstract

Background

Duty hour restrictions limit shift length to 16 hours during the 1st post-graduate year. Although many programs utilize a 16-hour “long call” admitting shift on inpatient services, compliance with the 16-hour shift length and factors responsible for extended shifts have not been well examined.

Objective

To identify the incidence of and operational factors associated with extended long call shifts and residents’ perceptions of the safety and educational value of the 16-hour long call shift in a large internal medicine residency program.

Design, Participants, and Main Measures

Between August and December of 2010, residents were sent an electronic survey immediately following 16-hour long call shifts, assessing departure time and shift characteristics. We used logistic regression to identify independent predictors of extended shifts. In mid-December, all residents received a second survey to assess perceptions of the long call admitting model.

Key Results

Two-hundred and thirty surveys were completed (95 %). Overall, 92 of 230 (40 %) shifts included ≥1 team member exceeding the 16-hour limit. Factors independently associated with extended shifts per 3-member team were 3–4 patients (adjusted OR 5.2, 95 % CI 1.9–14.3) and > 4 patients (OR 10.6, 95 % CI 3.3–34.6) admitted within 6 hours of scheduled departure and > 6 total admissions (adjusted OR 2.9, 95 % CI 1.05–8.3). Seventy-nine of 96 (82 %) residents completed the perceptions survey. Residents believed, on average, teams could admit 4.5 patients after 5 pm and 7 patients during long call shifts to ensure compliance. Regarding the long call shift, 73 % agreed it allows for safe patient care, 60 % disagreed/were neutral about working too many hours, and 53 % rated the educational value in the top 33 % of a 9-point scale.

Conclusions

Compliance with the 16-hour long call shift is sensitive to total workload and workload timing factors. Knowledge of such factors should guide systems redesign aimed at achieving compliance while ensuring patient care and educational opportunities.

KEY WORDS: medical education-graduate, medical education, systems-based practice, duty hours

INTRODUCTION

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced duty hour restrictions for post-graduate clinical training programs with the intention of improving patient safety and resident education.1,2 To comply with these restrictions, numerous training programs have implemented non-teaching hospitalist services and physician extenders, resident shift-based staffing, night float admitting schemes, and extended cross coverage periods.3–8 Despite such changes, programs continue to have difficulty achieving compliance with ACGME requirements.9–11

In 2011, the ACGME instituted new mandates, including a mandatory 16-hour shift length limit for residents in their 1st post-graduate year (PGY-1), unless allowed a 5-hour sleep period.12,13 Many programs currently utilize a “long call” admitting model that includes an admitting shift lasting 16 hours on a cycle of one in every three to four days, where house staff perform the majority of their new patient work-ups.14 However, program directors believe it will be difficult to achieve compliance with 16-hour shifts and have raised concern about implementing and financing changes to clinical services to achieve compliance.15,16 Large-scale changes may be untenable for many programs and may include unintended consequences for patient care, provider satisfaction, and education.17–24 Therefore, solutions specifically targeted toward the operational factors most responsible for extended 16-hour shifts may allow for more focused changes to improve compliance while potentially avoiding major system overhauls.

Since the introduction of the 16-hour shift length limit, one study has reported significant non-compliance with this mandate, while no studies have assessed the key operational factors associated with extended shifts in this model.25 To investigate whether the traditional long call admitting model is feasible under these new restrictions, we sought to identify house staff compliance with the 16-hour shift length in a long call admitting model and the factors associated with extended shifts in a large academic residency program. Second, we assessed residents’ perceptions of workload, patient safety, and the educational experience in the long call admitting model.

METHODS

Study Design

We created and administered 2 online surveys to junior and senior residents at a large academic internal medicine program that utilizes a 16-hour long call admitting shift with subsequent night float coverage. Between August of 2010 and January of 2011, the program sent the first survey link via email to each on-call, inpatient medicine ward resident immediately after the call night during 5 inpatient blocks. Following the initial email invitation, one study investigator (JG) sent a reminder email or paging system notification to non-responders within 24-hours. All holidays were excluded from data collection. In mid-December, the program sent the second online survey link via email to all junior and senior residents in the program to globally assess their perceptions of the long call admitting model while on inpatient wards. One week after the initial email invitation, a study investigator (JG) sent a reminder email requesting survey completion. Both surveys were pilot tested by the chief medicine residents and managed through www.surveymonkey.com. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as a quality improvement project.

Characteristics of the Inpatient Ward Service

This large academic residency program consists of 158 total residents. Medicine ward teams consist of 1 junior or senior resident and 2 interns, plus 0 to 2 medical students. Teams take long call admitting shifts of 16 hours every 4th day, admitting patients from 7:00 am to 8:30 pm; team members work until 11:00 pm to complete call-related duties. Night float residents admit patients overnight beginning at 8:30 pm until 7:00 am, evenly distributing overnight admissions among 8 inpatient ward teams. Post-call shifts start at 7:00 am, requiring an 11:00 pm departure time the night prior to ensure 8 hours off.

Call-Shift Survey Instrument

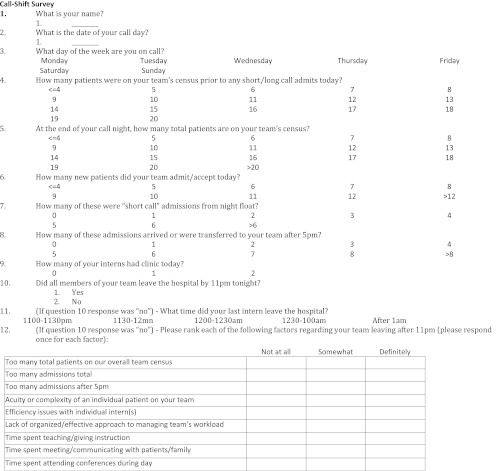

The first survey was developed for the purpose of this study through consensus of the medicine residency program directors, chief medicine residents, and co-investigators to collect data on the occurrence of and factors contributing to extended shifts. Survey items (see Appendix 1) included number of admissions accepted from night float, total admissions accepted during the call shift, total admissions accepted after 5:00 pm, number of interns in clinic on the call day, and whether all members of the team departed the hospital before 11:00 pm. If all team members did not leave before 11:00 pm (thereby exceeding 16-hour shift length), respondents were asked to report the departure time of the last team member and the degree to which certain factors contributed to the extended shift.

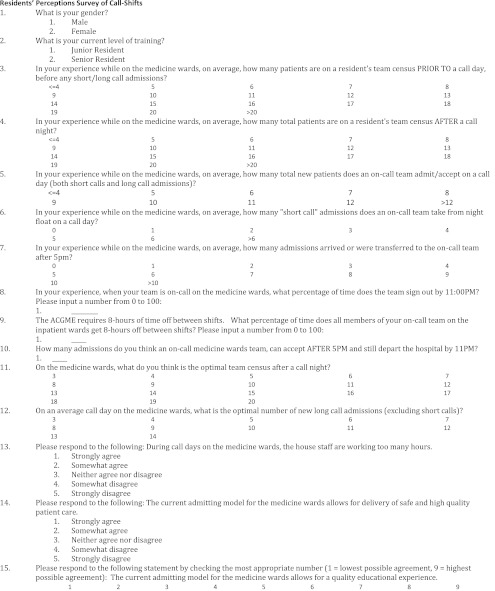

Resident Perceptions of Inpatient Ward Call Shifts Survey Instrument

This second survey (see Appendix 2) was developed for the purpose of assessing residents’ perceptions of optimal number of admissions on call days, overall number of hours worked, the quality of care delivered, and educational value of the 16-hour long call admitting model.

Data Analysis

We defined our outcome variable—an extended shift lasting longer than the scheduled 16 hours—as failure of all team members to depart the hospital by 11:00 pm. We treated call-shift variables as categorical variables, dividing each into tertiles in order to assure adequate sample size for each comparison. The only exception was our variable representing the number of short-call admissions, which we dichotomized at 2 due to a large leftward skew. Bivariable and multivariable associations between our predictors of interest and outcome of having a shift longer than 16 hours were analyzed using logistic regression. Model discrimination was assessed using the c-statistic (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve). Results from the resident perceptions survey (survey 2) are reported descriptively. The data were analyzed using SAS and Stata/IC-8, College Park, Texas.

RESULTS

Call-Shift Data

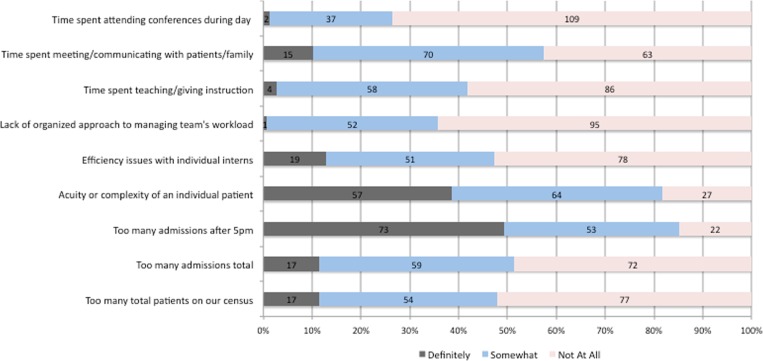

Two-hundred and forty-two on-call surveys were sent electronically, of which 230 were completed (95 % response rate). An estimated 95 % of surveys were completed within 36 hours of shift completion. See Table 1 for participant and overall long call shift characteristics. Overall, 92 of 230 on-call shifts (40 %) included at least 1 team member having an extended shift beyond 11:00 pm, while 30 of the 230 shifts (13 %) included at least one team member having an extended shift beyond 12:00 am. The factors associated with an extended shift are shown in Table 2. The c-statistic of our final multivariable model was 0.83. After adjusting for gender, residency year, day of the week, and the long call shift variables of interest, the factors independently associated with extended shifts were morning census, number of long call admissions, and number of admissions after 5 pm. For each of these variables, greater numbers were associated with increased odds of an extended shift. The strongest predictor of an extended shift was the number of admissions per team after 5 pm, with an odds ratio of 5.2 (1.9–14.3) for 3–4 patients and an odds ratio of 10.6 (3.3–34.6) for > 4 patients. This variable alone accurately predicted 74 % of extended shifts in our cohort (c-statistic = 0.74). Number of short-call admissions and having an intern in clinic on the call day were not significantly associated with extended shifts. For teams with at least 1 team member departing after 11:00 pm, the most commonly reported reasons “definitely” leading to a late departure were “too many admissions after 5 pm” and “acuity of patient on service” (49 % and 39 %, respectively—see Figure 1). Time spent “teaching” and “attending conference” were the least frequently reported reasons for a late departure.

Table 1.

Medicine Resident and 16-Hour Long Call Shift Characteristics (n = 230)*

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 113 (49) |

| Female | 117 (51) |

| Residency year—n (%) | |

| Junior resident | 121 (53) |

| Senior resident | 109 (47) |

| Day of the week—n (%) | |

| Weekday call | 164 (71) |

| Weekend call | 66 (29) |

| Average morning census—median (range) | 5 (0-19) |

| Number of short calls—median (range) | 2 (0-7) |

| Number of long call admits—median (range) | 6 (0-12) |

| Number of admits after 5p—median (range) | 4 (0-9) |

| Any intern in clinic—n (%) | |

| Yes | 28 (12) |

| No | 202 (88) |

| Extended shift | |

| Yes | 92 (40) |

| No | 138 (60) |

* >95 % of surveys submitted within 36 hours of shift completion

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations Between 16-Hour Long Call Shift Variables and Extended Shifts

| Variable—n (%) | Compliant shift n = 138 | Extended shift n = 92 | Unadjusted OR (95 % CI) | Adjusted OR (95 % CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morning census | ||||

| < 5 | 55 (63) | 33 (38) | 1 | 1 |

| 5-6 | 50 (75) | 17 (25) | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) |

| > 6 | 33 (44) | 42 (56) | 2.1 (1.1-4.0) | 2.2 (1.01-4.8) |

| Number of short calls | ||||

| < 2 | 58 (54) | 49 (46) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 2 | 80 (65) | 43 (35) | 0.6 (0.4-1.1) | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) |

| Number of long call admits | ||||

| < 5 | 55 (85) | 10 (15) | 1 | 1 |

| 5-6 | 49 (64) | 27 (36) | 3.0 (1.3-6.9) | 1.0 (0.4-2.8) |

| > 6 | 34 (38) | 55 (62) | 8.9 (4.0-19.8) | 2.9 (1.05-8.3) |

| Number of admits after 5p | ||||

| < 3 | 60 (90) | 7 (10) | 1 | 1 |

| 3-4 | 57 (56) | 44 (44) | 6.6 (2.8-15.9) | 5.2 (1.9-14.3) |

| > 4 | 21 (34) | 41 (66) | 16.7 (6.5-43.0) | 10.6 (3.3-34.6) |

| Any intern in clinic | ||||

| No | 127 (63) | 75 (37) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 11 (39) | 17 (61) | 2.6 (1.2-5.9) | 2.4 (0.9-6.7) |

*Adjusted for all on-call shift variables listed in the table, plus gender, year of residency, and day of the week

Figure 1.

On-Call Residents’ Reported Reasons for Late Hospital Departure (n = 148).

Residents’ Perceptions of Inpatient Ward Call Shifts

Seventy-nine of 96 junior and senior residents completed the online perceptions survey (82 % response rate). When asked how many patients long call admitting teams could accept after 5 pm and still avoid an extended shift, house staff answered 4.5, on average. When asked about the "optimal" number of new admissions on a call day, house staff answered 7, on average. When asked whether house staff worked too many hours in the admitting model,” the majority of respondents were neutral or disagreed with the statement (60 %). When asked whether the current admitting model allowed for “the delivery of safe and high quality patient care,”73 % agreed or strongly agreed. On a scale from 1 to 9 in regards to the admitting model allowing for a “quality educational experience,” 53 % of residents reported a score of 7, 8, or 9.

DISCUSSION

In this medicine residency program with a well-established 16-hour long call shift admitting model, which includes at least 2.5 hours of wrap-up work after the last admission, the long call shift length frequently exceeded the planned 16-hours during the study period. Our findings that greater overall number of admissions and number of late shift admissions were the strongest predictors of extended shifts highlight the sensitivity of duty hour compliance to both total workload and workload timing factors related to newly admitted patients. On-call house staff whose shift length exceeded 16 hours corroborated these findings, identifying multiple late admissions and high patient acuity as the predominant barriers to timely departure. Regarding the long call admitting model, most residents believed the model allowed for the delivery of safe patient care but fewer felt this model allowed for a quality educational experience. These findings raise concern about compliance and education in the 16 hour long call shift model and highlight and anticipate the areas of vulnerability to which creative solutions should be targeted.

Despite increased awareness and education about the 16-hour shift length maximum, a significant proportion of our shifts exceeded 16 hours and, therefore, also did not include sufficient time off prior to subsequent shifts. Following the 2003 ACGME mandates, programs have struggled to achieve compliance with regulations. Landrigan et al. reported nearly two-thirds of inpatient intern months and greater than 85 % of programs and hospitals were in violation.9 Holt et al. reported that nearly 9 % of residents identified “10 hours of rest” between shifts as an area of noncompliance.10 Modifying the admitting model from overnight, 24-hour call to a 16-hour shift, McCoy et al. showed “10-hour violations” increased to approximately 25 %, similar to our results.10,25 These data suggest it may be difficult for programs to achieve full compliance with 16-hour shift lengths and the required time off between shifts.

Given the 16-hour mandate is recent, predictors of extended shifts have not been well described. In a 30-hour admitting model, Arora et al. also identified total admissions on an admitting shift as a predictor for extended shifts.11 In the 16-hour model studied by McCoy et al., residents reported 4 pm to 9 pm as the busiest time of the admitting day, resulting in later departure times.25 Our finding that relatively few admissions (greater than 6 total per 2 intern team) can lead to shift length non-compliance draws attention to the tension between assuring duty hour compliance while preserving primary patient work-ups for interns. The long call admitting day is the only day when ward interns perform primary admission work-ups, and given the relatively low number of admissions predicting extended shifts in the 16-hour long call model, further distributing primary patient work-ups to alternative caregivers not only introduces hand-offs in care but also runs the risk of compromising house staff education derived from primary clinical exposure. Finding the right balance may require moving away from the traditional long call model to models in which teams admit patients daily.

Our results also suggest that finding the right balance between assuring duty hour compliance and adequate numbers of admissions may require changing shift times to better align staffing with flow of newly admitted patients. It is not surprising that the greater the number of admissions arriving within 6 hours of end-of-shift, the more likely the team was to have an extended shift. House staff also perceive this factor as the primary reason for their late departure, corroborating the significance of this timing component as a contributor to extended shifts. As in many hospitals, this flux of late-day admissions is largely dictated by the timing of medical admissions from the Emergency Department, discharge times, and bed availability on the wards. However, changing house staff work shifts to better align staffing with flow of newly admitted patients, while potentially improving compliance with duty hours, might also introduce a multitude of unforeseeable social, educational, and patient care consequences.26–28 For example, house staff coming in at later points in the day may not be able to attend educational conferences, which are traditionally held early in the morning or may not be available to round routinely on previously admitted inpatients and thus miss participating in ongoing medical decision-making throughout the hospital course.

Despite a significant number of non-compliant shifts, our residents believed the 16-hour admitting structure still allows for safe and high quality patient care. The intention of the ACGME duty hour mandates was to improve patient safety and quality, which has been suggested in some studies and remains an active area of research.14,29–31 However, our residents were less confident in the 16-hour long call admitting model allowing for an optimal quality educational experience. Studies have suggested duty hour mandates have had a neutral or negative impact on education, particularly in programs with violations.10 Concern has been raised by residents and faculty following the mandates, with report of less time spent in educational conferences, at the bedside, and in resident autonomy, accountability, and professionalism.22,26,32,33 Therefore, duty hour reform and increased reliance on the 16-hour long call shift may achieve more optimal patient outcomes, but it may come at the expense of residents’ educational experience. The optimal shift duration and timing that balances these 2 ends does not seem clear.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the data are from 1 institution and may not be generalizable. Second, there exists the possibility of social desirability bias since individual names were included in each survey. The house staff were reassured this assessment was to span multiple rotations and was for “systems improvement,” which should have decreased inaccurate reporting. Third, the time of year from late summer to mid-winter did not capture data from later in the academic year when house staff might be more efficient. Additionally, it is possible that many late-in-shift admissions early in the year are more problematic for on-time departure than at later points in the year. Studies should investigate whether time-of-the-year specific shift schedules could be developed that capitalize on the strengths and weaknesses of house staff at various points of the year.

In this study, we found that in a program with a well-established 16-hour long call admitting model, the long call shift length frequently exceeded 16 hours and a greater number of admissions, particularly late in the shift, were strongly associated with extended shifts. Our findings raise questions regarding the feasibility of the traditional 16-hour long-call admitting model on medicine teaching services amidst the new ACGME work-hour mandates. A move towards models in which teams admit daily, with non-traditional shift start and stop times (in order to mirror admitting flow from the emergency department) may be required in order to comply with the new ACGME regulations. Maintaining education and clinical volume for house staff should be a strong focus of any staffing redesign to avoid a counterproductive long term result.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the internal medicine residents for their willingness to participate in this study. There are no sources of funding to report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

References

- 1.ACGME. ACGME Outcomes Project. [Online publication.]. 1999; http://www.acgme.org. Accessed: March 12, 2012.

- 2.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedules to Improve Patient Safety., Ulmer C, Wolman DM, Johns MME. Resident duty hours : enhancing sleep, supervision, and safety. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed]

- 3.Lundberg S, Wali S, Thomas P, Cope D. Attaining resident duty hours compliance: the acute care nurse practitioners program at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center. Academic medicine : J of the Association of Am Med Colleges. 2006;81(12):1021–1025. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000246677.36103.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tessing S, Amendt A, Jennings J, Thomson J, Auger KA, Gonzalez Del Rey JA. One possible future for resident hours: interns' perspective on a one-month trial of the institute of medicine recommended duty hour limits. J of Graduate Medical Education. 2009;1(2):185–187. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00065.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, et al. Effect of reducing interns' work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1838–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gesensway D. Academic hospitalists cope with life after work-hour limits. Today's Hospitalist 2005; http://todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read&cnt=236. Accessed March 12, 2012.

- 7.Rosenbluth G, et al. Compliance With New ACGME Duty-Hour Requirements Can Improve Patient Care Measures. Journal of Hospital Medicine [Abstract]. 2011; http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Images/RIV_Image/pdf/WILEYAbstractBook2011.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2012.

- 8.Todd BA, Resnick A, Stuhlemmer R, Morris JB, Mullen J. Challenges of the 80-hour resident work rules: collaboration between surgeons and nonphysician practitioners. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84(6):1573–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrigan CP, Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Czeisler CA. Interns' compliance with accreditation council for graduate medical education work-hour limits. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1063–1070. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt KD, Miller RS, Philibert I, Heard JK, Nasca TJ. Residents' perspectives on the learning environment: data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education resident survey. Acad Med: J of the Assoc of Am Med Coll. 2010;85(3):512–518. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccc1db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arora VM, Georgitis E, Siddique J, et al. Association of workload of on-call medical interns with on-call sleep duration, shift duration, and participation in educational activities. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1146–1153. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACGME. Resident Duty Hours in the Learning and Working Environment. 2011; http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh-ComparisonTable2003v2011.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2012.

- 13.Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES., Jr The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):e3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1005800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed DA, Fletcher KE, Arora VM. Systematic review: association of shift length, protected sleep time, and night float with patient care, residents' health, and education. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(12):829–842. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antiel RM, Thompson SM, Hafferty FW, et al. Duty hour recommendations and implications for meeting the ACGME core competencies: views of residency directors. Mayo Clinic Proc Mayo Clinic Mar. 2011;86(3):185–191. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antiel RM, Thompson SM, Reed DA, et al. ACGME duty-hour recommendations - a national survey of residency program directors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbrook R. The debate over residents' work hours. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1296–1302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr022383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora VM, Seiden SC, Higa JT, Siddique J, Meltzer DO, Humphrey HJ. Effect of student duty hours policy on teaching and satisfaction of 3 rd year medical students. Am J Med. 2006;119(12):1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora V, Meltzer D. Effect of ACGME duty hours on attending physician teaching and satisfaction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1226–1228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rockey PH. Duty hours: where do we go from here? Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 2011;86(3):176–178. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher KE, Davis SQ, Underwood W, Mangrulkar RS, McMahon LF, Jr, Saint S. Systematic review: effects of resident work hours on patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):851–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers JS, Bellini LM, Morris JB, et al. Internal medicine and general surgery residents' attitudes about the ACGME duty hours regulations: a multicenter study. Acad Med: J of the Assoc of Am Med Coll. 2006;81(12):1052–1058. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000246687.03462.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuckols TK, Bhattacharya J, Wolman DM, Ulmer C, Escarce JJ. Cost implications of reduced work hours and workloads for resident physicians. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2202–2215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Nathens AB, Curtis JR. Effects of resident work hour limitations on faculty professional lives. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCoy CP, Halvorsen AJ, Loftus CG, McDonald FS, Oxentenko AS. Effect of 16-hour duty periods on patient care and resident education. Mayo Clinic Proc Mayo Clinic Mar. 2011;86(3):192–196. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Effect of residency duty-hour limits: views of key clinical faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1487–1492. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wayne DB, Arora V. Resident duty hours and the delicate balance between education and patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1120–1121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landrigan CP, Czeisler CA, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Lockley SW. Effective implementation of work-hour limits and systemic improvements. Joint Comm J on Qual and Patient Saf / Joint Comm Res. 2007;33(11 Suppl):19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine AC, Adusumilli J, Landrigan CP. Effects of reducing or eliminating resident work shifts over 16 hours: a systematic review. Sleep. 2010;33(8):1043–1053. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.8.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhavsar J, Montgomery D, Li J, et al. Impact of duty hours restrictions on quality of care and clinical outcomes. Am J Med. 2007;120(11):968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moonesinghe SR, Lowery J, Shahi N, Millen A, Beard JD. Impact of reduction in working hours for doctors in training on postgraduate medical education and patients' outcomes: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d1580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathis BR, Diers T, Hornung R, Ho M, Rouan GW. Implementing duty-hour restrictions without diminishing patient care or education: can it be done? Acad Med: J of the Assoc of Am Med Coll. 2006;81(1):68–75. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Impact of duty hour regulations on medical students' education: views of key clinical faculty. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1084–1089. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]