Background: Lumican, an extracellular matrix protein, promotes host response to LPS endotoxins.

Results: Lum−/− mice show increased lung infection. Phagocytosis of nonopsonized bacteria is reduced in Lum−/− macrophages and restored by recombinant wild type lumican but not mutated rLumY20A.

Conclusion: Lumican interaction with CD14 at an N-terminal tyrosine is important for bacterial phagocytosis.

Significance: A broader function is implicated for lumican and other LRR ECM proteins in host pathogen interactions.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Innate Immunity, Phagocytosis, Proteoglycan, Pseudomonas, CD14, Lumican, TLR4

Abstract

Phagocytosis is central to bacterial clearance, but the exact mechanism is incompletely understood. Here, we show a novel and critical role for lumican, the connective tissue extracellular matrix small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan, in CD14-mediated bacterial phagocytosis. In Psuedomonas aeruginosa lung infections, lumican-deficient (Lum−/−) mice failed to clear the bacterium from lungs, tissues, and showed a dramatic increase in mortality. In vitro, phagocytosis of nonopsonized Gram-negative Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa was inhibited in Lum−/− peritoneal macrophages (MΦs). Lumican co-localized with CD14, CD18, and bacteria on Lum+/+ MΦ surfaces. Using two different P. aeruginosa strains that require host CD14 (808) or CD18/CR3 (P1) for phagocytosis, we showed that lumican has a larger role in CD14-mediated phagocytosis. Recombinant lumican (rLum) restored phagocytosis in Lum−/− MΦs. Surface plasmon resonance showed specific binding of rLum to CD14 (KA = 2.15 × 106 m−1), whereas rLumY20A, and not rLumY21A, where a tyrosine in each was replaced with an alanine, showed 60-fold decreased binding. The rLumY20A variant also failed to restore phagocytosis in Lum−/− MΦs, indicating Tyr-20 to be functionally important. Thus, in addition to a structural role in connective tissues, lumican has a major protective role in Gram-negative bacterial infections, a novel function for small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycans.

Introduction

Phagocytosis is an essential step in the response of a host to a pathogen and its clearance. Several mechanisms, independently and collaboratively, support phagocytosis of microbes. Most studies of innate immune response and phagocytosis focus on host receptors and cytoplasmic regulators. However, the extracellular matrix (ECM)3 comes in close contact with phagocytes and provides a scaffold for integrin-mediated adhesion and migration of inflammatory cells (1–3), yet functions of specific ECM proteins in innate immune response and phagocytosis are unclear. Phagocytosis of serum-opsonized bacteria is mediated by the Fcγ- and complement receptors present on the surface of phagocytes binding to IgG and complement molecules, coating the microbe. Phagocytosis of nonopsonized bacteria is enabled by direct interactions of phagocyte cell surface receptors such as scavenger receptor members, lectins and CD14 with the bacterial cell wall (4). CD14 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked 55-kDa glycoprotein on the surfaces of monocytes and neutrophils. It promotes host response to bacterial peptidoglycans and LPS via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (5–8).

Lumican (Lum), a component of the interstitial ECM, is emerging as a regulator of host-pathogen interactions. Lumican is a member of the small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan (SLRP) family (9) and is best known for its interactions with fibrillar collagens (10). We first investigated gene-targeted lumican-deficient (Lum−/−) mice for connective tissue abnormalities and found altered collagen fibril structures in the cornea, tendon, and other connective tissues with a loss of corneal transparency, skin fragility, and biomechanically weak tendons (11–13). The presence of leucine-rich repeat motifs in the lumican core protein and its structural similarities with the leucine-rich repeat superfamily members, CD14 and the TLRs (14), prompted us to investigate functions of lumican in innate immunity. The Lum−/− mice were partially resistant to LPS-mediated septic shock, with subnormal levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines. Moreover, the Lum−/− macrophages (MΦ) showed poor induction of proinflammatory cytokines after LPS stimulation in vitro, whereas their response to other pathogen-associated molecular patterns were not inhibited (15). Specific binding between lumican and CD14 was indicated by co-immunoprecipitation of lumican and CD14 from elicited peritoneal MΦs and in pulldown assays using a mammalian expression system. In a solid phase binding assay, lumican bound LPS that could be competed out with soluble recombinant CD14. These in vitro findings, taken together with the hypo-responseness of Lum−/− mice to LPS septic shock, prompted us to hypothesize that bacterial infections may have a contrary negative effect in the absence of lumican.

Here, we show that Lum−/− mice are unable to clear Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a lung infection model with a marked increase in mortality and morbidity. Lumican associates with bacteria on the surface of primary peritoneal MΦs and regulates phagocytosis mediated by CD14. We further characterized the lumican-CD14 binding by surface plasmon resonance; substitution of an N-terminal tyrosine (rLumY20A) in lumican led to its rapid dissociation from CD14. Using lumican and lumican-CD14 double-null mouse MΦs, we determined that lumican regulates bacterial ingestion, whereas CD14 is needed for phagosome progression to late endosomes. This study provides mechanistic and molecular insights into how an ECM protein regulates CD14-dependent phagocytosis and clearance of Gram-negative bacteria in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant Proteins, Antibodies, and Reagents

Recombinant human lumican (rLum) was prepared by cloning a lumican construct intio the pSecTag2A vector and expressing the protein in HEK293 cells (16). The recombinant proteins carry a His6 tag and were purified by a His affinity column chromatography. Two lumican mutations (rLum-Y20A and rLum-Y21A) were created by PCR mutagenesis (Table 1), and the parental methylated plasmid DNA was removed by Dpn I restriction digestion. The rLum and mutated rLum preparations were tested for biological activity by determining their effects on in vitro collagen fibrillogenesis kinetics. Antibodies against mouse and human lumican were custom-made by Covance Research Products. The following antibodies and recombinant proteins were purchased: human CD14 (R & D Systems), biotinylated monoclonal anti-CD14, anti-CD18, and APC-conjugated F4/80 (BD Biosciences), Gr1-FITC (eBioscience), LysoTracker® Red DND-99, Alexa Fluor® 532 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor® 594-streptavidin conjugate, Alexa Fluor® 647 goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen), CD11b-FITC, CD38-PE (BD Pharmingen), CD40-FITC, CD206-PE (Biolegend), CD80-FITC, CD86-FITC (eBioscience), CD204-FITC (Pierce), and anti-Na/K-ATPase (Novus Biological). For blocking phagocytosis, we used a rat anti-mouse CD18 (555280; BD Pharmingen) and anti-human CD14 (MA B3832; R & D Systems).

TABLE 1.

Recombinant lumican variants by PCR mutagenesis

| Mutant | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| rLumY20A | Forward | 5′-GCGGCCCAGCCGGCCGCCTATGATTATGAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGCCGGCTGGGCCGCGTCACCAGTGGAAC-3′ | |

| rLumY21A | Forward | 5′-GCCCAGCCGGCCTACGCTGATTATGATTTTCC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTAGGCCGGCTGGGCCGCGTCACCAGTGG-3′ |

Mice and Bacterial Strains

The Lum−/− mice generated earlier (11) were backcrossed to the C57BL/6J background for more than 12 generations. Lum−/−CD14−/− double null mice were generated by breeding the Lum−/− with CD14−/−/C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory). C57BL/6J WT and the knock-out mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free mouse facility at the Johns Hopkins University and used according to the institutional animal care and use committee. Mice between the ages of 8–9 weeks were used in all experiments, and the animals were gender-balanced within an experiment. P. aeruginosa (ATCC, 19660) was used to develop the murine lung infection model. GFP-expressing P. aeruginosa (GFP-PAO1) was gifted by Dr. Suzanne Fleiszig (University of California, Berkeley). P. aeruginosa strains 808 and P1 were gifted by Dr. David Speert (University of British Columbia and British Columbia Children's Hospital). All of the P. aeruginosa strains were grown overnight in Difco nutrient broth at 37 °C, subcultured the next day till they reached mid-log phase, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and resuspended in PBS or Hanks' balanced salt solution for further use. The following were purchased from Invitrogen: pHrodoTM Escherichia coli BioParticles®, Alexa Fluor® 488 E. coli BioParticles® conjugates (Alexa 488 E. coli), and Alexa Fluor® 488 Staphylococcus aureus BioParticles® conjugates (Alexa 488 S. aureus).

Peritoneal MΦ Isolation and Culture

Peritoneal MΦs were harvested from peritoneal exudates 4 days after an intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml of 3% thioglycolate. The cells were plated in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 1% FBS. After overnight incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the attached MΦs were washed three times with PBS, switched to serum-free RPMI, and used for all assays. By flow cytometry, more than 98% of the cells were F4/80 positive (data not shown).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Peritoneal MΦs were treated with or without 10 ng/ml of ultrapure E. coli LPS (0111:B4, List Biological Laboratories) for 2 h. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The expression of lumican, biglycan (Bgn), decorin (Dcn), fibromodulin (Fmod), and Gapdh was determined by quantitative RT-PCR following standard protocols using the iQTMSYBR Green Supermix kit (Bio-Rad). The following forward and reverse primers were used: Lum, 5′-TCGAGCTTGATCTCTCCTAT-3′ and 5′-TGGTCCCAGGATCTTACAGAA-3′; Fmod, 5′-TCCAGGGCAACAGGATCAATGAGTT-3′ and 5′-TGCGCTGCGCTTGATCTCGT-3′; Dcn, 5′-TCTTGGGCTGGACCATTTGAA-3′ and 5′-CATCGGTAGGGGCACATAGA-3′; and Bgn, 5′-GCACCTCTACGCCCTGGTCTTG-3′ and 5′-TCCGCAGAGGGCTAAAGGCCT-3′. For PCR amplification, we used 40 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 58 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (1 min) in an Applied Biosystems 7900HT, and the SDS v2.3 software was used to analyze detection threshold cycles.

Phagocytosis

MΦs (2.0 × 105 cells/well) were incubated with 6 × 106 of pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and time lapse live cell images were acquired every 2 min, five frames of z-stacking with 2-μm optic slice by Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscopy fitted with 63×/1.2 water objective at 37 °C, 5% CO2. On average 150–300 MΦs were analyzed to determine mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) from pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® using the Image J software, and the data were expressed as MFI/MΦ.

Bacterial association with the cell surface was determined using Alexa Fluor® 488 E. coli BioParticles® conjugates or GFP-P. aeruginosa PAO1, where MΦs were first incubated at 37 °C for 20 min with bacteria and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The plasma membrane was immunostained with an antibody against Na/K-ATPase, nuclei with DAPI, while lumican, and CD14 and CD18 localized by immunostaining as previously described (17), and images were captured with an oil objective of 40×/1.3 or 100×/1.4 in a Zeiss LSM 410 microscope.

To determine bound and ingested P. aeruginosa ATCC19660 strain, MΦs from WT and Lum−/− mice were incubated with bacteria (13/MΦ) at 4 °C and 37 °C for 1 and 2 h. The MΦs were centrifuged, washed in PBS (3×), and lysed in water, and serial dilutions were plated on Pseudomonas selective Cetrimide Agar (Sigma-Aldrich) to obtain viable cfu.

Localization of Bacteria in Late Endosome/Lysosome

We incubated MΦs with Alexa 488 E. coli for 30 min, and the lysosomal compartment was stained with 100 nm LysoTracker® Red DND-99 for another 30 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in serum-free RPMI. Time lapse images were acquired every 3 min in the 30–60-min period. Areas of overlaps (yellow) between bacteria (green) and lysosomes (red) were calculated using Image J for three Alexa-E. coli particles per experiment. In a second approach, MΦs were incubated with Alexa 488 E. coli for 40, 60, and 90 min; fixed; and immunostained with anti-mouse CD107 (LAMP-1) antibody.

Bacterial Killing

MΦs were incubated with P. aeruginosa ATCC19660 (13 bacteria/MΦ) in 1 ml of serum-free RPMI with gentle shaking for 1 and 2 h. The macrophages were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times in PBS, and resuspended in water to lyse the cells. Serial dilutions of the supernatant and lysed cells were plated for cell-associated viable cfu.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Human recombinant CD14 (Abcam) was immobilized on a CM5 (carboxymethylated) sensorchip (GE Healthcare) by injecting 50 μl of CD14 (25 μg/ml in 10 mm sodium acetate, pH 4.5) at the rate of 10 μl/min. Blank channels without CD14 served as controls. Between injections, the CD14 immobilized sensorchip was washed with 0.01% SDS and degassed phosphate-buffered saline. The rate constants of association and dissociation were derived at eight different injection concentrations of positive, negative control, and test analytes. The analytes were injected for 1.5 min at 25 μl/min with a dissociation interval of 5 min. The differences in the reference and blank cell readings were used to determine specific binding. When anti-CD14 IgG was used as the analyte, the cells were regenerated by washing with 10 mm glycine, pH 2.0, for 30 s. The dissociation constant (KD) was calculated from the sensorgram data by fitting a 1:1 Langmuir model using the BIA evaluation 4.1 software (BIAcore; GE Healthcare).

Mouse Model of Lung Infection

Anesthetized mice (Avertin, 350 mg/kg of body weight) were infected by intranasal or intratracheal delivery of 108 cfu of P. aeruginosa (ATCC 19660). The mice were harvested 12 and 20 h after infection, and the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected by tracheal intubation. Lung tissues for histology were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded for hematoxylin and Periodic-acid Schiff staining. Frozen lung tissue sections (5 μm) were incubated overnight with Gr1-FITC diluted in 1% FBS/phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20, and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (eBioscience) and washed in phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 and mounted in fluorescent mounting media (Dako). To assess viable bacteria, lung tissues were weighed and homogenized with 5 μl of PBS/μg of tissue, and appropriate dilutions were plated on agar and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Statistical Analysis

The experiments were repeated two or three times as indicated in the figure legend. Statistical significance was calculated using unpaired Student's t test (Graphpad Prism), and p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Lumican Regulates Phagocytosis by MΦs

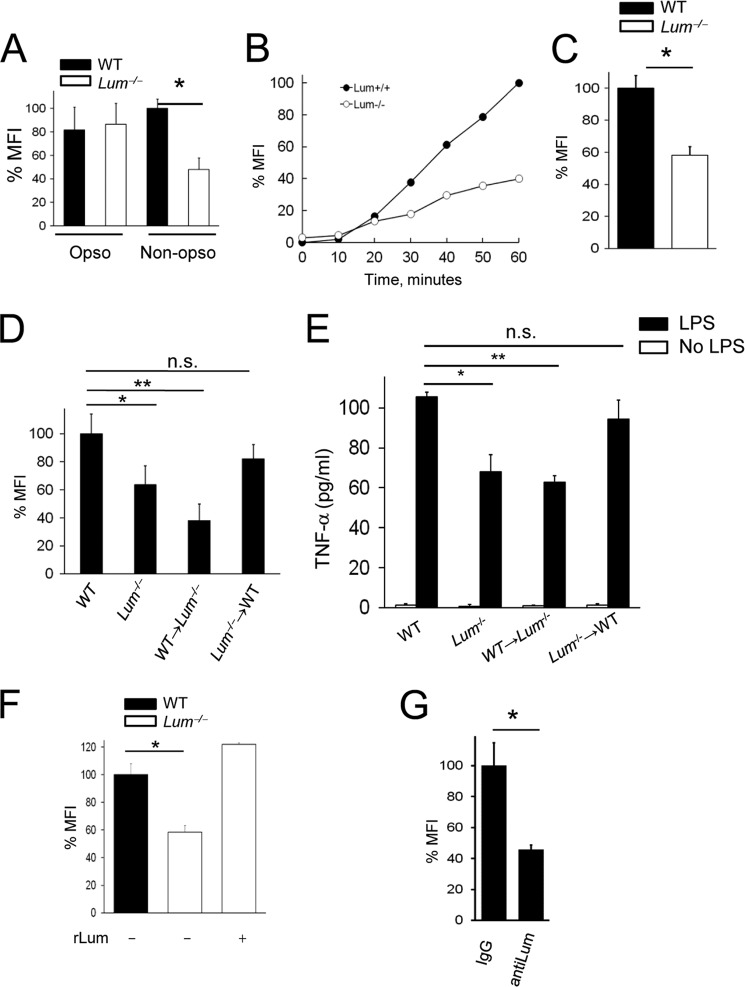

Our previous studies indicated a role for lumican in CD14-TLR4 mediated innate immune response to LPS (15, 17). To further investigate its implications in host response to bacteria, we determined the uptake of pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® by elicited peritoneal MΦs. The pHrodoTM dye increases in fluorescence in a pH-dependent manner as the BioParticles® reach the acidic lysosomal compartments, and acidification of phagosomes can be measured as MFI per MΦ. We first compared phagocytosis of opsonized and nonopsonized E. coli in WT and Lum−/− MΦs to distinguish between phagocytosis mediated by host receptors such as Fcγ and complement receptors versus those that do not require opsonization of the pathogen. After 1 h, phagocytosis of serum-opsonized E. coli occurred unhampered, whereas that of nonopsonized E. coli was reduced by 52% in the Lum−/− MΦs (Fig. 1A). Thus, lumican does not seem to modulate phagocytosis of serum-opsonized bacteria, and subsequent assays were carried out in serum-free medium. We examined phagosome acidification by time lapse imaging over 1 h, and bacterial uptake was evident in the WT but impaired in the Lum−/− MΦs (Fig. 1B). On average, phagosome acidification after 60 min (Fig. 1C) was 43% lower in the Lum−/− compared with wild type MΦs.

FIGURE 1.

Phagosome acidification impaired in Lum−/− MΦs. WT and Lum−/− peritoneal MΦs were incubated with pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® for 60 min (30 bacteria/MΦ). Phagocytosis was measured as MFI normalized for 150–300 MΦ per field and expressed as percentages of WT in all the experiments. A, phagocytosis of nonopsonized bacteria was lower in Lum−/− compared with WT. *, p < 0.01. Nonopsonized bacteria were used in the remaining assays. Opso, opsonized; Non-opso, nonopsonized. B, quantitative representation of phagocytosis from time lapse images. C, average MFI/MΦ from three low magnification fields after 1 h. *, p < 0.002. D, phagocytosis in BMC was significantly reduced in Lum+/+ → Lum−/−, but normal in Lum−/− → Lum+/+ MΦs. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005. E, induction of TNF-α in BMC MΦs; ELISA of TNF-α from the medium of 105 attached MΦs induced with 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h. F, rLum restored phagocytosis in Lum−/− MΦs. *, p < 0.002. G, phagocytosis in WT MΦs measured after treatment with 5 μg/ml of anti-lumican antibody or IgG. *, p < 0.002. The data are the means ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of two independent experiments (A-C, F, and G). n.s., not significant.

Although lumican contributed to MΦ functions, we did not detect lumican transcript in MΦs by quantitative RT-PCR (Table 2), confirming our previous observation (15). Therefore, we hypothesized that exogenous lumican is acquired by MΦs for optimal phagocytosis. We also found other SLRP members, decorin and biglycan, and not fibromodulin, to be expressed by MΦs (Table 2). We excluded intrinsic developmental differences as factors influencing phagocytosis, by flow cytometric analyses of cell surface markers in peritoneal exudate F4/80+ WT and Lum−/− MΦs that showed similar differentiation markers and surface TLR2 (supplemental Fig. S1). However, there was a 2-fold decrease in TLR4 in the Lum−/− MΦs, consistent with our previously identified link between lumican and TLR4 signaling (15, 17). We next developed bone marrow cell chimeras (BMC), which by FACS typing of CD45 had greater than 85% donor contribution (data not shown). MΦs from Lum−/− donor in WT recipient (Lum−/− → WT) BMC showed wild type-like phagocytic capabilities, whereas MΦs from WT → Lum−/− BMC were phagocytosis deficient, like the parental Lum−/− mice (Fig. 1D). We also tested induction of TNF-α by LPS as a measure of innate immune response in the BMC MΦs; Lum−/− → WT showed WT like response, whereas WT → Lum−/− BMC showed poor induction of TNF-α (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, in in vitro assays, exogenous rLum restored phagocytic functions of the Lum−/− MΦs (Fig. 1F), whereas antibody-mediated blocking of lumican in WT MΦs inhibited phagocytosis (Fig. 1G), supporting a role for lumican in phagocytosis. Immunofluorescent staining for lumican in WT MΦs, without permeabilizing the cells, showed its presence on the surface (supplemental Fig. S2), corroborating our study and earlier studies of others showing lumican binding to macrophages (15, 18). We also found that lumican is expressed in mouse lung tissues and in culture by HUVECs and fibroblasts (16, 17, 19), and others have shown its presence in the vascular endothelial ECM (20, 21). Our earlier study showed the presence of lumican on mouse peritoneal neutrophils. Thus, the cell surface lumican on MΦs is likely to be acquired from the ECM during their transport.

TABLE 2.

MΦ expression of lumican, fibromodulin, decorin, and biglycan

| Average Ct values |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lum | Fmod | Bgn | Dcn | Gapdh | |

| Control | Ub | U | 28.16 ± 0.07 | 23.59 ± 0.10 | 15.94 ± 0.03 |

| LPSa | U | U | 30.63 ± 0.04 | 24.33 ± 0.29 | 18.51 ± 0.07 |

a 10 ng/ml LPS for 2 h.

b U, undetected.

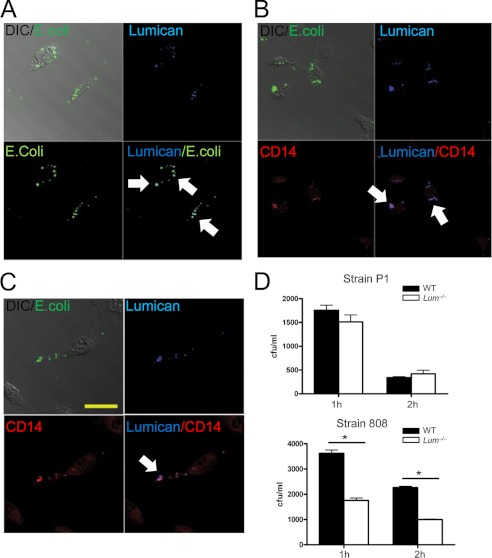

Lumican Facilitates CD14-dependent Phagocytosis

Because our previous studies showed binding of lumican to CD14 and CD18 by immunoprecipitations (15, 17), here we sought to determine whether lumican co-localizes with CD14, CD18, and bacteria on MΦ surfaces during phagocytosis. WT MΦs were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 E. coli BioParticles® conjugates (Alexa 488 E. coli) and immunostained for lumican, CD14, and CD18; overlapping staining patterns for lumican, bacteria, CD14, and CD18 were detected (Fig. 2, A–C).

FIGURE 2.

Lumican co-localizes with CD14, CD18, and E. coli on MΦ surfaces. A–C, WT MΦs incubated with Alexa 488 E. coli for 1 h, permeabilized, and immunostained for lumican (blue), CD14 (red), and CD18 (red). Lumican co-localized with E. coli, CD14, and CD18. Scale bar, 20 μm. D, P. aeruginosa strains P1 and 808 in mid-log phase were incubated with MΦs (13 bacteria/MΦ) at 4 and 37 °C for 1 and 2 h. The results represent cell-associated bacteria at 4 °C subtracted from 37 °C from triplicate wells ± S.D. *, p ≤ 0.025; **, p ≤ 0.005.

We next tested the role of lumican in CD14- and CD18-mediated phagocytosis using two different P. aeruginosa strains with differential host receptor bias. The P1 strain has a CR3 (β2 or CD18) receptor bias, whereas the 808 strain is taken up by CD14-mediated phagocytosis (22). Because Lum−/− MΦs were fully capable of engulfing serum-opsonized bacteria (Fig. 1A), we envisioned CD18, a complement component 3 receptor subunit, to have lumican-independent phagocytic functions. Consistent with this idea, phagocytosis of the P1 strain (CD18-dependent) was reduced slightly, whereas that of the 808 strain (CD14-dependent) was reduced significantly in Lum−/− MΦs after 1 and 2 h of incubation at 37 °C (p = 0.0006 and p = 0.0005) (Fig. 2D), indicating that lumican functions in CD14-regulated phagocytosis primarily. We further tested this using pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® and WT MΦs after antibody-mediated blocking of either CD14 or CD18 (supplemental Fig. S3). Lum−/− MΦs were susceptible to anti-CD18-mediated inhibition of phagocytosis (p < 0.01), indicating CD18 phagocytosis to be operative, even in the absence of lumican. By contrast, anti-CD14 caused very little additional blockade of phagocytosis in the Lum−/− MΦs (p = 0.07), indicating low CD14 phagocytic activities in the absence of lumican.

Bacterial Uptake Reduced in Lum−/− MΦs

To investigate how lumican and CD14 cooperate in phagocytosis, we broke down overall phagocytosis into two stages: initial bacterial uptake and formation of phagosomes and a later stage where bacteria appear in late endosomes and lysosomes. In actuality, this is a multistage process. To test whether initial bacterial uptake is aided by lumican, WT and Lum−/− MΦs were incubated for 20 min with Alexa 488 E. coli, fixed without permeabilization, and immunostained for Na/K-ATPase as a membrane marker. The Lum−/− MΦs had fewer plasma membrane-associated bacteria compared with WT. However, bacterial association with CD14−/− MΦs, which are wild type for lumican, was normal and may be even higher (Fig. 3, A and B). This may be because progression of the early phagosomes to late endosomes is delayed in CD14 deficiency; more bacteria can be seen at the cell surface at any one time. The Lum−/−CD14−/− showed fewer bacterial phagosomes. We interpreted this as lumican deficiency interfering with the early stages of bacterial association to disrupt phagocytosis altogether (Fig. 3A). Overall, Alexa 488 E. coli association was reduced by 37% in lumican-deficient MΦs (Lum−/−, Lum−/−CD14−/−) but unaffected in the CD14−/− MΦs (Fig. 3B). We also tested phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa, using a GFP-expressing strain (PAO1) in in vitro assays and found its uptake to be reduced in the Lum−/− and Lum−/−CD14−/− MΦs as well (Fig. 3, C and D). On the other hand, uptake of Gram-positive S. aureus was not significantly impaired in the Lum−/−, CD14−/−, or Lum−/−CD14−/− compared with WT MΦs (data not shown). Future investigations will use macrophage-like cell lines, manipulated to express lumican, to further investigate regulation of intermediate steps in phagocytosis by lumican.

FIGURE 3.

Bacterial uptake delayed in Lum−/− MΦs. Peritoneal MΦs were incubated with bacteria for 20 min, fixed, and immunostained for Na/K-ATPase (red) as a plasma membrane marker. A, increased localization of Alexa 488 E. coli (green) on WT and CD14−/− compared with Lum−/− and Lum−/− CD14−/− MΦs. The lower panels show insets at higher magnification. Scale bars, 50 μm (upper panels). B, quantitative analyses of the images shown in A where the mean MFI/MΦ in WT is 100%. The data are the means of three plates ± S.D. *, p < 0.002 and representative of two experiments. C and D, GFP-PAO1 (green) association with the plasma membrane (red) was unaffected in WT and CD14−/− but reduced in Lum−/− and Lum−/−CD14−/− MΦs (means ± S.D. of three plates). *, p ≤ 0.004 of one experiment.

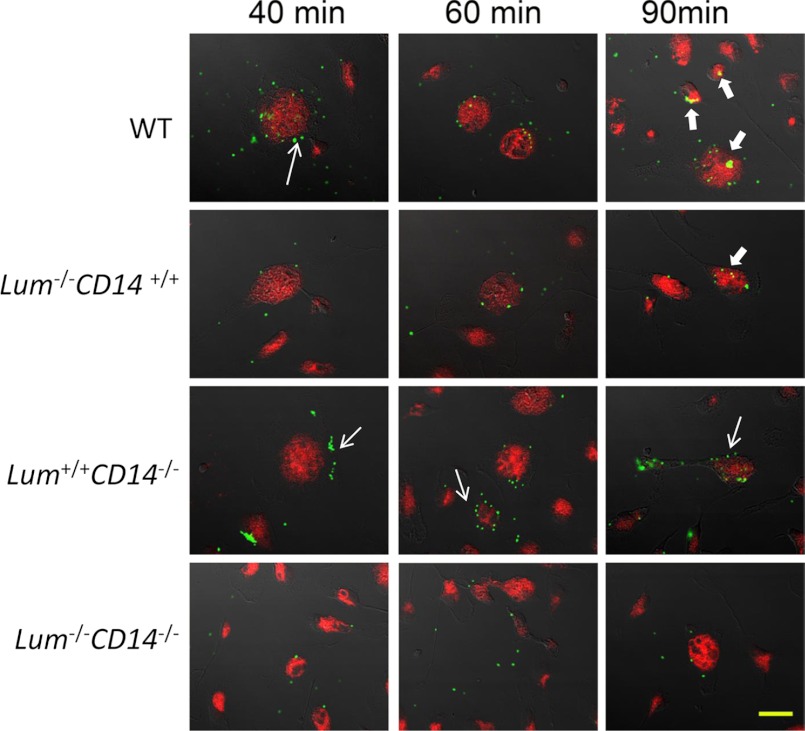

Appearance of Bacteria in Late Endosome/Lysosome Delayed by CD14 Deficiency

In the second stage, we asked whether the transfer of bacterial phagosomes to late endosome/lysosomes was affected by lumican deficiency. Peritoneal MΦs from WT, Lum−/−, CD14−/−, and Lum−/− CD14−/− double-null mice were incubated with bacteria for 40, 60, and 90 min, fixed, and then immunostained with a late endosome/lysosome marker LAMP-1 (Fig. 4). The WT MΦs showed multiple Alexa 488 E. coli bioparticles at the cell surface by 40 min (thin arrow), and by 90 min there were several co-localizations (yellow) with LAMP-1 (thick arrow). The number of early phagosomes appearing green, and those co-localizing with LAMP-1 and appearing yellow were counted for each microscopic field (Table 3). The Lum−/− MΦs showed few early bacterial phagosomes, confirming poor initial uptake in the absence of lumican; but of the few early phagosomes that were formed, by 90 min two of them co-localized with LAMP-1. In contrast, the Lum+/+CD14−/− MΦs showed as many early phagosomes (thin arrow), as the WT, but no co-localization with LAMP-1, and the double-null MΦs showed a lack of bacterial phagosomes and their co-localization with LAMP-1 (Table 3). We further confirmed poor fusion of bacterial phagosomes with late endosome/lysosome in CD14 deficiency by prestaining all four genotype of MΦs with LysoTracker® Red DND-99 and testing for uptake of Alexa 488 E. coli and passage to the lysosomal compartment by time lapse live cell confocal microscopy between 30 and 60 min of incubation (supplemental Fig. S4). For WT and Lum−/− MΦs, bacterial passage from the surface to acidic compartments occurred within 30–40 min of incubation, whereas the CD14-deficient MΦs (Lum+/+CD14−/− and Lum−/−CD14−/−) did not show phagosome acidification within these time frames. Thus, although bacterial uptake was significantly impeded in Lum−/− MΦs, phagosome acidification and fusion with late endosome/lysosome appeared to be unaffected.

FIGURE 4.

Delayed fusion of phagosomes with late endosome/lysosomes in CD14−/− MΦs. Peritoneal MΦs were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 E. coli BioParticles® conjugates for 40, 60, and 90 min. The cells were fixed and immunostained with anti-mouse CD107a (LAMP-1) Alexa Fluor® 647 antibody. Early phagosomes with bacteria appear green (narrow arrows). Overlaps (yellow) between E. coli (green) and LAMP-1 (red) were detected (thick arrows) in the Lum+/+ and Lum−/− MΦs but not in the CD14-deficient MΦs. Scale bar, 20 μm. Table 4 is a quantitative representation of this figure.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative estimate of phagosomes and late endosomes from Fig. 4

| Genotype | 40 min | 60 min | 90 min |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | |||

| Early phagosomea | 40 | 23 | 29 |

| Late endosomeb | 5 | 7 | 17 |

| Lum−/−CD14+/+ | |||

| Early phagosome | 2 | 4 | 10 |

| Late endosome | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lum+/+CD14−/− | |||

| Early phagosome | 42 | 26 | 31 |

| Late endosome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lum−/−CD14−/− | |||

| Early phagosome | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Late endosome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

a Early phagosomes appear green and were counted per field.

b Late endosomes appear yellow because of close proximity of GFP bacteria with LAMP-1 and were counted per field.

N-terminal Tyrosine of Lumican Involved in CD14 Interactions

We hypothesized that lumican acts as an intermediary between bacteria and CD14 to drive induction of cytokines and phagocytosis by CD14 (and TLR4). We considered four N-terminal tyrosine residues in lumican as functionally important for binding CD14 for the following reasons. These tyrosine residues of lumican have been shown by others to undergo post-translational sulfation (23). Tyrosine sulfation is a feature of other SLRPs, such as fibromodulin and osteoadherin, and suspected to support protein-protein interactions (23, 24). We developed two variants of rLum, rLumY20A and rLumY21A, where a tyrosine was replaced with an alanine in each (Fig. 5A), and by surface plasmon resonance determined their binding kinetics with CD14. The recombinant wild type protein rLum showed a dose- and time-dependent binding to CD14 immobilized on a CM5 sensorchip (Fig. 5B). As expected, anti-CD14 and nonspecific IgG, used as positive and negative control analytes, showed strong binding (KA = 8.26 × 109 m−1) and no measurable binding with CD14, respectively (Fig. 5, C and D). The CD14-rLumY20A interaction showed association kinetics that was comparable with rLum. However, dissociation of rLumY20A was rapid, such that the dissociation constant (KD) for CD14 and rLumY20A was 60-fold higher than that of CD14-rLum or CD14-rLumY21A (Fig. 5E and Table 4). Association and dissociation constants with CD14 were not adversely affected by the rLumY21A mutation (Fig. 5F and Table 4). To discount the loss of CD14 binding in rLumY20A as a purification-related artifact, we tested rLum and rLumY20A in collagen fibrillogenesis assays, often used as a test for biological activity for these ECM proteins (25). Collagen solutions form fibrils spontaneously in vitro, which can be tracked spectrophotometrically. The SLRP core proteins have been shown to bind collagen and inhibit fibrillogenesis. We found comparable inhibition of collagen fibrillogenesis by rLum and rLumY20A, suggesting retention of biological activity in rLumY20A, and the selective loss of its CD14 binding activity is most likely due to the tyrosine substitution (Fig. 5G).

FIGURE 5.

Surface plasmon resonance indicates weaker interactions of CD14 with rLumY20A. A, partial lumican protein sequence shown with signal peptide (gray) and the tyrosine residues (bold underlined) that were replaced with alanine residues in the mutant variants. B–F, CD14 was immobilized on a CM5 sensorchip, and analytes were injected for 1.5 min with dissociation time of 5 min at a rate of 25 μl/min. B, E, and F, wild type and mutant rLum in fluid phase were injected at six increasing concentrations (0.044–2.84 μm). C and D, anti-CD14 and control IgG analytes were used as positive and negative controls. Wild type and the mutant rLum show similar association (E, arrowhead), but dissociation of rLumY20A was dramatically rapid (E, arrow) compared with all other rLum types (Table 4). G, collagen fibrillogenesis was analyzed in the presence of wild type rLum and mutated rLumY20A. Both lumican forms demonstrated an inhibition of collagen fibrillogenesis, seen as an increase in the lag times required of initiation of fibrillogenesis as well as a decrease in the final absorbance. Both forms demonstrated comparable effects, indicating no difference in the biological activity. In this representative assay, the collagen I concentration was 100 μg/ml PBS, and rLum and rLumAY20A were present at a molar ratio of 1:6 (lum:collagen) at 34 °C. The assays were also done using collagen I concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/ml PBS at molar ratios of 1:6 and 1:1 (collagen:lum) and 34–35 °C. In all cases, the results were comparable with those presented.

TABLE 4.

Interaction between CD14 and analytes by SPR

| Anti-CD14 IgG | IgG | rLum | rLum-Y20A | rLum-Y21A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD | 1.21 × 10−10 m | Ua | 4.66 × 10−7 m | 2.86 × 10−5 m | 4.41 × 10−7 m |

| KA | 8.26 × 109 m−1 | Ua | 2.15 × 106 m−1 | 3.50 × 104 m−1 | 2.27 × 106 m−1 |

a U, undetectable.

Tyrosine 20 in Lumican Is Biologically Important for CD14 Functions

Because CD14 binding to rLumY20A was markedly reduced, we postulated that the tyrosine at position 20 is important for stable binding to CD14 and its functions in phagocytosis. Wild type rLum and rLumY21A could restore phagocytosis in Lum−/− MΦs, whereas the rLumY20A mutant improved phagocytosis by only 17.5% (Fig. 6A). To determine whether the CD14-binding region on lumican drives CD14 functions further in TLR4-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines, we tested rLum, rLumY20A, and rLumY21A for their abilities to restore LPS sensing and induction of TNF-α in Lum−/− MΦs. In the presence of rLum or mutated rLumY21A, the Lum−/− MΦs were able to respond to LPS and produce wild type levels of TNF-α, whereas the rLumY20A variant could not restore LPS response (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, rLumY20A interfered with normal LPS response in WT MΦs as well.

FIGURE 6.

rLumY20A unable to rescue phagocytosis or LPS-mediated induction of TNF-α in Lum−/− MΦs. MΦs were preincubated with 3 μg/ml of rLum, rLumY20A, or rLumY21A for 30 min. A, phagocytosis of pHrodoTM E. coli BioParticles® was measured after 1 h where mean MFI/MΦ in Wt is 100%. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.002. B, induction of TNF-α was measured by ELISA after 2 h of treatment with 10 ng/ml of LPS. rLumY20A is unable to restore TNF-α induction in Lum−/− MΦs (n = 3). *, p < 0.008. The data are representative of three (rLum) and two (rLum mutants) independent experiments.

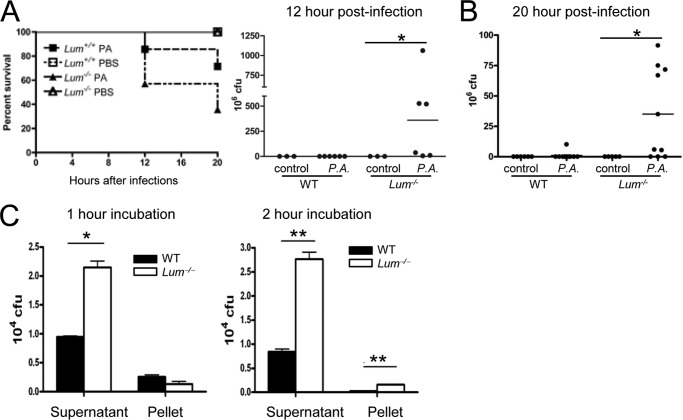

Pseudomonas Lung Infection Morbidity Increased in the Lum−/− Mice

To assess the relevance of lumican-driven phagocytosis in a disease setting, we tested the Lum−/− mice in a lung infection model using a virulent, cytotoxic strain of P. aeruginosa (ATCC 19660). By 12 h of infection, 42% of the Lum−/− mice died, as opposed to only 14% of the Lum+/+ mice. By 20 h, 64% of the Lum−/− infected mice had died (Fig. 7A). After 12 or 20 h of infection, bacterial clearance from the lungs was significantly impaired in the Lum−/− mice; the infected WT yielded few to no viable bacteria, whereas the Lum−/− lung homogenates yielded 106-109 cfu (Fig. 7B). In an in vitro bacterial killing assay, whereas both MΦ types reduced the total bacterial load markedly, the WT were two to three times more effective than Lum−/− MΦs (Fig. 7C). Histology of the 12-h infected Lum−/− lung tissues showed degeneration and necrosis/apoptosis of the bronchiolar epithelium, some atelectasis of alveoli, and mild neutrophil infiltrates (supplemental Fig. S5A). By 20 h of infection alveolar tissue damage in the Lum−/− mice was extensive (supplemental Fig. S5B). By flow cytometry, we detected increased F4/80+ cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage and increased Gr-1+ neutrophils by histology of lung tissues of the 20-h infected Lum−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). Our earlier study has shown that lumican promotes inflammatory cell migration, and in an LPS-corneal injury model, the Lum−/− corneas had shown delayed influx of neutrophils (26). However, in the lung infection model, by 20 h any delay in leukocyte migration in the infected Lum−/− lungs was clearly overcome, and levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the Lum−/− mouse bronchoalveolar lavage was WT-like (data not shown). However, increased mortality in the Lum−/− mice may be the result of a number of issues, reduced bacterial killing, poor epithelial healing, and reduced apoptotic clearing of inflammatory cells.

FIGURE 7.

Increased severity of P. aeruginosa (P.A.) lung infection in Lum−/− mice. The mice were infected with 108 cfu of P. aeruginosa ATCC19660. A, significantly increased mortality in infected Lum−/− mice (n = 9 PBS control and 14 infected mice per genotype). *, p = 0.011. B, viable bacterial yield in cfu from lung homogenates of ten infected and six control per genotype (20 h of infection) and six infected and three uninfected per genotype (12 h of infection) show significantly higher cfu from Lum−/− infected mice. *, p ≤ 0.005. C, in vitro phagocytosis by peritoneal MΦs. P. aeruginosa ATCC19660 (5 × 106 cfu) was incubated with MΦs (105); viable cfu determined in the supernatant and lysed MΦs after 1 and 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that association between bacteria and lumican and binding between lumican and CD14 promote phagocytosis by CD14. Lum−/− MΦs showed poor uptake of bacteria. Using three different confocal microscopy approaches, we showed that bacterial phagosome progression to lysosomes was delayed in Lum−/− MΦs. In P. aeruginosa-mediated lung infections, the Lum−/− mice showed poor bacterial clearance and a dramatic increase in mortality. P. aeruginosa is a common Gram-negative bacterium in cystic fibrosis patients, and a frequent nosocomial pathogen in ventilator-associated lung infections (27–31). Our study suggests a significant role for lumican in phagocytosis and resolution of bacterial lung infections. Although in vitro bacterial uptake and killing was reduced in Lum−/− MΦs, increased mortality of the infected Lum−/− mice may be due to a combination of events. Previous studies show that lumican is transiently expressed by injured epithelial cells, and epithelial wound healing in the cornea is delayed by lumican deficiency (26, 32). We have also shown that lumican promotes Fas-FasL-mediated apoptosis, with reduced apoptosis in injured Lum−/− mouse corneas (16). Thus, delayed epithelial healing and inefficient apoptotic removal of damaged cells and inflammatory infiltrates via Fas-FasL may also contribute to increased mortality and morbidity of Lum−/− mice in P. aeruginosa lung infections. Interestingly, an epithelial cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan, syndecan-1, regulates P. aeruginosa lung infections by facilitating resolution of neutrophilic inflammation (33). It remains to be seen whether transient expression of lumican by epithelial cells modulates syndecan-1 functions in lung infections.

Lumican is an ECM protein; to interact with the cell surface it requires specific cell surface proteins. Lumican was reported to bind MΦs in a divalent cation-dependent way that implicated integrins rather than scavenger receptors or CD14 (18). Our earlier studies demonstrated binding of lumican with CD18 and CD14 in immunoprecipitation and pulldown assays (15, 17). CD18 is the β2 integrin subunit of the complement component 3 receptor, known to regulate phagocytosis of complement-opsonized bacterial particles (34). However, we show that lumican-aided phagocytosis occurs primarily through CD14, and not CD18, as Lum−/− MΦs 1) phagocytose serum-opsonized Gram-negative bacteria normally and 2) are unable to phagocytose P. aeruginosa strain 808 (CD14 bias) efficiently. By surface plasmon resonance of lumican and its mutated variants, we further show that tyrosine 20 of the core protein is important in binding CD14. Other SLRPs, fibromodulin, and osteoadherin also have a tyrosine-rich N-terminal region that may be sulfated and involved in protein-protein interactions in the ECM, although no biological functions have been attributed to these sites yet (24, 35). CD14 has been shown to promote LPS-binding protein (LBP)-dependent phagocytosis that is also complement- and divalent cation-independent (36). CD14 is one of several proteins at the cell surface that regulate ligand recognition by TLR4 (7). Thus, in addition to interactions with CD14 and CD18, lumican may have other binding partners in this complex that impact its role in phagocytosis and innate immune response. No other SLRP members have been shown to regulate phagocytosis; however, we detected decorin on the surface of peritoneal macrophages also co-localizing with Alexa 488 E. coli, CD14, and CD18 (data not shown).

Functions of CD14 and TLR4 in phagocytosis are somewhat conflicted, and re-evaluation of the reported findings, after taking into consideration the opsonization status of the pathogens, may clarify some of this data. According to one study, CD14−/− MΦs showed no difference in the uptake of E. coli particles (37). Yet another reported CD14−/− mice to be hypo-responsive to E. coli with poor induction of proinflammatory cytokines and poor dissemination of bacteria introduced intraperitoneally (38). Using nonopsonized bacteria when we dissected the overall phagocytic process into bacterial uptake and phagosome acidification, we found clear distinctions in lumican and CD14 functions. The Lum−/− MΦs clearly had difficulties in bacterial uptake, whereas CD14−/− and the Lum−/−CD14−/− double null MΦs were dramatically delayed in forming late endosomes. The earlier contrasting report of no deficiency in phagocytosis by CD14−/− MΦs did not exclude serum, thus not accounting for CD14-independent phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria (37). Our current findings on CD14 in phagocytosis may provide new insights into the role of TLR4 in this process. TLR4 was generally thought to interact with target ligands in phagosomes and activate cytokine and chemokine induction, thus allowing efficient linking of inflammatory responses to microbial internalization (4). A later study reported that TLRs do more than jump start inflammatory cytokine production; TLR4 induced maturation of phagosomes containing bacteria in a MyD88-dependent manner (39). They further concluded that the inducible nature of phagosome maturation was autonomous, because LPS stimulation did not hasten phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, and only bacteria-containing phagosomes had the inducible quality. Taking our observation that phagosome maturation requires CD14, the direct contribution of TLR4 to phagocytosis may actually be due to membrane-anchored CD14 in the same phagosome. In further support of this concept, using an in vitro FRET-based technique, Yates and Russell (40) showed that stimulation of TLR4 or TLR2 had no effect on phagosome lysosome fusion.

An interesting point to consider is the source and form of lumican that regulates CD14 functions in macrophages. Lumican is present widely in many connective tissues (11, 19, 41, 42). We and others detected lumican by Northern blotting and in situ hybridization in mouse lungs (19, 21), and in vascular endothelial ECM (20) and HUVEC cultures (17) by immunoblotting. On the other hand, increased deposits of lumican and biglycan were reported in the lungs of asthmatic patients (43). In in vitro assays, we found MΦs from Lum−/− → WT BMC to show WT-like phagocytosis. Thus, as our earlier study suggested for neutrophils (17), MΦs acquire exogenous lumican from one or more of these ECM to enhance its phagocytic capabilities promote resolution of lung infection. Lumican exists in multiple post-translationally modified forms that may have distinctive functions in health and disease. In the collagen-rich stroma of the cornea, lumican exists in its keratan sulfate proteoglycan form, whereas in vascular ECM (20) and as we show in leukocyte exudates, it is a glycoprotein (17). The proteoglycan form of lumican may be less reactive with the cell surface; interactions of collagen fibrils with lumican in connective tissues may also protect the CD14-reactive N-terminal end of lumican from inappropriate amplification of innate immune responses. To this end, lumican and other SLRP fragments have been detected in degenerative joint diseases (44), whereas lumican levels have been variably associated with cancer and metastasis (45–49). There are only a few reports of other SLRP members displaying immune modulatory influences. Biglycan was reported to mimic danger signals in its soluble form and stimulate proinflammatory cytokines (50). Decorin and fibromodulin core proteins interact with the complement component C1q, and fibromodulin may promote the classical complement pathway (51). No other members of the 18 SLRP family constituents have been shown to have a definitive role in host defense against microbial infections.

In summary, we have elucidated a role for lumican in binding Gram-negative bacteria and driving CD14-mediated bacterial phagocytosis. An N-terminal tyrosine in lumican is required for binding CD14 and subsequent uptake of bacteria for ultimate pathogen clearance, such that lumican-deficient mice are grossly inadequate in fighting P. aeruginosa lung infection. Our study raises the possibility that tight regulations of cell-reactive lumican forms may be important to infections, repair, regeneration, and degenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Gibas and the Ross Confocal microscopy facility of the Hopkins Basic Research Digestive Disease Development Core Center for confocal microscopy-related assistance. We thank Seok Hyun Cho and Kristin Lohr for technical assistance with the lung infection model and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. We thank David E. Birk for designing the collagen fibrillogenesis assays.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant NEI EY11654 (to S. C).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- SLRP

- small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan

- MΦ

- macrophage

- rLum

- recombinant human lumican

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- BMC

- bone marrow cell chimera.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gresham H. D., Graham I. L., Griffin G. L., Hsieh J. C., Dong L. J., Chung A. E., Senior R. M. (1996) Domain-specific interactions between entactin and neutrophil integrins. G2 domain ligation of integrin alpha3beta1 and E domain ligation of the leukocyte response integrin signal for different responses. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30587–30594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frieser M., Hallmann R., Johansson S., Vestweber D., Goodman S. L., Sorokin L. (1996) Mouse polymorphonuclear granulocyte binding to extracellular matrix molecules involves β1 integrins. Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 3127–3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I., Nourshargh S. (2007) Getting to the site of inflammation. The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Underhill D. M., Gantner B. (2004) Integration of Toll-like receptor and phagocytic signaling for tailored immunity. Microbes Infect. 6, 1368–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Juan T. S., Kelley M. J., Johnson D. A., Busse L. A., Hailman E., Wright S. D., Lichenstein H. S. (1995) Soluble CD14 truncated at amino acid 152 binds lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and enables cellular response to LPS. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1382–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medzhitov R., Janeway C., Jr. (2000) Innate immune recognition. Mechanisms and pathways. Immunol. Rev. 173, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Triantafilou M., Triantafilou K. (2002) Lipopolysaccharide recognition. CD14, TLRs and the LPS-activation cluster. Trends Immunol. 23, 301–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeda K., Akira S. (2004) TLR signaling pathways. Semin. Immunol. 16, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McEwan P. A., Scott P. G., Bishop P. N., Bella J. (2006) Structural correlations in the family of small leucine-rich repeat proteins and proteoglycans. J. Struct. Biol. 155, 294–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vogel K. G., Paulsson M., Heinegard D. (1984) Specific inhibition of type I and type II collagen fibrillogenesis by the small proteoglycan of tendon. Biochem. J. 223, 587–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chakravarti S., Magnuson T., Lass J. H., Jepsen K. J., LaMantia C., Carroll H. (1998) Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly. Skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1277–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chakravarti S., Petroll W. M., Hassell J. R., Jester J. V., Lass J. H., Paul J., Birk D. E. (2000) Corneal opacity in lumican-null mice. Defects in collagen fibril structure and packing in the posterior stroma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3365–3373 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jepsen K. J., Wu F., Peragallo J. H., Paul J., Roberts L., Ezura Y., Oldberg A., Birk D. E., Chakravarti S. (2002) A syndrome of joint laxity and impaired tendon integrity in lumican- and fibromodulin-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35532–35540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ng A. C., Eisenberg J. M., Heath R. J., Huett A., Robinson C. M., Nau G. J., Xavier R. J. (2011) Human leucine-rich repeat proteins. A genome-wide bioinformatic categorization and functional analysis in innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, (Suppl. 1) 4631–4638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu F., Vij N., Roberts L., Lopez-Briones S., Joyce S., Chakravarti S. (2007) A novel role of the lumican core protein in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced innate immune response. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26409–26417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vij N., Roberts L., Joyce S., Chakravarti S. (2004) Lumican suppresses cell proliferation and aids Fas-Fas ligand mediated apoptosis. Implications in the cornea. Exp. Eye Res. 78, 957–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee S., Bowrin K., Hamad A. R., Chakravarti S. (2009) Extracellular matrix lumican deposited on the surface of neutrophils promotes migration by binding to β2 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23662–23669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Funderburgh J. L., Mitschler R. R., Funderburgh M. L., Roth M. R., Chapes S. K., Conrad G. W. (1997) Macrophage receptors for lumican. A corneal keratan sulfate proteoglycan. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38, 1159–1167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chakravarti S. (2002) Functions of lumican and fibromodulin. Lessons from knockout mice. Glycoconj. J. 19, 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Funderburgh J. L., Funderburgh M. L., Mann M. M., Conrad G. W. (1991) Arterial lumican. Properties of a corneal-type keratan sulfate proteoglycan from bovine aorta. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24773–24777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ying S., Shiraishi A., Kao C. W., Converse R. L., Funderburgh J. L., Swiergiel J., Roth M. R., Conrad G. W., Kao W. W. (1997) Characterization and expression of the mouse lumican gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30306–30313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heale J. P., Pollard A. J., Stokes R. W., Simpson D., Tsang A., Massing B., Speert D. P. (2001) Two distinct receptors mediate nonopsonic phagocytosis of different strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 183, 1214–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu Y., Hoffhines A. J., Moore K. L., Leary J. A. (2007) Determination of the sites of tyrosine O-sulfation in peptides and proteins. Nat. Methods 4, 583–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Onnerfjord P., Heathfield T. F., Heinegård D. (2004) Identification of tyrosine sulfation in extracellular leucine-rich repeat proteins using mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rada J. A., Cornuet P. K., Hassell J. R. (1993) Regulation of corneal collagen fibrillogenesis in vitro by corneal proteoglycan (lumican and decorin) core proteins. Exp. Eye Res. 56, 635–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vij N., Roberts L., Joyce S., Chakravarti S. (2005) Lumican regulates corneal inflammatory responses by modulating Fas-Fas ligand signaling. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zemanick E. T., Harris J. K., Conway S., Konstan M. W., Marshall B., Quittner A. L., Retsch-Bogart G., Saiman L., Accurso F. J. (2010) Measuring and improving respiratory outcomes in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Opportunities and challenges to therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 9, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cigana C., Curcurù L., Leone M. R., Ieranò T., Lorè N. I., Bianconi I., Silipo A., Cozzolino F., Lanzetta R., Molinaro A., Bernardini M. L., Bragonzi A. (2009) Pseudomonas aeruginosa exploits lipid A and muropeptides modification as a strategy to lower innate immunity during cystic fibrosis lung infection. PLoS One 4, e8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Safdar A., Shelburne S. A., Evans S. E., Dickey B. F. (2009) Inhaled therapeutics for prevention and treatment of pneumonia. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 8, 435–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lambiase A., Rossano F., Piazza O., Del Pezzo M., Catania M. R., Tufano R. (2009) Typing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients with VAP in an intensive care unit. New Microbiol. 32, 277–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pagani L., Colinon C., Migliavacca R., Labonia M., Docquier J. D., Nucleo E., Spalla M., Li Bergoli M., Rossolini G. M. (2005) Nosocomial outbreak caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing IMP-13 metallo-β-lactamase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 3824–3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saika S., Shiraishi A., Liu C. Y., Funderburgh J. L., Kao C. W., Converse R. L., Kao W. W. (2000) Role of lumican in the corneal epithelium during wound healing. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2607–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hayashida K., Parks W. C., Park P. W. (2009) Syndecan-1 shedding facilitates the resolution of neutrophilic inflammation by removing sequestered CXC chemokines. Blood 114, 3033–3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ricklin D., Hajishengallis G., Yang K., Lambris J. D. (2010) Complement. A key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 11, 785–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tillgren V., Onnerfjord P., Haglund L., Heinegård D. (2009) The tyrosine sulfate-rich domains of the LRR proteins fibromodulin and osteoadherin bind motifs of basic clusters in a variety of heparin-binding proteins, including bioactive factors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28543–28553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grunwald U., Fan X., Jack R. S., Workalemahu G., Kallies A., Stelter F., Schütt C. (1996) Monocytes can phagocytose Gram-negative bacteria by a CD14-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 157, 4119–4125 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moore K. J., Andersson L. P., Ingalls R. R., Monks B. G., Li R., Arnaout M. A., Golenbock D. T., Freeman M. W. (2000) Divergent response to LPS and bacteria in CD14-deficient murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 165, 4272–4280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haziot A., Ferrero E., Köntgen F., Hijiya N., Yamamoto S., Silver J., Stewart C. L., Goyert S. M. (1996) Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of Gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity 4, 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Blander J. M., Medzhitov R. (2004) Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from Toll-like receptors. Science 304, 1014–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yates R. M., Russell D. G. (2005) Phagosome maturation proceeds independently of stimulation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Immunity 23, 409–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roughley P. J., Lee E. R. (1994) Cartilage proteoglycans: structure and potential functions. Microsc. Res. Tech. 28, 385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dunlevy J. R., Beales M. P., Berryhill B. L., Cornuet P. K., Hassell J. R. (2000) Expression of the keratan sulfate proteoglycans lumican, keratocan and osteoglycin/mimecan during chick corneal development. Exp. Eye Res. 70, 349–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang J., Olivenstein R., Taha R., Hamid Q., Ludwig M. (1999) Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 160, 725–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sztrolovics R., Alini M., Mort J. S., Roughley P. J. (1999) Age-related changes in fibromodulin and lumican in human intervertebral discs. Spine 24, 1765–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brézillon S., Radwanska A., Zeltz C., Malkowski A., Ploton D., Bobichon H., Perreau C., Malicka-Blaszkiewicz M., Maquart F. X., Wegrowski Y. (2009) Lumican core protein inhibits melanoma cell migration via alterations of focal adhesion complexes. Cancer Lett. 283, 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leygue E., Snell L., Dotzlaw H., Troup S., Hiller-Hitchcock T., Murphy L. C., Roughley P. J., Watson P. H. (2000) Lumican and decorin are differentially expressed in human breast carcinoma. J. Pathol. 192, 313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu Y. P., Ishiwata T., Kawahara K., Watanabe M., Naito Z., Moriyama Y., Sugisaki Y., Asano G. (2002) Expression of lumican in human colorectal cancer cells. Pathol. Int. 52, 519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Naito Z., Ishiwata T., Kurban G., Teduka K., Kawamoto Y., Kawahara K., Sugisaki Y. (2002) Expression and accumulation of lumican protein in uterine cervical cancer cells at the periphery of cancer nests. Int. J. Oncol. 20, 943–948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Troup S., Njue C., Kliewer E. V., Parisien M., Roskelley C., Chakravarti S., Roughley P. J., Murphy L. C., Watson P. H. (2003) Reduced expression of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans, lumican, and decorin is associated with poor outcome in node-negative invasive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 207–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Merline R., Schaefer R. M., Schaefer L. (2009) The matricellular functions of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs). J. Cell Commun. Signal. 3, 323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sjöberg A. P., Manderson G. A., Mörgelin M., Day A. J., Heinegård D., Blom A. M. (2009) Short leucine-rich glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix display diverse patterns of complement interaction and activation. Mol. Immunol. 46, 830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]