Background: FAM20C is highly expressed in odontoblasts, ameloblasts, and cementoblasts.

Results: Fam20C knock-out mice displayed severe defects in dentin, enamel, and cementum, along with remarkable down-regulation of differentiation markers of odontoblasts and ameloblasts.

Conclusion: FAM20C is essential to the differentiation of tooth-formative cells and the formation of dentin, enamel, and cementum.

Significance: These data provide strong evidence that FAM20C plays a critical role in tooth formation.

Keywords: Calcification, Dentin, Gene Knockout, Mouse, Tooth Development, DMP4, FAM20C, Amelotin, Cementum, Enamel

Abstract

FAM20C is highly expressed in bone and tooth. Previously, we showed that Fam20C conditional knock-out (KO) mice manifest hypophosphatemic rickets, which highlights the crucial roles of this molecule in promoting bone formation and mediating phosphate homeostasis. In this study, we characterized the dentin, enamel, and cementum of Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C KO mice. The KO mice exhibited small malformed teeth, severe enamel defects, very thin dentin, less cementum than normal, and overall hypomineralization in the dental mineralized tissues. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry analyses revealed remarkable down-regulation of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) and dentin sialophosphoprotein in odontoblasts, along with a sharply reduced expression of ameloblastin and amelotin in ameloblasts. Collectively, these data indicate that FAM20C is essential to the differentiation and mineralization of dental tissues through the regulation of molecules critical to the differentiation of tooth-formative cells.

Introduction

Family with sequence similarity 20 is an evolutionarily conserved family comprising three members: FAM20A, FAM20B, and FAM20C (1). FAM20A was originally observed in the differential expression of hematopoietic cells undergoing myeloid differentiation (2). A mouse line expressing a viral transgene with the accidental deletion of a 58-kb fragment in chromosome 11E1, encompassing part of the Fam20A gene and its upstream region, showed growth disorder (3). Recently, it was found that FAM20A is highly expressed in ameloblasts, and its mutations are associated with human amelogenesis imperfecta and gingival hyperplasia syndrome (4). FAM20B is involved in cartilage matrix production and the timing of skeletal development in zebra fish (5), whereas FAM20C is highly expressed in the mineralized tissues (6) and has been reported as the causal gene for human lethal osteosclerotic bone dysplasia (Raine syndrome, OMIM 259775) (7). We recently found that Fam20C conditional knock-out mice exhibited hypophosphatemic rickets, indicating that this molecule is essential to the differentiation of osteogenic cells and may regulate phosphate homeostasis via the mediation of Fgf23 (8). Another recent report indicates that FAM20C is a kinase that is postulated to phosphorylate proteins secreted into the matrices of bone and tooth (9).

Mouse FAM20C, also known as “dentin matrix protein 4” (DMP4), contains 579 amino acid residues, including a putative 26-amino acid signal peptide at the N terminus. The C-terminal region of ∼350 amino acids (corresponding to residues 218–569 in the mouse FAM20C sequence) has been named the “conserved C-terminal domain” and contains a casein kinase domain highly conserved among different species (1, 9). Hao et al. (10) showed that the overexpression of mouse FAM20C accelerated odontoblast differentiation in vitro and that silencing this molecule by siRNA inhibited cell differentiation, implying that this protein may facilitate odontoblast differentiation.

Previously, we systematically analyzed the spatiotemporal expression of FAM20C in mouse teeth using in situ hybridization (ISH)2 and immunohistochemistry (IHC) approaches (6), which showed that this molecule is highly expressed in the odontoblasts, ameloblasts, and cementoblasts. The high expression levels of FAM20C in dental tissues strongly suggest that it may play important roles in the formation and mineralization of teeth.

In this study, we sought to define the biological functions of FAM20C during the development and mineralization of the tooth by analyzing Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C conditional knock-out mice. The Fam20C-deficient teeth displayed failure in the differentiation of the ameloblasts and odontoblasts, along with severe defects in enamel, dentin, and cementum. These findings support our previous hypothesis that FAM20C plays a critical role in odontogenesis (6).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Fam20C Conditional Knock-out Mice

The Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C conditional knock-out mice (Sox2-Cre-Fam20CΔ/Δ, KO mice) were generated as we previously described (8). Because the Cre recombinase driven by the Sox2 promoter is expressed at a very early stage of embryonic development (in epiblasts at embryonic day 6.5), nearly all tissues and cells in the KO mice express the recombinase (11). This means that Fam20C is inactivated in nearly all types of cells in the KO animals. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas A&M Health Science Center, Baylor College of Dentistry (Dallas, TX).

Tail PCR Genotyping

Genotyping of the Sox2-Cre-Fam20CΔ/Δ mice was determined by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from tails with primers as we described previously (8).

Generation of FAM20C Monoclonal Antibodies

We used the full-length mouse recombinant FAM20C (8) as the antigen to generate monoclonal antibodies against FAM20C. Briefly, five BALB/c mice were immunized with the recombinant FAM20C, and immunization boosting was given every 3 weeks for a total of four times (Creative Biolabs). Serum antibody titers were determined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The mouse with the highest titer for anti-FAM20C activity was given a final boosting and sacrificed for cell fusion. The positive clones were screened with the Omni-Hybridoma platform (Creative Biolabs). Three positive clones (clones 3, 5, and 6) with the IgG isotype were further screened using IHC and Western immunoblotting analyses. Clones 3 and 5, which were highly specific for FAM20C and showed high anti-FAM20C activities in both IHC and Western immunoblotting analyses, were expanded into the pristaned nude mice. The ascites from these mice were collected and purified using Protein G affinity chromatography (Harlan Bioproducts).

Plain X-ray Radiography and Microcomputed Tomography (Micro-CT)

The mandibles dissected from the WT and Fam20C KO mice were analyzed using plain x-ray radiography (Faxitron MX-20DC12 system, Faxitron Bioptics) and a micro-CT radiography Scanco micro-CT35 imaging system (Scanco Medical) with a medium resolution scan (7.0-μm slice increment), as reported previously (8, 12). The images were reconstructed with EVS Beam software using a global threshold of 240 Hounsfield units.

Backscattered Scanning Electron Microscopy

The mandibles were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. The specimens were then dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (70–100%) and embedded in methylmethacrylate without prior decalcification. The frontal section at the first lower molar level was mounted, carbon-coated, and examined with field emission scanning electron microscopy (Philips XL30, FEI Co.).

Preparation of Decalcified Sections and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

The mandibles dissected from the WT and Fam20C KO mice were fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated PBS solution at 4 °C and then decalcified in 0.1% diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated 15% EDTA (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 7 days. The tissues were processed for paraffin embedding, and 5-μm serial sections were prepared for H&E, IHC, and ISH staining.

Double Fluorochrome Labeling

Double fluorescence labeling was performed as described previously (8, 12). Briefly, calcein (5 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) was first administered into the 5-week-old mice by intraperitoneal injection, followed by injection of an Alizarin Red label (20 mg/kg intraperitoneally; Sigma-Aldrich) 7 days later. The mice were sacrificed 48 h after the injection of the second label, and the mandibles were embedded in methylmethacrylate, from which 10-μm sections were prepared. The unstained sections were viewed under epifluorescent illumination using a Nikon E800 microscope, interfaced with Osteomeasure histomorphometry software (version 4.1; Atlanta, GA). The mean distance between the two fluorescent labels was determined and divided by the number of days (seven) between the two labelings to calculate the mineral deposition rate, expressed as μm/day.

Immunohistochemistry

The IHC experiments were carried out using an ABC kit and a DAB kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The monoclonal anti-FAM20C antibodies (clone 3 or clone 5) were used at a dilution of 25 μg of IgG/ml. A polyclonal biglycan antibody (LF-159) was used as described previously (13) as well as antibodies against bone sialoprotein (BSP), dentin sialoprotein (DSP; the N-terminal fragment of DSPP), and DMP1 (14, 15). A polyclonal antibody against ameloblastin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was employed following the manufacturer's instructions. Methyl green was used for counterstaining.

In Situ Hybridization

The RNA probes for ameloblastin (AMBN), amelotin (AMTN), DMP1, DSPP, enamelin (ENAM), FAM20C, kallikrein-related peptidase 4 (KLK4), matrix metalloproteinase 20 (MMP20), and odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein (ODAM) were synthesized and labeled with digoxigenin using an RNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science) as described previously (6). The RNA probe for amelogenin (AMEL) was a gift from Dr. Fei Liu (Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine) (16). Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes were detected by an enzyme-linked immunoassay with a specific anti-digoxigenin-AP antibody conjugate (Roche Applied Science) and an improved substrate (Vector Laboratories), producing a red color for positive signals. Methyl green was used for the counterstaining.

Statistics

In the double fluorescence labeling experiments, we measured the mean distance between the two labeled zones in the first lower molars from six WT and KO littermates. Student's t test was employed to evaluate the difference of mineral deposition rate between the WT group and KO group. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Validation of Fam20C Ablation in the Teeth of Fam20C KO Mice

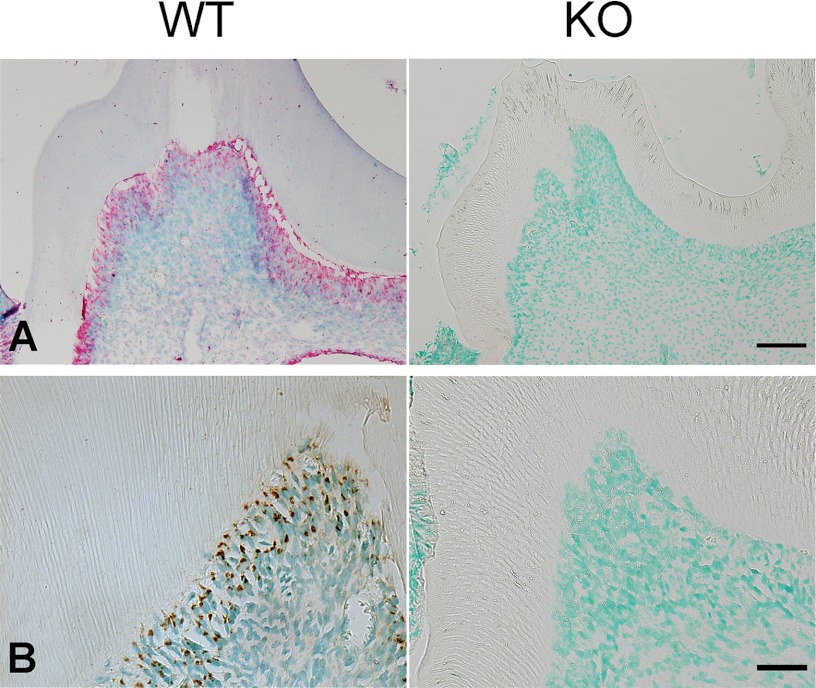

The lack of FAM20C mRNA in the Sox2-Cre-Fam20CΔ/Δ (KO) mice was shown by ISH analyses of the first lower molars (Fig. 1A). The loss of FAM20C protein was revealed by IHC analyses of the first lower molars using the monoclonal anti-FAM20C antibodies (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Validation of Fam20C ablation in the teeth of Fam20C KO mice. A, ISH of FAM20C was done on the first lower molars. The odontoblasts in the first lower molar of 3-week-old WT mice (left) had strong staining for FAM20C mRNA (red), in contrast to the lack of FAM20C mRNA signal in the KO mice (right). B, IHC of FAM20C on the first lower molars. The odontoblasts in the first lower molar of 3-week-old WT mice (left) showed positive staining for FAM20C protein (dark brown), whereas no positive signal for the protein was observed in the KO littermates (right). IHC was done using the monoclonal anti- FAM20C antibody (clone 5). Scale bars, 100 μm in A and 50 μm in B.

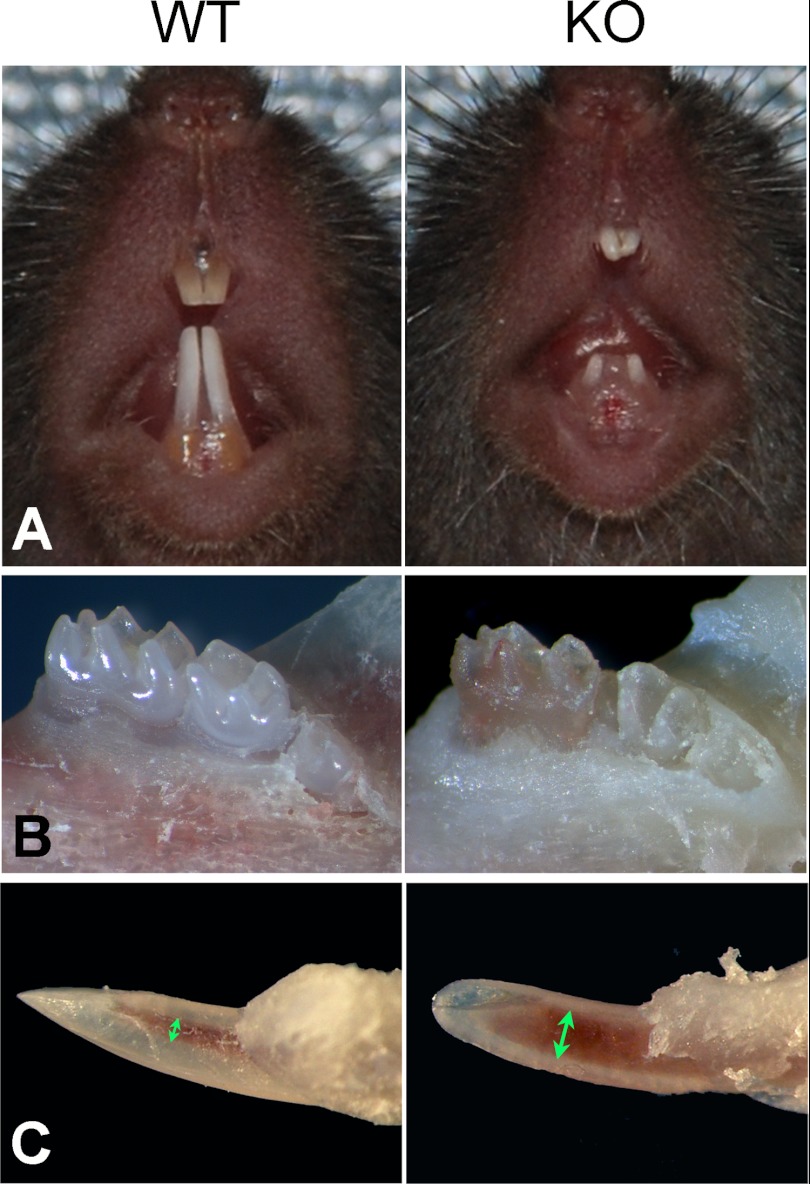

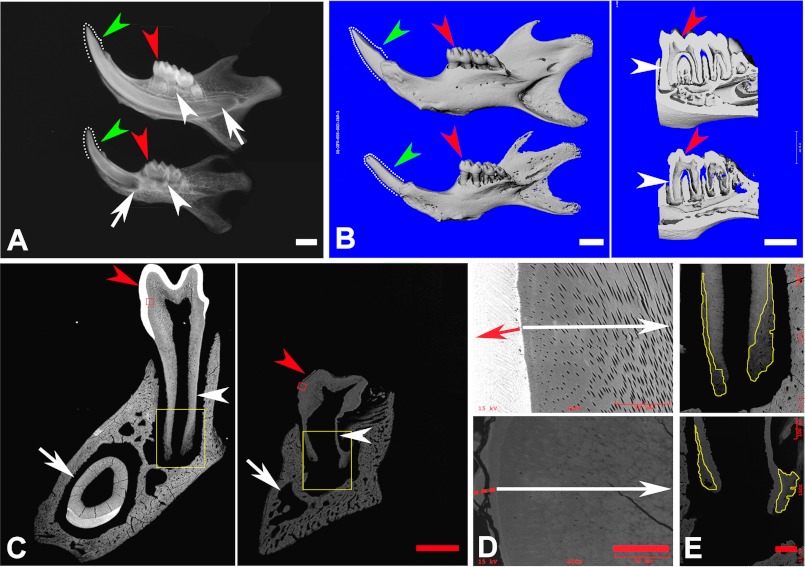

Fam20C KO Mice Exhibited Severe Tooth Defects

At the gross level, the incisors of the Fam20C KO mice were shorter (Fig. 2A) and had fewer mineralized tissues (Fig. 2, B and C) with enlarged pulp chambers (Fig. 2C) compared with their WT littermates. Both the molars and incisors of the KO mice exhibited malformed cusps. The pink color of the dental pulp in the Fam20C-deficient first molar became clearly visible (Fig. 2, B and C). Plain x-ray and micro-CT analyses showed that the KO mice had much shorter incisors, underdeveloped dental roots, loss of a clear boundary between enamel and dentin, thinner dentin, and enlarged pulp chambers, along with a generalized hypomineralization in the alveolar bones (Fig. 3, A and B). Backscatter scanning electron microscopy analyses indicated that the KO mice had smaller teeth and thinner dentin, with the root dentin being more severely affected (Fig. 3C), along with a lack of enamel structure (Fig. 3C), loss of dentinal tubules (Fig. 3D), less cellular cementum (Fig. 3E), and increased porosity in the alveolar bones (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 2.

Gross defects of teeth in the Fam20C KO mice. A, the incisors of 4-week-old Fam20C KO mice (right) were much shorter than those of their WT littermates (left). B, the molars of 3-week-old Fam20C KO mice (right) showed malformed cusps in comparison with the WT littermates (left). The pink color of the dental pulp in the Fam20C-deifient first molar became clearly visible. C, close-up views of lower incisors from the 3-week-old mice. The incisors of the KO mice (right) had larger pulp chambers (double arrows) and thinner hard tissues compared with the WT littermates (left).

FIGURE 3.

Plain x-ray, micro-CT and backscattered scanning electron microscopy analyses. A, plain x-ray analysis of the mandible from 3-week-old mice. In comparison with their WT littermates (top), the mandible of the KO mice (bottom) showed much shorter dental roots in both molars (white arrowheads) and incisors (arrows), thinner dentin without the enamel radiodensity on the surfaces of the molars (red arrowheads) and incisor ridges (green arrowheads, dotted lines), enlarged pulp chambers in both molars and incisors, and a generalized hypomineralization in the alveolar bones. B, micro-CT analysis of the mandibles from 6-week-old mice. Left, the mandible of KO mice (bottom) was smaller and more porous compared with that of the WT littermates (top). The smaller molars in the KO mice showed blunt and shorter cusps (red arrowheads). The malformed incisor in the KO mice lost wedge-shaped ridges (green arrowheads, dotted lines). Right, a sagittal scan section of molars in the KO mice (bottom) showed thinner dentin (red arrowheads) and an enlarged pulp chamber (note the extremely thin root dentin indicated by white arrowheads), in comparison with the WT littermates (top). C, backscattered scanning electron microscopy analyses on a frontal section at the first lower molar level in the mandible of 6-week-old mice. The KO mice (right) showed smaller and more porous mandibles and teeth compared with the WT littermates (left). The molar in the KO mice had thinner dentin and enlarged pulp chambers (note the extremely thin root dentin indicated by white arrowheads), with blunt cusps lacking enamel structure on the surfaces (red arrowheads). The incisors in the KO mice did not display a cross-section comparable with that of the WT due to the remarkably shorter root length (arrows). D, higher magnification view of the red boxed areas in C revealed a lack of dentinal tubules in the dentin of the KO mouse teeth (white arrow in the bottom image) compared with the well developed dentinal tubules in WT littermates (white arrow in the top image). The KO mouse teeth had very thin and hypomineralized enamel matrices on the dentin surface (red dashed line) compared with the well mineralized enamel in the WT mice (red arrow). E, higher magnification of the yellow boxed areas in C showed less cellular cementum (plotted with the yellow lines) in the KO mouse teeth (bottom) compared with the WT (top). Scale bars, 1 mm in A and B, 500 μm in C, 50 μm in D, and 100 μm in E.

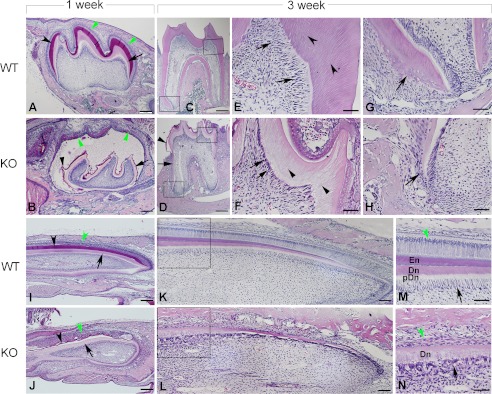

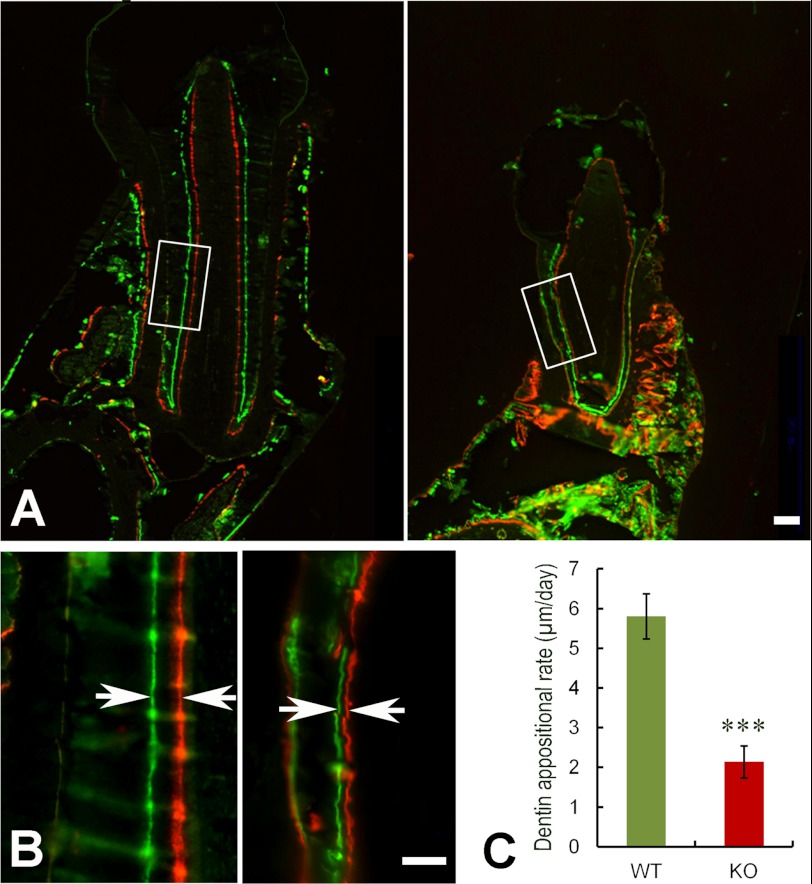

At postnatal 1 week, H&E staining of the first lower molars in the KO mice revealed that the teeth were smaller in size with thinner dentin (Fig. 4, A and B). The enamel matrices were very thin and loosely attached to the dentin. The depolarized and disorganized ameloblasts detached from the enamel matrix, and the enamel appeared as irregular masses (Fig. 4, A and B). At postnatal 3 weeks, the molars of the KO mice were smaller, the dentin was thinner (Fig. 4, C–F), and there was less cellular cementum (Fig. 4, G and H) compared with the WT. H&E staining of the lower incisors from 1-week-old KO mice showed porous dentin with very thin enamel matrices loosely attached to the dentin surfaces (Fig. 4, I and J). The disorganized ameloblasts secreted irregular masses of enamel matrix. The odontoblasts in the incisors of the 3-week-old KO mice were not polarized and formed thin and porous dentin, whereas the ameloblasts lost their columnar shape (Fig. 4, I–L). Double fluorochrome labeling analyses revealed a significantly reduced mineral deposition rate in the dentin of the KO mice (Fig. 5, A–C).

FIGURE 4.

H&E staining of the first lower molars and incisors. A and B, sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 1-week-old mice. The molar of KO mice (B) was smaller and had thinner dentin (arrow), with an extremely thin enamel matrix (dark arrowhead) loosely attached to the dentin, compared with the normal molar in A. The disorganized ameloblasts (green arrowheads) of the KO mice were detached from the enamel matrix and secreted irregular masses of enamel matrix-like material (red). Amorphous substance filled the gap between the ameloblasts and the enamel layer in the KO mice. C and D, sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. In comparison with the normal molar of WT in C, the molar of KO mice in D was smaller and had a larger pulp chamber, shorter roots, and thinner dentin (note the root dentin was more severely affected, as indicated by the black arrow), with an extremely thin and hypomineralized enamel matrix (arrowhead) on the crown surfaces. E and F, higher magnification of the upper right boxed areas in C and D showed that the Fam20C-deficient odontoblasts (arrows) in F lost their polarized columnar shape and formed defective dentin (arrowheads) composed of a porous structure instead of tubular dentin, in comparison with the normal odontoblasts and dentin of normal tooth in E. G and H, higher magnification of the lower left boxed areas in C and D showed that the tooth of KO mice in H had remarkably less cellular cementum (arrow) compared with the normal cellular cementum formed in the molar of WT mice (G). I and J, sagittal sections of lower incisors from 1-week-old mice. The incisor of KO mice in J showed porous dentin (arrow) and an extremely thin enamel matrix (dark arrowhead) loosely attached to the dentin. The disorganized ameloblasts (green arrowhead) of the Fam20C-deficient incisor secreted irregular masses of enamel matrix-like material (red) compared with the normal incisor of WT mice in I. K, sagittal sections of lower incisors from 3-week-old WT mice. L, sagittal sections of lower incisors from 3-week-old KO mice. M and N, higher magnification of the boxed areas in K and L revealed disorganized tissue layers of incisor in KO mice (N) compared with the normal incisor in M. The Fam20C-deficient odontoblasts (arrow) lost the columnar shape and formed porous dentin without a clear boundary between predentin and dentin. The disorganized ameloblasts (green arrowhead) were unable to form enamel in this region of the incisor in the KO mice, whereas in the same region of the WT mice, enamel was formed. En, enamel; Dn, dentin; pDn, predentin. Scale bars, 200 μm in A–D, I, and J; 100 μm in K and L; and 50 μm in -E-H, M, and N.

FIGURE 5.

Double fluorochrome labeling. A, frontal sections of the first lower molars from 6-week-old WT mice (left) and KO littermates (right). The first injection (calcein) produced a green label, whereas the second injection (Alizarin Red) 7 days later gave rise to a red label. The distance between the green and red labeling represents the mineral deposition of dentin in the period (7 days) between the two injections. B, higher magnification of the boxed areas in A showed that the dentin of the KO mice (right) had a narrower distance between the two labels (indicated by arrows in opposite directions) compared with the WT littermates (left). C, the quantitative measurements of the distance between the two injections revealed a significantly lower mineral deposition rate (expressed as μm/day) in the dentin of KO mice (n = 6) compared with that of the WT littermates (n = 6). ***, p < 0.0001. Scale bars, 100 μm in A and 50 μm in B.

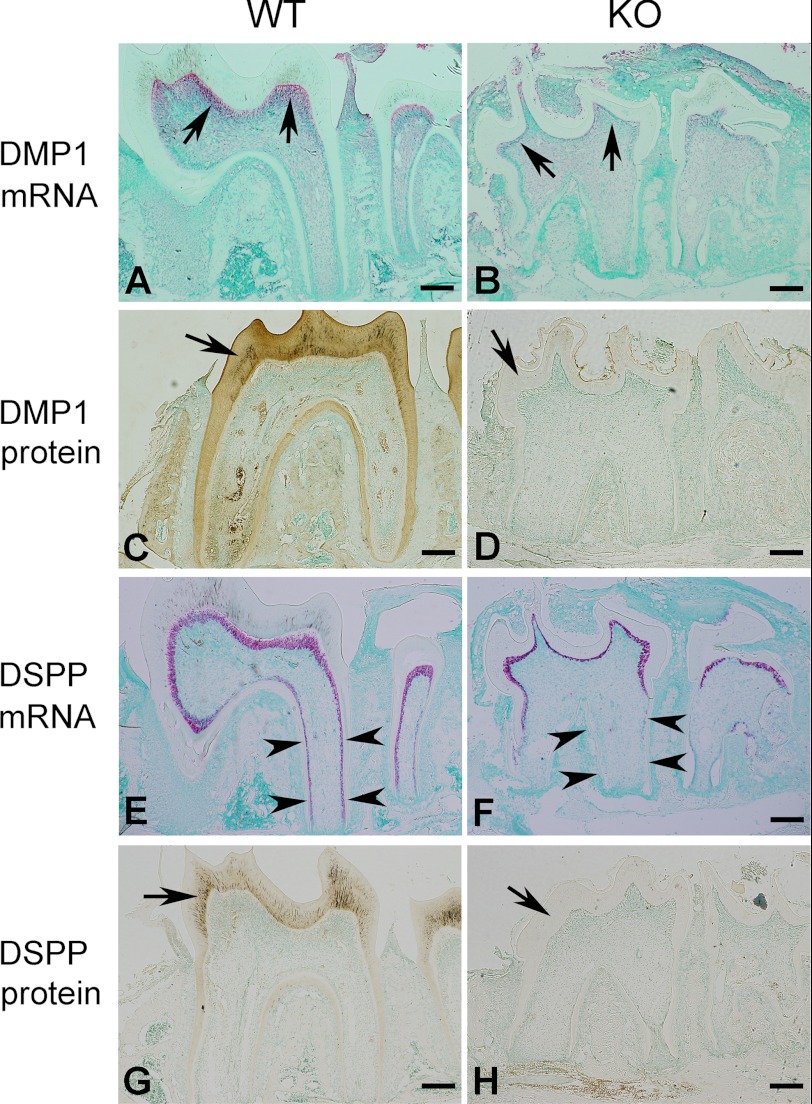

Altered Expression of Odontoblast Markers

ISH and IHC performed on the first lower molars of 3-week-old mice revealed a remarkable down-regulation of DMP1 in the Fam20C-deficient odontoblasts (Fig. 6, A–D). The mRNA level of DSPP in the coronal odontoblasts of the KO mice did not appear to be significantly lower than that in the WT mice, whereas a remarkably reduced level of DSPP mRNA was found in the Fam20C-deficient odontoblasts of the roots (Fig. 6, E and F). The expression pattern of DSPP was comparable with the dentin defect pattern in the Fam20C KO mice (i.e. the root dentin was more severely affected than the coronal dentin). DSP protein (the N-terminal fragment of DSPP) was almost undetectable in the Fam20C-deficient coronal and root odontoblasts of the KO mice (Fig. 6, G and H). It is worth noting that, unlike the C-terminal fragment of DSPP, the N-terminal fragment DSP has no or very little phosphate (17).

FIGURE 6.

DMP1 and DSPP are down-regulated in Fam20C-deficient odontoblasts. A and B, ISH of DMP1 on sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. The molar of WT mice (left) showed a strong DMP1 mRNA signal (red) in odontoblasts (arrows), whereas the molar of KO mice (right) had remarkably less DMP1 in the odontoblasts (arrows). C and D, IHC of DMP1 on sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. The molar of WT mice (left) showed a strong DMP1 protein signal (brown) in the odontoblasts and dentin matrix (arrow), whereas the molar of KO mice (right) had remarkably less DMP1 in the odontoblasts and dentin matrix (arrow). E and F, ISH of DSPP on sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. The molar of WT mice (left) showed a strong DSPP mRNA signal (red) in both the crown and root odontoblasts (arrowheads), whereas the DSPP expression in the molar of KO mice (right) was remarkably lower in the root odontoblasts (arrowheads) but not significantly affected in the crown odontoblasts of the KO mice. G and H, IHC of DSPP on sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. The molar of WT mice (left) showed a strong DSPP signal (brown) in odontoblasts and dentin matrix (arrow), whereas the molar of KO mice (right) had remarkably less DSPP in the odontoblasts and dentin matrix (arrow). Scale bars, 200 μm.

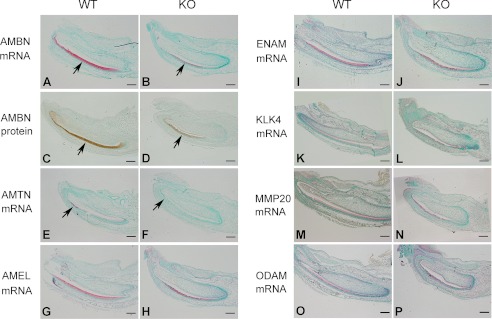

Altered Expression of Ameloblast Markers

To determine the molecular changes underlying the enamel defects in the KO mice, we examined several ameloblast differentiation markers in the teeth of newborn mice. ISH and IHC analyses revealed remarkable down-regulation of AMBN and AMTN in the Fam20C-deficient ameloblasts (Fig. 7, A–F), whereas the mRNA levels of AMEL, ENAM, KLK4, MMP20, and ODAM were not significantly altered in the KO mice (Fig. 7, G–P).

FIGURE 7.

Ameloblastin and amelotin are down regulated in Fam20C-deficient ameloblasts. A and B, ISH of AMBN on sagittal sections of the lower incisors from newborn mice. The incisor of WT mice (left) showed strong AMBN mRNA staining (red) in ameloblasts (arrow), whereas the incisor of KO mice (right) had remarkably less AMBN in the ameloblasts (arrow). C and D, IHC of ameloblastin protein revealed remarkably less AMBN (brown, arrow) in the ameloblasts of the incisor in the KO mice (right) compared with the WT mouse incisor (left). E and F, ISH of AMTN revealed remarkable down-regulation of AMTN in the mature ameloblasts (arrow) of the incisor in the KO mice (right) compared with the strong staining in the mature ameloblasts (red, arrow) of the WT mouse incisor (left). G–P, ISH of AMEL, ENAM, MMP20, KLK4, and ODAM showed no significant differences in the expression levels between KO (right) and WT mouse teeth (left). Scale bars, 200 μm.

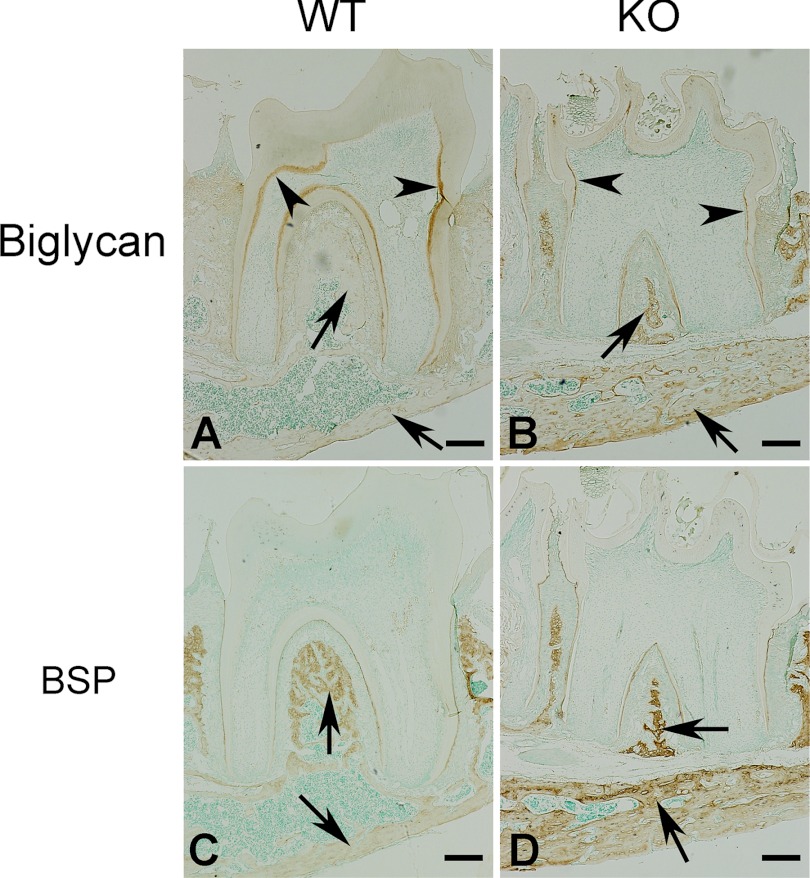

Biglycan and BSP Were Up-regulated in Fam20C KO Mandibles

Biglycan is a protein abundant in the unmineralized predentin and osteoid. IHC showed less staining in the predentin-dentin complex and more expression for biglycan in the alveolar bone of the Fam20C KO mice (Fig. 8, A and B). BSP, a member of the secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein (SCPP) family, was remarkably up-regulated in the alveolar bone (Fig. 8, C and D).

FIGURE 8.

Biglycan and BSP are up-regulated in Fam20C KO mice. A and B, IHC of biglycan on sagittal sections of the first lower molars from 3-week-old mice. The WT mouse molar in A showed stronger biglycan expression in predentin (brown, arrowheads), whereas the KO mice in B had remarkably up-regulated biglycan in the alveolar bone (arrows). C and D, IHC of BSP on the sections serial with those used in A and B. The KO mice in D had remarkably up-regulated BSP in the alveolar bone (arrows) compared with WT littermates in C. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Collectively, we conclude that the inactivation of Fam20C led to severe dental defects and remarkable down-regulation of certain odontoblast and ameloblast differentiation markers. These findings indicate that FAM20C is essential to the formation of dentin, enamel, and cementum.

DISCUSSION

FAM20C has been studied only to a limited extent. Previously, we systematically analyzed the spatiotemporal expression of FAM20C in mouse teeth and found that this molecule is highly expressed in odontoblasts, ameloblasts, and cementoblasts (6). A recent study revealed that FAM20C is a kinase that can phosphorylate the SXE motif of secretory proteins in the SCPP family in vitro (9). The SCPP proteins include SIBLINGs (small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins) (18), which comprise osteopontin, DMP1, BSP, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein, and DSPP. The SCPP family also includes the enamel matrix proteins: ODAM, AMTN, AMBN, and ENAM (19). In this study, we characterized the teeth of the Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C knock-out mice; the teeth of these mice showed severe defects in dentin, enamel, and cementum, which might be attributed to failures in the posttranslational phosphorylations of some secretory proteins in the SCPP family. Although we did not assess the phosphorylation levels of SCPP proteins in this investigation, we observed significantly reduced mRNA levels for Dmp1, Dspp, Ambn, and Amtn in the dental tissues and up-regulation of BSP in the alveolar bone of the Fam20C KO mice. The remarkable alterations at the transcriptional level for these molecules in vivo suggest that FAM20C may also regulate the expression of one or more of them through an undefined pathway(s) rather than simply exerting the posttranslational phosphorylation on these SCPP proteins.

Under physiological conditions, DMP1 is highly expressed in odontoblasts and osteoblasts/osteocytes. The importance of DMP1 for the formation and mineralization of dentin and bone has been demonstrated by in vitro mineralization studies (20) and in vivo genetic studies (21–23). We envision that FAM20C may regulate DMP1 in dentinogenesis and osteogenesis. This belief is based on the following observations: 1) the addition of recombinant FAM20C elevated the DMP1 mRNA levels in the MC3T3-E1 cells, whereas the shRNA knock-down of FAM20C reduced the DMP1 mRNA levels in three osteogenic cell lines (8); 2) the DMP1 mRNA levels in the bone of Fam20C KO mice were remarkably lower than those in the WT mice (8); 3) the skeletal and serum biochemistry changes of the Fam20C KO mice (8) resemble those observed in the Dmp1-deficient subjects (21–23); 4) the present study revealed that the DMP1 mRNA level in the odontoblasts of Fam20C KO mice was remarkably lower than that in the WT mice; and 5) the dentin and cementum defects of the Fam20C KO mice observed in this study resemble those of the Dmp1-deficient mice (21). These findings suggest that FAM20C may regulate DMP1, and the dentin and bone defects in the Fam20C KO mice may be completely or partially attributed to the remarkable down-regulation of DMP1 in these tissues.

In the Fam20C KO mice, the level of DSPP mRNA was not altered in the coronal odontoblasts but was significantly reduced in the root odontoblasts. We believe that this variation in the expression pattern of Dspp between coronal and root odontoblasts may be attributed to the differences in the controlling mechanisms governing root dentinogenesis and crown dentinogenesis. A number of studies have shown that the controlling mechanisms of root dentin formation differ from those that regulate the formation of coronal dentin (24–26).

DSPP has been shown to be critical for the formation and mineralization of dentin (27). Previous studies have shown that DMP1, in addition to its direct role in matrix mineralization, also enters the nucleus in the unphosphorylated form and regulates the transcriptional expression of Dspp (21, 28). The regulation of Dspp by DMP1 is further supported by our recent findings that the expression of the Dspp transgene driven by the 3.6-kb Col 1a1 promoter rescued the dentin defects in the Dmp1 knock-out mice.3 Thus, the reduced expression of DSPP in the root dentin of the Fam20C-deficient mice is probably due to the remarkable down-regulation of DMP1. Nevertheless, the regulation of DSPP expression during tooth formation may be very complicated. As the most abundant non-collagenous protein in the dentin matrix, DSPP, a critical molecule in dentin formation, may be a common downstream factor in multiple signaling pathways that are essential to dentinogenesis. The possible compensatory effects of signaling pathways other than the pathway in which DMP1 is involved may be responsible for the relatively normal level of DSPP mRNA in the coronal odontoblasts of Fam20C KO mice.

It is worth noting that the coronal odontoblasts in the Fam20C KO mice had a normal level of DSPP mRNA, whereas the DSP protein was absent in these cells. This observation indicates that the protein lacking proper posttranslational phosphorylation may be unstable and thus rapidly degraded after being synthesized.

Enamel is created by an appositional growth process in which ameloblasts continuously secrete organic extracellular matrix while slowly moving in the opposite direction until the desired thickness of the matrix is achieved. The amelogenesis process is divided into the presecretory stage, secretory stage, and maturation stage, with marker genes expressed at each phase. Over the past decade, mouse models engineered for the loss-of-function analyses of AMEL (29), AMBN (30, 31), ENAM (32), MMP20 (33), and KLK4 (34) have been reported. Among these engineered models, the enamel defects of Ambn KO and Enam KO mice (35) were very similar to those of the Fam20C KO mice. The AMBN level in the ameloblasts of the Fam20C KO mice was remarkably down-regulated, as shown by ISH and IHC analyses, whereas the expression levels of ENAM, AMEL, KLK4, MMP20, and ODAM were not significantly altered. These results suggest that FAM20C may regulate amelogenesis through the mediation of AMBN. Another molecule that was remarkably down-regulated in the Fam20C-deficient ameloblasts was AMTN, a component of the basal lamina covering the enamel surface, which helps ameloblasts adhere to the enamel surface via hemidesmosomes (36). The loss of AMTN in the Fam20C-deficient ameloblasts may have impaired the laminal junction between the ameloblasts and enamel surface, thus leading to the detachment of the ameloblasts from the initially secreted enamel matrix (Fig. 4, A and I). Collectively, the enamel defects in Fam20C KO mice might be a combined effect of AMBN and AMTN deficiency; the poorly differentiated ameloblasts secreted irregular masses of enamel matrix-like material and could not adhere on the matrix, thus leading to the loss of the enamel layer on the mature tooth surface.

In summary, we conclude that FAM20C is essential to the formation of dentin, enamel, and cementum. We envision that in addition to its potential roles in phosphorylating the SCPP proteins critical for dentin and enamel formation, FAM20C may facilitate the differentiation of odontoblasts and the mineralization of dentin through the regulation of DMP1, which subsequently regulates DSPP in dentinogenesis. In amelogenesis, FAM20C may facilitate the formation of enamel via the mediation of AMBN and AMTN.

As we previously reported, the inactivation of Fam20C in mice leads to a significant reduction of the phosphorus level in the serum (i.e. causing hypophosphatemia), in addition to the defects in the mineralized tissues. Because hypophosphatemia alone can also cause dentin defects, which was clearly evidenced in the transgenic mice overexpressing Fgf23 (37), the dentin defects in the Fam20C KO mice are likely to be a combined result of hypophosphatemia (systemic effects) and reduced levels of DMP1 and DSPP (local effects). The reciprocal interactions between the dental epithelium and dental mesenchyme play essential roles in tooth development. Because FAM20C is highly expressed in both odontoblasts and ameloblasts (6), it is unclear whether the dentin defects and enamel defects in the Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C KO mice are independent from each other or are associated with a failure in the epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in these mice with a global inactivation of Fam20C. Future studies using Wnt1-Cre mice to specifically inactivate Fam20C in odontoblasts and using K14-Cre mice to specifically knock out Fam20C in ameloblasts will provide clear answers to such questions. Because the Fam20C conditional knock-out mice mediated by Wnt1-Cre or K14-Cre may have a normal axial skeleton with no significant alterations in the serum levels of FGF23 and phosphate, these mice will also allow us to focus on the local effects of Fam20C inactivation on dentin or enamel. In addition, valuable information will be generated regarding to what extent the dentin or enamel defects of the Sox2-Cre-mediated Fam20C-deficient mice shown in this report can be attributed to hypophosphatemia (systemic) and what proportion of the defects is due to cell differentiation failure (local). Future studies are also warranted to isolate SCPP proteins from dentin and enamel to determine if the phosphorylation levels of these proteins are altered in the Fam20C-deficient mice.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeanne Santa Cruz for assistance with the editing of the manuscript and to Dr. Paul Dechow for support with the micro-CT analyses.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DE005092 (to C. Q.).

M. P. Gibson, Q. Zhu, Q. Liu, Y. Liu, X. Wang, J. Q. Feng, C. Qin, and Y. Lu, manuscript in preparation.

- ISH

- in situ hybridization

- DSPP

- dentin sialophosphoprotein

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- CT

- computed tomography

- BSP

- bone sialoprotein

- DSP

- dentin sialoprotein

- AMBN

- ameloblastin

- AMTN

- amelotin

- ENAM

- enamelin

- ODAM

- odontogenic ameloblast-associated protein

- SCPP

- secretory calcium binding phosphoprotein

- AMEL

- amelogenin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nalbant D., Youn H., Nalbant S. I., Sharma S., Cobos E., Beale E. G., Du Y., Williams S. C. (2005) FAM20. An evolutionarily conserved family of secreted proteins expressed in hematopoietic cells. BMC Genomics 6, 11–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Du Y., Campbell J. L., Nalbant D., Youn H., Bass A. C., Cobos E., Tsai S., Keller J. R., Williams S. C. (2002) Mapping gene expression patterns during myeloid differentiation using the EML hematopoietic progenitor cell line. Exp. Hematol. 30, 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. An C., Ide Y., Nagano-Fujii M., Kitazawa S., Shoji I., Hotta H. (2010) A transgenic mouse line with a 58-kb fragment deletion in chromosome 11E1 that encompasses part of the Fam20a gene and its upstream region shows growth disorder. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 55, E82–E92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Sullivan J., Bitu C. C., Daly S. B., Urquhart J. E., Barron M. J., Bhaskar S. S., Martelli-Júnior H., dos Santos Neto P. E., Mansilla M. A., Murray J. C., Coletta R. D., Black G. C., Dixon M. J. (2011) Whole-exome sequencing identifies FAM20A mutations as a cause of amelogenesis imperfecta and gingival hyperplasia syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 616–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eames B. F., Yan Y. L., Swartz M. E., Levic D. S., Knapik E. W., Postlethwait J. H., Kimmel C. B. (2011) Mutations in fam20b and xylt1 reveal that cartilage matrix controls timing of endochondral ossification by inhibiting chondrocyte maturation. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang X., Hao J., Xie Y., Sun Y., Hernandez B., Yamoah A. K., Prasad M., Zhu Q., Feng J. Q., Qin C. (2010) Expression of FAM20C in the osteogenesis and odontogenesis of mouse. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 58, 957–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simpson M. A., Hsu R., Keir L. S., Hao J., Sivapalan G., Ernst L. M., Zackai E. H., Al-Gazali L. I., Hulskamp G., Kingston H. M., Prescott T. E., Ion A., Patton M. A., Murday V., George A., Crosby A. H. (2007) Mutations in FAM20C are associated with lethal osteosclerotic bone dysplasia (Raine syndrome), highlighting a crucial molecule in bone development. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 906–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang X., Wang S., Li C., Gao T., Liu Y., Rangiani A., Sun Y., Hao J., George A., Lu Y., Groppe J., Yuan B., Feng J. Q., Qin C. (2012) Inactivation of a novel FGF23 regulator, FAM20C, leads to hypophosphatemic rickets in mice. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tagliabracci V. S., Engel J. L., Wen J., Wiley S. E., Worby C. A., Kinch L. N., Xiao J., Grishin N. V., Dixon J. E. (2012) Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science 336, 1150–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hao J., Narayanan K., Muni T., Ramachandran A., George A. (2007) Dentin matrix protein 4, a novel secretory calcium-binding protein that modulates odontoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15357–15365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayashi S., Lewis P., Pevny L., McMahon A. P. (2002) Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech. Dev. 119, S97–S101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sun Y., Prasad M., Gao T., Wang X., Zhu Q., D'Souza R., Feng J. Q., Qin C. (2010) Failure to process dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) into fragments leads to its loss of function in osteogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31713–31722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher L. W., Stubbs J. T., 3rd, Young M. F. (1995) Antisera and cDNA probes to human and certain animal model bone matrix noncollagenous proteins. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 266, 61–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang B., Sun Y., Maciejewska I., Qin D., Peng T., McIntyre B., Wygant J., Butler W. T., Qin C. (2008) Distribution of SIBLING proteins in the organic and inorganic phases of rat dentin and bone. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 116, 104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moses K. D., Butler W. T., Qin C. (2006) Immunohistochemical study of small integrin-binding ligand, N-linked glycoproteins in reactionary dentin of rat molars at different ages. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 114, 216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu F., Dangaria S., Andl T., Zhang Y., Wright A. C. (2010) β-Catenin initiates tooth neogenesis in adult rodent incisors. J. Dent. Res. 89, 909–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prasad M., Butler W. T., Qin C. (2010) Dentin sialophosphoprotein in biomineralization. Connect. Tissue Res. 51, 404–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kawasaki K., Weiss K. M. (2003) Mineralized tissue and vertebrate evolution. The secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein gene cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4060–4065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sire J. Y., Davit-Béal T., Delgado S., Gu X. (2007) The origin and evolution of enamel mineralization genes. Cells Tissues Organs 186, 25–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qin C., Brunn J. C., Cook R. G., Orkiszewski R. S., Malone J. P., Veis A., Butler W. T. (2003) Evidence for the proteolytic processing of dentin matrix protein 1. Identification and characterization of processed fragments and cleavage sites. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34700–34708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ye L., MacDougall M., Zhang S., Xie Y., Zhang J., Li Z., Lu Y., Mishina Y., Feng J. Q. (2004) Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19141–19148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ye L., Mishina Y., Chen D., Huang H., Dallas S. L., Dallas M. R., Sivakumar P., Kunieda T., Tsutsui T. W., Boskey A., Bonewald L. F., Feng J. Q. (2005) Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6197–6203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng J. Q., Ward L. M., Liu S., Lu Y., Xie Y., Yuan B., Yu X., Rauch F., Davis S. I., Zhang S., Rios H., Drezner M. K., Quarles L. D., Bonewald L. F., White K. E. (2006) Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat. Genet. 38, 1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zeichner-David M., Oishi K., Su Z., Zakartchenko V., Chen L. S., Arzate H., Bringas P., Jr. (2003) Role of Hertwig's epithelial root sheath cells in tooth root development. Dev. Dyn. 228, 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yokohama-Tamaki T., Ohshima H., Fujiwara N., Takada Y., Ichimori Y., Wakisaka S., Ohuchi H., Harada H. (2006) Cessation of Fgf10 signaling, resulting in a defective dental epithelial stem cell compartment, leads to the transition from crown to root formation. Development 133, 1359–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang X., Xu X., Bringas P., Jr., Hung Y. P., Chai Y. (2010) Smad4-Shh-Nfic signaling cascade-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal interaction is crucial in regulating tooth root development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 1167–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sreenath T., Thyagarajan T., Hall B., Longenecker G., D'Souza R., Hong S., Wright J. T., MacDougall M., Sauk J., Kulkarni A. B. (2003) Dentin sialophosphoprotein knockout mouse teeth display widened predentin zone and develop defective dentin mineralization similar to human dentinogenesis imperfecta type III. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24874–24880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Narayanan K., Gajjeraman S., Ramachandran A., Hao J., George A. (2006) Dentin matrix protein 1 regulates dentin sialophosphoprotein gene transcription during early odontoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19064–19071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gibson C. W., Yuan Z. A., Hall B., Longenecker G., Chen E., Thyagarajan T., Sreenath T., Wright J. T., Decker S., Piddington R., Harrison G., Kulkarni A. B. (2001) Amelogenin-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31871–31875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukumoto S., Kiba T., Hall B., Iehara N., Nakamura T., Longenecker G., Krebsbach P. H., Nanci A., Kulkarni A. B., Yamada Y. (2004) Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. J. Cell Biol. 167, 973–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wazen R. M., Moffatt P., Zalzal S. F., Yamada Y., Nanci A. (2009) A mouse model expressing a truncated form of ameloblastin exhibits dental and junctional epithelium defects. Matrix Biol. 28, 292–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu J. C., Hu Y., Smith C. E., McKee M. D., Wright J. T., Yamakoshi Y., Papagerakis P., Hunter G. K., Feng J. Q., Yamakoshi F., Simmer J. P. (2008) Enamel defects and ameloblast-specific expression in Enam knock-out/lacZ knock-in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10858–10871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caterina J. J., Skobe Z., Shi J., Ding Y., Simmer J. P., Birkedal-Hansen H., Bartlett J. D. (2002) Enamelysin (matrix metalloproteinase 20)-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49598–49604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simmer J. P., Hu Y., Lertlam R., Yamakoshi Y., Hu J. C. (2009) Hypomaturation enamel defects in Klk4 knockout/LacZ knockin mice. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19110–19121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith C. E., Hu Y., Richardson A. S., Bartlett J. D., Hu J. C., Simmer J. P. (2011) Relationships between protein and mineral during enamel development in normal and genetically altered mice. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 119, 125–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moffatt P., Smith C. E., St-Arnaud R., Simmons D., Wright J. T., Nanci A. (2006) Cloning of rat amelotin and localization of the protein to the basal lamina of maturation stage ameloblasts and junctional epithelium. Biochem. J. 399, 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen L., Liu H., Sun W., Bai X., Karaplis A. C., Goltzman D., Miao D. (2011) Fibroblast growth factor 23 overexpression impacts negatively on dentin mineralization and dentinogenesis in mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 38, 395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]