Abstract

We have increased organic field-effect transistor (OFET) NH3 response using tris-(pentafluorophenyl)borane (TPFB) as receptor. OFETs with this additive detect concentrations of 450 ppb v/v, with a limit of detection of 350 ppb, the highest sensitivity yet from semiconductor films; in comparison, when triphenylmethane (TPM) and triphenylborane (TFB) were used as an additive, no obvious improvement of sensitivity was observed. These OFETs also show considerable selectivity with respect to common organic vapors, and stability to storage. Furthermore, excellent memory of exposure was achieved by keeping the exposed devices in a sealed container stored at −30°C, the first such capability demonstrated with OFETs.

Ammonia (NH3) detection has received considerable attention in the fields of agricultural environmental monitoring, chemical and pharmaceutical processing, and disease diagnosis. Existing methods have limitations. For example, mass spectrometry coupled with gas chromatography (GC-MS) and optical sensors is highly sensitive and selective, but is also expensive and not easily portable, and may be unwieldy for environmental monitoring. Organic field effect transistor (OFET) sensors are proposed for gas sensing due to potential high sensitivity, low cost, low weight and potential to make flexible,1 large area or mass-produced devices. Many attempts have been made to improve NH3 transistor-based sensors. Wei et al. developed single-crystalline micro/ nanostructures of perylenediimide derivatives with a fast response rate, NH3 sensitivity of 1%, and long term stability;2 Bouvet et al. reported molecular semiconductor-doped insulator heterojunction transducers which can detect “<200 ppm” NH3 vapor;3 later, Bouvet et al. developed a novel semiconducting molecular material, Eu2[Pc(15C5)4]2[Pc(OC10H21)8] as a quasi-Langmuir-Shäfer (QLS) film as a top-layer, and vacuum-deposited and cast film of CuPc as well as copper tetra-tert-butyl phthalocyanine (CuTTBPc) QLS film as sub-layers, achieving NH3 sensitivity in the range of 15–800 ppm;4 Ju et al. used poly-3-hexylthiophene (P3HT) as semiconductor and a thermally grown SiO2/Si wafer as substrate, successfully creating a high sensitivity NH3 sensor with a detect limitation of 10 ppm;5 Zan et al. developed pentacene based organic thin-film transistors which use UV treated PMMA [poly(methyl methacrylate)] as the buffer layer to modify a SiO2 dielectric surface, and these sensors can respond to “0.5 ppm” NH3;6 later, a novel hybrid gas sensor based on amorphous indium gallium zinc oxide thin-film transistors was developed by the same group, which can respond to “0.1 ppm” NH3.7 These latter detection limits are placed in quotes because in these experiments, the ppm concentration of NH3 gas in the chamber was expressed as mg per liter of chamber volume,6 which is 1329 times higher than a more appropriate ppm definition for gas mixtures (μL/L). Therefore, the detection of trace amount of NH3 by organic field effect transistors (sub ppm v/v in the gas phase) is still challenging. Herein, we report OFET-based NH3 detectors with much higher sensitivity (0.35 ppm v/v) than previously reported. We also demonstrate the enhancement conferred by tris(pentfluorophenyl) borane (TPFB) as an NH3 receptor,8 and the ability to store the exposed detector for later electronic assessment.

Boranes have frequently acted as complexation agents for Lewis bases9–13 due to the strong interaction between boron atoms and lone pairs; furthermore, borane-amine complexes were also widely used as light-emitting molecules14 and in fluorescent sensors.15 TPFB is frequently used as a strongly Lewis acidic co-catalyst in numerous reactions, such as dehydration,16 Friedel-Crafts reactions, 17 ring-opening reactions,18 and syndiospecific living polymerization.19 Here, TPFB was chosen as the NH3 receptor additive to the OFET semiconductors due to the strong interaction between boron atoms and nitrogen atoms20 and the known vacuum sublimability of TPFB. Furthermore, the hydrogen bonds formed between hydrogen and fluorine atoms also play a role in the complexation process, with the NH3 molecule tightly bound to TPFB through all its four atoms (Scheme 1).

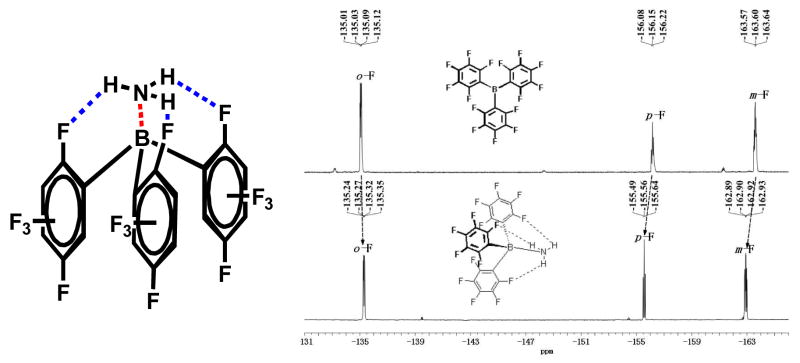

Scheme 1.

NH3-tris (pentflurophenyl) borane interaction; 19F NMR spectra of tris (pentflurophenyl) borane and borane NH3 complex. (blue bonds: hydrogen bonding, red bonds: B-N interaction)

The strong interaction between NH3 and TPFB is also confirmed by previous reports20, 21 as well as the experiments described in the supporting information (Figure S1). A proposed structure of the precipitate is shown in Scheme 1, one NH3 molecule forming a complex with one TPFB molecule through B-N interaction and three hydrogen bonds. The structure is confirmed by 19F NMR and Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) spectra. These spectra agree with previous literature data.20, 21

We used two OFET semiconductors, copper phthalocyanine (CuPc) and cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc). As TPFB controls, triphenylmethane (TPM) and triphenyl-borane (TPB) were used as additives due to their similar molecular shapes with TPFB. All OFETs were fabricated and characterized using standard methods. Materials were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Highly n-doped <100> silicon wafers with 300 nm thermally grown oxide were diced into 1 in. by 1 in. substrates, cleaned with piranha solution (Caution--corrosive!), sonicated in acetone and isopropanol, and then dried by forced nitrogen gas. Substrates were further dried by 100 °C vacuum annealing for 20 minutes prior to a 2-hour exposure to hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) vapor at 110 °C in a loosely sealed vessel. Organic semiconductors (OSCs, CuPc and CoPc) were thermally evaporated neatly or co-evaporated with TPFB, TBP, or TPM directly onto HMDS-treated substrates with a thickness of 6 nm at a rate of 0.3 Ǻ /s for the OSCs, while the deposition rate of additive was 0.2 Ǻ/s. Gold electrodes (50 nm) were thermally vapor-deposited through a mask (channel width/length (W/L) 32) at 0.3 Ǻ/s. The deposition chamber pressure was <5×10−6 torr, and substrate temperature during the deposition was held constant at 25 °C. OSC-containing film compositions were examined by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS); the results are shown in Figure S2. Fluorine element peaks (between 680 and 700) are seen in the spectra of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB, while no fluoride element peak appears in the spectra of CuPc and CoPc. All the OFETs were measured using an Agilent 4155C semiconductor analyzer. NH3 gas with a certified dilution (4.5 ppm in nitrogen) was purchased from PRAXAIR; 0.45 ppm NH3 concentration was achieved by mixing the 4.5 ppm NH3 with pure nitrogen and assayed using a photoionization detector (PID) (Pho Check Tiger, Ion Science, UK). A sealed exposure chamber with a volume of 4 liters was used, with a rotating fan inside to create a uniform vapor concentration; the flow rate of gas through the chamber was 0.2 liters per minute.

Typical OFET transfer/output curves of CuPc and CoPc with and without additives are shown in Figure S3 (drain voltage Vds = −60 V) and Figure S4, respectively. Mobilities, threshold voltages and on-off current ratios of these transistors are summarized in Table S2. OFETs with TPFB as additive show lower mobility and require higher gate voltage to turn on than the other OFETs. One possible reason may be that TPFB contains many more locally dipolar bonds than TPM and TPB, which makes it more likely for TPFB to trap holes in the channel, thus giving lower mobility and lower threshold voltage.

The responses of these devices to NH3 vapor were investigated; the percentage of drain current change I/Io (gate voltage Vg = −60 V, Vds = −60 V) are all plotted with respect to time of exposure to NH3 vapor. For some p-type semiconductors, such as CuPc, CoPc, 6PTTP6, and pentacene,22–25 the OFET current is known to be higher in dry air due to oxygen doping than in nitrogen, the carrier gas used for NH3. In order to obtain accurate and reproducible responses to NH3, all devices were subjected to ambient aging for 3 days before NH3 exposure experiments. The responses shown in the following figures are corrected for the current decrease caused by replacing oxygen with nitrogen.

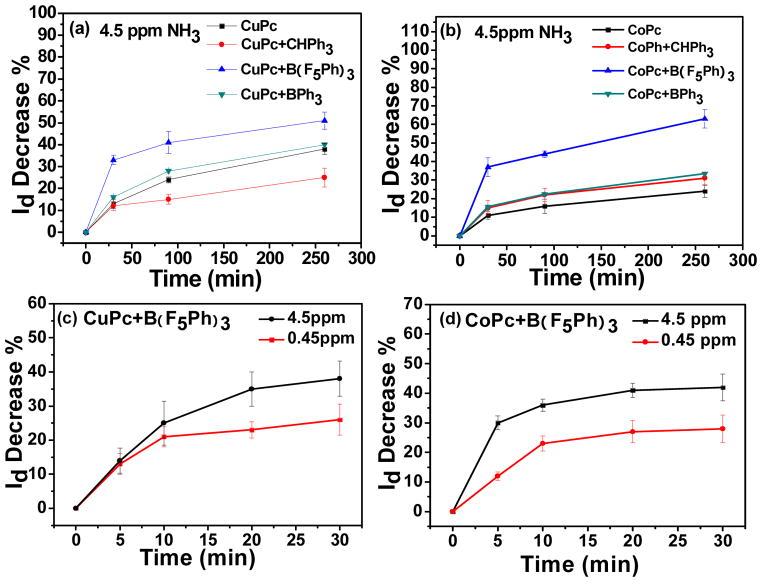

As shown in Figure 1(a) and (b), after exposure to 4.5 ppm NH3 vapor for 30 minutes, the drain current of CuPc, CuPc&TPM and CuPc&TPB decreased 13%, 12% and 16% respectively. For CuPc&TPFB, the decrease in drain current was 33%, which is much higher than the responses of CuPc, CuPc&TPM and CuPc&TPB. For CoPc, CoPc&TPM and CoPc&TPB, the decrease was 11%, 15% and 16% respectively, and for CoPc&TPFB, the decrease was 37%, which is also much higher than for CoPc, CoPc&TPM and CoPc&TPB. This larger decrease is consistent with the strong interaction between TPFB and NH3 vapor increasing the binding of NH3 to the semi-conductor surface, thus giving a much higher relative response. While TPM has a similar molecular structure as TPFB, it has no host-guest interaction with NH3, and the enhancement in relative response was not obtained. Although TPB has a boron atom in the molecular center, it is a much weaker lewis acid compared to TPFB, 26 moreover, there is no hydrogen bonding between TPB and NH3, therefore, the response is also much lower than the response of TPFB. After 90 minutes of exposure, the decreases in drain current of CuPc, CuPc&TPM, CuPc&TPB and CuPc&TPFB were 24%, 15%, 28% and 41% respectively. For CoPc, CoPc&TPM, CoPc&TPB and CoPc&TPFB, the decreases were 16%, 22%, 23% and 44%, respectively. After 260 minutes of exposure, the drain current of CuPc, CuPc&TPM, CuPc&TPB and CuPc&TPFB decreased by 38%, 25%, 40% and 51% respectively. For CoPc, CoPc&TPM, CoPc&TPB and CoPc&TPFB, the drain current decreased by 24%, 31%, 33% and 63% respectively. Over time, the rate of drain current decrease became lower. A listing of the numbers of different evaporations, wafers and devices used in this study is summarized in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Drain current decrease of (a) CuPc, CuPc&TPM, CuPc&TPFB and CuPc&TPB devices and (b) CoPc, CoPc&TPM, CoPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPB devices after different times of exposure to 4.5 ppm NH3; Drain current decrease of (c) CuPc&TPFB device and (d) CoPc&TPFB device after different times of exposure to 4.5 ppm and 0.45 ppm NH3 vapor.

Sensing cycle experiments were also done (Figure S5). In this set of experiments, NH3 exposure time is 90 seconds, the devices give instant responses, and recover immediately after airflow over the devices’ surface. The recovery takes a relatively long time only when the responses are high (>30%). Within the range of concentrations measured (0.45 ppm–20 ppm), we observe a relatively linear change in response. Therefore, the devices give an instantaneous response and reflect the real concentration of the analyte in the air. At later stages, the system works according to an accumulative model.

In a third set of experiments, CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB were exposed to a much lower NH3 concentration (0.45 ppm in nitrogen), and the results are shown in Figures 1(c) and (d). After 5 minutes’ exposure, the drain current of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB decreased by 13% and 12% respectively, while after 10 minutes, the drain currents decreased by 21% and 23%; after 20 and 30 minutes exposure, the drain current of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB decreased 23% and 26%, and 27% and 28% respectively. In comparison, responses of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB to 4.5 ppm NH3 after 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes are also shown in Figures 1(c) and (d). While the higher concentration gives greater response, the time for equilibration may be increased because of barriers to NH3 reaching some of the sites complexed with higher concentrations. Additionally, we have also exposed the device to 0.35 ppm and 0.25 ppm NH3, the results were summarized in Table S3. According to the definition of limit of detection25, 27 (LOD =Rblank + 3S; “Rblank” is blank response, “S” is standard deviation of response), we get a conservative estimate value of limit of detection is 0.35 ppm.

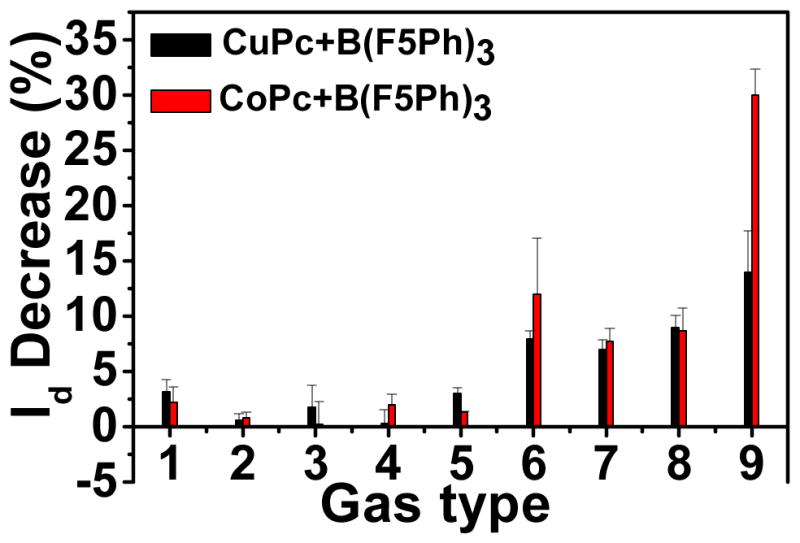

The selectivity of these devices was also investigated. Figure 2 displays the drain current change of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB after exposure to different gas vapors. Methanol, acetone and ethyl acetate were chosen due to oxygen interactions with TPFB between O and B atoms.28 Dichloromethane is a highly volatile solvent, it may exist in some circumstances at high concentration, so it is desirable to check this vapor. As shown in figure 2, all these solvents give only small responses even at very high concentrations (several thousands ppm). The devices are also stable to high hydrogen concentration. It is not surprising that these devices are sensitive to volatile amines; however, the responses are smaller than the response to NH3 (4.5ppm NH3 vs 10ppm isopropylamine or 10ppm isobutylamine).8 The possible reason may be the alkyl chain of the amines causing steric hindrance while binding with TPFB, resulting in a relatively longer B-N bond than that of NH3,20 thus give lower responses than NH3. Another reason may be one TPFB molecule can bind with two NH3 molecules,20 while there is no prior report that one TPFB can bind with two amine molecules; so TPFB is more sensitive and efficient to detect NH3 vapor than organic amine vapors. For H2S, these devices also show relatively high responses, however, the responses are also lower than the responses of NH3. Furthermore, H2S is an acidic gas, while NH3 is basic gas. Due to their significantly different properties, it is easy to selectively filter H2S with basic powder, the same method used in some previous literature.29, 30 These devices also shown good stablity to moisture, the drain current can maintain above 50% of its original value even after 7days exposures to lower than 30% relative humidity (RH) at 25 °C; only when the RH is higher than 50%, the devices show relative fast linear decay (Figure S6). Water is also filterable from NH3, using a highly basic dessicant.

Figure 2.

Drain current change of CuPc&TPFB and CoPc&TPFB devices in different gas vapor for 5 minutes; 1, methanol (2000 ppm); 2, acetone (1800 ppm); 3, dichloromethane (3900 ppm); 4, ethyl acetate (1500 ppm); 5, 5% H2 (50000 ppm); 6, isopropylamine (10ppm); 7, isobutylamine (10ppm); 8, H2S (5ppm); 9, NH3(4.5ppm).

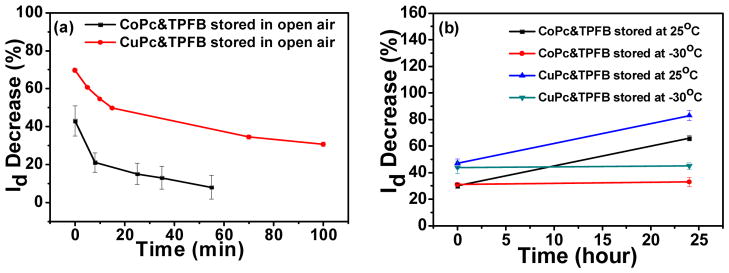

Retention of the exposure effect is important if reading the device right after exposure is impractical. Diffusion of the analyte out of the device or even within the device must be prevented. Maintaining the NH3-exposed device in open air, or in a sealed, air-filled container (1″ diameter Fluoroware) at room temperature, was insufficient to keep the post-exposure current constant. However, by placing the exposed devices in the container and storing at low temperature (−30 °C), the signal change after one day is small. As shown in Figure 3, for CuPc&TPFB, an exposed device with a response of 70% drain current decrease gradually lost its response signal while stored in open air; the device stored in the container at 25 °C showed a signal change from 47% to 83% after 24 hours, perhaps because of NH3 diffusion within the device to more electronically active sites. However, for the device stored in the container at −30 °C, the signal only showed an insignificant change after 24 hours, from 44% to 45%. For CoPc&TPFB, the device stored in open air also lost its signal and recovered eventually; the device stored in the container at 25 °C showed a signal change from 30% to 66% after 24 hours; while for the device stored in the container at −30 °C, the signal showed a negligible change, from 31% to 33%. The change after one day of storage in the container at −30 °C is less than 3% of the original current, and invariably less than 6% of the original current, even for responsive current changes >50%. Drain current change after 24 hours at other storage temperatures is shown in Figure S7.

Figure 3.

Current change of differently stored devices.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a highly responsive NH3 detector using TPFB as a receptor. OFETs using this additive can detect concentrations at least as low as 450 ppb v/v, and with a LOD value of 0.35 ppm. In comparison, when TPM and TPB were used as additives, no obvious improvement in sensitivity was observed. The specific host-guest interaction between NH3 and TPFB appears to be critical for the enhancement observed relative to neat semiconductors. Additionally, these OFETs also show good selectivity and storage stability. Device current changes were preserved by keeping the devices in a sealed container stored at −30° C. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of using borane as a receptor in a sensitive organic field effect transistor, the first use of OFETs to record responses to vapors, and the most sensitive semiconductor-based NH3 detection demonstrated to date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jasmine Sinha for help with editing. We are grateful to JHSPH Center for a Livable Future, NIEHS Center in Urban Environmental Health - P30 ES 03819, and Johns Hopkins Environment, Energy, Sustainability & Health Institute for support of this work.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Experimental details about NH3 and TPFB interaction, XPS data, typical transfer curves and output curves of CuPc and CoPc with and without additives, ATR and 19F NMR spectra of TPFB-NH3 complex, humidity experiment, sensing cycle data, determination of LOD experiments, memory behavior at different storage temperatures and a table of samples investigated are available in supporting information. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.a) Mabeck JT, Malliaras GG. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;384:343. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Torsi L, Dodabalapur A, Sabbatini L, Zambonin PG. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2000;67:312. [Google Scholar]; c) Crone B, Dodabalapur A, Gelperin A, Torsi L, Katz HE, Lovinger AJ, Bao Z. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;78:2229. [Google Scholar]; d) See KC, Becknell A, Miragliotta J, Katz HE. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3322. [Google Scholar]; e) Huang J, Dawidczyk TJ, Jung BJ, Sun J, Mason AF, Katz HE. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:2644. [Google Scholar]; f) Someya T, Dodabalapur A, Huang J, See KC, Katz HE. Adv Mater. 2010;22:3799. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Huang J, Sun J, Katz HE. Adv Mater. 2008;20:2567. [Google Scholar]; h) Huang J, Miragliotta J, Becknell A, Katz HE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9366. doi: 10.1021/ja068964z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Hammock ML, Sokolov AN, Stoltenberg RM, Naab BD, Bao ZN. ACS Nano. 2012;6:3100. doi: 10.1021/nn204830b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Khan HU, Roberts ME, Knoll W, Bao ZN. Chem Mater. 2011;23:1946. [Google Scholar]; k) Roberts ME, LeMieux MC, Bao ZN. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3287. doi: 10.1021/nn900808b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Torsi L, Farinala GM, Marinelli F, Tanese MC, Omar OH, Valli L, Babudri F, Palmisano F, Zambonin PG, Naso F. Nat Mater. 2008;7:412. doi: 10.1038/nmat2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Kim C, Wang ZM, Choi HJ, Ha YG, Facchetti A, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6867. doi: 10.1021/ja801047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang YW, Fu L, Zou WJ, Zhang FL, Wei ZX. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:10399. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet M, Xiong H, Parra V. Sensors Actuat B-Chem. 2010;146:501. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YL, Bouvet M, Sizun T, Barochi G, Rossignol J, Lesniewska E. Sensors Actuat B-Chem. 2011;155:165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong JW, Lee YD, Kim YM, Park YW, Choi JH, Park TH, Soo CD, Won SM, Han IK, Ju BK. Sensors Actuat B-Chem. 2010;146:40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zan H-W, Tsai W-W, Lo Y-r, Wu Y-M, Yang Y-S. IEEE Sensors J. 2012;12:594. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zan HW, Li CH, Yeh CC, Dai MZ, Meng HF, Tsai CC. Appl Phys Lett. 2011;98:253503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esser B, Schnorr JM, Swager TM. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:5752. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steed JW, Atwood JL. Supramolecular Chemistry. Wiley-Chichester; UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes CC, Scharn D, Mulzer J, Trauner D. Org Lett. 2002;2:4109. doi: 10.1021/ol026865u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reetz MT, Niemeyer CM, Hermes M, Goddard R. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1992;32:1017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reetz MT, Huff J, Goddard R. Tet Lett. 1994;35:2521. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carboni B, Monnier L. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:1197.See also: Huskens J, Goddard R, Reetz MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6617.Nozaki K, Tsutsumi T, Takaya H. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6668.

- 14.Goeb S, Ziessel R. Org Lett. 2007;9:737. doi: 10.1021/ol0627404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang XF, Liu XL, Lu R, Zhang HJ, Gong P. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:1167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanglee YJ, Hu J, White RE, Lee MY, Stewart SM, Perrotin P, Scott SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:355. doi: 10.1021/ja207838j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thirupathi P, Neupane LN, Lee K-H. cheminform. 2012;43 doi: 10.1002/chin.201205089. ASAP. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson IDG, Yudin AK. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5160. doi: 10.1021/jo0343578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawabe M, Murata M, Soga K. Macromol Rapid Commun. 1999;20:569. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mountford AJ, Lancaster SJ, Coles SJ, Horton PN, Hughes DL, Hursthouse MB, Light ME. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:5921. doi: 10.1021/ic050663n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massey AG, Park AJ. J Organometal Chem. 1964;2:245. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J, Royer JE, Colesniuc CN, Bohrer FI, Sharoni A, Jin S, Schuller IK, Trogler WC, Kummel AC. J Appl Phys. 2009;106:034505. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohrer FI, Sharoni A, Colesniuc CN, Park J, Schuller IK, Kummel AC, Trogler WC. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5640. doi: 10.1021/ja0689379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohrer FI, Colesniuc CN, Park J, Ruidiaz ME, Schuller IK, Kummel AC, Trogler WC. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:478. doi: 10.1021/ja803531r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohrer FI, Colesniuc CN, Park J, Schuller IK, Kummen AC, Trogler WC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3712. doi: 10.1021/ja710324f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka Y, Hasui T, Suginome M. Synlett. 2008;8:1239. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil OS. Clin Chem 45. 1999;2:165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saverio AD, Focante F, Camurati I, Resconi L, Beringhelli T, D’Alfonso G, Donghi D, Maggioni D, Mercandelli P, Sironi A. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:5030. doi: 10.1021/ic0502168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunet J, Pauly A, Mazet L, Germain JP, Bouvet M, Malezieux B. Thin Solid Films. 2005;490:28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viricelle JP, Pauly A, Mazet L, Brunet J, Bouvet M, Varenne C, Pijolat C. Mater Sci Eng C. 2006;26:186. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.